The nail-biting trip on the Little Juniata marked the second time George De Long’s life had been altered by ice. The first time, a group of teenage schoolmates pummeled him with ice and snowballs.

De Long had spent his childhood in “great seclusion”; his mother wouldn’t let him swim, skate, boat, or do just about anything a boy in Brooklyn, New York, would do for fun in the 1850s. She made every effort to “shield him from danger and accident.”

George rushed home from school every day, ignoring taunts from other kids. One winter afternoon, those taunts included a bombardment of ice. A chunk hit him squarely in the ear, causing enough damage that he spent the next two months at home.

Restless and longing for freedom, De Long started reading about U.S. Navy heroes from the War of 1812. He wanted that kind of adventurous life for himself, so he applied for an appointment to the U.S. Naval Academy and was accepted. His parents refused to let him go. They offered him three options: become a doctor, a lawyer, or a priest.

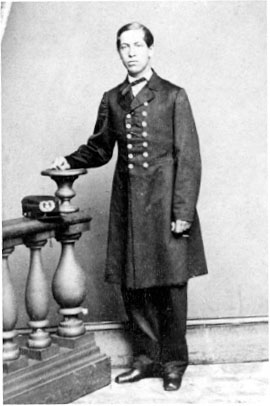

De Long was a youthful midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy when this portrait was taken.

It was easy to convince his squeamish mother that a career in medicine was a bad choice due to “the incessant risks which a doctor ran of contracting a great variety of contagious diseases.” The same was true of the priesthood, which demanded contact with the sick and dying.

De Long enrolled in courses at a local college, spending his spare time reading books of adventure to satisfy his “almost uncontrollable longing for the sea.” He also started working for a lawyer to see if he’d like that profession for himself.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the lawyer joined the Union army. Seventeen-year-old De Long begged his parents to let him accompany his boss. They refused. But when he again asked for permission to enroll in the Naval Academy, they didn’t stop him.

De Long graduated from the academy in 1865, shortly after the end of the Civil War. His first assignment was aboard the U.S. Steamer Canandaigua. Entering the steerage room that would be his home for the next few years, he was surprised to find that there weren’t enough sleeping berths. “To me this seemed altogether wrong,” De Long said. “Each midshipman should have his own bunk.” Still a naive young man, De Long spoke to some officers about his concern.

“That’s right,” they told him, recognizing his gullibility. “The thing should be attended to.” They sent him to see the admiral.

De Long found the admiral “sitting erect at his desk, making a striking picture with his white hair and sharp black eyes.”

Cap in hand, De Long stepped forward and said, “Admiral, I am Midshipman De Long of the U.S.S. Canandaigua. Sir, I have been inspecting my quarters on board and I find only two bunks in the steerage for four midshipmen. I came, Sir, to ask you to have two more berths put in before we start.”

The admiral’s response was blunt. “Well, Midshipman De Long of the U.S.S. Canandaigua, I advise you to return on board the U.S.S. Canandaigua and consider yourself very lucky that you have any bunks at all in the steerage.”

De Long left sheepishly. But the admiral must have admired his grit. He had the two bunks added.

De Long spent three years on the Canandaigua, which took him on peaceful missions through the Mediterranean Sea and along the coast of Africa. On a stop in Europe, he met Emma Wotton, the daughter of an American sea captain. Though Emma’s father resisted De Long’s efforts to court his daughter, seventeen-year-old Emma found De Long “dashing” and admired his “adventurous spirit.” She was struck by his grayish-blue eyes and his drooping mustache, which made him appear older than he was.

After just a few short conversations, the love-struck De Long told Emma that “I feel as though I had known you always—as if I had simply been waiting for you to appear.” He promptly asked her to marry him, but Captain Wotton insisted on a two-year waiting period. De Long spent most of that time away at sea, worrying that Emma might find someone else to marry. Though Emma had given him a pearl-encrusted gold cross, her enthusiasm for an engagement hadn’t matched his. “I had as strong a will as he and was not to be swept off my feet,” she admitted.

De Long wrote long letters to Emma while he was away, and eventually her affection grew to match his. They married on March 1, 1871, and Emma gave birth to a daughter, Sylvie, that December. Though voyages kept De Long away from home for long periods of time, Emma was used to absences. “My childhood was dominated by the sea,” she said.

So Emma didn’t object when James Gordon Bennett Jr. asked De Long to lead a trip to the North Pole. De Long studied the writings of ship captains and scientists, including the esteemed geologist August Petermann, the world’s foremost maker of maps. Petermann believed that the warm Pacific Ocean current known as the Kuro Siwo was the key to reaching the pole. He said earlier expeditions had failed because they’d tried to reach the pole via the Atlantic Ocean instead of steaming through the Kuro Siwo.

Sylvie De Long

Petermann was considered the top authority on the Arctic—even though he’d never been there. One historian described Petermann as an “armchair rover,” since he’d hardly traveled anywhere outside his native Germany. Petermann based his theories on the findings of actual explorers, but he often distorted or misinterpreted what he learned. He claimed that the Kuro Siwo passed through the Bering Strait between Alaska and Siberia, working its way under the polar ice ring (or cutting a channel through it) and then warming the northern ocean. “The central area of the Polar regions is more or less free from ice,” Petermann insisted in an interview with the Herald. He confidently predicted that an expedition could reach the polar sea and return in as little as two months.

