LINCOLN SCOTT AND BECKY ARNOLD

Lincoln Scott and Becky Arnold were active in Grand Union only for the first year or so. They both appear in photographs of the 1971 Walker Art Center performance, but only Scott continued to the January 1972 Oberlin residency. By the time of the LoGiudice Gallery series that May, he was no longer part of it. I do not have a vivid memory of either of them, so I am relying on other people’s descriptions.

LINCOLN SCOTT

Along with Brown and Lewis, Scott (born 1947) joined the group when it was mutating from CP-AD to Grand Union. He had performed in Brown’s Leaning Duets I (1970), in works by Deborah Hay, and in Trio A with Flags (1970). Deborah Hay remembers, “He always brought a modest, serious, and quiet presence to my dances.”1 Dilley remembers, “He was a gentle, fearless improviser and played along with us. And sometimes just watched.”2 Soon after arriving in New York, Scott chose to be known as “Dong.” People who knew him had various reactions to the new nickname.3

Theresa Dickinson, who was appearing as a guest artist, remembers dancing with Scott when Grand Union came to the San Francisco Art Institute in the summer of 1971. She described the rooftop of the Art Institute, with a high ledge above a deep drop. “Dong and I spent a very long time working on the problem of approaching each other along that ledge, then passing each other and continuing on.”4

At Oberlin in January 1972, Scott participated fully during Grand Union’s evening in Hall Auditorium. Judging from the video, he performed with commitment, energy, and sensitivity to his fellow dancers. He did not often initiate an action, but he joined in the group sweep of things; he had a shopping cart duet with Barbara, a strutting duet with David, and a howling duet with Yvonne.

Lincoln Scott was born in Louisiana in 1947 and moved to the Bay Area when he was young. He attended Berkeley High School, where he was recruited by dance teacher Betsy Frederick (then Janssen) to perform in the chorus of the musical The King and I. Frederick took Scott under her wing, cultivating his talent as a dancer. During his senior year, because of problems in his family, he lived in her garage. Frederick’s classes included technique and improvisation, and she brought her students to see Merce Cunningham and other companies when they came through the area.5

According to choreographer Wendy Rogers, who was a year behind Scott at Berkeley High, it was a large, progressive school with a proarts, pro-civil-rights agenda.6 Although the student population was racially diverse, in the community there was discriminatory housing and, in schools, academic tracking that favored white students. As happened (and still happens) all over the country, students would self-segregate in social situations. But, said Rogers, there was more mixing in dance and physical education. Further, “In the Bay Area dance world, however segregated and prejudiced we still were, there was a desire to change things and to create opportunities to do things together.”7 Rogers remembers at least one occasion when “the two Ruths”—Ruth Hatfield, teaching in Berkeley, and Ruth Beckford, the Dunham proponent who became a force for dance in the city of Oakland8—brought their students together: Hatfield’s mostly white students and Beckford’s mostly black students. This is all to say that Scott may have been socially comfortable in East Bay dance circles.

As always, dance teachers were happy when a boy expressed interest. Jenny Hunter (Groat), who had worked closely with Anna Halprin, probably offered him a scholarship to her school. She was known as a good teacher of both technique and improvisation. Rogers, who also studied with Hunter, remembers one whole session focused on initiating movement from the spine. Shortly after Scott came to Hunter, she invited him into her company, Dance West. They performed a work called The Effort at Fillmore Auditorium in 1966, which was advertised as “a subliminal archetype in theater, different every performance, a happenstance … you can walk around it.”9 Sounds like it could be Grand Union West!

Frederick found Scott likable and congenial. “He wasn’t what you’d call tremendously social, but he was nice to be around.”10 He smoked pot, but then so did many others at Berkeley High. When Scott left for New York, Frederick, who had known Paxton in high school in Arizona, gave him Steve’s contact information so he would have someone to stay with when he arrived. Scott did stay with Paxton in his place on the Bowery, then in an empty room on the upper floor of the same building, and again with Steve when he moved to Wooster Street.11

Scott formed a fleeting intimacy with Cynthia Hedstrom, who was dancing with Barbara Dilley in her group, the Natural History of the American Dancer. She and Scott were hanging out at 112 Greene and FOOD. She was new in New York and felt he had a kind of street smarts that she could learn from. As sculptor David Bradshaw recalled, Scott fit into the downtown dance scene, where “there was a Buddha quality to the whole crowd.”12 In the film documentary FOOD (1972), when Scott enters he is treated with respect and affection by his fellow artists.13

