“THE WAR HAD JUST ENDED,” Jim Wemyss Jr. recalled. “Gas stamps, rationing and shoes—you were allowed two pairs of shoes a year. [Rationing] went off pretty quickly, but there wasn’t the supplies in the pipeline to make any difference. It was a tremendous revolution in this country after the war ended. A lot of women didn’t want to leave their good jobs. They were getting paid pretty good, and everybody was worried that some soldiers coming back wouldn’t have any jobs because the women wouldn’t give them back to them.” Old Jim Wemyss’s plans to modernize and expand the mill guaranteed abundant jobs for returning soldiers. Many of these hirees—“the class of ’46”—would remain at the mill for the next three or four decades.

Because of his responsibilities to his family, Ray Jackson was discharged before war’s end. He immediately returned to the mill. Soldiers were permitted thirty days off before they had to reclaim their prewar job. Len Fournier, discharged in January 1946, thoroughly enjoyed his free time: “[I was] full of piss and vinegar.”

Neal Brown’s father, Bud, was hired shortly after the war: “I don’t think there was a lot of mobility in those days,” Neal said. “You grew up; you were familiar with your surroundings, and you didn’t feel the necessity to go someplace else to check out the pastures to make sure they were greener on the other side. A lot of those guys never finished high school. They went into the war. They came out, and they had a lot of skills that they didn’t have when they left; they had the leadership skills; they had the work ethic skills; they had everything else that was highly regarded. Of the kids that I grew up with, every one of our fathers had served. They didn’t talk a lot about it, but we knew where they had been.”

Neal’s mother, newlywed Shirley Perkins Brown, recalled the postwar prosperity that allowed the Browns to buy their own house: “When Bud got out of the service and went to work in the converting plant, he was making $39 a week. We paid $2,000 for the house, and we paid $200 down and $13 a month. Some of those months that $13 came hard. Then the pay started increasing and benefits started coming in like life insurance and health insurance.”

The converting plant produced stationery and school supplies such as spiral notebooks, blue test booklets, and graph paper. Its rapid postwar expansion meant jobs for young women, including sixteen-year-old Irene Paradis Bigelow. When she received her first pay envelope, she was on top of the world: “You didn’t have to make out an application for work or anything. If they needed somebody to work, they hired you right there. When I went to work in there, oh God, it was fifty-two cents an hour and I thought I had the world by the ass with a downhill pull. I’ll never forget, Polly Sawyer had a store, and the first paycheck I got I went in and bought a red trench coat.”1

James C. Wemyss Sr. became head of the family paper mill business during the war when his father’s health began to decline. On April 17, 1946, James Strembeck Wemyss, age sixty-seven, died of a cerebral hemorrhage. His grandson revered him: “I had a very positive relationship with that man. To say he was like my father—he was. He and I, just he and I. He got along with the other grandkids. He was polite to them and nice, but he really, I guess, enjoyed my company as a young boy. He called me the Crown Prince. He wanted me to be head of these companies, and he made no bones about it.” “When my father walked down the street, they took their hats off,” Young Jim asserted on another occasion. “Not me, but they did for him. And my grandfather, definitely!”

After the war, prices had begun to rise steeply, and, all across the country, labor demanded significant wage and benefit increases to compensate for wartime wage freezes, lost work time due to prolonged military service, and inflation. In early 1946, most New England paper mills gave workers raises of at least fifteen cents an hour, even though labor contracts were not due to expire until June.

The average minimum wage then paid to a male mill worker in Maine and Berlin, New Hampshire, exceeded the Groveton mill’s rate by twenty cents an hour. In May, Local 41 of the International Brotherhood of Papermakers and Local 61 of the International Brotherhood of Pulp, Sulphite and Paper Mill Workers requested that Groveton also grant raises in advance of the termination of the labor contract. Following lengthy negotiations, Old Jim offered a ten-cent increase to be paid in three installments: five cents on June 1, 1946, three cents on September 1, 1946, and two cents on January 1, 1947. The six hundred Groveton mill workers rejected the proposal and called a strike on September 12, 1946. Jim Wemyss suggested the strike didn’t phase his father: “He said, ‘Everybody needed a rest after the war anyhow, including me.’”

