Captain De Long never rested easy. Long after midnight, on January 19, he sat in his quarters, perhaps thinking ahead to the following summer, when the Jeannette might finally break free from the ice. Summer seemed a long way off—the sun hadn’t risen above the horizon for more than two months in what seemed like an endless, dark winter.

In the back of the captain’s mind, as always, was a nagging awareness that the ship might crash to the bottom of the ocean before summer came. The ice had been relatively quiet lately, “but this horrible uncertainty grows wearisome.”

De Long grimaced as a familiar loud noise rocked the ship. “I know of no sound on shore that can be compared to it,” he wrote. “A rumble, a shriek, a groan, and a crash of a falling house all combined might serve to convey an idea of the noise with which this motion of ice-floes is accompanied.”

The new assault sounded like the cracking of the ship’s frame. De Long rushed to the deck to find the cause of the noise, but all seemed calm. “The ice was perfectly quiet, and no evidence of anything wrong could be found about the ship.” So he went to bed.

By morning, the ice was “groaning and grinding,” squeezing the ship and piling up around it and under it. But the crew didn’t worry about the potential danger. They rushed out onto the giant blocks of ice like excited kids. “With light hearts the men dispersed themselves upon the ice,” Melville wrote, “climbing the slopes of the marble-like basin, leaping from block to block, clambering up pinnacles and tumbling down with laughter … all hailing and shouting in boyish glee,—when, suddenly, the dread cry of ‘Man the pumps!’ put a check to their short-lived sport, and sent every one scudding back.”

Two inch-wide streams of water flowed into the Jeannette’s bilges, and the water was already three feet deep in places.

The ship was equipped with several pumps, but only one worked. Crew members hustled to move flour and other provisions from the storeroom, and others used hand pumps to try to keep ahead of the leaks. William Nindemann, one of the ship’s carpenters, led the way, working frantically in the icy water.

“The temperature at this time was about 40° Fahrenheit below zero, and as the water rushed into the hold it almost instantly froze,” Melville wrote. “Pouring steadily in, it crept above the fire-room floor, and fears were entertained that it might reach the boiler furnaces before the steam-pumps could be started.”

Men slogged water from the hold in a barrel. “Time meant life or death,” Melville warned.

Pumping and hauling the water wasn’t enough. The leak had to be slowed. Nindemann stood in knee-deep water, filling the cracks with oakum and tallow. “As fast as he stuffed it in below the water came out above,” De Long wrote. Nindemann never seemed to tire or feel pain, and the captain called him “as hard-working as a horse.” With the Jeannette in danger of sinking, he and fellow carpenter Alfred Sweetman didn’t rest for days.

Melville went to work to repair a steam-powered pump, “for men cannot stand pumping from now till spring.” He succeeded, working around the clock while others packed sledges with food, sleeping bags, and other supplies in the expectation that they might soon abandon the ship.

By hand and by steam, the pumps rid the ship of 3,300 gallons of ice-cold seawater per hour. But that only kept the water from getting deeper. Nindemann and Sweetman patched with plaster of Paris and ashes.

“We do not gain much on the water,” De Long wrote, “but then the water does not gain on us.” He made a notation in his journal to recommend Nindemann and Sweetman for Congressional Medals of Honor for their bravery and unending hard work.

De Long knew that the situation could not continue. “Pumping by hand will use up my crew, and should we be obliged to leave the ship in a sudden smash-up, I would have an exhausted body of men to lead over the ice two hundred miles to a settlement. If the water freezes in the ship, more damage may be done in a day than we could repair in a month.”

Fortunately, the repairs worked. A week after the leak began, Melville calculated that they’d reduced the flow to 2,250 gallons per hour. With the steam pump working full blast, the hand-pumpers could take some breaks. But it took fuel to fire the steam pump, reducing the coal supply by a worrisome amount.

The slowing of the leak was not the only welcome news. On January 26, De Long recorded “the reappearance of the sun!” for the first time in seventy-one days. “Although the glare was trying to the eyes, making me blink like an owl at first, I could not get enough of the pleasant sight.”

Melville rigged up another pump, but its engine wasn’t powerful enough to make much difference. So he adjusted the pump with melted tin and a pair of plungers. The new scheme worked, and it took some of the pressure off the boilers.

“At last we have succeeded in reducing our fearful expenditure of fuel to a reasonable amount; 400 pounds of coal a day will now run our two steam-pumps, and that is much more comforting than burning 1,000 to 1,200 in the main boiler furnaces,” De Long wrote. Melville also built a windmill that helped power the pumps. Still, they used much more coal than expected.

“Verily, all our troubles are coming upon us at once,” De Long complained, listing among those troubles the fact that Danenhower’s eye condition was rapidly declining. This forced Dr. Ambler to probe and cut to relieve the pressure in the eye and ease the constant flow of pus. Ambler suspected that Danenhower suffered from sexually transmitted sy philis, which could also explain his past history of mental illness.

William Nindemann, ship’s carpenter

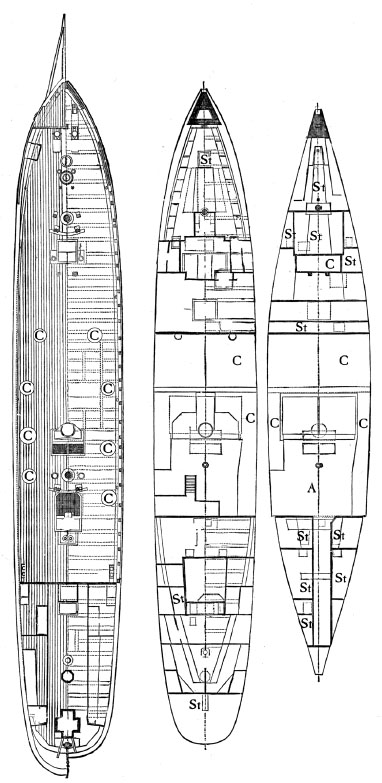

This cross section of the Jeannette shows the main deck (left), the berth deck (middle), and the hold (right). Flooding occurred primarily in the hold, including the engine room (A), coal bins (C), and storerooms (St).

Also, Jerome Collins, James Gordon Bennett’s reporter, had turned out to be combative and inept and was always in De Long’s doghouse. None of the lighting or telegraph equipment he’d brought on board had worked, so he’d sent no reports to the Herald after leaving Alaska. Collins also refused to exercise or pay attention to De Long’s orders. He annoyed the other men with his constant puns. (Why won’t the Jeannette ever run out of fuel? Because we have Cole on board!)

Lieutenant John Danenhower

Overall, every inch of the ship was “wretchedly wet and uncomfortable.” Worse, from De Long’s point of view, was the distress of accomplishing little to advance science or navigation. He came to the sickening conclusion that the leaks would prevent the Jeannette from reaching the North Pole. “All our hoped for explorations, and perhaps discoveries this coming summer, seem slipping away from us, and we seem to have nothing ahead of us but taking a leaking ship to the United States.”