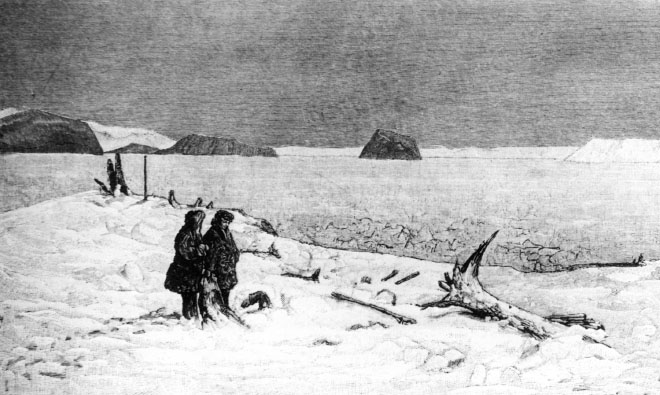

Melville was determined to reach the spot where he’d ended his search months earlier. He relied on Nindemann’s memory of the area, and on Bartlett’s strength. But Siberia is vast, and the winter weather severe. “To the southward of the mountain range absolute stillness reigned, and the snow-fall was constant and heavy,” Melville wrote. But as they traveled north, “I at once felt a change in the atmosphere. Whereas to the southward everything was as calm as the quiet of death, in front of us a gale was already blowing.”

It took the men three weeks to reach Bulun, where they were stormed in for another month. They finally set out in miserable conditions. Snow was piled so high that Nindemann couldn’t recognize the terrain. Eventually they reached the high, rocky island that Noros had identified as a landmark. On March 24, Nindemann spotted a broken flatboat near the river. This was the spot where he and Noros had first camped.

Nearby, four poles stuck out of a snowbank. They were lashed together, and a Remington rifle hung from the lashing. Melville ran toward it and fell, cutting his face. He recognized the rifle as Alexey’s.

Melville and Nindemann found De Long’s body partly covered by snow.

Minutes later, Melville discovered a firebed on a slope. He bent to pick up a copper kettle from the snow, and “I caught sight of three objects at my very feet; and one of these, the one I was about to step over—was the hand and arm of a body raised out of the snow.”

Melville instantly recognized De Long’s coat. “He lay on his right side, with his right hand under his cheek, his head pointing north, and his face turned to the west,” Melville wrote. “His feet were drawn slightly up as though he were sleeping; his left arm was raised with the elbow bent, and his hand, thus horizontally lifted, was bare.”

A few feet behind De Long, Melville found the small notebook, or ice journal, in which the captain had recorded his most recent entries. With his final bit of strength, De Long apparently threw it back to ensure that it didn’t burn in the fire. He never lowered his arm.

In the pockets of De Long’s coat, Melville found two pairs of eyeglasses, the captain’s silver watch, a whistle, and the blue pouch with the lock of Emma’s hair. The pouch also held Emma’s gold cross set with three pearls and the little porcelain doll De Long had purchased in Alaska for Sylvie. The doll was wrapped in a tiny blanket.

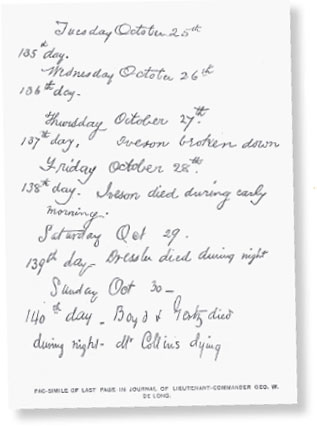

Melville started reading from the back of De Long’s journal, learning the order in which the men had died. The last entry, dated October 30, said “Mr. Collins dying.”

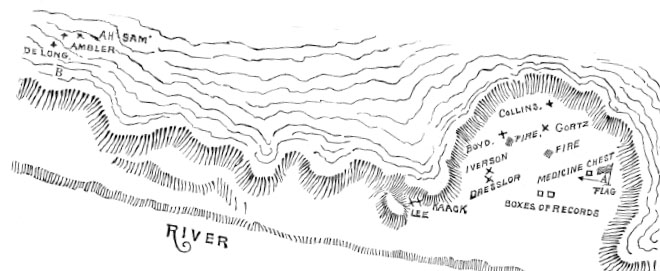

A few feet from De Long’s body, Ah Sam lay faceup with his hands across his chest. He’d probably been placed that way by the captain and the doctor. He wore a pair of red knit socks with the heels and toes worn away. Few of the other bodies had any footwear. Most had bits of blanket or tent tied with ropes around their limbs, in an attempt to keep from freezing.

Among De Long’s possessions when he died was this tiny porcelain doll he’d purchased in Alaska for his daughter.

De Long recorded the deaths of his crew on the final page of his journal.

