EPILOGUE AND THREE LINGERING MOMENTS

Does Grand Union have a legacy? Is there a lineage that can be traced? Improvisation famously disappears after the moment of performance. One could point to the improvisation groups that sprouted up inspired by Grand Union: the Harry Martin Trio in Minneapolis, Tumbleweed in San Francisco (started by Theresa Dickinson), and three groups in New York City: the Natural History of the American Dancer, Central Notion Co., and Channel Z. Not to mention the myriad of Contact Improvisation networks and events. One could point to the growing number of college dance departments that offer some form of improvisation.1 Or the many books on the subject.2 But there is no way to know how much of this current burgeoning is due to Grand Union.

Perhaps the group’s legacy lies in who the long-term GU dancers are and what they have continued to do. After all, part of the reason Grand Union was called “epic” by Deborah Jowitt3 is the individual people involved. They were the bricks and mortar of postmodern dance. In that spirit, I provide here a quick update on each of the main players, including the traces of her or his work that continue to exist.

∎

The expanse of David Gordon’s career was revealed in the spring of 2017 when the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts mounted his Archiveography exhibit, which has now morphed into a comprehensive—and entertaining—website at davidgordon.nyc. David has created intimate works as well as large productions all over the country. For his United States (1988) at Brooklyn Academy of Music, he collected stories, music, and poems from twenty-seven presenters in seventeen states. The Archiveography website recounts, by the decade, David’s childhood memories, dances, scores, mishaps, happy coincidences, respect for Valda, and a few gems about Grand Union. It meshes his personal and professional lives, spinning his own form of narrative, just as he told his own stories within Grand Union. He sees the photography he studied in college, the store windows he designed, the proscenium stage, and his recent interest in creating graphics with blocks of words as all related to framing. In an email to me he acknowledged that commonality, saying, “The computer is my enda life rectangle.”4

Trisha Brown’s influence is recognized the world over. The promise of the Judson revolution has reached a choreographic peak with her works like Opal Loop (1980) and Set and Reset (1983). Major dance artists, like Bill T. Jones and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, admire her for inventing an entirely new dance vocabulary. She also developed new ways of organizing choreography, from the Accumulation series to her process of improvisation and recall that started with Line Up (1976) and Water Motor (1978). In addition, she broke conventions of stage performance, with the dance overflowing beyond the proscenium (Glacial Decoy, 1979) or the music emanating from outside the theater (Foray Forêt, 1990). She is beloved in Europe not only as a leading postmodernist but also as a director of innovative operas. Although she died in 2017, the Trisha Brown Dance Company is still in demand for giving workshops and for performances that often reimagine her early work in different spaces. Susan Rosenberg’s book Trisha Brown: Choreography as Visual Art traces Trisha’s connection to the art world, and an ArtPix DVD contains videos of her early work.5 The Trisha Brown Dance Company Archive, with thousands of photographs, videos, scores, sets, and costumes, has recently been acquired by the Jerome Robbins Dance Division of the NY Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Douglas Dunn has choreographed nonstop since Grand Union. He continues to perform in his studio in SoHo (where he also teaches), on the streets, and in small dance festivals. His major works include Gestures in Red (1975), Lazy Madge (1976), Pulcinella (1980) for the Paris Opera Ballet, and Stucco Moon (1992). He appeared in Michael Blackwood’s documentary Making Dances: Seven Post-Modern Choreographers, along with David Gordon and Trisha Brown. His long-term collaboration with visual artist Mimi Gross has yielded about fifteen vivid group works, including Echo (1980) and Sky Eye (1989). A book of his writings, Dancer Out of Sight, was published in 2012, and he has written for Dance Magazine and the art journal Tether. His website, www.douglasdunndance.com, includes a full chronology. As he said recently, “Now I want to make dances until I drop.”6

After spending ten years as the reluctant father/hero of Contact Improvisation, Steve Paxton went in a new, more choreographic direction. The imagery of his 1982 solo Bound at The Kitchen seared itself into my memory. He developed a collaboration with percussionist David Moss that fed the impulsiveness of his movement. The peak of his solo improvisation practice came with The Goldberg Variations (1986–1992), which was a sublimely articulated response to Glenn Gould’s rendition of Bach. Since then he has been developing his Material for the Spine—“to bring movement to consciousness”—in performance, video, and book form. His essays, interviews, and dialogues appear often in Contact Quarterly. The European organization ContreDanse has published a CD-ROM of his Material for the Spine and a slim compilation of his writings titled Gravity (2018). His long-term collaboration with fellow improviser Lisa Nelson yielded two spare, poetic evocations: PA RT (1983) with music by Robert Ashley, and Night Stand (2004). He now spends most of his time in his home in northern Vermont, surrounded by forest. As he said in a public talk at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018, “Every atom in the landscape in front of me that I look at every day is changing…. I feel like it’s a living soup and I’m … kind of dissolving into its space now.”7

