THE OVERTHROW of the shah of Iran in January 1979 triggered another sharp rise in oil prices, the hostage taking of fifty United States Embassy officials in Iran in November 1979, and a war between the new Iranian government and Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime in 1980. Uncertain oil supplies were an even more serious threat to the mill than price rises. Wemyss and his managers were losing control over the mill’s destiny.

Saddled with a $25 million a year energy bill, Wemyss decided to convert Number 1 boiler to burn hardwood chips. In August 1981, mill general manager Jack Hiltz optimistically wrote: “The conversion of No. 1 boiler to wood chip burning seems to be coming along quite well, and we expect to be starting the converted boiler in October. We certainly will need it before the snow flies.”1

The wood-fired boiler missed the intended November 1, 1981, start-up date by two months. It used oil for several weeks while the system was “de-bugged.” Early in 1982, during a bitterly cold stretch, the mill started burning wood chips, and quickly discovered all sorts of problems. The belts alternately froze or slipped. The hopper over the boiler plugged up with chips. Although the boiler worked well when fed wood chips, design flaws with the tubing prevented running the boiler at more than half capacity.2

Unknown to the Groveton mill community, Diamond was fighting for its life, and Wemyss was under tremendous pressure from the Diamond board. Greg Cloutier, son of two mill workers and nephew to a dozen or so others, was an engineer who had recently directed the installation of the first large industrial wood-fired boiler at Georgia Pacific’s Gilman, Vermont, mill. One day Jim Wemyss Jr. paid him a visit. Cloutier remembered: “[Wemyss] basically says, ‘Hey, we’re trying to build a wood-fired boiler in Groveton, and it’s killing us. It’s not running.’”

Not long thereafter, Wemyss flew Cloutier down to a Diamond board meeting: “Mr. Wemyss says, ‘This guy doesn’t work for us. He’s got no skin in the game. I want you to hear him out. He’s making it work.’ At the time I was doing a lot of ice climbing. I just got done with a predicting avalanche class, certifying to do some guiding. Jimmy’s kind of rubbing [the Diamond engineer’s] nose in it a little bit. I come in, and the crescendo of the meeting is this guy says, ‘Tell me this, if you’re so smart, how do ice crystals plug up those feed conveyors and it doesn’t flow? Why shouldn’t it just slip?’ I said, ‘Clearly, you don’t know or understand the metamorphosis of a snowflake.’ The guy was completely taken aback. I could list at that point the four dynamic phases of ice crystal formation changing to a grain. And I then said, ‘That’s why you don’t have wood falling into the boiler.’ The guy was completely dumbfounded, and Mr. Wemyss said, ‘See, he knows what he’s talking about.’ Then I left the room. [Soon Wemyss] came out, and he said, ‘Oh! That was so good! That story you made up on the metamorphosis of a snowflake was terrific! We’ve got the money to make the modification.’ I don’t know if it was then or on the way back home, he made me an offer to come work for Groveton for substantially more money than I was making at Gilman. I think the fact that I volunteered to do something for Groveton without pay was important to him. He was always convinced that [my] family was all bullshitters. This confirmed a theory he already had.”

After Cloutier had had an opportunity to study the Groveton boiler conversion project, he told Wemyss it would be necessary to make substantial changes in the design of the fuel delivery system and the method of removing the wood ash. Three million dollars later, the wood-fired boiler started up in November 1982, a year behind schedule. The boiler produced two hundred thousand pounds of steam an hour and was expected to supplant 85 to 90 percent of the mill’s fuel oil requirements. The mill saved money and was buffered from OPEC oil price swings and embargoes. The boiler consumed about fifty tons of chips—roughly two and a half tractor-trailer loads—an hour.3 A huge pile of chips appeared in the wood yard where the pulpwood piles had been prior to the closing of the pulp mill in 1972.

“A wood-fired boiler was tough for the men who ran it,” Cloutier acknowledged. “It really meant that they had to work. Making good paper on the paper machine was an art; firing wood was, in my mind, the same thing. You get a feeling about the system you are running. If [the crews] weren’t paying attention, it was tough.”

Cecil Tisdale, a boiler room supervisor, thought it was the “worst thing they ever did.” “We had more trouble with that, more maintenance,” he grumbled. “Wood causes problems. As far as I’m concerned, the equipment they put in just didn’t work good. They never could get the steam pressure they wanted because the boiler would smoke all the time. Call-ins in the middle of the night. Conveyor’s gone. Motor’s burned up. They used to have a conveyor to take all the ash out. That blew up twice. Once I was headed in there to find out what the trouble was. I opened the ash house door, and it blew right then. Whoa, I got back outside pretty fast.” Eventually the ash house burned down.

While the mill was grappling with the fallout from the oil crisis, Anglo-French financier Sir James Goldsmith had embarked on a campaign to take over and dismantle Diamond International. Late in April 1980 Goldsmith offered to buy shares of Diamond International for a “premium.” When Diamond’s stock jumped $3.25 on April 28, the Wall Street Journal took note. Rumors of an impending sale swirled. On April 30, the Coos County Democrat headline asked: “Diamond’s stock sold?” The brief page-one article noted that Diamond’s corporate headquarters had no comment, and Jim Wemyss was out of town.4

Few in Groveton realized that Diamond was fighting a losing battle for survival, but they could feel the gloom descending upon the mill. To boost morale, mill managers launched an in-house newsletter, the Papermaker. Jack Hiltz, production manager, wrote in the December 1980 inaugural issue: “One of the reasons for having a newspaper is to keep people informed about events that affect their lives and the society in which they live.”5 An unspoken additional reason was to allay fears stoked by the local rumor mill.

