“CONDITIONS ARE QUIETER at Groveton than they have been for some time,” the Democrat reported in July 1917. “One carload of strike-breakers has left town and Charles Kelley of Colebrook has been appointed superintendent of police. This combination has worked to stop some of the disorder that was creeping out at intervals. . . . There have been occasional records of assault that resulted in police hearings. In one instance a shot was fired and the offender was held for aggravated assault to await the grand jury.”1

The longest strike in the Groveton paper mill’s history had begun on May 10, 1917, five weeks after the United States entered World War I. Four hundred and fifty striking mill workers, members of Local No. 41 of the International Brotherhood of Paper Makers and Local 61 of the Pulp Sulphite Workers and Mill Workers Union, shut down the Odell mill. The Advertiser’s correspondent predicted a short strike. A week into the strike Odell agreed to two of the strikers’ three major demands: wage increases and an eight-hour workday of three shifts to replace the eleven-hour day shift and thirteen-hour night shift. Willard Munroe, co-owner and manager of the mill, who had moved his family from Maine to Groveton when the strike began, refused to recognize the union, vowed to keep the mill closed for a year rather than yield, and imported Boston police officers to guard the mill and village.2

The union blamed the strike on management’s refusal “to do business with their employees as men. . . . These men had been working for the Odell Co. eleven and thirteen hours for years at starvation wages.”3 In the first week of the strike, one hundred mill workers and their families left town for work in Fraser’s Madawaska paper mill in far northern Maine.

While strikers, led by a band, paraded around town to honor a visiting union leader, the mill began to import strikebreakers. The Paper Makers Journal, published by the United Brotherhood of Paper Makers, alleged that Odell had brought in a number of carpenters from Lewiston, Maine, who were members of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, “under the protection of imported gun-men and so-called detectives.”4 The strikers were furious Odell had granted raises and an eight-hour workday to scabs after denying them to longtime workers.5

Mickey King’s grandfather told him about the strike: “There was this woman, Mrs. Lavoie; she was very outspoken about the scabs. I guess she had gone to church with a buggy, and someone had said something, and she hollered, ‘You scab.’ And she took the horsewhip to him, sitting in the buggy. She didn’t get him real good, but it made them angry. She was hanging out clothes, and they shot at her a couple of times.”

On August 19, an arsonist burned one of the mill’s barns on the meadow near the B&M Railroad bridge, below the Weston Dam, downstream of the mill. Four days later, the Associated Mutual Insurance Cos. sent H. B. McClune to survey the entire mill. (A framed copy of McClune’s handsome and informative floor plan hung in the mill’s office for decades.) At the end of August, James Prosser, a foreman in the fire room, was electrocuted in the coal yard. He left a widow and seven children.

Berlin mill workers brought their traditional Labor Day parade to Groveton, where “one of the largest holiday crowds ever seen” marched around town, enjoyed baseball games, speeches, a picnic, an evening band concert, a speech by Berlin’s mayor, and “a dance under union auspices in the Opera House.” The union reported that proceeds from the Labor Day parade had paid off all bills and netted a surplus of $104.36 that went to the strike fund. The Advertiser’s sympathetic report of the Labor Day festivities concluded: “Considering the feeling caused by the strike situation the day was remarkably free from disorder.” Nevertheless, it reported Everett Mayhew was stabbed in the left shoulder by a strikebreaker, and two or three other men were arrested “for minor offenses, or no offense at all, according to different views of the case.” The following morning while waiting for a train, Lee Whitcomb was hit in the face.6

In early October, the Advertiser reported that Numbers 1 and 2 paper machines were running twenty-four hours a day, while Number 3 was operating ten hours a day. The pulp mill was cooking sixteen hours a day, and all departments outside the mill were working overtime. The old blacksmith shop near the B&M tracks on Main Street, recently used by the mill as a mess hall for its scab force, was damaged by fire on October 21. Firemen were forced to break into the locked firehouse because, the Advertiser surmised, the key had been stolen. A second fire in the same location occurred later that day.