The unions demanded a twenty-two-cent-an-hour increase; time and a half for Saturdays and double pay for Sunday; a Christmas bonus of forty hours for employees with more than five years’ service and twenty hours for all others; and increases in paid holidays.2 A representative of the International union stated: “The workers at Groveton are not asking any more than has already been granted and is being paid by employers elsewhere.”3

Old Jim agreed to the Christmas bonus but rejected the wage increase. Mill management suggested that Groveton workers, by working forty-eight-hour weeks, instead of the forty-hour weeks in the other mills, were actually being paid a sum “equivalent” to the weekly pay of workers in other New Hampshire and Maine mills. The union declined the honor of working six days for five days’ pay.4

The union also demanded that future contracts expire in June to keep Groveton on the same schedule as other mills in the region—and to accelerate wage increases by three months. Wemyss insisted on retaining the September deadline. That later date allowed Groveton Papers’ management to see what concessions the other mills had made; and it discouraged long strikes that stretched into November and December. As winter approached, workers on a tight budget became nervous about paying the winter heating bill. Electrician Herb Miles was friends with the Wemyss family: “I never was for strikes. I wasn’t a striking man. But when it come fall, Mr. Wemyss said, ‘They’ll be back when the weather gets cold.’”

While some strikers picketed, others found jobs at the Gilman, Vermont, paper mill twenty miles to the south; a few families picked potatoes in northern Maine. “My husband and I had gotten married in June,” Shirley Brown remembered. “The men picked potatoes on their hands and knees with baskets. We spent all our time trying to clean up the hotel because it was awful. It was not a happy time.”

During the second week of the strike, a small fire broke out in some bales of waste and scrap paper in the Number 3 paper machine room. Firefighters, including fifteen striking mill workers, quickly extinguished it. Fire chief Thomas W. Atkinson blamed “spontaneous combustion.”5 Because of the hard feelings during the strike, Dave Miles’s father grounded his teenage son: “My father just said, ‘Dark, you stay home. You don’t go down street.’ And I didn’t go down street.”

Jim Wemyss relished sharing the family version of how his father ended the strike: “Father didn’t give a goddamn if they went on strike. He cared, but he wasn’t going to take any bull from anybody. He was a very tough guy. I was going to college at the time, and the union couldn’t find him for about three weeks, and they came down to the college. ‘You’ve got to find your father.’ I said, ‘I don’t know where he is.’ I had dinner with him every night [laughs]. They said, ‘You’ve got to find him. We’ve got to talk.’ So I talked to him. ‘Oh,’ he said, ‘Tell them we’ll have a meeting at the Parker House [in Boston] next week.’ I set it up. They had some real tough guys from New York and Boston. Some of the men from the mill. Father walked in with a big paper bag of walnuts and a hammer. And he sets down and one of the guys starts making a speech, and my father is rustling in the bag, and takes out a walnut and positions it like this and ‘bang!’ Breaks up. And this guy is speaking, and he breaks another walnut, and finally, [someone] said, ‘Jim, are you listening?’ ‘Oh, yes, I’m listening.’ He [the union representative] said, ‘We’re not getting anyplace, are we?’ [Father] said, ‘No.’ He said, ‘Could we all have some walnuts?’ [laughs]. He opened the bag and said, ‘Now, this is the way it’s going to be, gentlemen [he thumps the table several times in cadence to “this,” “way,” “going,”“be”], or I can disappear again for another six months.’ That’s the end of it. That’s how he negotiated.”

The strike ended on November 1. All employees received an immediate twelve-cent-an-hour increase with another five-cent increase to take effect on March 1, 1947. Minimum wages were raised thirteen and fourteen cents per hour. Workers received three holidays with pay and three more, if worked, at time-and-a-half pay. In a victory for management, the contract ran until September, not June, 1947.6

Jim Jr. claimed the government paid for the strike: “Taxes were tremendous at that time to pay for the war. And we were making money during that period of time. I actually think the six-week strike, the United States government paid for the whole strike, because you didn’t have to pay any taxes that year. The strike didn’t financially hurt Father that much. And, he kept saying, ‘Don’t do it.’”