For a while Scott held a job at one of Mickey Ruskin’s restaurants or nightclubs, possibly Chinese Chance (also called One U, for One University Place, which was not as famous as Max’s Kansas City).14 As in Berkeley, however, he didn’t have his own home, and he would crash at his friends’ apartments.15

Hedstrom says she never saw any instance of racial discrimination when they were together in New York. But she suspected he may have had hidden insecurities about his place in that milieu. “He always had one foot in the door and one foot out of the door.”16 It couldn’t have been easy being one of the few African Americans in the largely white SoHo environment. Douglas Dunn remembers a time, probably when Grand Union had a gig in Cincinnati in 1970, when he and Steve and Lincoln were barred from a restaurant because of Lincoln’s presence.17

Scott was almost a decade younger than most of the other Grand Union members. Dance writer Sally Sommer, who saw many of the early performances, said, “I remember Dong as a presence and thinking he’s a very young, sweet guy. He was in the arena with these enfants terribles. For any young performer to come up to their performative level was very difficult.”18

In the flyer for the Oberlin residency, Scott had included the phrase “craft is apprentice” in his brief bio. It’s possible he thought of himself as apprentice to these master improvisers. He also wrote something quite poetic: “Bamboo player by the wind along California coast.” He did play a bamboo flute during the Oberlin performance, including making blowing sounds, as though he were the wind.

GU at 112 Greene Street, 1972. On left: Scott with mirror; in cluster: Dunn, Rainer, Paxton, Dilley. Photo: Babette Mangolte.

Steve, who often designed the posters, recounts an unfortunate situation at Oberlin: “A photo of the group was taken, and in a design choice I opted to print it in brown. The color was to make the color of the boots natural. Lincoln thought I chose it to emphasize his race. I think that was the beginning of him leaving, though it was, as most things were with him, not at all clear he was leaving or what he was doing.”19

Sometime after Oberlin (January 1972) and before LoGiudice (May 1972), Scott drifted away from Grand Union. David’s impression was that “Dong left after a while at his own choosing. To me he never seemed comfortable with the work we were doing but we never discussed it with him.”20

For long stretches of time, Scott stayed in Vermont, in the commune where Steve, Simone Forti, and Deborah Hay were living. According to Forti, it was like an extension of the SoHo and FOOD community.21 Scott participated in farm life, operating tractors, helping bale hay, and working in the organic garden.22 However, Forti said he was “unsure of himself” socially, and this may have had to do with his being “the only black person at the farm and for miles around.”23

Scott periodically returned to California after his stint with Grand Union. Nita Little, an early proponent of Contact Improvisation, met him in Berkeley in 1973 or 1974. She said he was living on the block on Divisadero Street where Anna Halprin’s Dancers’ Workshop studio was located. (He had at one point been attending weekly sessions with the Dancers’ Workshop.) As his girlfriend for a while, Little felt he was very present in a somatic way, especially his sense of touch. She also appreciated his politics because, as a Contact person, she questioned all hierarchy. (“Up is not necessarily good,” as she said, “and down is not necessarily bad.”) She felt that her conversations with Scott “forced me to have a perspective…. It was through him that I came to recognize how acculturated I was in the white culture. He woke me up to behaviors that were classist.” He was not overtly part of the black power movement, she said, but he “saw things in a political way.”24 Perhaps he felt more comfortable expressing his feelings about race and politics in California than in New York.

At some point he was hit by a car, badly hurt his leg, and became addicted to painkillers. From Steve: “He was also drinking a lot, so his life started to spiral downward. His last farm stay, a couple of years, was marked by paranoia and rages. He went to California upon the death of his father and dropped out of touch.”25

A Spokeo Internet search listed Lincoln Scott as having moved from Vermont to Berkeley in 2000, and there is no mention of him after 2017. After several attempts by his high school classmate Wendy Rogers to find him, there is no definitive update.

BECKY ARNOLD

Becky Arnold (born 1936) was in the cast of CP-AD as it developed and mutated into Grand Union. But she left New York in January 1972. Before I was able to locate her, I asked Yvonne to describe her: “Becky Arnold was an angel to work with, contentious, devoted, tireless—an accomplished technical dancer. She had no aspirations to do her own choreography or even contribute to mine as other than a worker bee, so when YR and Group was morphing into GU she made it clear the situation was not for her.”26

According to Pat Catterson, Arnold was strong and assertive, not as relaxed as the others in Grand Union. “She was … diligent, disciplined, wanting to get it right, and physically brave.”27

