SHARED HISTORIES IN ART

While the field of mental health brought nonconventional creators to light, contributions from artists and the art world were equally important in the development of outsider art and art therapy. Incidentally, many artists who championed early forms of these works learned about them because of the exposure and promotion from doctor-collectors, particularly in the early 20th century.

It is somewhat paradoxical that what we call outsider art developed in so close an alliance with mainstream art history. In many cases, the work of artists outside of Western classical traditions – whether in institutions or in foreign lands – is what spurred some of the great innovative movements of the 20th century. Yet, despite these close ties to the development of art as we know it, by definition, outsider artwork is considered to be outside of the mainstream and is largely omitted from historical narratives.

Some of the same lines of inquiry seen in the history of creativity in mental health reappear in the history of art. As there has been a perceived connection between insanity and genius since Ancient Greece (MacGregor 1989), so have artists throughout history been influenced by and interested in the topic of mental illness. Of course, there are also those notable figures who themselves spent time in institutions or underwent psychiatric treatment – and as we have seen, many of them received scrutiny from figures in the world of mental health scholarship.

In the beginning of the 20th century, the written histories of outsider art and art therapy start to diverge. With psychoanalysis inspiring the use of artwork as a source of analytic potential, the early days of art psychotherapy began, but there is also a growing recognition and awareness of the expressive potential of creativity, both as a form of communication and as a way of understanding the self in a larger public sense as well.

When it comes to outsider art, throughout art history there is an increased attention paid to the idea of the “other,” and the innovative potentials this held, but there is also a confluence of who can be defined as such. In America, the burgeoning interest was in folk art, mostly created in rural communities and subject to a wide definition, from the work of former slaves to wealthy businessmen with no artistic training. In Europe, on the other hand, artists mostly focused on finding artwork from those individuals most removed from their contemporary society – especially physically – first looking to foreign places and then to institutions to find inspiration for new forms.

The continuums that emerge when surveying the history of art are the same as those traced in the history of mental health: what is art/not-art; the perception of what constitutes an artistic product and how its use is determined; both medical and sociocultural ideas of sick and healthy; and what can be considered inside culture/outside culture. Once again, I have chosen a starting point for this admittedly brief survey of the role of the “other” in art history at the point most useful for our purposes, the 18th century.

European Artists in the 18th and 19th Centuries: The Search for Art of the Common Man

The association of insanity and creativity, traced back to the writings of Plato, reappeared in the 18th century with the flourishing of Romanticism (Beveridge 2001; Bowler 1997; Maclagan 2009; Porter 1996; Rhodes 2000). As with innovations in psychiatric history, the stimulus for new ways of thinking about art came predominantly from sociocultural changes. With the end of the classic art patronage system and a growing working class, artists and art systems had to change from their traditional ways in order to support themselves; fancy portraits and luxurious buildings were a stark contrast to the realities of the common man in 18th century Europe. While art had long been considered a trade, it was now faced with an identity crisis, largely influenced by European events such as the French Revolution. Artists were no longer meant to create work to adorn the walls of the wealthy; but what were they supposed to do instead?

Thus begins the search for a new aesthetic that will carry on into the contemporary art of today. As man became more aware of “reason,” he also became more aware of himself – and the artist became more aware of a personal style that expressed this self. Plus, with a dwindling art market in terms of wealthy patronage, artists, particularly in the late 18th century, had to find a way to attract a new clientele of buyers, which drove them in search of idiosyncratic styles, both in content and form (Gombrich 1966).

William Hogarth was one of the first artists who sought to create artwork that would resonate with the common man, something that would represent everyday life and be relatable (Gombrich 1966). Interestingly, one of his most accomplished works towards this theme, The Rake’s Progress, contains The Rake in Bedlam, a scene from a story of a man’s descent into depravity which lands him in the London asylum. The Rake in Bedlam as printed in 1735 includes a figure drawing a fantastic scene on the asylum’s walls – interesting to note in terms of the creation of artwork inside the walls of Bethlem. Even more interesting is that Hogarth chose to replace this drawing with a seal of Britannia when he reprinted the image in 1763, as a commentary on his sociopolitical surroundings (Hogarth 1833).

Figure 2.1 An insane man (Tom Rakewell) sits on the floor manically grasping at his head, his lover (Sarah Young) cries at the spectacle whilst two attendants attach chains to his legs; they are surrounded by other lunatics at Bethlem hospital, London. Engraving by W. Hogarth after himself, 1735. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Jacques-Louis David is considered the pre-eminent revolutionary painter, but his portrait of Marat Assassinated (1793) also ushered in a new era for painterly styles. Echoing yet reforming dramatic history paintings of the past, David infused this relatively simple work with great emotion, transforming the figure of Marat dying in a bath into something utterly heroic – in a new definition of the word (Gombrich 1966). Now, the ordinary man was capable of doing extraordinary things, and could be seen as a hero.

The works of both Francisco Goya and William Blake show how changes in the idea of what art was and what its purpose was allowed a new form of creative expression to develop. Both artists turned the focus of their work inwards, representing horror and mystic visions of the imagination. For Blake, in particular, the physical representation of the imagery in the work was not as important as the meaning (Gombrich 1966).

Interestingly, a September 1909 article in the British Medical Journal – and follow-up correspondence later in the year – posited that Blake’s mysticism and visionary style was the visual manifestation of the “aura” that accompanies migraines. While the original author, Munro, is responsible for the thesis, the follow-up letters wonder if, perhaps, this is an attempt by Munro to project his own analysis onto the works, because Blake had no reported history of migraines (Melland and Elliot-Blake 1909). The response letter directly challenges the idea that Blake’s visionary artwork was pathological in nature, saying that it does not give enough credit to the artist’s revolutionary productions. By the 20th century it will become clear that – as with psychiatry – there becomes a growing desire to “explain” the reasons behind changes in tradition or fantastical art production due to something in the biography of the maker, but also those defenders who seek to preserve the artist’s integrity. Blake becomes a common starting point for many of these theorists.

What made Blake’s work so important in the history of art is that it was fueled by his imagination, an idea we now take for granted (Porter 1987). At the time, accepted art was bound to the conventions of representing an idealized form of nature and man; Blake turned the art world inside out by acting instead on imagination, what was considered to be the realm of the insane in the age of reason.

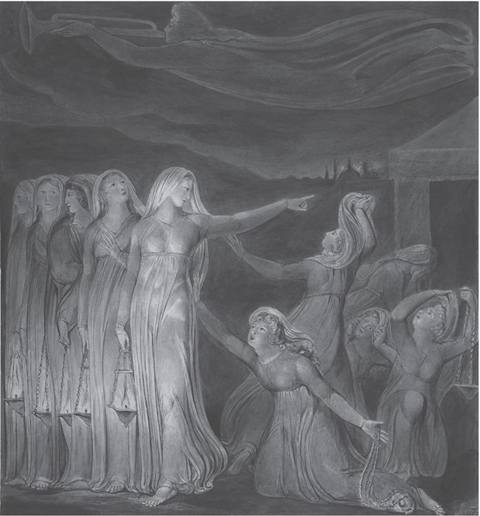

Figure 2.2 The Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins, William Blake, c. 1799–1800. Watercolor, pen, and black ink over graphite. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1914, www.metmuseum.org.

William Turner is often thought to be the artist best epitomizing representation of the “romantic” ideal of nature (Gombrich 1966), but interestingly enough, he was also the subject of a growing fascination with “understanding” the experimentation of artists through a diagnostic or pathological lens. In Turner’s case, Liebrich (1888) posited that the later style was not a conscious decision on the part of the artist, but was instead due to growing problems with his eyesight. While he looks at Turner’s art from a “scientific” rather than aesthetic perspective, he is careful to make sure that his efforts are not meant to denigrate the perceived quality or representation of Turner’s work: “Never will science be an impediment to the creations of genius” (p.18). In Liebrich’s view, if the artist is aware that he or she is suffering from some malady, the public can therefore be told that these “innovations” are the result of medical conditions, preserving and protecting cultural tradition. In fact, Liebrich’s view is that most, if not all, artists who change their “styles” do so because of a visual problem. As in the history of mental health, there is the idea that what is an accepted artistic tradition must be protected, and hence, any deviations from tradition can be explained through pathology.