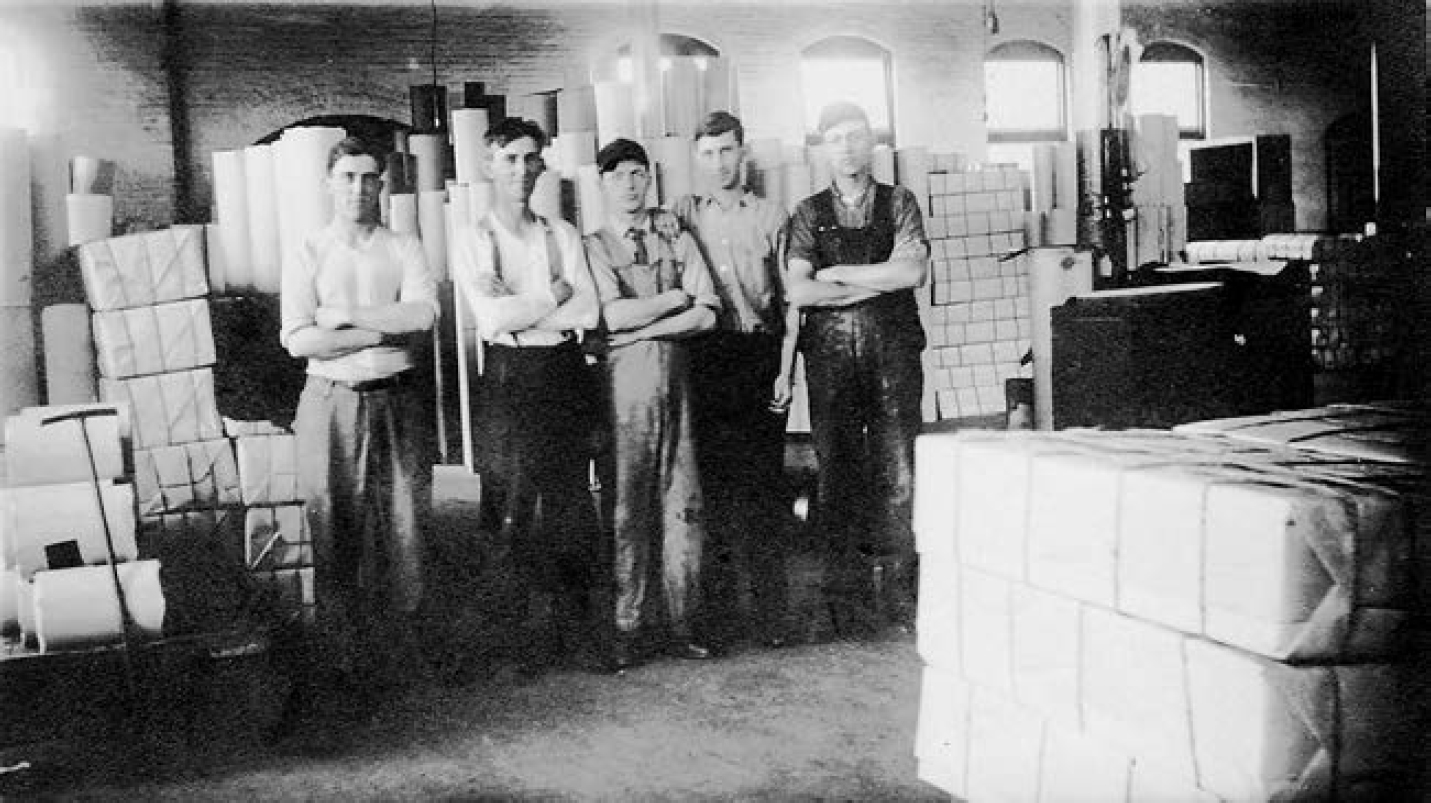

The shipping department crew in 1914 when the mill was prospering. (Courtesy Doug White)

