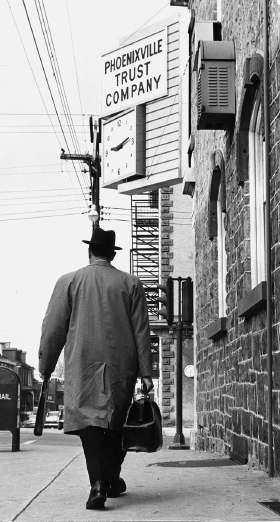

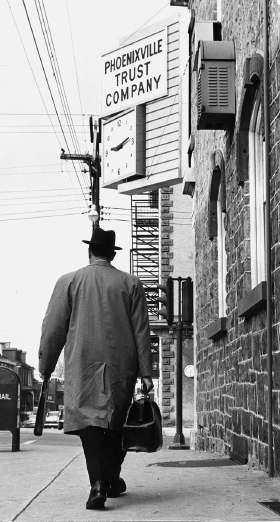

Figure I.1 The Burroughs Corporation salesman shown in this photo carried a bag and helped keep installations of Burroughs equipment running in the mid to late 1950s. Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota.

The computer services industry—which includes consulting services, programming services, systems integration, management of data centers, and time sharing (a forerunner of cloud computing)—is one of the most important industries, and historically one of the least understood. The industry, which in 2014 had worldwide annual revenue of $954.8 billion and which employs millions of people, played a critical role in ushering in the information technology revolution of the second half of the twentieth century.1 It now is helping to define and redefine IT (and the global economy). Despite its size, it has received far less attention—from scholars or from journalists or other writers—than the computer hardware industry or the software products industry.

The true importance of the computer services industry lies not in its impressive revenue, but in what it has accomplished in shaping the information technology landscape. Since shortly after the advent of digital computing, this industry has been fundamental to the organizational adoption of computers, and to making these machines and systems useful. It has long provided customized solutions for the IT wants and needs of customer organizations.

This book is at the intersection of the history of technology and business history. It seeks to understand information technology services within their larger technological systems consisting of (but not limited to) tools of the trade (computers, operating systems, networking, programming languages, and tacit knowledge), labor, sites of production, and various types of intermediate and end-user organizational customers. What this industry produces varies greatly in form and function, from the IBM customer engineer who “carries a bag” and keeps mainframes up and running to the systems analyst designing a new business application and overseeing a team of programmers writing code—the ethereal “ghost in the machine,” that like the product of poets, is “created by the exertion of the imagination” and “only slightly removed from pure thought stuff.”2

Figure I.1 The Burroughs Corporation salesman shown in this photo carried a bag and helped keep installations of Burroughs equipment running in the mid to late 1950s. Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota.

There is also great variance of scale and scope of computer services, ranging from an independent contractor doing network administration services for the staff of a small church or a consultant advising on simulation software tools for an energy exploration client to hundreds of programmers, analysts, and managers engaged in developing and deploying a real-time airline reservation system, or the efforts of an even larger systems integration team to create and refine a billion-dollar system of networked computers and software to manage logistics for the US Air Force in real time. With regard to business history, the book seeks to contribute to what historian Kenneth Lipartito recently has characterized as the “new business and economic history,” in which the “material” and the “mental” are simultaneously examined to understand the past.3 Using such an approach, I examine trade patterns, globalization, organizational structures, value chains, managerial philosophies, financial and business strategies, professional organizations, political economy, mergers and acquisitions, regulation, anti-trust lawsuits, and lobbying. At the same time, I also consider discourses, imagery, icons, language, memes, and metaphors—gender representation, gendered language and spaces, corporate cultures, notions about expertise, marketing of “solutions,” and visualizing clouds.

Design and development of electronic digital computers in the United States first occurred during World War II, and commercial systems were on the market by the early 1950s. In the computer industry’s first decade, most scientific and defense-oriented programming was done internally, by personnel within the organizations that had acquired digital computers. Scientists and engineers in government laboratories and defense-related organizations largely taught themselves and their colleagues to program, either in machine code or with programming tools (compilers) that translated more accessible notation into machine code. As systems grew increasingly complex, especially with the advent of early computer networking, the emerging computer services industry provided critical systems integration work.

