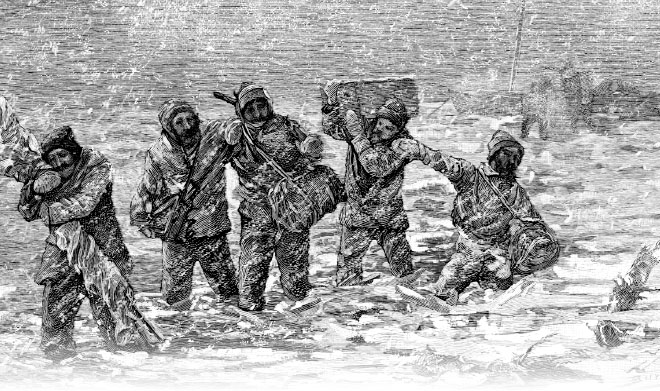

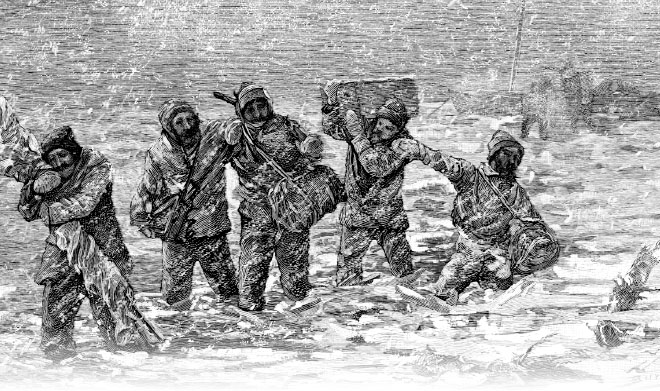

Members of De Long’s party wade to shore in the Lena Delta.

After the two cutters and the whaleboat separated on September 12, De Long seemed to have lost much of his spirit. While his crew battled to stay afloat for a day and a half on the raging ocean, the captain climbed into his sleeping bag and barely moved. He complained to Dr. Ambler about his cold hands and feet, and developed “a nervous chuckle in his throat.”

De Long made only a few notations in a small notebook until September 17, when the crew finally reached land. They found themselves in a muddy, treeless delta 120 miles west of the spot where Melville’s whaleboat had gone ashore. De Long barely mentioned the other boats, except to note that they hadn’t been seen.