The Papermaker published four to six times a year until 1992. It reported on promotions, retirements, safety issues, new mill projects, the mill’s bottom line, and birthdays. It also included cheerful prattle and quirky photos of employees in Halloween costumes as it tried to put the best face on an increasingly hostile economic environment. Vice president and general manager L. J. Alyward wrote in that first issue: “Our company has been very fortunate in obtaining enough business to operate fully (with one exception) during the past year.”

To improve its competitiveness, in 1980 the mill began to experiment with making alkaline paper. The traditional acid paper was made by adding common alum to the pulp. Alum allowed papermakers to add rosin to the mix; rosin improved paper’s ability to absorb ink without blotting. Papermakers also added white clay to the stock to fill pores and make fine papers smoother. Since clay is cheaper than wood pulp, the more clay fill used, the lower the production costs.

When chemists developed a substitute for rosin, it became possible to replace the acidic alum with an alkaline system that used calcium carbonate, or lime, instead of clay as filler. Alkaline paper is stronger than acid paper; it lasts far longer, and it does not turn yellow and brittle. It is cheaper to produce because a higher percentage of lime filler and a correspondingly lesser amount of pulp can be used in the process.

Early in 1981, the mill made a trial run of the alkaline process on Number 1 paper machine, using high-quality, finely ground calcium carbonate from Vermont’s marble quarries. A writer in the Papermaker hailed the trial run as an “outstanding success.” A subsequent alkaline trial was a disaster. “We had a young man here who wanted to change to alkaline paper, which is more or less the standard of the industry today,” Jim Wemyss explained. “I said, ‘That’s a good idea. Let’s see how it works. Take the smallest paper machine and make a small run, package, and distribute it, and let’s find out what the reaction is.’ What did he do? He put the whole mill on alkaline. We ended up with a million dollars worth of paper that we had to burn or bury, and almost lost one of our biggest customers [Gestetner] because of his arrogance in doing such a thing. He left the mill, and I happened to come back into the mill. The people said to me, ‘What are we going to do? This is god-awful. We can’t run the paper machines.’ The whole place was chaos. We were hauling it to the dump. All the [fine-papers] machines were terrible. I said, ‘There’s only one thing to do. Dump all the chests, and we’re going to put it back on acid in the next—[raises voice] immediately! [Pounds desk] Right now!’” Wemyss fired the manager. “If he’d been there, I would have been upset with him, but I would not probably have been as severe in my judgment. But when he put the whole mill on [alkaline], and then left and was a thousand miles away, playing golf, and his troops were in chaos—that’s not excusable to me. I said, ‘You no longer work for us.’” Rule number one for Jim Wemyss: An officer never abandons his troops when they are under fire.

“Gestetner could not use that paper. Every office all over the United States that had their machine—all of a sudden, it wouldn’t work,” Wemyss continued. “Normally, that’s an unforgivable sin, and the people throw you out. Because of my friendship with the chairman and president of the company, we were able to pull it out of the fire.”

It would be nearly a decade before the mill successfully converted to alkaline paper using a synthetic calcium carbonate. The ground calcium carbonate used in the early trials was so abrasive that it destroyed pumps and wires on papermakers. A $15,000 wire that should last a month or two was destroyed in a few days.

Susan Breault concluded an upbeat report in Papermaker on two trial alkaline runs in early 1982 with this jarring exhortation: “Success in the [alkaline conversion] process can only be accomplished if everyone works as a team. This is a strong healthy town and with everyone’s help we can make it grow in wealth, health, and bring back the spirit and moral[e] which once lived here in these walls.”6

Mill morale had taken a huge hit in the fall of 1981. Negotiations for a new union contract broke down. On September 12, 1981, Local 61 struck the mill over wages, the pension plan, and proposed changes in seniority rules. Years later, Jim Wemyss still angrily referred to the union president as an “idiot.”

The Democrat editorialized: “The strike comes at a bad time. The paper workers can not stand getting along on $45 a week for very long, and if reports of the mill’s financial status are accurate, neither can the mill stand to lose those daily shipment revenues for very long.”7 “I can remember not eating that well,” back tender Dave Miles said, “or paying the bills.”

The strike grew ugly. The mill reported it had found ten sticks of dynamite in the boiler room. When an injunction prevented the union from picketing the Campbell plant in North Stratford, someone slashed truck tires, and the radiators of three Mack trucks in a locked garage were smashed in by crowbars. Two men in North Stratford were arrested for trespass and criminal mischief. A salaried employee’s wife reportedly received a threat over the phone that her house would be torched.8

Shirley MacDow, a vice president of Diamond, had a nightmarish time: “They came down and ruined our garden. Threw tomatoes all over my house. Our little girl was only a few years old then. So, Mr. Wemyss instructed, probably Joe Lacroix and a couple of others, to keep an eye on me. Maybe they’d set the house on fire. We didn’t know. The mind-set changed from, ‘Hi, how are you, Shirley?’ to ‘You’re our worst enemy.’”

