You can improve your landscaping to make it more dog-friendly in a variety of ways. But don’t forget that you can also improve the dog to make him or her more garden-friendly. The time spent in training your dog not only will show direct results in better garden behavior, but will strengthen the bond between you and help make your dog generally more responsive to your wishes.

The professionals at the American Nursery Landscape Association, when asked about tips for combining dogs and landscaping, replied “The single biggest factor is training of the dog. If that does not happen, nothing will prevent a dog from destroying any landscape. If you train a dog to run and romp and dig in certain areas and leave the gardens alone, it’s not an issue. No plant can withstand a dog that wants to dig it up. If an owner cannot successfully train her dog, she needs to put up a dog run or a separate fenced-in area to segregate the dog from the gardens. Pretty simple.”

When dealing with unwanted behavior, don’t jump immediately to the idea that you must stop it completely. Many behaviors we see as “problem” are instinctive deep-seated parts of the canine personality—digging by terriers or chewing by retrievers, for example—and suppression of them will likely result in the appearance of new unwanted behaviors, perhaps worse than the original problem. A dog digging up your annual beds may certainly raise your blood pressure, but change that to a dog who barks all day and you’ll find your neighbors’ blood pressure boiling and perhaps the law at your door.

So, think before you act. Is there a cause for some unwanted behavior, one that might be safely eliminated? If your dog is digging to escape the yard, the solution won’t be the same as for a dog digging to pursue underground critters. Some causes are even self-limiting—teething puppies may be destructive little chewing machines but never chew again once their permanent teeth grow in. This case only requires short-term management of the behavior.

If you can’t (or don’t want to) eliminate the cause, how about a compromise? Much behavior simply needs to be channeled to a more appropriate place or time to make it acceptable. Allowing the behavior to continue in an acceptable location means you don’t face the likelihood of “solving” one problem only to have it replaced with a worse one.

In this chapter, we’ll examine the canine behaviors most often presenting problems with the yard and garden, their varied causes, and a variety of plans for dealing with them. If you’ve never formally trained a dog before, don’t worry. It can be a positive experience for both of you, and we’ll tell you all you need to know to achieve success.

Behavior in Conflict with Landscape

To some extent, the problems you might face depend on what sort of landscaping you favor and what kind of dog you have. Dogs conflict in different ways with lawns than with vegetable gardens, and a Great Dane presents different challenges than a Yorkshire Terrier. Multiple dogs can present multiple problems, or can lessen problems by entertaining one another.

So, some of the concerns:

• Lawns—dead yellow spots, digging, tracks worn in

• Flower beds—digging, pooping, breakage

• Shrubs and small trees—chewing, breakage, peeing

• Groundcovers—tracks worn in, digging up, nesting in

• Vegetable gardens—digging, breakage, self-serve eating

As you can see, similar problems can occur across varying landscape styles, and understanding how to correct one may well lead to a solution for all.

Training does, however, require understanding, patience, and consistency if it is to succeed. You can’t expect to accept the behavior at some times, kindly correct it at others, and harshly punish it at still other times without ending up with a confused, unhappy, possibly neurotic dog. . . and a continuing conflict with the landscape.

Let’s look first at one of the most often-seen problems, digging in the yard. Many dogs dismay their humans with unwanted tunnels or holes, and the reasons are many.

Why Dogs Dig and What You Can Do About It

The word “terrier” comes from “terra” or “earth.” So no one should really be surprised that putting a dog together with the lovely loose soil of a well-maintained planting bed often results in holes, uprooted vegetation, and hard feelings. But there may be different reasons behind the excavations of terriers and those of, say, Siberian Huskies.

Dogs seem to consider digging just plain fun.

The smaller terriers and Dachshunds were originally bred to go down holes after vermin. So moles or voles or other underground inhabitants in your yard may trigger a hunt, with the dirt falling where it may. Some of these feisty canines don’t even need the excuse of real prey and simply dig because they are driven to it.

On the other hand, digging by a Husky generally has nothing to do with prey and everything to do with either comfort or entertainment. A true dog of the north, the Husky will often dig to create a cool nest in which to lie. And when that warms up, dig some more. Hounds also often appreciate a cool place to lie. Watch for shallow but wider excavations, always in the shade.

But Huskies and others of their sled dog lineage may also share a different reason for digging—escape. These are dogs historically bred to run over the next hill, after all, and a suburban plot may be a bit of a bore for them. This relates to another reason that might appear with any dog at any time—entertainment. Some dogs simply take up digging as a hobby, a way to pass the hours. Escape and entertainment needs will require your greatest efforts to curb digging without creating new problems.