In the Romantic period is when the ideal of the artist-hero flourishes. While the idea of mental illness was the height of “unreason” in the Enlightenment, by Romanticism, passion overcame reason, and the artist – and the individual with mental illness – came to represent the height of unrestrained passion. While psychiatrists were pursuing their own conclusions based on the perceived connection between mental illness and creativity, so too were artists. Insanity was starting to be seen as something not to fear, but to embrace. Romantic artists, particularly writers, saw mental illness as a freedom from the restraints of reason that had so pervaded creative production in the past (Foster 2001). Artists also began to embrace their new roles in society, in a sort of anti-heroic status as outcast (Cubbs 1994). Not surprisingly, it is also during this time that we see a tendency to look at the artist’s biography as much as their work (Eisler 1987).

By the 19th century, artists were no longer the artisans they had been throughout history; with a choice of what to create, and how to create it – and whether or not they would do so according to what the public was willing to buy – there began a general rejection of tradition (Gombrich 1966). Cultural and societal changes also led to greater access and exposure to the world, leading artists to begin to notice the potential that the other could provide. Furthermore, the more artists experimented with form, structure, and color, the more the general public and the traditionalist critics pushed them away from mainstream acceptance, setting up another dichotomy of inside and outside.

In 1832, Eugène Delacroix traveled to Morocco as part of a French diplomatic mission and the trip provided great inspiration for his future works (Mongan 1963). From the colors of the clothing and architecture, to “peuple le plus étrange” (as quoted in Mongan 1963, p.21), Delacroix saw something that was utterly different from the typical surroundings of the creative culture in France. In fact, his perspective that North Africa seemed “to be the ancient world living on into his own time” (p.23) anticipates the search for the “primitive” that would occur at the end of the century.

Figure 2.3 Saada, the Wife of Abraham Ben-Chimol, and Préciada, One of Their Daughters, Eugène Delacroix, 1832. Watercolor over graphite on wove paper. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Walter C. Baker, 1971, www.metmuseum.org.

The fact that Delacroix – who is considered to be one of the quintessential Romantics – considered the people he witnessed on his trip to be “closer to nature in a thousand ways” (Delacroix in Mongan 1963, p.29) than his contemporaries shows just how essential the work of the “other” has been to driving the biggest developments in art history forward. However, it also shows how power hierarchies can place concepts in a limiting way. For Delacroix, the native Moroccan people’s “ignorance produces their calm and happiness” (as quoted in Flam and Deutch 2003, p.415) – which is the beginning of the idea that the “other” is something pure, untouched, and naïve, as opposed to the educated, cosmopolitan insider.

The “other” was not just found in foreign lands, it was also in existence in the social surroundings of these artists, who began to take notice. Jean-François Millet, part of the Barbizon school, sought to find a subject matter in the everyday, celebrating the “heroics” of the common man as opposed to the historical greats (Gombrich 1966); his work of peasants is a far cry from his predecessors’ grand portrait paintings. Gustave Courbet continued this trend forward with what was deemed “realism,” or the representation of a common, rural lifestyle. Courbet’s intent was not formal realism but rather conceptual; in his view, the “academic” tradition of grand history paintings was not a reflection of everyday life and hence, did not accurately represent real nature (Harrison, Frascina, and Perry 1993).

With Dante Gabriel Rossetti came the Pre-Raphaelites, a group who sought to “undo” the history of painting since Raphael – who, they believed, was responsible for the traditions they were held to during their time. Rather than looking abroad, they looked back within their own cultural history, seeking out medieval works, which they saw as less attuned to style and form, and more concerned with theme and feeling (Gombrich 1966).

What united all of these artists was a search for something that represented “other” than their cultures; some finding it afar, others much closer to home.

The Breakdown of the Art Object

Danto (1997) credits Manet’s influence at the Salon of 1863 as the start of “the deconstruction of the traditional representational system of Western art” (p.33), allowing for works outside of mainstream tradition to gain further acceptance. With Manet’s influence, the transition from realistic representation to new forms would finally be complete.

Without the Impressionists we would not have contemporary art, but it is interesting to note how these artists were treated as “mad” when they started exhibiting their work. Gombrich recounts a review from 1876 that refers to the artists as “five or six lunatics” who suffer from “a delusion of the same kind as if the inmates of Bedlam picked up stones from the wayside and imagined they had found diamonds” (1966, pp.392–393).

We can see the growing problem of defining what art means in a traditional context, particularly accounting for the fluidity of time, place, and culture. With the embracing of the art of individuals with mental illness and other marginalized creators as worthy forms in themselves, modern and avant-garde artists also made it possible to continue the Lombroso-line of thinking, allowing traditionalist creators to assert “that it was not art, that all modern tendencies were equally degenerate, that direct and simple feeling was inappropriate to the accumulated culture and refinement of centuries of tradition” (Robbins 1994, p.46).

The Idea(l) of the Primitive

There was also a growing societal acceptance of appreciating other cultures in a more public way, as evidenced by the rise of the ethnographic museum. Meant for archaeological, anthropological, and ethnographic interest primarily, the display of objects from foreign cultures in a context that the public familiarly knew as one of the realms of art began to elevate and open the discussion of aesthetic appreciation to new forms (Goldwater 1967).

Perhaps it was the Romantic affinity for the “artist-as-outsider” role that spurred the earliest modern artists to start their excavation process into the art products from outside of their immediate context. As Max Weber wrote around 1913:

Definition of modernism: An eclecticism peculiar to modern civilization produced this modern-art child which happened to be born in the city of Paris. Its genealogy is Italian, Spanish, Oriental, primitive…[Its] simplification of form is derived from African, Mexican, and other primitive sculpture. (as quoted in Flam and Deutch 2003, p.419)

This is, in many ways, the break that happened in art history that allowed for the contemporary context of a democratization of art and a growing awareness in the art world of the need for inclusion. Ironically, it was caused by objects from outside of a European tradition, and from fields other than art, and yet, most of these creators are left anonymous or omitted from accepted histories of art.

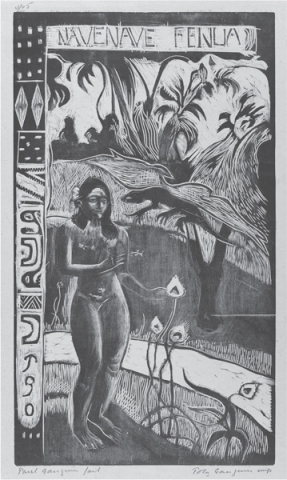

Gauguin is typically the first of the modern artists to be associated with seeking out influence in the “primitive” given his time spent in the South Pacific. However, as William Rubin (1984) points out, Gauguin’s interest was not as much about the artwork or creative objects of the people he lived amongst, but instead, in the primitive lifestyle that he experienced. Like Delacroix, Gauguin perceived of this culture as something pure and innocent, untouched by the cultural oppression of Europe. Gauguin’s work shows hints of the symbolism and objects important to the lives of the Polynesian people, but it is more in line with traditional forms of representation than with tribal forms of objects; it is perhaps his woodcuts that more successfully break from formal traditions, anticipating the German Expressionist embracing of the medium.

