FIRST LOGIUDICE VIDEO, MAY 1972

In the early days of Grand Union, when Yvonne Rainer was still a member, the performances sometimes took on a highly emotional quality. No longer the leader, Rainer had lost some of the sense of purpose that drove her to make CP-AD. In Grand Union, she allowed herself to become unknowing and vulnerable. At the same time, others were feeling their oats. Trisha found she could exert control over her fellow performers; David found he could use words to tell stories, to entertain, or to reverse the course of a scene; Nancy could organically develop a complete solo, building it with intricacy and force; Barbara was not afraid to tread the line between athletic and sexual; Steve could slow things down, exerting a gravitational pull. Douglas (who was not present in this first video) could explore movement with great intention no matter what the others were doing.

Following is a description of the first reel of the four 1972 performances at LoGiudice Gallery in SoHo (downstairs from The Kitchen), which was videotaped under the direction of Carlota Schoolman at the suggestion of Trisha Brown. For a while the narrative seemed to gather around a toy gun: who had it, who refused it, who pulled the trigger. It reminded me of how, while watching José Limón’s The Moor’s Pavane, if you just followed the white handkerchief you could get the whole story that way. However, because the single camera lens could not capture everything, I couldn’t completely follow the path of the gun. That approach would have ascribed too much cohesiveness to the proceedings anyway.

One of the typical dynamics we see here is the choice to react or not to react. This is related to a more specific dynamic: daring to fall and trusting that someone will catch you.

Note that, because all the tapes are labeled May 28, 1972, even though the series extended from May 28 to May 31, I am not 100 percent sure this video was the first performance, or even whether it encompassed one whole performance.

Yvonne, wearing big, billowy Indian pants and a sun visor, is dancing to the calypso beat of Harry Nilsson’s song “Put the Lime in the Coconut.” She’s holding Barbara with one hand and holding Steve, who is twisting and turning on the floor, with the other. Thus connected, she’s loosely, even carelessly, bopping to the music. Perhaps she’s taking the lyrics of the song literally: “You’re such a silly woman.” A toy gun falls from her clothing and clatters to the floor.

Steve reaches for it, grabs it, and drags himself on his forearms. David, wearing coveralls and sunglasses, saunters by, hands in pockets.

Yvonne is wheeling her arms in big, sagittal circles. Barbara steers Yvonne from behind as they windmill their arms together. They end the song with gentle hip bumping.

The Nilsson album has moved on to “Let the Good Times Roll.” (The Nilsson Schmilsson album, which had come out that year, was a favorite.)

Each dancer absorbs the song differently: Trisha, standing, just turns her head from side to side as in “no.” Steve and David stroll back and forth, shoulder to shoulder, or back to front, both with a supercool, noirish deadpan. When Steve changes his angle, so does David. Steve repeatedly extends the gun toward David, who turns away each time.

∎

Barbara, hands on hips, stops dead in her tracks and looks right at Steve, who is standing still. Nancy and Yvonne also pause. Trisha comes over and puts the gun (which Steve must have let go of at some point) into Steve’s hand and walks away. David goes to Steve, who is still still. He places a hand on Steve’s right arm, the one holding the gun. No one moves. Steve slowly keels over sideways to the floor in one solid plank. It’s hard to see in the video, but David has lowered him to the ground.

The song is now “Jump into the Fire,” with the insistent lyrics, “We can make each other happy.” Nancy picks up a paper airplane from the floor and sends it sailing toward the audience.

Barbara, with hands still on hips, turns her head away from Steve, toward the camera. (Trisha still has her back to the camera.) When Barbara realizes the cameraperson is focusing on her, she slowly turns her whole body to face our direction. With a half Zen-like, half impish expression, she seems to invite the camera to zoom in, which it does for about thirty seconds. As the camera zooms out, Barbara slips behind Trisha, creating an eclipse of her own face.

David has bent over to look at Steve lying still, as though trying to solve a mystery. He picks the gun up from the floor. Nancy looks at Steve, takes off her long, below-the-knee sweater, and covers him with it. David gives the gun to Yvonne, who tucks it into her trousers.

