A section of this book was written while I was traveling alone in Budapest – a foreign place with a foreign culture and language.

The experience became a metaphor I used to frame what happens when we view art; we are invited in to explore an artist’s work, produced in his or her unique visual language. As with traveling – to extend the metaphor – the more familiar the artistic language is, the less intimidating it is to view the piece and to give an opinion on what we think of it. The Mona Lisa is a clear representation of a woman, in a representational style now widely understood, and hence, nearly everyone around the world feels comfortable declaring it to be “good art.”

But what about the completely foreign? We are faced with two choices – ignore and avoid it, or jump right in and figure out a way to understand and be understood. If art – on a basic level – is the expression of self in the form of idiosyncratic visual language, then it goes without saying that the more foreign the language is, the harder it will be for a viewer to understand or engage with it. For this reason, scholars, academics, critics, dealers, and all immediate and peripheral figures that comprise the art world become elevated figures, as they are able to translate what pieces “mean” and how the wider public should feel about them. This, in turn, makes viewers more comfortable seeing, speaking, and understanding the language; in one hundred years, Cubism went from a bastardization of traditional form to a universally-recognized, and appreciated, art historical movement.

However, when it comes to outsider art, we are often faced with a language that is, as the term implies, outside of what the everyday person knows to be art. The more that language resembles ours – say, with Grandma Moses – the quicker it becomes acceptable for those forms to quickly enter our mainstream consciousness. The more foreign and dense the imagery gets, the less comfortable we feel looking at and consuming it. Hence, we look to translators – art world insiders – to help us become a little more comfortable seeing what, in a sense, is foreign and uncomfortable. With outsider art becoming a growing field within the realm of art world professionals, there are now specialized museum curators, auction specialists, and others to help us understand the language of these products.

But what about art therapists?

As I was thinking about the similarities between viewing art and traveling, it also helped place the role of the art therapist within this world of translating and reflecting an artist’s independent language to invite others into the viewing experience. Whether using art in a psychotherapy session or art in an open-studio setting, the art therapist’s role is to help a client identify and understand his or her own language. In psychotherapy, this may lead to interpretation and deepening on the part of the therapist, while in the studio, it may be to help an artist strengthen his or her own unique style.

This is an exceedingly important element of art therapy that gets glossed over in most of the literature and education, and is, in many ways, what makes the field unique from other peripherally related disciplines: we help people see.

Despite the fact that the field of art therapy essentially depends on visual language, oftentimes the art part is forgotten. There is little-to-no crossover between art therapy and the contemporary art world, and yet outsider art – put simply, art created outside of the context of a traditional art world – has surged in popularity. However, art therapy education focuses on the psychological, the diagnostic, and at times entirely omits the idea that there is a long history of art and a contemporary art world that is increasingly listening to voices that once went unheard and accepting of the idea that art can be a manifestation of the self, no matter the artist’s background.

Problems of Definition

The majority of the literature on outsider art makes reference to the issue of defining the field – it is inherently defined by what it is not, art made by art world insiders. And yet, what makes one an insider? Hence, the umbrella usage of outsider has come to refer to everyone from individuals with mental illness, to Southern folk artists, to individual creators working according to their own context, unrecognized by the art mainstream. Therefore, outsider art is not a traditional art historical “ism” or school of art, or even definable by style (Cardinal 1994), but instead, a field that predicates acceptance of the artist and his or her biography in order to achieve outsider status, and on the product itself, which must be worthy of the designation of art.

This parallels with issues of defining art therapy. Primarily, both outsider art and art therapy can be considered overlapping due to the populations each encompasses – clients who access art therapy range from individuals in day habilitation programs, to those visiting a private practice, to children in schools. As with outsider art, defining both “art” and “therapy” in terms of a contemporary art therapy practice are equally difficult. The use of the term “art” implies subjectivity, aesthetics, and cultural influence, for example; therefore, when we seek to reconcile the art part of art therapy, it is not necessarily just in the making – it is in the recognizing of products as art. Plus, given the broad populations that access art therapy, it cannot be said that every art therapy process and practice has treatment in mind, hence even the term therapy is used in a broader context as well.

