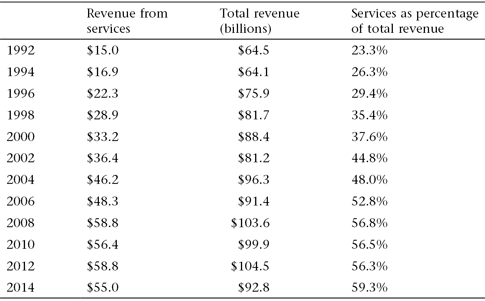

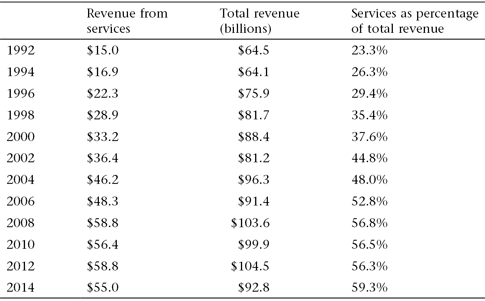

Table 10.3 IBM’s global revenue, 1991–2015.

Source: IBM annual reports, 1991–2014, IBM Corporate Archives.

Historians often are reluctant to write about the recent past, present developments, and future trajectories. The computer services industry underwent massive growth and many dynamic changes in the past several decades—phenomena that cannot be ignored. This chapter surveys the past 35 years through three themes: IT industry giants that underwent major transformations, geographic shifts of IT services enterprises and labor, and the disruptive model of cloud infrastructures and associated services. Future scholars, with more historical distance and with access to a larger store of primary source material, undoubtedly will analyze these issues, and many others, in greater depth.

The market research firm INPUT estimated information technology services industry revenue at $31 million in 1982, with data processing services (table 10.1) and professional/consulting services (table 10.2) the two largest segments.1 By 2014, the industry had grown by a factor of about 30 to reach annual revenue of $955 billion—roughly the same size as the global pharmaceuticals industry.2 As was explored in earlier chapters, the trend from the mid 1950s on was for computer services firms to begin by specializing in one segment (programming services, data processing/data centers, time sharing, consulting, or systems integration) and then gradually broaden to build capabilities and businesses in some or all of the other segments. IBM, Hewlett-Packard (HP), Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC), Control Data Corporation (CDC), Electronic Data Systems (EDS), Arthur Andersen/Andersen Consulting/Accenture, and Sperry-Univac and Burroughs (and their combination as Unisys) all became diversified players in the IT services industry—and IBM, HP, and Accenture, along with Japan-based Fujitsu, are the current leaders in the industry. Automatic Data Processing (ADP) stands as an exception, having long remained specialized as an unparalleled leader in payroll processing—it currently serves companies and other organizations in more than 100 countries and processes the payrolls of 8 percent of the world’s workforce.3

Table 10.1 The top vendors of data processing services by revenue in 1982.

| Rank | Company | Revenue (millions) |

| 1 | Automatic Data Processing, Inc. (ADP) | $599 |

| 2 | Control Data Corporation (CDC) | $590 |

| 3 | General Electric (GEISCO) | $282 |

| 4 | Electronic Data Systems Corporation (EDS) | $256 |

| 5 | Tymshare, Inc. | $178 |

| 6 | McDonnell Douglas Automation (McAuto) | $177 |

| 7 | Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC) | $151 |

Source: INPUT, “US Information Services Markets, 1983–1988: Industry Specific Markets, Volume 1” (1983): 48.

Table 10.2 The top vendors of professional/consulting services in 1982.

| Rank | Company | Revenue (millions) |

| 1 | Computer Sciences Corporation (CSC) | $420 |

| 2 | Electronic Data Systems (EDS) | $250 |

| 3 | Burroughs Corporation | $232 |

| 4 | International Business Machines (IBM) | $195 |

| 5 | Arthur Andersen and Company | $187 |

Source: INPUT, “US Information Services Markets, 1983–1988: Industry Specific Markets, Volume 1” (1983): 58.

In 1982 the top seven firms in data processing services produced $2.2 billion in revenue, while the leading five companies in professional services had revenue (in this area) of about $1.3 billion. Roughly 6,000 other companies, in aggregate, recorded the remaining 83 percent of IT services industry revenue that year—proportions long typical in this highly diffuse industry.4 While the trade continues to grow rapidly, as do its leading firms, it remains an industry of many small and mid-size companies, and only a handful of very large ones. In 2010 the top five global enterprises accounted for less than 20 percent of the industry’s revenue, and many thousands of other companies and independent contractors produced the rest.5 Over the same period, IBM, the leading IT services firm for more than 25 years, generally recorded 6–8 percent of the trade’s annual worldwide revenue. In 2014, IBM’s share of the world market fell to roughly 5.5 percent. (See table 10.3.)

Table 10.3 IBM’s global revenue, 1991–2015.

Source: IBM annual reports, 1991–2014, IBM Corporate Archives.

The year 1982 also marked the end of the US Department of Justice’s lengthy anti-trust case against IBM—it was dismissed as “without merit.”6 The Department of Justice’s lawyers on the case (a group that was perpetually in flux, as heavy workloads and modest government salaries resulted in high turnover) argued that IBM had engaged in subtle anti-competitive practices for many years. The reasons for the abrupt dismissal of the case are not entirely clear, but the Reagan administration, one way or another, wanted to conclude longstanding and costly cases against IBM and AT&T (the AT&T case, which began in 1974, also concluded in 1982, and led to the breakup of the telecommunication conglomerate’s local telephone business into the “Baby Bells”).7 A likely factor in the dismissal of the IBM case was that the computer industry looked far different in 1982 than it had in 1969, when the Department of Justice had filed the case—IBM was less dominant, as a result of the growth of mini-computing (a field in which Digital Equipment Corporation, IBM, and to a lesser degree Hewlett-Packard, Honeywell, Data General, Wang Laboratories, Prime Computer, and others had thrived), and of personal computing (in which IBM had many competitors—its early-1980s leadership with the PC was short-lived).

The dismissal gave IBM’s leaders an unambiguous green light to focus on computer services as a profit center, which it did when its hardware business struggled severely in the second half of the decade. IBM’s transformation propelled it to the forefront of an IT services industry that was undergoing considerable change. Tymshare and GEIS, major specialists in time sharing, would be acquired and then decline as the rapid growth of personal computing sent this segment into a tailspin in the late 1980s and the early 1990s. In 1986, Burroughs and Sperry-Univac, in mutual decline, merged to form Unisys. That combination, continued to provide computer services, as its constituent companies had done, but never thrived. And in 1992, CDC was split apart, its IT services portion, Ceridian, becoming more specialized (in human resources software) and never approaching its earlier glory.

On the other hand, ADP grew steadily as a focused giant, though it was surpassed in overall revenue by a number of diversified IT services companies. And another of the firms that had helped launch the industry, Arthur Andersen (and its Administration Services Division/Andersen Consulting), consistently expanded for many years before its rapid growth in the 1990s, battling the accounting side of the company and becoming a large split-off firm with a new name (in 2001)—Accenture. Another early entrant, CSC, also expanded significantly, especially in its specialty of contracted programming services and systems integration for the federal government. And a major computer hardware industry company, Hewlett-Packard, rapidly developed a sizable IT services business in the 1990s and the 2000s and became (and remains) second to only IBM in revenue in this global industry. Furthermore, in recent years the Japanese computer manufacturer Fujitsu, which first moved aggressively into the services business in the early to mid 1990s (accentuated by the opening of its massive Tatebayashi System Center for outsourcing in 1995), has been among the top four firms in the global IT services industry.8

In the second half of the 1990s, the increasing ubiquity of the World Wide Web transformed the IT services industry, which had previously been more closely tied to place. Around 2005, time sharing had a rebirth, reformulation, and renaming as “the Cloud.” Cloud services—a fast-growing area—has become a focus of software products leader Microsoft, IBM, e-commerce powerhouse Amazon, search leader Google, and CRM platform specialist Salesforce.com. The World Wide Web and ever-increasing bandwidth were critical to facilitating the expansion of the IT services industry in India (both native firms, such as Tata Consultancy, Wipro, Infosys, and HCL Technologies, and multinationals from the US and Europe—IBM, Accenture, CSC, Paris-based Capgemini, Cognizant, and others). These native and multinational giants operating in India took advantage of a strong, well-educated, less expensive, largely English-speaking labor pool.9

The global IT services industry has grown very rapidly over the past decade and half. In 2003 it was a $570 billion industry. By 2011 it had grown to $848 billion, and in 2014 it reached $955 billion.10 Behind the strength of cloud services, it is on pace to soon become one of the world’s few trillion-dollar industries.

