PUBLIC/PRIVATE, REAL/NOT REAL

How much of the Grand Union members’ personal lives spilled over into performance? Did they always remain “themselves,” or did they take on other “personae”? Is there a “real self” that is separate from the performing self?

It’s slippery to talk about the “real selves” of Grand Union’s performers, as some critics have. This was not a group that laid down ground rules about how to proceed or identify what was off limits. However, they did share certain unspoken understandings. Most of them had made dances at Judson, most (though a different most) had lived in SoHo, and most (yet a different most) had worked with Yvonne on CP-AD. These were all long-term, burnishing experiences.

One of the shared understandings was to make the process visible to the audience. As Sally Banes has written, “Part of its risk-taking was to lay both the process of improvisation and the process of group dynamics open at all times to public scrutiny in performance.”1 If they needed a sofa to complete a scene, they dragged one across the stage. If they disagreed about when to take an intermission, they bickered onstage. These were real tasks and real discussions that allowed the audience to see them navigate their needs and desires. The magic of illusion was not part of it. (The magic existed elsewhere.)

Illusion, that keystone of theatricality, was hard to let go of for some critics. In 1963, Dance Magazine reviewer Marcia Marks had written about a James Waring concert: “When David Gordon and Yvonne Rainer began calling each other by name, the last illusion that this might be a public performance was shattered. The evening slipped solidly into focus as a staging of private jokes, private psychoses.”2

Marks was not the only critic who felt uninvited, uninitiated, or offended by the personal nature of downtown performances. When Grand Union came to Minneapolis, critic Allen Robertson accused the performers of ego-tripping (while parenthetically wondering, “Maybe all improvs are ego-trips?”).3 Dance Scope editor Richard Lorber was annoyed by what he felt was a contradiction: “They disdain the ‘exploitation of personality,’ or the ‘star system,’ yet they focus audience attention completely on the naked spontaneity of individuals. We come away with a heightened sense of their personal exhibitionism.”4

The Nation’s Nancy Goldner, one of the many American critics devoted to Balanchine’s work, believed that “Grand Union banks on the cult of personality.”5 Well, yes, the GU dancers wore their own clothes and danced from their own impulses. Their personalities were not attached to (or recently detached from) a genius choreographer. This autonomy may have offended ballet critics who were accustomed to seeing dancers wearing identical costumes while performing a master’s choreography.

As downtown denizens, we soaked up the independence of the GU dancers and the breakdown of illusion. We liked watching them be more or less the same people we knew through taking their workshops or seeing them around the neighborhood. We watched with curiosity, wondering what absurdist yarn David would spin, how Barbara would assert herself (in those prefeminist days), exactly how Steve would deflate a dramatic situation, how Nancy would go along with something but add an unexpected flourish, what outlandish feat Douglas would attempt, or what brilliant idea Trisha would come up with. And how they would fall in with—or resist—each other.

All their actions were based on a continuum of “real self” and “performed self.” Words like “character” and “identity” were often used by critics trying to decipher the relationship between the person and the performer. To give an example of two opposing perceptions, the artist and sometime critic Robert Morris wrote that Grand Union was “a collection of individuals who never lose their identity,”6 while dance scholar Susan Foster claimed that “each performer acquired a variety of personae…. None of these characters could be equated with the true identity of the performer.”7

I think dance critic Marcia B. Siegel put it more poetically. After seeing the 1975 La MaMa show, she wrote, “Six people have agreed to come together and live a part of their lives in public.”8 I don’t think this description is entirely accurate either, because these improvisers consciously shaped what they did as performance. But Siegel’s statement comes closer to the spirit of Grand Union. The dancers were willing to enter a performance the way they would participate in their own lives: doing tasks, making alliances, taking a chance, engaging in play, taking a break. Valuing the art in the everyday, the everyday in art.