In 1974 Barbara Dilley, along with poet Larry Fagin and Mary Overlie, cofounded the Danspace Project, located at St. Mark’s Church on the Lower East Side. Long a major force in the dance world, Danspace has welcomed Barbara back several times over the years. She also helped launch the movement program at the Buddhist-inspired Naropa University in Boulder and served as director of its dance program from 1974 to 1985. She devised scores for teaching improvisation and composition within her Contemplative Dance Practice, which mingles meditation and improvisation. She was so respected for her work there that was appointed president of Naropa, serving from 1985 to 1993. (Let’s see … how many women or dancers have become university presidents?) She continued making dances in projects like the Crystal Dance Company, the Mariposa Collective, Fearless Dancing Project, and the Naked Face Project. In 2009 she began gathering her memories and teaching strategies into a book titled This Very Moment: teaching, thinking, dancing (2015). In 2016 she retired, becoming professor emerita. The younger generation, she notes, has continued to adapt Contemplative Dance Practice’s ability to connect mind and body to their own lives.8 Toward the end of her book Barbara writes, “I am changing now and dancing is fading for me.”9 But her body consciousness is still a source of vitality. She is now exploring “how to be comfortably awake in my aging and not feel a victim of getting old.” 10

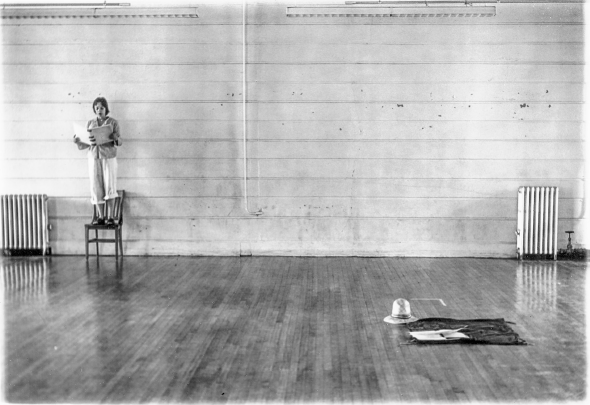

Barbara Dilley reading from a book by Agnes Martin to Naropa students, Boulder, CO, 1975. Photo: Rachel Homer.

Nancy Lewis met musician Richard Peck while he was playing in Philip Glass’s ensemble (as he continued to do for many years). They married in 1974 and performed together at venues like Dance Theater Workshop, Paula Cooper Gallery, and P.S. 1 in Queens (later annexed by the Museum of Modern Art). She had been invested in the collectivity of Grand Union and had no wish to start her own group or replicate the Grand Union experience in any way. After 9/11, she and Richard moved to Rhode Island, where she now does home healthcare work.

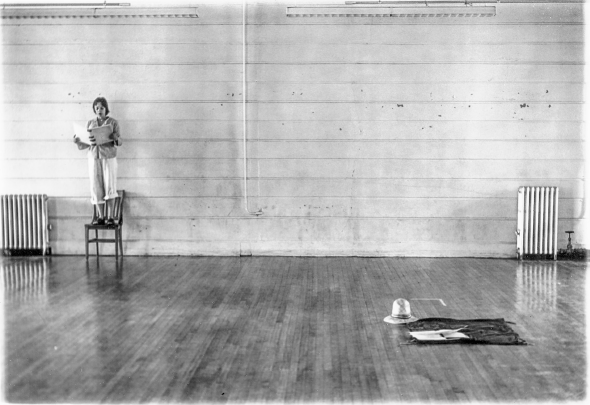

GU at NYC Dance Marathon, 14th Street Y, 1971. From left: Dilley, Gordon, Rainer, Brown. Visible in audience center, lying on the floor, Carolyn Brown; sitting behind her, James Klosty. Photo: Susan Horwitz, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

In her twenty-five-year detour from dance (roughly 1973 to 1998), Yvonne Rainer directed seven experimental films, earning acclaim as an early feminist filmmaker. She returned to dance in 2000 at the invitation of Mikhail Baryshnikov in a pilot project for his Past-Forward production commemorating Judson Dance Theater.11 Since then she has made about six full-length dance-and-text works and reconstructed the epic Parts of Some Sextets (1965), aka the Mattress Dance.12 Her company, which performs at museums, colleges, and international festivals, sometimes reprises her early works like Trio A and Three Seascapes. Yvonne has published an autobiography (Feelings Are Facts), many essays, and a book of poetry. Her classic book Yvonne Rainer: Work, 1961–1973 was recently reissued by Primary Information. Jack Walsh’s documentary film, Feelings Are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer, has garnered awards on the film circuit. (Disclosure: I am one of the commentators.) She continues to write provocative essays and continues to be a subject (sometimes target) that scholars in dance, art, and performance have to contend with.