The remainder of this chapter concentrates on how IBM reorganized to become primarily a computer services business, on the transformations of IBM’s competitors Hewlett-Packard, Fujitsu, Capgemini, and Andersen/Accenture, on a significant geographical shift of the industry labor to India, and on the rise of “cloud services”—“infrastructure as a service,” “platform as a service,” and “software as a service.”

As I write, in January of 2016, IBM recently reported its fifteenth consecutive quarter of declining revenue. CEO Virginia Rometty took the reins at a challenging time in 2012, and IBM is seeking to concentrate on its “strategic imperatives” of “Cloud, Analytics, Mobile, Social, and Security,” double-digit earnings growth areas with major services components, which now represent 35 percent of IBM’s revenue.11 Rometty’s predecessor as CEO, Samuel Palmisano, clung to revenue and profits from an earlier model consisting of IBM hardware, customized IT services, and software (with services and software tilted meaningfully, but not exclusively, to IBM hardware systems), which continued even as the cloud-based model (data, software, and services on server farms/data centers rather than localized customer sites) was beginning to take off. This was done because large and reliable near-term revenue streams for IBM otherwise would have been sacrificed to the cannibalizing cloud—a tough proposition for a widely held public company battling to hit or beat quarterly revenue and earnings estimates. IBM hardware at customers’ sites remains a focus; as Rometty recently pointed out, these are “critical systems for the world.”12 This current transition is delicate and involves many difficult strategic decisions—IBM’s revenue and reputation rest on both its existing core and new imperatives. IBM faced similar reorganization hurdles to bolster top and bottom line growth in the second half of the 1980s and in the early 1990s. At that time, unlike CDC, IBM survived its existential challenge, avoided being broken apart, and set a course for two decades of relative prosperity (albeit with a degree of complacency in concentrating on existing businesses).

After the announcement of the IBM 701 (in 1952), IBM’s revenue increased every year until 1991, the first year it recorded an annual loss. The $2.86 billion loss in 1991 was followed by a loss of $4.95 billion in 1992 and a loss of $8.10 billion in 1993.13 These losses were largely attributable to restructuring. IBM’s problems, in fact, had begun about ten years earlier. IBM was a huge company built around leasing and selling mainframe computers and midrange systems, and on servicing those machines and the customers’ needs with software products and services. Essentially, IBM’s services were wedded to its hardware.

Though IBM broke with its usual practice in using a small independent business unit and outside suppliers to quickly design, develop, and release the IBM PC (in 1981), it did not protect its operating system adequately, and Compaq (which in 1982 reversed-engineered BIOS, the one IBM proprietary element), Dell, and other manufacturers of PC clones thrived as the 1980s progressed—as did Microsoft, which had supplied the original operating system for the IBM PC and which went on to supply standard operating systems to the personal computer industry.14 IBM’s organization and cost structure (large staff, relatively high salaries, large facilities, and mainframe-oriented marketing operation) was not competitive in the long term for PCs (including ThinkPad laptops), and in 2005 IBM would sell 81 percent of that business for the relatively small sum of $1.25 billion (plus considerations bringing a truer real price closer to $1.75 billion) to the Chinese computer maker Lenovo.15 The personal computer was a disruptive technology that hurt IBM, which continued to cling to mainframe and midrange systems and associated software and services revenue in the 1980s. IBM managed to increase its earnings until 1984, then experienced a minor decrease in 1985 and a major one in 1986—the latter year saw a 27 percent decline from the 1984 high.16 Placing quarterly and annual earnings ahead of disruptive shifts, IBM’s leaders delayed making changes, precipitating a more abrupt and difficult transition several years later.

IBM’s new CEO in 1993—Lou Gerstner, who had fresh experience as CEO of RJR Nabisco—often has been celebrated for orchestrating IBM’s turnaround. Gerstner’s memoir, in which he details his leadership principles and practices in making an “elephant” (IBM) dance, became a classic, joining books by Lee Iacocca and others in presenting how a CEO restored a troubled corporation to glory.17 IBM certainly returned to profitability and growth under Gerstner’s watch, and he deserves considerable credit for his leadership in presiding over the financial turnaround. Some of the strategic repositionings that IBM made, however, already were in place in the years immediately preceding Gerstner’s arrival, having been initiated by Gerstner’s much-maligned predecessor, John Akers, IBM’s CEO from 1985 to 1993. Akers appropriately bears the blame for failing to make difficult changes to reposition the company earlier in his tenure and for his fortunately abandoned “baby blues” strategy of breaking IBM into about thirteen independent business units, each which may have had its own stock.18 Akers’ early adherence to IBM’s policy of “lifetime employment,” whereby attrition and shifts were used but layoffs were generally avoided, made subsequent large-scale layoffs late in his tenure (and under Gerstner) all the more painful. Akers suffered from the burden of history, an entrenched corporate culture, and the legends of Thomas Watson, Thomas Watson Jr., and his other predecessors.

In the late 1980s, with substantial anti-trust concerns behind him, Akers engaged in bold moves with services. First he launched a series of small-scale outsourcing experiments to test strategies and perfect skills. Then, in 1989, IBM contracted to design, build, and manage a “state-of-the-art” data center for Kodak, which was to be located in Rochester. Following a model established by H. Ross Perot (a former IBMer), IBM used excess capacity (computer processing and human resources) to service other clients. Also in 1989, IBM penned a deal to operate all IT services for Hibernia National Bank, and instituted a new business services unit whose purpose was to enable an organization to recover from a disaster (e.g., a fire, a tornado, a hurricane, or a power disruption). These major initiatives in 1989 led to a formalized corporate-wide strategic reorganization in 1991. The cost of the restructuring and the weakening in demand caused by the 1990–1991 recession in the United States (and by longer-lived recessions in the United Kingdom, in Continental Europe, in Japan, and elsewhere) resulted in particularly deep annual losses as IBM made its transition.19

In 1991, Akers and IBM’s board of directors authorized a new “worldwide services strategy” that was intended to make IBM a “world-class services company” by 1994. The strategy included restructuring the Systems Services Division to become the Integrated Systems Solutions Corporation (ISSC), a wholly owned subsidiary for providing programming and systems integration services to customers. That year, the new subsidiary began serving numerous corporations, including Supermarkets General, Commerce Bancshares, and First American National Bank of Nashville. The following year, IBM launched its Consulting Group, with a staff of 1,500, to provide IT consulting services to customers in the US and in 29 other countries. With this, IBM was servicing not only customers of IBM hardware, but also clients using a wide range of systems and software from various vendors. In 1992, the ISSC engaged in a major joint venture in networking services with Sears, Roebuck and Company, and signed an $80 million contract to provide IT services to the state government of California for data processing for its welfare system. That year the ISSC also completed a major deal for data centers for United Technologies and a substantial systems integration project for the Czech Republic. Further, it signed on corporate clients for IT for health care systems and for hotel management, two areas that would become increasingly lucrative “verticals” (user industries having specialized needs and requiring specialized expertise). With its growing global services business, IBM established services subsidiaries in Canada, in the United Kingdom, and in Japan in the early 1990s.20

Services contracts continued to grow in length and size as IBM became the long-term services provider for data center management for credit bureau Equifax (a $650 million deal) and railway company Southern Pacific Company (a ten-year $415 million contract). While IBM’s maintenance services revenue remained roughly constant (between $6 billion and $7 billion) in the first half of the 1990s, its other services businesses (programming services, consulting, data center management, and systems integration) grew rapidly and dwarfed maintenance income by 2000.21