This Cagean meshing of art and everyday life, which was so key to the tenor of the sixties, could be misconstrued as narcissistic. Jack Anderson, looking back on this period years later, points out a paradox in how this alleged narcissism developed: “[I]n contemporary abstract dances performers often appear to be declaring, ‘We are ourselves and we’re here to dance.’ This insistence … has sometimes been branded as narcissistic. Yet it arose to counter what was regarded as the egotistical pretension of an earlier era.”9

The pretension he refers to is exactly what Rainer railed against in her “rage at the narcissism of traditional dancing,” mentioned in chapter 3 (note 16). She chipped away at that narcissism by giving dancers tasks that made them vulnerable, for example having to learn a new sequence in public. This kind of self-exposure was carried into Grand Union exponentially. No one ever knew what was going to happen. And, as Trisha had said at a gathering of critics and Grand Union dancers, “The tiredness shows, and the confusion.”10

But what also shows is their caring for each other. At one of the 1975 La MaMa performances, after Trisha dismounted from a ladder that had been supported for a long time by Steve lying on his back, she massaged his legs. As we saw in the Iowa video, Barbara apologized for inadvertently digging her heel into Douglas’s lower back when he was crawling underneath her standing weight. At Oberlin, when Nancy was thrashing around as a crazed rock-star-turned-crazed-dancer, David wrapped her in silk and hugged her. Many years later, Nancy cherished that moment: “David put his arms around me and held me tight. He silenced me and calmed me, which I needed. It was beautiful.”11

∎

For critics to say that Grand Union dancers were either always themselves or never themselves is misleading. Each person was different in this regard. David, with his fondness for radio and television, easily slipped into different characters; he found willing accomplices in Nancy and Barbara. Nancy could interrupt her own whirlwind dancing to serve in any far-fetched plot of David’s. In fact, she would sometimes initiate a reprise, for instance the farmer’s wife desperately yelling to save the crops, as she did in Iowa. She would do so with obvious “bad acting” so no one would ever accuse her of “inhabiting” a role. Her usual goofy/elegant self remained firmly in place. David could pass through being a water detector, a surgeon, and a circus barker in a single performance. But it was his actions, not his acting, that brought him there. For instance, when he held his hands up as though wearing sterilized gloves for an operation, he didn’t do method acting to convince you he was a surgeon. (More about this episode later.) It was the gesture itself that suggested the character. Douglas could put on a cowboy hat and make you imagine he was sleeping under the stars. But again, it was just an indication, not a theatrical transformation—or maybe it was just enough of a transformation to allow the audience to use its own imagination.

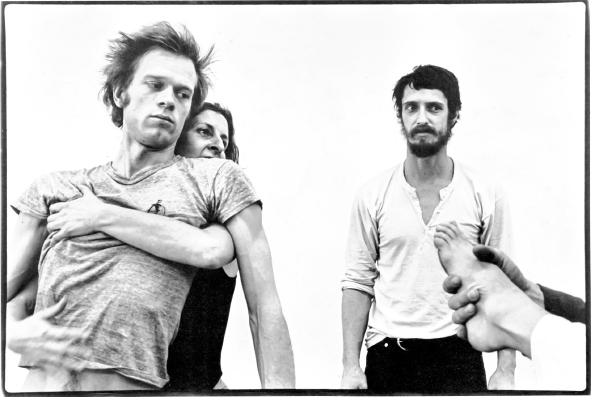

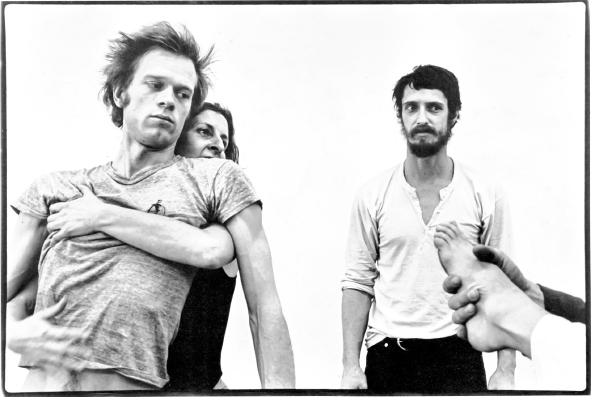

GU in Trisha Brown’s loft, in “rehearsal,” June 1975. From left: Dunn, Brown, Paxton, Gordon’s hand, Lewis’s foot. Photo: Robert Alexander Papers, Special Collections, New York University.

Steve and Trisha were more stalwart in being dance-based rather than character-based. When Steve donned a sarong for one of the La MaMa performances, he didn’t adjust his actions to be more feminine or more Asian. Trisha could imitate a monster for five seconds, but it was mostly to make a point. Yvonne could delve into emotional extremes, but not in a character sense. When at LoGiudice Gallery she escalated the volume and intensity of her calls to “Ma. Ma-a. Mama,” she might have been recalling a moment from childhood or releasing an adult cry for help rather than acting out a character.