Meanwhile, outside of the big science/defense sector, the computer services industry was fundamental to the origin (in the mid 1950s) and the phenomenal growth of computer-based business data processing. With large-scale systems integration, and particularly business data processing, the computer services industry also played a fundamental and continuous role in circulating IT knowledge, reducing the disadvantages to organizations with less internal IT infrastructure and uplifting the overall performance of information technology.

Client organizations and the trade and popular presses often have been critical of computer services companies and the broader industry, especially for real and perceived failures on specific, large-scale, high-profile government projects. Early problems with the roll-out and use of Healthcare.gov (the Web-based platform often referred to as “Obamacare”)—an effort that cost hundreds of millions of dollars and involved sixty IT services firms—represents only one of the more recent debacles (real or perceived) of large-scale systems integration services.4 For contracting specialists and project managers at client firms and government departments and agencies, the presence of failures, delays, and cost overruns by their computer services contractors have at times seemed to be more the rule than the exception. These problems, however, have been at least as prevalent on comparable internal IT projects and speak more to the technical and managerial challenges of designing, developing, integrating, and maintaining software and systems than the computer services industry’s underperformance or lack of expertise. Although large efforts in programming and systems integration always introduce major technical and organizational challenges, even small programming projects can be difficult. Some of the problems stem from the complexity of programming, others from difficulties with the identification and clear communication of the needed business attributes and functionality for systems to technically oriented programmers, and still others from clients’ changing specifications in the middle of a project.5 Since the earliest days of computer programming, specialists and the trade press have often referred to programming as a “black art.”6 Despite decades of efforts at software engineering, programming remains largely a craft enterprise that requires significant creativity and is deeply resistant to efforts to impose factory practices in order to scale up. Quite simply, creating software is hard and managing large-scale programming and systems integration is much harder.

Throughout the history of the computer services industry, the boundaries of the industry have been varied, rapidly changing, and difficult to define. The industry’s complexity, rapid evolution, and sometimes stealthy nature (from classified military projects and corporate client preferences for inconspicuous services contractors to the industry’s narrow marketing efforts relative to the computer hardware and software products trades) have contributed to its being largely ignored by historians and other scholars. The absence of high-quality sources of material on the history of the industry has also been problematic.

Martin Campbell-Kelly has published the most significant piece of scholarship on the early years of the computer services industry, a chapter in his book From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry.7 In that highly insightful book, Campbell-Kelly focuses on the history of the software products industry, not on computer services. In detailing the history of software products, Campbell-Kelly rarely discusses the services industry beyond its first decade, or outside of two chapters. His chapter on the early days of the computer services industry essentially serves as a pre-history to software products; as he notes, some of the early services firms attempted to reap scale benefits by selling identical code (products) to multiple customers.8 There are also several articles on the history of the industry, and a few internally produced company histories, but the literature is sparse compared to the computer services industry’s longstanding technical, economic, social, and cultural importance.9

Though the scale benefits of selling products proved attractive, the services industry certainly did not diminish with the advent of software products. The software products industry emerged in the early 1960s, less than a decade after the start of the computer services trade, and the two industries have grown rapidly side by side ever since. The need for customized solutions, not just standardized products, remained paramount for many customers, and the computer services industry has always been the larger of the two industries—despite far greater public recognition of software products, especially in the era of the personal computer.

For decades, individuals have been customers of software products, whereas the computer services industry has long targeted primarily organizational customers and clients.10 The emergence of one clear software products leader in the personal computer era (in revenue and as a provider of the most common applications and operating systems), Microsoft, has contributed to the high profile of products relative to services. Journalists have created a cottage industry writing books and articles about Microsoft and its co-founder, Bill Gates (now the wealthiest person in the world, with a net worth of approximately $75 billion).11 Though Microsoft is targeting services as never before under its new CEO Satya Narayana Nadella’s push to cloud computing, it is still widely perceived to be (and to a large extent it still is) principally a software products company. The only widely recognized public figure from the computer services industry, H. Ross Perot, is known far more for his battle with General Motors’ then Chairman and CEO Roger Smith, for orchestrating a rescue of two of his employees from Iran in 1979, and for his 1992 campaign for the presidency of the US than as the visionary founder and longtime leader of Electronic Data Systems (EDS).12

The boundaries of the computer services industry, as an agent of and a respondent to our rapidly changing IT world and its surrounding institutions, practices, and people, have been continuously in flux. It is an enigmatic industry, characterized by diversity and dynamism, that sometimes defies clear definition. In addition to its seemingly amorphous nature, the lack of strong primary sources has long posed major challenges to the historical study of this industry. These have been among the reasons why the scholarly community (and other writers) have overlooked this fundamentally important industry for many years.