Roger Caron reluctantly joined the picket line: “I remember part of getting your strike benefit was walking a picket line. I really didn’t like that. People would drive by and look at you. Even Wemyss came along, and I’d known him all my life. He lived right behind my folks’ house. It just felt like an adversarial position to be in.”

Pam Styles, a nonunion office worker, had to cross the picket line. “I didn’t have a problem with the people maybe because I was friendly with a lot of them,” she remembered. “One of my friends had a guy spit on her. It’s a small community, and people know everybody, and it’s just I’d never do that. I know I’m upset if somebody is doing my job, [but] we need the work too.”

Styles was assigned to work in the fine-papers finishing room to run off reels of paper that had been produced prior to the shutdown. “I worked on the Wills machine,” she recalled with amusement. “That was the machine that cut the paper to eight-and-a-half by eleven, or eight-and-a-half by fourteen. It was fun because for a while we didn’t know what we were doing. It was something different, out of the ordinary. I’d get right up on the machine when we got a jam and pull the paper out. It kinda gave us firsthand knowledge of what they were doing.”

During the monthlong strike, rumors swirled: Boise Cascade was going to buy the mill; a paper machine was going to be moved to Old Town. When the strike ended on October 11, the new agreement gave the seven hundred union workers a 9 percent pay increase in the first year and an 8.5 percent increase in year two.9 No paper machine was shipped to Old Town, but old Number 1 paper machine never restarted, and a couple of weeks after the strike ended, it was scrapped. Murray Rogers said: “It was kind of a retaliation move because of the strike.” As many as eighty jobs disappeared with Number 1.

A month after the strike ended, the Democrat ran a short page-one article headlined: “Diamond Intl. Could Be Sold.”10 Readers of the paper learned that over the previous three and a half years, Sir James Goldsmith had bought up 40 percent of Diamond’s stock.

Goldsmith and his merchant banker collaborator, Ronald Franklin, had made a stunning discovery: timberland-owning corporations, such as Diamond, listed the value of their forest holdings at a fraction of their potential market value. If the hostile takeover bid succeeded, Goldsmith could sell off Diamond’s pieces, including the Groveton and Old Town mills, Diamond’s playing-card business, Manchester Machine, and other non-timberland assets to pay off the huge, high-interest debt, while retaining the timberlands, valued by Goldsmith at $723 million, as profit. Franklin later explained the rationale: “Diamond interested us because of our philosophy which pervaded everything we did in America: that the sum of the parts of most conglomerates was worth a great deal more than the whole.”11 Diamond’s undervalued timberlands made the corporation irresistible to a corporate raider.

“[Diamond] was a fantastic company until Jimmy Goldsmith came along,” Jim Wemyss told me. “You know what was wrong with Diamond? We were too rich. We had no debt. We had four million acres of land on our books for twenty-five dollars an acre. We were a very, very successful company. Any company like that was a target for these people. You couldn’t stop them.” Diamond owned eight hundred thousand acres in northern Maine, ninety thousand acres across northern New Hampshire and northeastern Vermont, and another ninety-six thousand acres in the Adirondacks. I asked Wemyss why Diamond had valued its timberland at one-fifth or one-tenth its market value. “The trees are growing every day, and so their value is increasing every day,” he explained. “You don’t have to report it as income on your company and pay taxes on it.” Wemyss acknowledged that the low valuation translated into a lower capital gains tax rate paid by the seller if and when the land was sold.

Jim Wemyss led the fight against Goldsmith on the Diamond Board of Directors. “I kind of remember sitting in his office and listening to him vent—frustrated vent,” Greg Cloutier said. “Mr. Wemyss really saw this [takeover] as potentially the end to Groveton and the way Groveton worked and the way all of the different entities worked together to make the Groveton facilities profitable.”

In the fall of 1981, two major Diamond shareholders, Conley Brooks and Old Jim Wemyss, sold their shares to Goldsmith for forty-two dollars a share, thirteen dollars above the price fetched on Wall Street. Jim Wemyss Jr. did not agree with his father’s decision, but he did not blame him either: “My father wasn’t happy with Diamond about that time. In any mergers like this, when your stock is selling for twenty-eight and somebody offers you forty dollars for it, and you’ve got many thousands of shares, it’s a lot of money. Father, in his inner thinking, said, ‘That damn son of mine, I know him, he’s going to screw this deal up. I’m getting up there, and I want to get my estate in order. This might be a good window for me to do this.’ Goldsmith called him up, and [Father] said, ‘I’ve got so many thousand shares; I want you to nail it for me right now: forty dollars, forty-two dollars.’ Maybe he asked a little bit more. Goldsmith saw the chance to grab that big hunk of shares, and they made a deal. The next thing I knew, [Diamond president Bill] Koslo said, ‘Your father just sunk us.’ I said, ‘I had nothing to do with it, Bill.’” Early in November 1981, as Koslo agreed to discuss terms of the takeover with Goldsmith, the New York Stock Exchange suspended trading in Diamond shares.