Another layer that adds to the confusion of accurately naming and defining outsider art and art therapy is that both are subject to a host of different forms of terminology that make definition even less clear. Outsider art is also referred to as self-taught, visionary, art brut, and folk art, in addition to outdated terms that were previously used. Each label carries with it a range of different meanings and so it becomes nearly impossible to pinpoint what an “outsider” looks like. Art therapy similarly goes by different names; for example, in New York, licensed art therapists practice as Creative Arts Therapists, encompassing dance and music therapists, which arguably carries a different meaning from just the use of art therapist. In Britain, art therapists can choose to practice under that designation or as art psychotherapists. With the growing use of Expressive Arts Therapies, particularly on the doctoral level in America, we add in even another layer of what is meant by the term “art” in art therapy.

Hence, both outsider art and art therapy exist in a pseudo-limbo, in which they are defined by peripheral fields and relationships, and most often, by context-to-context usage.

With outsider art, this mainly results in inconvenience. As I will discuss, attempting to write about this art while still using recognizable and suitable terminology is basically impossible, but the imperfectness of the term “outsider” has also come to stand for all that the idea really represents – work that is not definable by an accepted “fine art” cultural tradition.

With art therapy, the problem runs deeper, rooted in the establishment of the discipline in the United States and Britain. With alliances formed in mental health disciplines, art therapy’s quest for legitimization as a professional field has led to the need for fixed terminology – and definition. We are at the point today where neither art nor therapy necessarily describes the contexts that many art therapists work within, and the art component – not the creativity or the expressive, but the art component – is something that gets glossed over, both in training and in contemporary dialogue.

Studio Programs: The Cross-Section of Outsider Art, Art Therapy, and Art Education

LAND Gallery is a studio day-habilitation program for 15 artists located in the Brooklyn neighborhood of DUMBO. The artists of LAND are provided with a communal studio space, materials, and staff support to help each pursue his or her unique artistic vision. The storefront location of LAND allows for individuals from the general public to enter the space during program hours, and artists are provided the opportunity to discuss their work with potential buyers. When a piece at LAND sells, the artist receives fifty percent of the profit, allowing for economic benefit to the individuals, many of whom rely on social services for financial and life needs.

In navigating my role within this studio, I spent many hours considering my relationship to the idea of outsider art. When I began to understand that outsider art was ripe with issues of terminology and definition (not unlike what I was experiencing in art therapy), it placed a burden upon my usage of the term. Was it proper to use the term outsider when referring to individuals in a mental health context? How had other art therapists handled this issue?

My search did not get very far. As I read more about outsider art and art therapy, I noticed that certain assumptions and discrepancies about each persisted in the literature, usually based on categorical perceptions of “traditional” art. It seems as though individuals writing from an art historical or art brut perspective tend to devalue the work created in the context of art therapy as shallow, contrived, and overly influenced by the presence of the art therapist (see MacGregor 1990; Thévoz 1995). Furthermore, there are stereotypical rubrics commonly held that have a tendency to relegate the entire field of art therapy to the use of art as a diagnostic or clinical tool within the psychotherapeutic space.