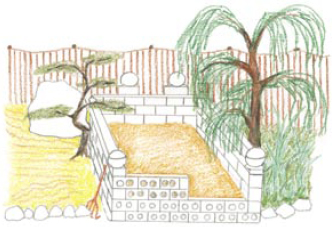

Those shade-loving loungers aren’t hard to please. All it takes to make you both happy is a little compromise. Choose a site that will stay well-shaded, especially during the heat of the day, and dedicate it to your dog’s digging desires. You can simply move any plants out of harm’s way, you can provide some encouragingly diggable dirt/sand material, or you can build an actual enclosure. It’s up to you.

A rustic, but well-shaded and dry digging pit.

Whatever you choose, select a place that won’t become waterlogged whenever you wet down the garden. While dry sand and dirt will mainly remain in the yard where it belongs, not sticking well to dog fur, wet sand and dirt can enter the home in truly astonishing quantities.

You can’t just expect your dog to adjust automatically to your new way of thinking, however. You have to convince him or her that this is the one and only place to dig. While it may take some time, it isn’t difficult.

Supervise your dog in the yard. Whenever you see him start to dig in the wrong place, don’t scold—just run to the digging area you’ve chosen, calling the dog to you excitedly. Scratch in the soft sand/dirt mix you’ve provided. Many dogs will take the hint right away and do a little tentative digging. Pour on the praise. If the dog lies down, give him a nice belly rub. Make being in the approved spot a really good experience. The more consistent you are in your supervision and encouragement to dig only where you direct, the sooner the dog will get the idea. Plan on a couple of weeks as an average training time. Once the dog gets the idea, going to the digging area on his own, still keep one eye on him. If he starts digging in any other location, interrupt him by clapping loudly. Hurry him to the digging area, point, scratch, encourage him with “good dog, dig here.” Praise when he does.

A basic digging pit design

I’ve had questions on my website (www.writedog.com) about a whole litter of puppies enthusiastically digging up the yard and housemate dogs engaging in what appears to be an all-out digging competition. If you have more than one dog and you aren’t there to see who’s digging and who’s not, you certainly can’t place any blame and you won’t know whom to train. Better to confine the dogs when you can’t supervise, either in the house or in a spacious dog run. You can train two dogs to a digging pit at the same time if you’re there to watch and if you build the pit big enough for both of them.

Your gardening style will determine what your digging pit looks like. Some may just choose a plot of ground and leave it at that, while other tastes lean more toward garden architecture. A digging pit can certainly indulge whatever degree of whimsy you may desire, so long as you also keep it functional. Plan the dimensions of the actual pit to be about as wide as your dog is long, and one-and-a-half to two times your pet’s length. These proportions give the dog room to maneuver comfortably, and keep the pit large enough so your pooch won’t kick out too much dirt. Double the dimensions if you’re building for two dogs, especially if they’re likely to want to lie in the dirt.

You can dig a foot-deep depression and build only short walls around your pit to keep the sand and dirt in, or you can start at ground level and build up. The enclosure keeps the digging materials in place the best if the walls reach the dog’s shoulders. Wood, retaining blocks, cinder blocks, and all sorts of other things will work well as digging pit walls. The choice is up to you. Cinder blocks laid in an overlapping brickwork style are sturdy and go up with a minimum of fuss. If you will be stacking them more than a row or two high, pound rebar (reinforcing rods available at lumber stores) down through the stacked holes of the blocks and into the ground to hold your walls securely in place. Leave a “door,” an opening in your walls. Fill the pit with a mix of sand and dirt to keep it loose and allow it to drain well. Proportions will vary depending on the sort of dirt being used—clay might need 50 percent sand to loosen it, while something closer to loam would be better with only 25 percent sand. Beware that too high a percentage of sand won’t provide the feel of cool dirt that the comfort diggers are seeking. Keep it looking like dirt, not beach sand.

POSSIBLE CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS FOR A DIGGING PIT

• Half-barrel planters (for small dogs)

• 2 x 4s

• Logs

• Cinder blocks

• Retaining wall block

• Rocks

• Concrete

• Stock fencing lined with canvas or tarpaulin

Of course you can always venture far beyond the basics. By all means, have fun. But keep in mind that the dog has to find the digging pit enjoyable.

A more refined digging pit design, which can actually provide a conversation piece in the garden.

DEALING WITH OTHER REASONS FOR DIGGING

So what of those other digging dynamos, who seek their little furry prey, or excitement, or escape?

For those seeking prey or excitement, periodically bury some things your dog will be happy to find in the pit. A couple of favorite toys or a variety of dry biscuits work nicely. Take your dog with you to the pit and make a big show of digging up something. Get excited and play with a toy you uncover to involve your dog.

After a minute or two of play, bury the toy again while your dog watches. Scratch the dirt over the toy, encouraging your dog to do so, too. Dogs will often dig where you’re indicating, especially when they smell the toys and biscuits. If yours does, praise extravagantly and play again when the toy is unearthed.