Services as an unpriced support to hardware customers had been at the heart of the company’s strategy since C-T-R’s early tabulation machine days, but the 1989 Kodak data center and others to follow, coupled with the rapid hiring of programmers and consultants (to join the systems engineers, customer engineers, and other staff) soon made IBM principally a computer services company. In 1991, services were one fifth of the business by revenue, with hardware and software products both generating considerably more income. In 1995, IBM officially formed its Global Services Division, which brought in one third of the company’s overall revenue in 1998 and more than 42 percent in 2001.22 In 2002, IBM acquired the Global Management Consulting and Technology Services (GMC&TS) unit of PricewaterhouseCoopers. As IT systems became increasingly critical to businesses, especially in the Web era, technology consulting and management consulting became increasingly intertwined—with finance, logistics and sourcing, simulation and modeling, design, personnel management, knowledge engineering, and many other areas. IBM’s existing consultants took a broad view of IT within larger business strategies, much like that of the PwC GMC&TS unit that IBM acquired. The latter, which cost IBM $3.5 billion in stock and cash, brought 30,000 experienced professionals, almost doubling IBM’s newly formed Business Consulting Group of its Global Services Division (which also consisted of a similarly large Technology Services Group).23 Aided in part by this acquisition, IBM’s services expanded from $33.2 billion in 2000 to more than $60 billion in 2011, going from 38 percent of IBM’s overall revenue to more than 56 percent.24

Success often spawns imitation. Hewlett-Packard’s management took notice as IBM was transitioning to focus on the fast-growing IT services field at the end of the 1980s. In the 1990s, HP sought to engage in a similar major transformation.

Two Electrical Engineering graduates of Stanford University, William Hewlett and David Packard (counseled by Frederick Terman of Stanford’s engineering faculty) formed Hewlett-Packard as an electronics company in Packard’s garage in Palo Alto in 1939. Hewlett-Packard, which first produced oscillators, radar-blocking equipment, and other auditory electronics, moved into scientific calculators and minicomputer development in the mid 1960s. Like most manufacturers of mainframes or minicomputers, Hewlett-Packard offered some bundled computer services, but doing so was not a significant business or a core activity for the firm. In the mid 1980s, Hewlett-Packard began building inkjet and laser printers, which, along with producing proprietary ink and toner cartridges, became a major business for the company.25

In 1997, Hewlett-Packard created a Software and Services Group for what had been, by the firm’s own admission, one of the “least visible” of its business areas. Then, in 2000, it created an IT Services Division to go along with its much larger divisions for Computers and Printers and Imaging. HP’s 2000 annual report states that its IT Services Division had $1 billion in revenue that year and began to step up hiring IT services consultants, adding more than 1,700 that year. Its services business at the time was about 3 percent the size (in revenue) of IBM’s. HP continued to accelerate its organic growth of services through aggressive hiring in the early 2000s, and in 2002 the company disclosed that it had 65,000 services professionals worldwide—a number that had risen considerably that year as a result of HP’s acquisition of Compaq, which had taken over the Digital Equipment Corporation four years earlier.26 HP was offering consulting services, imaging and printing services, various networking services, and other IT services to small, medium-size, and large companies, nonprofit organizations, and various levels of government in the US and overseas. With the massive and rapid expansion of its services workforce, HP achieved $12.3 billion in IT services revenue in 2003 and $15.6 billion in 2005. The pace of transition to include this new business was quite remarkable—a division that generated 2 percent of the overall revenue for the company in 2000 was producing 18 percent of its revenue only five years later.27

In 2002, Carly Fiorina of HP, the first female CEO of an IT giant, orchestrated a controversial $19 billion stock-based acquisition of the personal computer maker Compaq against strong opposition from board member Walter Hewlett, son of the company’s co-founder. HP’s takeover of Compaq was controversial not only because of Walter Hewlett’s opposition, but also because personal computers had become a commodity business with ever-dwindling differentiation, pricing power, and margins. Some insiders opposed to the Compaq acquisition saw services as the more important focus, and although Compaq brought a number of services professionals it primarily was a hardware firm. Timing is everything, and Compaq would not be Hewlett-Packard’s last controversial acquisition. In 2008, HP acquired the beleaguered Electronic Data Systems (EDS).28

GM divested its EDS computer services division in 1995 and it became an independent public corporation again. It was a far different organization than when it was acquired by GM a dozen years earlier. GM’s large and diverse IT needs and guaranteed business to EDS allowed the services business to expand quickly, but there was a clash of cultures between the entrepreneurial, longtime stock-option-incentivized IT services firm and the bureaucratic, slow-moving automobile manufacturer. In 1986 EDS revenues rose to $4.4 billion, with $3.2 billion (more than 72 percent) coming from GM.29 At the end of that year EDS’s charismatic founder Ross Perot was bought out (he was GM’s largest stockholder) and forced off the GM board of directors. Two years later he started a competitor in IT services business called Perot Systems. Perot’s departure was a further, albeit partly symbolic blow (as he was less active in day-to-day management) to EDS’s innovative culture, and left the division to adjust as best it could to the management styles and imperatives of a leading automobile manufacturer. This environment, and overly rapid growth, forced the computer services division to focus on large contracts.

By 1995, when EDS became independent again, it had a data center campus in Plano, Texas (built in 1993) with 37 buildings on 360 acres of land, about 100,000 employees, and ever-increasing pressure to reduce bench time for its large workforce.30 With the guaranteed GM business gone, the company had to be more and more aggressive in bidding on large-scale, riskier contracts. On some of these major contracts it lost substantial sums of money—accurately costing and effectively bidding on major programming and systems integration business remains highly difficult to this day. It also led EDS to focus on Y2K readiness/compliance contracts to keep its large workforce busy. What was a blessing for emerging Indian IT giants (discussed later in this chapter) was a curse for EDS. It had carved out a place on the lower-margin, lower-skill side of the computer services business (for a sizable portion of its employees) at a time when IBM was specializing in higher-margin specialized programming for verticals in finance, healthcare, and other industries. The GM years, followed by US-based Y2K contracts, led to a predominantly US-based EDS workforce at a time when IBM and Andersen Consulting were downsizing in the US and expanding their operations in India and in other countries with lower labor costs. EDS was struggling mightily in 2008, when HP acquired it for $13.9 billion—a price that was a mere 63 percent of trailing year’s sales (0.63 price to sales ratio). Valuations under 100 percent of annual sales (or a less than one price-to-sales ratio) are generally considered quite low valuations (especially in the IT field), and an acquiring firm almost always has to pay a substantial premium to the target firm’s pre-acquisition stock price.31

In 2007, IBM had IT services revenue of $54 billion; EDS was second in the global industry at approximately $22 billion.32 By acquiring EDS, HP (which had $16.1 billion in IT services revenue in 2007) immediately became the clear second in the industry, with an eye on dethroning IBM from the top spot. The EDS workforce had grown to about 140,000 employees at the time of the acquisition. HP had 176,000 employees overall, but it had fewer than EDS on the IT services side. IBM and HP were generating roughly similar operating margins of slightly over 10 percent, which was strong performance at the time for an industry that had long been growing fast but had been characterized by modest margins. EDS’s operating margin was considerably lower—about 6 percent. HP was purchasing a relatively expensive workforce that was heavily US based and had many thousands of employees in a single location—Plano, Texas.33 The major challenge ahead for HP was integrating the two businesses. At this time, IBM and the new HP were facing steadily increasing competition from emerging Indian IT services firms, which were operating with lower costs because a large percentage of their employees were in India.

