You’ve already seen it mentioned here and you’ll see it mentioned in nearly every gardening book ever written—compost. It’s the gardener’s best friend (well, after the dog), and everyone should have a compost pile or bin or something somewhere. There’s really no reason to have problems with dogs and compost, but some people do, so we’ll talk about it here.

Mulches also have a highly useful place in the landscape, but where dogs are concerned all mulches are not created equal. We’ll look at the pros and cons of the different materials available.

There may be some confusion about the difference between compost and mulch, and it’s not often explained. Many of the same materials may be used for both, but in different ways.

Mulch is some organic material in its original state—leaves, grass clippings, straw, etc.—laid on top of the soil. Sometimes “mulch” is also used to refer to inorganic materials such as gravel or weed-block fabric, but these are still applied on top of the soil.

Compost is made of organic materials that have been combined and left to break down into their more basic components, forming a loose soil-like substance called humus. Compost is nearly always worked into the soil and serves multiple purposes including lightening the soil, improving fertility, and of course recycling waste.

Compost

CONVENTIONAL COMPOST

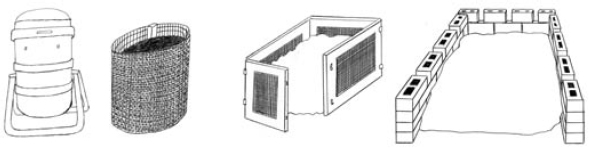

To create compost, I highly recommend a bin or enclosure of some sort. Rosie Lerner, Consumer Horticulture Specialist and Master Gardener State Coordinator, Purdue University, points out “Using a dog-proof bin to contain the compost will not only keep the dogs out, but will also make the compost easier to manage. Bins could be made out of plastic, lumber, palettes, bricks, close-mesh wire, and so on.” I love the benefits of compost, but rarely manage to water and turn as I should, so I use black plastic fully-enclosed bins that do a good job of keeping moisture and heat in and dogs and wildlife out. I have three. Two would probably have been sufficient—one full to cook on its own and one to accept kitchen scraps and the occasional weed—but three seems more pleasing as a number, allows for compost that is in an intermediate stage of “cooking,” and we have plenty of room to accommodate all.

So if you’ve never had a compost pile, how do you begin? Establish the location of your “pile” (even compost containers are often referred to as “compost piles”) and what sort of enclosure you will use and size. All of these considerations intertwine to some degree. If you’re going to use an open bin, make it big enough that you can turn the pile easily. If you invest in one of the cement-mixer-style compost tanks, which you’re supposed to crank through one full revolution every day, it makes sense to place it somewhere you’ll go every day. If you’re just going to build a fence around your pile, you may consider it somewhat unsightly and will only need to turn it every couple of weeks (though the more often you turn it, the faster the composting process), so it can be positioned in some out-of-the-way corner screened from view (as my three little black towers are). Avoid the most obvious potential problem with a dog by placing your compost enclosure outside the dog’s every-day yard area.

A secure compost bin situated in the dog yard without any problems.

The organisms that actually make compost by decomposing the materials you give them rely on two essential ingredients: carbon and nitrogen. The compost ingredients that provide carbon are called “browns” because they are generally dry, dull-colored items such as dried leaves, straw, or cornstalks. Those that provide nitrogen are “greens,” though only some are actually green, grass clippings being the most popular. But kitchen scraps and non-dog animal manure are also classed as greens. To learn more details about building an effective compost pile, consult a general gardening book, particularly an organic-oriented one, or visit www.mastercomposter.com. This excellent site has a listing of compost ingredients, whether they’re carbon or nitrogen, and how best to use them.

Compost bins of various kinds.

Some items definitely do not belong in the compost pile. Meat, bones, and fat from meat are all definite no-nos. They not only spoil, they attract vermin (and not only your dog, but neighborhood dogs, coyotes, and raccoons, as well). Milk products also spoil and can attract pests. Bread will mold, and should be left out.

What was once thought not to be a problem has recently become apparent as a very real problem—chemically treated lawn clippings. Municipalities that accept yard waste from the public found active herbicides in their compost when they investigated plant death after using the compost. So here is yet another reason to keep agricultural chemicals out of your landscape.

If finished compost has any odor at all, it should be that of freshly dug soil. Some dogs (and many cats) find this scent attractive, and it could encourage them into your garden. But compost is such an excellent soil conditioner, improving the texture as well as the fertility, that it’s more than worth this small risk.