Griselda Pollock (1992) makes the case that Gauguin used both South Pacific culture and South Pacific women as a way to gain authenticity within modern circles as innovative; for her, Gauguin is a quintessential representation of the white, European, male artist who both controls what is considered to be mainstream, and subverts other bodies – literally – to gain authenticity as producer of innovation. This trend will unfortunately continue, encompassing issues of race, gender, and sociocultural standards.

Henri Matisse and his fellow Fauves built off of the incorporation of colors that Gauguin had set, and used tribal sculpture as inspiration for new ways of building up their compositions (Masheck 1982). However, these earliest embracers of primitive art represented more of a “synthesis of late nineteenth-century ideas” (Rubin 1984, p.7) and primitive form than a true break with it. In 1906, Matisse wrote about his first experience with art from Africa: “I was astonished to see how they were conceived from the point of view of sculptural language; how it was close to the Egyptians” (Matisse 2003, p.31). For Matisse, African sculptures held the potential of a return to a visual language in which material informs form more than content, but it also shows how even the most in-tune artists still perceived of this work as something almost trapped in the past, a relic of pure, human expression.

Figure 2.4 Delightful Land, Paul Gauguin, 1893–1894. Woodcut on china paper. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1921, www.metmuseum.org.

The Early 20th Century: Outside Is “In”

From the late 19th to early 20th centuries, the art world began paying more attention to art created outside of traditional convention as the psychiatric community did the same. Picasso, Klee, Kandinsky, and many of the other biggest names in modern art were directly interacting with non-traditional art forms as a source of inspiration.

A major sociocultural stimulant for this was World War I. For the first time, men and women from around the world were impacted by a new kind of warfare, and the passions of Romanticism could no longer reflect the experience, or aspiration, of the everyday man. In the early parts of the 20th century, it is artists like van Gogh who start to take center stage, the brooding, isolative, distressed, and decidedly non-heroic artist, whose conditions most reflected the new normal for the larger surrounding population (Eisler 1987). With the acceptance of van Gogh, whose life story – and mental illness – became a mythos intrinsically tied to his work (Bowler 1997), came the context in which artists with mental illness start to receive mainstream attention.

There are also more integrated artistic communities that develop during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. An important role of these groups is that they attempt to take the conventions of naming, describing, and interpreting style, concept, and content out of the hands of art world professionals, instead developing their own manifestos, mission statements, and goals. In addition, these groups allowed for the proliferation of ideas to develop along similar threads. Hence, when Hungarian-born gallerist Joseph Brummer opened a shop in Paris in the early 1900s, hanging African sculptures along with the paintings of Henri Rousseau, he exposed a number of artists to this work, while promoting it to the public (Paudrat 1984). However, he also set up a sort of alliance between non-traditional contexts of creation of all types that would also be propagated, leading to the current and historic problems of grouping different creators under the umbrella of outsider.

It was the Cubists who broke down the traditional idea of form and reinvigorated it with what was considered a more “primitive” feel – both alluding to earlier forms of art and to exotic tribal cultures. For example, just in Picasso’s 1907 Demoiselles d’Avignon, Rubin (1984) is able to point out traces of “African and Oceanic sculpture,” Iberian art, El Greco’s Mannerism, and even influence of the early modernists Cézanne and Gauguin (pp.9–10). But it is not only the formal elements influenced by this work; there is also a material influence. While artists like Courbet and Gauguin had felt the allure of the “other,” they still used mainly traditional modes of representation – oil on canvas with compositional clarity – whereas it is the Cubists who start to explore entirely new forms that break from tradition, like collage (Harrison et al. 1993).

It is Dada that is perhaps the movement which best represents the proliferation of new ideas of the art product in the 20th century; in fact, this was the stated goal of Dada: a “persistent desire to destroy art, the deliberate intent to wipe out existing notions of beauty” (Hugnet and Scolari 1936, p.9). There was a focus on spontaneity, social activism, and most of all, experimentation. For our purposes, Dadaists and Surrealists offer the greatest crossover with outsider art and art therapy because these artists were attempting to do what was happening – naturally – in the work of people removed from the traditional arts context, whether due to geographic or institutional borders. Artists like Kurt Schwitters – who it is assumed was familiar with the artists of Prinzhorn’s collection – worked in the same materials as the latter: found objects, detritus, and whatever was readily at hand, because he chose to, not out of necessity (Hugnet and Scolari 1936).

In a 1919 Dada exhibition, Max Ernst, associated with both Dada and Surrealism, displayed his and his peers’ work alongside “drawings of children, African sculptors, found objects, and works by the insane” (Peiry 2001, p.31) not in attempt to show their differences, but rather, to encompass a full representation of what creativity means to humanity. These works were pieces of art on their own, created by artists with as equal a claim to the title as Ernst and his compatriots.

In a 1920s Berlin show, we also see how the influence of “insanity” helped these artists overcome the limitations of tradition in formal and conceptual ways. For the event, Johannes Baader contributed a piece entitled The Baggage of Superdada upon his first flight from the madhouse, September 1899, Dada relic. Historical. A multifaceted piece echoing contemporary art today, Baader’s work “draws attention to a singular aspect of Dada – unbridled insanity” (Hugnet and Scolari 1936, p.10). Superdada, a self-imposed nickname for the artist, and the affiliated works from the series, are a kind of predecessor to the acceptance of the works of Henry Darger and other outsider artists, in that Baader used the context of his own life to foster a mystique; the difference being that it came from his own intent (Hugnet 1989).

Many of the inaugural Surrealists came from the Dada movement. However, Dada was about community, about the joint breaking down of the individual, while Surrealism, on the other hand, was more focused on the expression of the individual – the inner self projected outward. By 1924, André Breton’s experience with Dada helped him elucidate the text that would start the Surrealist movement, Premier Manifeste du Surréalisme.

Surrealism, like other modern art movements, was guided by a search for something new and different to drive visual productions. Previous centuries had been guided by the principle of “intellect,” as Read (1936) put it: “in the name of law and order and all the established hierarchies, we have been taught to respect the intellect and to submit to its control” (p.12). Therefore, Surrealism was, in a sense, a “superrealism” that sought not to represent reality in terms of subject matter, but instead to represent a heightened reality that focused on the “psychological processes involved in the creation of a work of art” (p.12) as well as those found in the viewing response. As such, Surrealists looked to the art of children, people with mental illness, folk art, and foreign “primitives” as a means of connecting to the process of artmaking removed from the constraints of Eurocentric traditional representation. Even André Masson – who broke with the group over what he perceived to be their complete handing over of creativity to unconscious process – also sought a “primitive” return to nature; in Masson’s case, he found a “savagery of nature” in America (Masson et al. 1946, p.3).

It is interesting to think about the way modern artists perceived this work compared to the line of thinking from Lombroso and others, who sought to equate mental illness – a pathological condition – with genius or innovation. For Ernst, Klee, and other artists, insanity represented freedom from culture and convention, and therefore was something to aspire to, not to denigrate (Porter 1996). Chagall stated:

I am against the terms ‘fantasy’ and ‘symbolism.’ Our whole inner world is reality perhaps even more real than the world of appearances. If we call everything that appears illogical ‘fantasy,’ ‘fairy-tales,’ etc. we really admit that we do not understand nature. (Masson et al. 1946, pp.33–34)

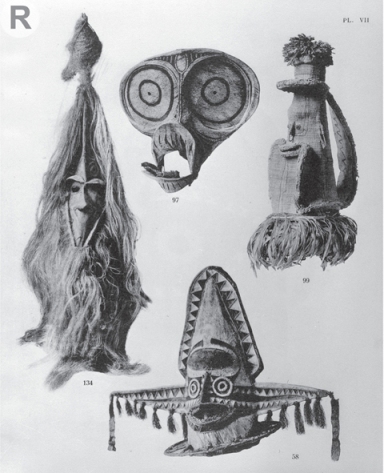

Figure 2.5 Collection André Breton et Paul Eluard, Sculptures d’Afrique, d’Amérique, d’Océanie, Auction catalogue, Paris, Hotel Drouot, 23 July 1931, Pl. VII. fig. 58: “Dukduk” mask, British New Guinea, fig. 97: Mask, head of fantastic animal, New Britanny, Baining, fig. 99: Mask, conic shape, New Britanny, Sulka, fig. 134: Mask, New Hebrides. Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

For the Surrealists, madness “was a metaphor for absolute freedom” (Rhodes 2000, p.84), to be thought of as “a creative rather than a destructive condition” (Cardinal 1972, p.15). Once again, we see how words and terminology change depending on social and experiential context; hence, Lombroso and the Surrealists saw a similar connection between mental illness and creativity, the former concluding that this was therefore pathological, while the latter saw it as the ultimate release from cultural constraints.