HP also was having reputational problems resulting from a high-profile boardroom scandal and “bad press” concerning underperforming acquisitions. With the former, in an effort to contain ongoing corporate leaks, chairwoman Patricia Dunn authorized the hiring of outside investigators, who proceeded to spy on other board members, employees, and journalists. She and four others were indicted on felony charges in California for “using false pretenses to obtain confidential information from a public utility, unauthorized access of computer data, identity theft, and conspiracy.”34 Dunn had a recurrence of cancer, and the state dropped the charges against her “in the interest of justice.”35 The news story, in the reputation-based business of IT services (particular for a case involving computer crime), hurt HP. Troubling news remained in the headlines for HP as CEO Mark Hurd, who had replaced a fired Carly Fiorina in 2005, resigned after a scandal concerning Hurd’s alleged sexual harassment of an HP contractor/greeter, former adult film actress and reality television contestant Jodie Fisher. An HP inquiry found that Hurd was not guilty of sexual harassment but had violated “HP’s Standards of Business Conduct”; through mutual agreement with the board of directors, Hurd resigned in August 2010.36 Hewlett-Packard then looked to Margaret (Meg) Whitman, who had successfully led the rapid growth of the auction and electronic payments firm EBay, to get HP back on track. She signed on as HP’s CEO in 2011. However, the company’s financial struggles, and the woes that ensued from its acquisitions of Palm, 3com, Autonomy, and other companies between 2009 and 2012, persisted.

In 2015, Whitman and the board of directors decided to spin off the enterprise business (IT services, software, and networking) from the computer and imaging/printer business. Whitman provides leadership for both—as chair of the board of Hewlett-Packard (computer/printers), where Dion Weisler is now the Chief Executive, and as CEO of Hewlett-Packard Enterprise.37 HP Enterprise has its work cut out for it as it, like IBM, seeks to grow higher-margin businesses in cloud services and analytics. In late May 2016, HP Enterprise announced that it would merge with Computer Sciences Corporation, creating a larger entity to better compete with IBM and Accenture. Less than a year earlier, CSC spun off its lucrative government services businesses to merge with SRA in an independent public company called CSRA.38

This (first) separation/change for HP, to create HP Enterprise and have a fully independent IT services consulting business, was also an issue that had played out with Arthur Andersen’s Administrative Services Division (ASD)—though it was a quite different situation as the separation was from Andersen’s accounting side, not a computer hardware business. Arthur Andersen’s ASD had the advantage of never having been part of a hardware company in which computer services were partially or fully tied to the parent firm’s equipment—as it had been for many years at IBM, Sperry-Univac, Control Data, Burroughs, Honeywell, Hewlett-Packard, and other companies. This was more of a burden for IBM’s competitors than for IBM, thanks to IBM’s share of the market for mainframes (though it became a challenge for IBM in the PC era when it had less dominance in the hardware market and it was trying to grow services as a core profit center).

The structure of Arthur Andersen’s ASD made for less bureaucracy and rigidity with hiring, promotion, and launching and relocating new offices—relative to giant mainframe firms with large facilities, such as IBM. By the 1960s, the ASD’s two largest offices were in Chicago and New York City, but it set up many smaller offices as business developed in various US cities and overseas.

Although twelve years had passed before Andersen had hired its first female consulting employee, Andersen/Accenture became committed to gender diversity. In 1965, the Chicago office hired Susan Butler, a graduate of Purdue University. Butler worked on programming a new IBM System/360 at American National Bank in Chicago and went on to be a manager in the Andersen ASD’s Detroit office and then the first female partner in 1979, and shortly thereafter the first managing partner.39 She paved the way for other female executives at Andersen/Accenture, including Gill Rider (who became Accenture’s Chief Leadership Officer in 2002) and Jane Hemstritch (who was named Accenture’s managing director for the Asia Pacific region in 2004).40 Today about 130,000 of Accenture’s 360,000 employees are women, and there is a corporate goal of going from 36 percent to 40 percent by 2017.41

By the early 2000s, Andersen/Accenture was very much an international operation. Andersen’s ASD expanded aggressively in Europe in the 1970s, setting up its international umbrella organization called Arthur Andersen and Company Société Coopérative in Geneva in the mid 1970s. Later, Geneva would become Andersen/Accenture’s headquarters. During the 1970s and the 1980s it expanded its offices in Paris, London, and other major European cities. With growth overseas and in the US, Andersen had about 10,000 IT consultants by 1987.42

Arthur Andersen’s ASD grew faster than the accounting business in the 1980s and in subsequent years, in parallel with and contributing to the rapid growth of the IT services industry. In 1989 the ASD changed its name to Andersen Consulting to better reflect its activities and to help with branding. By the mid 1990s it made up the larger share of the firm’s earnings, and on a per-person basis it contributed far more to revenue and earnings. Many of those in Andersen Consulting resented the level of transfer payments to the parent company. The ongoing conflict played out frequently in the press. Andersen Consulting’s dynamic and successful CEO George Shaheen led the effort for independence. In 2000 an arbitrator ruling led to formally splitting the two enterprises. Andersen Consulting, in 2001, changed its name to Accenture to further distance itself—with a name combining “accent” or “accentuate” and “future.” This change proved fortunate, as the Arthur Andersen name soon was tarnished as a result of the revelation that it had shredded documents (and, allegedly, had earlier been complicit and/or negligent) in the Enron scandal, in which accounting fraud had led to the energy services company’s bankruptcy and dissolution.

The Enron debacle precipitated the end of Arthur Andersen’s accounting business; it relinquished its license to practice public accounting and auditing in 2002.43 That same year, Accenture moved its headquarters from Switzerland to Bermuda. In 2009, it moved its headquarters to Dublin. Its longstanding international focus is serving it well in the global IT services industry. Though all major IT services companies now have a substantial presence in India, Accenture moved quickly to expand its business there. It also has a substantial workforce in the Philippines. Having a substantially lower cost of labor due to its substantial work force in lower cost countries—India and the Philippines—has helped it consistently grow revenue, while achieving roughly 10 percent growth. This is a feat exceeded only by some of the leading India-based IT services giants that have benefited from the massive increase in the outsourcing or offshoring of IT services to India by the US, European countries, and developed Asian countries, and from the lower cost of labor in India relative to the US and Europe.44

Before considering the phenomenal growth of IT services in India, we should take note of two other IT services giants outside the US that are important to understanding the makeup and the dynamics of the global computer services industry over the past several decades: Capgemini and Fujitsu. Capgemini—founded by French entrepreneur Serge Kampf—has similarities to EDS and CSC as a startup services specialist that steadily increased the scale and the scope of its services businesses for years before rapidly expanding in the past two decades. Fujitsu has more in common with IBM and HP than Capgemini has—it is a highly successful vertically integrated computer manufacturer that long provided services, but increasingly it made this one its core businesses (moved from bundling services to hardware, in favor of separately pricing services).

Serge Kampf, born in Grenoble in 1934, received degrees in economics and law before joining the General Direction of Telecommunications in Paris in 1960. Soon thereafter he moved into the computer industry, taking a position with Compagnie des Machines Bull, a firm that had been founded in 1931 to manufacturer punch card tabulation machines and had then (like Remington Rand and IBM) made a transition into computers in the early post–World War II era.45 In 1967, Kampf left Bull and founded a computer services firm called Sogeti SA (convincing three of his Bull colleagues to join him).

Sogeti’s originally location was a two-bedroom apartment in Grenoble that Kampf converted to an office. By the end of its first year, with Kampf as president, the firm had 27 employees, primarily engaged in advisory and programming services, and had made 1.5 million francs. In 1969 it had 49 employees and earned 4.2 million francs (worth about $815,000 in 1969). By that time it had set up a Swiss subsidiary and an office in Lyon. By 1972 it had offices in a dozen cities in France and elsewhere in Europe.46

In 1973, Kampf successfully led Sogeti’s hostile takeover of the French computer services company CAP. In 1974, it acquired the New York–based computer services firm Gemini Computer Systems. The company was renamed Capgemini Sogeti in 1975, and shortened its name to Capgemini in 1996. With the merging of these three firms, Capgemini Sogeti became the leading French IT services enterprise, with roughly 2,000 employees and with sales exceeding 180 million francs in 1975. It provided consulting services, programming services, facilities management, and systems integration to a wide range of industrial and government organizations in France and throughout Europe.47

In the early to mid 1980s, Capgemini Sogeti made its first major expansion in the largest IT services market, the United States, by acquiring firms that it grouped into Capgemini Inc. in 1986. In the previous year it had boosted its resources for both internal expansion and further acquisitions by going public—with its stock being listed on the Paris Exchange. Back in 1982 it had crossed annual revenue of 1 billion francs and less than a decade later, in 1990, it grew 9-fold to exceed annual revenue of 9 billion francs. By the latter year it had 16,500 employees, aided by its 1990 acquisition of the Hoskyns Group (a prominent IT services firm in the UK) for approximately 2 billion francs.48