The song has segued into drumming, no vocals. Nancy, standing over “dead” Steve, begins shaking to the beat. She works herself up to a feverish pitch, like a medicine man exorcising spirits.

A few feet away, Trisha is on the floor, belly down, in solidarity with Steve. David lifts Trisha to standing, all in one plank, similar to the way he lowered Steve. She falls back on him again, and he lifts her again.

Yvonne slowly extends the gun into the vicinity of Nancy’s vibrational dance. Nancy, head down, is oblivious of this gesture until it actually intercepts her. She takes the toy gun, casually points it to her left, clicks the trigger, and hands it back to Yvonne. [Laughter.] Nancy resumes her manic solo to the point where her whole body is undulating and she’s blowing out of puffed-up cheeks. A virtuoso shaker, convulsive but shimmery, she’s in the zone. She’s making a one-time-only dance that escalates beautifully and finally subsides to just her wrists twisting in and out around her hips.

The gun click seems to have awakened Steve, who crawls, reptile-like, then gradually rises until he’s walking, still shrouded under Nancy’s hooded sweater.

∎

Trisha crouches on the floor, with David sitting nearby. Three times she touches her head to the floor, as though bowing, then sits back up. She gently pulls David to the floor, belly-up, in front of her. This time, when she puts her head to the floor, his chest is there to cushion her. With her face on his chest-pillow, she looks like a peaceful child.

Now on their hands and knees, Trisha and David playfully pull each other’s heads down. They grab each other’s supporting arms to make the body buckle. Trisha takes keys from her pocket and throws them down. David puts them in his pocket, then finds a piece of crumpled paper in his other pocket and lays it down. She picks it up and tucks it into her shirt. He puts down the keys. They are goading each other like dogs in a dog run. She points over her shoulder, then runs around and lands on his back, sidesaddle, toppling him. They slide, dive, and pounce, all the while keeping their eyes on each other. In the next playful chase, Trisha grabs a heavy, clanking chain from a small mound of props near a pillar—probably Yvonne’s stash of stuff.

Yvonne inserts herself into the space between Trisha and David. She points to Trisha accusingly, then grabs the chain and makes off with it. She reenters their playing field and steps on the crumpled paper that is an object of contention between Trisha and David. Like a cat that needs no preparation, Trisha bounds up onto Yvonne’s shoulders. Shocked, Yvonne lets out a long, foghorn-sounding yell as though calling foul.

Back to the dogfight with David, Trisha throws down the wad of paper. David ambushes Trisha, grabbing her by the shoulders and throwing her to the ground. The wind knocked out of her, she gasps. Yvonne gets in the middle again. Trisha leaps over Yvonne to get to David. Yvonne ties the chain around one leg and, thus hampered, tries to jump back into the fray.

Steve saunters by with a casual air, creating a shift in tone. David and Trisha start walking too. Trisha walks casually in a big circle while fixing her sleeve. The aggressions are over. Or are they? Suddenly she grabs David and flings him to the floor, as if he were light as a feather, then resumes walking and adjusting her sleeve as though nothing had happened.

∎

David and Steve stand facing each other. Trisha kneels between them. David is panting, hyperventilating in a steady rhythm. The moment Trisha looks up at him, he stops. When she turns away, he pants again. She points prayer hands toward him and he stops again. As she rises, he resumes panting, and when she taps his nose with her finger, he stops again. She holds David’s chin in her palm; Steve looks on in bemusement. David’s hyperventilating turns into laughing. Trisha and Steve join in the laughter, but she still has full control. The second she closes her mouth, David’s mirth disappears. Steve, less susceptible to her control, keeps laughing.

Trisha and David’s active/passive game is echoed by Barbara and Nancy a few feet away. As Barbara opens packets of white powder (sugar? salt?) and pours the contents onto Nancy lying on the floor, Nancy writhes exactly in time with David’s panting, and she goes limp when he stops.

Trisha coaxes her little circle, which now includes Yvonne, to laugh instead of pant. Soon enough, Yvonne’s laughter turns to wailing. Steve, David, and Trisha all laugh and start to bounce like monkeys. Yvonne, wailing even louder, has turned her back. The others work themselves into a cacophonous hysteria.