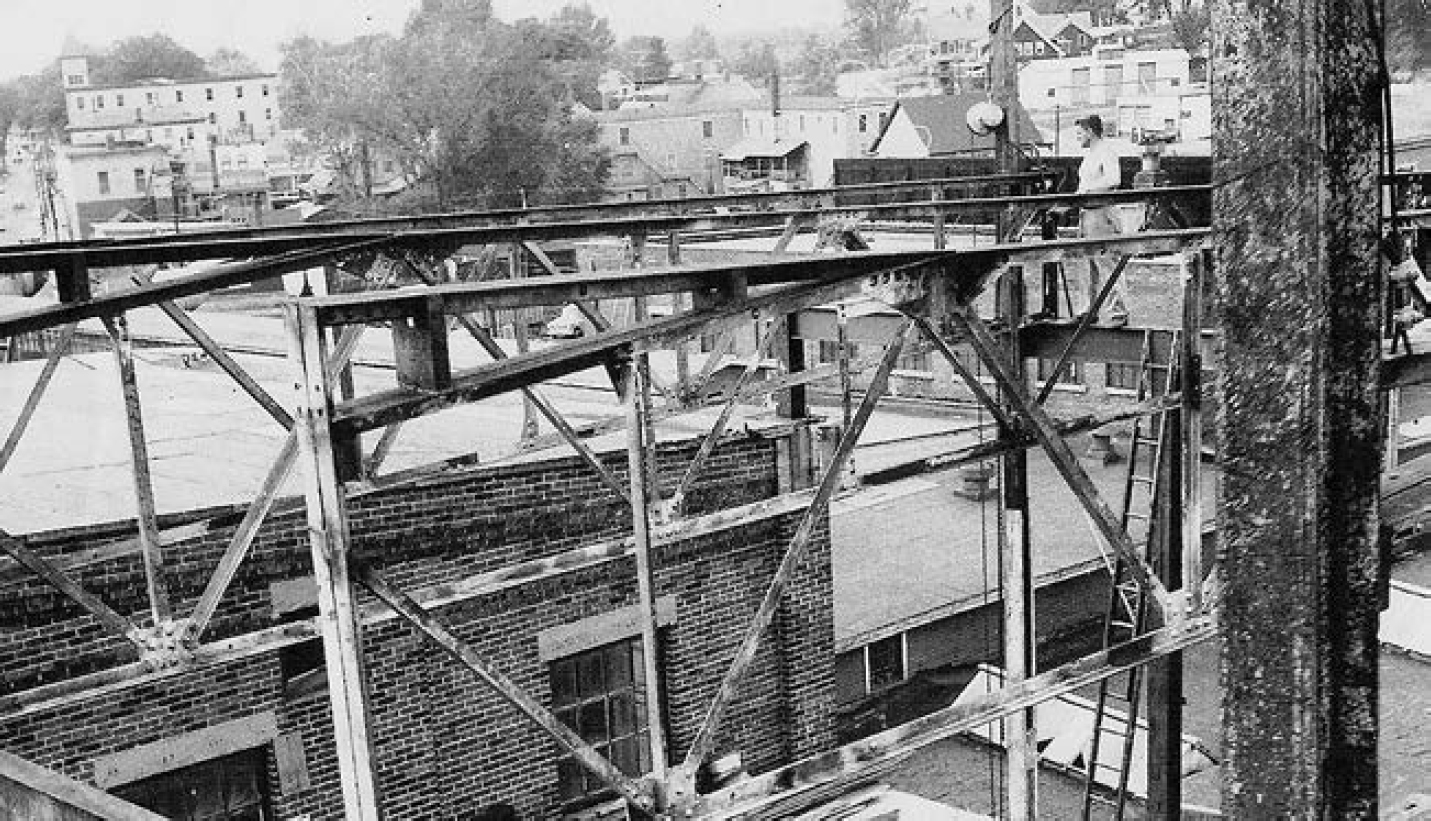

Postwar construction at the mill. (Courtesy GREAT)

