JUST A FEW months before Jefferson staged his historic dinner party, something happened in the Congress of the United States that no one had anticipated; indeed, most of the political leadership considered it an embarrassing intrusion. On February 11, 1790, two Quaker delegations, one from New York and the other from Philadelphia, presented petitions to the House calling for the federal government to put an immediate end to the African slave trade. This was considered an awkward interruption, disrupting as it did the critical debate over the assumption and residency questions with an inflammatory proposal that several southern representatives immediately denounced as mischievous meddling. Representative James Jackson from Georgia was positively apoplectic that such a petition would even be considered by any serious deliberative body. The Quakers, he argued, were infamous innocents incessantly disposed to drip their precious purity like holy water over everyone else’s sins. They were also highly questionable patriots, having sat out the recent war against British tyranny in deference to their cherished consciences. What standing could such dedicated pacifists enjoy among veterans of the Revolution, who, as Jackson put it, “at the risk of their lives and fortunes, secured to the community their liberty and property?”1

William Loughton Smith from South Carolina rose to second Jackson’s objection. The problematic patriotism of the Quaker petitioners was, Smith agreed, reprehensible. But his colleague from Georgia need not dally over the credentials of these pathetic eccentrics. The Constitution of the United States, only recently ratified, specifically prohibited the Congress from passing any law that abolished or restricted the slave trade until 1808. (Article 1, Section 9, paragraph 1, read: “The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight.”) Several current members of Congress also happened to have served as delegates to the Constitutional Convention, and they could all testify that the document would never have been approved in Philadelphia or ratified by several of the southern states without this provision. Beyond these still warm memories, the language of the Constitution was unambiguous: The federal government could not tamper with the slave trade during the first twenty years of the nation’s existence. The Quaker petitioners, therefore, were asking for something that had already been declared unavailable.2

Jackson, however, was not about to be consoled by constitutional protections. He detected even more sinister motives behind the benign smiles of the misnamed Society of Friends. “I apprehend, if through the interference of the general government, the slave-trade was abolished,” he observed, “it would evince to the people a general disposition toward a total emancipation.” In short, the Quaker petition for an end of the slave trade was really a stalking horse for a more radical and thoroughgoing scheme to end the institution of slavery itself.

James Madison rose to assume his customary role as the vigilant voice of cool reason. His colleague from Georgia was overreacting. Indeed, his impassioned rhetoric, while doubtless sincere, was both misguided and counterproductive. The Quaker petition should be heard and forwarded to a committee “as a matter of course.” If, in other words, the matter were treated routinely and with a minimum of fuss, it would quickly evaporate. As Madison put it, “no notice would be taken it out of doors.” On the other hand, Jackson’s own overwrought opposition, much like airbursts in a night battle, actually called attention to the issues the Quakers wished to raise. If Jackson would only restrain himself, the petition would go away and “never be blown up into a decision of the question respecting the discouragement of the African slave-trade, nor alarm the owners with an apprehension that the general government were about to abolish slavery in all the states.” For, as Madison assured Jackson, “such things are not contemplated by any gentlemen in the congress.”3

The next day, however, on February 12, Jackson’s fearful prophecies seemed to be coming true. For on that day another petition arrived in the House, this one from the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. It urged the Congress to “take such measures in their wisdom, as the powers with which they are invested will authorize, for promoting the abolition of slavery, and discouraging every species of traffic in slaves.” Just as Jackson had warned, opposition to the slave trade was now being linked to ending slavery altogether. What’s more, this new petition made two additional points calculated to exacerbate the fears of men like Jackson: First, it claimed that both slavery and the slave trade were incompatible with the values for which the American Revolution had been fought, and it even instructed the Congress on its political obligation to “devise means for removing this inconsistency from the Character of the American people.” Second, it challenged the claim that the Constitution prohibited any legislation by the federal government against the slave trade for twenty years, suggesting instead that the “general welfare” clause of the Constitution empowered the Congress to take whatever action it deemed “necessary and proper” to eliminate the stigma of traffic in human beings and to “Countenance the Restoration of Liberty for all Negroes.” Finally, to top it all off and heighten its dramatic appeal, the petition arrived under the signature of Benjamin Franklin, whose patriotic credentials and international reputation were beyond dispute. Indeed, if there were an American pantheon, only Washington would have had a more secure place in it than Franklin.4

Franklin’s endorsement of the petition from the Pennsylvania Abolition Society effectively assured that the preferred Madisonian strategy—calmly receiving these requests, then banishing them to the congressional version of oblivion—was not going to work. In fact, the ongoing debate on the assumption and residency questions was set aside for the entire day as the House put itself into committee of the whole to permit unencumbered debate on the petitions. During the course of that debate, which lasted between four and six hours, things were said that had never before been uttered in any public forum at the national level.

Granted, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had engaged in extensive debates about the slave trade and how to count slaves for the purposes of representation and taxation. But these debates had all occurred behind closed doors and under the strictest code of confidentiality. (Madison’s informal record of these debates, the fullest account, was not published in his lifetime.) Granted also that the place of slavery in the new national order had come up in several state ratifying conventions in 1788. But these state-based deliberations quite naturally tended to focus on local or regional interpretations of the Constitution’s rather elliptical handling of the forbidden subject. (No specific mention of “slavery,” “slaves,” or “Negroes” had been permitted into the final draft of the document.) If political leaders who had pushed through the constitutional settlement of 1787–1788 had been permitted to speak, their somewhat awkward conclusion would have been that slavery was too important and controversial a subject to talk about publicly.5

This explains the initial reaction of several representatives from South Carolina, who objected to the suggestion that the petitions should be read aloud in the halls of Congress. Aedanus Burke, for example, warned that the petitioners were “blowing the trumpet of sedition” and demanded that the galleries be cleared of all spectators and newspaper reporters. Jackson also heard trumpets blowing, though for him they were “trumpets of civil war.” The position of all the speakers from the Deep South seemed to be that the Constitution not only prohibited the Congress from legislating about slavery or the slave trade; it forbade anyone in Congress from even mentioning those subjects publicly. If this was their position, events quickly demonstrated that it was an argument they were destined to lose.6

THE DEBATE began when Thomas Scott of Pennsylvania, speaking on behalf of the petitioners, acknowledged that the Constitution imposed restrictions on Congress’s power to end the slave trade but said nothing whatsoever about abolishing slavery itself. As Scott put it, “if I was one of the judges of the United States, I do not know how far I might go if these people were to come before me and claim their emancipation, but I am sure I would go as far as I could.” Whereupon Jackson commented that any judge rendering such an opinion in Georgia “would be of short duration.”7

Jackson then launched into a sermon on God’s will, which he described as patently proslavery, based on several passages in the Bible and the pronouncements of every Christian minister in Georgia. Alongside the clear preferences of the Almighty, there was the nearly unanimous opinion of every respectable citizen in his state, whose livelihood depended on the availability of slave labor and who shared the elemental recognition, as Jackson put it, “that rice cannot be brought to market without these people.” William Loughton Smith preferred to leave the interpretation of God’s will to others, but he seconded the opinion of his colleague from Georgia that slavery was an economic precondition for the prosperity of his constituents, noting that “such is the state of agriculture in that country, no white man would perform the tasks required to drain the swamps and clear the land, so that without slaves it must be depopulated.”8

