SHARED HISTORIES

IN MENTAL HEALTH

Despite a shared history in a mental health context, neither outsider art nor art therapy are exclusively connected to mental health or “treatment” in a contemporary sense. However, both fields – in addition to art education – are indebted to the developments regarding artwork and mental health that occurred throughout history, and especially in the 20th century. Interestingly enough, it is psychiatrists who undoubtedly paved the way for the appreciation of outsider art by a general public – a crossover with art history that needs to be further explored – in addition to pioneering the use of creativity in healing and treatment.

It was impossible for the artwork of individuals with mental illness to be considered as worthwhile productions – or even worthy of the name of art – until the medical and social community was willing to consider the individual with mental illness to be a person. Despite the presence of mental disorders throughout history, it was not until the end of the 18th and the early 19th centuries that this became an accepted way of thinking about individuals with mental illness.

We see inklings in earlier centuries of doctors taking an interest in the art of patients, some encouraging creative expression while others sought out evidence of pathology, but by the beginning of the 20th century, there is the rise of the doctor-collector, as psychiatrists began collecting and promoting exhibitions and appreciation of these works. Whereas in the early days of mental health care, patients themselves were used as a form of amusement for the public to gawk at (Rosen 1963; Stevenson 2000), by the 20th century, their artwork was appreciated both within and outside of the asylum walls. Of course, many of these early doctor-collectors also pioneered new ideas for handling this art, in both clinical and aesthetic senses (Hogan 2001).

The same continuums that I will trace throughout this book reappear in the history of conception, treatment, and care of mental illness: the idea of art/not-art; the idea of the art product as utilitarian/the idea of the art product as aesthetic; sick/healthy, particularly in a psychological sense; and the idea of inside culture/outside culture – and who decides on such. All four of these continuums will interact with each other in various ways and contribute, in one form or another, to the development of art therapy and the appreciation of outsider art.

Early Attitudes Toward Mental Illness in Europe

In medieval Europe, mental illness was predominantly seen in two ways: as evil manifest or as spiritual rapture. The idea of “healing” for physical ailments was in the hands of religion, and since “madness” was not yet seen as a form of illness, treating it was not even a consideration. Any care was typically left to the individual’s family or religious institutions, if the individual was not entirely abandoned (Rosen 1963; Stevenson 2000). In the Middle Ages also emerged the idea of the visionary, the person with a personal connection to God. Throughout this period a multitude of manuscripts, physical fits, and hallucinations were attributed to a direct communing with God – an inspiration that many future creators of folk and outsider art would also cite.

It is most often societal changes that affect the trajectory of mental health care throughout history. Once hospital care was removed from the church’s hands during the 15th century, governments and local communities of Europe realized the increased need to take responsibility for afflicted community members (Stevenson 2000). With the separation of religion and state also came an awareness of “madness” as an idea separate from previous religious interpretations, allowing it to be explored by the burgeoning secular medical community.

When it came to care, the term is used relatively. “Care” of individuals with mental illness typically meant storing them away until death. Even this system was costly, and so, with a growing recognition that responsibility for these individuals would likely be a burden for their lifetime, we see the first attempts of a search for some sort of rehabilitation that would lessen this burden. Hence, the idea that individuals with mental illness could find some “use” to society and so the earliest forms of social support began to emerge. In England, some patients discharged from Bethlem Hospital could receive a “license” permitting them to beg on the street; the benefits ostensibly being that the released patients would be able to receive some pittance of financial support and would have stability in their “job” of begging. For the general public, donating alms to the poor was a means of repenting, so it was considered to be a mutually beneficial arrangement. Unfortunately, as with many of the social initiatives which followed, the system became corrupted, causing the practice to cease by 1675. Particularly when economic challenges started affecting Europe in the 16th century, governments worked to reduce the amount of impoverished people on the street, so most individuals ended up back in the storehouses (Rosen 1963).

This is perhaps one of the first attempts at integrating – or reintegrating – those perceived as “other,” in this case individuals with mental illness, back into society. However, the practice of begging also reinforced the existing sociocultural boundaries that delineated when a person was considered sane, and when a person was considered insane; and the cultural roles each was meant to occupy. In a sense, while the “other” was briefly invited back inside, they were made to fill a utilitarian role, as opposed to one of civilian.

As the 16th century came to an end, the winds of change pervading society led to new perspectives from the general public towards people with mental illness. There was a growing idea that madness was now a spreading phenomenon, an epidemic; therefore, it must be linked to some external force – just like the plague (Rosen 1963). However, it was still a reality that storing people away and dealing with them using isolation and harsh discipline was the easiest thing to do.

In the 17th century, the idea first emerged that mental illness may be somehow akin to physical illness, and so doctors and medical professionals began to take a more hands-on approach to the possibility of curability and treatment. The 17th century also brought with it a keen interest in studying and understanding the human condition, which led to a growing interest in differentiating the “types” of madness, as diverse as the human experience itself (Rosen 1963).

Reason was the guiding principle on how to understand and work within the world in 17th century Europe. However, with the idea that humans could be rational came the similar idea that humans could be irrational; unfortunately, exemplified at the time in the individual with mental illness. Hence, discipline and corrective measures were ostensibly used to bring the person back to “reason.” This line of thinking that behavior could forcibly be changed to fall in line with ideas of cultural normalcy, will, unfortunately, be continually traced throughout history.

While there were steps taken during the 17th century to identify different types of illness, there was still a lack of understanding in the medical community of the relation of the human body to mental illness. Therefore, “insane” was an umbrella term, applied to a host of behaviors. People were indiscriminately housed together and treated with the same methods regardless of their symptoms. Furthermore, in a time when “immoral” – and anything that could be labeled as irrational – behavior was seen against the cultural norm, this meant the same care was given whether an individual was suffering from severe mental illness or was simply a person who stood outside of approved society. With this connection of immoral behavior and mental illness, it became common to house women of “ill repute” and poorly behaved children – or even those with a different mindset from their parents – in institutions for years, or even for life (Porter 1987; Rosen 1963).

The 18th and 19th Centuries in Europe

For the most part, throughout the 18th century, the institutions that housed these individuals were essentially storage units, and their main purpose was to remove the afflicted from the public eye and society at large as cheaply as possible (Rosen 1963). With institutions like Bethlem suffering from overcrowding and understaffing, it became easier, and cheaper, to simply lock individuals away (Stevenson 2000). The general sentiment towards the mentally ill was that they were savage and animalistic in nature, a form of subhuman; proper care simply wasn’t required.

By the 1760s, both popular and medical attention was focused on increasing the availability of treatment to a larger part of the mentally ill population; the 18th and 19th centuries saw the growth of the specialized asylum, designed to care for individuals with mental illness from all classes. England, in particular, saw a surge of new hospitals becoming available for the growing population; many of these were the site of innovations in psychiatric care that we take for granted today.

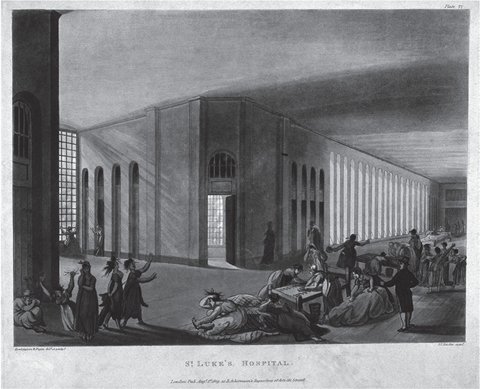

St. Luke’s Hospital was formed in 1751 as the third charitable hospital available to citizens of England. St. Luke’s innovations included prohibiting the practice of allowing curious members of the public to visit inmates as a source of intrigue and entertainment; Bethlem did not stop allowing visitors until 1770 (Hancock 1810b). At St. Luke’s, patient rooms were spacious, each with a window, and beds were designed to help catch urine in the case of bedwetting, a far cry from older institutions where patients were forced to live amidst their own filth. St. Luke’s limited the use of restraints to be used for violent outbreaks only, and common areas, dining rooms, and fireplaces provided comfort. Recreation and amusement were provided in outdoor spaces, and indoor pursuits such as knitting bridged the gap between employment and entertainment. Another major advancement at St. Luke’s was the separation of men from women, and the hiring of a staff of the respective genders to run each unit (Hancock 1810a).