Over the next year, as the final stages of this boardroom drama played out far from Groveton, most mill workers heard rumors but were in no position to take any action. “The guys on the machine knew there was something going on, and you’d hear rumors here and there, but no, we did our job, and waited to see what was going to happen, just do your job and that was it,” Ted Caouette recalled. Finally, on November 1, 1982, Bill Koslo recommended that Diamond shareholders accept Goldsmith’s offer, and 89.6 percent of Diamond’s shares voted in favor of the sale.

To pay down his $660 million debt, Goldsmith moved quickly to sell off all Diamond’s assets except the timberlands. James River Corporation of Richmond, Virginia, had bought the Brown Company paper mills in Berlin and Gorham, New Hampshire, late in 1980. In May 1983, James River (JR) agreed to pay Goldsmith $171 million for Diamond’s paper division, which included the Groveton Papers mill, Campbell Stationery in North Stratford, and Old Town’s pulp and paper mills. JR paid $75 million in cash, common stock in JR worth $19.8 million, and preferred stock with a value of $76 million.12 Goldsmith paid Jim Wemyss $150,000 a year to remain on his Diamond board. However, when Sir James asked Wemyss to help dismantle Crown Zellerbach, following another successful hostile takeover of a paper company in 1985–1986, Wemyss refused.

Jim Wemyss tried to persuade his fellow board members to consider the rights of other stakeholders, but to no avail: “I couldn’t get rid of Jimmy Goldsmith. I tried, but nobody would support me. I knew what he was trying to do. The board’s position was: Let the stockholders vote. If you don’t allow that to happen, you’re depriving the stockholders. They just, ‘I’ll take the money,’ and the people that are working there—‘The hell with them. They lose their job, but I’ve got my money.’ And I don’t like that.” Thirty years later, Wemyss was still enraged by mention of Goldsmith’s name. “Goldsmith didn’t even know where Groveton was. Never did know to the day he died.”

The arrival of James River in Groveton in July 1983 ended forty-three years of Wemyss family ownership and management of the Groveton Papers mill. Jim Wemyss Jr. would remain a presence in the mill complex for another fifteen years as president and chairman of the board of Groveton Paper Board. Diamond had assumed the Wemyss family’s 50 percent ownership of Paper Board in 1968; James River declined to buy Diamond’s share, and for the next two decades, two independent corporations shared the Groveton mill complex. Almost immediately, the relationship between Young Jim and James River turned hostile.

The bad blood between Wemyss and JR was common knowledge throughout the mill. While Wemyss railed at his successors, Bill Astle suspected James River “took it more with amusement than feeling that they were really getting beat upon, or that they needed to teach him a lesson.” Louise Caouette had known Wemyss when she was growing up. She thought JR might have “exposed him as being a human being.” “Groveton had really put Wemyss on a pedestal,” she explained. “I think James River was pretty free at making sure people knew that Mr. Wemyss was no longer calling the shots; that they were dealing with a corporation, and it wasn’t Mr. Wemyss. I would think that that would have been hurtful to him.”

Wemyss had modernized the mill. He knew its remotest corners intimately. He cared passionately about the mill, the workers, the community, and his legacy. And he had no experience taking orders, or watching other people give orders he could not countermand. “They didn’t like me,” Wemyss said of the James River managers. “I tried to be good to them because I wanted to keep the people working.” What did JR do that was wrong? “They didn’t listen to me; it’s as simple as that. We knew the business; they had a new theory of running the business. They’d have paper machines down in Groveton, and Conway Process meetings up at the Legion with all the millwrights. I said, ‘The paper machines are down.’ ‘We’re having meetings. That’s more important.’”

Greg Cloutier observed: “The James River group really spent a lot of time polishing teamwork and problem solving, communication. That was perhaps a [strength] Mr. Wemyss didn’t have. He was the single focus for everything. Everybody worked together almost because they hated him, or because they feared him. But they worked together. You could take extremely capable men who had terrible people skills, but had extremely good skills at making paper, and they would work under Mr. Wemyss because in many ways, he could control that sort of guy. He could take a high-energy individual that was a pain in the butt to work with and make that guy work well for him. He had that strong leadership, commanding leadership—I mean, he was the alpha dog. There was no question about it.”

Cloutier offered an example of the contrasting management philosophies: “When Mr. Wemyss was there, if you were a key department head and the power blinked so the lights go out, you saw men run from wherever they were. The meeting stopped that second. You ran to your department to get it back on line. [Under] James River, your men were supposed to solve that problem. If you’d done your job right, they had the ability and the skill to make those decisions. They didn’t need you, and you stayed in the meeting. I don’t think that set quite the example.”

Jim Wemyss’s management philosophy was Keep the mill running. He expected bosses to be there when there was trouble and to remain until the problem was fixed. “Don’t tell me you can’t fix it; fix it!” he would holler. When the machines were down, Cloutier explained, “[Mr. Wemyss would] walk through; he didn’t keep on walking. He took his coat off. He stayed. Maybe he was mad to stay, but he stayed. ‘What can I do?’ ‘Rethink what you’re doing here.’”