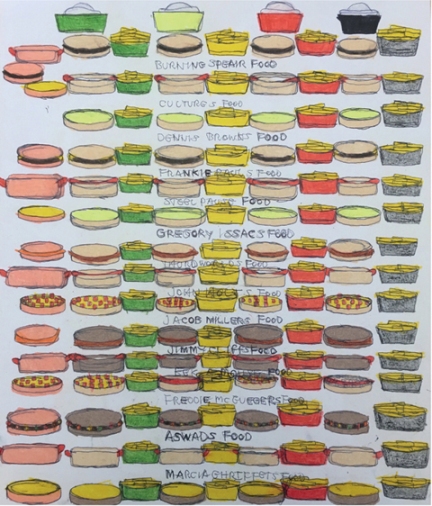

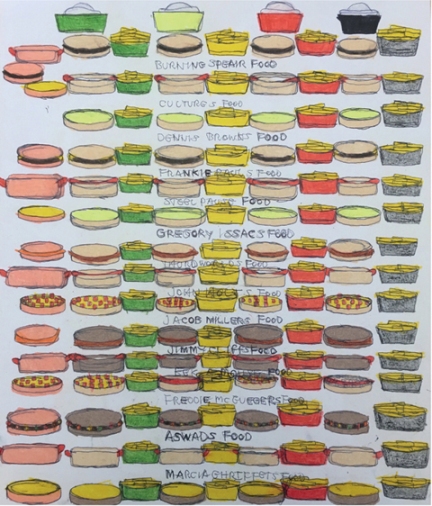

Figure I.1 Menu, Kenya Hanley, 2016. Credit: The artist and LAND Gallery. (See Color Plate 1)

Literature related to outsider art or the contemporary art world written by the art therapist is limited, and those individuals who do write about it also tend to be the individuals utilizing studio-based models. Historical literature from art therapy tends to be rooted in the writings of select “founders” of the field, and typically focuses on either the United States or England, whereas the history of studio-based artmaking as therapy, while noted, does not have as large a literature base, and hence, tends to be forgotten (Wix 2000).

My research was developed to pick up the line of thinking forwarded by others that art therapy is not exclusively a mental health field, at least historically, and that its roots traverse geographical borders (Hogan 2001; Wix 2010). In fact, I would argue that the studio-based history of the field is greater than its more notable psychodynamic counterpart, and that the main reason the latter is more focused on is due to a larger surviving written body of work. Would it not make sense that the mental health-slanted side of the field would produce more clinical written work, and would it not also make sense that the art-slanted side would leave behind more visual work, as in, art? Without an arts-based counterpart to organizations like the American Art Therapy Association and its mental health slant, this art disappears. Every so often someone mounts an exhibition of “founder’s” works at a convention or American Art Therapy Association (AATA) event, but where is the presence comparable to scholarly journals regarding the artwork of art therapy? Where are the gallery presences that consistently demonstrate the art practices of art therapy in an aesthetic or educational context?

A cover image on a quarterly publication, or opening images to a presentation do not respect the idea of art in any traditional means, and rarely, if ever, cross over with the larger contemporary fine art world. In fact, I would posit that many art therapists have no relationship with the contemporary art world at all. By doing so, we continue to reinforce hierarchies that there is a difference between the idea of Art (with a capital A) and the idea of creative expression, or what purportedly occurs under the rubric of “art” in art therapy. Not to mention, art therapists miss out on the examples of the struggles and creative processes of contemporary artists in the mainstream art world. If the art process is intrinsically one of self-discovery that challenges individuals to experience a greater whole, how can art therapists ignore that process occurring in its most prime form, the artist who dedicates his or her life to creative production? By not engaging with both art history and contemporary art, art therapists miss out on this most basic element of the field, practicing seeing and experiencing new languages – which ultimately helps shape one’s own.

The program at LAND, and other studio programs like it, in a sense serve as a perfect bridge between outsider art and art therapy. In many cases, art therapists are under-represented at these sites (Vick and Sexton-Radek 2008); this type of work requires shedding of the many skins that go along with what it means to be an art therapist, or even a therapist in general. An essential aspect of daily work in the studio program is ensuring that artists develop and maintain their own processes, and that their unique imagery and content is preserved.

Figure I.2 Barn, Linda Haskell, 2016. Credit: The artist and Pyramid Inc.