When the issue came up in our group interview, Steve railed against the implication, from theorists like Foster, that a “real self” or “true identity” exists separately from a performing self. Yvonne, on the other hand, sees a difference between performing a mundane task at home and doing the same task in public: “When you have eyes upon you, something does happen to you…. You’re not aware of yourself when you’re washing the dishes [at home]; you’re only aware of the task. If you’re washing the dishes with people looking at you, you are aware of both: being looked at and the task. So there is a difference.”12

But even for Yvonne, it’s a difference of awareness, rather than a difference of one mode being more “real” than the other. For performers, who spend much of their professional lives in front of an audience, it’s not particularly constructive to call one behavior real and the other not real. Many dancers feel most “themselves” when they are performing.

The question comes up about David and all his getups. Was he trying to erase himself and become a different person? Sally Sommer, who saw many GU performances, feels that his escapades were more about play, not about inhabiting a character the way an actor would.13 Yet he admits he felt buoyed by the possibility of escaping himself—even without a costume as disguise: “One of the things I could do at the Grand Union is I could become not me…. I didn’t have to change costume, I didn’t have to do anything. All I had to do was announce I wasn’t me and now I was somebody else and now we would play with whoever it was.”14 (Notice the verb “play.”) Yet like Steve, David said he had no interest in teasing out the difference between an alleged “real self” and his play selves.15

∎

Here’s an example of a private mishap that grew into a public narrative. Just before one of the La MaMa performances, David had a back spasm so bad that he couldn’t stand up. He had sought help from Elaine Summers, who lived in the building next door, to work on him with her ball work and other healing methods. When he arrived at La MaMa, he appealed to his fellow dancers to be gentle with him, and they presumably agreed.16 But midway through, in response to a kind of scratch-fest between David, Barbara, and Trisha, Barbara jumped onto David’s back. Instead of squawking, David at first played along, reversing his real sensation: “Hey, oh hey. This is more like it.” Then, getting his bearings: “We made an agreement and now the agreement is broken.” Realizing what she had done, Barbara confessed softly: “I broke the agreement.” After Douglas lifted her off David’s back, she sighed, “Oh David.” David joked, “You couldn’t keep off my lower back. You gotta get your hands on it!” He then proposed that, in order to rebalance his body, Barbara should now jump on his front. (David was a master at devising opposites.) Barbara expressed nervousness, and Douglas and Steve got involved in what became a beautifully coordinated attempt at forgiveness.

To a certain extent, the dancers always played themselves. Douglas was the youngest in the group (after Lincoln Scott left) and often behaved that way. He took physical risks that typically the young take (balancing on a high beam, diving into a bucket of water). In life he tends to be a loner, and with Grand Union as well, he was happy to delve into solo investigations.

Likewise, Steve tends to be philosophical in life as well as in performance. But he also had a deep interest in exploring physical relationships through weight bearing: “I like it when bodies are free and when the emotional state is open and accepting and sensitive. When the psychology isn’t hassled or political or tied in knots. I like it when people can do things that surprise themselves. Where it comes from is just human play, human exchange—animal play. It’s like horseplay or kitten play or child’s play, as well.”17

Trisha had a way of speaking and pausing in real-life conversation, and this halting rhythm sometimes provided an uncanny suspense in Grand Union.

These are examples of how each person followed her or his own interests or tendencies while also remaining an essential part of the ensemble. No separation between private and public. Kathy Duncan, the dancer/writer who called the group “a collective genius” and “a utopian democracy,” said that “much of their success is due to the fact that they’re extremely interesting people and have learned to be themselves in the arena.”18

For some, these interesting people took on the patina of glamour. Experimental theater director Richard Foreman felt they possessed the charisma of Hollywood movie stars like Marlene Dietrich.19 Art critic Grace Glueck overheard an audience member calling Barbara Dilley and Steve Paxton “the Lee Remick and Paul Newman of the avant-garde.”20 Dance critic Nancy Dalva was quoted as saying about the Judson dancers, “One thing that people don’t really talk about is that … they were so hot!”21 This downtown allure was seen in a negative light by Goldner, who wrote, “Their appeal is similar to that of the Beatles; it’s possible to like them without giving a hoot for what they do.”22

But of course we did care what they did (just as we cared what the Beatles did). We wanted to see them over and over again. I don’t think Grand Union members cultivated their “personalities” any more than a visual artist or musician does. How they walked, how they moved, how they made connections—this is who they were as people. And, as Steve pointed out, they were their own material. Rather than utilizing technique or choreographic imagery as material, this was a refreshing way to be oneself in performance. After all, plenty of triple pirouettes and well-rehearsed musicality were on display elsewhere in the dance world.