Smith also led the debate on behalf of the Deep South on that other great text, which was not the Bible but the Constitution. In Smith’s version of the story, the framers of the Constitution had recognized that the chief source of conflict among the state delegations was between those dependent on slave labor and those free of such dependency. A sectional understanding had emerged whereby northern states had agreed not to tamper with the property rights of southern states. In addition to the specific provisions of the Constitution, which recognized the slave population as worthy of at least some measure of representation in Congress and the protection of the slave trade for at least another twenty years after ratification, there was also an implicit but broadly shared understanding that the newly created federal government could do nothing to interfere with the existence of slavery in the South. All the southern states had ratified the Constitution with that understanding as a primal precondition: “Upon that reason they acceded to the Constitution,” Smith declared. “Unless that part was granted they would not [have] come into the union.” His evident distress at these Quaker petitions was rooted in his belief that the current debate represented a violation of that understanding.9

Representative Abraham Baldwin of Georgia chimed in to support Smith’s version of the federal compact. “Gentlemen who had been present at the formation of this Constitution”—Baldwin himself had been one such gentleman—“could not avoid the recollection of the pain and difficulty which the subject caused in that body.” The essential agreement reached at Philadelphia in 1787, Baldwin claimed, was the decision to remove slavery in the southern states from any influence by the northern states. “If gentlemen look over the footsteps of that body,” Baldwin observed, “they will find the greatest degree of caution used to imprint them, so as not to be easily eradicated.” Any attempt to renegotiate that sectional agreement by the current Congress would result in the disintegration of the national confederation at the very moment of its birth.10

Several northern representatives rose to contest the claim that both the Bible and the Constitution endorsed slavery. John Laurance of New York wondered how any Christian could read the Sermon on the Mount and believe it was compatible with chattel slavery. As far as the Constitution was concerned, Laurance acknowledged that certain provisions recognized the existence of slavery and provided temporary protection for those states wishing to import more Africans. But the larger understanding, as Laurance saw it, was that slavery was an anomaly in the American republic, a condition that could be tolerated in the short run precisely because there was a clear consensus that it would be ended in the long run. Scott of Pennsylvania echoed those sentiments, suggesting that the defining text was not the Constitution but the Declaration of Independence, which clearly announced that it was “not possible that one man should have property in person of another.”11

Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts attempted to offer conciliatory words to his southern colleagues, though he did so in a decidedly northern accent. His rambling remarks described the predicament of slave owners as truly tragic and not of their own making. They had been “betrayed into the slave-trade by the first settlers.” But rather than countenance their unfortunate condition, the chief task of those northern states spared the same fate should be to rescue them from it. This was both a political obligation and a “matter of humanity” toward both the slaves and those who owned them. The Quaker petitions were therefore not treasonable or out of order. They were “as worthy as anything that can come before the house.” Gerry then presented his own personal estimate of the revenue required to compensate the slave owners for purchasing their slaves at current market value and came up with the figure of $10 million. How he derived this amount was murky—it was much lower than any realistic estimate—but his thinking about the source for the revenue was clear: Voters would not accept a tax sufficient to cover these costs, so the only plausible course would be to establish a national fund for this purpose created out of the profits from the sale of western lands. As for the slave trade, the sooner that despicable traffic was ended, the better for everybody.12

Although the sectional battle lines were clearly drawn in the debate, the position of the Virginia delegation was equivocal. Representative John Page, for example, seemed to offer one of the most ringing endorsements of the petitions. He warned his colleagues from the Deep South that their opposition to the mere mention of an end to slavery and the slave trade was misguided. The real threat was silence. But then Page explained his thinking, which went like this: Reports of this debate would eventually find their way into the slave quarters of the South, and when the slaves learned that Congress would not even consider ways to mitigate their condition or end their misery, they would have no hope. The consequence would be slave insurrections, for “if anything could induce him [a slave] to rebel, it must be a stroke like this.”13

Madison’s thinking was decidedly less eccentric, although still problematic. As befitted the central player in the Constitutional Convention, Madison emphasized the various legal obligations imposed by the compact of 1787. While he thought the Constitution was crystal clear that Congress could not restrict or terminate the slave trade before 1808, it did not prohibit the members of the House from talking about the issue. They could talk about anything they wished, including the gradual abolition of slavery itself, though he felt that Congress was unlikely to take any dramatic action “tending to the emancipation of the slaves.” It could, however, opt to “make some regulation respecting the introduction of them [slaves] in the new states, to be formed out of the Western Territory,” a matter he thought “well worthy of consideration.” On the all-important question of the implicit understanding about the future of slavery itself, whether it was presumed to be on the road to extinction or forever protected where it already existed, Madison did not comment.14

Given the sharp sectional divisions in the debate, the vote to refer the petitions to a committee was surprisingly one-sided, 43 to 11; seven of the negative votes came from South Carolina and Georgia. Nor was anyone from either of those two states willing to serve on the committee, which was instructed to report its findings to the full House before the end of the session. Thus ended, at least for the time being, the fullest public exchange of views on the most deep-rooted problem facing the new American republic.15

HINDSIGHT PERMITS us to listen to the debate of 1790 with knowledge that none of the participants possessed. For we know full well what they could perceive dimly, if at all—namely, that slavery would become the central and defining problem for the next seventy years of American history; that the inability to take decisive action against slavery in the decades immediately following the Revolution permitted the size of the enslaved population to grow exponentially and the legal and political institutions of the developing U.S. government to become entwined in compromises with slavery’s persistence; and that eventually over 600,000 Americans would die in the nation’s bloodiest war to resolve the crisis, a trauma generating social shock waves that would reverberate for at least another century.

What is familiar history for us, however, was still the unknown future for them. And while the debate of 1790 reveals that they were profoundly interested in what the future would bring, their arguments were rooted in the past they knew best, which is to say, the recent experience of the successful revolutionary struggle against Great Britain and the even more recent creation of a federal government uniting the thirteen states into a more cohesive nation. The core of the disagreement in the debate of 1790 revolved around different versions of what has come to be called America’s “original intentions,” more specifically what the Revolution meant for the institution of slavery. One’s answer, it turned out, depended a great deal on which founding moment, 1776 or 1787, seemed most seminal. And it depended almost entirely on the geographic and demographic location of the person posing the question.

At least at the rhetorical level, the egalitarian principles on which the American revolutionaries had based their war for independence from Great Britain placed slavery on the permanent defensive and gave what seemed at the time a decisive advantage to the antislavery side of any debate. Jefferson’s initial draft of the Declaration of Independence had included language that described the slave trade as the perverse plot of an evil English monarch designed to contaminate innocent colonists. Though the passage was deleted by the Continental Congress in the final draft, it nevertheless captured the nearly rhapsodic sense that the American Revolution was both a triumphant and transformative moment in world history, when all laws and human relationships dependent on coercion would be swept away forever. And however utopian and excessive the natural rights section of the Declaration (“We hold these truths to be self-evident”) might appear later on, in the crucible of the revolutionary moment it gave lyrical expression to a widespread belief that a general emancipation of slaves was both imminent and inevitable, the natural consequence and fitting capstone of a glorious liberation from medieval mores historically associated with the very British government that Americans were rejecting. If the Bible were a somewhat contradictory source when it came to the question of slavery, the Declaration of Independence, the secular version of American scripture, was an unambiguous tract for abolition.16