If you have scolded your dog for digging in the past, it may take more encouragement to get him or her started while you’re watching. Keep trying. Dig part of a biscuit up and urge the dog to pull it free. Praise any pawing, scratching, or circling in the approved area.

You may be able to entice and excite the terriers by careful choice of what you bury in the pit. Entombing a switched-on battery-powered toy will create underground sound of the sort these dogs key to, and could prove very popular. Be sure to supervise the discovery so you can rescue the toy before it’s torn to shreds. Or make a buried toy that’s designed to be torn to bits—tie a biscuit in a strip of old blue jeans and tie that in another strip. Let the dog rip it apart.

Starting puppies with self-entertainment toys will help develop a dog that can be left on his own without destroying the place.

For some really game-oriented terriers, you might also have to get rid of underground critters in your yard (moles, voles, mice, etc.) to stop any digging outside the pit. Such a program is beyond the scope of this book, but there are plenty of other resources you can consult—just be sure not to use any toxic substances that could result in damage far worse to your dog than some holes in your landscaping.

What about those individuals seeking entertainment or escape from boredom? That’s where some environmental enrichment for dogs comes in. There were some tips at the end of Chapter 4. Interesting toys also help, and it seems new products are being developed every day to occupy the long hours when many dogs must be home alone. (See the Resources for where to find toys for your dog.)

Many canine self-play toys revolve around food. No big surprise there. The pine-cone shaped Kong was one of the first, and still one of the best. It’s durable, and its hollow core can be stuffed with a wide variety of kibble, biscuits, squeeze cheese, peanut butter, and whatever else might entice your dog to work at getting every last morsel. Stuffed Kongs can also be frozen to make them even better summertime treats. Between stuffings, they can be sterilized in the dishwasher. There’s even a new device to hold a number of stuffed Kongs and dispense them one at a time to your dog throughout the day.

Many of the recently developed food-dispensing toys are designed to offer a bit of a mental challenge as well as the physical one of getting to the food. The Buster Cube can be set to dispense kibble freely as it’s nudged and tumbled by the dog, or to be more stingy and take much more effort to empty. Various brands of hollow or punctured balls fulfill the same function. Who knows what else may be in development somewhere!

Some dogs take to all of these toys, some have a favorite or two, and some just don’t seem to get it. You may want to try starting with a Kong as a relatively low-cost low-tech choice, and move up from there if you find you and your dog enjoying the challenge. You can even go completely non-tech and simply scatter handsful of kibble and biscuits around the yard or the living room. Some dogs happily hunt for their entire day’s rations this way. But you need to decide if this will work for you, or if your dog will become so excited that the food hunt actually results in more destruction.

Of course you can also enlist other humans in the effort to keep the dog entertained while you have to be off at work. Maybe a healthy retiree in your neighborhood would like nothing better than a furry companion on a daily walk—sort of having a dog without actually owning one. Or maybe a teenager would like to make some pocket money after school. Dog trainers have a saying that a tired dog is a good dog, so look at your options for offering daily exercise. It will help not only with digging, but with a whole variety of common problems.

The recommendation to get a second dog to entertain the first dog is often given without a lot of thought. first, do you want a second dog? Can you afford the added food, vet bills, etc.? Do you have time to devote to two dogs? You shouldn’t bring a dog into the home unless you truly want the dog. While two dogs may become great playmates, and some of your troubles may vanish, it’s equally likely that the dogs may not pay much attention to each other at all (so your initial problems continue) or the second dog may join in the bad behavior of the first dog (so your initial problems double!).

Dogs Who Chew and What You Can Do About It

My female retriever-type, Spirit, ate a five-foot plum tree almost to the ground. . . twice. Though this is somewhat extreme behavior, plenty of dogs do enjoy chewing, and wood is often a favored substance. Gardeners may find their trees and shrubs suffering some unwanted and unprofessional pruning at the jaws of their dogs.

I have, in the past, provided my wood-loving dogs with a pile of sticks they could call their own. Serling, in fact, become known as “the chipper/shredder” for his ability to reduce a stack of sticks to a pile of chips. I was lucky that the dogs didn’t choose to eat what they were shredding (doing so can cause intestinal problems) and that the shape of their jaws did not trap bits of wood. My current herding-sighthound mix, Nestle, chews sticks only occasionally, but several times has wedged short pieces across the top of his mouth and gone into a frenzy of pawing to try and dislodge the piece. Fortunately, I can open his mouth and remove the stick. But he obviously is not a good candidate for entertaining himself with sticks.