Throughout the fall and winter, strikers and management traded barbs. The union accused the mill of blacklisting strikers trying to find work in other mills in northern New England. In December the Paper Makers Journal gleefully reported: “After a desperate struggle all summer, they failed to get the whole supply of logs from the river, and at present there is over ten thousand cords frozen solid in the upper river awaiting the spring freshet which will clean everything in the onward rush for the great waters of the Connecticut.” The following month, the union reported that the mill was suffering from a “scarcity of fuel as well as a scarcity of labor. What the management of the Company at Groveton expects to achieve by continuing the strike is beyond common sense reasoning.”7

Management charged the union with bad-faith bargaining and misuse of funds, while the union blasted the mill for buying up all available firewood and refusing to sell to non-employees. Early in December, the Advertiser reported that three families had moved to Groveton from Troy, New York, and that more than a dozen other families had moved to town in the preceding month to work at the mill. Three days before Christmas, an early morning fire in the mill’s stockroom caused $100,000 in losses. The 120-by-50-foot building was separated from the rest of the mill by a brick firewall.

The strike continued into 1918. Insufficient shipments of coal, presumably due to the war effort, forced the mill to operate only part time in early February. In March, E. H. Macloon, an executive with the Groveton Power and Light Company and chairman of the local Public Safety Committee, expelled Alfred Deering, who was accused of being an organizer for the IWW, the radical International Workers of the World union.

“There has been no change in the general strike situation,” the Groveton correspondent reported in the Paper Makers Journal in March. “The company are as hard up for help as they were last summer and the mill is in a desperate condition, in the machine room it looks like a junk shop, and from all reports they are junking the best part of it. The boiler room reminds one of a submarined fishing schooner where there had at one time, some human being lived and worked but at present they are all dead ones.” The correspondent claimed the pulp mill was in worse shape than even IWW saboteurs could have made it. Two digesters were “entirely out of business,” and the acid room was in terrible shape.8

The union reported that there was scant activity at the mill during the spring, and in August 1918, a union report from “Ratville, NH” noted that most strikers had found other work, and that the “large machine,” Number 3, had not been in operation for eight weeks. Thereafter, the strike continued, albeit at a low key. The Paper Makers Journal reported in September 1919, “At the present time we have no expenses, but the strike is still on.” Sometime before June 20, 1920, the strike had been called off.9

The mill owners never achieved the sort of control over the lives of their employees owners of classic company towns achieved, but Odell’s managers took several steps designed to weaken the threat of a well-organized labor force. Odell had been operating a company store in the old Soule store since about 1907. The October 1917 issue of the Paper Makers Journal reported: “The Company here has a soup house for their Boston rats, where they are fed like cattle and housed on the same plan the company hogs are, every hog for himself. . . . We call them the union scabs from Kennebec.”10 The following year, the mill constructed single-family houses on Odell Park for employees to rent.

Bitterness over the strike festered for decades. Jim Wemyss Jr. encountered it in the late 1940s: “I can only tell you one thing. It was like the Civil War in the United States. Brothers against brothers, and sisters against sisters, and mothers against their daughters. It did a terrible thing to this town because some were mad that the mill was on strike, and some wanted the mill on strike. It’s a town here. Just one town. They never got over that. I even had that thrown at me twenty-five years later. That’s when Willie Munroe became famous.”

In 1900, Willard Munroe and a group of United States and Canadian investors had formed the Brompton Pulp and Paper Company that owned mills in Vermont, New Hampshire, and the Sherbrooke, Quebec, area. Groveton’s Odell mill operated independently until it merged with Brompton on January 9, 1919, possibly as part of its strategy to defeat the union and end the strike. Brompton promptly changed the mill’s name to the Groveton Paper Company, and the company store was renamed “Groveton Paper Company Inc. Store.”