This book was made possible by newly available archival resources (particularly at the Charles Babbage Institute), by tapping long existing records in new ways (especially from the IBM Corporate Archives), and by oral history interviews and extensive mining of trade literature.13

A few major computer services corporations have been in operation for more than 40 years; among them are Automatic Data Processing, Computer Sciences Corporation, and International Business Machines. Big Eight accounting firms (including Arthur Andersen and Price Waterhouse) and management consulting firms (such as McKinsey and Company, and Deloitte, Haskins, and Sells, now known as Deloitte Touche) also have participated, to varying degrees, in this industry. In recent decades, large corporations long known for their leadership in computer hardware—IBM, Hewlett-Packard (HP), Fujitsu, and Xerox—have focused heavily on computer services as a primary profit center. IBM is currently the worldwide revenue leader of the computer services industry; and since its acquisition of EDS in 2008, HP has been second. Despite the presence of giants, many small enterprises—independent contractor brokerages, specialized consultancies, and self-employed individual contractors—have contributed mightily to this industry.

In short, the computer services industry (which recently has also been identified as “IT services”) has been fundamental to making computers, software, networking, and overall IT systems work (that is, operate reliably, securely, and efficiently). It also has been important to the circulation of knowledge and best practices in IT, to the identification of new applications for computers, and to creating IT work (in the sense of extending the growth of the international IT labor force).

For many years the industry was largely national, and some segments and firms operated primarily or even exclusively in particular metropolitan areas or regions. The industry originated in the United States (easily the largest computer market throughout the second half of the twentieth century and beyond), and the US is still by far the global leader in computer services. The largest US computer services firms—IBM, HP, Accenture, and Computer Sciences Corporation—now have substantial facilities and presence overseas, and compete with international corporations such as Japan-based Fujitsu, France-based Cap Gemini, and India-based Tata Consultancy, Infosys, and Wipro. The Indian computer services industry has grown more rapidly in the past 15 years than its American or European counterparts, and Tata Consultancy has broken into the global top ten in IT services industry revenue. With all of the largest computer services companies operating on an international basis, the location of origin, or the corporate headquarters, has become less significant over time. Cognizant (based in Teaneck, New Jersey) is often listed with the Indian giants, since the vast majority of its staff of over 200,000 is based in India. Yet alongside the industry’s globalization and the rise of large multinational companies, many thousands of small computer services firms continue to operate exclusively within a 50-mile radius.14

In the early to mid 1950s, when pioneering firms launched computer services, they focused on distinct types of services. Martin Campbell-Kelly concentrates heavily on Computer Usage Corporation (CUC) and on C-E-I-R, both of which were programming services enterprises, in characterizing the launch and early history of the computer services industry. (CUC formed in 1955 and C-E-I-R entered the computer services market in 1956.) Although these firms were important, and although the programming services segment has long been one of the industry’s most important segments, computer services really originated in two other segments: consulting services and data processing (service bureaus). Both of those segments began in 1953 (service bureaus have a much older pre-computer history), two years before the programming services segment. Prior to contracting with providers of programming services, client companies and organizations had to decide to acquire mainframe digital computers and to decide what mainframe system to buy or lease. Some took their cues strictly from the mainframe firms—especially if they had been longtime customers of the computer provider for pre-computer punch card tabulation machinery (as many had been with IBM or Remington Rand). Many companies and organizations, however, wanted independent expertise on making the important decision whether to invest in entering the computer age, the timing for this move, what computer system to acquire, whether to buy or to lease, what applications to focus on, and what programming to do in house and what programming to outsource; they also wanted detailed cost–benefit analyses of different possibilities. Consulting firms also provided thorough studies of competitors in individual industries to help firms understand threats and opportunities for IT in their particular trade. In 1953 and 1954, several businesses—among them the accounting firm Arthur Andersen and Company and startup companies John Diebold and Associates and Canning, Sisson, and Associates—launched the computer services industry by providing IT consulting services. In this book, by providing case histories of those three firms, I show how they provided customers with the know-how they needed in order to use digital computers effectively.