Figure 1.1 St Luke’s Hospital, Cripplegate, London: the interior of the women’s ward, with many inmates and a member of staff. Coloured aquatint by J.C. Stadler after A.C. Pugin and T. Rowlandson, 1809. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

In 1766, the Manchester Royal Infirmary opened what would be the fourth public institution in England, the Manchester Lunatic Hospital; the institution was designed to provide access to poor patients. The infirmary itself, established in 1752, had been treating individuals with mental illness on an outpatient basis, so the intent was to increase the services they were able to provide within an inpatient capacity (Brockbank 1933; Brockbank 1952).

Manchester’s inpatient facility was added on to the existing infirmary, making it one of the first psychiatric institutions to be directly associated with a medical hospital. Dr. John Ferriar, hospital physician, advocated for the removal of any harsh or harmful disciplinary or restrictive measures, and treatments were to be tailored to each individual, rather than applied as a general form of care (Brockbank 1933; Brockbank 1952).

Manchester’s Hospital was moved to Cheadle in 1846, where it continued to be on the forefront of patient care. Dr. Thomas Dickson, medical superintendent, initiated programs like “work therapy” for patients, and his successor, Henry Maudsley, who took over in 1858, continued this tradition by adding more resources for patient employment and recreational activities (“Cheadle Royal Celebrates its Bicentenary” 1966).

The York Asylum was established in 1777 as yet another institution to offer care to England’s poor individuals with mental illness; York Asylum was to be a place that anyone from any class or background could enter (Digby 1983) and serves as an example of the problems that beset the massive Victorian asylum.

For years, York was considered to be the model of patient care; a complete lack of oversight made it easy for the public and government to assume that the glowing reports coming from within were accurate. However, as tales of patient deaths, harsh punishment, overcrowding, filth, and lack of food began to emerge, by 1813 the Asylum was considered to be one of the worst in England (Digby 1983). From the perspective of the administration, these practices were necessary to sustain the Asylum, as the idea of positive treatment – while idealistically pleasant – was in harsh contrast to the financial realities of running a massive hospital.

It is no surprise then, that the Asylum also highlighted the difference between care of the well-off and care of the poor. While it had been originally designed to include services for the impoverished, with mounting financial difficulties, the Asylum began to provide very different treatment to patients from different classes. The rich were well cared for, provided with entertainment, and given spacious accommodations – paying for it, of course. The poor, on the other hand, were left in overcrowded cells, kept from outdoor spaces, and were treated harshly (Digby 1983). Even in methods of care, the stratifications inside the Asylum’s walls echoed those seen in the class differences outside of the walls, a further interplay of what it meant to be inside and outside of culture.

England’s asylums provide a good history of the changes in and limitations of psychiatric care, but similar developments were also occurring throughout the continent. In 1774, the first law on insanity in Europe was passed in Florence, Italy, in which provisions for care and hospitalization of the mentally ill were outlined – with an emphasis on positive care. In 1785, Peter Leopold II established the Hospital of Bonifacio, electing Vincenzo Chiarugi to run it (Mora 1959). Chiarugi – 26 years old at the time of his appointment – is one of the overlooked figures in psychiatric history when it comes to initiating humane forms of treatment in institutions. His 1793–1794 work, On Insanity, outlined many perspectives on mental illness that were not popularly discussed at the time, such as the influence of environmental factors on human development and on the progression of mental illness (Mora 1959).

Other changes that Chiarugi made that anticipated modern mental health care included gathering a patient history at the time of intake, which would provide a more well-rounded perspective of the patient’s life and background, allowing for the development of individually tailored treatment. He separated men and women into separate wards and prohibited any use of force outside of necessary strait jackets or soft restraints for violent patients (Mora 1959). Chiarugi’s belief was that “it is a supreme moral duty and medical obligation to respect the insane individual as a person” (as cited in Mora 1959, p.431), a far cry from the century’s earlier traditions such as allowing the public to gawk at the patients locked inside.

Treating individuals with mental illness humanely was not without precedent. In the Belgian town of Gheel, which dates to medieval times, patients at the community hospital were directly engaged with the local townspeople by the 18th century. Initially, this was in the form of patients visiting the town during the day, but it also extended to local families “hosting” patients for dinners and events in a community atmosphere. Years before deinstitutionalization was even a thought, Gheel showed that positive treatment could have lasting effects when it came to long-term care and integrating individuals with mental illness with society (Yanni 2007), a blurring of lines of who was considered inside and outside of the immediate culture.

At the cusp of the 19th century, there was a push throughout Europe to implement new standards of treatment within the institution. Of these, moral treatment – or finding meaningful forms of work and activity that could engage patients – had a lasting effect on proper consideration of people with mental illness, in addition to the eventual establishment of the fields of occupational and art therapies.

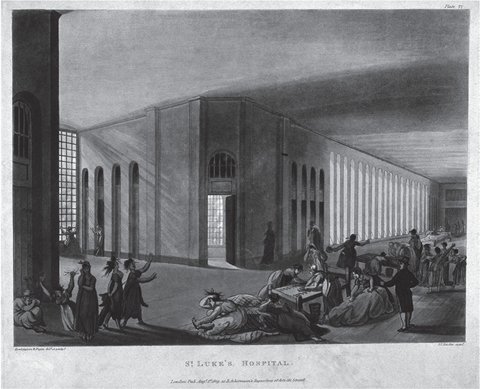

In France, Philippe Pinel – perhaps the name most often associated with advocating for moral treatment – began his revolutionary methods with positions at France’s Bicêtre from 1793 to 1795, and Salpêtrière from 1795 to 1826. Pinel’s 1806 book explored everything from the influence of patients on each other to the benefits of recreational activity and individually tailored treatments.

Figure 1.2 Pinel freeing the insane from their chains (at la Salpêtrière). Oil painting by T. Robert-Fleury, ca. 1876. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

An intriguing example of Pinel’s new methodology as illustrated in his book was a case study on a patient who descended into a state of “madness” due to a low point in his artistic career. Institutionalized under Pinel’s care, the patient was isolated for months upon his entry to the Bicêtre, but once his violent tendencies had subsided, he was given free reign of open areas. Over time, he began to ask for painting materials and started creating portraits. The hospital administration decided to support these endeavors and asked the patient to create a work for the board, allowing him to choose the subject. Pinel notes how the prospect overwhelmed the patient, who “requested that the subject might be fixed upon” (1806, p.199), pleading for what we might think of as a structural boundary in the form of limitations. When the board was unable to comply with his requests, thinking they were giving him the freedom of choice, the patient again perceived himself as a failure, destroyed all of his artwork and materials, and sunk into a state of despair that eventually ended with his death from illness.

Another major development in moral treatment was the establishment of the York Retreat in 1796 as a response to the downfall of treatment standards at the nearby York Asylum. William Tuke founded the Retreat as a Quaker institution that was in direct opposition to the treatment at the Asylum, focusing instead on the community as family and encouraging the development of interpersonal relationships. Proper care and comfort were to be of the utmost importance; the impetus for the Retreat’s founding was the death of a Quaker woman at the Asylum. Hence, the Retreat was founded with a committee who would provide careful oversight of the institution regularly (Hancock 1812). The Retreat’s pastoral setting, which Hancock described as having “no appearance of a prison, but rather resembles a large rural farm” (p.256), provided a landscape within which patients could rest and be restored. Within its walls, the appearance of the facility was also one of ease and comfort. Rather than the typically barred windows and huge gated doors, small locks were installed, and windows were left exposed. Hancock was particularly impressed with the way the Retreat was able to combine a positive atmosphere while still maintaining rigorous safety methods, and with the activities provided to keep individuals engaged. Patients were encouraged to regularly access reasonable means of employment and recreation, such as gardening or sewing.