Despite an infusion of Brompton’s capital, the mill’s fortunes did not immediately improve. The United States economy, and the paper industry in particular, were in a postwar recession that would persist throughout 1921. Construction of a new acid tower for the bleach plant suffered a setback when one of its elevators fell about eighty feet on May 13, 1919. The man riding on it was badly shaken, but he escaped serious injury. A lightning fire on June 16 destroyed the mill’s power plant on the site of the old Weston Sawmill. It was immediately rebuilt. An estimated crowd of three thousand to five thousand peacefully celebrated Labor Day 1919. A week later, the top of one of the mill’s smokestacks blew over in a heavy rainstorm.

Around 7:30 a.m. on May 21, 1920, a fire broke out in the approximately ten-thousand-cord pile of pulpwood. Within an hour, the top of the pile was “a mass of flames.” Eight buildings nearby caught fire and appeared headed for destruction despite efforts by local citizens and the fire departments of Groveton, Lancaster, and Berlin. Around noon, a heavy rain began to fall, allowing the firemen to turn their attention from the buildings to the pulp pile. Half the pulpwood was destroyed, and damages were assessed at $150,000.11

That summer, Brompton’s Groveton paper mill launched a biweekly newspaper for its employees called the Gropaco News. It featured insider jokes about the antics of various employees, information about the company’s finances, photographs showing the progress of mill construction projects, news of mill paper production, accident reports, articles on how to make paper, and photographs of mill employees. In its Christmas 1920 issue, mill general manager J. W. Bothwell wrote: “Despite the depressed condition of business throughout the country, our company believes that business will improve in the near future. . . . Our company is working and will continue to work, for the best interests of the community as a whole, as well as for itself. Our interests cannot be divided. As I said to you some time ago; what is good for our Company is good for Groveton and what is good for Groveton is good for us.”12

Eleven ironworkers who built the enclosed structural steel passageway that housed the conveyor that transported wood chips from the wood room to the digesters in 1920: who were these men? What stories they could tell. (George Vervaris Collection, courtesy GREAT)

The following spring, while paper mill workers throughout the country suffered wage cuts of 10 to 15 percent, the Gropaco News continued to exude confidence that Groveton would remain busy and prosperous. The new owners were investing large amounts of money to build a new wood room, a new boiler house, and a new generator building. The contractor for the brickwork and these new structures, U. G. Houston, had worked on the smaller brick chimney in 1891 and had superintended the construction of the 1908 brick chimney. He had also overseen the brickwork on the digester house, the screen room, the filter house, Number 1 finishing room, Number 3 boiler house, and the Brooklyn power plant that had been completed in March 1919. “Quite a record,” the Gropaco News observed.13

The mill also installed a new drum barker that could debark 175 cords of pulpwood in eighteen hours. Some woodsmen continued to spend the warmer months of the year peeling pulpwood and swatting blackflies and mosquitoes, but, increasingly, the mill purchased cheaper unpeeled pulpwood that it fed to the new barker.

Willard Munroe and Charles Wilson bought back the Groveton Paper Company mill and its timberlands and hydropower from Brompton in 1927. The mill was running all three paper machines and employed 400. Formerly it had employed as many as 550, but mechanization had eliminated 150 jobs from the labor pool. The mill used ten to twelve million gallons of water a day to make paper and steam.14

Throughout the Depression, the Groveton mill struggled to survive. It failed to pay its 1932 property tax bill of $31,005.82. Its 1933 bill also went unpaid. By 1934, it was able to scrape together the wherewithal to pay off its 1932 tax bill, and for the remainder of the decade the mill avoided foreclosure, but it remained two years in arrears. The much larger Brown Company, located in Berlin, twenty-five miles to the east, filed for bankruptcy in 1935.

Number 3 paper machine had been shut down owing to lack of orders in the early years of the Depression. Although business improved enough by November 1936 to keep two paper machines running, Number 3 did not restart. Shirley Perkins Brown recalled that throughout the 1930s, the mill ran sporadically: “[My father] was working probably four or five hours a day, maybe two or three days a week. The mill was in pretty bad shape. They were trying to give the older workers time, but it really wasn’t enough to survive on. They probably never worked more than fifteen hours a week.”