Surrealists explored the totality of man’s inner and outer selves – but not just within their own work. For the Surrealists, getting the viewer to participate in this process by engaging all senses in the process of viewing, receiving, and responding to a piece would accurately encompass the entirety of the “art” process, from creation and beyond. Therefore, Surrealist exhibitions were designed to be multisensory, creating an encompassing environment of mystery in which the viewer was to find – and experience – him or herself (Buchloch 2014; Celant 1996). Art was no longer just something to hang on the wall, but instead, something to be experienced by the perceptual process, both in making and in viewing.

An example of the different forms this took can be seen in Piet Mondrian, who was one of the first painters to experiment with different size and structure of canvases, eschewing traditional frames for his pieces and choosing to hang some at angles (Masson et al. 1946). Mondrian, like his peers, believed that: “The first aim in a painting should be universal expression” (in Masson et al. 1946, p.36), so his way of communicating differently in a universal language would achieve both a physical manifestation of his process of perception, as well as a forced exploration of response on the part of the viewer. To go back to our initial discussion of art as an expression of idiosyncratic visual language, Mondrian used a format that could be identified – oil on canvas on a wall – and subverted it to cause a reaction in the viewer that forced them to engage with the work in new ways.

As with his peers, Breton – who would also be influential in Dubuffet’s art brut – saw mental illness as stripping down the barriers that block socialized humans from getting in touch with their sought-after inner creativity: “Here the mechanisms of artistic creation are freed of all impediment” (Breton, as cited in Cardinal 1972, p.15). While Breton greatly praised and appreciated the work of artists with mental illness, he also supported classifying them as different; however, this again from the perspective that rather than thinking of madness as a negative, it was seen as a positive attribute that artists should aspire to (Thévoz 2001).

In a somewhat parallel fashion to psychoanalysis, Breton experimented with “automatic writing” in order to express what he deemed his unconscious, free of the limits of acceptable thought and behavior. However, as Gibson (1987) illustrates, while it is common to consider psychoanalysis as one of the influencers of the Surrealists’ interest in and use of the unconscious, it was actually an earlier form of therapy being practiced in France that was the greater influence – what was considered “dynamic psychiatry,” a form of treatment in practice since the 19th century. As opposed to the psychoanalytic emphasis on the role of and relationships of the analyzer and analyzed, dynamic psychiatry was birthed from an interest in spiritual mediums, where the patient/medium was the source of and receptor of the inside being expressed outward. To summarize the difference between psychoanalysis and Surrealism, while Freudian psychoanalysis sought to connect unconscious expression in consciousness with a patient’s past, the Surrealists sought to express the unconscious for its own sake.

In the preface to the catalog for the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, Breton summarizes Surrealism’s efforts as “having succeeded in reconciling dialectically these two terms which are so violently contradictory for adult man: perception, representation; and in bridging the gap that separates them” (Breton 1936, p.8). After the advent of photography, it became crucial for artists to find something new to represent visually, and so, the focus for Surrealists became on the mechanisms within the human that guide both creation and reception of visual objects.

Surrealism was also crucial in the establishment of art therapy as a discipline (Hogan 2001), an element sorely missing from the majority of histories of the field. It is in England that perhaps the biggest crossover between Surrealism and art therapy occurs. In a lecture at the above mentioned exhibition of 1936, Hugh Sykes Davies discussed art as an expression of the unconscious, an idea that both psychoanalysis and Surrealism were exploring (Hogan 2001). Davies, along with Roland Penrose and Herbert Read, also responsible for planning and executing the event, would continue to highlight how art history and the history of outsider art and art therapy are entwined. Between 1947 and 1983, Penrose was involved with the Institute of Contemporary Art, first as chairman, then as president. In 1955, he held an exhibition of patient work which was grouped according to categories such as “symbolism in psychotic painting” and “interpretation of visual imagery”; in the exhibition’s catalog, he would go on to highlight some of the prevailing thoughts on “patient art” from both the fine art and psychiatric fields, namely, “whether the distinction between normal art and psychotic art was justified” (Hogan 2001, p.102). After all, at a time in art history when artists were embracing the labels of other and madness, how was it possible to distinguish a “sane” process from an “insane” one? As we have seen, Read held close ties to Jung, and in Chapter 3 he will be discussed in-depth regarding his contributions to art education.

Outside of England and Paris, other modern artists were also seeking out the “other.” German Expressionism was highly influenced by the idea of the “primitive”; but, rather than pictorial space, the Germans looked towards tribal arts as giving “the possibility of emotional release from a sometimes excruciating discontent, feeding a spiritual, if sometimes quasi-pagan, longing for freely externalized feeling” (Masheck 1982, p.94). This search for an expression of feelings led German artists to look for ways to experience tribal communities, and their productions, first-hand; a main adoption of the Expressionists were woodcuts, and they executed them in a raw style, linking the medium to the use of wood in tribal cultures. Considering the “birth” of German Expressionism coincided with the Fauves in 1905–1906, it is no wonder that there were shared affinities between both for “new” “old” forms of expression (Haftmann, Hentzen, and Lieberman 1957).

The Die Brücke group, existing roughly between 1905 and 1913, made use of this influence from the “other” in overt forms. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner came into contact with an exhibition on the South Seas at a museum in 1904, and adopted many of the expressive qualities he found in these works in his process (Haftmann et al. 1957). Often thought of as “the richest in ideas, the most sensitive, and the most gifted” (p.46) of the group, it is interesting to note that Kirchner also suffered from mental illness. In 1917 he was admitted to a hospital in Davos, Switzerland, and while his work between then and his death is much celebrated, he committed suicide in June of 1938.

Wassily Kandinsky, along with Paul Klee, Franz Marc, and others, formed the “Blaue Reiter” group soon after; the name was used by Kandinsky and Marc for a 1912 book that “dealt with the nature of the naïve artist: peasant glass painting, old German woodcuts, and children’s drawings” (Haftmann et al. 1957, p.57). Kandinsky and Klee are particularly relevant due to their promotion of artwork from non-traditional contexts of creation, from schoolchildren to institutionalized individuals.

Kandinsky’s 1911 book, Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), drew heavily on the idea of universal creativity as an innate form of human expression, and illustrates why the work of modern artists sought to tap into this primal creativity. An interesting element of Kandinsky’s text is that he started to notice ways in which his artmaking was connected with art on a universal level. For example, he took a step beyond academic color theory, sharing general interpretations of colors based on feelings and subjective associations that could affect the creating and viewing experience (Kandinsky 1977, p.25).

Kandinsky is also an interesting split in the influence of what “primitive” meant in Western and Eastern Europe, and an example of how so many different groups of people have been labeled under the umbrella of outsider. While he worked predominantly in Munich, his early life and experiences in his native Russia with folklore and the artwork of peasants had attracted him with a simple use of form and color, hallmarks of style he would go on to use throughout his career (Haftmann et al. 1957). His use of these inspirations was personal: “Kandinsky was a Russian, and the symbolic language of the icon, the mystical splendor of the Orthodox Church, the variegated ornament of Russian folk art were deeply rooted in his sensibility” (1957, p.75), and helped inform his own expressive voice. However, we can again see how it is the grouping of a vast diversity of people and places as “other” that led to some of the contemporary problems with terminology and definition.