Their access to their “play selves” was an essential component in Grand Union. For David, it had to do with the ability to weave stories. On his Archiveography site, he says that while in Grand Union, he discovered that “making up stories is improvising—and improvising is related to lying. David makes up stories or improvises. Or lies and invents the truth he needs—or wants—instead of the truth he has.”23

Douglas too is very clear about the plurality of options. On a lighter note than before, he cites both fantasy and reality as sources: “We all just made up stuff and we all became verbal…. It was fun and very rich because it was full of fantasy and reality. You could say something about what happened with Barbara yesterday and it could be really personal stuff and you had to stay in character and make it a story and not worry that there’s some truth that’s gonna have personal import to you. You’re just gonna follow it and use as much as you want of what’s real and what’s not real. It was fantastic.24

GU at LoGiudice Gallery, 1972. From left: Dilley, Paxton. Photo: Gordon Mumma.

This shifting back and forth between fantasy and reality contributed, as Barbara has said, “to letting [the unconscious] have a priority, and letting out the kook or the demon or the queen or the whore or the dumb bunny or the smart cookie.”25 She gives credit to David for this fertile strand of improvisation: “There was a lot of projection on one another…. We would build it up and then dissolve it on the spot…. We took on personas with each other, and David was a very rich teacher in that way for me. He would somehow generate a little situation in which he communicated what persona I [would have] and then I made the agreement to [get] into that persona.”26

For Barbara, what she calls “character work” was a stretch at first, but she became skilled at it. It was only possible, she felt, if she let the unconscious have free rein. And this was only possible because Grand Union had learned a central concept of theater improv: that play is how you get to the unconscious.27

But this unruly play had its dangers. It was never clear whether there was any separation between the “play self” or “other selves” and the person. Again, from Barbara:

We were spending a lot of time together in this kind of wild, unpredictable universe and our other selves were showing up. I was not always sure whether we were performing or not…. David … had this ability … to create a scene. He was offering me a character and I would assume the character work, and then we would play together and sometimes we would get angry with each other. In this [one] particular scene, he was teaching me to sing opera; he was coaching me in an operatic event of some kind. I was going along with it. I was wailing away, singing opera and he was criticizing me, saying, “Do it differently.” And at some point, I turned to him in my operatic majesty and sang, “I hate youuuuu [singing].” Afterwards … David came up to me and said, “I think you meant that.” I looked at him and I didn’t know what to say. I mean, I didn’t know whether I meant it or not. At the moment I meant it, but I didn’t mean it now. It was a very turbulent environment … when those personal situations were happening—what was really being revealed and how much could we tolerate it. I felt like I was totally inhabiting the persona…. David and I were not ourselves, but were we, or were we not? It got a little murky sometimes.28

For some of us in the audience, that murky area was intriguing. As Robb Baker wrote after seeing a string of Grand Union performances in 1974, “That very no man’s land between public and private, between performance and life, is exactly the area explored most fascinatingly in this grand union.” 29

LEADERLESS? REALLY?

What kind of organization survives without a leader? We often expect such a group to descend into chaos. But it is possible to operate collectively, more or less—for six years anyway.

Even though the counterculture was rife with communes, it was rare for an arts group to be completely communal or democratic. The long-running participatory arts groups have had leaders: Bread & Puppet Theater has Peter Schumann, the Living Theatre had Judith Malina and Julian Beck, the San Francisco Mime Troupe had R. G. Davis. Loose collectives like Fluxus, which was transatlantic with the crazy George Maciunas as head of it, and Arte Povera in Italy, were short lived. The same was true of Judson Dance Theater and artist-run galleries like Hansa and 112 Greene Street.

But Grand Union was a tight-knit group compared to those loose collectives. The members didn’t just share space; they were cocreating as equals in every performance. In a way, it was the culmination of the egalitarian impulse, the ultimate democracy’s body, to borrow Sally Banes’s term. They physically committed themselves to group process, to listening to each other with their bodies. They were focused on a creative exchange rather than excelling in the eyes of a director.