“Willie” Munroe attempted to mitigate the crisis by adding a fourth six-hour shift to employ more workers, albeit at reduced hours. John Rich recalled: “I’ve heard some of the old-timers talk about it. They thought it was a great thing. Everybody got a little money. I’ve never heard anybody say but what he was an awful nice man.”

On February 25, 1935, workers detected a gas leak in the boiler room. They put up a fourteen-foot ladder to the twelve-foot-high economizer stack, and Ray Kimball, forty-six, climbed up to turn the damper. Tragically, he was overcome by gas, and he fell from the ladder to his death.15 Franklin “Honey” Beaton, a star outfielder on the town baseball team, suffered body burns and gas poisoning. Edgar Vancure carried the unconscious man to a window; Vancure suffered severe burns when a hot pipe fell on him. On November 5, 1936, another leak, most likely chlorine gas, overcame several mill workers. The Democrat reported that Truman Tickey and Merle McKean were injured. A couple of weeks later, the Locals noted that Arthur Pinaud was receiving treatment in Stewartstown Hospital after being gassed at the mill.16

On December 7, 1936, Willard Munroe agreed to a 10 percent wage increase. Recently business had improved, and the four hundred mill employees had requested a 20 percent raise. “It was hinted that the machines would not be started on Monday if the wage increase was not granted,” the Democrat reported. Under the new agreement, the minimum men’s wage would be forty-three cents an hour, and the minimum women’s wage was raised to thirty-six cents. Paper machine tenders, the highest-paid union jobs, would earn eighty-eight cents an hour. Workers would receive time and a quarter for overtime and time and a half for Sundays and holidays.17

In the fall of 1937, the mill shut down for repairs to the Brooklyn Dam (the rebuilt Soule Dam), and a week later, the pulp mill shut down for repairs for a couple of days. In mid-November the mill was idled because of “slackness of orders.” The Locals correspondent added, “All trust it will not be for long.”18 The mill closed for a week after Christmas 1937, and in February 1938, the Democrat reported that one out of ten residents of Coos County was receiving some form of relief.19 Orders were again slack in early April, and only Number 2 paper machine was operating, while “much repair work is being done.”20

Charles C. Wilson, one of the purchasers of the mill in 1895, died in Lewiston, Maine, on August 28, 1935, leaving Willard Munroe Sr. as the last of the original Odell Manufacturing Company owners.21 Munroe’s health was failing, and in the winter of 1937 the Locals column carried regular updates on his condition. He died in Maine on June 16, 1938, at the age of seventy-eight. His brother Horace and son Willard N. Munroe Jr. continued to run the mill.

SHIRLEY PERKINS BROWN: THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES

Shirley Brown was born in 1927 in Madawaska, Maine, where her father, John Perkins, had moved soon after the outbreak of the 1917 strike. The family returned to Groveton in the early 1930s, and her father worked in the stock prep department.

A chlorine gas leak at the mill in the mid-1930s destroyed her father’s health: “My father was a beater engineer. Chlorine came into town in the big tankers, and one of those tankers sprung a leak. I’ve heard two versions of this. They evacuated everybody from the mill, and they needed two volunteers to turn the pipes off on this big tanker. Then the other story was he was in the beater room cleaning it, and they didn’t know that he was there. From that time, he became disabled. It burned all the tissues in his lungs and everything. He was guaranteed a lifetime job. They gave him a thousand dollars settlement, which in those days was just incredible. His lifetime job was in the water room, which is in the subterranean part of the mill, and he wore a gas mask to work because the tissues in his lungs were all burned out. Practically all of our life was taking him to the Veterans Hospital in White River and taking him home for a little while. He was an invalid; he died when he was fifty-nine. I was probably about six or seven [when the accident occurred]. I can remember they didn’t even take him to the hospital. He was unconscious, and they brought him home. During those times, there was no insurance, so if you got hurt in the mills, you were on your own.”