In the long run, as we know, the liberal values of the Declaration did indeed win out. But we also need to recognize that in the short run, during and immediately after the war for independence, there was a prevailing consensus that slavery was already on the road to extinction. In 1776, for example, when the Continental Congress voted to repeal the nonimportation agreement of 1774, it chose to retain its prohibition against the importation of African slaves, a clear statement of opposition to the resumption of the slave trade. The manpower needs created by the six-year war generated several emancipation schemes whereby slaves would be freed and their owners compensated in return for enlistment for the duration of the conflict. Though this was really an emergency proposal dictated by the military crisis, and was ultimately rejected by the planter class in South Carolina and Georgia, its very suggestion seemed prophetic. Toward the end of the war, Lafayette, that paragon of the Franco-American alliance who was always eager to join the parade when history was on the march, urged Washington to declare a general emancipation for all slaves in Virginia and resettle them in the western region of the state as tenant farmers.17

But these were merely inspirational episodes that never quite lived up to their promise. The most tangible and enduring antislavery effects of the revolutionary mentality occurred in the northern states during and immediately after the war. Vermont (1777) and New Hampshire (1779) made slavery illegal in their state constitutions. Massachusetts declared it unconstitutional in a state Supreme Court decision (1783). Pennsylvania (1780) and Rhode Island (1784) passed laws ending it immediately within their borders. Connecticut (1784) followed suit with a gradual emancipation plan. New York and New Jersey, which contained the largest slave populations north of the Chesapeake, proved more recalcitrant for that very reason. But despite the defeat there of several gradual emancipation schemes in the 1780s, defenders of slavery in the northern states were clearly fighting a losing battle; abolition in the North was more a question of when than whether.18

Nor was this all. In 1782 the Virginia legislature passed a law permitting slave owners to free their slaves at their own discretion. By the end of the decade, there were over twelve thousand freedmen in the state. At the same time, Thomas Jefferson was writing Notes on the State of Virginia, the only book he ever published, in which he sketched out a plan whereby all slaves born after 1800 would eventually become free. In 1784 Jefferson also proposed a bill in the federal Congress prohibiting slavery in all the western territories; it failed to pass by a single vote. One did not need to be a hopeless visionary to conjure up a mental picture of the American Revolution as a dramatic explosion that had destroyed the very foundation on which slavery rested and then radiated out its emancipatory energies with irresistible force: The slave trade was generally recognized as a criminal activity; slavery was dead or dying throughout the northern states; the expansion of the institution into the West looked uncertain; Virginia appeared to be the beachhead for an antislavery impulse destined to sweep through the South; the time seemed ripe to reconcile America’s republican rhetoric with a new postrevolutionary reality.19

This uplifting vision, it turned out, was mostly a mirage. In fact, the very presumptiveness of the revolutionary rhetoric served to obfuscate the quite palpable reality that slavery, no matter how anomalous in purely ideological terms, was still deeply imbedded in the very structure of American society at multiple levels or layers that remained impervious to wishful thinking and revolutionary expectations.

The passionate conviction that the Revolution was like a mighty wave fated to sweep slavery off the American landscape actually created false optimism and fostered a misguided sense of inevitability that rendered human action or agency superfluous. (Why bother with specific schemes when history would soon arrive with all the answers?) Moreover, one of the reasons the Revolution proved so successful as a movement for independence was that its immediate and short-run goals were primarily political: removing royal governors and rewriting state constitutions that, in fact, already embodied many of the republican features the Revolution now sanctioned. Removing slavery, however, was not like removing British officials or revising constitutions. In isolated pockets of New York and New Jersey, and more panoramically in the entire region south of the Potomac, slavery was woven into the fabric of American society in ways that defied appeals to logic or morality. It also enjoyed the protection of one of the Revolution’s most potent legacies, the right to dispose of one’s property without arbitrary interference from others, especially when the others resided far away or claimed the authority of some distant government. There were, to be sure, radical implications latent in the “principles of ’76” capable of challenging privileged appeals to property rights, but the secret of their success lay in their latency—that is, the gradual and surreptitious ways they revealed their egalitarian implications over the course of the nineteenth century. If slavery’s cancerous growth was to be arrested and the dangerous malignancy removed, it demanded immediate surgery. The radical implications of the revolutionary legacy were no help at all so long as they remained only implications.20

The depth and apparent intractability of the problem became much clearer during the debates surrounding the drafting and ratification of the Constitution. Although the final draft of the document was conspicuously silent on slavery, the subject itself haunted the closed-door debates. No less a source than Madison believed that slavery was the central cause of the most elemental division in the Constitutional Convention: “the States were divided into different interests not by their difference of size,” Madison observed, “but principally from their having or not having slaves.… It did not lie between the large and small States: it lay between the Northern and Southern.”21

The delegates from New England and most of the Middle Atlantic states drew directly on the inspirational rhetoric of the revolutionary legacy to argue that slavery was inherently incompatible with the republican values on which the American Revolution had been based. They wanted an immediate end to the slave trade, an explicit statement prohibiting the expansion of slavery into the western territories as a condition for admission into the union, and the adoption of a national plan for gradual emancipation analogous to those state plans already adopted in the North. The most forceful expression of the northern position on the slave trade came, somewhat ironically, from Luther Martin of Maryland, who denounced it as “an odious bargain with sin” that was “inconsistent with the principles of the revolution and dishonorable to the American character.” The fullest expression of the northern position on abolition itself came from Gouverneur Morris, a New Yorker, but serving as a delegate from Pennsylvania, who described slavery as “a curse” that actually retarded the economic development of the South and “the most prominent feature in the aristocratic countenance of the proposed Constitution.” Morris even proposed a national tax to compensate the slave owners, claiming that he would much prefer “a tax for paying for all the Negroes in the United States than saddle posterity with such a Constitution.” In the speeches of Martin and Morris one can discern the clearest articulation of the view, later embraced by the leadership of the abolitionist movement, that slavery was a nonnegotiable issue; that this was the appropriate and propitious moment to place it on the road to ultimate extinction; and that any compromise of that long-term goal was a “covenant with death.”22

The southern position might more accurately be described as “deep southern,” since it did not include Virginia. Its major advocates were South Carolina and Georgia, and the chief burden for making the case in the Constitutional Convention fell almost entirely on the South Carolina delegation. The underlying assumption of this position was most openly acknowledged by Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina—namely, that “South Carolina and Georgia cannot do without slaves.” What those from the Deep South wanted was open-ended access to African imports to stock their plantations. They also wanted equivalently open access to western lands, meaning no federal restrictions on slavery in the territories. Finally, they wanted a specific provision in the Constitution that would prohibit any federal legislation restricting the property rights of slave owners—in effect, a constitutional assurance that slavery as it existed in the Deep South would be permitted to flourish. The clearest statement of their concerns came from Pierce Butler and John Rutledge of South Carolina. Butler explained that “the security the southern states want is that their Negroes may not be taken from them.” Rutledge added that “the people of those States will never be such fools as to give up so important an interest.” The implicit but unmistakably clear message underlying their position, which later became the trump card played by the next generation of South Carolinians in the Nullification Crisis in 1832, then more defiantly by the secessionists in 1861, was the threat to leave the union if the federal government ever attempted to implement a national emancipation policy.23

Neither side got what it wanted at Philadelphia in 1787. The Constitution contained no provision that committed the newly created federal government to a policy of gradual emancipation, or in any clear sense placed slavery on the road to ultimate extinction. On the other hand, the Constitution contained no provisions that specifically sanctioned slavery as a permanent and protected institution south of the Potomac or anywhere else. The distinguishing feature of the document when it came to slavery was its evasiveness. It was neither a “contract with abolition” nor a “covenant with death,” but rather a prudent exercise in ambiguity. The circumlocutions required to place a chronological limit on the slave trade or to count slaves as three-fifths of a person for purposes of representation in the House, all without ever using the forbidden word, capture the intentionally elusive ethos of the Constitution. The underlying reason for this calculated orchestration of non-commitment was obvious: Any clear resolution of the slavery question one way or the other rendered ratification of the Constitution virtually impossible.