With the advent of computer networking, systems became increasing complex. Firms emerged to help organizations (primarily departments and agencies of the federal government) integrate systems by bringing hardware, software, and networking together to create effective and efficient systems. System Development, founded in 1956, was the first systems integration firm.

For companies and for organizations, outsourcing computer-based data processing became an alternative to acquiring digital computers, greatly reducing upfront costs. Data processing using pre-computer punch card tabulation dated back to the late nineteenth century, and often services were bundled with purchases or rentals of tabulation machines. In 1932, IBM formally launched fee-based punch card data processing services by selling time on tabulation machines and expertise from IBM machine operators through its newly formed service bureaus in major cities around the world. IBM’s first computer-based service bureau was launched in 1953.15

Whereas IBM provided a broad array of data processing services, specialty data processing providers emerged after World War II. Of these specialized data processing providers, none became more significant than Automatic Payrolls, Inc., founded in 1949. In the late 1950s, the firm—still specializing in the involved, regular, and mundane task of preparing payrolls for clients—switched to incorporate first punch card tabulation equipment and then (at the start of the 1960s) digital computing technology and had changed its name to Automatic Data Processing (ADP). Consulting services, programming services, systems integration, and data processing outsourcing (or sale of machine/system time) characterized the formative years of the computer services industry—the focus of part I of this book.

Throughout the book, I use case studies of individual firms to introduce particular segments of the computer services industry, highlighting the visionary leaders who launched different areas of the industry and in the process forever transformed computing and software. In addition to the case studies, I discuss other firms briefly to provide further context. The companies (cases) were chosen both for their prominence and as representative examples of currents in the broader industry.

Early on, virtually all computer services firms specialized in a particular segment: consulting, programming services, systems integration, or business data processing/service bureau operations. These first four segments originated in the 1950s. Two additional segments, facilities management and time sharing, emerged by the mid 1960s. To a certain degree, time sharing (as a services business) was merely an innovative way of extending the functions of service bureaus to take advantage of computer networking and the sharing of resources across different geographies (computer processing no longer needed to be in the same location as the computer user). It also fostered more direct interaction with systems by clients than in batch processing environments.

The requisite knowledge, skills, practices, marketing, and contracting strategies differed significantly among these various segments of the computer services industry. Eventually, most of the large-scale computer services companies invested in developing the resources and organizational capabilities to provide a range of different types of computer services, gradually adding additional industry segments to their repertoire of businesses.16 For instance, within five years of its formation in 1959, the programming services specialist Computer Sciences Corporation developed a highly successful systems integration business focusing heavily on government clients.

The book concentrates mostly on developments in the United States and on firms based there. In large part, this reflects the industry. Three of the today’s four global leaders among IT services companies (IBM, HP Enterprise, and Accenture) are based in the US; Japan-based Fujitsu rounds out the top four. All four of these firms have personnel and offices spanning much of the world. In the more distant past, all of the industry’s top ten companies were based in the US. Though the book unquestionably has a US focus (and is in part a product of resources available in archives located in the US), I also explore the overseas expansion of US-based industry giants (IBM, Andersen/Accenture, Control Data, Tymshare, and others). Of equal significance, I analyze the history of the IT services powerhouses Fujitsu (based in Japan), Cap Gemini (based in France), and India’s Big Five (Tata Consultancy, Wipro, Infosys, HCL Technologies, and Cognizant) to provide further international perspective on this global industry.

Chapter 1 concentrates on Arthur Andersen and Company, John Diebold and Associates, and Canning, Sisson, and Associates, and on the industry segment of computer consulting services that those firms pioneered. Arthur Andersen and Company was a large accounting firm that, like several of its competitors, also engaged in management consulting. It probably was the first company in the world to contract to provide computer consulting services. In 1953 it was hired by General Electric to provide advisory services on computer-based payroll and inventory management systems for GE’s pioneering Appliance Park facility in Louisville. John Diebold and Associates and Canning, Sisson, and Associates, both launched in 1954, may well have been the two earliest startup computer consulting firms.17 All three of the case studies in chapter 1 concentrate on how computer services companies constructed and conveyed expertise at a time when computer-based business data processing was entirely new. These case studies also introduce the fundamental role of computer consulting companies, and later of all computer services firms, in circulating knowledge and best practices among clients.