Arnold started lessons in gymnastics at the age of three in New Castle, Indiana. She would make dances for herself and her cousins to perform in her family’s garage. As an adult, she worked with Jack Cole and Michael Kidd in summer stock. Rainer saw her in Cunningham technique classes and asked her to come to a rehearsal. Becky’s response was, “I don’t think I can do your work.” But she eventually became a strong member of Rainer’s group. Before CP-AD, she danced in Rainer’s The Mind Is a Muscle (1966) and Rose Fractions (1969) and appeared (nude) with a big white balloon in Rainer’s short Trio Film (1968). She has vivid memories of Rose Fractions (1969): “We had a wall of us walking across the stage … with bags of kitty litter, and we opened them and strewn the litter as we walked across the stage.” Another memory: “There was a pile of books on the stage, and Yvonne said, ‘I want you to go and make love to the pile of books.’ So I did.”28

The Pratt performance of 1969 was a precursor to CP-AD in that it was the first time Yvonne included a dancer learning something in the performance. That person was Becky, and that material was Trio A. She must’ve done a good job because Catherine Kerr, the Cunningham-dancer-to-be who was in the audience, came away with a strong impression of Becky as a lively performer.29

Becky felt very much part of the making of CP-AD—the testing out of ideas, kicking the pillows around, moving boxes, using leverage to stand up with the group supporting her, choosing when to do “Chair Pillow”—even though she was seven months pregnant when they premiered it at the Whitney. For the group hoist, which had been worked out at ADF the summer before, she had to be replaced by Yvonne. Another concession to her pregnancy was that Deborah Hollingworth, who had designed the “adjuncts” for the University of Missouri at Kansas City performance, made a papier mâché hemisphere to cover her belly at the Whitney.

But when it came time to improvise, Becky was not comfortable. She had felt safe complying with Yvonne’s clear commands, but this was a new, open-ended situation. She found this new phase “really upsetting because I wanted to just be told what to do and to know what I was going to do. All of a sudden, I didn’t know what was going to happen.”30 The part she liked about Grand Union was the physicality: “One night Steve came over and plopped his body on top of me, and I responded back.”31

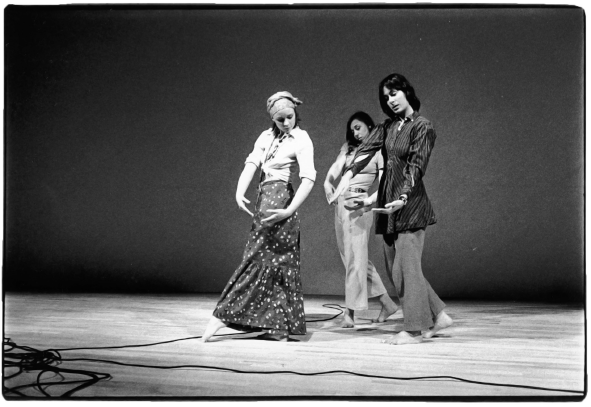

GU at Walker Art Center, lec-dem, 1971. From left: Dilley, Becky Arnold, Rainer. Photo: Tom Berthiaume, courtesy Walker Art Center.

When her husband got a new job in Andover, Massachusetts, she moved away from the city. Well after she had left Grand Union, in 1977, Arnold produced her own concert at NYU, performing works by Rainer, Catterson, Peter Saul, and Dan Wagoner. Since that time, she has studied tango in Buenos Aires and competed in the ballroom scene. She lives in Phoenix, where she still dances at milongas twice a week.

PEOPLE IMPROVISATION

In a way, this book is an expansion of the review I wrote about Grand Union at La MaMa in 1976, which appeared in my last book, Through the Eyes of a Dancer: Selected Writings (Wesleyan University Press, 2013). I titled my review, which originally appeared in SoHo Weekly News, May 6, 1976, “People Improvisation.” Trisha had left the group a few months earlier, and Steve Paxton was probably busy with Contact Improvisation. In their absence, it was decided that Valda Setterfield would appear as a guest artist. Two caveats about this article: first, I have no idea what category of Japanese swordsmen I was referring to or what I meant by traditional Eastern opera, and second, when it came to describing Barbara Dilley, I realize now that I was seeing only a narrow band of this highly dimensional dance artist.

Ancient Japanese swordsmen would customarily train for many, many years to attain one simple goal: to be ready to accept, and counter, a blow from any direction at any time. The swordsman’s decision was not permitted to rely on any previously successful strategy. Rather, he was to take into account all the forces of the present moment and choose the one action perfect for that unique moment.