Still, there are plenty of other options for dogs to chew. In fact, you might find the variety overwhelming. Fortunately, nearly all pet supply stores allow your dog to come in and make his or her own selection. For unsupervised chewing, I believe that hard chews that must have pieces gnawed off (such as Bully Bones) are safer than rawhide or animal parts such as pigs’ ears, which can be chewed until softened and then swallowed whole. Consult your veterinarian or a knowledgeable shopkeeper (some are and some aren’t) for specific recommendations.

Keep in mind that your dog may want to bury treasured chew objects, so you’re back to your digging pit. To help the dog distinguish between what’s his and what’s yours, you might want to engage in some boundary training (see the section “Breakage and Self-Serve Eating” in this chapter for some tips) or return to burying treats and toys from time to time to remind him that he has a special place for digging.

This planting should prove relatively unattractive to chewing dogs, and if the grass is nibbled a bit, it will still be okay.

As with digging, if you see the dog about to chew the wrong thing, clap to interrupt the act, and redirect the dog’s attention to an acceptable chew item, whatever you’ve decided that is. You might increase the value of the object by holding onto one end while your dog chews. This will depend on your relationship with your dog—if you can’t approach the food bowl while your dog is eating, you probably shouldn’t mess with holding a chew object (and you definitely should invest in some good dog training advice and remedial education for your possessive dog).

While you’re working on training the dog, there are some handy aids available to help protect your trees and shrubs. Taste deterrents are foul-tasting substances you apply to whatever you’re trying to protect. Bitter Apple is the most popular and Bitter Orange is said to be even more bitter. They come in a spray or as a cream in a tube. They can be used indoors or out, but they are water-soluble, so after a rain or watering, you’ll have to reapply them. Not all dogs find them off-putting, so you’ll have to test to see if they work for you before relying on them.

If tree trunks are your dog’s chewing target, you can use a barrier to protect them. There are thin metal sheets for actually wrapping around trunks—though you have to be careful to allow for growth or to unwrap and rewrap regularly. Or you can install a circle of metal fencing around each tree a short distance from the trunk.

Pooping, Peeing, and W hat to Do About Them

Obviously, you can’t ask your dog not to eliminate. But you can direct elimination to a chosen area that will work for you both. That is the practical, workable solution. Do not listen to the mythology surrounding this topic, such as

• Female urine is more caustic and causes more damage;

• Changing the dog’s diet will solve the problem;

• Adding tomato juice (or salt) to the dog’s food will solve the problem;

• Putting baking soda in the drinking water will solve the problem.

None of this is true. Female dogs do tend to pee in one place, rather than marking with sprays of urine here and there, so the consequences to the lawn or groundcover can be more concentrated. But it has nothing to do with the acid or alkali nature of their urine, and changing or adding items to doggie diets—including “natural supplements” specifically advertised to result in less urine impact—will not solve your problems. The culprit, in fact, is nothing more than an overdose of nitrogen. If you were on hand to water the spot each time your dog urinated, thus diluting the nitrogen, you would find that the richest, greenest spots in the yard were where the dog had peed. But most gardeners have plenty of better things to do with their time.

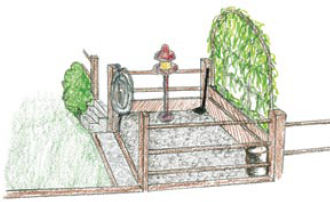

If you decide to go the “designated potty area” route here is how to proceed. Select one place that will henceforth serve as the only acceptable potty area. (With a new dog or puppy, you can do this as part of your basic housetraining program.) Consider your choice carefully. Changing your mind once you’ve begun training means starting over again. You may want to give up a small section of lawn, just letting it be used by the dog. Or you may want to actually create a potty area, with dirt or sand or gravel as the surface. Providing a vertical surface to mark is helpful with male dogs. You can use a simple post or something you find visually appealing or amusing, such as a fire hydrant. Or perhaps you have some ground around a low-hanging tree, where nothing much will grow anyway. Whatever space you choose, it is likely to develop a faint urine odor, so you do not want it to be right next to your most favored seating or entertaining area.

With male dogs, it will also help if you can avoid free access to the boundaries of your yard. Any marking done by neighborhood dogs on the outside of the perimeter will make it almost impossible for your dog to resist leaving his signature on his side of the boundary (and some dominant females feel the same way).

Once you have chosen or created the potty area, you can begin training. This requires a definite time investment on your part, but does provide a permanent solution to the problem.

If possible, choose a time when you will be home with the dog for a week or more. The more consistent you can be, the sooner you will achieve success. It will help if you know your dog’s usual schedule of elimination and pre-elimination ritual. Most dogs will circle or sniff or both immediately before relieving themselves.

At a time when your dog usually goes out for a bathroom break, take him or her outside on leash. Walk to the place you have chosen for your dog to use. Wait for your dog to do his business, and praise and give a treat after the fact. You can also give a great reward by letting the dog off leash and playing with him or her for a few minutes.