Although many larger corporations had acquired computers by the late 1950s, others had not. Some found it more efficient to rent computer time or to outsource data processing. Computer-based service bureaus that sold computer time and provided certain other computer data processing services emerged in 1953 with IBM’s Technical Service Bureau, which later became part of IBM’s Service Bureau Division. In 1956, as part of an IBM settlement of a US Justice Department anti-trust lawsuit, IBM transformed the Technical Service Bureau into the Service Bureau Corporation (SBC), a wholly owned subsidiary. All of the service bureaus of the 1960s maintained, or brokered the use of, mainframe systems and sold computer time; some of them also offered associated programming and data processing services (processing the bureaus would do for the client). Chapter 2 details the activities and the growth of computer-based service bureaus (including their pre-history in punch card tabulation bureaus) and of data processing specialists such as Automatic Data Processing (ADP).

Chapter 3 analyzes three of the earliest programming services companies: Computer Usage Corporation (CUC), C-E-I-R, Inc., and Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC). In 1955, Computer Usage and C-E-I-R pioneered programming services, which allowed customers to make use of their new digital mainframe computers to advance their enterprises. One important element of success in programming services was recruiting and retaining talented programmers and systems analysts. Programmers could vary widely in productivity, and often there were shortages of quality programmers. Many in the industry and trade presses spoke of a “software crisis,” in which software and its creators were the bottleneck to getting the most from computing systems. The case study of C-E-I-R in chapter 3 benefits from the Charles Babbage Institute’s archive of the firm’s records. CSC began nearly five years later than CUC and C-E-I-R, but thanks to important early contracts it grew faster than these companies. Chapter 3 also introduces the topic of gender in the industry.

IBM was the primary computer hardware contractor for the Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) radar and computerized air defense system in the mid 1950s, and was solicited by the Air Force to take on SAGE programming and systems integration work. Ultimately, IBM’s leaders declined the opportunity to take the lead in this new and highly challenging programming and systems integration task, and the Air Force turned to nonprofit research corporation, RAND, for a solution. In the mid 1950s, the RAND Corporation established System Development Division—soon spun off and renamed System Development Corporation (SDC)—to do the complicated programming, debugging, and systems integration work on SAGE. By the late 1950s, SDC had more programmers and systems analysts on staff (over 500) than any other organization in the world, and the company grew larger than its parent, RAND. There was high turnover at SDC, and over the succeeding ten years former SDC employees helped to populate the computer industry, the computer services industry, and the emerging software products industry.

Informatics, a for-profit corporation founded in 1962, provides a contrast to the (initially) nonprofit SDC. For a number of years the federal government was the primary source of contracts for systems integration, but soon more and more large corporations (among them airlines seeking real-time reservation systems) became important clients. Most of the major mainframe computer firms launched divisions to serve the federal government on systems integration projects by the 1960s—though this services work, from a revenue standpoint, was sometimes invisible as it was bundled in with the cost of hardware. Chapter 4 focuses on the histories of SDC and Informatics.

The computer services industry originated with consulting services, soon followed by the data processing, programming services, and systems integration segments. Part II of this book explores the emergence and evolution of the computer services industry’s identity in the 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s.

Unfortunately, relatively few scholars have followed business historian Louis Galambos in analyzing trade organizations.18 In considering the computer, software, and services industries, scholars have conducted in-depth studies of professional organizations (including the Data Processing Management Association) and software user groups (including SHARE, Inc.), but have paid far less attention to trade organizations.19 An exception is Larry Browning and Judy Shetler’s valuable study of a prominent semiconductor trade association, Sematech, but there is nothing comparable in computing, software, or services.20 Not only do trade associations help competitors cooperate to advance an industry (and segments within it); they help define an industry’s identity. This was certainly true with the Association of Data Processing Services Organizations (ADAPSO),21 launched in 1961 by service bureau companies to represent and advance the interests of their industry.22 ADAPSO quickly broadened to serve other types of computer services businesses, and in time to serve software products enterprises as well. ADAPSO’s history and the emerging identity of the computer services industry in the early 1960s are the topics of chapter 5, which benefits greatly from use of ADAPSO’s organizational records in the archives of the Charles Babbage Institute.