There is one other compost option—purchasing it ready-made. Though this certainly costs more than recycling your own yard and kitchen wastes, it may be worth it to you if you find the idea of a compost pile unappealing. You can buy plastic sacks of one or two cubic feet from most nurseries for small jobs, or have a local landscaping supply bring in whole truckloads. Some municipalities have recycling/composting programs that sell the finished product as well, and even some zoos sell compost courtesy of their zebras and elephants and other grazing animals. Check around for programs near you if you would rather buy your compost than make it.

Use compost—you’ll like the results.

DOG DOO

As a popular book for children notes, Everybody Poops. And the dog is no exception. Piles of doggie excrement left on the lawn will burn the grass as surely as dog urine; it just takes longer. So poop should be picked up regularly. But then what do you do with it?

Dog owners in urban and suburban areas often use their trash collection service to dump the doo. That’s a fine choice and most municipalities permit this. Many will advise you to seal the poo in a plastic bag, to keep it away from human contact, for general health reasons (dogs can have worms and pass them into the environment, after all).

Others may choose to bury the waste. That’s what I do. Just be sure you select a location out of the way of human contact and away from the root zone of any plants you value—until it degrades, the poop will burn roots as much as it will burn lawn. Also have your dog checked regularly for worms, and treated as necessary, to avoid introducing them into the environment. Roundworm eggs can survive in the soil for a long time, and if passed from the dirt to the hands to the face (usually by children, who like to play in dirt and don’t like to wash their hands) can cause fever, asthma, or even vision problems. Tapeworms can also be transmitted, as well as such pathogens as E. coli and salmonella. There’s no need to overreact—while there is a certain level of disease hazard, it’s not the red-fag emergency warning situation some have made it out to be. Place your doggie doo dump in an out-of-the-way location and cover it regularly with soil and let nature return it to the environment.

There’s also a commercially available product called the Doggie Dooley™. This is actually a septic system in miniature, designed specifically to handle dog waste. It’s a plastic container you sink into the ground, into which you load canine poo, a “biodigester” that comes with the unit, and water. If you have one dog or two small dogs, and don’t live in a blazingly hot area of the country, this will probably work well for you. It was a bit overwhelmed by my four dogs in a toasty region of California, but admittedly, that was beyond its stated carrying capacity and it was difficult to keep the water level up as much as advised.

Another solution is to try worm composting. There is the “Dog Poo Muncher” from a company in Australia called Worms R Us. The name gives you a strong hint of how this system works. Or you could try worm composting on your own. To learn more about worm composting go to www.topline-worms.com.

Or you can do it yourself without these devices by using a system developed in Alaska, home to a substantial number of mushers and their dogs. The Fairbanks Soil and Water Conservation District was concerned about the huge amount of dog waste being trucked to the landfill or tossed in the rivers. So they conducted a study on composting dog waste. They used closed compost bins with covers. The dog waste was the “green” component and they added sawdust for the “brown,” mixed it, added enough water to make it moist, and covered it. They found the pile had to be two to three feet deep to achieve a good “cooking” temperature of over 130 degrees, and used a compost thermometer to be sure it got there. (Homeowners who want to try this but don’t have a couple of dozen dogs can add grass clippings for more volume and greens.) After about two weeks the temperature would start to decline and it was time to turn the pile. In eight weeks, the entire pile had become a loose dark dirt-like odorless substance, suitable for use in the flower garden.

The report did warn not to add new material to the pile once it started cooking, to ensure uniform decomposition, and that worm eggs could survive the process. Truthfully, there’s plenty of potential for pathogens in any soil with or without any introduction of dog waste so you should always be aware of that and wash up often. The good news for the environment, dogs, and gardens is that the Fairbanks effort was a carefully controlled experiment that showed it could be done safely if all precautions to keep the pile at the appropriate temperature were followed.

Mulches

The other nearly universally recommended garden addition is mulch. Though a wide variety of mulches are available, they accomplish the same things:

• blocking weed growth

• retaining moisture in the soil

• minimizing soil temperature fluctuation

• protecting against soil erosion

• keeping produce out of contact with the dirt

Organic mulches, including such items as garden bark and pinestraw, also gradually disintegrate, actually decomposing into the soil (though whether that process adds or deletes nutrients depends on the mulch material and the quality of your soil). They make an excellent choice for beds planted with annuals, because you can turn over spent plants, soil, mulch, and all when reworking the bed.