Try to use the accompanied on-leash routine every single time your dog relieves him or herself. Your efforts will suffer greatly if the dog is free to come and go through a dog door, and are almost certainly doomed to failure if the dog is kept in the yard rather than in the house.

You can design the potty area into your landscape, using fragrant vines for screening and to overcome any odors.

So, the routine is:

1. Keep your dog indoors with you until it’s time for a bathroom break.

2. Put your dog on leash and hustle outside to your potty area.

3. If your dog eliminates, praise heartily and offer a food treat.

4. If your dog doesn’t eliminate, take him or her back inside, supervise carefully or confine while you wait a half-hour, and try again.

Do your best to allow the dog to urinate and defecate only in your chosen place in the yard. Any exceptions will set back your training. If you are taking the dog out for a walk, use a different door to help the dog know the difference between going out for a potty break and going out for a fun walk.

After a week of consistently taking the dog out on leash and using your command, you should start to see the dog responding quickly to going outside (don’t forget to praise each successful trip). A second week should solidify the idea that this is the one acceptable place for elimination. If you think your dog has gotten it, try the next journey off-leash. Watch to see that the dog goes directly to the potty area.

Any slip-up means that the dog goes back on leash and the training process continues. Don’t despair. It sounds like a lot of work, especially if you haven’t done a lot of training. But plenty of people have dogs that never eliminate on the lawn, and you can, too.

By the way, be sure not to blame your own dog for what other canines in the neighborhood may be doing. After-the-fact reprimands don’t work anyway, because the dog doesn’t know what you’re talking about. If your yard is unfenced, other people’s pets or strays may be visiting and leaving their calling cards. You may see a variety of repellants for sale in stores or mail-order catalogs. Some are effective with some dogs, some are completely useless, and none seem to be totally reliable. You may also come across advice to scatter mothballs or cayenne pepper around the yard. This is obviously hazardous to your own dog (not to mention your own and neighborhood children). For keeping dogs out, there’s no substitute for a good fence. A fence will protect not just your landscaping and privacy, but your children and yourself. It can be an attractive addition to your landscaping if designed to suit your tastes. Note that the heavily promoted “electric fence,” which you bury around the perimeter of your yard, has absolutely no effect on roaming dogs because they are not wearing the special collar that delivers an electrical shock when the fence is approached.

Tracks Worn in the Yard

There is a clear path worn in the grass from our little hay shed to the rack where the sheep are fed. Two round trips a day by one human are enough to keep the grass worn down. So it should come as no surprise that a dog confined to a small area will soon wear regular pathways into the space. Dogs have favored routes, nearly always from vantage point to vantage point, or vantage point to point of nearest contact with the family, such as the back door.

You can deal with this in a few ways - incorporate the worn track into your landscaping plans or provide the dog with a roomy run for times when he or she will not be with the family.

I will tell you up front that I don’t have dog tracks worn in my yard, even the part accessible to the dogs through their dog door, because the dogs choose to spend most of their days in the house with us—the REAL benefit of working at home. They don’t even bother to go out into the yard to “defend” us from delivery persons because they have a better, closer view from the window next to the front door. How you engineer your dog’s space can have quite an impact on avoiding landscape problems.

So first consider how much time you really want the dog to spend out in the yard alone. Being isolated might create some of the problems we’ve already discussed or, even worse, constant barking. A dog is a pack animal, and the household humans are her pack. It’s just not fair to a dog to expect her to live in isolation.

Second, consider whether you want to work dog paths or a dog run into your landscaping plans. Each has its pluses and minuses.

By planning to include a path, you can position plant groupings, boulders, or even architectural elements to make the path meander in a pleasant way (though hairpin turns will encourage dogs to take the straight-line shortcut through your plantings, and should be avoided. With dogs, curves should be gentle, to encourage following them.) Paths invite people and dogs into the landscape, offering different viewpoints as you walk. You might want to “pave” your path with pea gravel or bark mulch to keep it from becoming muddy in wet weather. Both come in a variety of shades and colors to suit your particular landscape.

Avoid trouble by directing the path where the dog will want to be. Dogs are social animals and don’t take well to being away from the action. You dog will want to have a vantage point from which she can see you if you’re in the front yard and she’s in the back, or from which to keep an eye on the driveway for your return. She’ll check often at whatever door gains her entry to the house. With only some basic observation, you’ll learn your dog’s favored pathways. Trying to change them too radically is like trying to convince a river to change its course, and will only buy you problems. If you are installing new landscaping, you can even place your plants, still in their pots, where you expect to dig them in, mark where the path will go, and see how it all works out. If some adjustments are needed, they’ll still be easily made.