Chan Tilton, a retired paper machine tour boss, admired Wemyss’s commitment: “If that tissue machine was in trouble, he’d be there. He was a papermaker. He’d come and talk to you. You couldn’t buffalo him. He was an intelligent guy, a little autocratic, but fair. If you needed to replace equipment, you’d get it. [While he ran the mill] there was nobody out of work in the town.”

The key to success for a small, family-owned mill, Wemyss believed, was to offer a diverse product line; don’t rely on one large customer; always upgrade to remain competitive; encourage innovation; waste nothing; operate a clean, safe mill; and maintain a huge inventory of spare parts so that the mill never shuts down for want of a pump or a bearing or a bolt. When orders were down, he directed the crews to run the paper machines at a slower pace, rather than shut them down and lay off scores of workers. Employees kept drawing a paycheck, and the mill was spared the headache of restarting a paper machine.

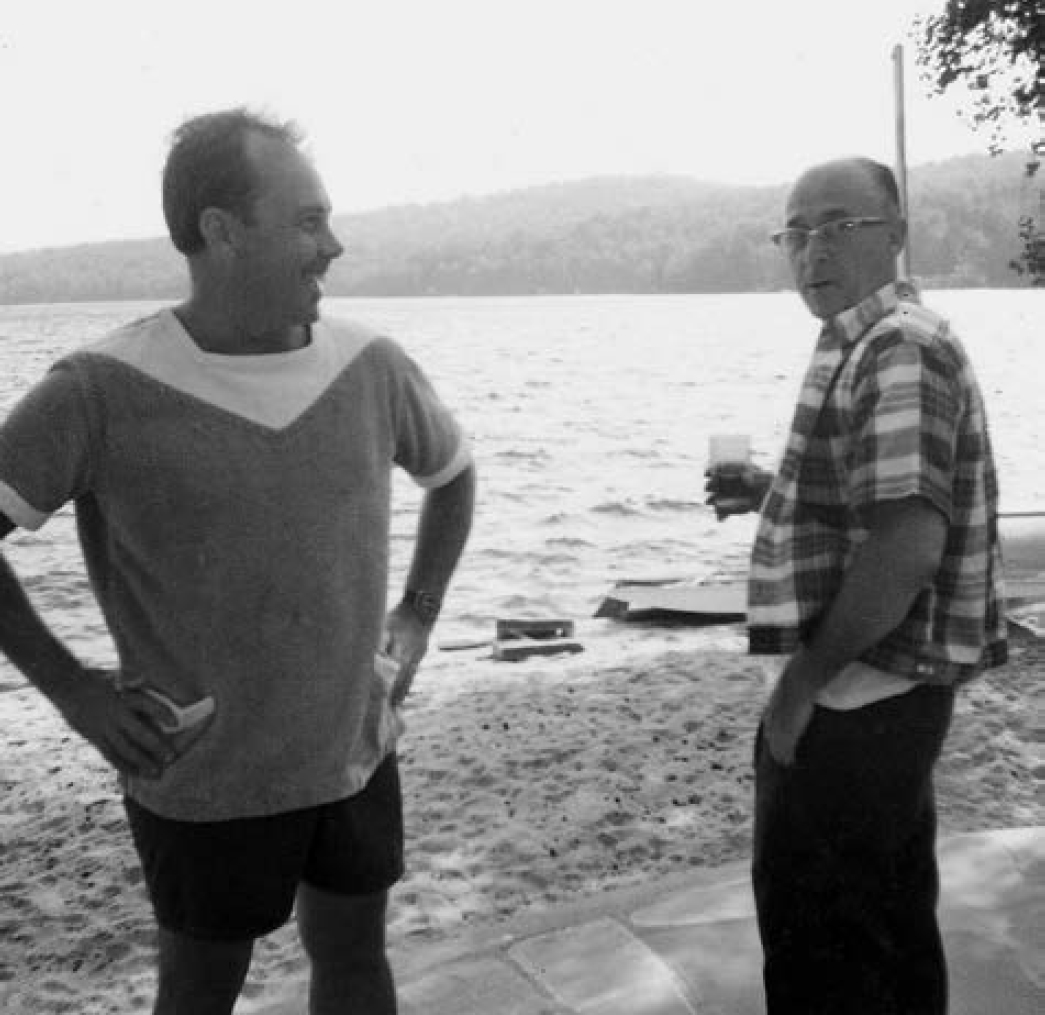

Jim Wemyss with “Jazzo” Kingston, one of Greg Cloutier’s many uncles, at Maidstone Lake around 1966. (Courtesy Greg Cloutier)

“I don’t think Jimmy missed much,” Iris Baird suggested. “I think he conveniently didn’t notice on occasion. But if you had tried to take advantage, he would have known.” Wemyss agreed with her assessment: “I was involved in everything. Little went on that I didn’t have some knowledge of it beforehand.” He was proud that he and his father were hands-on owners: “My father would be working on a paper machine when things were bad, maybe pulling broke off the top press, and I did the same. We were not the managers that lived in New York City and came up once a year and walked through in our tuxedos to see how the paper mill was running. The president was here at two o’clock in the morning or four o’clock in the morning. That’s the way we were.” “We had a very strong work ethic in our family,” he explained on another occasion. “We didn’t talk about what time we went to work or how many hours we worked. If it wasn’t [running well] you were not supposed to be anyplace but where it was.”