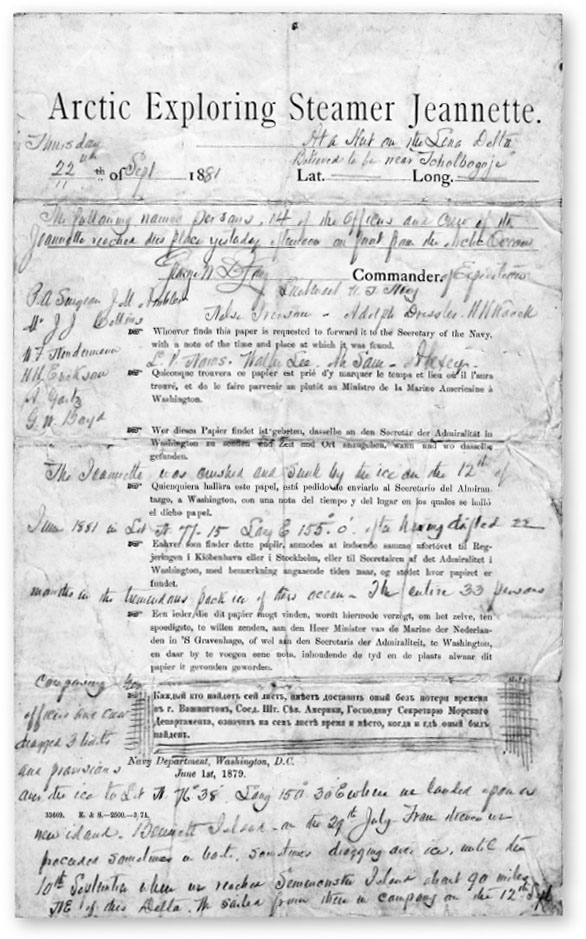

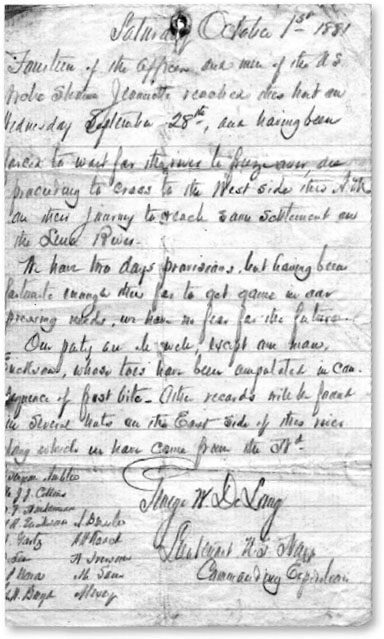

He wrote a letter with the nub of a pencil and left it in an instrument box above the riverbank:

Monday, 19th of September, 1881.

LENA DELTA

The following named fourteen persons belonging to the Jeannette (which was sunk by the ice on June 12, 1881, in latitude N. 77° 15’, longitude E. 155°) landed here on the evening of the 17th inst. [of this month], and will proceed on foot this afternoon to try to reach a settlement on the Lena River: De Long, Ambler, Collins, Nindemann, Gortz, Ah Sam, Alexey, Ericksen, Kaack, Boyd, Lee, Iversen, Noros, Dressler.

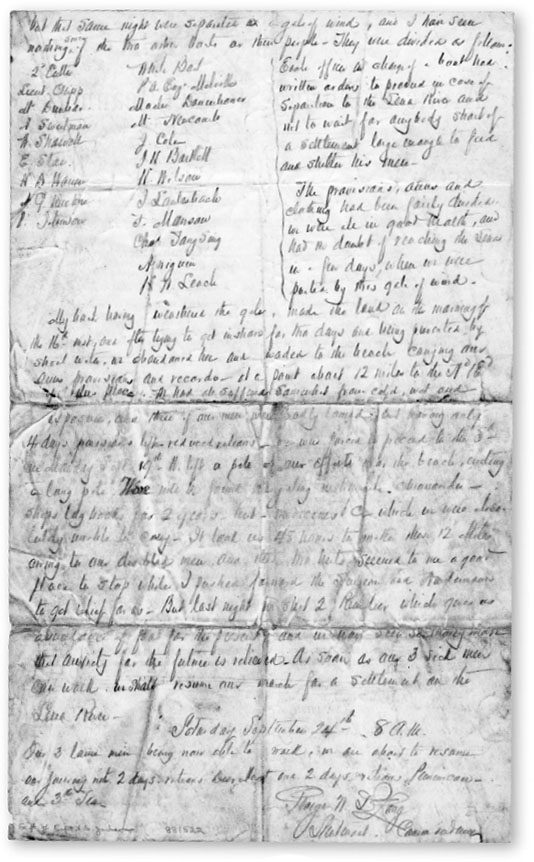

A record was left about a half mile north of the southern end of Semenovski Island buried under a stake. The thirty-three persons composing the officers and crew of the Jeannette left that island in three boats on the morning of the 12th inst., (one week ago). That same night we were separated in a gale of wind, and I have seen nothing of them since. Orders had been given in event of such an accident for each boat to make the best of its way to a settlement on the Lena River before waiting for anybody. My boat made the land in the morning of the 16th inst., and I suppose we are at the Lena Delta. I have had no chance to get sights for position since I left Semenovski Island. After trying for two days to get inshore without grounding, or to reach one of the river mouths, I abandoned my boat, and we waded one and one half miles ashore, carrying our provisions and outfit with us. We must now try with God’s help to walk to a settlement, the nearest of which I believe to be ninety-five miles distant. We are all well, have four days’ provisions, arms and ammunition, and are carrying with us only ship’s books and papers, with blankets, tents, and some medicines; therefore, our chances of getting through seem good.