Two specific compromises illustrate the tendency to fashion political bargains on slavery that simultaneously disguised the deep moral division within the Convention and framed the compromise solution in terms that permitted each side to claim victory. The first enigmatic bargain concerned the expansion of slavery into the West and actually occurred in the Confederation Congress that was also meeting in Philadelphia. One of the last and most consequential acts of the Congress was to pass the Northwest Ordinance in July of 1787. Article Six of the ordinance forbade slavery in the territory north of the Ohio River, a decision that could plausibly be interpreted as the first step toward a more general exclusion of slavery in all incoming states (the Jefferson proposal of 1784). On the other hand, the ordinance could also be read as a tacit endorsement of slavery in the southwestern region (which eventually proved to be the case). In any event, the passage of the Northwest Ordinance was a blessed event for the delegates at the Constitutional Convention, in part because it removed a potentially divisive issue from their agenda, and in part because the solution it posed could be heard to speak with both a northern and southern accent.24

The second bargain can, with considerable justice, be described as the most important compromise reached at the Constitutional Convention, even more so than the “Great Compromise” between large and small states over representation in the Senate and House. It might more accurately be called the “Sectional Compromise.” No less an authority than Madison considered it the most consequential of all the secret deals made in Philadelphia: “An understanding on the two subjects of navigation and slavery,” Madison explained, “had taken place between those parts of the Union.” The bargain entailed an exchange of votes whereby New England agreed to back an extension of the slave trade for twenty years in return for support from the Deep South for making the federal regulation of commerce a mere majority vote in the Congress rather than a supermajority of two-thirds. As with the Northwest Ordinance, both sides could declare victory; and the true victors would only become known with the passage of time. (John C. Calhoun would subsequently conclude that if the Deep South had regarded this bargain as a wager on the future, it was a losing bet.)25

The debates in the ratifying conventions of the respective states only exposed the irreconcilable differences of opinion that the Constitution had so deftly bundled together. In Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, for example, opponents of the Constitution objected to the implicit acceptance of slavery’s persistence, represented by the three-fifths clause and the twenty-year extension of the slave trade. Supporters assured them, however, that these partial and limited concessions only reflected the fading gasps of a dying institution. James Wilson of Pennsylvania predicted that emancipation was inevitable “and though the period is more distant than I could wish, yet it will produce the same kind of gradual change for the whole nation as was pursued in Pennsylvania.” As for the western territories, Wilson was certain that Congress “would never allow slaves in any of the new states.” Luther Martin, on the other hand, came out against the Constitution on the grounds that the protections afforded slavery “render us contemptible to every true friend of liberty in the world.” Martin was perhaps the first public advocate of the “covenant with death” interpretation of the Constitution, as well as the first former delegate to denounce the Sectional Compromise as a corrupt bargain. But in a close vote, his Maryland colleagues rejected his reading of the document as excessively pessimistic.26

Meanwhile, down in South Carolina the assurances afforded slavery that so troubled Martin of Maryland struck many delegates as inadequate. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney helped win the day for ratification with his own gloss on the true meaning of the compact:

We have a security that the general government can never emancipate them, for no such authority is granted and it is admitted, on all hands, that the general government has no powers but which are expressly granted by the Constitution, and that all rights not expressed were reserved by the several states.… In short, considering all circumstances, we have made the best terms for the security of this species of property it was in our power to make. We would have made better if we could; but on the whole, I do not think them bad.27

The fullest and most intellectually interesting debate occurred in Virginia. As the most populous state with both the largest slave population (292,000) and the largest free-black population (12,000), Virginia’s demographic profile looked decidedly southern. Only South Carolina had a higher density of blacks (60 percent to Virginia’s 40 percent). But Virginia’s rhetorical posture sounded distinctly northern; or perhaps more accurately, the political leadership of the Old Dominion relished its role as the chief spokesman for “the principles of ’76,” which placed slavery under a permanent shadow and seemed to align Virginia against the Deep South. Jefferson, it must be remembered, had proposed the abolition of slavery in all the western territories. Madison, though he eventually endorsed the three-fifths clause, acknowledged his discomfort with the doctrine, confessing that “it may appear to be a little strained in some points.” Most significantly, the Virginians were adamantly opposed to the continuation of the slave trade. Both Madison and his colleague George Mason denounced the Sectional Compromise in the Constitutional Convention that prolonged the trade; and Mason eventually voted against ratification in part for that very reason. On the surface, at least, Virginia seemed the one southern state where the ideological contagion of the American Revolution remained sufficiently potent to dissolve the legacy of slavery.28

Upon closer examination, however, Virginia turned out to resemble the fuzzier and more equivocal picture that best describes the nation at large and that the Constitution was designed to mirror. For beneath their apparent commitment to antislavery and their accustomed place in the vanguard of revolutionary principles, the Virginians were overwhelmingly opposed to relinquishing one iota of control over their own slave population to any federal authority. Whether they were living a paradox or a lie is an interesting question. What is undeniably clear is that the Virginia leadership found itself in the peculiar position of acknowledging that slavery was an evil and then proceeding to insist that there was nothing the federal government could do about it. Mason’s vehement opposition to the slave trade rested cheek by jowl with his demand for a constitutional guarantee to protect what he described as “the property of that kind which we have already.”

Virginia’s true position was less principled than it looked. Its plantations were already stocked with slaves, so opposition to the slave trade made economic sense, as did opposition to emancipation. Mason thought that the Constitution had it exactly wrong: “they have done what they ought not to have done”—that is, extended the life of the slave trade—“and have left undone what they ought to have done”—that is, explicitly prohibited federal interference in what he called “our domestic interests.” Edmund Randolph made it abundantly clear at the Virginia ratifying convention just what “domestic interests” Mason had in mind. Randolph in his own roundabout way had come over to support ratification, so he needed to counter Mason’s apprehensions about slavery. “I might tell you,” he apprised his Virginia colleagues, “that the Southern States, even South Carolina herself, conceived this property to be secure,”and that except for Mason “not a member of the Virginia delegation had the smallest suspicion of the abolition of slavery.” Virginia, in short, talked northern but thought southern.29

IF ONE WISHED to generalize, then, about the situation that obtained in 1790 at the moment of the congressional debate over the Quaker petitions, the one thing that seemed clear concerning slavery was that nothing was clear at all. The initial debate in February had, in fact, accurately reflected the competing and incompatible presumptions about slavery’s fate in the American republic, with one side emphasizing the promissory note to end it purportedly issued in 1776, the other side emphasizing the gentlemen’s agreement to permit it reached in 1787, and a middle group, dominated by the Virginians, straddling both sides and counseling moderation lest the disagreement produce a sectional rupture. Both sides could plausibly claim a core strand of the revolutionary legacy as their own. And all parties to the debate seemed to believe that history, as well as the future, was on their side.