While France and England were hubs of innovative activity regarding housing and treating individuals with mental illness, other European nations were also approaching mental illness in new ways. In Germany, Johann Christian Reil’s 1803 work laid out how humane treatment of those with mental illness was the best way of potentially curing or rehabilitating them. He looked at mental illness as a medical concern, and considered that, as with other illnesses, with appropriate treatment, they too could be cured, or at least managed (Hansen 1998).

Importantly, Reil utilized creativity; he recommended using art and music as methods of subduing patients and alleviating hallucinations, and used symbolic forms to help patients connect with their feelings. He also used a form of talk therapy with patients who showed an ability to handle these lines of inquiry (Hansen 1998).

New Territory: Mental Health Care in America in the 18th and 19th Centuries

The 18th and 19th centuries were a period of establishing nationalism and a sense of identity in the United States. A growing awareness of mental illness led to innovations and experimentation in methods of care and treatment early on in the country’s history; when the first hospital in the colonies was established in Pennsylvania in 1752, its foundation also included providing medical care for individuals with mental illness (Tomes 1982).

Benjamin Rush is the person most often associated with the introduction of moral treatment to the United States. Between 1783 and 1813, Rush worked at the newly-established Pennsylvania Hospital, where he was responsible for such treatment initiatives as providing employment and recreational activities for patients (Rush 1812). However, given the transitional nature of the time, he also still advocated for physical treatments like blood-letting and purging, while his European counterparts were moving towards methods of healing that focused on the psychological. Practices such as allowing spectators to gawk at inmates were still the norm in a growing America, despite falling out of favor in Europe. In the spirit of reason that pervaded the 18th century, the treatment paradigms at Pennsylvania were mostly developed to help reintroduce the insane – people who were believed to have lost touch with reason – back to a “rational” pattern of thought and action, and, hence, back “inside” accepted culture.

Rush was, however, also intrigued by the idea that mental illness was a disease of the mind, and he paid attention to the creative impulses he observed in his patients. In addition to observing talents in music, writing, and performance, Rush believed that patients could acquire a “talent for drawing, evolved by madness” (1812, p.154). These works were “wonderful” and visually compelling in Rush’s opinion, marking one of the first times that artwork from patients with mental illness was granted attention – and even a sense of aesthetic integrity and approval.

The Pennsylvania Hospital was founded with a governing body responsible for introducing and implementing the institution’s standards; as opposed to places like York Asylum, which were plagued by mismanagement and opacity, the board at Pennsylvania focused on transparency and patient comfort. Members included a number of important Quaker figures from the community; perhaps this explains why the environment resembled Tuke’s Retreat rather than the European asylums (Tomes 1982). Samuel Coates, Quaker merchant, was a board member and driving force behind the hospital; he set a standard of care that included reducing overcrowding and making special provisions for the housing of individuals with mental illness. Coates kept a journal recording his frequent visits to the hospital, and his notes make clear the changing perceptions of mental illness and institutionalized patients. As with Rush, Coates noticed different forms of creative expression among patients, and he encouraged them to access activities that would foster their talents (Tomes 1982).

The New York Hospital, established in 1792, expanded to a new building in 1808 to become the New York Lunatic Asylum. In an 1815 presentation to the board, committee member and Quaker Thomas Eddy introduced a new focus for American mental health professionals more akin to the moral treatment paradigms used abroad. Specifically referencing Tuke’s work at the Retreat, Eddy’s statement allows a glimpse into how the general public perspective towards individuals with mental illness was finally turning towards an embrace of humane treatment.

Eddy’s pleas for improved treatment were based on his perspective that an individual requiring institutionalization still “possesses some small remains of ratiocination and self command” and that “they are generally aware of those particulars for which the world considers them proper objects of confinement” (1815, p.6). Because of this acceptance that mental illness did not mean that the individual was unaware of his or her surroundings in any human sense, Eddy could thereby justify more humane forms of treatment. For example, he argued that confining violent prisoners in chains and using brute force made them feel fear, and fear drives the body to act in survival mode, hence patients would become more aggressive and potentially violent when approached in this way. Therefore, Eddy believed, treatment modalities should be about calming the mind as opposed to trying to bend it towards rational thought using force and punishment. He theorized that there would be a greater chance at rehabilitation, in one form or another, if, instead of teaching patients rudimentary lessons through repetition and discipline, care was focused on teaching them how to exercise self-control and self-restraint as much as possible.

Eddy’s belief boiled down to a simple truth: “the patient should be always treated as much like a rational being as the state of his mind will possibly allow” (1815, p.9). This meant tailoring treatment to the individual, but, more than that, fulfilling basic human needs – whether creative, physical, or other. Treating patients like the human beings that they are, as Eddy saw in practice at the Retreat, meant that patients were motivated to find a sense of humanity within themselves. Partially, this included maintaining accurate records upon patient intake, so considerations like lifestyle, history of illness, religion, and employment could help inform the type of treatment each patient would receive.

Clearly, an interesting thing about this transitional period is the adoption of certain standards of patient care that we take for granted today. Not only did advocates of better treatment prioritize things like taking case histories upon intake, but they also set out to make sure communication and treatment were standardized amongst staff. Eddy (1815) proposed weekly meetings in which any patient issues, contact, or treatment from the previous week would be shared with the group. Things like ensuring that there were female attendants for female patients and the same with men meant that privacy and proper security were in place to try and reduce patient danger at every step.

Throughout the 19th century, asylums continued to crop up across the United States, some with more progressive ideas towards treatment and care than others. Friends Asylum in Pennsylvania, established in 1817, was also reminiscent of its Quaker brethren overseas, the York Retreat, and founded on similar principles of comfort and care; in a Trenton, NJ center, patients were involved in regular stage performances, an early form of drama therapy meant to help soothe their minds (Yanni 2007).

Another important development in America was the establishment in 1844 of an oversight committee, the Association of Superintendents of American Asylums for the Insane, developed to provide resources for these hospitals, ensuring oversight from a separate governing body. Eventually, in 1892, this organization changed in name to the American Psychiatric Association, established four years before what would become the American Medical Association (Tomes 1982).

Artwork and Creativity in Psychiatric Care: Appreciation and Application

For our purposes, the phenomenon of doctors taking an interest in patient artmaking really emerges in the 19th century. This is when doctors start to take notice of the artwork of their patients, and take steps to preserve and even display this work, truly the early stages of both art therapy and outsider art. Along with a growing interest in artwork and artmaking in institutions, there was an increasing body of literature that sought to address creativity as a psychological process, and its use within a mental health context.

An 1806 dissertation by a medical student at the University of Pennsylvania explored the healing potential of music as a “cure or palliation of diseases” (Mathews 1806, p.9). Mathews believed that exposing a patient to harmonious music would create harmony within the body, thereby reducing any spasmodic or convulsive behavior. For patients exhibiting mania-induced behavior, Mathews proposed beginning with soft sounds and then moving on to more “lively” music, intended to “imperceptibly draw the patient’s mind from itself” (p.14). This idea that cultural products and processes could be of use to help people manage illness would regain traction in the 20th century.

In 1823, readers were given a glimpse inside the walls of Bethlem, with a massive exploration of the life of patients by Haslam, Ridge, and Conolly; it is worth noting that artistic activity did indeed occur within Bethlem’s walls during this time. From self-designated religious prophets who created magnificent, rambling signs, to poets experimenting with all forms of creative verse, the paper’s authors encountered a number of patients who had what today would be considered a rather active artistic practice (see Haslam et al.1823, pp.18, 25, 31–32, 88).

One of the first records of a doctor taking an active interest in the artwork of patients occurred in Scotland’s Crichton Royal Hospital, founded in 1838. There, superintendent Dr. W.A.F. Browne encouraged patients to take part in creative pursuits, including visual arts, performing arts, and even writing, in the form of a patient-produced magazine (Park 2003). We know of Browne’s interest because not only did he encourage his patients to follow these pursuits, he also collected their works, making him one of the first – if not the first – doctor-collectors that would go on to springboard exposure of this art to the larger public later in the century. Browne’s collection of works dating from 1843 to approximately 1867 represents almost 70 different artists, comprised of patients at Crichton and other hospitals. These works represent a broad diversity of styles and media. Soft pencil sketches of landscapes sit alongside grand plans for a new architectural invention; drafting skill is evident in some, while loose and raw emotion is present in others. Some pieces are inscribed with patient diagnoses on the back; others were given captions by the artists themselves (Park 2003).