∎

Barbara goes off and starts dancing alone. Yvonne yells, “Barbara, Barbara, this is your line! Say it, say it!” Barbara doesn’t know what she’s talking about. Yvonne vehemently points to a line on a piece of paper. Trisha sticks the paper to her own forehead.

Yvonne to Barbara: “This is your cue.” She points to the paper on Trisha’s face. Responding to Yvonne’s urgency, Barbara stamps and faces Trisha while silently telling her off.

David butts in and tries to kiss Barbara, who pushes him away. While she returns to silently scolding Trisha, David tackles Barbara again. Her defense now turns to offense. When she pushes him this time, they stay glued together, scampering/galloping in a big circle, crazily linked to each other, getting all worked up. She’s hanging on him and jumping off of him, and he’s agitated and hyperventilating. Trisha claps and stomps, hootenanny style, adding to the melee.

∎

Standing in a ragged line, they all rearrange their clothes, tying shirts, changing headgear. Steve, Nancy, and Trisha, softly linked to each other, take a step forward. Yvonne motions enthusiastically to David to come to her spot in the line. David laughs/pants, hysterically reaching out toward the others. He can’t stop himself. Barbara tackles David again, and then, when he’s on the ground, she kisses him on the mouth. The kiss calms him; they are quiet and still. She starts to tickle him, which triggers another bout of panting.

Barbara and David recover and sit up. He has regained his composure and places a hand on her shoulder.

David to Barbara: “I really want to thank you for that. You really helped me. They stood there and they didn’t help me.”

Trisha, from her place in the line: “I was thinking about you, David.”

David: “But you didn’t help. She really helped. That’s the thing about Barbara. Everybody else stands around and watches what’s going on…. Barbara is willing to come out of the line. That’s a hard thing to leave: a line. Barbara is willing to come out of a line and help a friend.”

Yvonne: “She didn’t leave the line. She left me!”

David: “You mean, she abandoned you.”

Yvonne: “Yes, David.”

∎

Barbara and Trisha are trying out daredevil variations of a gymnastic flying angel. Barbara is squashed on the floor, face down. Trisha mounts Barbara’s upper back like a frog and balances for a second; a few in the audience clap as though it’s an acrobatic stunt. She falls back down. Barbara gets up to walk, holding her crotch. [Laughter.] David concentrates on pulling Nancy, who is lying down, through his legs. There are two couples now: Trisha and Barbara, and David and Nancy.

Barbara and Trisha try their trick again.

Barbara: “This is it!” They cave in. “That was almost it.”

Trying again. They both understand what the goal is, even if the rest of us don’t. When Barbara leans forward, it crunches Trisha’s knees so much that Trisha blurts out, “Barbara!” They collapse, then switch positions. (Steve stands by, eating from a Chinese takeout container with chopsticks.) Trisha bends way forward in a low squat. Barbara steps onto her lower back, stands up high, and starts doing demi pliés. [Laughter.]

Trisha: “OK, Barbara, come on back down.”

Steve and David watch from either side.

David gradually comes up to sitting and drags himself across the floor sideways. Nancy is holding onto his leg, her left arm wrapped around his shoulder.

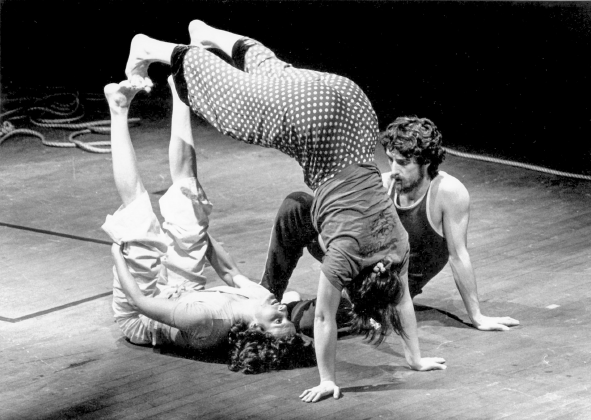

GU in Seibu Theatre, Tokyo, 1975. From left: Brown; Dilley; Paxton, who is narrating “The camel sees its reflection.” Photo: Courtesy Douglas Dunn.