Following her husband’s accident, Lyse Perkins was forced to take a job at the mill. “That’s when [my mother] started working for women’s rights, because the women weren’t paid equal to the men,” Shirley said. “She was instrumental in getting the things for women that worked in the mill—benefits. We never realized what an important role she played in the mill. We were probably fourteen or fifteen, and she’d be going on these conventions and winning all these awards for her work, and still working in the mill. She worked with an ulcer on her leg. Her leg was bandaged all the time.”

Despite the hard times, Shirley recalled the simple pleasures of a Groveton childhood in the Depression: “Most of the people that worked in the mill lived in company houses. There weren’t that many privately owned houses. The farmers lived a lot better than the people in town. The Depression was so bad, we knew what it was to be hungry; we knew what it was to be cold. The Legion in town took care of an awful lot of people in this town during that time. They bought food. At Christmastime, I used to hate it because we knew we were going to get a long-legged union suit [underwear] full of apples and oranges. I think if it hadn’t have been for the Legion, a lot of people in this town wouldn’t have survived because they took care of people who were really having a hard time. I never knew we were poor. My older brothers and sisters said they never knew we were poor until they went to school.”

During the Depression a relief truck came to Groveton once a month. “That would be a big truck with boxes of canned goods and food, and the necessities, probably, toilet paper, hygiene and stuff. I always dreaded seeing the relief truck come to town. Nothing was handed out. They’d throw it out of the truck. Whoever caught it, got it. It was awful. Once, the truck was empty; they had one box of prunes left, and the guy hollered, ‘Who catches it, it’s theirs.’ I saw my mother and another woman rolling in the dirt over that. Fighting over that box of prunes.”

In a scene out of Dickens, children scrounged for coal cinders to heat their homes: “When you used to walk downtown, you’d get home, and you’d look yourself in the mirror, and you could see in your eyes and mouth, that everything was black and sooty [from the coal burned in the mill],” Shirley remembered. “Also, the trains burned coal, and then every once in a while, they would empty the coal tank onto the tracks. We would go out after we got home from school [with] big pails. We’d walk the tracks and pick up the coal cinderblocks. People would put those in their furnace. A lot of times there would still be gas left in the coal. They would blow up.” “And it would come through the grate and all over the furniture,” her sister Patricia Woodward added.

Poverty carried a stigma. Shirley recalled a time she brought one of her Christmas presents into school: “Going back to school in January, after the Christmas vacation, I brought an orange to school. Oh, my God, I was so excited, ‘I’ve got an orange for lunch.’ The principal said to me, ‘Where did you get that orange?’ ‘I got it for Christmas.’ She said, ‘You did not; you stole it.’ She took the orange away from me and gave it to her granddaughter who was in the same class as me.”

Another time, Shirley and her older sister were accused of stealing: “When we went to school, it was almost an attitude, ‘If you were poor, you were stupid.’ It’s bringing back a lot of bad memories. Some money came up missing in the school. I was in the second grade, and one of my older sisters was in the fourth or fifth grade. Anyway, instead of questioning any of the kids, they took my sister and I and undressed us because we might have the money in our bloomers. It was a nightmare, and all of the kids were calling us ‘dirty thieves.’ A couple of weeks later, they discovered that the doctor’s son had stolen the ten dollars. They didn’t do a thing because he was a status—the doctor’s son. My older sister, it hurt her so much more than it did me because I really didn’t realize quite what was going on.”

“It was a hard time for kids to grow up,” Shirley reflected, “but we had a lot of fun. My dad, as sick as he was, during the winter, we would skate on the river, and he would have this—I think it must have been a bamboo fishing pole. He would pull that and we would be all hanging on and screeching and yelling and having fun. We played games. Kids talked to each other then. Strange as it was, we were happy. We made our own happiness. We had a ball. It was the best years of our lives.”

The Groveton Paper Company shortly before James C. Wemyss Sr. purchased it in August 1940. He immediately changed the name to “Groveton Papers.” (Courtesy Greg Cloutier)