Browne’s work is also a clear predecessor of the development of art therapy. At Crichton, he not only respected and collected the work of patients, but he also encouraged them to create and engage with art in many forms. In the years he served as superintendent, he arranged for patients to visit art exhibitions in the community (1841), set up a “studio” in the hospital’s basement (1842), and hired teaching artists to encourage and support patient creation (1843) (Park 2003, p.144).

The Mad Genius

It was a seed planted by Romanticism that encouraged the flourishing of scholarship and study of the perceived relationship between insanity and genius amongst the psychiatric community. While flawed at its core, this argument, taken up by doctors from around the world, ultimately went on to affect the ways in which art – from both within and outside of the institution – was perceived by the public for years to come.

MacGregor (1989) traces the idea of a link between madness and genius back to Ancient Greece, and shows occurrences of it throughout time. It is on the cusp of the 20th century, however, that we have a dedicated effort from the medical community to “find” and prove this link. As MacGregor points out, with this search for a connection between mental illness and genius there also came a focus from the public on paying attention to the works of the insane – after all, the next genius may be among them.

In 1864, Cesare Lombroso began his studies on the connection between insanity, the criminal mind, and genius. Lombroso’s work, The Man of Genius, is largely considered one of the first texts that considers the topic in-depth (Cardinal 1972). Unfortunately, many of the ideas in his book – such as a focus on artwork as expressions of symptoms and illness of the creator – would go on to form some of the stereotypes that arose in modern art, outsider art, and art therapy.

Lombroso collected works from his patients, not for their aesthetic value, but to use in his studies to illustrate the qualities he perceived as typical of the art of individuals with mental illness. He would always find a way to tie in diagnostic elements within the work – for example, the tendency for alcoholics to use the color yellow (2010, p.181). It is therefore necessary to think of Lombroso’s collection as a curated illustration of case studies; it is not known what works he chose or discarded in support of his thesis.

Lombroso’s main value is that he went on to influence many of the most influential minds in the field, such as Prinzhorn, inspiring them to start their own collections of patient art. While his ideas were directed towards his goal of linking madness with genius, he noticed repeating tropes, such as an inner compulsion that drives the individual to creative expression, an “originality of invention” (2010, p.184), and other qualities that reappear again and again in the writings on outsider art: a tendency towards geometric pattern, a warped sense of perspective, and an overall “strange energy” (2010, p.180). Nearly all of these “tendencies” will be repeated in future historical texts related to outsider art from both psychiatric and art fields.

On the other hand, by drawing parallels between the work of patients that he collected and “genius,” Lombroso’s line of thinking ultimately paved the way for progress or changes to tradition to be labeled as “‘mad’ and therefore ‘unhealthy’” (Cardinal 1972, p.16) – an idea that will factor prominently in the discussion of modern art. If the presence of artistic genius meant the creator could be labeled as mentally ill, anyone could assign pathology to any great artist, known or not.

In Lombroso’s perspective, the product of patient art was deemed “useless,” in that its creator did not conceive of a function for it; therefore, these products could not hold the designation of “art.” This idea can unfortunately be seen in the history of art therapy, in which many of the art objects that are saved and shown are often those that function as case material, as it is too often believed that “art” is not created in this context. Similarly, it can even be seen in the idea that outsider artists typically do not create what they consider to be works of art – which will be shown to be an incredibly reductionist view of the entire process of creation.

The line of thinking that Lombroso started was picked up by Hungarian-born Max Simon Nordau, whose 1898 book, Degeneration, explored in-depth the “degeneration” he perceived in some of the world’s most prominent artists and authors at the turn of the century. Nordau, who came from an Orthodox Jewish family, unfortunately laid the groundwork used by the Nazis for the persecution of modern art to come, and his work was dedicated to none other than Lombroso.

Nordau’s opinion is presented right from the start: “Degenerates are not always criminals, prostitutes, anarchists, and pronounced lunatics; they are often authors and artists” (1898, p.vii). Throughout the text, it is apparent to the reader that Nordau does not like modern artists, and his chief complaint with these creators is that they do not represent what they see, and instead, subvert and change form and structure. No one is immune from Nordau’s criticism: Impressionists all suffer from “trembling of the eyeball” if their paintings purport to show what they “see” (p.27). For Nordau, anything other than classical representational painting illustrates evidence of degeneration in the creator.

Nordau also attempts to set up a greater reason for analyzing works of art using psychological principles. By laying out colors, and what they “mean” according to his own view and passages from history from selected authors, he can attribute defects on the part of the artist who uses certain colors: “Thus originate the violet pictures of Manet and his school, which sprung from no actually observable aspect of nature, but from a subjective view due to the condition of the nerves” (p.29). Schools of thought or ideological collectives of artists are looked at as similar to a “band of criminals” (p.30), and the art critic and patron John Ruskin “is a Torquemada of aesthetics” (p.77). It is not just visual artists who receive Nordau’s scathing review – Wagner, Wilde, Nietzsche, Zola, and others are considered to be some of the biggest degenerates in his perspective.

Interestingly, from Nordau’s viewpoint, the artistic impulse stems from the emotions; the artmaking activity is an attempt to rid “the burden of some idea or feeling off his mind” (p.324). For Nordau, this is a negative – good art should be objective, not filled with an artist’s “degenerate” fantasy. Unfortunately, as history has shown, Nordau’s fear of the future of art and his call for the refusal of creative innovation, for people to push back against changes to tradition, and to label creators as “degenerate,” would be a legacy that would prove all too real in the coming decades. However, Nordau’s general principles did go on to inspire others to take another look at patient art.

Both Lombroso and Nordau illustrate the fluidity between what makes a creative work art – and who decides such – and paradigms of sick and healthy as related to sociocultural judgments. It is from this perspective, then, that they are also able to place productions in a reductive position of not being art, as “sick” creators cannot produce “healthy” work.

In October 1892, Chicago doctor James G. Kiernan published his paper “Art in the Insane” in the journal The Alienist and Neurologist, perhaps the first time in America that a doctor directly addressed patient work in a comprehensive way.

Kiernan starts, as do many other doctors who explored the issue, by lining up art productions throughout history, with a focus on “early types of art,” that “are characterized by the mingling of inscriptions and drawings, and the appearance in the latter of an abundance of symbols and hieroglyphs. There is much evident imitation, undue minuteness and repetition” (1892, p.246). Kiernan does, importantly, use the term “art” in his paper, and observes a range of creative activity in patients, from drawings to sculpture. Kiernan’s work is clearly indebted to Lombroso – throughout, he builds on the latter’s theories penned in The Man of Genius, and he continues forward the idea that artistic products can show pathology – whether discussing the works of patients or those of Turner and Blake. For reference, Kiernan used Lombroso’s collection in addition to works he selected from his own patients, so in a sense, he is only surveying the products that have already been curated and selected by his predecessor as “pathological.”

Kiernan also continuously compares the works of people with mental illness to the works of cultures outside of the Western perspective. He notes repetitive symbols in patient work that he sees as reminiscent of Anglo-Saxon productions, and exaggerated details similar to artwork from China. Kiernan, closely following the precedent set by Lombroso, denigrates these productions from other cultures to “primitive,” in fact referencing Lombroso’s observation of patient work as showing “evidence of reversion to primitive art” (p.247). Kiernan concedes that the artists with mental illness he considers are “not wanting in artistic powers” and that any “would readily be taken for a true artist, educated in China or old Egypt” (p. 247) – just not in the existing Western art tradition. Interestingly, it is at this time that mainstream artists moving towards a modern aesthetic would start to look to non-traditional forms – objects created outside of Western culture or those by children or individuals with mental illness – entering into the era when “primitive” became something to aspire to rather than retreat from.