Even offstage, Grand Union was a democracy. The performers shared administrative duties like corresponding with presenters and applying for grants. In 1972, Artservices International, the main European booking agent for the American avant-garde, branched out to New York. (Artservices, led by Benedicte Pesle in France, handled Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Robert Wilson, and others. The list grew to include Trisha Brown Dance Company and Douglas Dunn and Dancers as well as the Cage-influenced Sonic Arts Union.) The young American Mimi Johnson, whose arts savvy was cultivated by Pesle in Paris, was sent to New York to start Artservices New York. Two of her first clients were John Cage and Grand Union. (Cage had befriended Johnson in Paris and personally invited her to New York.)1 The improvisers would designate one among them to deal with Artservices.2 Technical matters like lights and sound, which were minimal in the early years, were often handled by Steve and David. Then, in 1974, Bruce Hoover was hired as technical director, which made it more feasible for the group to play proscenium theaters.

Leadership during performances shifted continually. To quote Steve again, “Following or allowing oneself to lead is each member’s continual responsibility.”3 While watching Grand Union, audience members often imagined a leader or, in their minds, assigned a leader. About the February 1971 loft series, Pat Catterson (who kindly typed up her notes from seeing those early performances) wrote that she felt Barbara Dilley was emerging as a leader. Elizabeth Kendall, too, felt that Barbara “set the tone” and “presided over” the four performances she saw at La MaMa in 1976.4 Critic Marcia B. Siegel felt that Steve Paxton was “like the conscience of the group, and also a subliminal prime mover.”5 Mary Overlie would agree: “I always thought that Steve brought in the artistic vision. He was the person to set the intellectual tone of the evening.”6 Juliette Crump, who invited the group to the University of Montana at Missoula for its final performance, felt that David “was kind of the head of the company because he was the one who was talking the most.”7 Judy Padow, who had performed with Rainer and watched GU grow out of CP-AD, said, Rainer “was the major think tank behind the Grand Union. She was the one who was really experimenting with giving up choreographic control in favor of the kind of creativity that could be otherwise unleashed.”8 Carol Goodden, who was dancing with Trisha at the time, naturally felt that Trisha was “the star.”9 Perhaps the most even-handed observer was Mimi Johnson from Artservices. She said simply that Grand Union “was led by the people who were willing to actively lead.”10

Theresa Dickinson, the dancer who guested with Grand Union at the San Francisco Art Institute, saw the ensemble as truly leaderless, similar to the rock bands she later worked with. In the early seventies, she was a freelance camera assistant at San Francisco’s KQED television station, filming rock groups like Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, and Quicksilver Messenger Service. Dickinson, who as a Tharp dancer had lived in the same dorm with Rainer’s group in the summer of 1969 at Connecticut College, found an affinity between these bands and Grand Union: “I watched with amazement as the band members listened to each other and reacted in real time, producing unexpected turns and passages that were only of that moment. Before then, improvisation didn’t interest me. When I saw it as a way of making a work together, new every time because of shifting circumstances, it became exciting, even paramount. That message came to me from the Grand Union and the rock bands, all sharing the fervor of new growth in a searching, idealistic moment.”11

Grand Union members were not exempt from rock-star fantasies. Yvonne even said she sometimes felt that on tour, they were like a rock band.12 David had suggested that their publicity shots for Oberlin should look like those of a rock band.

But in a more grounded way, Dickinson’s observation rings true. In a band, each musician plays a different instrument, contributing a tone that helps complete the band’s unique sound. What I saw in Grand Union performances back then, as well as in the archival videos, was that each dancer was strikingly different, vividly herself or himself and essential to the whole. Each dancer contributed a different range of tones and textures to the group “sound.” In performance, the dancers allowed each other to evolve even further into their own selfhood. This brings to mind Douglas’s idea of the ideal world, where everyone was “trying to realize their individuality completely but in relation to other people, necessarily.”13 (Of course this is partly a theatrical illusion. I do know, through my many conversations with them, that there were times when some of the Grand Union dancers felt held back.)

The issue of leadership was merrily lampooned in Grand Union. In the 1976 La MaMa performance, Barbara, Nancy, and David are bouncing around like jumping beans at different paces. David slows down and stops while Barbara keeps going.

David to Barbara: “I can’t keep up with you.

Barbara: “You shouldn’t be tired.”

David: “I thought you were the leader,”

Nancy: “I thought I was the leader.”

David, pointing to Barbara. “She was the leader. I made her my leader, and I couldn’t keep up with my leader.” He bows down to her on the floor and covers his head.

Barbara, pointing to David: “What does a leader do with … ?”

David: “With the fallen people.” He starts crawling toward the still prancing Barbara. Barbara sits on the floor near David.

David sits up: “You know what makes a leader? A follower.”

Barbara: “I disagree. You know what makes a leader? Wisdom.”

