LIVESTOCK OWNERS EVERYWHERE AGREE: It’s a heartbreaking, financial disaster when predators raid your flocks and herds and kill your animal friends. Predators are everywhere, from free-roaming suburban dogs to packs of ubiquitous coyotes to mountain lions in up-country meadows, and they all pose a threat to miniature livestock. One of the best ways to protect against predators is to keep a livestock guardian or two.

Consider losses among full-size sheep and goats. The United States Department of Agriculture’s National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) keeps track of what kills American sheep and goats and periodically publishes findings in a report titled “Sheep and Goats Death Loss.” According to the report, predators killed 280,000 sheep and goats during 2004, accounting for slightly more than 37 percent of each species that died of all causes that year! These sheep and goats were killed mainly by coyotes (more than 60 percent of the total) but also by dogs, mountain lions, bears, foxes, eagles, bobcats, and other species (among them wolves, ravens, and black vultures).

Predation is a serious problem, and one you’ll have to address in order to raise small livestock anywhere in North America — even in relatively populated areas, where dog predation poses a serious risk.

When NASS surveyed sheep and goat producers to ask how they managed predation in 2004, almost 53 percent indicated they relied at least in part on predator-proof fencing; 33 percent also penned their stock at night; and 55 percent kept livestock guardian animals with their flocks and herds.

The concept of livestock guardian animals goes back a long, long way — about 6,000 years to be precise — to Turkey, Iraq, and Syria, where dogs were first trained to protect sheep and goats. Savvy livestock owners still use guardian dogs to protect their livestock, but some have added guardian donkeys and llamas to the mix.

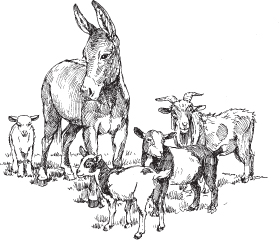

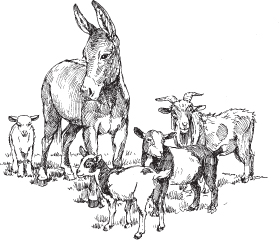

Donkeys are born with an inherent hatred for anything that (to them) resembles a wolf. Therefore, some donkeys make first-rate herd guardians where coyotes and dogs are troublesome.

Donkeys require no specialized training; they simply dislike dogs and coyotes. They chase while braying, biting, and sometimes pawing or kicking at canid invaders. Donkeys have keen hearing and good eyesight, so dogs and coyotes rarely sneak past a donkey on guard.

They are hardy; long-lived (25- to 30-year life spans are the norm); and with the exception of medicated feed laced with Rumensin (which is poisonous to equines of all kinds), they eat the same sorts of things you probably already have on hand to feed ruminants such as miniature cattle, sheep, goats, and llamas. And you won’t break the bank buying a guardian-quality, standard-size or larger donkey. You can usually buy one locally in the $100 to $800 price range, depending on quality, registration status, and size.

Full-size donkeys make good livestock guardians for miniature goats.

There are disadvantages, however:

1. Gelded (castrated male) donkeys make the best guardians; jennets (females, also called jennies) run a close second. But some jacks (intact males) are aggressive toward humans, most will savage animals they dislike, and many have been known to kill newborn kids and lambs. Also, some jacks try to breed the larger female livestock they’re hired to protect, sometimes inflicting serious, even fatal, injuries in the process.

2. Donkeys prefer the company of other donkeys. If you place several guardian donkeys with a flock or herd, or pasture your flock next to a field containing donkeys or other equines, most donkeys will hang out with their own kind instead of watching their charges.

3. Unlike guardian dogs, donkeys haven’t been bred for generations to look after other livestock; some simply aren’t interested in bonding with animals not of their kind.

If you buy a donkey to guard your herd, ask if you can return him if he’s aggressive toward or disinterested in the livestock he’s supposed to guard. Chances are good, however, that a carefully chosen donkey will do the job in spades. In one survey, 59 percent of Texas producers who use guardian donkeys rated them as good or fair for deterring coyote predation and another 20 percent deemed them to be excellent or good.