Kiernan’s paper, like Lombroso’s text, shows how culturally-determined roles can lead to fluid ideals of what determines whether a work is art, and what defines a person as sane or healthy. A patient that Kiernan describes, a priest, was diagnosed with paranoia and is an illustration of how the viewer and receiver’s role of artwork can often carry with it associations and definitions that can limit intention – and how susceptible the works of patients were to this kind of analysis. The patient, as Kiernan describes, “used to sketch his figures nude and so artfully drape them by lines as to bring the genitalia into strong relief. He defended himself against criticism that the indecency was only evident to those seeking evil” (p.248). In this case, because the patient is a priest, his background carries certain connotations and expectations – celibacy – so that when he creates artwork that represents nature – the human body – Kiernan attributes this act to some sort of perversion or lewdness unbefitting his background, despite what the patient himself says about the work. Furthermore, somewhat ironically, the patient’s work is in line with artistic traditions; he is representing nature, and using the human form, the height of artistic convention, to do so. However, despite Kiernan and Lombroso’s pathologizing of work that does not represent nature, Kiernan also sees no problem pathologizing artwork when it is “in line” with a historic tradition.

And hence, what may be one of the biggest conundrums that will emerge with outsider art, the idea that these artists are held to a far higher standard of always moving boundaries that they are not allowed to understand or permeate, boundaries set by hierarchical relationships rooted in sociocultural contexts.

Not all psychiatrists and mental health professionals at the turn of the century were exploring Lombroso’s line of thinking; in fact, many others started to pay attention to artwork and the potential it held – both aesthetic and clinical. Hence, we start to see the development of drawing tests and some of the earliest exhibitions of patient work. Bowler (1997) outlines the influence of sociocultural “shifts” in thought that impacted how and why the art of individuals with mental illness started to matter:

(i) an epistemological shift in the definition of insanity and mental functioning more generally; (ii) an aesthetic shift centering on artists’ rejection of traditional modes of representation; and (iii) a social-institutional shift involving twentieth-century avant-garde artists’ appropriation of the art of the insane as a device in their attack on modern society and the institution of art. (p.23)

Hence, when psychiatrists began appreciating the art made by patients in the early 20th century, we see a similar move towards accepting the “other” occurring as part of a sociocultural zeitgeist.

Dr. Auguste Marie took over France’s Villejuif Asylum in 1900 and immediately began showing interest in his patients’ artwork. Not only did he collect their work, but he also organized a “Museum of Madness” at the asylum. Marie’s interest shows in many ways the undeniable attraction that the work of non-traditional artists had and continues to have: spontaneity, originality, freedom from outside influence, idiosyncratic expression, unrestrained use of non-traditional materials, and an innate need for expression (Thévoz 1995).

Dr. Paul Meunier wrote under the pseudonym Marcel Réja, and his 1907 work L’Art chez les Fous addresses works created within the walls of mental health institutions; Réja’s primary source of artwork was Dr. Marie’s collection. Réja’s work presents a far more well-rounded perspective of the individual with mental illness and the idea of the artist than many before him. From his view, the characteristic “genius” – the eccentric, the creative – is himself not a “normal” part of accepted society, and therefore madness can be seen as simply another step in the diversity of the human condition. He is, in a sense, willing to see humanity as a continuum of experiences, ideas, and viewpoints that occupy different roles within and outside of culture. Réja believed that (roughly translated): “The psychic conditions governing the one and the other are also not without some kinship, crazy presenting an overly amplified way, what is in the artist a discrete indication” (p.14).

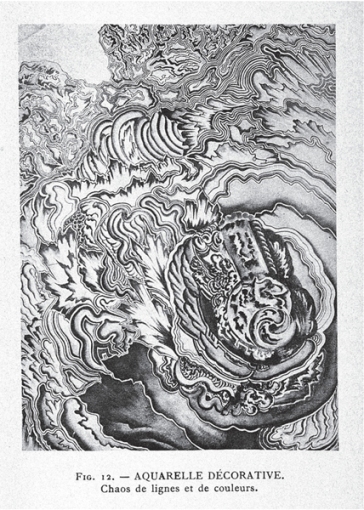

Figure 1.3 “Aquarelle décorative” from Marcel Réja, L’Art chez les Fous, 1907, fig. 13. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Réja’s overall goal does seem to be to bring attention to these patient works and devote scholarship to an area that is lacking. He discusses how patients work in all kinds of media, with content varying from spiritual revelation to copying of landscapes. He does not make an attempt to group different types of artwork according to diagnosis, as some of his contemporaries were inclined to do, instead, conceding that the variety of human functioning – seen as much in the insane as in the sane – means that no two artists work or experience their art alike.

One of Réja’s ideas that will go on to be picked up by Dubuffet and others in the 20th century is that artwork produced by institutionalized individuals shows a kind of raw expression of the human psyche (roughly translated): “For the crazy, it is a matter of inspiration, not occupation” (p.16). Similarly, like Lombroso, Marie, and others before him, Réja does notice some tropes that continue to appear in patient art, which will be further investigated in later works from both art and mental health: repetition, geometric shapes, ornamentation, text, self-grandeur, exaggerated perspective, perversion of form, and an impulse to create. However, he recognizes the work as art, and despite similarities to children’s drawings, notices that there is a sense of expressiveness and skill in the work of adult patients that shows a higher sensibility than that of children.

Finally, Réja sees the artist with mental illness as capable of expressing an originality not felt elsewhere, and more than anything, a sense of sure handedness and intention, resulting in pride for the artist regardless of what others think about his or her work: “The madman sees what he believes and not what he sees” (p.48).

A final note on Réja’s use of a pseudonym when writing about the art products of psychiatric patients. Peiry (2001) understands this as a way to ensure that he “distanced himself from institutionalized psychiatry” (p.24); by separating his professional doctor name from his art historical pseudonym, he is in a way illustrating the potential underlying discomfort in psychiatry regarding legitimizing patient creative expression as works of art.

Figure 1.4 “Aquarelle décorative: Chaos de lignes et de couleurs” from Marcel Réja, L’Art chez les Fous, 1907, fig. 12. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Another important work addressing creativity at the time was a 1905 essay penned by Joseph Rogues de Fursac, published with the intent of looking towards “writings and drawings as a valuable aid in the neuro-psychiatric clinic” (p.v); therefore, his text takes a predominantly clinical look at the work of patients and their potential value. He discusses “spontaneous writing” (p.3) which in many ways serves as a precursor to “automatic writing” – both a psychoanalytic technique and one that would be embraced by the Surrealists. While the majority of Rogues de Fursac’s work focuses on prose and poetic writing in the mentally ill, he does dedicate some room to discussing their drawings. He believes it is easier to see more nuanced diagnostic material in the written work of patients, but argues that drawings are useful for visualizing the presence of mental illness. The work of the artist with mental illness, as opposed to the sane one, “lacks the invention and, if it comes to reproduce the nature, the ability to feel the beauty of the object and therefore to express it” (p.275); hence, Rogues de Fursac saw these drawings as useful in reflecting the presence of hallucinations, the cognitive degeneration of those affected by brain disorders, and the manic tendencies of patients. In his perspective, the illness controls the artistic production: “The hand moves as guided by foreign intervention” (p.277) as opposed to being controlled by the artist’s will, once again perpetuating the idea that there is a lack of intention on the part of artists with mental illness. Rogues de Fursac (1905) includes samples of drawings of patients, with their diagnoses and commentary; for example:

Maurice N., a Catholic priest, highly cultivated mind. - Delusions of grandeur. Probably early dementia with paranoid form (insufficient information for an accurate diagnosis). - Allegories. stereotyped and inconsistent entries. Neologisms. remark the odd shape of I - Pencil Drawing. (D Chambard Collection.) (p.297)

A few years before this essay, Rogues de Fursac’s Manual of Psychiatry, first published in French in 1903, references the use of drawing tasks as a form of diagnostic testing: “Drawing: Triangle, circle, tree, automobile; copying” (Rogues de Fursac and Rosanoff 1916, p.154) in its section on “Examination for Aphasia (Organic brain damage).” This passage was taken directly from Adolf Meyer’s Outlines of Examinations, drawn up when he was at New York State’s hospital system; Meyer was a pivotal figure in the development of occupational therapy, and will be discussed later in relation to the early days of art therapy.