The difference between this theory and the theory that the Grand Union goes by is that for the latter, there is more than one appropriate action in a given situation. It is the choice, among the range of possible alternatives, that the performers, and we, are interested in. When X does this, what will Y do? Or, when Z does this, what will Z then do? Each initiated action opens up a new realm of possible reactions. Each reaction opens up … etc. Endings are beginnings. The performers create a constantly shifting matrix of joinings and separations, rises and falls, quickenings and trailings off, revelations and suppressions.

The way the Grand Union accomplishes all this is by having near-legendary rapport as a group, and by each member having a strong identity of his/her own. Like the loyal audiences of traditional Eastern opera, we have come to know each character well; they are varying degrees of real/unreal for us; and we each have our favorites. A brief run-down is in order:

Barbara Dilley is small and soft, wears comfortable clothes that let her comfortable body extend and curl and twine. She is patient and well grounded in manner and motion. She usually avoids verbal content and when pressed, responds somewhat too earnestly. (“A leader is someone who has wisdom,” she informs David Gordon.)

Douglas Dunn is lean and angular, with a determined look on his face. The black clothes and hat he wore on Sunday night made him look preacher-like, and he played into that by striking stark poses. The intention in his dancing is very evident, and he likes to channel this clarity into weight studies—lifting, catching, yielding to, testing another’s weight.

David Gordon has an uncommon gift for monologue. He tops his own brilliant witticisms with more brilliant ones. He banters, puns, weaves tales, plays the prophet, plays the victim.

Nancy Lewis is tall and goofy and, although she has been compared to Carol Burnett, I see more of Holly Woodlawn [one of Andy Warhol’s gender-nonconforming “superstars”] in her. It is fun to watch her mercurial changes between chic, sulky, and disarmingly sensual. She is a parody of herself, letting us know by a darting glance or a droop of the shoulders that she doesn’t believe in this stuff 100 percent. This creates a contrast to her dancing, which is full and swoopy and emanates from an inner center.

Valda Setterfield, who danced with Merce Cunningham for a long time, is long and sleek; she looks the height of elegance in whatever eccentric outfit she drums up. Her dancing is distinctive for its effortlessly clean lines and the matter-of-fact way she drops into and out of movements.

These dancers are such colorful characters that we are drawn to their performances again and again, as though to a new installment of a soap opera. We follow their triumphs, disappointments, dares, and frustrations almost too keenly to be bearable. We feel the challenge of spontaneity, the chaotic assortment of possibilities as we do in our own lives. We know that there is no plan. We witness the trust that allows them to bring their personal doubts into play. On one occasion, Lewis stood at the back of the room with a blanket over her head for a long time and finally, during a pause, asked anyone who would listen, “Am I doing anything important?”

However, the group sometimes relies too heavily on bits, or types of bits, that have gone over well in the past. Each member is, at different times, limited by the very illustriousness that makes him or her magnetic.

But the Grand Union is still the best improvisation group around, and there are still those moments that stun you by being so utterly in the present. On Sunday, Gordon had got himself standing on a chair, slowly revolving as he told a story of himself as a bed-wetting adolescent who joined the circus. The narrative seemed unconnected to anything else going on until he eventually directed it to the moment at hand: “I love having hundreds of people watch me turn around on top of this chair…. This is the best moment of my life.” But moment gives way to moment, and exhilaration gives way to misery: “How long will you let me go on like this…. You’re making me turn around on this chair…. This is the worst moment of my life!”

Yvonne Rainer, who was a founder and strong influence on the group, has written that “one must take a chance on the fitness of one’s own instincts.”1 (She’d make a good Japanese swordsman.)

Part of this means an instinct for play, which might loosely be defined as non-goal-oriented exploration. Most of the Grand Union members have children, and I see evidence of that influence in their ability to play. They even use the word “pretend.” Gordon: “We were pretending to be chickens mating and I resent your calling it dancing.” (“Let’s pretend”—that magical gateway to endless delights for children, but a phrase that has been dropped from the adult vocabulary.) This time they even looked like children—children playing dress-up in the morning with their pajamas still on. They all wore combinations of plain and fancy.

“Instincts” can also mean learned abilities. The instinct that improvising requires includes knowing when to let go of an action and when to forge ahead, when to claim the focus and when to give it up, and what proportion of personal wishes and fears to lay bare.

Needless to say, these are the same issues we face in everyday living. Perhaps that’s why I leave a Grand Union performance not with a declaration of good or bad, but with an emotional fullness, similar to the effect of a highly charged event in my own life.

After one of the performances, a woman told Barbara Dilley, “I’ve seen dance improvisation before, and I’ve seen theater improvisation before, but this is the first time I’ve seen people improvisation.”