Klee was infatuated with everything from children’s art to the art found in asylums as a way of showing the raw and spontaneous creativity that he was seeking within his own work (Peiry 2001). The influence of non-traditional forms of creative expression on Klee is enough to fill its own book; for our purposes, it is his search for unrestrained creativity that is most applicable. In Klee’s view, the artistic ability of children was a reflection of the creative potential in man, but as opposed to dampening it with training and tradition – the effects of culture and education – Klee advocates for preserving this impulse of raw expression. From his journal notes in 1911–1912: “the more helpless they are, the more instructive are the examples they furnish us” (Klee and Klee 1964, p.266). Furthermore, Klee sees the same process at work in the art of people with mental illness:

Parallel phenomena are provided by the works of the mentally diseased; neither childish behavior nor madness are insulting words here, as they commonly are. All this is to be taken very seriously, more seriously than all the public galleries, when it comes to reforming today’s art. (Klee and Klee 1964, p.266)

Figure 2.6 Classical Grotesque, Paul Klee, 1924. Watercolor and transferred printing ink on paper mounted on cardboard. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984, www.metmuseum.org.

While modern artists sought out works from the “other,” there is also an interesting reverse effect on the public perception of primitive or tribal art that occurred based on what Rubin (1984) saw as misconceptions attributing influence to the work of modern artists where there is really only affinity (p.38). While Rubin perhaps grants far too much significance to the idea that modern artists were not, in many cases, directly appropriating the work of other cultures, this idea of affinity also led to misunderstandings of the original role and function of the tribal objects to a wider European public. Perhaps this is most evident in the misreading of African sculptures, embraced by the Expressionists as signifiers of inner turmoil, demonic possession, or other “scary” feelings – represented in works such as those of Munch. Because the Expressionists were interested in expressing the “uglier” side of the inner self, and they used the form, compositional, and structural elements that had affinities with African sculpture, the public began to read Expressionist meanings into African art – imbuing it with a ferocity that was not necessarily in sync with the context of its creation or meaning to its creator.

It is also necessary to comment on how imperialism helped proliferate the exposure and access to “primitive” art, and what it means regarding the perceived boundaries of what is inside and outside of culture. Germans Emil Nolde and Max Pechstein both traveled abroad, the former to New Guinea in 1913, the latter to Palau in 1914. Both locales were German territories; hence, the artists could travel “officially” and easy to a Germanized, yet “exotic,” land (Masheck 1982). On Nolde’s travels he celebrated “the absolute originality, the intensive, often grotesque expression of force and life in the simplest form” (as cited in Haftmann et al. 1957, p.34) he experienced in the art there, yet as with many of his contemporaries, he saw it through a Western/Germanic lens.

In fact, if we look at the adoption of what “primitive” means we can start to see a divide between Eastern and Western Europe, and international territories. England, Germany, France, and other areas could send artists to colonies in Africa and the South Pacific, and those artists would remain oriented by their own local cultures, customs, and country folk who resided and traveled there and who were the people in power. Western Europe’s idea of outside, therefore, was not actually that far removed from the idea of inside, given that these exotic locales were technically Western controlled and influenced.

What also emerged at this time was the attraction of the untrained European artist. These creators, typically labeled as primitive or naïve, were, ironically, the influencers of many modern artists, and some have since been “accepted” into a Western art historical canon. Wilhelm Uhde, collector of modern art, wrote frequently about Henri Rousseau and other “primitives” that he collected, including his 1947 work, Five Primitive Masters. Uhde in some ways leveled the playing field between modern and “primitive” artists by treating the latter in the exact same way as the former; through collecting, scholarship, and promotion.

Importantly, Uhde does include the background context of these artists when he writes about them; it is, after all, an important point to place these artists as “everyday” people at a time when there was a search for an art of the common man: “they had no education to speak of, no opportunities, no cultural stimulus, no funds” (1949, p.13). This mattered because it purportedly showed that the force to create within these artists was strong enough to overcome these limitations, perceived or otherwise, and that the normal man, the down-trodden poor man of an economically struggling Europe, was capable of producing great art.

Rousseau, who now holds an esteemed position in the history of modern art, was thought of as “primitive” because he was untrained and worked as a customs officer to support his family. However, Uhde’s relationship with him shows that he is, without a doubt, an artist, but also someone who benefited from assistance from the “inside.” As Uhde points out, while Rousseau didn’t live in a world of high-brow culture, he did seek attention from the public; “to him, fame was both necessary and inevitable” (p.26). Rousseau, more importantly, was far from the “Sunday painter” he is often erroneously labeled; Uhde knew first-hand that he lived and breathed his work – prizing it over everything else in his life.

Figure 2.7 The Repast of the Lion, Henri Rousseau, c. 1907. Oil on canvas. Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest Of Sam A. Lewisohn, 1951, www.metmuseum.org.

Rousseau’s subject matter, through Uhde’s descriptions, shed further light on the ways in which the artist used and conceived of his artwork. He did paint small canvas landscapes and other works for commissions, but he is best known for his large paintings of jungles and serene, otherworldly scenes. Uhde recounts how these canvases took up nearly all of Rousseau’s living space, and posits that through creating his fantasy worlds, he was, in a way, able to live within them – at least until they were sold.

Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut

With Jean Dubuffet, artwork created in non-traditional contexts – particularly institutions – finally began to gain appreciation outside of a circle of interested artists and psychiatric professionals. As with his fellow artists, Dubuffet was initially attracted to this work because of a growing disaffection with art’s traditional rubrics, and so was seeking out a greater connection to raw, creative expression to inform his own practice (Dubuffet 1988).

Like plenty of artists throughout history, Dubuffet was adamantly anti-culture, what he defined as a nebulous term:

Sometimes meaning the knowledge of works of the past (in addition, let’s not forget that this notion of “works of the past” is entirely illusory: what has been preserved represents only a very specious, limited selection based on trends that won acceptance in the minds of scholars) and sometimes more generally the activity of the mind and the creation of art. (1988, p.8)

The ambiguity of this definition is, of course, intentional in Dubuffet’s belief; by linking cultural products with scholarly preservation activities, the two concepts become united in the public mind: art is inherently related to the historical tradition that it exists within, defined by an academic elite, which reinforces the authority of culture. Individuals outside of this elite learn to appreciate what they have been told is worth appreciating, because it has been selected by a “more knowledgeable” group than themselves. What he revolted against was a perception that it was the cultural elite who were the only ones capable of deciding when an object could achieve the designation of “art.” When France established a Ministry of Culture in 1959, Dubuffet was devastated; culture was already subject to approval by an elite hierarchy, and now, the government would also have a voice in deciding what was worth preserving and celebrating (Dubuffet 1988).

Unfortunately, with the control of cultural designations squarely in the hands of everyone except the common man, Dubuffet believed that culture could be used in a similar fashion to religion, playing “the role of ‘opiate of the people’” (p.10). When culture is elevated to a level beyond the common man, the common man becomes driven by a “desire for acceptance within” (p.92) and so, follows culture’s “rules” to achieve this inner status. This mainstreaming of culture, in Dubuffet’s opinion, was like a chain that needed to be broken if true art and original creation were to flourish. The answer he supplied was for those already within the accepted culture – interesting given his status as an artist – to challenge the authority of it; a process of “deculturation” which would help shed cultural tradition.