Another commonly cited work is Fritz Mohr’s 1906 text, written with a similar intent to address the potential applications of art in a clinical setting. Mohr, like many who would come after him, starts off with acknowledging that his interest lies in a dearth of exploration of the art of people with mental illness, but also that he, amongst other practitioners, has noticed spontaneous artmaking within his patients; he starts off by tracing the use of creative expression as a historical way of connecting with the self (1906).

Mohr lays out several drawing tasks that can be done with a patient to better understand their mental state and cognitive functioning. Interestingly, in his research and experience that led to the development of these tests, he found that spontaneously made works were far more useful than those that were directed. Mohr’s drawing tests, inspired by previous investigations from others into children’s drawings, progressed in difficulty in order to measure out the functioning levels of the individual – the first was to start out tracing a recognizable structure, to see if the patient could formulate lines and space. Later tasks would include those required to put together a story, testing conceptual development and functioning.

When Morgenthaler published his 1921 monograph on artist and patient Adolf Wölfli, he did so building off of a basis of scholarship related to productions of the mentally ill – and he references Mohr’s work as “the fundamental paper on the graphic products – nevertheless still focused on the diagnostic” (1992, p.98).

In 1916, Theodore Hyslop, Senior Physician at Bethlem, published a paper looking at the art productions of his patients. What Hyslop notices is what art brut will go on to be praised for in years to come, and the same reappearing tendencies that his predecessors recognized: an earnestness on the part of the creators, whose “artistic efforts are mostly for art’s sake” (p.34). While the works of these artists are full of distortions in perspective, linear space, and description, Hyslop acknowledges that these artists are “dead earnest” (p.34) – they are not trying to create otherworldly images and sensations, they are representing what they see and feel. However, within these transportative inner elements, there is still beauty: “seldom is the artistic instinct or technique so far deteriorated as to leave no sense of beauty in line and color” (p.34). With the growing popularity of exhibitions within asylums, Hyslop also notes how some of these artists “take glory in the attention they excite” (p.35) – showing just how much the future idea of artists outside of a traditional mainstream as unaware of the recognition they receive is flawed and erroneous, as well as the benefits towards self-esteem and empowerment that can come from exhibiting work.

In a diagnostic context, Hyslop notices that in the artwork created by people with cognitive “degeneration” skill, order, shape, and color become broken down to a basic form (p.34). These artists are attempting to represent what they actually see – a distorted view of an individual and external world. The productions of patients are also markedly different from the contemporary work that Hyslop observes in the larger art world, even the experimental post-Impressionist movements. From his perspective, “sane” artists break down forms and composition intentionally, building them back into a reintegrated whole; their new techniques are not the result of visual impairments, they are the manifestation of a synthesis of all of the artist’s knowledge into a new form of production. However, this idea that artmaking consists of a reintegrative process is one of the ideas that led to the development of art therapy as a discipline. In Hyslop’s view, a perspective that will be echoed by others after him, the art of patients, on the other hand, shows a breakdown of forms in a similar way, but the artists are not capable of the final stage of synthesis and reintegration. They are not trying to make art that breaks with tradition on purpose or because it is in fashion, they are naturally doing so.

Austrian psychiatrist Paul Schilder published another important work in 1918, where he explored the connection between experimen-tation in modern art and the artwork of his patients. By comparing the breakdown of form and figuration within the avant-garde movement to the stripped-down expressions of patients, he linked both forms of work as expressions of meaning and methods of communication – both equally valid forms of art: “If both the art of the insane and that of the nascent expressionist movement were ‘mad,’ they were both equally worthy of attention as art” (Cardinal 1972, p.16). Within his writings, Schilder managed to legitimize expressive works – whether by trained or untrained artists – as “proper” artwork; an idea that today seems obvious but that broke with artistic and psychiatric traditions of the time.

Schilder would also go on to be appointed Clinical Director of New York’s Bellevue Hospital in the 1930s, where he and his wife, psychiatrist Lauretta Bender, collaborated on integrating Gestalt theories into artmaking, laying the groundwork for the modern framework of Gestalt art therapy (Drachnik 1976).

The 1920s: Morgenthaler and Prinzhorn

Perhaps two of the most important figures in the development of both outsider art and art therapy are Walter Morgenthaler and Hans Prinzhorn. Each of these psychiatrists approached the artwork of their patients from a position of respect and appreciation – the first to do so in depth. Their works attracted the attention of modern artists who were looking away from traditional forms of representation to something new, something “other” than society and culture in a European tradition. Hence, we have the earliest stages of the artist with mental illness representing a form of “other” that exists within European culture, yet outside of it.

Morgenthaler’s 1921 monograph on his patient Adolf Wölfli was the first in-depth study of an artist living within the walls of an institution. Morgenthaler takes time to show the development of Wölfli’s artistic style with a larger focus on his artistic process and creations than on his diagnosis. While today Wölfli’s work is appreciated far outside of the context of art brut, when Morgenthaler wrote his study, he was willing to break with many of the conventions – artistic and medical – of the time. Not only did he focus on Wölfli as an artist first and a patient second, he also diverged from medical conventions of confidentiality, using Wölfli’s full name, identifying details, and personal information, as opposed to the customary use of initials or a pseudonym (Cardinal 1972; Peiry 2001). In terms of the future of art therapy and outsider art, Morgenthaler’s doing so isn’t unethical in nature; on the contrary he is placing the importance of the book on Wölfli’s art and creative process and its aesthetic value, as opposed to simply looking at or divulging the clinical details of his case. Using Wölfli’s name elevates him to the status of artist, worthy of a dedicated body of scholarly work about him, and removes him from the identity of simply “patient.”

Morgenthaler notes how Wölfli’s creative process is a form of “self-therapy,” a way to regulate his intense feelings and inner chaos through external means (Cardinal 1972, p.17). He is also one of the first psychiatrists to explicitly note the normative function of artmaking; in his perspective, if making art helps reconstitute or settle the individual’s inner self, then it inherently cannot be degenerative – it is, instead, an attempt at wholeness, or regeneration (Morgenthaler 1992, p.102). The idea of creating as normative sets the stage for the role of art in a healing context, particularly in the case of those who are institutionalized for the majority of their lives. While moral treatment and other methods of care sought to humanize the asylum patient, artmaking and creative expression took it a step further. Morgenthaler saw how being able to make – and preserve – his art allowed Wölfli to gain a greater sense of freedom in the asylum, and how he took great pride in his creations.

Morgenthaler also proposed a method of inquiry towards this art – and all art – that combines the traditional methods of both aesthetic and psychiatric-based inquiries. Rather than defining types of artist, for example, sane or insane, Morgenthaler delineates an “artist” from a “nonartist” (p.102) in a sociocultural sense: both types of person are evident in all forms of human experience, and both are multifaceted terms that encompass a range of personalities. Once again, it is the willingness for psychiatric professionals like Morgenthaler to accept the idea of a continuum of human behavior and experience, allowing for individuals to freely find and express their own sense of self, which allowed for the appreciation of creativity’s benefits.

The year after Morgenthaler’s work came one of the most legendary studies in the field, Hans Prinzhorn’s 1922 Artistry of the Mentally Ill. This seminal work would go on to influence the growth of art therapy as a discipline; art therapist Judith Rubin (1986) called Prinzhorn the “uncle” of art therapy, and his book would inspire many of the modern artists who sought out “rawer” forms of creative expression, including Dubuffet, who I will discuss in more detail in the following chapter.