David: “Nancy you’re a real drag.” [Laughter at this obvious pun.]

Nancy: “But I love you.”

∎

Trisha raises one foot to Steve’s abdomen while he’s eating from the takeout box. Barbara tries to jump over her leg, pushing down on Trisha’s head for leverage. Then Trisha plants both feet on Steve’s stomach while her arms are on the ground, her body forming an L-shaped handstand. Barbara slides and rolls under the bridge made by Trisha’s legs.

A lull. No one feels any compunction to make something happen. Trisha is leaning against a column. Barbara goes over to her, takes Trisha’s head in her hands, and gives her a kiss. As she walks away we see a toddler enter the space, watching David and Nancy. Nilsson’s lyrics are now “I can’t live if living is without you. I can’t give any more.” Barbara returns to Trisha and nestles between Trisha and the column. Trisha’s hands slowly come to rest on Barbara’s upper back. Barbara extricates herself and walks away. Trisha leans her head toward the column, and Steve leans against the same column from the other side. A poignant moment. A minimalist nuzzle intercepted by a barrier.

We hear the same Nilsson song that opened the proceedings: “Coconut,” with its tantalizing calypso beat. Steve, who has set down his takeout container, is feeling it; he’s moving to the music, soft and cool. David is rolling on the floor with Nancy holding his feet. He connects with Trisha’s extended leg, forming a linked-up diagonal line of Trisha standing at the column, David and Nancy on the ground. Steve continues dancing as he leaves the camera’s frame.

DIANNE MCINTYRE AND SOUNDS IN MOTION

In a parallel world to Grand Union, Dianne McIntyre’s Sounds in Motion, a company of dancers and musicians, was thriving in a different part of town. She performed often at Clark Center and The Cubiculo, small midtown venues, and she had a studio in Harlem. Much of her work was improvised, but she chose not to divulge that fact to her audience. She collaborated with many jazz musicians, including Cecil Taylor, known for complex compositions and polyrhythmic improvisations. (As mentioned in chapter 1, Taylor played in the first Judson dance concert.) McIntyre has been recognized as a pioneer who opened the way for other black women in contemporary dance. When I saw In Living Color (1988), a collaboration between McIntyre and musician Olu Dara, I was moved by the emotional intensity and impressed by how the performers wove together movement, music, and story.

In a public forum at New York Live Arts in 2014, McIntyre said she never told her audiences that she was improvising because they would think her dancers were “just doodling around on the stage.” She also implied that white groups like Grand Union had the privilege of being open about their use of improvisation.1

It’s true that any mostly white group has many privileges. But white dance artists like Anna Halprin and Trisha Brown have also bemoaned the fact that improvisation is not respected. In any case, I wanted to learn more about Dianne’s experience and perceptions, so I asked to interview her. In January 2018, we sat down together and I learned about improvisation from her perspective. We started off with her memory of seeing Grand Union, and then we proceeded to her own work, which has continued to grow and change. The following is adapted from what Dianne said that day.

I saw Grand Union around 1973. I was doing improvisation too. I was taken by the fact that it was improvisational and yet had such innate structure. All the people were choreographers who could structure a piece in a traditional way, so when they all came together that’s what it looked like. If you didn’t know, you could just walk in and feel it was choreographed by someone. They had a unity of mind and spirit. And the daringness of where they would go. All of that was interesting. Wow, and then to know that that was not going to happen again! I saw them in one performance where some of them were completely nude—or perhaps partially nude. In that time, nudity happened in other types of performances as well—theater, on-site gallery performances, etc. I guess it was a political statement—an expression of freedom from restrictions, as improvisation is that freedom.

In music, in the so-called jazz field, there’s a tradition that improvisation is a part of your greatness. (I say “so-called” because a lot of musicians don’t like their work put in a box. In the seventies, they just called it “the music.”) Improvising on a theme is greatly applauded. In your jazz conservatories, you practiced that. Some music students memorized recordings of improvisations of great musicians in order to learn how to get better as improvisers. Some of the musicians I work with call it “spontaneous compositions”; it gives a little bit more heft to it.