GEORGE W. DE LONG,

Lieut. U. S. Navy Commanding.

De Long left detailed notes like this one at several places along his route. one at several laces alon his route

The men were sick and injured, with blue, frozen feet. But after two days of rest, they left the cutter behind and began walking. They didn’t even bring their sleeping bags; instead, they cut them up to make foot coverings. But De Long made sure the ship’s charts, logbooks, papers, and journals were hauled.

Their trip over land was much more difficult than the whaleboat’s travels on the river. Stumbling and groaning with the heavy loads, the men needed three fifteen-minute rests during the first two hours.

Petermann’s map was confusing and mislabeled. It showed a settlement named Sagastyr in two different places and did not show the larger village of North Bulun at all. So De Long aimed for the only nearby settlement that was on the map.

The captain finally agreed to stow a few of the books and records in a place where they could be retrieved if the men were ever rescued. Still, their progress was excruciatingly slow. Hans Ericksen, who had proved to be so strong when he accompanied Melville to Henrietta Island, “hobbled along a foot at a time,” wrote De Long, who continued to confide in his notebook. “Every one of us seems to have lost all feeling in his toes, and some of us even half way up the feet,” he noted. “That terrible week in the boat has done us a great injury.”

William Nindemann stayed alongside his friend Ericksen and helped him walk. Both men were Europeans, Nindemann from Germany and Ericksen from Denmark.

Dr. Ambler wrote that Ericksen’s feet “look very bad … but we must move on as every mile brings us nearer striking distance of a settlement. We cannot offer to carry him as all the men are loaded to their full strength, & as long as he can walk he will have to do so.”

De Long kept his eye on poor Snoozer—the last remaining dog—who trotted by his side. The pemmican was almost gone, and except for one stringy seagull, they hadn’t been able to shoot any game.

Snoozer could provide a couple of meals for the fourteen men. After that?

Ericksen collapsed on the trail. “I cannot go any further,” he whispered to Nindemann. De Long scolded Ericksen and lifted him to his feet. Ambler declared that “no man will be left alone.”

Ericksen hobbled for another mile. The men built a fire and spent a miserably cold night under a heavy snowfall. They had only one tent, but it couldn’t possibly shelter all of the men. They cut it in half for two makeshift blankets.

The next day, fresh snow revealed a large number of reindeer tracks, which brightened the men’s spirits. Even Ericksen was able to walk again, and by midafternoon they’d reached two empty huts. Was this the “settlement” on De Long’s map? If so, they were nearly ninety miles from the next one!

De Long “concluded that this was a suitable place to halt the main body, and send on a couple of good walkers to make a forced march to get relief.” The rest would stay behind “to eke out an existence” while waiting to be rescued.

De Long chose Nindemann and Dr. Ambler to leave the next morning. Thirteen men crawled into the huts. One stayed out.

Long after dark, De Long heard a familiar voice. “All asleep inside?”

Alexey’s hunting skill provided De Long’s group with lifesaving reindeer meat.

Alexey stuck his head into De Long’s hut. He held out a hindquarter of meat. “Captain, we got two reindeer,” the expert hunter said.

The grateful men “cried enough,” and rebuilt the fire. Each was soon gobbling down a pound-and-a-half portion of Alexey’s reindeer.

“The darkest hour is just before the dawn,” wrote De Long, regaining his old enthusiasm. He rethought his plans. They had warm huts and fresh meat, so why send anyone ahead now?

The next morning, Nindemann, Alexey, and five other men dragged in the two reindeer. De Long figured they had enough meat for several days of recovery in the huts, and in the meantime they might shoot more game. He claimed that the ailing men were getting better, or at least no worse.

De Long took account of the meat: “Meat free from bone, fifty-four and a half pounds; meat on the bone, fourteen pounds; bones for soup, fifteen pounds.”