Prinzhorn, who studied art history before his medical career, was appointed director of the Heidelberg Clinic’s collection of patient art in 1919 – a collection that had been started at the turn of the century when Emil Kraepelin headed the clinic (Foster 2001). Similar to Morgenthaler’s, Prinzhorn’s book in many ways attempts to avoid a strictly clinical or aesthetic approach, and he freely admits to his difficulty in defining a methodology to presenting this material, eschewing the existing frame of reference that stuck with old paradigms of “sick and healthy nor those of art and non-art that are distinguishable except dialectically” (Prinzhorn 1972, p.4). This left him to look at what the art was saying to him as a viewer of it – as opposed to what it said about the creator. His goal, in a sense, becomes to approach these works under formal circumstances not actively considered, through exploring the idea of successful creative expression in pictorial form.

Prinzhorn rejected the conclusions of predecessors like Lombroso, disagreeing with the correlation between madness and genius that they espoused. In fact, he warns against the trend of pathologizing artworks and artists from history:

When a psychiatrist considers himself justified to explain a controversial work by casting the suspicion of mental illness on an author who is unknown to him, then he acts carelessly and stupidly, no matter what his qualifications may be otherwise. (Prinzhorn 1972, p.6)

Even here, we can see a split between figures in psychiatric history; Prinzhorn disagrees with Nordau, Freud, and others who attempt to pathologize symptomology from artwork made by people they do not know.

Instead, Prinzhorn presents his text to the viewer in two ways: as a “catalog” of artwork and as “an investigation of the process of pictorial composition” (p.xvii). He remained focused on the works themselves, rather than on diagnostic or symptomatic conditions of their creators, granting them value as art objects regardless of their contexts of creation. It is worth noting that Prinzhorn referred to these productions as Bildnerei (image-making) as opposed to Kunst (art). However, he qualifies this by saying that neither term is meant to outweigh the other: “We emphasize that no aesthetic value judgments are implied when we call objects produced by bildende Kunst [creative art], Bildnerei” (p.1, n.1). His reasoning for this terminology is important in a contemporary context, as he saw the use of the word art as setting up the ability for there to be a complementary idea of “nonart” (p.1), and hence, as far too reductionist for his purposes.

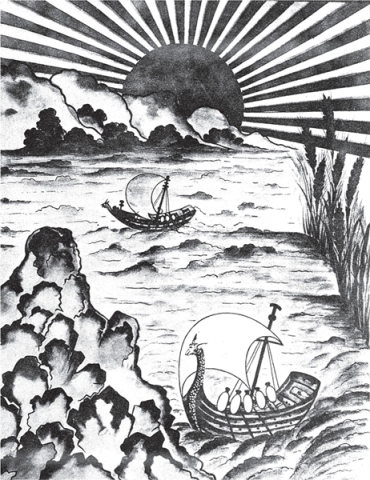

Prinzhorn’s legacy lasts in his incredible collection, the first major collection of works of artists with mental illness (Cardinal 2009; Davies 2009; Rexer 2005). Containing over 5000 works by 450 individuals, it gave the general public a glimpse into what art could mean in a modern context, and opened up the doors to an idea of universal creativity, not to mention the aesthetic appreciation of these works (Porter 1996; Rhodes 2000; Weiss 1992). Prinzhorn’s concept of configuration, and the human drive of an “inborn creative urge” (Prinzhorn 1972, p.xvii), transcends the limitations of sane and insane and exists inside and outside the walls of the institution. He observed patients creating prolific amounts of work in a spontaneous fashion, demonstrating the expanse and urgency of this basic creativity that is innate to humans: “we speak of a tendency, a compulsion, a need for the expression of the psyche” (p.13), which harks to Morgenthaler’s “normative” view of artmaking – the artist’s attempt to “make something” from psychic unrest.

Figure 1.5 “Religious Scene,” Peter Moog. From Hans Prinzhorn, Bildnerei der Geisteskranken, 1923. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Prinzhorn’s work can also help us define some of the modern terms used for describing outsider art. He chooses to stick with “Art of the Mentally Ill” because, as he notes, he is a psychiatrist approaching this work from that frame of reference, despite his efforts to avoid pathologizing them. He also describes the artists he discusses as self-taught, similar to the usage in contemporary terminology. However, Prinzhorn clarifies the term by defining them as “untrained in drawing or painting, that is they had received no instruction except during their school years” (p.3).

Prinzhorn freely admits that the definition of art itself is subjective and not fixed: “we are not able to define the perfection of a work in words other than these: it is the highest degree of vitality given the most consummate expression” (p.11). In that case, there is no way to dispute that the artwork of Prinzhorn’s patients does not contain vitality in a personalized and idiosyncratic expression. It is the dogmatic associations of what art should be and who should be an artist that caused his predecessors to reject the art created by patients, while for Prinzhorn, it is the experience of the viewer that ultimately decides whether a piece is art or not; the more successful the attempt at configuration, the more successful the viewer will perceive the work. Therefore, Prinzhorn is able to present these products, and their worth, without the need for specific judgments on their value. When he considers the artist Fritz Pohl, he says that we, the viewers, need “to look for the value of a work only with the work itself – even if it is that of a schizophrenic” (p.228). Successful configuration can just as easily be achieved within the institution’s walls as it was by Michelangelo.

Psychoanalysis and Art

The history of art and mental health in the 20th century becomes closely entwined with psychoanalytic theory, which was arguably the first time that popular global interest was paid to the mechanisms at work within a person. Surrealists, in particular, had an affinity with the psychoanalyst’s search for what was underneath a person’s skin – including the emotions, the ugliness, and the trauma – and an authentic form of expressing this unconscious; although, as will be discussed, this interest was parallel more than it was a direct influence (Gibson 1987). With the global attention that psychoanalysis brought to the idea of the unconscious, the interest in artwork of people with mental illness finally extended beyond just psychiatric attention (Bowler 1997).

Psychoanalysis would also frame a burgeoning form of art criticism that would use it as a lens for examining artwork, predominantly during the early 20th century. While the framework has largely been discredited and abandoned, its earliest days were seen in Freud’s ideas of art and artists.

It would be impossible to devote a significant section of this work to all of Freud’s ideas, but his perspectives on symbols, dreams, and his attempt at “pathologizing” Leonardo da Vinci serve our purposes best in terms of looking at the continuums discussed throughout.

In 1910, Freud published his sole biographical essay (Freud 1916), a look at Leonardo da Vinci’s work as a means of displaying what he perceived to be undertones of narcissism and homosexuality. This attempt to link a creative genius with psychosexual pathology followed in the lines of Lombroso, and Nordau, and was what doctors like Prinzhorn cautioned against; it is interesting to consider that this work was published in the same era as Prinzhorn’s and Morgenthaler’s.

Junge (2010) describes Freud’s “fascination” (p.10) with art and artists, but rather than the work itself, Freud’s main area of interest was the artist’s life. Eisler (1987) sees Freud’s book on da Vinci as reflecting an “extraordinary antipathy to the artist” (p.81), from a man who had nothing but disdain for modern concepts of art. Spector (1972) believes that Freud “expressed contrary opinions about artists, at one time admiring them and advising a hands-off policy toward their unfathomable gifts, while at another, disdaining their infantilism and calling their achievement a form of sublimated sexuality” (p.33).

Throughout Freud’s text, he attributes a deeper meaning to nearly all of da Vinci’s life and work, derived only from the literature existing on the artist’s life. For example, Freud attributes da Vinci’s slow painting process and affinity for oil paint – which is slow drying and allows for a slower process – in addition to the fact that he left some work unfinished, as “a symptom of his inhibition, a forerunner of his turning away from painting which manifested itself later” (1916, p.10). Where does he find the “proof” of this? In a note from a 1910 text entitled The Renaissance: “But it is certain that at one period of his life he had almost ceased to be an artist” (Pater, as cited in Freud 1916, p.10, n.8).

Importantly, Freud does not rely on da Vinci’s artwork to form his conclusions, but instead predominantly on written texts about the artist’s life. This distancing between the “patient” – and his or her immediate experience – and the analytic role of practitioners is one of the main problems cited about Freudian psychoanalysis; best illustrated in this case because it does not take into account any individual or unique processes. Instead, it is the role of the analyst or interpreter to “fill in the blanks.” Freud, therefore, makes assumptions like “it is doubtful whether Leonardo ever embraced a woman in love, nor is it known that he ever entertained an intimate spiritual relationship with a woman” (p.15); coupling this with an episode in which da Vinci employed a “boy of evil repute” as a model is apparently enough for Freud to conclude infantile sexual repression manifest throughout the artist’s life and work processes and a repressed homosexuality.