You can also add some training to the equation. Just as dogs can learn the difference between carpet and linoleum indoors, they can learn the differences between paths and other parts of the landscaping and adjust their behavior as necessary. Praise the dog for walking with you along the path. Encourage her back to the path if she starts to stray. Make sure the path provides access to the digging pit or any other special doggie entertainments you’ve provided.

An open space and something, or preferably someone, to play with will encourage dogs to use the space in general, without wearing in paths.

If you choose to install a dog run, see the section on that topic in Chapter 4 for some considerations.

Breakage and Self-Serve Eating

Maybe tracks in the ground aren’t a problem, but damage a bit above ground is. Dogs can engage in some pretty hearty rough and tumble, and plants within their play zone may suffer for it—broken branches, trampled flowers, even whole plants snapped off. The plants you choose and where you choose to plant them can have a lot to do with how big or small a problem this might be (see Chapters 2 and 3 for more on this). Once again, you can train the dog to show a little more respect for his surroundings.

A somewhat more rare situation, but one that does occur, is dogs who help themselves to the harvest. Contrary to popular thought, canines are not strict carnivores—they have taste buds for the sweetness of fruit, and some individuals do relish a variety of fruits and vegetables. Such connoisseurs may harvest their own berries, or dig up carrots and potatoes. Mandy Book reports that her Boxer and Golden Retriever favor tomatoes, playing with the red “balls” until they squish, then eating them.

Both of these problems can be solved by fencing or boundary training. You can make your own decisions about fencing—you might want to try and keep other critters out of your fruits and vegetables as well, or you might want to have the dog there as much as possible as a deterrent to these other critters. Here is some help with the boundary training.

The process will be easier for your dog to understand if there is an actual boundary of some kind. So vegetable gardening in raised beds will give you an additional plus, as will edging materials between lawns and fruit or vegetable beds.

With your dog on leash, walk toward an area that will be off-limits to the dog, turning to walk parallel to it when you are close enough that the dog can venture into forbidden territory. If the dog puts even a paw into the out-of-bounds area, react as if the dog were running into a street full of speeding tractor trailers. Shriek “oh no!” wave your arms, use drama (dogs appreciate drama). As soon as the dog is completely out of forbidden territory, praise and pet and tell the dog how wonderful she is to avoid such missteps. Repeat several times. The dog may start avoiding the off-limits area on her own, even if you walk right up to it. Praise her if she does.

You’ll need to repeat this process all along the boundary or boundaries. Let the dog make her own decisions—don’t try to entice her in or keep her away. Just react as described above to her stepping out of bounds, and with praise when she stays in bounds. You have to demonstrate that your reaction applies to the entire boundary, whether it’s a raised bed or edging of some kind. Dogs have to be clear about where the rules apply.

When the on-leash dog will not step into the off-limits area no matter how or where you approach, try it off-leash. Keep in mind that when changing criteria like this (off-leash versus on-leash), the training is likely to take a step backward. This is normal and expected. Just react the same as you did with the dog on-leash and repeat the process, moving along the boundary. Don’t forget to praise and reward good choices.

Picking berries isn’t an activity confined to humans.

You can make your training easier by providing an area where the dog can romp and play to her heart’s content. Have some of her favorite toys there, and spend some time playing with her as often as possible. If this area is within sight of other areas you’d rather the dog didn’t go, you may well find that the dog will choose to stay in her approved area and keep an eye on you from afar.

You can also do a bit more training if you actually want to put the dog in a down stay to have her nearby but out of trouble. “Down” is a very useful command for management, but shouldn’t be abused. It’s also a troublesome command for many people to teach, but it doesn’t have to be. As it’s easier to teach “down” from a sit, we’ll first teach sit and then down.

Because of how dogs are constructed, when their noses tilt up, their backsides tend to go down. You can use this to your advantage by holding a food treat in front of the dog’s nose and then moving it backward between the dog’s ears. As the dog follows the treat with his nose, he will fold into a sit. Praise and give him the treat. (If he jumps up instead, you’re holding the treat too high—move it just over his head.)

Remember, edging gives the dog a visual reminder of off-limits areas.

Repeat this maybe half a dozen times, then try it with the same hand motion but without a treat in your hand—using a lure is a great, easy way to train, but you have to quickly get rid of the lure so you aren’t both dependent on it. Still give the dog a treat when he sits—just don’t have it in your hand beforehand. (If he doesn’t sit on just the hand motion, take a break for a few minutes, then repeat several times with the lure before trying again without it.) In this way, your hand motion of luring the dog becomes your hand signal for requesting a sit.

Practice in different places, at different times of day, wearing different clothes, assuming different positions yourself. Every detail you change is a matter of importance to the dog, and you may well have to explain that the rules still apply in each new situation.