He was a local owner, who viewed the mill workforce as a large family: “It was a family atmosphere. I always left my door open. Anybody could walk in. ‘Hi, what’s going on? What can I do for you?’ [Groveton] was my home. Always has been my home.” There was no doubt, however, that Jim Wemyss Jr. was the patriarch of that family. “He could be a dictator,” Greg Cloutier said. Others used terms such as “autocrat,” “old school,” and “son of a bitch.”

Dave Atkinson’s grandfather, “Bucko,” a stock prep supervisor under Wemyss, had a reputation for screaming and hollering. “You didn’t want to screw up for Bucko,” his grandson said. “I think he went to the school where it was ‘My way or the highway.’ Call it the Jimmy Wemyss School of Management. You just scream and holler. I don’t want to say disrespect people, but that was the style back then, and [Bucko] certainly fit the style, which is probably why he was promoted to a boss.”

Wemyss was legendary for his outbursts when a paper machine wasn’t making good paper. He invariably directed his fury at management because the managers were in charge, and Wemyss, the ex-soldier, believed in the chain of command. “I had seen him when he trimmed up some of the bosses,” Bruce Blodgett said. “Kicked that sport jacket of his right up and down the floor and scream at those guys and rip ’em apart. He was not bashful at all.”

Lolly LaPointe, superintendent of the stock prep department, witnessed a few Wemyss eruptions: “I’d come in there eleven to seven. If [the tissue machine] had been haying all night, he’d take off his jacket and throw it on the floor and jump and rave and rant and raise all kinds of hell, and then he’d walk out of the place. Maybe he was hot. But he’d come in there like on a night shift, and would he ever go into a tantrum, mister.”

As always, Wemyss had an explanation: “If you walked into a machine room when you’ve got a big coat from outside, and it’s ninety degrees in the machine room, and it was forty below outside, [and] you’re going to be there for two or three hours, what do you do? Get the goddamn coat off and go to work. It worked. I didn’t go home until it was running. If it was two days later, I was still there. There’s no excuse. It’s got to go. It has to run. And I want it running at 95 percent efficiency if it can get up there.”

For all the screaming, Wemyss rarely fired people. “You didn’t fire people to fire people,” he explained. “You knew their families and their kids. You can’t do that.” Herb Miles maintained that Wemyss rehired most of the hourly workers he fired: “He’d fire more bosses. Jim Wemyss told me himself: ‘I can get those fellows a dime a dozen.’” Bill Baird said: “He had a temper. If you crossed [him], he was just as apt to fire you, as not. But he expected you in the next morning to go to work at seven.” Iris Baird added: “The first time he fired you, somebody said, ‘Don’t pay any attention. He’ll have forgotten by morning.’”

John Rich recalled a man who was fired for oversleeping: “He was on call. They’d call him. ‘Yup, be right in. Be right in.’ He never show up. Jimmy got sick of it. He had him canned, and a year later he hired him back, and he give him a garbage can and one of them big old alarm clocks with the bells on top. ‘You put that goddamned clock in that garbage can, and you set it. That ought to wake your ass up and get you out of bed in the morning.’ I think Jimmy was fair.”

Union contracts forbid the mill from firing an hourly worker without going through the union grievance process. Office workers did not enjoy those union protections. “I didn’t really know him well,” said Pam Styles, who was hired in 1970. “When he was there, I was really, really young. Shirley MacDow was the office manager, so we had dealings with her. Everyone kind of tiptoed around him. I know she bent over backwards to do what [she] could to help him.”

“I don’t think I walked on eggshells, but I kind of understood where he was coming from,” MacDow told me. “I wouldn’t challenge him in any way. People would feel like they were walking on eggshells because if he made a decision, or if he walked through the mill and saw something he didn’t like, the shit would hit the fan.” Characteristically, Wemyss embraced the eggshells image: “If they had something they weren’t doing right, they had good reason to walk on eggshells.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, Greg Cloutier and Jim Wemyss were notorious for their shouting matches. But Cloutier remained because he admired the older man’s commitment to the mill: “You’ll find a lot of business people are very strong and powerful people, and the underlings won’t stand up and protect them from themselves. Mr. Wemyss would say [something like], ‘I expect you to protect me from myself. You’ve got to do what I ask you, but if it’s wrong, don’t do it. Tell me what’s wrong with it.’ He always wanted respect and loyalty. If you did that, you were 80 percent there.” Cloutier pointed out that Wemyss liked foremen who argued with him, adding that they remained union members who were protected by union grievance rules, whereas once they were promoted to supervisor, they became management and no longer enjoyed those protections.

Mickey King’s father was promoted to tour boss, but despite the welcome pay raise, he soon quit because he refused to scream and holler at his former crewmates. He told his son: “I will not blame my help for things that they did not do. I can’t do this.” Mickey described Wemyss as a kind of tragic figure: “Jim is a strange fellow. Just a difficult, difficult person. He surrounded himself with lackeys. He always had people who, ‘What can I do? What can I do? Do you want a drink? Do you want a drink?’ He loved it, and he would belittle them. They were people who were bosses in the mill. People who contracted with him for certain things. He couldn’t help himself; he loved belittling people. You’d see a moment of kindness once in a while from him, and you’d say, ‘Wow, that’s different.’ Then he’d go right back to his—. It’s always been sad, but that was Jim. If you really stood up to him, he would kind of respect that. If you didn’t, he’d insult you right in front of your face. His father was the same.”