The idea of assigning value, in a financial sense, to art products caused Dubuffet to see an undue emphasis placed on the objects as opposed to the creativity behind them: “culture feeds on product, not on production” (p.77). When an object is assigned the designation of “valuable,” this confers prestige and acceptance, elevating the creator to a hierarchical level amongst his artist peers. Finally, when value is granted, the object is therefore considered to be worthy of conservation, preservation, and in-depth study. The standard under which culture judges a work valuable is based on the perception of a work’s “beauty,” another idea that Dubuffet was understandably against, as it implied an opposite negative value judgment of “ugly”: “I believe beauty is nowhere. I consider this notion of beauty as completely false. I refuse absolutely to assent to this idea that there are ugly persons and ugly objects. This idea is for me stifling and revolting” (Dubuffet 2003, p.296).

Dubuffet believed that the most subversive moments in the history of art are not actually definable as such; if they have been preserved by culture, they have lost claim to the title. For Dubuffet, subversion “is at its height when only one person endorses it” (1988, p.86), yet it is the ultimate goal for true creativity. Culture, and all the attendant publicity and public recognition that approval within it brings, essentially “asphyxiates” the production of art motivated by the true inner creative process.

In Dubuffet’s view, as with many of his contemporaries, mental illness was a positive condition, a stimulant of raw creativity and evidence of the ultimate removal of the shackles of society. It was sociocultural factors that deemed what was sane from what was insane: “the clear cut ideas that we have of sanity and of insanity often seemed to be based on very arbitrary definitions” (p.112).

Hence, Dubuffet’s rejection of culture’s “approved” art led him to seek out a sort of antithesis – work created by individuals isolated from the mainstream. Dubuffet was inspired by early experiences with Prinzhorn’s work and collection, and his goals for art brut were laid out in an advertisement for the Compagnie de l’Art Brut, established in 1948:

We are seeking artistic works such as paintings, drawings, statues and statuettes, all types of objects, owing nothing (or as little as possible) to the imitation of works of art seen in museums, salons, and galleries. On the contrary, these artistic works should put human originality to use, along with the most spontaneous and personal inventiveness; they should be productions which the creator drew (both the invention and means of expression) from deep within, the result of his own inclinations and moods, free from the habitual means of creation, and regardless of the conventions currently in use. (Dubuffet 1988, p.109)

Dubuffet’s emphasis is always on a search for raw creativity – the potential for which exists within all people – but which is best manifest in the worlds of creators outside of traditional and academic influence. Some of his “discoveries” included Aloïse Corbaz (Color Plate 2) and Wölfli, and many are now considered to be “masters” of art brut.

In the early days of the Compagnie, Dubuffet staged exhibitions emphasizing the democratic nature of art and art appreciation. He hung as many works as would fit in the space, and even prohibited sales – a point of contention that would fester between him and later partners. Instead, Dubuffet sought to expose these works to a larger audience, not to turn them into cultural products that became part of the inner art world by assigning them value. While exhibitions of patient artwork at asylums had previously been held, Dubuffet’s shows identified the artist with labels of their name, and without any identifying criteria as to their diagnosis or disabilities (Peiry 2001). It is interesting to think about this move in an ethical context; as with Morgenthaler, because the artwork was being showed as art proper, using the individual’s name was actually more empowering and removed them from the too-common label of simply “patient.”

Dubuffet’s collection was embraced by a number of artists in Europe, and it received exposure to American populations for a brief period in the 1950s, when artist Alfonso Ossorio housed it at his Hamptons home. The period the collection spent in America turned out to be less fruitful than Dubuffet had hoped; he found no new artists – the first American was not added until the 1980s – and there was little interest from American artists and art world professionals in promoting the work. Likely an even bigger blow to Dubuffet was that the little recognition that the collection did draw in the US ended up being tied to his own art: “They were only interesting insofar as they were illuminating and helped to elucidate the French painter’s work and views” (Peiry 2001, pp.110–111). In 1962 the collection returned to France, leaving little immediate impact behind.

Dubuffet, in many ways, struggled with reconciling his desire to collect, catalog, and write about this work, with his repulsion at these activities when performed under the rubric of “culture.” For this reason, many of his writings are upfront with the idea that he is not fully comfortable with his activities, despite his goal of promotion. He also had trouble differentiating influence and appropriation of these works within his own oeuvre, as many critics have noticed (Foster 2001).

When art brut and the works that Dubuffet had championed began to attract attention in the larger art world, he also became increasingly more protective over their context of presentation. Curator Harald Szeemann requested some works by Henrich Anton Müller for an exhibition exploring ideas of machinery, and Dubuffet replied in a letter that he avoided placing works from the art brut artists in “group or comparative exhibitions (with didactic purposes)” (Fol 2015, p.144), refusing the request. Dubuffet wanted to expose and preserve this work, but keeping it out of the “art world” proper meant that he – and his Compagnie – were the inevitable cultural insiders who could control how and where the art was received. Unfortunately, this move may have contributed to keeping this work from being integrated into the larger picture of art history.

American Art and the Other

It took time for America’s cultural sense of self to develop and flourish; arguably it was not until the 20th century that an “American” art emerged. After the Civil War, there was more time to spend on intellectual and cultural inquiry, which fostered a more discerning class of critics and scholars, and hence, a better educated – and influenced – public (“The Conditions of Art in America” 1866). By the turn of the 20th century, with the birth of modern art in Europe, it is no wonder that the rapid development of an American artistic culture precipitated a look elsewhere for new forms and a unique national style.

The initial American artistic tradition was in line with the ideals set by centuries of European artists. Grand landscapes and portraits of traditional beauty were displayed to show how “talented” American artists were according to a Eurocentric tradition (“The Conditions of Art in America” 1866). Unsurprisingly, as with Europe, given a changing sociocultural environment, both art insiders and the newly-indoctrinated art appreciating American public turned to alternative forms of artwork that were more representative of the “common” experience by the turn of the 20th century.

While the European context for the flourishing of outsider art, and the roots of art therapy, consisted mainly of a focus on the works of “primitive” tribal cultures and artwork from patients in asylums, in America, artists seeking new forms of expression looked to American folk art and Native American Art. In the 1920s, the artists’ colony in Ogunquit, ME saw folk art as “a means to a less academic, more personal and emotional mode of representation” (Danto 1997, p.33); in the same vein as their European counterparts, they saw potential for a more authentic form of creativity in work not restrained by adherence to traditional ideas of beauty.

America’s folk and native art also had an effect on European artists who spent time in America. Kurt Seligmann, who spent almost ten years in the States during the 1930s and 1940s, was already a collector of primitive work and a donor to Paris’s Musée de l’homme of both Native American and Pacific Northwest Inuit art. For him, the natural American landscape and the works of indigenous people became a primary source of influence (Masson et al. 1946).

For whatever art history may be lacking in America, the rapid rise of the gallery system, particularly in New York, meant that from a relatively early time, attention was paid to works considered outside of what conventional traditional aesthetics and art meant. When collectors and artists started paying attention to folk art in the early 1920s, it quickly surged to national popularity as a work that reflected the spirit and development of the country itself.

It is the societal changes that rapidly proliferated in 20th century America that made the search for “common” man’s artwork all the more a necessity for cultural survival in challenging times. Metcalf and Schwindler (1990) saw folk art as being embraced by a larger public in the earlier part of the century because it formed a link to an American past and tradition – “the contrasts between modern society and the pre-modern world” (p.12). By the 1930s, the effects of the Great Depression left very few Americans wealthy enough to purchase art, and hence, folk art also became a financially and physically accessible form of art (Rexer 2005).