Add a verbal command by saying it before you give your hand signal. Dogs more naturally react to body language and hand signals than to words, but by saying the word first, it begins to predict the hand signal, and the dog, eager to earn the reward, starts to react to the word. After approximately 50 repetitions, you should be able to use the word alone, the signal alone, or the two together.

Once the dog will sit reliably, you can use a lure again to teach down. With the dog in a sit, hold a treat in front of his nose, then move it straight down to the floor. If the dog’s nose follows the treat, when it’s on the floor, move it directly away from the dog so that it’s between the dog’s front paws if the dog lies down. Many dogs will follow the treat and drop into a reclining position—give them the treat and praise. But some dogs are reluctant to lie down. They may be a bit nervous and not want to be in a vulnerable position, or they may be very conf-dent and unwilling to assume what is a submissive posture for dogs. No matter the reason, you can still use a lure, but with the addition of an obstacle that will help the dog to go down without a struggle. Depending on the size of your dog, you could use a chair or a coffee table to lure the dog under, but whatever your dog’s size, you can use your own bent leg.

Sit on the floor and bend one leg enough that the dog can crawl under it. Have the dog sit on the outside of your leg. Hold a treat under your leg toward the dog. When the dog is interested in the treat, slowly move it under your leg away from the dog. As soon as the dog goes into a down to follow the treat, let him have it and praise quietly. You may need to use very high-value treats, such as steak or garlic chicken, if your dog is really reluctant to go down.

At first, reward just for the dog being willing to assume a prone position. Then ask for a little more by holding the treat and letting the dog sniff and lick it for a few seconds before letting him have it. If you had to use an obstacle to get the dog to go down, after several practice sessions with the obstacle, stay in the same position but just drop the treat to the floor in your hand and see if the dog will go down without needing the obstacle. If not, practice some more with it. But if it works without it, gradually move away from the obstacle (or work near your leg but not under it, if you’ve been using your bent knee). As with the sit, when the dog is lying down well, leave the food out of your hand and just make the same hand motion. Still remember to reward the dog. (The two common hand signals for down are to hold your hand palm downward and move it down toward the floor—sort of an abbreviated version of how you were moving the lure if you were standing while training the down—or to hold one arm straight up over your head, then swing it forward and down by your side. The latter is used more by obedience competitors.)

Once the dog will down, you can gradually work up how long the dog must stay in the down before being rewarded. At first, stay right there and only ask for a few seconds. Gradually extend the time and eventually move a little at a time away from the dog. If you are willing to work on this, you will be able to take the dog into the garden with you, put him on a down on the path or in a mulched area to be nearby while you work without getting into any trouble. Never ask for more than you have taught the dog to give, and always make it a point to release the dog and pay attention to him at least every half hour.

Give That Dog a Job!

If you find that you and your dog enjoy doing a little training, you can go a step further and have your furry friend help around the yard. Some dogs can do more than others, but even the tiniest toy can run an errand or two. Consider how your dog might lighten your gardening chores.

CANINE COURIER

Thirsting for a frosty glass of lemonade, but don’t want to have to get up, trek to the house, knock the dirt off your shoes, wash your hands to visit the fridge? Is there someone who could bring you a glass if only they knew you were dying of thirst? Send the dog to let them know! Of course, either they have to be outdoors as well, or the dog needs access to the house through a dog door or open door. Or you’ll have to also teach the dog to ask to be let in, a separate bit of training.

Teaching “find me” is a fun way to burn up some energy and provide the dog with some mental exercise, and the path to having a canine courier. Training works best with two people. One holds the dog while the target person makes a show of leaving the room and disappearing around a corner (or, outdoors, walking away and ducking behind a tree—but better to start indoors because there are fewer distractions). The holder then excitedly asks “where’s (name)? Find (name)” and releases the dog. Most dogs will make a beeline for the missing person. Be sure to praise and reward the dog for finding you. If the dog doesn’t come straight to you, whistle and call encouragingly and still praise and reward when the dog arrives.

Practice with different people, using one consistent name for each person. Gradually make the dog do more to find the target person—go around two corners and hide behind a door or in a partially open closet, go upstairs or down in the basement. Eventually, you’ll ask the dog to find someone who didn’t start out in the room with you, so the dog has to initiate the search on his or her own.

If you have a strong bond with your dog, this will be a very positive experience for you both, and the dog will soon respond eagerly to “go find.” When you’re doing well indoors, start working outdoors. You can really start to stretch the distance the dog must go to make the find, but do it gradually and make sure the dog always succeeds.

Once the dog will run to find whomever you name, you have a willing and able courier. Write notes and roll them into the ring holding the dog’s tags. Or fasten a fanny pack around the dog’s ribcage and slip a can of soda in it to send to a thirsty gardener. (Let the dog get used to wearing the fanny pack first.) Even ask for a needed hand tool to be slipped into the fanny pack.