Bill Astle described a complicated man who often succumbed to the temptations of power: “He was always considered very authoritarian and perhaps more involved in some people’s lives than they deserved to have him. My perception is he always looked out for what he believed was the best interest of the town. There were times when Jimmy could be a cruel man. He could belittle people. There were people that were hired and fired five times as a boss because he’d fire them and chew them out and humiliate them publicly in front of all of the people that were working for them, and then Jimmy seemed to get a little bit of levity about that, and then he’d come back the next day and say he hadn’t meant that. I think a lot of that was to demonstrate the dynamic of power that he had. One of his expressions was, ‘Employees are just like a can of coke. Go over to the machine, you put your money in, you press a button, and another one comes out.’ I think he was a fairly complex man. He absolutely wasn’t all bad, but ownership meant he could do anything he wanted when he was in his heyday. There really was no check. I suspect he learned many of those attributes from his father.”

Because of his dominant role in the town over the course of half a century, even his admirers vented from time to time. “We used to bitch about him, but he kept us working,” electrician Len Fournier observed. Francis Roby declared in his characteristically terse way: “Jimmy, he was just the boss. I worked for him. He made the paycheck out. That’s all.”

Wemyss promoted locals to management positions whenever he could: “Half our management came out of the union. I can’t think of all the names of all the men that came in here as young boys out of high school and [became] head of the electrical department or head of the labs or running the paper machines and the pulp mills. When they got up in the thirties and forties, and they had a heckuva lot of knowledge, I’d say, ‘Want to try it?’ ‘Mr. Wemyss, I don’t have a college education.’ ‘You’ve got a college education; you’ve got one here.’ It’s always better to bring them up through the ranks. The quickest way to destroy the morale is to say, ‘Gee, I’ve been here twenty years, and I always wanted to be the head of this department, and look at that, he brought somebody in.’ You give him a chance first. You say, ‘You want to try it? You think you can do it?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Go. You got it.’ It has a great morale boost to the people.”

This policy contributed to a much more flexible relationship between union and management. Wemyss recalled a visit to the mill by Leonard Pierce, president of Berlin’s paper mill, who wished to observe Groveton’s high-speed toilet paper winder. Wemyss introduced him to Jim Doolin, superintendent of the finishing room. While they were talking, as Wemyss recounted, “All of a sudden, Mr. Doolin said, ‘Excuse me, sir, I’ll be right with you.’ He turned away, yanked the adjustable wrench out of his pocket, loosened one of the folding plates on the seventeen-inch napkin machine, and moved the plate a little bit, which you do every so often. Leonard said to me, ‘What did he just do?’ ‘I think he adjusted that folding plate on that napkin machine.’ ‘What did you say his job was here?’ ‘He’s superintendent.’ ‘We can’t do that in Berlin. [The union would] shut the whole place down.’ I said, ‘They won’t shut it down here. I would adjust it if I felt like it.’”

During a public interview, Wemyss suggested another reason for promoting locals: “The best possible thing you could do was get a good man out of the union and put him in charge of the department. And shortly thereafter he says, [in an exaggerated voice] ‘Those goddamned union bastards . . .’” The audience of former mill workers roared with laughter, but it was a great insight. Lolly LaPointe was promoted to day supervisor in stock preparation after nearly twenty years as a union member: “In my heart, I was a union man, I guess. Personnel problems really got to me. Towards the end of it, all these young kids they were hiring, I don’t think that any of them had ever worked a day in their lives. They were great kids until they got in the union. You’d ask them to do something: ‘That ain’t my job.’ I guess I was from a different generation. You was lucky to have a job.”

Despite the bullying and tantrums, Wemyss really cared about his adopted community. Shortly after his election to selectman, he learned the town swimming pool was too run-down to use: “One day I saw a little kid walking out toward my home. He had a tube over his shoulder, and I said, ‘Where are you going?’ ‘I’m going to go swimming in the river.’ I said, ‘No, you’re not. You’re too little to do that. Why don’t you go in the swimming pool?’ ‘The swimming pool’s broke.’ I went down to the mill and said, ‘Nobody goes to bed until the swimming pool in Groveton is fixed. Put new toilets in, put new stainless steel valves, pumps, fill it up with water, chlorinate it. Nobody goes to bed. These are your kids that swim there, and I don’t want one to drown. Do it!’ And they did. I think we spent between $25,000 and $30,000 before we got through, getting that thing right. It never should have gotten down like that.”