In this kind of setting, the role of the art therapist becomes one of art educator (assisting with new techniques and processes), container (keeping the public storefront space safe for all artists), and gallerist (handling sales, interfacing with collectors and the public). This type of work is not well addressed in the literature from the field of art therapy, and when I looked towards work from art history and contemporary art, or even the growing body of work on outsider art, the field of art therapy was subjected to a number of outdated stereotypes that continue to delegitimize it in a larger art context.

The idea of aesthetics plays a crucial role in the debate between art therapy as an art field and art therapy as a mental health field. In a sense, considering the role of aesthetics in art therapy demonstrates the differing viewpoints within the field. Some art therapists prefer to leave aesthetics out of the therapeutic situation entirely, considering the product to be a tool in the therapeutic process, lessening the role of “fine” art techniques, processes, and standards. Others believe aesthetics can have a powerful role in the therapeutic context, both from an art-as-therapy and art psychotherapy perspective (Henley 1992).

Quality becomes a topic of discussion in relation to art therapy, as various practitioners and artists have had varying perceptions of what “quality” in art can mean. However, there is the innate truth that there is both bad fine art and bad outsider art, including bad products of art therapy. There is a necessary component of understanding aesthetics in a well-rounded sense in order for the art therapist to learn how to appreciate the art product. By increasing awareness and understanding of outsider art, and how it has impacted historical art movements, the art therapist can better appreciate the de-aesthetics of non-traditional fine art forms, and feel more comfortable working with them.

When we remove or belittle the “art” component of art therapy, we also do no justice to the accurate development and history of art therapy. Along with the history of psychiatric care and art history, art education and art therapy also share significant overlap, particularly when it comes to the idea of art education with special populations. The earliest art therapists were art educators and in a modern sense, the art studio program is an amalgamation of art therapy and art education, in addition to a form of placement within the larger contemporary art world.

However, there is very little literature from art therapy or even art education directly addressing outsider art and all of the intricacies in definition, terminology, and relation to the art world. Art therapists, those who, instead of the psychiatrists of the past, are the ones directly engaging in artmaking with clients, perhaps do not understand how or what to do with the product in the long term. The images kept and displayed are often those that provide backup for case studies or particular theories, rarely chosen for aesthetic value or merit. This is where art education, as in learning to appreciate art and the making of it, can bridge the gap.

Figure I.3 Future HouseBoatShip, Garrol Gayden, 2010. Credit: The artist and LAND Gallery.

Spectrums of Meaning: Outsider Art and Art Therapy

Throughout the chapters in this book, I will identify a series of polarities that arise within the historical and contemporary viewpoints of both outsider art and art therapy. These are, briefly: art/not-art and art as a tool/art as an aesthetic product, which are affected by and have an effect on larger polarities of sick/healthy, and inside culture/outside culture – both of which are dependent on a hierarchical system of approval. By tracing these themes through the history and contemporary issues of both outsider art and art therapy, their relation to other fields like art and museum education, and criticisms of each, I illustrate a historical and contemporary connection between the areas of art therapy and outsider art. In doing so, I show how outsider art, art therapy, art education, and any individual’s conception of fine art, can hold varying relationships with each other, based on the continuums that form from these polarities, and thereby stimulate greater dialogue – and acceptance – among these fields. Hence, outsider art is well within the “definition” of contemporary and postmodern art – and needs to be placed within the history of art itself – and because it so often encompasses the population that art therapists engage with via artmaking, a better understanding of this placement will help reconnect art therapy with the larger art world. My goal is that art therapists will become more engaged with outsider art as another tool to help empower client-artists, and as a way to reconnect with historic roots of the field.

For ease of reading purposes, I have decided to use the term outsider art throughout this book. I will discuss issues of terminology in depth throughout, and I will clarify why, ultimately, I find the term good enough, for now. Furthermore, I will not be exploring individual artists in depth; rather, they will be used in the context of the book’s theme to illustrate examples. For those interested in more information on specific artists associated with outsider art and art brut, I recommend Cardinal (1972), Ferrier (1998), Maizels (2009), and Peiry (2001), to begin with.