Of course there are other ways for dogs to carry objects, and if you have a retriever type, your dog may enjoy nothing more than bringing things to you. Name items as you named people—place the object you want the dog to retrieve a short distance away, point to it, and ask the dog to “get the (tool).” Remember to praise enthusiastically and reward when your dog does so. Move the tool farther away, little by little, until it ends up where it is usually kept. Keep in mind that the dog has to be able to get to the tool, and that you shouldn’t ask the dog to fetch anything that might injure the dog. . . a pruning saw, for example. The dog won’t know to grab the tool only by the handle.

Dogs can develop an extensive vocabulary, so name as many items as you like. Remember what you have called each—if you’ve taught the dog to recognize a “trowel,” he won’t know what you mean if you suddenly call it a “digger.” Good retrievers may run across the entire yard to fetch your gloves, but even if the dog only goes five feet, it can save you having to get up from kneeling.

You can teach non-retrievers to fetch, but it takes more intensive training. They don’t have the natural urge to pick things up and bring them to you. Start by praising and rewarding the dog for being near the target object, then for looking at it, for touching it, then for picking it up. Be aware that the “bring it to me” part is often the most difficult—a lot of these dogs would much rather play “chase me” than retrieve. So don’t make the initial target object anything you really need, and never ever chase the dog to get it. Ignore any efforts the dog makes to entice you to chase, and praise enthusiastically if he comes to you, even if he drops the object along the way. This will be a long and gradual process. If you can make coming to you with the object more rewarding than running off and doing something else, you can create a retriever.

Finally, medium and large dogs can help in a major way by hauling yard supplies, trash, equipment, or whatever you need. Again, some breeds were originally used for such work—Bernese Mountain Dogs, Schnauzers, Bouvier des Flandres, Newfoundlands, and many others pulled milk carts and delivery vans through the streets of European towns for years before the automobile. Any dog of sufficient size can still do the same. Before starting on this endeavor, have your veterinarian check your dog’s bone and muscle structure—problems with shoulders, elbows, hips, or hocks could result in an injury.

Dogs in good shape, who are used to pulling and have learned to use their bodies well, can pull many times their own weight. In fact, there are competitions to see just how much canine athletes can pull. You don’t need to make your chores a weight pulling competition. A couple of bags of landscape bark in a little red wagon may be all you need for a particular project. That’s something an Australian shepherd sized dog can easily manage.

For hauling, you have two main components—equipment and training. You need to decide on equipment first so you can train the dog to your specific choice. That aforementioned little red wagon can be made into a dogcart with a conversion kit that replaces the handle with shafts. You could use the same idea with a four-wheeled yard cart, providing a lot more carrying capacity than the wagon. Or you can buy any of a variety of actual dogcarts, either two-wheeled or four-wheeled, from plain utilitarian varieties to fancy decorated parade carts. Whatever you decide on, you’ll need a pulling harness. This should have a nicely padded chest strap and a design that doesn’t restrict movement of the shoulders. Your first step will be to get the dog used to wearing the harness, which shouldn’t be very hard.

Even small dogs can bring your garden gloves and other small items.

Let the dog sniff and check out your cart. The more familiar he is with it, the less frightening it will be. Walk around the yard, you pulling the cart, with the dog walking beside you. A moving cart makes a lot of different sounds, and your dog needs to get used to the squeaks and rattles.

The hardest part for many dogs is introducing them to the idea of being between the shafts. It’s a confining, frightening idea at first. Take it slow and easy. Pull the cart by the shaft nearer you and have the dog walk between you and the cart. When the dog seems comfortable, throw in some turns so that the shaft gently bumps the dog. Praise for calm behavior. The big moment comes when you first put the dog between the shafts. What will work best for your dog? To have the shafts propped up on some cinder blocks or logs and back the dog between them? Or to have the dog stand and either pull the shafts up alongside or drop them down from above? Take your time with this—it’s important not to frighten the dog. Use plenty of praise and treats for the dog remaining calm.

Next, actually fasten the harness to the shafts and attach the traces (be sure you understand all the equipment and how it works together before using it on your dog). Let the dog stand in one place while you praise and reward, or let him take a step or two. Unhook the harness. From this point on, you will gradually increase the distance the dog pulls the cart. Then you will start actually loading the cart. Voila, you have a yard-work assistant.

People have used their dogs to help clear woods, dragging logs away. They’ve helped install garden ponds, vegetable gardens, decks and more, hauling dirt away from or to the work zone, pulling deck piers, lumber, or flagstone. Remember that dogs need breaks, too, and always appreciate praise for a job well done, and you’ll find your canine pal helping to lighten your landscaping load.

So, there you have it. Really, it’s nothing more than some forethought and a little compromise. You CAN enjoy your dog and your garden. So get out there and do it.