The many European acquisitions Capgemini Sogeti made in the 1970s and the 1980s gave it a large presence on the Continent (where collectively it held 7 percent of the market), but its market share in the US was only about 1 percent at the start of the 1990s. To provide funds to enable more rapid expansion in North America and elsewhere, Kampf and his board agreed to sell 34 percent of Capgemini Sogeti to the automobile company Daimler-Benz in 1991 for 5 billion francs, with an option for Daimler-Benz to acquire majority ownership by 1995. At the start of the 1990s, however, the global recession (1990–1991 in the United States, 1990–1993 in parts of Europe, and the start of Japan’s “Lost Decade”) led to the company posting its first annual loss in 1992, which was followed by losses the next two years before reorganization of the firm and improving economic conditions returned the company to profitability in 1995. This included the rapid growth of its facilities management business as well as greater integration internationally to more effectively meet global demands of clients. While funds from Daimler-Benz (and serving this automobile manufacturer’s international IT needs) proved important to reorganization and new initiatives, it was also challenging for both sides. Daimler-Benz’s new leaders in the mid 1990s decided against boosting its stake and instead divested its Capgemini holdings in 1997. Though shorter-lived and less complete than GM’s purchase of EDS, it proved to be a similarly problematic ownership experiment between an automobile manufacturer and IT services provider, where different corporate cultures created hurdles to successful integration.49

In 2000, Capgemini engaged in by far its largest deal to date, acquiring Ernst & Young Technology. The cash-and-stock deal netted the accounting firm $11 billion. For Capgemini, it added 18,000 (mostly consultants) to its labor force, and strongly boosted its resources and capabilities at the intersection of IT consulting and management consulting. After the merger, the newly named Capgemini Ernst & Young had 40,000 employees. For the Big Five accounting firm Ernst & Young, the split (like that of Arthur Andersen with Andersen Consulting/Accenture) reduced real and perceived conflict of interest between its accounting and IT services operations.50

In the early 2000s, Capgemini Ernst & Young accelerated its global delivery of services from various locations and labor forces to enhance efficiency while maintaining attention to the management culture, setting, and needs of clients. In 2003 it trademarked its global delivery system of services as the “Rightshore” concept. This involved major expansion into and continually growing the company’s workforce in India.

By 2008, having shed its awkward three-word name to become Capgemini, the company was operating in thirty countries with four primary business units—Consulting Services, Technology Services (systems integration), Outsourcing Services (including facilities management), and Local Professional Services (tailored to local needs for infrastructure and operations). Its Outsourcing Services grew quickly in the early 2000s to produce 35 percent of the company’s revenue. Like other large IT services companies, Capgemini increasingly focused on sector verticals to meet the needs of major industries and industry clusters. It concentrated on Public Sector; Energy, Utilities, and Chemicals; Financial Services; Manufacturing, Retail, and Distribution; and Telecommunications, Media, and Entertainment. By 2008, Gartner, Inc. listed Capgemini as the sixth largest global IT services company, the five ahead of it being its primary competitors (IBM, HP, Accenture, Fujitsu, and CSC). Other meaningful competitors included the leading Indian firms, Tata Consultancy, Wipro, and Infosys. France and Morocco accounted for 24 percent of Capgemini’s revenue, the United Kingdom and North America adding 22 percent and 19 percent respectively.51 By 2015, like its major competitors, Capgemini was particularly focused on growing its cloud services business. It currently operates in more than forty countries throughout the world and has a global workforce of 180,000, about 85,000 of them in India.52

While Capgemini is the leading European computer services company with reach throughout the world, Fujitsu is the leading Asian computer services company and has a large global presence—fourth in the world in the international industry. Fujitsu began in 1935 as Fuji Tsushinki Manufacturing Company, a 700-person, 3-million-yen spinoff of Fuji Electric (a partnership between Furukawa Electric and Siemens AG of Germany formed in 1923). Fuji Tsushinki Manufacturing consisted of the fast-growing telecommunication, radio, and switching equipment business of its parent company, Fuji Electric. In 1954, enterprising engineers in Fuji Tsushinki Manufacturing’s R&D Department, led by Toshio Ikeda, designed and built the FACOM 100, Japan’s first relay-based electronic computer—an operable, experimental machine that led to the commercial relay-based FACOM 128A Scientific Computer, delivered to the Ministry of Education’s Institute for Statistical Mathematics in September 1956.53 With this, Fuji Tsushinki Manufacturing established itself in the emerging Japanese computer industry, which by the following year included electronic digital computers from two major electronics companies, Hitachi and NEC.

Much like IBM, Fuji Tsushinki Manufacturing bundled engineering, systems, and programming services with early mainframes. In 1963, three years after IBM but earlier than any of IBM’s other competitors, Fuji Tsushinki Manufacturing established a formal program for “Systems Engineers” to aid organizational customers with computer installations. Four years later the company changed its name to Fujitsu Limited (Fujitsu Kabushiki Kisha). Without the anti-trust legal pressures faced by IBM, it continued to bundle the work of Systems Engineers and other computer programming and system support throughout the 1970s and the 1980s.54 This changed in June 1992, when Fujitsu introduced its PROPOSE (“Professional Total Support Service”) framework for delivery of computer services.55 Fujitsu’s PROPOSE, similar to IBM in creatively offering and marketing “solutions” to customers in government and industry, received an award from the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Fujitsu’s history in the 1990s and in subsequent years also parallels IBM in that it offered mainframes (including supercomputers), midrange systems, personal computers, and laptop computers and also focused on rapidly growing services as an increasingly important profit center.56

Fujitsu boosted its computer services (and hardware) infrastructure and geographic presence through acquisition and internal expansion. Back in 1972 it formed an equity and strategic partnership with US computer company Amdahl Corporation, founded two years earlier. Gene Amdahl, who had been one of the lead architects for IBM’s System/360 series in the mid 1960s, launched Amdahl Corporation (in Sunnyvale, California in 1970) to compete with IBM by making IBM-plug-compatible machines. With the early 1970s recession, and short on funds, Amdahl Corporation partnered with Fujitsu. Fujitsu took a 24 percent ownership stake in Amdahl Corporation and provided manufacturing for Amdahl computers. Amdahl Corporation—like many computer manufacturers—bundled some services into hardware contracts. While Amdahl is nearly always mentioned in the computer industry literature as a hardware competitor to IBM, it in fact evolved to become primarily a computer services enterprise by the mid 1990s. Fujitsu had increased its minority ownership stake in Amdahl Corporation to 42 percent by this time period and in 1997 paid $850 million to acquire the remaining 58 percent ownership of the Silicon Valley firm. Fujitsu’s leaders made this move believing their firm needed more than “an arms-length relationship” with the US company and to gain a meaningful foothold in computer services in the US market.57

Figure 10.1 Gene Amdahl, circa 1980s. Courtesy of Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota.

Fujitsu’s leaders also looked to European markets for expansion through acquisition in the 1990s. In 1990 Fujitsu acquired an 80 percent ownership stake in British national champion International Computers Limited (ICL—the product of a series of government-encouraged mergers of early British computer companies British Tabulating Machine Company, Powers-Samas, Ferranti, English Electric, Elliott Automation). ICL—like other global mainframe firms IBM, Sperry Rand, and Control Data—had significant computer services operations and infrastructure. This partial acquisition provided a major boost to Fujitsu’s services business in Great Britain and continental Europe, which was furthered by taking over the remaining 20 percent of ICL in 1998.58

In 1995, Fujitsu opened a major data center, Tatebayashi System Center, in Gunma Prefecture, 120 kilometers northwest of Tokyo, to greatly expand its data processing and facilities management/outsourcing services. Two years later, the company opened another large data center, the Akashi System Center, in Hyogo Prefecture, less than an hour by train from Kyoto. These two data centers and Fujitsu’s early anticipation and strategic push toward cloud computing and the “internet of things” have helped the company achieve its current position as number four in the global computer services industry.

