De Long stepped into a dinghy and shoved off into the narrow stream. He blew out his breath in a cold mist, rowing slowly to avoid crashing into the channel’s icy walls. Though reaching the open ocean was out of the question, the captain enjoyed exploring the small streams that opened up in the ice. Most summer afternoons, he set out alone in the dinghy, searching for an escape route for the Jeannette.

He knew that the channels would soon freeze over, forcing him and his crew to spend a second winter in the ice pack. That was disappointing but not unexpected. Still, it had been more than a year since he’d seen his wife and daughter. Nearly a year had gone by since he’d stood on land.

It was a Sunday. August 22, 1880. De Long’s thirty-sixth birthday.

The stream was so narrow that in some spots he could use only a single oar. Deliberately he poked along through the “winding and intricate” channel, searching for cracks and openings, “watching the wasting of the ice, and making out in my own mind where a break may occur by connecting the several holes wasted clear through to the deep water.”

De Long was bewildered by the massive expanse of ice, which seemed more permanent than anyone had believed. “Is this always a dead sea?” he wondered. “Does the ice ever find an outlet?” He’d witnessed nine months of ice growth in the long Arctic winter, and the modest melting during this short hint of summer “by no means equals the growth in nine months.” If more ice grew every year than could melt, “it would require but a few years to make this a solid mass, and so take up this Arctic Ocean entirely.” Forget about a warm polar sea.

De Long rowed for about a mile, but because of all the twists and turns in the mazelike channel, he was never more than five hundred yards from the Jeannette. He found the solitude a welcome break from the demands of captaining the crew.

He gazed ahead at the seemingly unending ice. How far did it stretch? “It is hard to believe that an impenetrable barrier of ice exists clear up to the Pole,” he wrote, “and yet as far as we have gone we have not seen one speck of land north of Herald Island.”

The dinghy entered a long, thin opening, “which obliged me to scull, and facing aft, to use both hands.” Something caused De Long to look back over his shoulder, “and to my astonishment found my eyes resting on a bear not a hundred feet off, and who, judging by his looks, was quite as astonished as I was.”

De Long looked for a way to escape, but the prospects were bleak. There was no water between him and the bear, and the piles of ice would make it impossible for him to outrun the animal. “I was jammed in a narrow lead and he stood looking at me.”

De Long was shocked when he came face-to-face with a polar bear.

Then the bear stepped toward him.

“On board ship there!” De Long yelled. “A bear! a bear!”

No one answered.

The bear had advanced to within fifty feet—“so close that I could see distinctly where the short hair ended at the edge of his beautiful black nose. Hearing my shout he stopped, and looked at me wonderingly. I again shouted, ‘On board ship there!’ and somebody answered, ‘Halloa.’ Mentally calculating my chances I again yelled, ‘A bear! a bear!’”

De Long lifted an oar, ready to fight the bear if it attacked. “He stood still, however, and looked as if he could not quite make me out.”

The bear hesitated. The barking of a pack of dogs—turned loose from the ship and answering De Long’s call—caught the bear’s attention. “He gazed at them until, judging they meant him no good, he turned and ran, so fast that before the men and dogs could get on his trail he was out of range.”

De Long recorded the event in his journal that evening: “Lesson for me: ‘Never go away from the ship without a rifle.’”

Within a week of De Long’s encounter with the bear, any lingering hope of a warm summer had faded away. De Long resigned himself to a second winter in the ice, but “Shall we be any more successful when it has passed?” Careful measurements showed that the Jeannette had drifted about 140 miles north from the point where it first had been locked in nearly a year before. De Long gloomily speculated that with a similar drift through the next year, “we shall then be 800 miles from the Pole, and 500 miles from a Siberian settlement, with a disabled ship, no fuel, and perhaps as immovably jammed as now.”

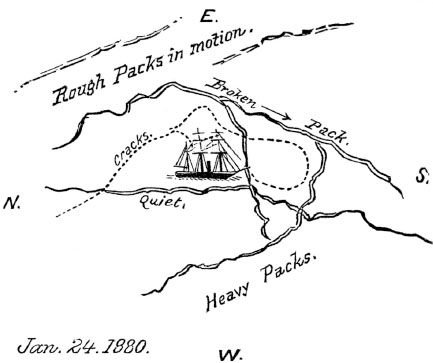

Newcomb’s sketch shows many of the cracks that formed streams in the ice pack.

And though the food and fuel would never last, De Long imagined the possibilities of a deserted ship continuing in a never-ending northward spiral. “In six additional years we should reach the Pole. But what is the use of figuring it up—a man might as well attempt to demonstrate by mathematical calculation the day of his death. Let us deal with the present.”

SEPTEMBER 2D, THURSDAY

A cheerless and gloomy day. The usual fog in the forenoon, and in the afternoon until midnight an almost steady fall of very light snow. In one day we seem to have jumped into winter.

SEPTEMBER 5TH, SUNDAY

One year in the ice! and we are only one hundred and fifty miles to the northward and westward of where we entered it…. Anxiety, disappointment, difficulties, troubles, are all so inseparably mixed that I am unable to select any one for a beginning.

At six A. M. Chipp heard a grinding of ice to the eastward, and I suppose we shall have the satisfaction now of waiting for the repetition of the anxious times of last winter, not knowing how soon we may have pandemonium around us. In order to provide for any emergencies we can do nothing more than getting provisions on deck, convenient for heaving on the ice, and we therefore devote the day to this occupation.

The snow would give a metallic ring at each footfall loud enough to interfere with ordinary conversation. Standing near some of these conflicts between grinding floes one first would realize the pressure by the humming, buzzing sound; then a pulsation is felt … right under foot, with a report like a big gun…. It upheaves you, lifts you with it and you must step back to a safer place. I have often taken these rides. There is a wonderful fascination about it.