Like a lightning flash in the night, the initial exchange on the floor of Congress in February of 1790 had exposed these divisions of opinion before a national audience for the first time. On March 8 the committee was prepared to submit its report, thereby assuring that the controversy would not go away or get buried in some parliamentary graveyard. Representatives from the Deep South rose to express their outrage that the forbidden subject was again being allowed into public view. William Loughton Smith pointed up to the antislavery advocates who had stacked the galleries “like evil spirits hovering over our heads.” James Jackson actually made menacing faces at the Quakers in the gallery, called them outright lunatics, then launched into a tirade so emotional and incoherent that reporters in the audience had difficulty recording his words. The gist seemed to be that any decision to receive the committee report was tantamount to the dissolution of the union.30

These threatening harangues managed to delay matters, but the Deep South lacked the votes. On March 16 the committee was ready to make its report to the House. First Jackson and then Smith were also prepared with their response, which turned out to be the fullest public exposition of the proslavery position yet presented in the United States. In fact, virtually every argument that southern defenders of slavery would mount during the next seventy years of the national controversy, right up to the eve of the Civil War, came gushing forth over the next two days.31

Jackson spoke first and held the floor for about two hours. He could not believe that a dignified body of sober-minded legislators were allowing these “shaking Quakers” with their throbbing consciences to control the national agenda. One of the petitioners, an infamous do-gooder of uncertain sanity named Warner Mifflin, had actually acknowledged that his antislavery vision had come to him after he was struck by lightning in a thunderstorm. The Congress had been elected to steer the ship of state through rough and uncharted waters, not to take aboard a crew of dazed dreamers bent on sailing to the Promised Land but inadvertently destined to sink the ship on its maiden voyage.

Speaking of promises, a “sacred compact” had been made when the nation was founded in 1787, “a compact which brought us together mutually to relinquish a share of our interests to preserve the remainder.” Then Jackson described the Sectional Compromise at the Constitutional Convention, whereby “the southern states for this very principle gave into what might be termed the navigation law of the eastern and western states,” a concession granted in return for retention of the slave trade for twenty years. The Quaker petitioners were now asking the Congress to break that compact and thereby violate the understanding on which the states of the Deep South had entered the union.

Moreover, there was an even more elemental understanding implicitly codified in Philadelphia but actually predating the Constitutional Convention by many years. It was rooted in the realistic recognition that slavery had been grafted onto the character of the southern states during the colonial era and had become a permanent part of American society south of the Potomac. “If it were a crime, as some assert but which I deny,” Jackson explained, “the British nation is answerable for it, and not the present inhabitants, who now hold that species of property in question.” Northern posturing on this matter was insufferable, as Jackson saw it, since their oozing arguments transformed a geographic accident and a product of historical circumstance into a willful sin. The incontrovertible truth was that slavery was “one of those habits established long before the Constitution, and could not now be remedied.” When the thirteen colonies rebelled against Britain, “no one raised this question.” And when the nation was formed into a more unified whole in 1787, “the Union had received them with all the ill habits about them.” The implicit but thoroughly understood sectional agreement, which the Sectional Compromise at Philadelphia merely underlined, was that slavery, while anomalous within the framework of republican ideology, was a self-evident reality that had been allowed to coexist alongside Jefferson’s self-evident truths. “The custom, the habit of slavery is established,” Jackson observed, and all responsible American statesmen had agreed that “the southern states must be left to themselves on this subject.” Antislavery idealists might prefer to live in some better world, which like all such places was too good to be true. The American nation in 1790, however, was a real world, laden with legacies like slavery, and therefore too true to be good. Jackson did not go so far as to argue, as did southern apologists two or three generations later, that slavery was “a positive good.” But he did insist, in nonnegotiable language, that it was “a necessary evil.”

Jackson had several books at his side, and he began to read to his colleagues in order to demonstrate that his opinions were shared by the most respected authorities. The most respected authority of all, the Christian God in the Bible, sanctioned slavery in several passages from the Old Testament. In addition, the most reliable and recent studies of African tribal culture demonstrated that slavery was a long-standing custom among the Africans themselves, so enslaved Africans in America were simply experiencing a condition here that they would otherwise experience, probably in more oppressive fashion, in their mother country.

Then Jackson referred his colleagues to the opinions of “Mr. Jefferson, our secretary of state,” and began reading from Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia on the practical question: “What is to be done with the slaves when freed?” Either they must be incorporated where they are or they must be colonized somewhere else. Jefferson’s view of the question was so well known that Jackson claimed he could quote from Jefferson’s book from memory: The two races cannot live together on equal terms because of “deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites—ten thousand recollections by the blacks of the injuries they have sustained—new provocations—the real distinctions that nature has made, and many other circumstances which divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which would never end but with the extermination of one or the other race.” Perhaps there were a few whites in the North who did not concur with Mr. Jefferson’s sentiments. Perhaps the Quaker petitioners approved of racial mixing and looked forward to “giving their daughters to negro sons, and receiving the negro daughters for their sons.” But despite the relatively small size of the black population in the North, the pattern of racial segregation there suggested that most northern whites shared Jefferson’s belief that “incorporation” was unlikely. In the South, where the number of blacks was so much larger, it was unthinkable.

Those advocating emancipation, then, need to confront the intractable dilemma posed by the sheer size of an African population that, once freed, must be removed to some other location. Apart from the obvious question of cost, which would prove astronomically high, where could the freed blacks be sent? Those advocating an African solution might profitably study the recent English efforts to establish a black colony in Sierra Leone, where most of the freed blacks died or were enslaved by the local African tribes. Those advocating a location in the American West also needed to think again: “The peoples of America, like an overwhelming torrent, are rapidly covering the earth, and extending their settlements throughout this vast continent, nor is there any spot, however remote, but a short period will settle.” Moreover, vast tracts in the West had already been promised to the Indians, whose response to a population of black neighbors was likely to prove uncharitable in the extreme. If anyone had a responsible solution to this problem, Jackson claimed to be receptive. But until such a solution materialized, all talk of emancipation must cease.32

No one from outside the Deep South rose to answer Jackson. The next day, March 17, William Loughton Smith held the floor for over two hours without interruption and repeated most of Jackson’s points. Whereas Jackson tended toward a more volatile and pulpit-thumping style reminiscent of an itinerant Presbyterian minister in the revivalistic mode, Smith preferred the more measured cadences of the South Carolina aristocrat steeped in Ciceronian formalities. But despite the stylistic differences, the arguments were identical: The Constitution was absolutely clear that the slave trade could not be ended before 1808; there was a sectional compact that recognized slavery’s existence where it was already rooted south of the Potomac; any attempt to renegotiate that compact would mean the dissolution of the union; the demographic and racial realities rendered any emancipation scheme impossible, most especially for white southerners who lived amid a sizable black population. Smith also quoted from Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, then put his own cast on the racial implications of a large free-black population in America: “If the blacks did not intermarry with the whites, they would remain black until the end of time; for it was not contended that liberating them would whitewash them; if they did intermarry with the whites, then the white race would be extinct, and the American people would all be of the mulatto breed. In whatever light therefore the subject was viewed, the folly of emancipation was manifest.”33

The full proslavery argument was now out in the open. If one looked forward from this dramatic moment, the speeches by Jackson and Smith became prophetic previews of coming attractions for the southern defense of slavery in the nineteenth century, a defense that would eventually lose on the battlefields of the Civil War. If one looked backward, nothing quite so defiant or systematic had ever been presented before. True enough, the constitutional arguments represented a consolidation of points made in Philadelphia in 1787 and then in several state ratifying conventions. But the brazen claim that slavery must be accepted unconditionally as a permanent feature of the national confederation was, if not wholly new, at least an interpretive clarification never made before in a national forum. And the racial argument, which added the specter of a racially mixed American society as a consequence of emancipation, gave a new dimension to the debate by attempting to transform the sectional disagreement between North and South into a national alliance of whites against blacks.34

The novelty of the arguments now pouring forth from the representatives of the Deep South must also be understood in context. The particulars were new, but the attitudes on which they rested were familiar. No responsible statesman in the revolutionary era had ever contemplated, much less endorsed, a biracial American society. In 1776, for example, when the Continental Congress had commissioned John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson to design a seal for the United States, they produced a national emblem depicting Americans of English, Scottish, Irish, French, German, and Dutch extraction. There were no Africans or Native Americans in the picture. The new proslavery argument, then, drew on assumptions about the white Anglo-Saxon character of the emerging American nation that were latent but long-standing. No explicit articulation of those assumptions had been necessary in a national forum before 1790, because no frontal assault on slavery had been made that required a direct or systematic response.