“Wemyss don’t want to give nothin’,” Puss Gagnon remembered. “Wemyss would go down to the diner and drink with the boys. They’d get drunker’n hell. He wouldn’t give. Oh, no. He said you was going to get so much. You could go on strike if you want to. It wouldn’t amount to a piss hole in the snow.” Zo Cloutier said: “Back then you had to fight for what you wanted. If you didn’t, you wouldn’t get nothing. They used to go out on a strike for three or four cents. After a Depression, people want a little bit more money. The only way you could get it was to fight for it. The unions, to me, were a great thing. Back then you needed to have people all stick together when you wanted something.”

Once the strike was settled, the transformation of the mill commenced. Fred Shannon’s father was part of the construction crew that was replacing a leaky cement wall by the filter plant. They had installed rebar for the eighteen-inch-thick, new walls, but they had dropped some short wooden sticks among the rebar, and they needed someone small to retrieve them. “Somebody come over and asked me if I thought I could crawl in there, because I was just a little fellow; I probably didn’t weigh only forty pounds,” Shannon recalled. “I was able to crawl right down through all that stuff, and pick out all those sticks. I got paid a whole dollar for that.”

“Everybody knew everybody,” Fred remembered. “Everybody got on good, as far as I can see.” Young Fred and his mates thought the mill was a wonderful playground. On occasion, they commandeered a railroad handcar from behind the mill: “We’d push that all the way up on the main tracks, way up, and then get on, and ride all the way down through behind the mill—have a good ride. Hey, back then, no television. There wasn’t much to do, except find things to do.”

“We did everything we could to make a penny,” he said. “All summer long we’d pick berries and sell them, and we’d go to Emerson’s and buy a couple of boxes of .22 shorts. Then we’d go up to the dump and spend the rest of the day shooting rats. It kept us out of trouble. After a while they wouldn’t let you shoot at the dump anymore. Too close to town. They’d see kids up there throwing a bottle up in the air and then shooting at it with a .22. That could be kind of dangerous, I guess.”

The mill’s river crew was casual about leaving explosives lying around the riverside woodpiles. Fred and his buddies took notice: “By every pulp pile, there was a little shack where they used to have dynamite. Three or four of us got this little half stick of dynamite and a piece of fuse. We went way up Bag Hill somewhere and set it on a rock and stuck a hole into it and put a fuse into it and lit the fuse, and we run like hell. We waited and waited and waited, and nothing happened. We didn’t know you had to have a cap on that fuse. The dynamite was smoldering, but there was nothing to make the dynamite blow. One of them that we was with—I won’t mention his name—picked it up, carried it down, and set it on the road. One of us had a .22. So we was pulling up with that .22 trying to hit it. PEEEEYOUUUU. PEEEEYOUUUU. About the third time, the whole earth shook. The loudest noise you ever heard. Now there was four young guys going down that Bag Hill Road right in a race. I never was so scared in my life. That .22 bullet set that off.”

Jim Wemyss Sr. installed a large new boiler in 1948 and a new General Electric turbine. The old paper machines had been run by steam-driven shafts. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, mill electricians installed electric motors to operate the older paper machines at faster rates. On one occasion, Herb Miles was using uninsulated pliers: “I reached in to get hold of a wire. I had a hold of the conduit. Of course, a conduit is grounded. There I hung. Pulled me right up—pulls your muscles right up. The fellow with me there—I said, ‘Pull the switch!’ That’s all I could say. ‘Pull the switch!’ There’s another fellow stood down there looking up at me. If he’d taken me by the pant leg, he could have pulled me off. He thought he was going to get a shock if he got ahold of me. If I’d had a weak heart, I’d have been dead. Finally I kicked the eight-foot ladder out from under me, thinking I might drop. But the [wire] kept me right up there. Finally the wire broke, and down I went kerploof, right on the cement floor, weaker than a rag. After that we got insulation for the handles of our pliers.”

