Thirty-three men embarked on the Jeannette’s Arctic journey to reach the North Pole. Twelve survived.

Most of the survivors testified during the Navy Court of Inquiry hearings to investigate the ship’s sinking, rescue efforts, and conduct of the officers and crew. Although John Danenhower may have told reporters “off the record” in Siberia that he disagreed with De Long’s decisions, on the witness stand he spoke highly of the captain and crew (except for Jerome Collins, who nearly everyone agreed was a troublemaker). Satisfied with the testimonies, top Navy officials concluded that the Jeannette had been well prepared and managed, noting that the crew “seems to have been a marvel of cheerfulness, good-fellowship, and mutual forbearance, while the constancy and endurance with which they met the hardships and dangers that beset them entitle them to great praise.”

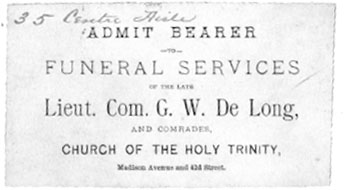

Only people with tickets could attend De Long’s funeral service.

De Long’s funeral procession—on February 22, 1884—drew huge crowds in New York City.

After their deaths, Alexey and Aneguin were honored with these medals from the U.S. Congress for their skills and bravery.

De Long’s honor was confirmed, along with that of the crew and officers. That included George Melville, who was later promoted to engineer in chief, the highest rank an engineer could achieve in the Navy.

After the inquiry, Danenhower continued as a U.S. Navy officer. He married and had a family. But he also continued to battle his mental health disorder, stubbornly believing that he could handle it without medical help. Eventually, he could not. Danenhower killed himself in 1887.

Raymond Newcomb gave up stuffing birds and other wild-life specimens. He spent the rest of his career as the clerk of the board of health in his hometown of Salem, Massachusetts.

Louis Noros delivered mail for the U.S. Postal Service in Fall River, Massachusetts, not far from where Newcomb lived. Noros obviously enjoyed walking, even after his Arctic ordeal.

The Jeannette’s answer to Hercules, William Nindemann made one more trip to the Arctic, then worked for a company that built submarines. As De Long had recommended in his logbook, Nindemann received the Congressional Medal of Honor for working tirelessly to mend the ship and keep it afloat.

When the Jeannette finally did sink, Aneguin helped his shipmates stay alive with his expert hunting skills. He survived the harrowing journey through the Arctic and into Siberia with Melville. But two months after his group made it safely to a Siberian village, Aneguin died of smallpox. Aneguin and Alexey—another hero of the expedition—were honored with special Congressional medals.

Emma De Long made good on her promise and published her husband’s journals. She also wrote a best-selling memoir, Explorer’s Wife, which lovingly describes her time with De Long and provides great insight into his character. She also made sure that her husband’s remains were brought back from Siberia, in 1884. Emma never remarried and lived to be ninety. She’s buried next to her husband in Woodlawn Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Although De Long worried that the Jeannette’s scientific contributions had gone down with the ship, he must have carried a glimmer of hope that they’d accomplished some -thing. Why else would he have lugged those large, heavy logbooks over hundreds of miles of ice?

De Long’s detailed observations of weather, temperature, astronomy, ocean depths, animals and plants, and the westward drift of the ice pack revealed just how much the Jeannette expedition did accomplish. They’d also disproved faulty information about the Arctic, including the idea of an open polar sea. And De Long and his crew discovered three new islands (Jeannette, Henrietta, and Bennett), claiming them for the United States.

Three years after the Jeannette sank, Inuit fishermen spotted a large ice floe littered with objects off the southern coast of Greenland. They retrieved what they could, including a tent and a pair of sealskin trousers labeled LOUIS NOROS. The articles—abandoned by De Long and his crew after the ship was crushed by ice—had drifted 4,500 miles to the opposite side of the Arctic Ocean.

Explorers build on others’ success and failures, and so Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen was more interested in how far the ice floe had drifted than the articles it carried. Nansen figured that the floe had reached the North Pole on its westerly drift before reaching Greenland. That convinced Nansen that the way to navigate to the pole was to become locked in ice and drift to it.

Nansen had a wooden schooner built, called the Fram, with a thick, rounded hull that wouldn’t be crushed by ice. In 1895, he nearly reached the North Pole by following the same route as the Jeannette and inched closer than De Long or any explorer before him. Nansen and his crew survived the three-year trek and returned home as heroes. But they hadn’t reached the pole. It wasn’t until 1909 that Robert Peary and Matthew Henson finally did.

One hundred and thirty-one years after the Jeannette sailed out of San Francisco harbor, the logbooks that Captain De Long saved were transcribed by citizen scientists. They’d volunteered for a weather project created by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). With the Arctic climate rapidly transforming (ice is melting at an alarming rate), NOAA scientists realized that data recorded by early Arctic explorers could help determine the rate of climate change. Now climate scientists who log into weather-research sites can find De Long’s ice measurements—some of the oldest on record—along with Newcomb’s bird sightings, key information in the study and history of the polar region.

Ironically, the theory that led to the Jeannette’s demise—that the Arctic held an open polar sea—might someday become a reality because of global warming. Explorers have unwittingly contributed to that warming. But maybe that tide will change. The political climate is the greatest obstacle to fixing the actual climate, and it will take great courage and perseverance for forward-thinking leaders to overcome this and other obstacles. Heroes have stepped up throughout history to accomplish incredible things, just like De Long and his crew.

“If men must die, why not in honorable pursuit of knowledge?” George Melville once said. “Woe, woe, to America when the young blood of our nation has no sacrifice to make for science.”