Chapter 6 and 7 focus on two new segments of the computer services industry that originated in the 1960s: facilities management and time sharing. Both of those segments sought to advance efficiencies in computing and data processing, but they had different origins and paths. Facilities management, as with all computer services, required technical skill, but primarily was an organizational invention (outsourcing that combined programming services, data processing services, and maintenance services) to improve efficiency. In contrast, computer time sharing consisted in part of technical advances in networking and operating systems to aid efficiency, enhance the user experience, and make computing more economically and geographically accessible.

H. Ross Perot, the founder of Electronic Data Systems, astutely recognized that many firms that had been early adopters of digital computers had peaks and troughs in workload (processing time and labor) in their data processing departments. Some of these organizations had gotten in over their heads in rapidly transitioning from pre-computer data processing to computer-based data processing. Perot and EDS established a business model of contracting to completely take over an organization’s IT facilities on a fixed-price basis, and utilized downtime for workload and computer processing resources (excess capacity) at one client to serve other clients.

In the early 1960s, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology invented time sharing, later reinvented at other institutions and then modified and commercialized by General Electric, Tymshare, and other for-profit corporations.23 Time sharing rapidly rotated (at split-second intervals) the processing resources of mainframe computers among many users (at basic terminals or smaller computers) to give users the experience of having their own mainframe.24 In its early years it operated through either local networking or telecommunications-based remote networking. In the late 1960s several time-sharing enterprises built computer networks connecting facilities within many cities throughout the nation. For a number of years, Tymshare was second only to General Electric (GE) in the computer time-sharing industry—both of which built sizable computer networks. Some computer services providers that focused on other business areas quickly added time-sharing and facilities-management businesses. Time sharing was a major force in bringing computing resources to new customers and to new regions of the nation and the world, and was a partial realization of efforts to make computing a broad-based, accessible “utility.”

To varying degrees, the mainframe firms of the 1960s provided computer services to their customers. In some cases it was bundled as part of the package to hardware customers; in others it was established as a distinct business division. While IBM was by far the largest computer producer, controlling 60 percent or more of the industry from the late 1950s through the 1970s, it also engaged in major services efforts, such as the programming and systems integration of the Semi-Automatic Business Research Environment (SABRE)—a project completed in partnership with its customer American Airlines. IBM also provided its hardware customers with extensive educational services. IBM Customer Engineers (CEs) kept machines operable with hardware maintenance and debugging assistance. Beginning in 1960, IBM System Engineers (SEs) provided clients with systems analysis consultation. Further, IBM’s Federal Systems Division provided extensive computer services to the federal government throughout the 1960s, the 1970s, and the 1980s.

IBM, as the largest mainframe producer, had far more services personnel than any competitor in the computer industry. In terms of the proportion of services revenue to overall revenue, however, no mainframe manufacturer was more deeply involved in selling computer services before 1990 than Control Data Corporation (CDC). Although CDC historical literature focuses heavily on the company as the supercomputer industry leader, by 1964, when its first supercomputer (the CDC 6600) hit the market, CDC was firmly committed to growing its already considerable computer services business. It did this both through internal expansion and through acquisitions—it acquired the programming services pioneer C-E-I-R in 1967 and (from IBM) the Service Bureau Corporation in 1973. Chapter 8 documents IBM’s pre-1970s work in the services field and CDC’s transition to become primarily a services company. The analyses of the services work and services businesses of these two firms were made possible by resources in the IBM Corporate Archives (at IBM) and the Control Data Corporation Records (housed at the Charles Babbage Institute).