Those historians who claim that a distinctive racial ideology first came into existence at this time, describing it as a fresh “construction” or “invention” designed to frame the debate over slavery in a more effectively prejudicial way, have a point, or perhaps half a point, in the sense that the challenge to slavery drove the racial (and racist) presumptions to the surface of the debate for the first time. But they had been lurking in the hearts and minds of the revolutionary generation all along. The ultimate legacy of the American Revolution on slavery was not an implicit compact that it be ended, or a gentlemen’s agreement between the two sections that it be tolerated, but rather a calculated obviousness that it not be talked about at all. Slavery was the unmentionable family secret, or the proverbial elephant in the middle of the room. What was truly new in the proslavery argument was not really the ideas or attitudes expressed, but the expression itself.35

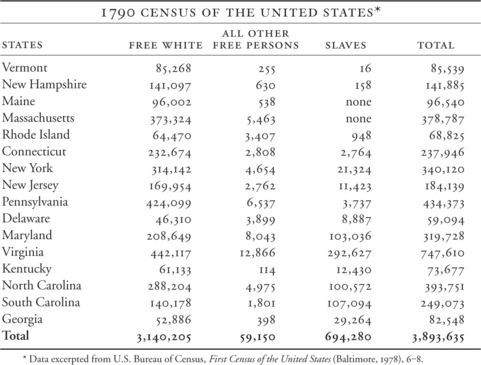

There was yet another new ingredient about to enter the debate in 1790, though it too was more a matter of making visible and self-conscious what had previously hovered in some twilight zone of hazy and unspoken recognition. Perhaps the least controversial decision of the First Congress was passage of legislation that authorized the census of 1790, an essential item because accurate population figures were necessary to determine the size of state delegations in the House. The following information was being gathered, quite literally, while the debate over the Quaker petitions raged:

At the most obvious level, these numbers confirmed with enhanced precision the self-evident reality that slavery was a sectional phenomenon that was dying out in the North and flourishing in the South. The exceptions were New York and New Jersey, which, not incidentally, remained the only northern states to resist the passage of gradual emancipation laws. In general, then, there was a direct and nearly perfect correlation between demography and ideology—that is, between the ratio of blacks to whites in the population and the reluctance to consider abolition. When the proslavery advocates of the Deep South unveiled their racial argument—What will happen between the races after emancipation?—the census of 1790 allowed one to predict the response with near precision. Wherever the black population reached a threshold level, slavery remained the preferred means of assuring the segregation of the races.

The only possible exception to this rule was the Upper South, to include the states of Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. There the slave populations were large, in Virginia very large indeed, but so were the populations of free blacks (“All Other Free Persons”). From a strictly demographic perspective, Virginia was almost as vulnerable to the specter of postemancipation racial fears as South Carolina, but the growing size of the free-black population accurately reflected the presence of multiple schemes for gradual emancipation within the planter class and the willingness of at least a few slave owners to act in accord with the undeniable logic of the American Revolution. The sheer size of Virginia’s total population, amplified by the daunting racial ratio, and then further amplified by the political prowess of its leadership at the national level, all combined to make it the key state. If any national plan for ending slavery was to succeed, Virginia needed to be in the vanguard.

Finally, the census of 1790 provided unmistakable evidence that those antislavery advocates who believed that the future was on their side were deluding themselves. For the total slave population was now approaching 700,000, up from about 500,000 in the year of the Declaration of Independence. Despite the temporary end of the slave trade during the war, and despite the steady march of abolition in the North, the slave population in the South was growing exponentially at the same exploding rate as the American population as a whole, which meant it was doubling every twenty to twenty-five years. Given the political realities that defined the parameters of any comprehensive program for emancipation—namely, compensation for owners, relocation of freed slaves, and implementation over a sufficient time span to permit economic and social adjustments—the larger the enslaved population grew, the more financially and politically impractical any emancipation scheme became. (One interpretation of the Deep South’s argument of 1790 was that, at least from their perspective, the numbers already made such a decision impossible.) The census of 1790 revealed that the window of opportunity to end slavery was not opening, but closing. For not only were the numbers becoming wholly unmanageable, but the further one got from 1776, the lower the revolutionary fires burned and the less imperative the logic of the revolutionary ideology seemed. What one historian has called “the perishability of revolutionary time” meant that the political will to act was also racing against the clock. In effect, the fading revolutionary ideology and the growing racial demography were converging to close off the political options. With all the advantage of hindsight, a persuasive case can be made that the Quaker petitioners were calling for decisive action against slavery at the last possible moment, if indeed there was such a moment, when gradual emancipation had any meaningful prospect for success.36

THE CHIEF strength of the proslavery argument that emerged from the Deep South delegation in the congressional debate of March 16–17 was its relentless focus on the impractical dimensions of all plans for abolition. In effect, their arguments exposed the two major weaknesses of the antislavery side: First, those ardent ideologues who believed that slavery would die a natural death after the Revolution were naïve utopians proven wrong by the stubborn realities reflected in the census of 1790; second, the gradual emancipation plans implemented in the northern states were inoperative models for the nation as a whole, because the northern states contained only about 10 percent of the slave population; for all those states from Maryland south, the cost of compensation and the logistical difficulties attendant upon the relocation of the freed slaves were simply insurmountable; the numbers, quite simply, did not work.

How correct were these conclusions? From a strictly historical perspective, we can never know the answer to that question. Since no one from the North or the Upper South rose to answer the delegation from the Deep South, and since no national plan for gradual emancipation ever came before the Congress for serious consideration, we are left with a great silence, which itself becomes the principal piece of historical evidence to interpret. And the two overlapping interpretations that then present themselves with irresistible logic are quite clear: First, the arguments of the Deep South were unanswerable because there was sufficient truth in the fatalistic diagnosis to persuade other members of the House that the slavery problem was intractable; and second, whatever shred of possibility still existed to take concerted action against slavery was overwhelmed by the secessionist threat from South Carolina and Georgia, since there could be no national solution to the slavery problem if there were no nation at hand to implement a solution. Perhaps, as some historians have argued, South Carolina and Georgia were bluffing. But the most salient historical fact cannot be avoided: No one stepped forward to call their bluff.