A medicine case and a few other items were scattered about, including the four-foot cylinder that held the ship’s charts and drawings.

Other bodies were found beneath the snow. Their clothing was scorched from lying so close to the fire. Collins clutched a rosary.

Dr. Ambler appeared to have died last. He gripped De Long’s pistol, which he’d taken from the dead captain to protect himself or to kill an animal for food if one came to feast on the bodies. Melville noticed blood on Ambler’s mouth and beard, and wondered if he’d shot himself. But there was no wound other than a small one on his hand. As he was dying of thirst, Ambler had bitten into his own thumb for liquid. “There he kept his lone watch to the last,” Melville wrote, “on duty, on guard, under arms.”

Melville discovered this letter that the dying doctor had written to his family:

On the Lena,

THURSDAY, OCT. 20TH, 1881.

To Edward Ambler, Esqr.

I write these lines in the faint hope that by God’s merciful providence they may reach you all at home. I have myself now very little hope of surviving. We have been without food for nearly 2 weeks, with the exception of 4 ptarmigans amongst 11 of us. We are growing weaker, and for more than a week have had no food. We can barely manage to get wood enough now to keep warm & in a day or two that will be passed. I write my brother to you all, my Mother, Sister, Brother Cary & his wife & family, to assure you of the deep love I now & have always borne you. If it had been God’s will for me to have seen you all again I had hoped to have enjoyed the peace of home living once more. My mother knows how my heart has been bound to hers since my earliest years. God bless her on earth & prolong her life in peace & comfort. May his blessing rest upon you all. As for myself, I am resigned & bow my head in submission to the Divine Will….

Your loving brother,

J.M. Ambler

No such letter from De Long was found. A page was missing from the captain’s notebook, but if he’d written a letter to Emma on it, it was lost. Melville searched for the missing page. He later told Emma that “he firmly believed it carried a message” for her.

This map shows where the bodies were found.

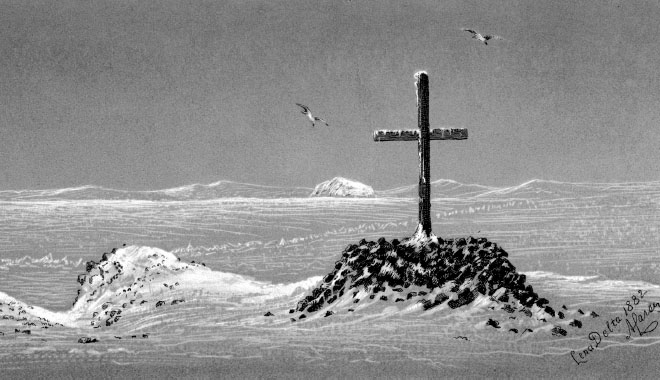

Melville, Nindemann, and Bartlett created this temporary tomb for the bodies of their shipmates.

“No doubt the Siberian winds had snatched it from my husband’s grasp,” Emma wrote. “It was never found.”

De Long’s notes showed that they were still alive at least ten days after Ambler wrote the letter. His final entry is dated Sunday, October 30, the 136th day since the company began walking away from the site of the Jeannette’s sinking. De Long wrote that Collins was dying. That would have left Ah Sam and Dr. Ambler as his only companions.

Melville, Nindemann, and Bartlett uncovered all the bodies except Ericksen and Alexey, the two men buried in the river. They tied everyone’s personal items in small bundles and labeled them. Then they made a temporary coffin from the broken flatboat and created a tomb for the men. Eventually, the bodies were transported to the United States.

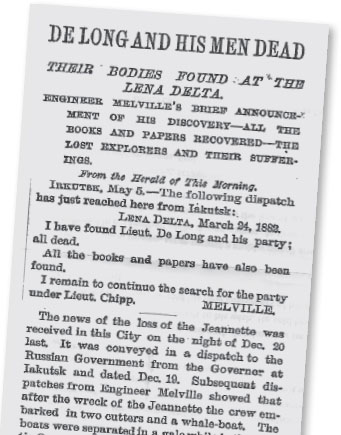

It wasn’t until May that Melville’s next telegram reached the offices of the New York Herald. It was published in the following day’s edition:

LENA DELTA, MARCH 24, 1882

I HAVE FOUND LIEUT. DE LONG AND HIS PARTY; ALL DEAD.

ALL THE BOOKS AND PAPERS HAVE ALSO BEEN FOUND.

I REMAIN TO CONTINUE THE SEARCH FOR THE PARTY UNDER LIEUT. CHIPP.

MELVILLE

Melville scoured the delta for any remains of Chipp, his crew, and the second cutter. That search proved fruitless. He finally returned home to the United States more than three years after first departing for the Arctic.

The New York Herald reported the grim news of the men’s deaths.