In modern, contemporary, or concert dance, it was not a skill that people trained for. I was very interested in improvisation. I had two teachers, Judith Dunn and Bill Dixon, at The Ohio State University around 1967 or 1968. They were my inspiration. They were there for a three-week workshop and that’s how I first became introduced to improvisation. She taught technique classes, which were basically like Cunningham, and they taught composition and improvisation together. There was something about it that caught fire in me. I just loved the improvisational experience.

In composition class, they made us jump out of the box in terms of our creativity. First Judith would give us solo studies; some of the studies were not related to how fabulous your movement was. In the time studies, we had to do a certain amount of movement within thirty seconds or sixty seconds. But we were not given go or stop. We must develop what she called “inner time consciousness,” not on a metered time. Then we had a study she called “The Fifties”: we had to do fifty movements in thirty seconds. You yourself defined what one movement was. We had to know when thirty seconds were over. The Fifties made you move without thinking, without predetermining your movement. We had, after maybe an hour and a half, built up some kind of understanding of creating our own movement with clarity and freedom and also your relationship with other people in a very high-quality way. It was almost like you were in a conservatory for music or in a ballet class learning how to do a pirouette: you repeat and repeat that until you can be steady. So these studies made us stronger and stronger in creating spontaneously. By the end of the class, after we had built up the muscle for it, we were doing totally free studies with no assignment at all.

I was so taken by their work that I came to their workshop in New York. I remember after one study, Bill said, “Why do you have to do everything in the world in one study?” That was my note. I guess I was just overenthusiastic, but it was a good lesson.

One year I also took a summer workshop with the Nikolais company at the University of South Florida, Tampa. Nikolais worked with elements of movement: shape, levels, time, traveling, dynamics. I liked it, along with the improvisation, because it did not lock me into a particular style. When I came to New York I studied with them and with Viola Farber. I liked Viola for building strong technique, expansive lines, and the mental capacity to remember her combinations on the spot.

With Bill Dixon and Judith Dunn, they had that collaborative connection with dance and music. That’s what caught me also, not just the improvisation; it was with the music. Their connection was more Cunninghamesque: they were in the same space, but they were not literally connected. It was a more atmospheric connection, one that we the audience were not privy to. It was stunning and very beautiful.

But I was interested in the dance and the music being part of the same band, the same ensemble, so there is a definite connection. Bill Dixon’s music was called “new music” or “free jazz.” I became enamored of that genre of music and I felt it had an openness that could connect with dance. When I arrived in New York I was going to different clubs and community centers and lofts to hear the music.

I met some musicians who were rehearsing in a day-care center in Brooklyn; they were called the Master Brotherhood. I asked them if it would be OK if I’d go off into a corner and do movement while they were rehearsing. They were like, Sure, it’s OK. I practiced moving like they sounded. When they would take solos, I tried to move like their instrument sounded and tried to do the same runs, say, the sax was playing, or the same lyricism of the piano.

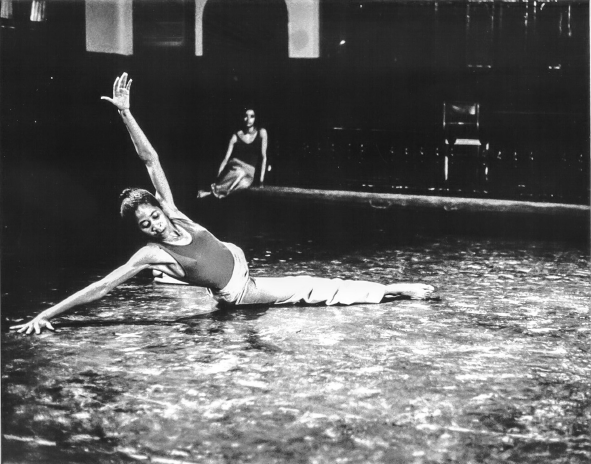

Dianne McIntyre of Sounds in Motion in A Free Thing, Washington Square Church, NYC, 1972. With Dorian Williams (Byrd) upstage. Photo: Personal collection of Dianne McIntyre.