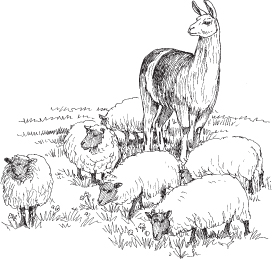

In 1990, researchers at Iowa State University polled 145 sheep producers in five western states to determine the effectiveness of llamas for reducing dog and coyote predation. The producers reported losing an average of 21 percent of their ewes and lambs each year prior to adding llama guardians and only 7 percent after guardian llamas joined their flocks. Eighty percent rated their llamas effective or very effective for guarding sheep. In another study conducted in Utah, 90 percent of sheep producers rated guardian llamas effective or very effective on the job. NASS figures indicate that 14 percent of sheep and goat producers maintained guardian llamas in 2004.

Just like donkeys, llamas naturally dislike dogs and coyotes. Many make excellent guardians; others make poor guardians. Llamas prefer the company of other llamas, so you usually have to keep just one per pen or herd. Intact males are often aggressive and may try to breed small females of other species. A guardian-quality, gelded llama costs roughly $200 to $750; females usually sell for somewhat more. Llamas have certain advantages and disadvantages when compared with donkeys:

Llamas require the same food (unlike with donkeys, it’s safe to feed them Rumensin-medicated products), vaccinations, and foot care as other small ruminants. It’s easy to treat them as just another member of the herd or flock.

Llamas require the same food (unlike with donkeys, it’s safe to feed them Rumensin-medicated products), vaccinations, and foot care as other small ruminants. It’s easy to treat them as just another member of the herd or flock.

Llamas, however, are more aloof than donkeys. While most donkeys crave human interaction, the average llama doesn’t. This makes it more difficult to catch and handle them for routine maintenance chores.

Llamas, however, are more aloof than donkeys. While most donkeys crave human interaction, the average llama doesn’t. This makes it more difficult to catch and handle them for routine maintenance chores.

Llamas don’t do well in hot, muggy climates, where they’re prone to heat exhaustion. Depending on the length of their fleeces, llamas require full or partial shearing at least once a year.

Llamas don’t do well in hot, muggy climates, where they’re prone to heat exhaustion. Depending on the length of their fleeces, llamas require full or partial shearing at least once a year.

Llamas don’t live as long as donkeys. The average llama lives 15 years.

Llamas don’t live as long as donkeys. The average llama lives 15 years.

Some full-size llamas make superlative livestock guardians.

For thousands of years, stalwart European, Middle Eastern, and Asian guard dogs of dozens of types and breeds have watched over herds of goats and flocks of sheep, protecting them from predation by wolves, bears, jackals, and human thieves.

Some of these dogs eventually made their way to North America. Now, according to current NASS figures, nearly 33 percent of American sheep and goat producers use livestock guardian dogs, representing 20 or more breeds.

All of the livestock guardian breeds are large, intelligent, strong-willed, and potentially aggressive and dominant dogs, so they aren’t to be casually handled by the faint of heart. Most are aggressive toward other dogs; they sometimes kill household pets that wander in with their charges, and some fight to the death with other guardian dogs of the same sex.

Since most predators strike at night, livestock guardian dogs are most active after dark. Barking is their primary means of warning off intruders, so expect a lot of nighttime barking from your LGDs.

Before buying a livestock guardian dog, visit LGD breeders and livestock owners who keep them. Compare philosophies and training methods. Know what you’re getting into before you bring a dog home.

It’s best to buy an adult dog that is already familiar with guarding the species you raise, but if buying a puppy is your only option, here are a few pointers to keep in mind:

To be effective, livestock guardian dogs must be bonded to and stay with the livestock they’re expected to guard. During their prime socialization period (from 4 to 14 weeks of age), it’s important to minimize human interaction with LGD puppies. However, don’t believe those who insist a guardian puppy should never be cuddled or played with. LGD puppies should look forward to interacting with humans, but it’s important to play with the puppy on her own turf rather than taking her to the house or for rides in the truck; she needs to understand that watching her livestock pals is her primary job.

To be effective, livestock guardian dogs must be bonded to and stay with the livestock they’re expected to guard. During their prime socialization period (from 4 to 14 weeks of age), it’s important to minimize human interaction with LGD puppies. However, don’t believe those who insist a guardian puppy should never be cuddled or played with. LGD puppies should look forward to interacting with humans, but it’s important to play with the puppy on her own turf rather than taking her to the house or for rides in the truck; she needs to understand that watching her livestock pals is her primary job.

Livestock guardian puppies needn’t be trained to watch their charges; the desire to guard has been bred into these dogs for thousands of years. Most begin showing guardian dog behaviors by five or six months of age (scent marking, purposeful barking, and deliberate patrolling), although few become reliable protectors until they achieve mental and physical maturity, usually at about two years of age.