Number 4 paper machine’s twelve-foot-high Yankee dryer (left and center) and dry end (right) at the time of installation in 1948. Jim Wemyss believed that the man in the straw hat at left was Guy Cushing, a longtime paper machine operator. (Courtesy GREAT)

During the war, Old Jim had ordered new tissue machines from Pusey and Jones for Groveton and the mill in Gouverneur, New York. Pusey and Jones had suspended manufacture of machines in order to construct battleships and aircraft carriers. After the war, the Wemyss family order was at the head of the queue.

The new machine, named Number 4, was installed in 1947–1948. “That was one of the largest tissue machines in the world at that time,” Jim Jr. said. Unlike fine-papers machines, this much shorter, 160-inch-wide machine had a single twelve-foot-diameter “Yankee dryer” instead of a series of presses and dryers. As the tissue came over the Yankee dryer under high pressure, it hit the creping blade, called the “doctor blade,” that peeled the thin tissue off the dryer and fed it onto a reel. Fred Shannon and his chums thought the installation of Number 4 was quite a spectator sport: “They had that great big old monstrous dryer, and they had taken out the brick wall and brought it in on a railroad and then rolled it into the machine room.”

Number 4 paper machine was a twenty-first birthday present for Young Jim, who went to work full time at the mill in 1948: “[Father] said, ‘That’s yours. Now learn how to run it.’ I said, ‘OK.’ I didn’t know anything about it, period, but it was a good learning program.” Decades later Joan Breault observed: “Jim Wemyss Jr. was probably the best man on tissue machines probably you could ever find. He could take a piece of beater pulp and chew it in his mouth and tell you if it had enough of any chemical in it.” When I mentioned Breault’s comment, Wemyss replied: “Paper to me is an observation. It’s just a trick of knowing what you’re doing.”

Jim Wemyss Jr. never attended business school, yet he claimed he earned his MBA at age eighteen: “When you have two very fine businessmen that talk to you ten hours a day from the time you’re fourteen years old, at the breakfast table, at the lunch table, the dinner table, about what happened with this, what happened with that. It’s a case history, basically, an MBA. My grandfather, how did he come out [of the stock market] before the Depression? Why did he know to get out? These things are all I heard all the time. We never talked about any ring-around-the-rosie stuff. It was always business around me, and I had to learn to run everything in the paper mill. Everything.”

“When I first went to work for my father,” Jim Jr. remembered, “I said, ‘What do you want me to do?’ He said, ‘Walk around.’ I said, ‘What’s my job?’ He said, ‘Walking around.’ So I walked around one day, and I came back, and I said, ‘I walked around.’ He said, ‘Go walk around some more.’ I walked around, and I walked around. All of a sudden I was walking by, and one of the paper machines was shut down, and so I said, ‘Why is this paper machine shut down?’ I found out why and what they had to do to make it run again. I learned what was wrong with pumps, or electric drives, or steam engines. I kept walking around. I was in the digester room, and there was a problem. ‘Why are we having a problem?’ It was the greatest education I ever had. ‘Walk around.’ I kept walking around, and pretty soon I got quite knowledgeable.”

Around this time, the Factory Insurance Agency (FIA) announced it was canceling Groveton Papers’ policy. “I walked into [Father’s] office. He said, ‘Well, son, I think you’d better hear this. This is pretty serious.’ The head of FIA for this area was there. [Father] said, ‘They’re canceling our insurance.’ Because the mill was dirty. The war had just ended. It was not being taken care of. It was not what it should have been. I said, ‘You know, sir, I just came back from the war, and I got shot up a little bit. I came back to this family business, and I don’t want you to do that to me. I went to military school for four years, and I was in the army, and they have ways of doing things to make things clean and neat. I want you to give me a break. I’ll take charge of this mill, and I guarantee you, in sixty days you won’t know it.’ He said, ‘Really, soldier? Will you come down to our fire school in Hartford?’ ‘Yes. I’ll be there.’ He said, ‘I’m going to give you six months.’ And he looked at my father, and he said, ‘He’s in charge?’ ‘Yes. He’s in charge.’ And Genghis Khan came to work [laughs].”