In 1999, Fujitsu announced its “Everything on the Internet” business strategy, and the following year its president, Naoyuki Akikusa, and executive vice president, Yuji Hirose, published on the topic at the IEEE’s Ninth International Symposium of Semiconductor Manufacturing. One component of this strategy was to become the top “provider of internet solutions that merges platforms, information, electronic devices, and services.”59 A major part of these efforts has been a dedicated commitment to reliability. From the start of the “Everything on the Internet” strategy in 1999, its Tatebayashi System Center and Akashi System Center have been central and have undergone substantial expansion and refinement. After the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and power plant disaster, Fujitsu added two new large buildings to its Akashi System Center, an Earthquake Resistant Datacenter and a Seismic Isolation Datacenter.60

Fujitsu also established more than a hundred smaller centers within Japan (roughly two thirds) and throughout much of the world (about one third) in the succeeding two decades. In India, Fujitsu Consulting India Private Limited has IT consulting services centers in Pune, Bangalore, Noida, and Hyderabad that serve customers in 36 countries. In addition to the sizable workforces of IBM, Accenture, Fujitsu, HP, and other multinationals in India, India’s own large-scale computer services companies serve customers all over the world.61

In early 2016, while visiting IBM’s facilities in various Indian cities, CEO Virginia Rometty spoke in Bangalore. “We are today mostly a software and services company,” she proclaimed. “But we have to transform—in this transformation, we will emerge as a cognitive solutions and cloud platform company … . Everything we do is part of that strategy. … This century—the 21st century—will be the Indian century … . I truly believe that India will be the center of this fourth technology shift [meaning a shift to IBM’s analytics/AI, or, as it is currently marketed, “Watson”].”62

IBM’s accelerating investment in its Indian operations (new facilities and rapidly growing workforce) over the past couple of decades—since it returned to the country (after India’s “Economic Liberalization”) with a Tata-IBM joint venture in 1992—is striking. IBM hit an all-time peak employment of 434,245 workers in 2012 (through growth outside the US, especially in India), which declined more than 12 percent to 379,592 by the end of 2014.63 The trade journal Computerworld reported that in 2012 IBM India’s headcount probably had exceeded its US headcount—IBM stopped releasing country employment numbers in 2010. By that time, there was increasing media, public, and government scrutiny of major US corporations’ offshoring of information technology jobs. A union figure published in 2012 placed IBM US employees at less than 93,000.64 Computerworld obtained an internal IBM document (that it stated the company would not verify for the trade journal) that placed IBM India employment at 6,000 in 2002 and 112,000 by 2012—and reported the average salary for IBM India employees in 2012 to be about $17,000 a year (a highly competitive IT industry salary in India at the time).65 Most IBM India employees are on the services side, and Rometty’s remarks probably were made to reassure traditional IT services employees about their place (and India’s) in the company’s future—an enterprise undergoing a major transformation in which services remain central but the types of services and the skill sets that are sought are changing with the increased concentration on cloud computing and on analytics.

In the 1990s and the early 2000s India’s IT services industry (including its workforce at multinationals such as IBM, Accenture, CSC, and Capgemini, as well as emerging Indian giants Tata Consultancy, Wipro, and Infosys) was engaged primarily on the lower-end, commodity side of the computer services industry—debugging for Y2K, and later the outsourcing of fairly basic business processes. The lower end of the industry was derisively referred to in the global industry and trade press as commoditized “body shops”—implying “jobs that just about any IT worker could do.” At that time, that India might be at or near the forefront of innovation for a legendary US-based global IT company (IBM) might have seemed hard to believe. Since then, however, a significant portion of Indian IT workers at multinationals and native giants have moved beyond “body shop” services to more complex and lucrative “verticals” of specialized software systems catered to specific industries and company needs. In view of this and the comments Rometty made during her 2016 visit to India, IBM’s strategy for Watson in India seems not just plausible but probably advisable, owing to the high level of talent and the lower salaries. How did India make the transition so quickly?

The historian Ross Bassett, in his 2016 book The Technological Indian, helps answer this important question by looking at deeper, longstanding foundations. Bassett insightfully examines Indian engineering graduates from MIT—a modest number of late-nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century pioneers before India’s 1947 independence and many hundreds since—and the outsized influence of these often visionary individuals on ideas about technology and on Indian educational institutions (the Indian Institutes of Technology, particularly IIT-Kanpur), and Indian companies (especially those in the Tata Group, which in the late 1960s launched the first Indian international IT services company, Tata Consultancy). Bassett demonstrates how the bonds of technological elites in the US and India were deep, even when relations between these two democratic nations were strained during the early years of the Cold War.66 Thanks to MIT’s unrivaled early presence in computing in the 1950s and the 1960s (with Whirlwind, SAGE, CTSS, Project MAC, Multics, and pioneering work in artificial intelligence research), a number of Indians studying at MIT were exposed to (and contributed to) important advances in computer and software technologies.

Tata Consultancy owed its origins to three MIT Project MAC graduates. In 1963, Lalit Kanodia, who had a degree in mechanical engineering from IIT-Bombay, left India for graduate study in industrial engineering at MIT. Exposed to computing through graduate assistantships at the well-funded and rapidly growing Project MAC, he became deeply interested in computing and its potential applications, doing consulting work at both Ford Motor Company and Arthur D. Little. On his return to India in 1965, a neighbor introduced him to Rustom Choksi, an executive with the Tata Group (a giant multinational industrial conglomerate). The ambitious young graduate proposed to Choksi and others at Tata ways the Tata Group could improve efficiency in its dozens of businesses by managing electrical loads and financial accounting by means of computer applications. Forward-thinking Tata executives gave Kanodia an unusual opportunity to return to MIT for a doctorate and then to launch (with two other Indian MIT graduates, Ashok Malhottra and Nitin Patel) a venture in computing to help Tata better apply IT internally. In September 1967, a Tata Computer Centre was launched with the installation of an IBM 1401. In the center’s first year, the three young engineers gave many talks to managers at various Tata companies on possible computer applications. All too often, long-serving managers accustomed to existing systems and methods were unreceptive. Top Tata executives, however, saw a potential for outside business, and in 1968 the Tata Consultancy was born. Kanodia, with an entrepreneurial mindset and wanting to own and run a firm rather than to head what was at the time a tiny business group within a giant conglomerate, left the following year and founded Datamatics Staffing, a recruitment company that offered computer education courses. After obtaining an IBM 1401 in the late 1970s, Kanodia founded Datamatics Consultants to concentrate on financial and accounting business data processing.67

With Kanodia’s departure, F. C. Kohli of Tata Electric, who held an MS degree from MIT, became general manager and managing director of Tata Consultancy Services (TCS). In 1969, TCS secured a contract to handle computer-generated billing for the Bombay telephone system with 140,000 customers. With international aspirations from the start, TCS partnered with Burroughs Corporation on small contracts, and obtained some independent business, but overall the 1970s were characterized by slow growth, and crippling government bureaucracy and conditions—in particular, tough exchange rates and related restrictions on importing computing equipment. And beyond government hurdles, other hurdles were presented by the policies of IBM, the world’s leading vendor of mainframe computers to India and rest of the world.68

The government of India had ongoing but strained relations with IBM, which had begun doing business in India in 1951. The government (and Indian industry) grew to resent IBM for selling only its older computers in India—systems often possessing little value in developed markets. By the late 1960s this meant importing used IBM 1401s. Soon IBM set up factory facilities in India to repair, refurbish, and rebuild 1401s. These machines were then leased to Indian banks, insurance companies, steel companies, airlines, public utilities, and other firms and organizations. The largest customer was India Railways, which ran fourteen IBM 1401–based computer centers to enhance operational efficiency. IBM’s strategy of selling only older systems in India continually antagonized that country’s government, and government leaders proceeded to investigate amending rules and restrictions on international companies operating in India. In the mid 1970s, IBM executives and the government of India engaged in increasingly tense negotiations. The IBM negotiating group made some concessions (regarding newer machines and a proposed new software center), but the concessions were too little and too late. In 1977 the government of India demanded that IBM relinquish majority ownership of the Indian operation to it. IBM’s CEO, Frank Cary, was unwilling to substantially dilute IBM’s equity in India and to relinquish control, and IBM officially left India in June 1978, selling already installed (but at the time leased) machines at a great discount to Indian customers.69 IBM did not return until 1992 (a year after the start of India’s economic liberalization), when it entered into a partnership with the Tata Group. Though the small joint venture grew, a half-decade passed before IBM moved into the market more substantially with a second initiative. The latter joint venture was 80 percent IBM Global Services and 20 percent Tata Group. In 1998, IBM established an IBM Research Laboratory at IIT-Delhi. Tata divested itself of both joint ventures with IBM in 1999, and the new IBM India has grown rapidly ever since.70