By the late 1960s the computer services industry consisted of a number of large corporations—including IBM, CSC, EDS, and CDC—but the industry has always had many small enterprises (including many businesses serving only one local metropolitan area). Some of these small firms competed with the large corporations for contracts, but more often they focused on providing computer services to small to mid-size companies, local governments, and nonprofit organizations. Without these smaller providers of computer services, many enterprises would not have been able to effectively and efficiently adopt computing technology for their data processing needs. Some clients relied on self-employed independent contractors for computer programming. Many independent contractors, however, lacked either the ability or the desire to network and to successfully market themselves to potential clients. In addition, marketing could be time consuming and expensive for individual contractors, reducing billable hours. Clients often needed multiple contractors for programming projects, and there was much administrative effort and worrisome risk with hiring numerous independent contractors. Meanwhile, traditional computer services companies, in keeping salaried employees on staff (“on the bench”) when they were not out servicing clients, created inefficiencies. In 1972, seeing all this, Grace Gentry established a new segment of the computer services industry: independent contractor brokerages. Her company—Gentry, Inc.—pioneered the industry segment of firms brokering relationships between independent contractors and customer organizations/clients. Carefully screening and assessing the skills of experienced programmers and systems analyst contractors, Gentry placed qualified contractors in client firms, taking a modest percentage of what the client paid for each person-hour of work.

Chapter 9 analyzes Gentry, Inc., and two other early independent contractor brokerages: Phyllis Murphy and Associates and COMSYS. These companies worked with between 50 and 200 contractors at a time, placing them in both short-term and long-term projects with clients. The chapter also explores the trade association for this industry segment, the National Association of Computer Consultant Businesses. The NACCB—launched solely to combat changes successfully lobbied into federal tax code by ADAPSO, whose members consisted of larger services companies that wanted to reduce or eliminate competition from independent contractors and brokerages—quickly evolved into a broad-based trade association for independent contractor brokerages. The chapter also analyzes gender in the computer and computer services industries. Grace Gentry, Phyllis Murphy, and other female entrepreneurs had faced substantial barriers to advancement while working for large organizations in computing and data processing earlier in their careers; becoming entrepreneurs, their own boss, was a way to potentially move past that. The chapter was made possible by oral histories and by NACCB records provided to me by Grace Gentry.

Since the late 1980s, computer services companies and the broader industry have gone through fundamental organizational and geographic changes. Chapter 10 focuses on those changes, surveying three themes—transforming giants (IBM, HP, Fujitsu, Capgemini, and Andersen/Accenture), offshoring enterprises and labor (India’s Big Five IT services providers and US-based IT services companies changing geographical deployment of their workforces), and cloud services—over the past 35 years. Cloud computing, a mid-1990s re-invention and reformulation of time sharing, is a dynamic, paradigm-changing, fast-growing phenomenon that has attracted startup companies seeking to define the field for particular applications such as Salesforce.com (in customer relationship management software), existing IT services giants (IBM, HP, Fujitsu, Capgemini, CSC, and India’s Big Five), and large firms from other areas of IT (among them the e-commerce powerhouse Amazon and software products leader Microsoft). With such a cast of providers, cloud computing’s momentum is strong and the IT services industry is evolving rapidly.

The case-focused approach of this book provides a look into the tremendous diversity of the computer services industry over the past six decades and the evolving strategies of many firms. The book’s structure also facilitates analysis of a number of core themes. First and foremost is the role of the computer services industry in shaping information technology and making IT work over the past 60 years (creating applications for computers that operate effectively). Second, the industry has become a strong contributor to the US economy and making IT work (in terms of national and international jobs creation—the global computer services industry labor force is composed of millions of workers). The falling price for processing power and memory (Moore’s Law), coupled with the growth of computer networking knowhow and infrastructure, has enabled considerable offshoring of some types of computer services work (particularly to India—both to US multinationals overseas as well as to overseas-based firms), while other services work is strongly tied to place (either by necessity or preference/opportunity). Third, the computer services industry has long had a fundamental role in the circulation of IT knowledge and skill. This has helped to level the IT playing field, partially offsetting disadvantages faced by organizations with less internal IT infrastructure. Fourth, the computer services industry has played a major role in boosting efficiency and flexibility. It allows firms to outsource IT work to true specialists for particular types of applications, and to balance the inevitable uneven needs for IT labor and computer processing—cloud computing appears to further advance such economies and efficiencies. Only time will tell whether cloud computing becomes the new dominant IT services model. It is currently approaching 15 percent of overall IT services industry revenue, and is growing much more rapidly than the overall IT services industry.