Livestock guardian puppies needn’t be trained to watch their charges; the desire to guard has been bred into these dogs for thousands of years. Most begin showing guardian dog behaviors by five or six months of age (scent marking, purposeful barking, and deliberate patrolling), although few become reliable protectors until they achieve mental and physical maturity, usually at about two years of age.

As they pass through adolescence, most LGD puppies exhibit inappropriate behavior toward their charges, usually in the form of play-chasing. Expect it and work through this phase with reprimands; there’s an effective working livestock guardian waiting on the other side.

As they pass through adolescence, most LGD puppies exhibit inappropriate behavior toward their charges, usually in the form of play-chasing. Expect it and work through this phase with reprimands; there’s an effective working livestock guardian waiting on the other side.

The occasional pup comes along who has no interest in guarding. All breed organizations maintain rescue programs for their dogs, so if you get one of these apathetic types, consider placing your nonworking dog with a rescue group.

The occasional pup comes along who has no interest in guarding. All breed organizations maintain rescue programs for their dogs, so if you get one of these apathetic types, consider placing your nonworking dog with a rescue group.

The following are descriptions of most of the bona fide livestock guardian dog breeds currently available in North America.

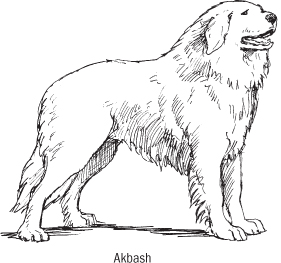

Origin: The Akbash region of Turkey

Name in native land: Akbas (“white head”); Coban Kopegi (pronounced cho-bawn co-pey; “shepherd’s dog”)

Height: 28–32 inches (71–81 cm)

Weight: 90–130 pounds (40.5–58.5 kg)

Coat types: Short to medium-length double coat

Color: White

Life span: 10–11 years

The Akbash is leaner and leggier than the other Turkish guardian dog breeds. It’s a highly effective guardian dog, though more aloof toward humans than are some breeds. In Turkey, the Akbash is prized for its intelligence, bravery, independence, and loyalty — qualities that endear it to its North American admirers, too. Although cases of hip dysplasia occur in Akbash dogs, it occurs less frequently than in most other livestock guardian breeds.

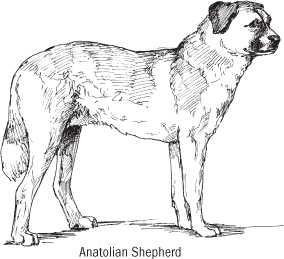

Origin: Semi-arid Anatolian Plateau of central Turkey

Name in native land: Anadolu Coban Kopegi (pronounced cho-bawn co-pey; “Anatolian shepherd’s dog”)

Height: Dogs 28–35 inches (71–89 cm); bitches 26–28 inches (66–71 cm)

Weight: Dogs 100–160 pounds (45–72 kg); bitches 90–130 pounds (40.5–58.5 kg)

Coat types: Short to medium-length double coat

Color: Usually fawn with a black mask, but any color is acceptable

Life span: 10–15 years

The Anatolian Shepherd is one of the most popular of the livestock guardian breeds. It was developed to be independent and forceful, responsible for guarding its master’s flocks without human assistance or direction. Anatolians are known for their strength and courage. Because they’re suspicious of and often aggressive toward strangers, they work best in situations where they don’t come in constant contact with unaccompanied friendly visitors, though they’re in their element against predation by humans. Both the American Kennel Club and the United Kennel Club recognize and register Anatolian Shepherds.

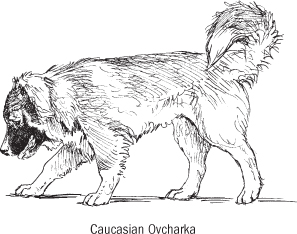

Origin: The Caucasus mountain region of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Russia

Name in native land: Kavkazskaya Ovcharka in Russian, Nagazi in the Georgian Republic, and Gampr in Armenia

Height: 25–32 inches (63.5–81 cm)

Weight: 100–150 pounds (45–67.5 kg)

Coat types: Short or long; double-coated; abundant ruff and fringing

Color: Usually agouti gray; otherwise any color except red and white like the Saint Bernard, solid black or brown, or solid black and tan

Life span: 10–11 years

Ovcharka is a generic Russian word meaning “shepherd’s dog”; also spelled ovtcharka and owtcharka, the word is pronounced uhf-char-ka. Caucasian Ovcharkas mature slowly and are somewhat prone to hip and elbow dysplasia. Caucasian Ovcharkas were extensively used as military guard dogs throughout the former Soviet Union. I’m told Ovcharkas are rather like Chow Chows — friendly but watchful.