Freud’s concept of sublimation, or the channeling of an unacceptable idea or internal process into an alternate form of external gratification, is one of his lasting ideas that are applied to art, and one commonly used in the idea of art therapy. However, the problem with this line of thinking is, as Rexer (2005) identifies, that it gives further credence to the linkage of madness and genius, as one must have something unacceptable to expel into creative expression; in this perspective, what artmaking is not sublimatory in nature? And hence, what artist cannot be concluded to have some sort of pathology?

In terms of symbolic interpretation, most of the literature related to Freud and the arts points to the fact that he was looking for pathology or symptomology when surveying da Vinci (Foster 2001). He had an end goal in mind when starting out his search, and hence, was able to attribute elements in the artist’s life that fit his reductionist causality.

Interestingly, as will be discussed later on, Freud’s da Vinci biography may have been the starting point of a shift away from discussing an artist’s biography in an interpretive fashion, as those within the art world – and within the psychiatric discipline – saw it as a flawed and thinly-veiled attempt to reconcile the author’s own issues (Eisler 1987).

It is the theories of Carl Jung that have had more lasting power than those of Freud, particularly when it comes to the field of art therapy. In part, this may be because Jung – at an early stage in the 20th century and in the field of mental health – began to embrace and infuse Eastern ideas into his work, from yoga to mandalas (Coward 1985).

In terms of creativity, an interesting perspective of Jung’s informed by his awareness of Eastern cultures is, as his friend Herbert Read (1951a) put it: “the unconscious has creative capacities beyond the range of the conscious” (p.260). This can become manifest in dreams, and lends credence to the establishment of a universal creativity that all people are capable of – though some may need greater support to tap into their potential than others.

An area in which Freud and Jung diverge is what Read refers to as “causality.” For Freud, the importance of analysis was on discovering the root causes of current behaviors, as all issues can be traced to unresolved issues in childhood. Therefore, every element of a person – and a person’s creative and unconscious expression – could be interpreted to figure out what caused the symbols to manifest. Jung, on the other hand, did not exclusively look towards a person’s past, but also considered an element of hope that looked forward to the future. Therefore, for Jung, symbols were interpretable in more than one direction (the past). Freud reduced symptoms and symbols into what, essentially, could be considered to be a set of sexual repressions and drives from childhood, while Jung was far more willing to consider individuals as unique, despite an underlying communal awareness and unconscious that he would trace via his archetypes: “it follows that there can be no standard symbols, good for all dreams, as there are in Freudian psychology, for the purpose of the dream will vary with every individual and every situation” (Read 1951a, p.262). General symbolism can be interesting to apply, but that does not mean that an analyst can ignore the person’s unique experiences, necessary for a well-rounded understanding.

An interesting way to think about Jung in the context of the history of art therapy and outsider art is that, in many ways, he is similar to modern artists who found understanding and meaning for form and expression in what was considered to be other than Western ideology. Jung’s explorations of Eastern mythology and, perhaps most importantly for art therapists, the mandala, show that he sought universal meanings that transcended cultural boundaries. Jung’s global belief system encapsulated how the continuum of sick and healthy can be removed from the ideas of inside and outside culture, even in a mental health context.

In a paper on Picasso, Jung showed how the work of mainstream artists affected how he used art in his practice and how he saw the art products of his patients. For Jung, abstraction signaled a time in art history when emphasis was no longer on representing the external (nature), but rather the internal, the self. Therefore, in the same manner, by encouraging his patients to create, he could help “make the unconscious content accessible and so bring them closer to the patient’s understanding. The therapeutic effect of this is to prevent dangerous splitting-off of the unconscious processes from consciousness” (Jung 1966, p.136). While Freudian thought would analyze these productions to trace them to early development, Jungian thought centered on the act of production and contemplation as a means of keeping the self intact.

Ernst Kris was another analyst who, like Freud, clearly did not like modern art and its attempts at revolutionizing the cultural concept of what art meant. In 1936, he theorized that artwork could be analyzed and interpreted in the same way that Freud had shown dreams could be (Robson 1999). This development is unsurprising, given certain circles’ fascination with the analytic process, but it also has led to ongoing stereotyping of the field of art therapy as rooted in this kind of thought, and hence, as a discipline that is interpretive rather than aesthetic in nature (Junge 2010).

Kris’ 1952 Psychoanalytic Explorations in Art shared his views on art in general, the aesthetic potential of artwork created by those with mental illness, and, as with his predecessors, the common characteristics he “sees” in such work that inform his conclusions. In Kris’ perspective, an artist is not attempting to “render” or “imitate” nature, but instead, undergoes a complex psychological process – “he takes it in with his eyes until he feels himself in full possession of it” (1952, p.51) – to create something entirely new, as in, the artist’s unique perspective of the world. Taken on its surface, this statement is not entirely without merit, but Kris, as with other analysts, fell prey to conflating subjective taste with success in art. He did not see the work of artists with mental illness as “art” because in his eyes, they lacked the intentionality required in processing and translating this experience of “possession” into an identifiable, but “new,” form. Interestingly, Kris also identified stylistic elements within this work that in his view disqualified them from being considered as art: “formal rigidity and ‘emptiness,’ repetitiveness and lack of stylistic development, crude symbolism and, often, ‘horror vacui’” (Esman 2004, p.924). While certain artists and scholars were seeking out this work for these very tendencies and the potential they held for new forms in art, Kris perceived them as “non-aesthetic” symptomology.

Psychoanalysis as Critical Framework

All art criticism uses a framework through which to organize ideas and approaches. Crockett (1958) describes the most typical models, including approaching an artwork representationally (identifying objects being represented), a model focused on “plastic considerations” (the compositional and formal elements that make up the piece), an “intentional model” (taking into consideration what the artist has said), a psychological model (exploring the effects on the viewer), and a “cultural context” (taking into consideration the culture and time in which the work was created) (p.35). In the 20th century, there started a growing tendency to call for a psychoanalytic framework, which, as its name would suggest, would approach artwork with an analytical or interpretive stance based on the artist. As opposed to the intentional model, this would not rely as heavily on what the artist has said, but more about the artist’s biography, and how it is present within the work.

While it did see a surge in popularity timed with the rise of psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic criticism largely became discounted as not quite a conceptual framework that was appropriate for art criticism. The explanation for this was that a purely psychoanalytic framework did not take into account whether the art was successful, or good or bad in the eyes of the critic (Crockett 1958; Ferrari 2011). While psychoanalysis could be an interesting tool to use in forming personal associations and responses to art by an individual viewer, the way a viewer perceives a work will also be tainted by the culture and history that he or she exists within: “in art, man tends to see what he expects to see” (Ferrari 2011, p.6). Hence, parsing out elements of psychoanalytic theory like countertransference or projection would be a requirement for a critic attempting it.

An interesting way to think about the psychoanalytic framework in terms of the history of outsider art is that we can, in some ways, see a tendency for those within the psychiatric and art fields to try and attribute some sort of rationale to why and how any artist makes a particular work. The tendency to identify pathology or criminality, as with Lombroso and his peers, was essentially exploring the idea of a psychoanalytical framework even before psychoanalysis itself was established, particularly in the idea that all artists are mad or outsiders, instead of the reality, as Crockett (1958) puts it: “All people are emotionally disturbed, artists are people, and so artists are emotionally disturbed” (p.37).

Another issue seen in psychoanalysis as a critical framework is that the use of language gets tricky. A viewer may see a work by Munch and identify that it makes him or her feel “depressed,” but the term “depressed” means something very different in a therapeutic context. It can be nearly impossible to understand whether terms are being used in a clinical sense, or in an everyday language.

World War Troubles: 1930s and 1940s