But these achievements I have cited are separate from Grand Union’s legacy as a collective. It was a gathering of sublimely unruly spirits with no stated goal. But along the way, it invented a performance form that fused the freedom of childhood with an urban sensibility. It melded art and life in a way that captured the defiance, camaraderie, humor, and happenstance beauty of the time. And it sustained a trusting and democratic process for most of its six years.

I don’t know if a leaderless improvisation group could exist today. The seventies was a time when individual creativity could flourish within a collaborative ecosystem. The fantasies, explorations, dares, and subversions that tumbled out of Grand Union coalesced into an experience that many of us were hungry for at that time. And that experience allowed for a wide range of reactions and emotions, including contagious moments of sheer joy.

∎

I leave you with three memorable scenes that were not part of the narrative unfoldings.

LA MAMA 1975

Nancy stands, hands clasped behind her head, elbows outward, watching Steve and Douglas. They are lifting, hanging against, and dragging each other in a vigorous Contact Improvisation duet. Suddenly a narrow space opens up between them, and she simply steps into that space. Her left elbow is touching Steve’s nose. Douglas offers Steve his hand to keep the contact. Steve holds his hand while his nose gently guides Nancy’s elbow downward so her arms unfurl toward the ground; Steve and Douglas lower down, each of them circling their heads around one of her wrists, while she stays upright. Their heads hover in the nether regions of her torso. It’s a sexual image but also an image of a mother and two children. She looks straight ahead, but every pore of her skin senses what is happening. She tilts her head slightly as the two men stay crouching on either side of her.

LA MAMA, A DIFFERENT PERFORMANCE, 1975

David has been walking around with his hands held up, palms facing inward. Because of the position, a character comes into focus: a surgeon about to operate. This is a surgeon with a difference: he uses his teeth as a scalpel. David kneels over Steve’s prone body and, bares his belly, but we can’t see what he’s doing. He straightens up, and announces, “I made the incision.” Keeping his sterile hands up in the air, he says, “Now I will giggle the colon.” Nancy, always the ready accomplice, stuffs a tangled mass of wires under Steve’s shirt. With his invisibly gloved hands, David carefully pulls the wires out, saying, “Here comes the disease.” Steve covers his face with one arm, perhaps to keep from laughing. David then goes to “operate” on Barbara.

Meanwhile Trisha is rearranging the patients—with emergency-room haste. She puts Steve’s arm on his chest, bends Barbara’s knee, swats Steve’s arm back to the floor, shoves Barbara’s arm to one side. She pulls Nancy down, so Trisha now has three patients, but the way she’s racing around, it seems like a whole hospital full of injured people. The audience is laughing continuously during her mad, zigzagging dash. She’s racing against time, while she manipulates their limbs again and again, to a ridiculous sound track of a hyper-fast waltz accented by the sound of a cuckoo. It’s task dance on speed, a crazed nurse choreographing her patients—or a patient herself, fulfilling some mad compulsion.

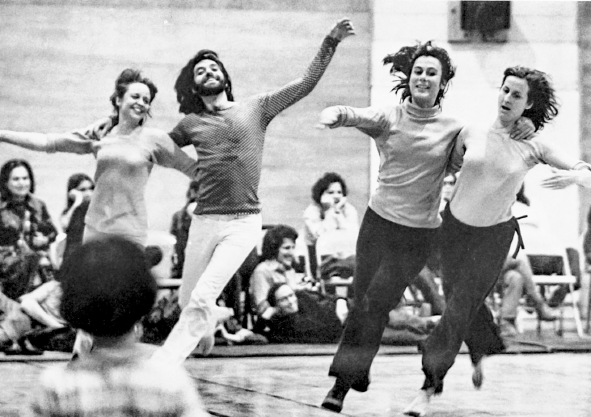

LOGIUDICE GALLERY, MAY 1972

Barbara, wearing a red flowered skirt, stands on top of a chair, her back to her fellow dancers. She slowly gyrates her pelvis as though hula dancing. Sweetly provocative, it’s a languid, lilting accompaniment to the Rolling Stones’s “No Expectations.” The song has a plaintive, sensuous quality, and the lyrics hint at indulging in the moment: “Take me to the station and put me on a train, I’ve got no expectations to pass through here again. Once I was a rich man, now I am so poor. But never in my sweet short life have I felt like this before.” This is Barbara’s meditative streak gone seductive.

Trisha and David decide on a plan. They pick up each dancer, one at a time, and transport that person to another spot. They have already done this with Yvonne and Douglas, and now they come for Barbara. Still standing on the chair, she is now arching way back—gorgeously precarious. They lift her together with the chair, and she keeps arching, a dangerously weeping willow. When they set her down, she resumes her hip swiveling with eyes closed.