If an attractive, uniform surface in the garden is your main concern, inorganic mulch such as gravel will be a better choice. It won’t have to be replaced or supplemented every year or two.

Laurie Fox, Horticulture Assistant at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, advises “Don’t use mulch you wouldn’t want the dog to roll around in and then come in the house. Nothing that would attach itself to the dog and make a grooming problem. There are things that might not be friendly toward dogs, like coconut husks that have been ground up, stones or other things that have sharp points or edges. There are some dyed mulches, too, and you probably wouldn’t want to have your pet rolling around in those.” She notes that cedar is frequently used in dog bedding, so makes good dog-friendly mulch. She also warns against a material popular in the southeast, pinestraw. “Pinestraw can be very slippery. Slippery things are not a particularly good idea in a landscape.”

This rhododendron garden is well mulched with cedar bark.

The garden swing area is heavily mulched and only an occasional wild berry vine has penetrated the cover.

A mulch of special concern for dog owners is cacao (or sometimes sold as cocoa) hulls. The cacao bean, when processed, becomes chocolate, a treat that should be frmly off-limits to dogs because the theobromine contained in it is toxic to them. The hulls also contain theobromine, and the odor is pleasantly attractive and may encourage dogs to munch. Some dogs are confirmed chewers of any outdoor wood lying around. Cacao hulls can make a dog severely ill if ingested, and should never be used in areas where dogs are on their own without supervision. I wouldn’t use them at all.

Most mulch should be applied three to four inches deep to offer the best results. Or you can lay down a weed blocking fabric and then put a lighter layer of mulch over it. While the fabric does a reasonably good job of blocking most weeds, some will grow up into the holes you’ve left for your plantings and some really tenacious unwanted plants, such as wild berries, can even push their way through the fabric itself. Weed seeds blown in by the wind or carried in by animals can take root in the wood chips on top of the weed blocking fabric. Don’t think the weed-guard will solve all your weed problems. It won’t, but it will lessen your weeding chores.

Holes had to be left in the weed fabric for the seasonal peonies, but the entire garden is well mulched.

If you place organic mulches directly on the soil, be aware that as they gradually decompose, they can rob the soil of nitrogen. Should you find the lower leaves of your plants in mulched areas starting to yellow, you need to add a nitrogen-rich fertilizer (such as one rated 10-6-4) or straight ammonium sulfate.

This little garden has grown in so well you can hardly see the dog, let alone the mulch.

Check the following table for advantages and disadvantages of specific mulches for your landscape.

| Mulch Material | General Comments | Dog-Specific Comments |

| Cedar bark chips | Attractive, long-lasting, sweet-smelling choice. Readily available in the Pacific Northwest but perhaps not the rest of the country | No hazard other than the extremely unlikely chance of a splinter; smell good if rolled on and have a slight insect-repellant effect |

| Eucalyptus | Attractive, long-lasting, sweet-smelling choice. Can burn readily, so something of a fire hazard. | Because there have been over-the-counter shampoos with tea tree oil you may not want to use this where dogs have ready access to it |

| Cacao hulls | Long-lasting, attractive dark color. May compact and form a surface crust. May also mold on surface. | Contain theobromine, a substance toxic to dogs, and can cause serious problems if swallowed. |

| Coconut hulls | Long-lasting, interesting texture, pleasant color | May have sharp edges and can cut paws when walked on or simply be uncomfortable |

| Crushed corncobs | Often dyed various colors, so chemical dyes a worry. May retain excessive moisture. May attract vermin. | Rodents attracted by mulch may attract dogs to run through the garden or dig it up. |

| Pine needles | Usually not available unless you collect them yourself. Highly flammable. | Can have sap at ends and mat in dog’s coat. Can puncture feet. |

| Pinestraw | Available mainly in the southeast. Attractive and inexpensive, but very slippery | Particularly with elderly dogs losing strength in their hindquarters, substantial risk of slipping and falling |

| Straw | Readily available and inexpensive, but blows around easily and may contain weed seeds | May stick to dogs’ coats and be tracked into the house |

| Recycled shakes or shingles | Long lasting, but varying in texture and color. Good for informal gardens. | May have splinters |

| Heat-treated clay aggregates (brand names Terragreen, Turface) | Attractive choice, lighter than gravel, but expensive | Dyes could be a problem |

| Gravel, stone | Attractive and permanent, available in a spectrum of colors. Heavy to work with. | Check that individual stones are rounded, without sharp edges. |

You can see a little of the mulch and some of the stepping stones through this corner garden.