One of the first American shows to focus on folk art was 1924’s Early American Art at the Whitney Studio Club, curated by Juliana Force. This expansive show, held in Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s downtown space, brought together “pieces lent by modern artists and Force, among others, and included everything from paintings to bone carvings” (Lipman and Winchester 1974, p.10). The significance of Whitney’s support of this work early on should not be missed; she sought out the other in art – the avant-garde, the unrecognized – and so her exhibition notes just how important this work was in an art historical context that was not defined by rigid barriers. When the Whitney Museum opened in 1930, Force, as curator, accessioned a number of folk artworks into the collection. A catalog from a later show reflected the importance placed on this work from an early date: “A feature of American art from its beginning in the 17th century has been the wide prevalence of folk art, and its frequent high quality” (The Whitney Studio Club: American Art 1900–1932 1975, p.17).

Without funds to purchase art, and a severe break in the ability for the common man to relate to the polished traditional artwork of the past, searching for something of the people for the people became a priority for artists, collectors, and critics alike. Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, founded only years before the start of the Depression, was a true visionary in representation of an emerging multifaceted idea of art.

In 1929, Holger Cahill partnered with Halpert on a space above the Downtown Gallery – the American Folk Art Gallery (Robbins 1994). It was this venture that was most profitable during the years of the Depression, but Halpert’s shows also set up an inclusive way of showing and promoting the work of folk artists without relying on an inside–outside dichotomy. Cahill himself was incredibly instrumental in building the idea of an ‘American Art’ – inclusive in all its forms, and would go on to hold a number of exhibitions on folk art at the Museum of Modern Art, including the 1932 American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man in America 1750–1900 and the 1938 Masters of Popular Painting.

In the catalog introduction for the 1936 show New Horizons in American Art, Cahill showed his preference for art that speaks to the social condition of the common audience: “art is a normal social growth deeply rooted in the life of mankind and extremely sensitive to the environment created by human society” (p.9). As head of the Federal Art Project (FAP), Cahill was instrumental in literally bringing artwork to the lives of people who could not access it, through large-scale murals, placement of pieces in municipal centers, and support for artistic production outside of metropolitan centers. Cahill’s goal for the FAP was to help foster an American art – which meant production and appreciation could not be limited to a certain class in the Northeast. Therefore, his project sought to encourage production of art in regional areas, and he would go on to promote this work in exhibitions such as the one held at MoMA in 1936.

Cahill continued to hold shows at MoMA that focused on a democratic view of art that broadened the definition of the term. The inclusion of folk art in a museum of modern art shows how it was seen as an intermediary link that could connect the everyday man with the cultural production and institutions he had previously been alienated from. Additionally, we once again see the recontextualizing of objects from their original setting into the role of art by placement in a museum or gallery context, but also an early call to rewrite art histories in an inclusive manner.

For art historians and critics, folk art became a way of closing the gap between the common man and creative expression. In a 1935 article, critic E.M. Benson placed the responsibility for this gap between man and art as being propagated by critics and academics throughout history, who had sought to “direct the seeing of others” (p.71), placing artists in particular “styles” and “isms” in order to control the experience of the viewing public. Unfortunately, in Benson’s opinion, by doing so, too many critics have missed the important fact “that artists separated by hundreds of years in time and thousands of miles in space could, despite differences in race, culture, zeitgeist, have produced works of striking formal, human and psychological similarity” (p.71). Hence, histories based on regional or temporal formalities could be expanded beyond simply linear considerations. Benson’s theory is applicable to an understanding of the principles behind art therapy as well: he notes that each artist must grapple with the culture and time they live in, overcome barriers to creation, and solve problems both formal and conceptual in order to successfully present their vision; although they may create in different times or places, this same process of creation is followed by artists everywhere. In a sense, this speaks to contemporary art critics like Jerry Saltz (2016) who have renewed the call for a view of art history that includes all creators, not restricted by timeline or region.

It was not just New York City’s art world that was attracted to this work. In 1932, The American Magazine of Art mentions the arrival of an exhibition of American Folk Art in Buffalo; the work that had so enamored New York’s scene for the last couple of years, “representing so much of America’s most genuine art expression” (“American Folk Art—Buffalo” 1932, p.122), was finally extending outwards of the coastal cities that had “discovered” it anew. In 1934, the magazine announced the arrival of the first “national” folk art festival, to be held in St. Louis. A “comprehensive” look at this work, the announcement states that “All American folk art groups will be represented, including, necessarily, the Indian and the Negro” (“National Folk Festival St. Louis” 1934, p.212). Incorporating craftwork, theater, music, and dancing, the festival celebrated “the simple, earthy arts of the people themselves” (p.212). However, it also shows how sociocultural conditions ultimately influenced what was labeled folk – or that which was somehow different from a mainstream art. For a large part of the 20th century, this meant that boundaries could unfortunately be drawn between “types” of art based on a creator’s race, gender, or class status.

However, this surge in popularity of folk art illustrates how social contexts can shape the recognition, appreciation, and consideration of certain types of objects. Now that the entire country was suffering from destitute means, there was no market to purchase or commission oil portraits, and the American people of the 1930s were unable to connect in a meaningful way to art productions of times – and circumstances – past. What was inside culture had shifted to mean something different at times of struggle.

The 1960s and Beyond: “Contemporary Folk Art”

By the middle of the 20th century, folk art – and all that the term came to encompass – started to become its own area of critical focus within the art world. Ardery (1998) sees an idea of a “contemporary” folk art as rising out of a confluence of societal, global, and industrial changes, culminating in the period between 1965 and 1985. Folk art was an antidote to the growing commercialism in America of the 1960s, and for collectors and scholars, this work became both the embodiment of America’s regional craft culture and one of the “contemporary heirs to modernism, as an innovator” (p.3).

Of course, there is also a surge in the international “insider” art world seen in the 1960s, at a time when commercialism fused dangerously close with the world of so-called fine art. Seeking funding from major corporations or government entities, insider artists were focused on how to move up the ladder into a higher echelon of elite; on the opposite end, so-called “folk” artists were simply interested in creating their work (Ardery 1998).

There is another thread of American history addressed through folk art, that of the regional tension between the north and the south. While the center of the American art world has undoubtedly been New York City, for the first half of the century, artists from the South would only come to light if the artist moved to or traveled to New York. Hence, we see the start of the outsider art “system” as it is now understood, precipitated on the bringing “inside” – by someone who is already there.

By the time of the establishment of New York’s Museum of American Folk Art in 1961, there was a steady stream of attention being paid to artwork created outside of the art world mainstream. Between 1970 and 1974, 30 exhibitions of folk art were held, between 1975 and 1979, a staggering 64 were held, 80 between 1980 and 1984, and 125 between 1985 and 1989 (Ardery 1997).

As Ardery notes:

Marked initially by its “specialness”, folk art in the 1990s has been incorporated like so many rarities before into established cultural institutions – museums, galleries, universities – reflecting both the extent of those institutions’ embrace and the difficulty of sustaining alternate foundations for artistic understanding and regeneration. (1998, p.4)

She uses the work and life of artist Edgar Tolson to show the impact of this process on the folk art creator, and the issues inherent with translating work from a “folk” to a “contemporary” art context, seeking:

To portray him as a complex, talented man, who, for a variety of reasons, perpetuated, changed, and betrayed the local culture into which he was born and found a place he could not entirely choose or enjoy in a larger, national culture as well. (Ardery 1998, p.5)

Again, we see continuums of the purpose of the product – both to the creator and to the viewer – but also how boundaries of insider and outsider are fluid, to a point.

The Late 20th Century: Notable Exhibitions

There were a number of important international shows that included the works of non-traditional artists in the latter half of the 20th century, each shaping future perceptions of this work in one way or another.