In the late 1970s, another MIT graduate, Narendra Patni, who had previously worked with Jay Forrester and at Arthur D. Little, launched a small computer enterprise, which then partnered with Data General to market that company’s minicomputers in India. To meet the foreign exchange requirement, Patni’s company hired a dozen programmers to add value by writing software for the Data General systems. The lead programmer, Narayana Murthy, had gone to IIT-Kanpur to get an MS in electrical engineering in preparation for a career in the electrical power industry. At IIT-Kanpur, Murthy was captivated by computers and developed strong programming skills. Murthy left Patni’s enterprise in 1981 and (along with a half dozen others) formed an IT services company called Infosys, which with Tata Consultancy Services and Wipro would make up the triumvirate of emerging IT services giants in India. Wipro, in contrast to the IT startup Infosys, evolved into a computer services firm as its IT services division greatly outpaced its other businesses.71

Mohamed Hasham Premji launched Western India Products Limited as a vegetable oil firm in 1945. After several decades of focusing on producing vegetable oils and related chemical products, he expanded and diversified the business, first into industrial equipment (hydraulic cylinders) in the mid 1970s, and then into computing. In 1980 he founded Wipro Information Technology Limited (Wipro ITL) in Bangalore. Wipro, which was similar to the Tata Group but not nearly as large, was a conglomerate of businesses, one being Wipro ITL. This computing firm provided hardware, peripherals, and services (programming, maintenance, and training).72 Whereas the Tata Consultancy, though very large, is just one among other giant companies in the Tata Group, Wipro Information Technology Limited (later shortened to Wipro Technologies) came to be Wipro’s dominant business, and its rapid growth helped to make Bangalore the IT center it is today.73

Two later entrants, Satyam Computer Services Limited/Cognizant and HCL Technologies, rounded out what would become India’s Big Five. Satyam Computer Services was founded in Hyderabad in 1992. Dun & Bradstreet (D&B), a credit reporting and business information specialist based in New Jersey, formed a major partnership with Satyam in 1996. That year, D&B spun off its internal IT unit (which had been created to deal with Y2K readiness) to engage in contract external IT services. The Indian entrepreneur Chintalapati Srinivasa Raju (widely known as Srini Raju) and his D&B IT unit partnered with Satyam to become Dun & Bradstreet Satyam Software (DBSS), an IT services firm three fourths owned by D&B and one fourth by Satyam (D&B later bought out Satyam’s share). For Dun & Bradstreet, DBSS was a means of quickly acquiring an Indian IT services workforce. (Eventually, roughly two thirds of the workforce of DBSS was based in India, which led many analysts and journalists to consider it an India firm.) In the late 1990s, Dun & Bradstreet spun off DBSS, which changed its name to Cognizant Technology Solutions Corporation.74

HCL Technologies (originally HCL Overseas Limited), the smallest of the five IT services giants, used a joint venture to advantage, as Cognizant did. Formed in 1991, HCL Technologies grew slowly before partnering with Perot Systems in 1996. Until the early 2000s, HCL Technologies also focused on lower-value basic business process outsourcing (BPO) and related services. Since then, it has built a highly skilled workforce. It leveraged Perot Systems customer connections to provide higher-value advanced application system services to major multinationals such as the KLA-Tencor Corporation, NCR, and Toshiba.75 More generally, Indian IT firms reinvested profits to expand their capabilities to begin to transition from exclusively lower-level work (such as BPO) to a mix that included assignments further up the value chain.

Throughout the 1980s, Tata Consultancy Services, despite international aspirations and a partnership with Burroughs, primarily served Indian customers, as did Wipro and Infosys. Travel outside India was expensive, and the telecommunications infrastructure for international computer networking was limited. Furthermore, international telecommunication-based data transmissions were expensive. Texas Instruments, struggling in the early 1980s in the US, established operations in India in 1982, and in 1985 set up a satellite-based data communication infrastructure to connect its Bangalore Software Development operation to London, and from London to the US. For IT enterprises, this established a model for, and demonstrated the feasibility of, international data networks connecting a developing country with developed countries.76 In the early 1990s, with this model in place, India’s economic liberalization quickly brought new IT opportunities to India’s hardware, software, and IT services businesses.

The government of India and Indian IT services firms saw providing software and programming services to overseas clients (particularly in the United States) as a major opportunity, forecasting that the export business of roughly $164 million in 1991 could grow to $1 billion a year by 1996.77 However, programmers’ skills varied widely, and project management experience and expertise often were in short supply. Quality-related problems associated with programming projects and with debugging efforts were not unique to India; they also existed in the United States and throughout the world. The US Air Force, having fallen victim to a number of failed internal and contracted programming projects (such as the Advanced Logistic System project in the 1970s), sought to develop a framework for certifying software/system quality standards.78 It contracted with Carnegie-Mellon University’s Software Engineering Institute (SEI) and with the MITRE Corporation to develop the SEI Capability Maturity Model (CMM), with Watts Humphrey (the founding director of the SEI Software Process Program, and a former director of the IBM Systems Research Institute) leading the effort.79 The first version of the CMM was circulated for feedback in 1991 and was then published in a 1992 technical report as Version 1.1. At the CMM’s lowest levels (levels 1 and 2), processes are unpredictable and reactive; at levels, 3, 4, and 5, respectively, processes are defined, quantitatively managed, and fully controlled and optimized.80

Motorola, which had suffered problems with software quality, utilized a new Motorola India Electronics Limited development group as a test bed for instituting CMM Version 1.0 in 1991. Using CMM, that group achieved level 5 in its first year. The CMM is focused on complete documentation and process controls—something far easier to start anew with a dedicated, talented group than institute at an established facility that has set practices and workplace cultures, and is prone to cut corners with documentation. The publicity of Motorola’s success led Wipro ITL and other IT services firms to invest heavily in CMM. Wipro was the second company to achieve level 5 (in 1998). In February 2000, India had ten level 5 firms and fourteen level 4 firms.81 CMM was used in the US and around the world, but nowhere was it embraced as quickly, fully, and as successfully as in India. It was a mechanism for assuring quality and encouraging US clients to sign contracts with Indian computer services firms; it also was a mechanism for improving processes, which could help with efficiency, meeting delivery schedules for working systems, and long-term cost containment (through minimizing expensive and laborious debugging). Indian IT services corporations also enthusiastically embraced other quality metrics, methods, and credentialing, such as ISO 9000 and Total Quality Management (TQM).

The “Millennium Bug” or “Y2K problem” resulted from the use of only two digits for a year in COBOL and other programming. (The practice dated from the late 1950s, when computer memory was limited and expensive.) Before the 1990s, use of only two digits for a year was extremely common. The legacy of two-digit code for years led to widespread fears that computer systems would go down or would operate erratically at the turn of the millennium. Hundreds of billions of dollars were spent worldwide in the second half of the 1990s (mostly between 1996 and late 1999) on “Y2K compliance.” Leading market research firms’ estimates of the costs of Y2K readiness varied widely. The Gartner Group’s estimate of the worldwide cost, which was roughly in the middle, was $600 billion. Merrill Lynch alone spent more than half a billion dollars on Y2K readiness. Few US corporations ever revealed their expenditures on Y2K readiness. The US government, local governments, corporations, and other organizations probably spent well in excess of a hundred billion dollars.82

Efforts to become Y2K compliant caused a labor shortage of people skilled at debugging COBOL code. Some Indian firms well up the ladder of certification on the CMM, Wipro among them, stepped up. They could not have done so without the strong, educated workforce the IITs had provided or without the networking infrastructure Texas Instruments and other companies had pioneered.