After he returned from fire school, Genghis went to work: “We had the women in the finish room shutting off sections and taking the sprinkler heads out. They were all corroded. They were cleaned with wire brushes and washed out, and all the pipes were blown out, and the steam pumps and the high-pressure water pumps in the mill were all taken apart and put back together in perfect shape. Every paper machine once a year had to be cleaned and painted. This place was sparkling. When I got through, the president of FIA said: ‘Any mill you have, Mr. Wemyss, we’ll insure.’ I was fanatic about it. I think the disease caught. Everybody had pride in the mills here and wanted the mill to be clean.” Wemyss’s longtime assistant, Shirley MacDow, called him “a real neatnik.” “Cleanliness in the mill was godly to him,” she added.

“It had to be immaculate,” Wemyss emphasized. “There was no excuse for it not to be immaculate. And if you did, you were talking to me, and you didn’t want to talk to me about that [laughs].” A clean mill was a safer, more profitable mill: “It pays in safety. It pays in maintenance. It pays in everything.”

Most of the mill workers of that era approved of the policy, often contrasting it with the filth they encountered in other mills. “I’ve had all kinds of people come up to this mill,” John Rich said. “‘How the hell do you keep this mill so clean?’ And I say, ‘When you ain’t doing your job, you grab a broom. They’ve got all kinds of brooms setting around. You use it.’ And they did. He was fussy about that, and it was a good thing. You know how it is; dust builds up. You cleaned that finishing room every day, every shift. Three times a day. Blow that out, clean it out.”

Jim Wemyss Jr. starting up Number 4 paper machine in 1948. (Courtesy Jim Wemyss)

Dave Miles remembered the chemicals they used to clean the floor once a week: “They would burn you if they got on, but you had a spotless floor when you got done. It smelled kind of bad, but it did the job. I was sent to a couple of other mills. I thought the Berlin Mill was very dirty as compared to our mill.” Lawrence Benoit also recalled cleaning the floor: “You’d wash the floor with [Oakite]. That stuff was so strong, if you had rubber soles on your shoes, you’d feel it stick to them. When you got done washing that off with a hose, that cement would look just like brand new. It’d eat the stuff right out of the cement. If you left that too long on the side of the paper machine, it would eat the paint right off on the bottom.”

Puss Gagnon was not an admirer of Genghis Khan’s campaign: “[Jim Wemyss was a] miserable son of a bitch. I never liked him; he never liked me. When we were over in the new fire room [c. 1948], he come out one day [and said], ‘You ought to clean up these feeder motors.’ I said, ‘You got a cleaner here to do that stuff.’ He said, ‘It wouldn’t hurt you a bit.’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘probably not. But it wouldn’t be within now or June, it would be just as fuckin’ dirty.’ ‘I’m gonna show you different,’ he says. He gets himself a bucket and some cleaning stuff. He starts cleaning the motors. The cleaner happened to come by. I said, ‘Go up on the top floor and take the air hose and blow the top floor down. The shit started to come. [Wemyss] throwed the fuckin’ bucket. He told [head of the union, Dick] Currier, ‘Come back at three, and I’ll show you these fuckin’ motors are clean.’ When [Currier] come back, he says, ‘I wonder where Jimmy is.’ I said, ‘I don’t think he’ll be back.’ He said, ‘What did you do to him?’ I told him. ‘You dirty son of a bitch,’ he says.”

JAMES C. WEMYSS SR. dominated the Groveton mill throughout the 1940s. “He’s a man that worked twenty-four hours a day,” his son recalled. “That’s an exaggeration. But he was up at five o’clock in the morning. He was there, and he knew everything about everything. Until he got seriously ill, he was purchasing director; he was the sales manager; he was the plant engineer. That’s probably why he broke his health. He had to have absolute control over everything. He lived nicely, but he was not a playboy. He was a fellow that really wanted to be there and see things done. He was respected by the men in the mill; they liked him; they knew what he was capable of doing.”