Though we might wish otherwise, the history of what might have been is usually not really history at all, mixing together as it does the messy tangle of past experience with the clairvoyant certainty of our present preferences. That said, even though no formal proposal for a gradual emancipation program came before the Congress in 1790, all the elements for such a program were present in the debates. Moreover, in March of 1790, while the congressional debate was raging, a prominent Virginian by the name of Fernando Fairfax drafted a “Plan for Liberating the Negroes within the United States,” which was subsequently published in Philadelphia the following December. Fairfax’s plan fleshed out the sketchy outline that Jefferson had provided in Notes on the State of Virginia. Another Virginian, St. George Tucker, developed an even fuller version of the same scheme six years later. In short, the historical record itself, and not just our own omniscient imaginations, provides the requisite evidence from which we can reconstruct the response to the proslavery argument. In so doing, we are not just engaging in wishful thinking, are not attempting to rewrite history along more attractive lines, but rather trying to assess the historical viability of a national emancipation policy in 1790. What chance, if any, existed at that propitious moment to put slavery on the road to extinction?37

All the plans for gradual emancipation assumed that slavery was a moral and economic problem that demanded a political solution. All also assumed that the solution needed to combine speed and slowness, meaning that the plan needed to be put into action quickly, before the burgeoning slave population rendered it irrelevant, but implemented gradually, so the costs could be absorbed more easily. Everyone advocating gradual emancipation also made two additional assumptions: First, that slave owners would be compensated, the funds coming from some combination of a national tax and from revenues generated by the sale of western lands; second, that the bulk of the freed slaves would be transported elsewhere, the Fairfax plan favoring an American colony in Africa on the British model of Sierra Leone, others proposing what might be called a “homelands” location in some unspecified region of the American West, and still others preferring a Caribbean destination.

As we have seen, the projected cost of compensation was a potent argument against gradual emancipation, and the argument has been echoed in most scholarly treatments of the topic ever since. Estimates vary according to the anticipated price for each freed slave, which ranges between one hundred and two hundred dollars. The higher figure produces a total cost of about $140 million to emancipate the entire slave population in 1790. Since the federal budget that year was less than $7 million, the critics seem to be right when they conclude that the costs were not just daunting but also prohibitively expensive. The more one thought about such numbers, in effect, the more one realized that further thought was futile. There is some evidence that reasoning of just this sort was going on in Jefferson’s mind at this time, changing him from an advocate of emancipation to a silent and fatalistic procrastinator.38

The flaw in such reasoning, however, would have been obvious to any accountant or investment banker with a modicum of Hamiltonian wisdom. For the chief virtue of a gradual approach was to extend the cost of compensation over several decades so that the full bill never landed at one time or even on one generation. In the scheme that St. George Tucker proposed, for example, purchases and payments would continue for the next century, delaying the arrival of complete emancipation, to be sure, but significantly reducing the impact of the current costs by spreading them into the distant future. The salient question in 1790 was not the total cost but, with an amortized debt, the initial cost of capitalizing a national fund (often called a “sinking fund”) for such purposes. The total debt inherited from the states and the federal government in 1790 was $77.1 million. A reasonable estimate of the additional costs for capitalizing a gradual emancipation program would have increased the national debt to about $125 million. While daunting, these numbers were not fiscally impossible. And they became more palatable when folded into a total debt package produced by a war for independence.39

The other major impediment, equally daunting as the compensation problem at first glance, even more so upon reflection, was the relocation of the freed slaves. Historians have not studied the feasibility of this feature as much as the compensation issue, preferring instead to focus on the racial prejudices that required its inclusion, apparently fearing that their very analysis of the problem might be construed as an endorsement of the racist and segregationist attitudes prevalent at the time. Two unpalatable but undeniable historical facts must be faced: First, that no emancipation plan without this feature stood the slightest chance of success; and second, that no model of a genuinely biracial society existed anywhere in the world at that time, nor had any existed in recorded history.40

The gradual emancipation schemes adopted in the northern states never needed to face this question squarely, because the black population there remained relatively small. South of the Potomac was a different matter altogether, since approximately 90 percent of the total black population resided there. Any national plan for gradual emancipation needed to transform this racial demography by relocating at least a significant portion of that population elsewhere. But where? The subsequent failure of the American Colonization Society and the combination of logistical and economic difficulties in the colony of Liberia exposed the impracticality of any mass migration back to Africa. The more viable option was transportation to the unsettled lands of the American West, along the lines of the Indian removal program adopted over forty years later. In 1790, however, despite the presumptive dreams of a continental empire, the Louisiana Purchase remained in the future and the vast trans-Mississippi region continued under Spanish ownership. While the creation of several black “homelands” or districts east of the Mississippi was not beyond contemplation—it was mentioned in private correspondence by a handful of antislavery advocates—it was just as difficult to envision then as it is difficult to digest now.41

More than the question of compensation, then, the relocation problem was perilously close to insoluble. To top it all off, and add yet another layer of armament to the institution of slavery, any comprehensive plan for gradual emancipation could only be launched at the national level under the auspices of a federal government fully empowered to act on behalf of the long-term interests of the nation as a whole. Much like Hamilton’s financial plan, any effective emancipation initiative conjured up fears of the much-dreaded “consolidation” that the Virginians, more than anyone else, found so threatening. (Indeed, for at least some of the Virginians, the deepest dread and greatest threat was that federal power would be used in precisely this way.) All the constitutional arguments against the excessive exercise of government power at the federal level then kicked in to make any effort to shape public policy more problematic.

Any attempt to take decisive action against slavery in 1790, given all these considerations, confronted great, perhaps impossible, odds. The prospects for success were remote at best. But then the prospects for victory against the most powerful army and navy in the world had been remote in 1776, as had the likelihood that thirteen separate and sovereign states would create a unified republican government in 1787. Great leadership had emerged in each previous instance to transform the improbable into the inevitable. Ending slavery was a challenge on the same gigantic scale as these earlier achievements. Whether even a heroic level of leadership stood any chance was uncertain because—and here was the cruelest irony—the effort to make the Revolution truly complete seemed diametrically opposed to remaining a united nation.

ONE PERSON stepped forward to answer the challenge, unquestionably the oldest, probably the wisest, member of the revolutionary generation. (In point of fact, he was actually a member of the preceding generation, the grandfather among the fathers.) Benjamin Franklin was very old and very ill in March of 1790. He had been a fixture on the American scene for so long and had outlived so many contemporaries—he had once traded anecdotes with Cotton Mather and was a contemporary of Jonathan Edwards—that reports of his imminent departure lacked credibility; his last act seemed destined to go on forever; he was an American immortal. If a twentieth-century photographer had managed to commandeer a time machine and travel back to record the historic scenes in the revolutionary era, Franklin would have been present in almost every picture: in Philadelphia during the Continental Congress and the signing of the Declaration of Independence; in Paris to draft the wartime treaty with France and then almost single-handedly (assist to John Adams) conclude the peace treaty with Great Britain; in Philadelphia again for the Constitutional Convention and the signing of the Constitution. Even without the benefit of photography, Franklin’s image—with its bemused smile, its bespectacled but twinkling eyes, its ever-bald head framed by gray hair flowing down to his shoulders—was more famous and familiar to the world than the face of any other American of the age.