Also enticing to Bennett and De Long was the expectation of an unexplored northern continent. Native peoples of Alaska and Siberia told legends about a great land to the north. Russian explorer Baron Ferdinand von Wrangel led several expeditions in the 1820s searching for it but wasn’t successful. In 1867, explorers finally glimpsed the southern edge of what became known as Wrangel Land, a large island off the coast of Siberia. With no basis for his claim, Petermann said Wrangel Land was a continent that extended all the way to Greenland.

The next step for De Long was to find a worthy ship. Bennett promised to pay for the ship, the crew, and all provisions, although De Long insisted that the U.S. Navy should have authority over the voyage. It was an arrangement with benefits for him and the Navy: De Long had no desire to give up his naval career, and now he could remain a Navy officer while pursuing his dream of reaching the North Pole. His crew would be subject to military rules and discipline, and he could also select other Navy officers to sail with him. What’s more, the Navy would gain valuable knowledge about the northern ocean at little cost.

De Long found a suitable ship named the Pandora in England. Bennett purchased the 145-foot steamer, and De Long oversaw repairs in preparation for an Arctic voyage to begin in 1879.

The ship was renamed the Jeannette—after Bennett’s sister. De Long piloted it on a six-month trip around South America. Strong-willed Emma insisted that she and their seven-year-old daughter make the trip, too.

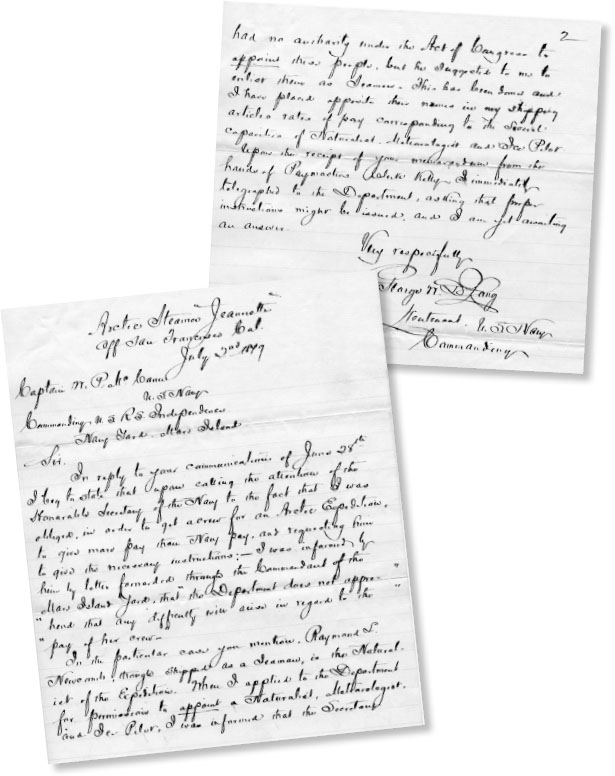

De Long sent this letter to the secretary of the U.S. Navy while docked in San Francisco, clarifying how the crew would be paid.

The crew included men that were handpicked by Bennett. Alfred Sweetman, from England, was a skilled carpenter who’d worked on Bennett’s yachts and proved to be highly reliable. John “Jack” Cole—a short, agile Irishman—was a nimble climber and declared by Bennett to be “worth his weight in gold.”

After traveling eighteen thousand miles, the Jeannette reached San Francisco two days after Christmas in 1878. Emma later wrote that the voyage with her husband and Sylvie had been “the happiest period of my life.”

In a navy yard north of San Francisco, the ship took on larger coal bunkers, new boilers and pumps, new propellers, and a full range of tools, ropes, rifles, compasses, and Petermann’s maps and charts. Workers caulked, painted, and fortified the ship with thick lumber to protect it from the inevitable pounding of polar ice.

De Long chose his officers, but he put the hiring of most of the crew in the hands of Lieutenant Charles W. Chipp, the ship’s executive officer. Chipp had been with De Long on the Little Juniata expedition, and the two men valued each other’s experience and friendship.

The hype surrounding the expedition attracted sailors of all types looking for a berth; more than 1,200 applied for twenty-four spots. De Long’s orders to Chipp reflected many of the prejudices of the day: “Requirements for crew: Single men perfect health; considerable strength; perfect temperance; cheerfulness; ability to read and write English; prime seamen of course. A musician, if possible. Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes preferred. Avoid English, Scotch, and Irish. Refuse point blank French, Italians, and Spaniards.”

An exception to the no-Irish rule was Jack Cole. Cole, age forty-one, had been working at sea since he was thirteen.

Departure was scheduled for the early summer of 1879.

“Our outfit is simply perfect,” De Long told Bennett, “whether for ice navigation, astronomical work, magnetic work, gravity experiments, or collections of Natural History. We have a good crew, good food, and a good ship, and I think we have the right kind of stuff to dare all that man can do.”