Young Jim described his father’s early morning routine: “He’d be up at six thirty in the morning, and he’d meet the machine tenders and the back tenders and the pulp mill men walking home and stop and talk to them. By the time he got to his office, he knew what happened all night long. I’d walk in about seven o’clock. ‘Did you know this?’ ‘No, I didn’t. I haven’t had a chance to look around. How’d you know?’ Then he told me. I said, ‘Hey, that’s pretty good. I like that.’”

Young Jim came in late one morning, and his father said: “‘So we’ve got a banker in the family?’ ‘Well, gee, I was up the last five nights in a row here.’ He said, ‘You want to stop that? When they call you in, call everybody else. Call everybody. You’re in there; you don’t want to be alone.’ Pretty soon they stopped calling me.”

John Rich described Jim Sr. as “a temper-y old boy.” Edgar Astle, a machine tender on Number 1 paper machine in the early 1950s, told his son about one of Old Jim’s outbursts: “[He] would walk through the mill every now and again, and boy, people would tremble. I guess they’d run over the chests and the stock had come out on the floor, and he threw a fit. He took a handful of change out of his pocket and threw it into the gutter, and he said, ‘You guys are throwing my money away.’”

Shirley Brown, whose husband had a celebrated run-in with Old Jim in the mid-1950s, thought: “He wanted to take Willie Munroe’s place, because Willie Munroe—his famous saying was, ‘I own this town and everybody in it.’ When Old Jim, as we used to call him, came, I think he wasn’t as fair as Willie Munroe was, because whatever Willie Munroe said, people knew that was a fact. But with Jim, it depended on whether he was sober or not [laughs]. I’m sure you’ve heard some of these stories.”

After decades of hard work and hard drinking, Jim Wemyss Sr. nearly killed himself. The Democrat reported on August 17, 1949, that he was seriously ill in the Weeks Memorial Hospital in Lancaster. Jim Jr. vividly recalled his father’s brush with death: “My father became gravely ill. Had two-thirds of his stomach removed with ulcers. My father was bleeding internally, and he passed out. I drove my father to the hospital, and [Dr. Merriam] put a needle in my arm [to draw blood for a transfusion], and we lay down on the street, right in front of the hospital. He stabilized him. He came out of shock. I sent a message to the mill; we all had dog tags from the war with your blood type on them. Mine was O, so I said, ‘Any man with O that wants to come down and help my father out, just walk off your job and get down here as quick as you can.’ They liked him; there was fifty people down here in twenty minutes.”

Young Jim was not yet twenty-four years old: “When [Father] was back, rational in the hospital, his brother-in-law walked in, Dr. Hyatt. My father looked at him and said, ‘I had a serious operation, didn’t I?’ He said, ‘Yes, Jim, a very serious operation.’ He said, ‘I suppose I won’t to be able to eat properly or do anything the rest of my life.’ [Dr. Hyatt] said, ‘No, no. Within reason, you can do that.’ And then he said, ‘But there’s one thing you can’t do. You have to walk away for one year. And never look back. Hire a professional manager to run your companies. Get a manager and go someplace. Or you’ll be dead within a year.’ Just like that. So [Father] said, ‘I’ve taken care of that matter already. I’ve hired the man.’ I happened to be in the hospital room, and I said, ‘Who’s the new manager?’ ‘You.’ I was in charge, but nobody knew it. My signature and his, you could not tell the difference, except I would drop off the ‘Jr.’ Every time somebody came to me and said, ‘What do you think about this?’ I said, ‘My father’s not feeling well, and he’s up at the company house. I’ll go up and ask him.’ He wasn’t there, but I’d go up and then come back and say, ‘Do this.’ Who would question me? So that’s how I fell into it, so to speak. I owe that to my grandfather and my father. It really wasn’t that difficult for me. My father basically left me alone from then on.”