Grand Union gave more than fifty performances during its six years, yet only twelve were videotaped (that I know of). There are two reasons for this: first, though it’s hard to picture in today’s overexposed world, video was not routinely used back then; most video cameras were large and expensive, and not many dancers owned one. Second, Grand Union dancers were not interested in documenting their work. As Nancy Lewis reminded me, they were “adamant” about avoiding any record of their improvised performances.1 The idea was to be in the moment and not worry about past or future. However, video recordings do exist from Oberlin, LoGuidice Gallery, Walker Art Center, University of Iowa, La MaMa, Seibu in Tokyo, and the University of Montana at Missoula. (There is also a homemade film of the informal performance in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, and a few seconds of confusing footage from the rooftop of the San Francisco Art Institute, both in 1971.) Some were shot by the presenting organization and others by individuals. Not all have been well maintained and digitized.

Video is a far cry from live dancing. The two-dimensional format flattens the dancing, and the camera’s framing doesn’t tell the whole story. Therefore, I had decided not to attempt to “translate” these artifacts to the page. I was planning to rely on interviews, photographs, and people’s memories (my own included). And then … I received a message from the dead.

Let me explain. I came across a book review of Margaret Hupp Ramsay’s The Grand Union (1970–1976): An Improvisational Performance Group. This book, mentioned in the introduction, has been helpful to me, especially for its listings of performance dates and articles. The review, written by Marianne Goldberg, appeared in Dance Research Journal in 1994. (It happens that both Ramsay and Goldberg earned their PhDs from NYU’s Department of Performance Studies. Remarkably, they were both in a course that I cotaught at NYU with, and on, Trisha Brown in 1982.)

In her review, Goldberg, who died in 2015, appreciated Ramsay’s efforts but wrote: “What is most absent [in Ramsay’s book] is sustained description or analysis of performance material…. Ramsay does not tell much about how one improvised moment follows others, or about how the shape of an evening or series of evenings progressed, backtracked, cross-referenced, or stalled. Instead she gives glimpses of moments taken from the six-year period…. My response to this absence is longing for knowledge about improvisational content, in as much depth as possible.”2

I fixated on the word longing. I realized that I too had this longing, and that the only way to provide the “improvisational content in as much depth as possible” was indeed to “translate” the archival videos to the page. To me, this meant going past the intriguing or hilarious glimpses that people—both performers and audience—remember, and witnessing the ebb and flow of the collectively created waves of activity.

One could watch Grand Union (either live or on video) through any one of several filters. You could concentrate on the performers’ individual movement explorations, on how their dancing drew them into interactions with each other, or on how those interactions escalated into psychological dramas. You could watch how a recurring motif found its way into a different situation, accumulating new shades of meanings. You could watch them create or lose momentum. You could watch them knit together scattered actions and watch those strands come apart. You could watch them join a collective fantasy as it gathers steam. Or, you could shift between all these modes, because that is what Grand Union did.

Considering that they were improvising every minute, the flashes of cohesiveness were quite astonishing. There was no set choreography or even a bare-bones structure. And yet they planted seeds that sprouted later in the program or gave hints of narrative to chew on—a ladder here, a length of cloth there. They seemed to have a sixth sense, a subliminal ability to use their peripheral vision—or perhaps something like echolocation that only certain species have—to know where the others were in space.

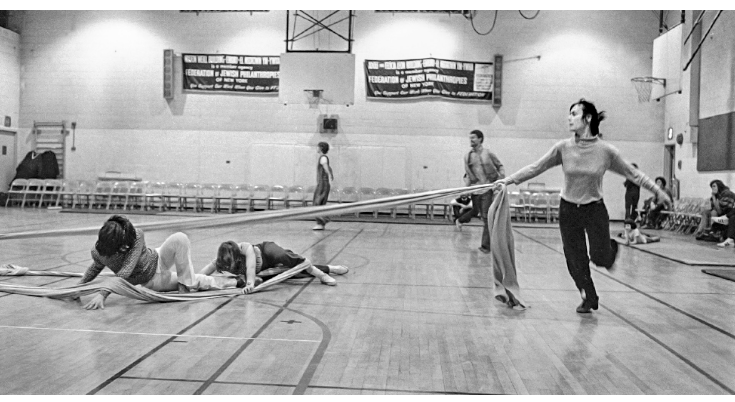

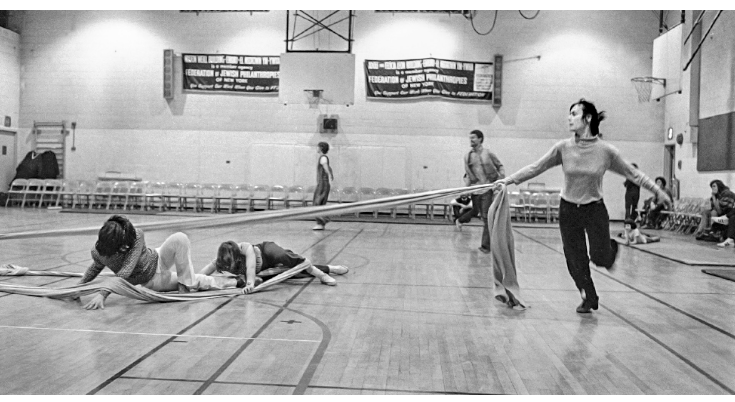

GU performance at NYC Dance Marathon, 14th Street Y, 1971. From left: Gordon, Arnold, Lewis, Scott, Rainer. Photo: James Klosty.

They each had moments of uncertainty, of drifting or spacing out. But it was remarkable how rare those moments were. They were more often in the zone of “I am doing this now. I am not waiting to find out if it’s any good or if I could’ve made a better choice. I am not judging myself. I am just throwing myself into it.”

Grand Union dancers never laughed at each other’s jokes or showed surprise in any way. They were inside the world they created together, ready for anything. There seemed to be no limit to their trust in each other. Their weaving together of intention and happenstance, as inextricable as warp and woof, often yielded moments that were offhandedly, startlingly beautiful.

What I’ve tried to do in these descriptions that I am calling “narrative unfoldings” is to give a sense of the flow—of how one thing led to, coexisted with, or interrupted another. Physical and psychological interactions unfolded with the illusion of inevitability. Whether subliminally engaged in narrative or not, the Grand Union dancers allowed each other to complete the story or the picture. One could say they each had an animal’s instinct for knowing they were part of a larger ecosystem.

I’ve chosen five of the videos to “translate,” to give some sense of the ebb and flow: the first, third, and fourth performances from LoGiudice Gallery in 1972, the one at the University of Iowa in 1974, and the lobby event from Walker Art Center in 1975. Most of the performances were about two hours long, shot by a single camera. Some of the action took place outside the camera’s frame, and I’ve edited out some of the detail that was visible (or else this book would be thousands of pages long). This means that I have shaped the unfoldings according to my own sense of cause and effect—or sometimes the logic of non sequiturs. Another person would notice different things and break the sessions up in a different ways. However, I’ve immersed myself in these videos and have strong memories of each dancer in the group. So, consider these “narrative unfoldings” one person’s annotated version.

I have used the present tense in order to bring some immediacy to these renderings. In a way, these actions do exist in the present—digitally.