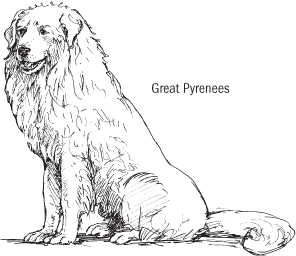

Origin: The Pyrenees mountain region of southern France and northern Spain

Name in native land: Chien des Pyrénées, Chien de Montagne des Pyrénées

American nickname: Pyr

Height: Dogs 27–32 inches (68.5–81 cm); bitches 25–32 inches (63.5–81 cm)

Weight: Dogs from 100 pounds (45 kg), bitches from 80 pounds (36 kg)

Coat types: Long, coarse outer coat may be straight or slightly wavy; fine undercoat, soft and thick

Color: White, often with gray or tan “badger markings” on the head and occasionally spotting on the body or tail. The color of the nose and the eye rims should be jet black.

Life span: 10–12 years

Great Pyrenees are considered one of the most human-friendly of livestock guardian breeds, making them ideal for use on small acreages with nearby neighbors. Some owners say they patrol out farther than other breeds, making secure fencing a must. Great Pyrenees have double dewclaws on their hind legs. They are somewhat prone to hip dysplasia and, occasionally, skin problems. In North America, they are recognized by both the American Kennel Club and the United Kennel Club.

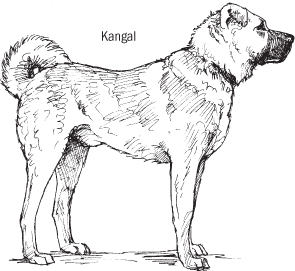

Origin: Kangal District of Sivas Province in central Turkey

Name in native land: Karabash (“black head”)

Height: Dogs 30–32 inches (76–81 cm); bitches 28–30 inches (71–76 cm)

Weight: Dogs 110–145 pounds (50–66 kg); bitches 90–120 pounds (41–54 kg)

Coat type: Short, dense double coat

Color: Light dun to gray with black mask and ears

Life span: 11–14 years

Kangal Dogs are recognized by the United Kennel Club. Some authorities lump Kangal Dogs and Anatolian Shepherds together, but they are similar yet different breeds. According to the Turkish Shepherd Dogs Web site FAQs:

The lineal and weight requirements for Kangal Dogs and Anatolians are different.

The lineal and weight requirements for Kangal Dogs and Anatolians are different.

Kangal Dog color is restricted. Anatolians are acceptable in all colors, patterns, and markings.

Kangal Dog color is restricted. Anatolians are acceptable in all colors, patterns, and markings.

The Kangal Dog is short-coated. The Anatolian coat may be up to four inches in length.

The Kangal Dog is short-coated. The Anatolian coat may be up to four inches in length.

Kangal Dogs registered with the UKC originate, or descend from, dogs obtained from the Sivas-Kangal region of Turkey. Anatolians appear to originate from any area of Turkey.

Kangal Dogs registered with the UKC originate, or descend from, dogs obtained from the Sivas-Kangal region of Turkey. Anatolians appear to originate from any area of Turkey.

Their temperaments are different. The Kangal Dog is people oriented and only hostile to traditional predators.

Their temperaments are different. The Kangal Dog is people oriented and only hostile to traditional predators.

Origin: Bulgaria

Name in native land: Karakachansko Kuche

Height: Dogs 25–29 inches (64–74 cm); bitches 23.5–27.5 inches (60–70 cm)

Weight: Dogs 85–110 pounds (39–50 kg); bitches 75–100 pounds (34–45 kg)

Coat types: Short-haired (hair up to about 2⅓ inches in length), long-haired (anything over 2⅓ inches); ruff; feathering on legs; long hair on tail; double-coated

Color: Most are spotted, but solid-colored dogs are acceptable; colored areas can be black, gray, brown, yellow, or brindle.

Life span: 12–16 years

This breed is critically endangered worldwide; breeders in the United States are working to preserve this extremely ancient, effective livestock guardian breed before it becomes extinct.