That era, 1970–1971, was a period of protest and revolution in young people and in the arts and music. So this was in their music, even though they didn’t have any lyrics that might be called “resistance.” Their resistance was in the music, and the history of African influences were in the music, the blues.

After I did a solo called Melting Song at Clark Center’s New Choreographers Concert in 1971, I told Louise Roberts, longtime director of Clark Center, I was planning to have a concert at The Cubiculo, and she said I could rehearse at Clark Center. Very nice. I got a group of dancers together and invited some musicians from the Master Brotherhood. Part of the audition for my concert was that I had the dancers improvise with a couple of the musicians just cold.

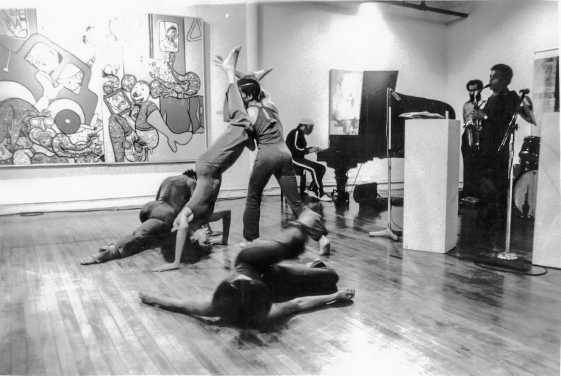

Rehearsal of Sounds in Motion, directed by Dianne McIntyre, Studio Museum in Harlem, 1980. Dancers: Cheryl Banks (Smith), Mickey Davidson, Bernadine Jennings, McIntyre. Cecil Taylor Unit: Cecil Taylor (piano), Ramsey Ameen (violin), Jimmy Lyons (saxophone). Photo: Personal collection of Dianne McIntyre.

There was a disconnect—perhaps that’s too strong a word. There was, and has been, separate dance communities related to cultural background. I had a certain kind of following that had a lot to do with being African American. There were people who didn’t see my work because it was like in another world. Over quite a few years I was produced by Clark Center, and those dancers, teachers, and supporters were the first people who were following my work. A lot of them were black dancers, actors, gypsies. I was also doing work in theater. Ntozake Shange was my student, and she met some of the early Colored Girls performers in my studio. [The full title of Shange’s acclaimed 1976 play is for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf.]

One of the first productions I choreographed for the Negro Ensemble Company was The Great MacDaddy. I met a number of people like Phylicia Rashad, Barbara Montgomery, Cleavon Little, Al Freeman Jr., and Lynn Whitfield. I have a connection over the years with people in black theater, and then there’s the music people. The audience evolved from those connections. Even though I did performances in main dance venues all over New York, those people would be following me. I didn’t have what you call the downtown dance crowd, even though the press always followed my work.

I danced for several years with Gus Solomons. Although he had come from the Cunningham tradition, his choreography had a more organic feeling. Some of my inspiration also came from Gus. I wanted to be experimental. Gus flowed back and forth between the black dance artists and downtown. He was able to go beyond that disconnect.

I rehearsed my company, Sounds in Motion, and conducted dance classes in Harlem beginning in 1974. After I renovated a space and established my own studio in 1978 at 125th and Lenox, I also began producing work of other dance artists—as well as some musicians, poets, playwrights. Jawole was one of my students—and my right-hand assistant. [Jawole Willa Jo Zollar went on to form Urban Bush Women, the award-winning company that weaves storytelling, usually about African American lives, into choreography.] I met her at Florida State University when I was doing a residence there. She came to New York to study with me. I was a mentor to her, though she was already a fine choreographer. My rule for whatever they were doing—and sometimes I was the person who would give feedback—was that the piece had to be daring. And you try, if possible, to use live music. The concerts were open to everybody to be presented, but white people were a little nervous to come to Harlem. Each year in our studio works series, Jawole did little pieces, and eventually she did a whole evening, with women who were our students at the studio. That concert had the feeling of what became Urban Bush Women.

I met Nancy Stark Smith at Bates in 2008. She was surprised that I had been inspired by Judith Dunn and Bill Dixon and that we had a common background. We did a wonderful improvisation session at Bates. Bebe Miller was in it too. That was special because we were all on the same page.