Tata Consultancy set up a “Y2K factory” in the Indian city of Chennai (called Madras before 1996). There about a thousand programmers went through approximately 2 million lines of code per day and made fixes. As the deadline grew closer, Tata Consultancy Services contracted out some of the work to seven other computer services firms in India. Infosys and Wipro also made substantial commitments and benefited from large-scale Y2K compliance work, most of it for US organizations. For Infosys, 23 percent of 1998 revenue and 20 percent of 1999 revenue was from Y2K compliance code checking and fixes.83 These efforts not only produced revenue that enabled Indian companies to expand; they also provided opportunities to demonstrate reliable performance on technical work (albeit on a rather low level) and to establish relationships with American and multinational corporations. This helped set up India’s largest computer services providers to be leaders in business process outsourcing in the early 2000s and in subsequent years.

Business process outsourcing is a broad category referring to accounting systems, payroll systems, human resources systems, supply chain management systems, and many other types of IT or computer services. It also can refer to the business activity of taking calls from customers and providing customer service (on billing or other questions)—not primarily an IT service, with the exception of help-desk work that assists customers with IT equipment, networking, or software. The outsourcing of business processes by US corporations and organizations to India involved both traditional computer services (back-office processing) and customer-service call centers.

In a 2005 book titled The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Friedman discussed the phenomenon of the United States and other developed nations outsourcing IT services and call centers to developing countries, particularly India. According to Friedman, it was during a trip to India shortly before he began writing the aforementioned book that he came up with the metaphor “the world is flat” to characterize computer networking precipitating a large-scale round of globalization applying to information and computer services—essentially, technology leading to a level playing field for work and commerce.84 Although the metaphor is clever, it is somewhat distorting. The world may be leveling to a degree, but because of different geographies, resources, populations, histories, cultures, customs, governments, laws, and other factors it will never be truly “flat”—that is, equal in opportunities for enterprise and wages. And frequent in-person interaction with clients or team members can make a difference.85 Direct personal interaction can be quite helpful in applications programming and systems integration projects, whether a particular project involves an independent contractor providing networking support services to a small nonprofit organization, or a sizable company installing a new system for management of its supply chain, or a massive real-time system for the US Department of Defense. The business of computer services has always been a reputation-based business, and face-to-face interaction often can be helpful. The movement toward cloud services (discussed more fully later in this chapter) certainly increases opportunity for work at a distance, but also has produced substantial physical infrastructure. Thus far, many of the largest data centers and server farms are in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, France, Japan, and Australia—some of the most expensive countries in terms of land and labor. And those facilities require considerable work to build and to maintain.

Journalistic reports of the outsourcing of IT (including Friedman’s op-ed columns in the New York Times and his book The World Is Flat) have led to a backlash in the popular press, among politicians, and among the public concerning the loss of well-paying jobs in an industry to which the US has contributed more innovation than any other country. Although some US-based jobs have shifted overseas, there has been considerable growth in US computer systems and IT services jobs in the past two decades, including in the half-dozen years after Friedman’s book. The bursting of the dot-com bubble caused the only multi-year downturn (2001–2003) in computer system and IT services employment in the past 25 years. The recent Great Recession brought only a one-year decline of 1 percent (in 2009). As the Bureau of Labor Statistics noted in a 2013 report on employment in IT services and in computer system design, from 2003 to 2011 US labor force in those fields grew by 37 percent (despite the Great Recession), exceeding 1.5 million employees by 2011.86 Thus, even though IBM and some other of the largest IT services companies have reduced their US labor forces in recent years and increased their labor forces in India, many IT jobs remain in the US, and many more jobs have been created at smaller, mid-size, and large firms (including Google, Facebook, Salesforce.com, Amazon, and Rackspace) in the broad IT services industry.

In 2012, Tata Consultancy Services was the sixteenth-largest global IT services company in revenue, at $10.9 billion. Within three years, its $15.5 billion in annual revenue placed it in the top ten.87 In 2014 the Indian IT services industry had revenues of more than $70 billion.88 Tata Consultancy’s workforce of more than 319,000 is larger than that of HP Enterprise and roughly comparable to that of Accenture and (probably) to that of IBM’s Global Services Division.89 Like Wipro, Infosys, HCL, and Cognizant, TCS has made significant shifts to cloud services, analytics, and other higher-margin areas. But TCS’s revenue is only about half of Accenture’s and less than a third of IBM Global Services. It has higher margins, but to secure business it still charges far less (and pays significantly less in total compensation) than the global average for IBM and Accenture. We are still far from a truly “flat” world. And, as the convergence lessens the labor cost divide (to become a bit flatter), the pace of outsourcing to India is likely to slow. Already there has been a shifting geography of IT labor to some other low-cost countries, including China, Argentina, the Philippines, Egypt, and Bulgaria.90

Today in India, the salaries of programmers with little experience (less than five years) tend to be quite low by US standards—under $12,000 a year. However, often such a programmer can double his or her salary (or increase it even more) after a decade of experience and a willingness to leave for another job.91 And based on purchasing power parity, the differences in compensation between the United States and India in IT services are less stark.92 Turnover is high in the Indian IT industry, a constant struggle for Indian firms (where the annualized percentage of those voluntarily leaving Tata Consultancy is now around 15 percent and numbers have been higher at Infosys).93 To keep senior highly talented software developers, salaries in India at times have begun to approach pay levels in the US or European countries. Clearly higher-end software development and systems integration work is being outsourced, not only the low-level debugging and basic business process work. At the same time, this comes at a substantially higher price (to clients) than “body shop” labor and puts increasingly critical systems outside the ready reach of companies in the US, Europe, and developed countries in Asia. The overall IT services wage gap in the early years of outsourcing (late 1990s and the early 2000s) could result in savings that amounted to being five times cheaper in view of the disparity between labor costs in India and those in the United States. Now the differences are far less than twice for experienced software developers and analysts, and that disparity in compensation is continuing to diminish.94 India has had higher single-digit inflation for years and talented programmers and systems analysts can command salary increases far in excess of cost of living growth—to keep top IT talent sometimes requires annual increases of 10–30 percent.95 Job hopping is a frequent tool for experienced and talented IT professionals (and for less experienced people) to increase their salary.

The easier jobs to outsource were outsourced in the early 2000s. Now managers, in deciding about the more complex ones, are faced with diminished savings that do not always seem to justify real or perceived higher risks. Some large US corporations have been keeping more work in house in recent years, often working locally with IT services providers in order to have better control, or at least a better sense of control. Others are focused on shifting IT to cloud providers. All the Indian majors, like the multinationals, are concentrating on security as never before, but high-profile breaches at corporations can potentially make a services supplier halfway around the world less attractive. And while all the Indian giants have become cloud services players, Amazon, Microsoft, IBM, Accenture, HP, and others have been aggressive in shifting to this new paradigm and at present appear to be extremely well positioned for this field. The geographical and demographic labor impact with the switch to cloud services remains to be seen.

In late 1965, as the Rolling Stones released “Get Off of My Cloud” (a follow-up single to “Satisfaction”), time sharing—a precursor of “cloud computing” with a lineage broken apart by a two-decade preference for using local computer resources (PCs and local servers)—was just getting started commercially (by GE and Tymshare) and certainly was not on the minds of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards,96 the song was about wanting solitude and not being hassled or held back—being left alone and free in a private, peaceful place.

Time sharing of the mid 1960s through the 1980s—as a technology and a business—has important commonalities with the cloud computing of the past decade. These include information technology services companies selling remote computer resources and associated services—storage, processing, and software—over a network either to supplement or in place of directly possessing such resources. The time-sharing segment of the computer services industry had a deeper history dating back to origins of computer networks—to Whirlwind, SAGE, the first proprietary networks, and the ARPANET. And computer networks had a deep connection and built upon much earlier infrastructural networks (to lay cable, create network exchanges, and install other equipment)—railroads, telegraphy, sewers, highways, and so on. After all, the Internet provider Sprint was a 1978 spinoff of a railroad company—its name stands for Southern Pacific Railroad Internal Network.