All fourteen men set off together on September 24. De Long left behind his rifle “as a surprise to the next visitor.” It was just too heavy to carry.

They forged along for a few rough miles a day. Ericksen developed a painful foot ulcer, exposing the muscles and tendons. The men were soon down to a handful of pemmican “and the dog.” Then eleven deer came into sight, and only ten escaped.

“Saved again!” De Long proclaimed.

But the captain finally had to admit that Ericksen’s life was in danger because of his infected feet. Forcing him to continue walking would probably kill him, but if they stayed put, they’d all likely die of starvation.

Despite the abysmal conditions, De Long wrote on October 1, 1881, that “we have no fear for the future.”

De Long turned to Nindemann, his most reliable worker, and asked him to make a sled. Nindemann found a plank of wood. “I had nothing else but an old dull hatchet,” he said, but he managed to construct a workable sled.

Dragging Ericksen, the men pressed forward. They found a hut and made a roaring fire. Ericksen groaned in his sleep, murmuring words in English, German, and his native Danish.

After they’d loaded up the next day, Nindemann went to the hut for Ericksen. Ten black nubs on the snow caught his attention. He looked at them closely, then stepped back as he recognized what they were. “I saw some toes lying outside of the hut,” Nindemann recalled. Dr. Ambler had cut the dead, frostbitten digits from Ericksen’s feet.

Snoozer died on October 3, victim of a carefully aimed gunshot. De Long could not bring himself to eat the resulting stew, though most of the men did.

Then Ericksen “departed this life” at 8:45 a.m. on October 6. The ground was frozen solid and there were no tools to dig with anyway. “The seaman’s grave is the water,” De Long said, “and therefore we will bury him in the river.” They carried Ericksen out on the ice and “buried” him in a hole.

Nindemann carved these words into a board and fastened it on the hut where Ericksen died:

H. H. ERICKSEN,

Oct. 6, 1881,

U.S.S. Jeannette

Ericksen’s clothing was shared by his shipmates, who also kept his Bible and locks of his hair. “Peace to his soul,” wrote Ambler.

Without Ericksen, the men could move a little faster, but hunger and deep snow soon made walking almost impossible. More men were breaking down, and De Long feared that they’d soon join Ericksen.

“Nindemann, do you think you are strong enough to make a forced march” to the settlement? De Long asked.

“He told me I could take any man I wanted except Alexey,” Nindemann recalled. Alexey was too valuable as a hunter; his skills provided the best chance the remaining men had of surviving. So Nindemann chose Louis Noros because Noros could “get over ground as well as any one.”

“If you find assistance come back as quick as possible,” De Long said, “and if you do not you are as well off as we are.”

The men said a tearful good-bye, shaking hands with everyone and receiving three cheers. They trudged off through a foot and a half of fresh snow, carrying two blankets, a rifle, and forty rounds of ammunition, but no food.

Noros kept his eyes on “a high, conical, rocky island, which rose up out of the river.” That landmark would help him remember where they’d left their companions.

De Long and the others limped forward for a few miles, following the tracks left by Nindemann and Noros. They prayed that those two would reach a settlement and send back help.

OCTOBER 10TH, MONDAY.

Eat deerskin scraps. Yesterday morning ate my deerskin foot-nips…. All hands weak and feeble, but cheerful. God help us.

OCTOBER 11TH, TUESDAY.

S. W. gale with snow. Unable to move. No game.

OCTOBER 12TH, WEDNESDAY.

For dinner we tried a couple of handfuls of Arctic willow in a pot of water and drank the infusion…. Hardly strength to get fire-wood.

OCTOBER 13TH, THURSDAY

We are in the hands of God, and unless He intervenes we are lost. We cannot move against the wind, and staying here means starvation. Afternoon went ahead for a mile, crossing either another river or a bend in the big one. After crossing, missed [Walter] Lee. Went down in a hole in the bank and camped. Sent back for Lee. He had turned back, lain down, and was waiting to die. All united in saying Lord’s Prayer and Creed after supper. Living gale of wind. Horrible night.