What Voltaire was to France, Franklin was to America, the symbol of mankind’s triumphal arrival at modernity. (When the two great philosopher-kings embraced amid the assembled throngs of Paris, the scene created a sensation, as if the gods had landed on earth and declared the dawning of the Enlightenment.) The greatest American scientist, the most deft diplomat, the most accomplished prose stylist, the sharpest wit, Franklin defied all the categories by inhabiting them all with such distinction and nonchalant grace. Over a century before Horatio Alger, he had invented the role and called it Poor Richard, the original self-taught, homespun American with an uncanny knack for showing up where history was headed and striking a folksy pose that then dramatized the moment forever: holding the kite as the lightning struck; lounging alongside Jefferson and offering witty consolations as the Continental Congress edited out several of Jefferson’s most cherished passages; wearing a coonskin cap for his portrait in Paris; remarking as the delegates signed the Constitution that, yes, the sun that was carved into the chair at the front of the room did now seem to be rising.42

In addition to seeming eternal, ubiquitous, protean, and endlessly quotable, Franklin had the most sophisticated sense of timing among all the prominent statesmen of the revolutionary era. His forceful presence at the defining moment of 1776 had caused most observers to forget that, in truth, Franklin was a latecomer to the patriot cause, the man who had spent most of the 1760s in London attempting to obtain, of all things, a royal charter for Pennsylvania. He had actually lent his support to the Stamp Act in 1765 and lobbied for a position within the English government as late as 1771. But he had leapt back across the Atlantic and onto the American side of the imperial debate in the nick of time, a convert to the cause, who, by the dint of his international reputation, was quickly catapulted into the top echelon of the political leadership. Sent to France to negotiate a wartime alliance, he arrived in Paris just when the French ministry was ready to entertain such an idea. He remained in place long enough to lead the American delegation through the peace treaty with England, then relinquished his ministerial duties to Jefferson in 1784, just when all diplomatic initiatives on America’s behalf in Europe bogged down and proved futile. (When asked if he was Franklin’s replacement, Jefferson had allegedly replied that he was his successor, but that no one could replace him.) He arrived back in Philadelphia a conquering hero and in plenty of time to be selected as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.43

This gift of exquisite timing continued until the very end. In April of 1787, Franklin agreed to serve as the new president of the revitalized Pennsylvania Abolition Society and to make the antislavery cause the final project of his life. Almost sixty years earlier, in 1729, as a young printer in Philadelphia, he had begun publishing Quaker tracts against slavery and the slave trade. Throughout the middle years of the century and into the revolutionary era, he had lent his support to Anthony Benezet and other Quaker abolitionists, and he had spoken out on occasion against the claim that blacks were innately inferior or that racial categories were immutable. Nevertheless, while his antislavery credentials were clear, at one point Franklin had owned a few household slaves himself, and he had never made slavery a priority target or thrown the full weight of his enormous prestige against it.

Starting in 1787, that changed. At the Constitutional Convention he intended to introduce a proposal calling for the inclusion of a statement of principle, condemning both the slave trade and slavery, thereby making it unequivocally clear that the founding document of the new American nation committed the government to eventual emancipation. But several northern delegates, along with at least one officer in the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, persuaded him to withdraw his proposal on the grounds that it put the fragile Sectional Compromise, and therefore the Constitution itself, at risk. The petition submitted to the First Congress under his signature, then, was essentially the same proposal he had wanted to introduce at the Convention. With the Constitution now ratified and the new federal government safely in place, Franklin resumed his plea that slavery be declared incongruous with the revolutionary principles on which the nation was founded. The man with the impeccable timing was choosing to make the anomaly of slavery the last piece of advice he would offer his country.44

Though his health was declining rapidly, newspaper accounts of the proslavery speeches in the House roused him for one final appearance in print. Under the pseudonym “Historicus,” he published a parody of the speech delivered by James Jackson of Georgia. It was a vintage Franklin performance, reminiscent of his bemused but devastating recommendations to the English government in 1770 about the surest means to take the decisive action guaranteed to destroy the British Empire. This time, he claimed to have noticed the eerie similarity between Jackson’s speech on behalf of slavery and one delivered a century earlier by an Algerian pirate named Sidi Mehemet Ibrahim.

Surely the similarities were inadvertent, he suggested, since Jackson was obviously a virtuous man and thus incapable of plagiarism. But the arguments and the very language were identical, except that Jackson used Christianity to justify enslavement of the Africans, while the African used Islam to justify enslavement of Christians. “The Doctrine, that Plundering and Enslaving the Christians is unjust, is at best problematical,” the Algerian had allegedly written, and when presented with a petition to cease capturing Europeans, he had argued to the divan of Algiers “that it is in the Interest of the State to continue the Practice; therefore let the Petition be rejected.” All the same practical objections to ending slavery were also raised: “But who is to indemnify their Masters for the Loss? Will the State do it? Is our Treasury sufficient …? And if we set our Slaves free, what is to be done with them …? Our people will not pollute themselves by intermarrying with them.” Franklin then had the Algerian argue that the enslaved Christians were “better off with us, rather than remain in Europe where they would only cut each other’s throats in religious wars.” Franklin’s pointed parody was reprinted in several newspapers from Boston to Philadelphia, though nowhere south of the Potomac. It was his last public act. Three weeks later, on April 17, the founding grandfather finally went to his Maker.45

Prior to his passing, however, the great weight of Franklin’s unequivocal endorsement made itself felt in the congressional debate and emboldened several northern representatives to answer the proslavery arguments of the Deep South with newfound courage. Franklin’s reputation served as the catalyst in an exchange, as Smith of South Carolina attempted to discredit his views by observing that “even great men have their senile moments.” This prompted rebuttals from the Pennsylvania delegation: “Instead of proving him superannuated,” Franklin’s antislavery views showed that “the qualities of his soul, as well as those of his mind, are yet in their vigour”; only Franklin still seemed able “to speak the language of America, and to call us back to our first principles”; critics of Franklin, it was suggested, only exposed the absurdity of the proslavery position, revealing clearly that “an advocate for slavery, in its fullest latitude, at this stage of the world, and on the floor of the American Congress too, is a phenomenon in politics.… They defy, yea, mock all belief.” William Scott of Pennsylvania, his blood also up in defense of Franklin, launched a frontal assault on the constitutional position of the Deep South: “I think it unsatisfactory to be told that there was an understanding between the northern and southern members, in the national convention”; the Constitution was a written document, not a series of unwritten understandings; where did it say anything at all about slavery? Who were these South Carolinians to instruct us on what Congress could and could not do? “I believe,” concluded Scott, “if Congress should at any time be of the opinion that a state of slavery was a quality inadmissible in America, they would not be barred … of prohibiting this baneful quality.” He went on for nearly an hour. It turned out to be the high-water mark of the antislavery effort in the House.46

In retrospect, Franklin’s final gesture at leadership served to solidify his historic reputation as a man who possessed in his bones a feeling for the future. But in the crucible of the moment, another quite plausible definition of leadership was circulating in the upper reaches of the government. John Adams, for example, though an outspoken enemy of slavery who could match his revolutionary credentials with anyone, concurred from his perch as presiding officer of the Senate when that body refused to permit the Quaker petitions to be heard. Alexander Hamilton, who was a founding member of the New York Manumission Society and a staunch antislavery advocate, also regretted the whole debate in the House, since it stymied his highest priority, which was approval of his financial plan. And George Washington, the supreme Founding Father, who had taken a personal vow never to purchase another slave and let it be known that it was his fondest wish “to see some plan adopted, by which slavery in this country may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees,” also concurred that the ongoing debate in the House was an embarrassing and dangerous nuisance that must be terminated. Jefferson probably agreed with this verdict, though his correspondence is characteristically quiet on the subject. The common version of leadership that bound this distinguished constellation together was a keen appreciation of the political threat that any direct consideration of slavery represented in the stillfragile American republic. And the man who stepped forward to implement this version of leadership was James Madison.47