Legendary Swiss curator Harald Szeemann is responsible for some of the earliest examples of placing art brut onto a level of aesthetic value with other forms of modern and contemporary works. As director of the Bern Kunsthalle, he held a 1963 show, titled Bildnerei der Geisteskranken – Art Brut – Insania Pingens (Artistry of the Mentally Ill – Art Brut – Markings of Insanity), including work from Prinzhorn’s collection as well as artists from institutions in Switzerland and France (Fol 2015); of course, his choice of title is significant given that it was a nod to Prinzhorn. Szeemann continued to include self-taught and art brut artists in his shows at the Kunsthalle until his departure in 1969.

In 1972, Szeemann included Adolf Wölfli in Documenta 5, an internal exhibition highlighting the most exciting examples of contemporary art productions. Szeemann used the opportunity to address the boundaries and marginalizing effects of the cultural institution, exemplifying his point with examples of the work of self-taught artists.

Szeemann maintained this interest in showing and sharing art brut for the rest of his career. In fact, in the late 1990s he was asked to organize a traveling show of “self-taught art” for the Philadelphia Museum and the American Folk Art Museum; he recounts, “I told them to drop the title ‘self-taught’ and just say ‘art,’ not to be afraid of presenting them alongside the greatest since obsession had no borders” (as cited in Fol 2015, p.151). In Szeemann’s vision, constraining the exhibition to simply those artists reduced to the self-taught label would do all artists an injustice; for him, it was equally as important to have the work of Thornton Dial in conversation with Jackson Pollock as it was to place him amongst other “self-taught” artists (p.151). Ultimately, Szeemann ended up leaving the project.

The curators of the 1974 Whitney Museum exhibition The Flowering of American Folk Art: 1776–1876 limited their requirements for inclusion in the show to works created between the “prime years” of folk art, 1776 to 1876; in their view, with the rise of the industrial era, “this art had reached its peak” (Lipman and Winchester 1974, p.6).

Even with this show, that places artwork in a specific time and place – a period of 100 years in America – the curators cannot provide a definition or term that effectively encompasses all of the work:

No single stylistic term, such as primitive, pioneer, naïve, natural, provincial, self-taught, amateur, is a satisfactory label for the work we present here as folk art, but collectively they suggest some common denominators: independence from cosmopolitan, academic traditions; lack of formal training, which made way for interest in design rather than optical realism; a simple and unpretentious rather than sophisticated approach, originating more typically in rural than urban places and from craft rather than fine art traditions. (Lipman and Winchester 1974, p.6)

In a sense, their definition of these works of American creators, typically white, free men and women sharing a new experience of a new country, is again based on what it is not – adherent to formal traditions. Lipman and Winchester even admit to settling on the term folk art for “convenience,” suggesting instead that perhaps it should be interpreted as “art of ‘the folks’” rather than “of a folk” (p.9). What the curators do note is that whatever the work is referred to as or defined as, it is undeniably important in the context of both art and American history: “I believe it was a central contribution to the mainstream of American culture in the formative years of our democracy” (Lipman and Winchester 1974, p.7).

1982’s Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980 at the Corcoran Gallery brought together Black artists from the South, and while it is highly significant in that it brought this work to visibility, the show itself presented and perpetuated some of the problems that continue to plague the idea of “outsider.”

The preface to the exhibition catalog foreshadows the problems that the exhibition raises: “This art will probably disturb many viewers because it is so different from what we usually find in art museum collections” (Livingston and Beardsley 1982, p.7). Already there is a judgment placed on this work as “other” – both other from what exists and other in terms of the expected audience. If the expectation is that this work will be seen by audiences new to it that means that the community it comes from will not see it and hence, the dichotomy of inside and outside continues in an institutional and sociocultural sense.

The curators seek to handle this work with the utmost respect, but it shows how even in the 1980s race, socioeconomic status, and biography were rubrics under which objects could be labeled as “art” – or not. While the creators in the Corcoran show are referred to as artists, their processes and similarities are reduced down to a shared geographic region, social role, and race. The curators almost fix these artists in a state of limbo, in which they are both intrinsically connected to but also isolated from both a mainstream and from each other: “It is an esthetic paradoxically based in a deeply communal culture, while springing from the hands of a relatively few, isolated, individuals” (Livingston and Beardsley 1982, p.11). What is ironic is that it is shows like Black Folk Art that place the ultimate focus on the creator’s biography, and place the work in a position in which it is susceptible to be considered for its “anti-artness,” in opposition to the normal, despite the intention of celebrating and promoting the artwork on its own.

In 1992, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art held Parallel Visions, a show in which curator Maurice Tuchman paired mainstream and outsider artists, as “a way of shedding light on the influence exerted by Outsider Art on the development of twentieth-century art” (Peiry 2001, p.253). While well-intentioned, Tuchman’s show lives on as a curatorial low-point in showing outsider work, as it was felt that the work was only being legitimized to the public based on the affinities it shared with “insider” art.

Also in 1992, in preparation for the establishment of the Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, MD, the United States Senate “passed a resolution stating: ‘Visionary art should be designated a rare and valuable national treasure to which we devote our attention, support, and resources to make certain that it is collected, preserved and understood’” (Fine 2003, p.248). The following year, Sanford Smith established the Outsider Art Fair, which would allow for these works to have a voice within the “pulsing heart” of the contemporary New York art scene (Fine 2004). Along with steadily rising sales – and prices – Steve Slotin introduced “Folk Fest” in Georgia in 1994, bringing 70 dealers and 10,000 collectors together to buy and sell art, and also started a biannual Georgia auction that continues to receive attention.

As momentum picks up in public interest of outsider art, it is growing increasingly common to see it placed within a contemporary or modern context – with and without additional labels. The 2013 Venice Biennale, curated by the New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni, was framed in a “language” of art brut or outsider art, without being explicitly labeled as such. Titled The Encyclopaedic Palace, a name taken from a project of visionary artist Marino Auriti, Gioni’s Biennale included everything from the work of Augustin Lesage to Carl Jung’s masterpiece The Red Book (Fol 2015). What made this Biennale stand out was that it gave work from non-traditional contexts contemporary and historical legitimacy without needing to explain why – Gioni allowed the work to connect with contemporary voices through international curatorial pairings. As Marazzi (2014) explains, Gioni’s curation:

led him to ignore the mainstream of contemporary art, praised by influential critics and valued in the art market, to give room to the often self-referential obsessions of isolated artists, to maniacal collections of objects as expressions of a repetitive convulsion, to a variety of forms as a sort of ‘maps of the mind’ of the author. (p.279)

Today, artwork from some of the best-known artists can be seen in major auction houses and the top art fairs around the world, in addition to specialized events. Curators like Gioni continue to explore non-traditional contexts of creation and objects in both institutional and commercial settings. A later chapter will explore how contemporary artists and galleries have further blurred the line between what is inside and outside, in addition to the lines between art therapy and contemporary art.

Surveying the history of art allows us to see how the continuums traced throughout this book reappear time and again. Of course, the idea of what constitutes art changed rapidly throughout history, negotiating boundaries of convention and innovation. Furthermore, in the work that was once considered “primitive” we see how objects can occupy different positions on these continuums based on who is viewing them. For the original creators, the work held meanings based in ritual or aesthetics; when it was resituated in ethnographic museums in Western culture it became a source of information; when it was again resituated in art museums it assumed (or resumed) a position as a work of art. The product itself negotiated roles of use after its creation, again affected by who was viewing or presenting it.

We also see how continuums of sick and healthy – particularly when it comes to mental illness – often stem from the same lines of inquiry as those traced in the previous chapter, but they are received in an entirely different way from an audience of artists. The Surrealists embraced the idea of mental illness, and Dubuffet prized it as the ultimate renunciation of culture, a giant leap from the ideas of degeneration and pathology of Lombroso and Nordau.

We see how the same objects and creators can hold different positions on these continuums depending on the social context in which they are received, the experiences of the viewer, the passage of time, and a host of other factors. When one starts to consider contemporary works of art, the borders that once framed these continuums are blown apart.