David: “You’re my leader.” He crouches down and covers his head again.

Barbara: “Get up, follower. Follow me.”

She sways side to side, arms out. David gets behind her but doesn’t follow her arms. He ducks down to be her size, at which point Barbara tells him he has to stand tall.

Losing interest in this, David stands up and goes to join Valda, who has been studiously untangling a knot of string: “I’d like to be your follower.”

The concept of leaderlessness leads us to the concept of anarchism. The popularized notion of anarchy as sheer mayhem obscures the underlying humanity of this philosophy. The anarchists of France and Russia believed that cooperation is possible without government, that there is no conflict between individual desires and social instincts, and that government exists only to protect property and to control people by violence and suppression. Emma Goldman, the most charismatic anarchist of the early twentieth century, embraced the idea of an organized society not as coercion but “as the result of natural blending of common interests, brought about through voluntary adhesion.”14

It is perhaps not by chance that Yvonne started reading Goldman at age sixteen.15 The philosophy was part of her family background—she attended gatherings of Italian anarchists—but also she was interested in anything that gave off a whiff of rebellion. Anarchism had a meaning that dovetailed with the artistic ferment of the sixties. Yvonne called West Coast poets like Kenneth Rexroth and Kenneth Patchen “nominally anarchists.”16 Banes called John Cage, Jackson Mac Low, and Judith Malina and Julian Beck “anarchist-pacifists.”17 (Cage and the Beat poets were routinely labeled anarchists.) As we saw in chapter 2, Gordon Matta-Clark and some of the 112 Greene Street artists called themselves anarchitects. Artists tend to revere irreverence, so anarchism means something different, something more honorable, in the art world than it does in the usual American parlance.

Early on (probably in late 1971), when Grand Union hadn’t yet committed to total improvisation, the members wrote an explanation of their shifting position: “Currently we are thinking about organizing many of the ideas and images that emerged this winter into a new structure—partially set and partially improvised. The pendulum swing between anarchy and thru ‘modified democracy’ to oligarchy and back again, is being carefully observed by all of us.”18 To me, this means that they were aware of the larger implications of their decision making.

GU at Annenberg Center, University of Pennsylvania, 1974. From left: Brown, Dunn, Gordon, with Paxton on floor. Photo: Robert Alexander Papers, Special Collections, New York University.

Democracy is one ideal, but it retains a hierarchical order. The anti-authoritarian sentiment of anarchism envisions no one having power over anyone. Jill Johnston wrote of the Judson dance artists, “The new choreographers are outrageously invalidating the very nature of authority. The thinking behind the work goes beyond democracy into anarchy. No member outstanding. No body necessarily more beautiful than any other body. No movement necessarily more important or more beautiful than any other movement. It is, at last, seeing beyond our subjective tastes and conditioning … to a phenomenological understanding of the world.”19

Johnston watched Judson closely, almost keeping vigil over its discoveries. By the time Grand Union started, she was no longer writing about performance. It was her successor, Deborah Jowitt, who kept a similar vigil over Grand Union (though it was one of many interests for her). Each time she reviewed the group, new thoughts emerged. She was not a detached observer but was emotionally involved. In a 1975 review she wrote, “I spend two evenings at La MaMa … and come away absurdly comforted—thinking that if I stuck my head out the window and yelled to the street below, ‘catch me,’ maybe, just maybe, someone would.”20 She gives us a whiff of the anarchy—the good kind—that inspires a crazy level of trust.

Just as Yvonne was influenced by Goldman, Steve was influenced by anarchist philosopher Peter Kropotkin’s idea of mutual aid. In a response paper in 2014, he referred to Kropotkin’s research on animal societies that suggested the societies with the most mutual aid are also the most open to progress.21 The idea of mutuality, as we saw earlier, was foundational to Steve’s development of Contact Improvisation.

The formation of Grand Union in the fall of 1970 inspired Paxton to jot this down:

A dancer is both medium and artist.

It is time again to attempt anarchy. For one, anarchy is simple.

Anarchy for a group requires conditions of communication. The Grand Union is a blend of artists. A group. This is a basic theatrical form: a social group exploring the image and the cultural appurtenances. The social structure we are produces results, exerts control beyond our individual devinings [sic]. The point, of course, is theater, not anarchy. Occasionally it is good to work alone. Occasionally it is good to work together.

See, see how it comes apart.

See how it goes together.

The Union suits.

Steve Paxton

29 december 197022