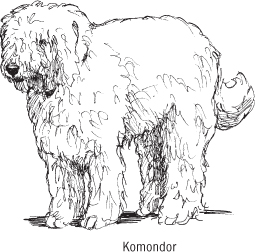

Origin: Hungary

Name in native land: Komondor (pronounced KOM-ahn-door; plural is Komondorok; the name Komondor may be derived from the term komondor kedvu, meaning “somber” or “angry”)

Height: 25.5 inches (65 cm) and up

Weight: Dogs up to 125 pounds (57 kg); bitches 10 percent less

Coat type: Very long, nonshedding double coat. Show people divide it into sections and allow felted cords to form; clipping working Komondorok once a year is a better solution.

Life span: 10–12 years

Komondorok are prone to hip dysplasia, bloat, and skin diseases. It is one of the strongest and most aggressive of the livestock guardian breeds. The Komondor is one of the most effective breeds in guarding herds against human thieves. Komondorok are recognized by both the American Kennel Club and the United Kennel Club.

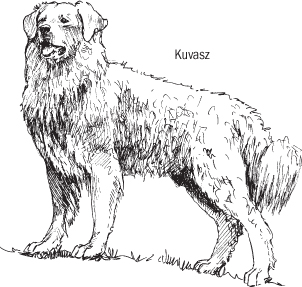

Origin: Hungary

Name in native land: Kuvasz (pronounced KOO-vahz); plural is Kuvaszok. The name most likely comes from the Turkish word kavas, meaning “guard” or “soldier,” or kuwasz, meaning “protector.”

Height: Dogs 28–30 inches (71–76 cm); bitches 26–28 inches (66–71 cm)

Weight: Dogs 100–115 pounds (45–52 kg); bitches 70–90 pounds (32–41 kg)

Coat type: Medium-length, straight or wavy; thick undercoat

Color: White (over dark skin)

Life span: 10–12 years

The Kuvasz is a highly intelligent dog that is fiercely protective and intensely loyal, yet somewhat aloof or independent, particularly with strangers. Kuvaszok are somewhat prone to hip dysplasia, and this breed may drool. Recognized in North America by the American Kennel Club and the United Kennel Club.

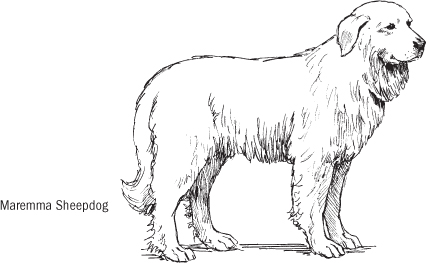

Origin: The Maremma region of Tuscany in Italy

Name in native land: Maremma (pronounced mair-emma), Abruzzese, Mareemmano-Abruzzese, Cane da Pastore (“sheepdog”)

Height: 23.5–28.5 inches (60–72 cm)

Weight: 65–110 pounds (29–50 kg)

Coat type: Long, harsh, double coat; outer coat straight or slightly wavy

Color: White with ivory, light yellow, or pale orange on the ears

Life span: 10–12 years

Descriptions of sheepdogs similar to the Maremma can be found in ancient Roman literature, and depictions can be seen in fifteenth-century paintings. Although Maremmas were developed to guard sheep and goats, cattle ranchers have found that they bond well with cows, and Maremmas are now being used to protect range cattle. A Maremma named Oddball was recently trained to guard the endangered penguin population on Middle Island in Warrnambool, Australia. The breed is recognized in North America by both the American Kennel Club and the United Kennel Club.

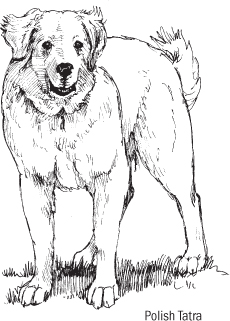

Origin: The Podhale section of Tatra region of the Carpathian Mountains in the south of Poland

Name in native land: Polski Owczarek Podhalanski

Height: Dogs 26–29 inches (66–74 cm); bitches 24–26 inches (61–66 cm)

Weight: 80–150 pounds (36–68 kg)

Coat type: Heavy double-coated; top coat straight or slightly wavy and hard to the touch; profuse, dense undercoat

Color: White over dark skin

Life span: 10–12 years

Tatras are strong, hardy guardian dogs developed to withstand cold, harsh temperatures as well as hot, dry heat. They are courageous; alert; and agile, swift runners. They are also independent, self-thinking, highly intelligent, and able to assess situations without human guidance. These dogs have been known to deter wolves and bears. Occasional cases of hip dysplasia occur. This uncommon breed is recognized by the United Kennel Club.