As a boy, Dave Atkinson witnessed Jim Wemyss’s tough love: “My dad worked for Paper Board in the office. I think he was very good at what he did. But he had, at times, a pretty serious drinking problem. It got to the point where it was affecting his work. I can remember Jimmy coming to our house and saying, ‘Anne, we’re going to get this guy some help. Thomas, you’re going to Founders’ Hall over in St. Johnsbury.’ I was twelve; it would be mid-to-late ’70s. ‘Tom, I don’t give a shit what you have to say. You’re drunk right now.’ And I think my father was. I think it was during the noon hour, probably in the summer. That’s why I was home. ‘You’re going now, and that’s it. If you don’t, then don’t bother coming back to work. You’ve got a family here; you’ve got a wife that loves you; you’ve got kids that are crying.’ It was quite a scene, as I remember. Off he went. I think it was thirty days. It helped my dad; he relapsed and had all those type things. But it was certainly something that I remember about Jimmy. He ruled with an iron fist, but he had a heart for those he wanted to have a heart for. For whatever reason, he had a heart for my dad.”

At a time when there were few if any female executives in the paper industry, self-proclaimed male chauvinist Jim Wemyss promoted Shirley MacDow to vice president of Diamond International. MacDow had graduated from high school at age seventeen in 1951. She immediately went to work at the mill as a clerk, earning seventy-two cents an hour, at a time when the minimum wage for women in the union was eighty-five cents. She never attended college or earned an MBA, although she took some correspondence courses over the years.

Wemyss recalled giving her more and more responsibility in the early years. “Shirley was schooled something like me. I said, ‘Do it.’ ‘Well, how do I?’ [Raises voice] ‘Do it!’ Then I’d kind of watch her. If you give people confidence, they do well. The day I made her a vice president, she walked into my office and started asking me some questions. I said, ‘What the hell are you asking me for? Do it!’ She said, ‘I might make a mistake.’ I said, ‘Join the club. I’ve made a lot of them’ [laughs]. That’s the only way you learn.” MacDow said her gruff boss never second-guessed her: “I can never remember him saying, ‘Why did you do that?’ Or, ‘How come you made that decision?’”

“I guess something within me was determined that I was going to be not just an invoice clerk,” MacDow reflected. “I wanted to do more than that. If there was an opportunity within the office, I did it; I took whatever job there was next. I wanted to be involved in everything. So I kept pushing away.” What made him decide to promote you? “I guess it was because I was doing those things and actually without any recognition until somebody said, ‘Who’s in charge of the office here?’ and all of a sudden, I’m the office manager; I’m the sales manager and whatever else you want to call me. Just sort of materialized. It wasn’t easy, but I have to say, bottom line, that I did enjoy it, or I wouldn’t have put up with a lot of the tough times when the men didn’t want any part of me, didn’t want to listen to anything I had to say, even if it was a good idea. I had to work through it. It was tough.”

Several male managers resisted taking orders from a woman. “I had to work probably twice as hard to establish the fact that if I made a decision, it was the right one,” MacDow said. “I didn’t just willy-nilly say, ‘This is the way it’s going to be.’ I had to really work at, ‘What should we do here, and how should we make this work?’ Because I was the female that was being watched, targeted. Over the years it got better, but it never got totally better even until after I retired. Boy, those first twenty years or so, wow!”

MacDow described herself as “a very detail person.” To defend against the hostility of some male subordinates, she said, “I always kept notes of everything on the decision that I made. I wrote who I checked it with. It saved my neck a lot of times because they always were accusing me of doing something that didn’t make any sense, just to get back at me because I was a female.”

On one occasion a male manager stormed into Wemyss’s office to demand he fire MacDow: “He lit into Mr. Wemyss. I’m standing there because I knew you don’t light into Mr. Wemyss, and I thought he was going to throw him bodily out the door. Well, he didn’t last much longer after that [laughs]. No one ever said to Mr. Wemyss, ‘You will do this or do that.’ He was the boss.”

One of MacDow’s most important jobs was “gatekeeper” for Jim Wemyss. “I made sure that people calling in, if it was somebody that I thought he should talk to, they could. [Otherwise], I just took care of it, or sloughed it off. I think any good right-hand person would do what I did as far as handling the life of the CEO.” Her job was to assure that his time was used efficiently: “Don’t bother us with piddling things.” For her efforts, she earned some nicknames. “You were known as the Dragon Lady,” Jim Wemyss teased. “Other words, too,” she replied. “Not quite so nice.”

She recalled her maternity leave in 1969: “I worked up until I had to go to [the medical center in] Hanover because I had some problems. Then I was back home in about five or six days. They brought my typewriter to the house. I had probably only another week at home, and then I went back to work. When I walked in the door, Mr. Wemyss was standing there with a bunch of papers in his hands. I thought he was there to say, ‘Welcome back.’ Instead, he said, ‘These need to be typed up today.’ Maternity leave—what’s that? [laughs].”

Did Jim Wemyss ever say “good job” to Shirley MacDow? “As far as ‘good job,’ forget it. No kudos. No, no, no, no. no. Not ever, never, to this day. Well, maybe the last two or three years [laughs].” Was his way of saying “Good job” to give you greater responsibilities? “Yeah. Now that’s probably the bottom line right there. He would just heap on more, not that I didn’t absorb it, because I never backed away from anything.”

AT THE CONCLUSION of our public interview in 2011, Wemyss, then eighty-five, said: “All you people, I always considered you—whether you believe it or not—were part of my family. The greatest joy I had was driving around here on a school day and seeing the playground full of kids screaming and running, and going around Sunday and seeing you people fighting to get into your churches, and saying, ‘That’s a good thing. That’s a good thing.’”