Getting Started

About Essential Oils and Their Extraction Processes

Essential oils hold the life force and vibrational energy of the plants from which they came. As alchemists themselves, plants transform sunlight for many purposes, one of which is to make essential oils.12 These oils are produced for various functions such as aiding growth, attracting insects for pollination, and protecting against fungi or bacteria. Most plants produce essential oils in small quantities, but it is the plants commonly called “aromatics” that create enough for us to harvest and enjoy. Essential oils are obtained from various parts of plants, and depending on the plant, it may produce separate oils from different parts. For example, cinnamon yields oil from both its leaves and bark. Essential oils can be obtained from:

• leaves, stems, twigs

• flowers, flower buds

• fruit or the peel

• wood, bark

• resin, oleoresin, gum

• roots, rhizomes, bulbs

• seeds, kernels, nuts

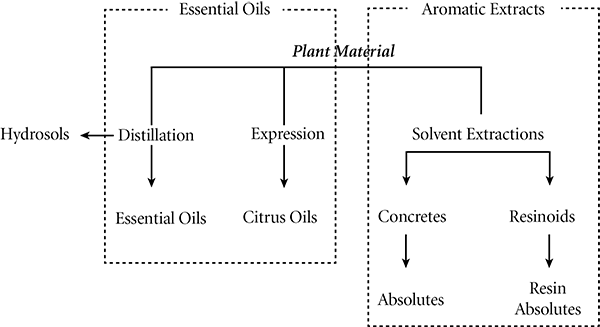

Most of us have an idea of what an essential oil is, but the term is often mistakenly applied to a broad range of aromatic products from almost any natural source. Key aspects to essential oils are that they dissolve in alcohol or oil but not in water, and they evaporate if exposed to the air. Most essential oils are liquid, but some, such as rose oil, may become a semi-solid depending on the temperature. Other oils are solids. However, the defining factor is the method used to extract the oil from plant material. Essential oils, also called volatile oils, are obtained through the processes of distillation and expression. Aromatic extracts are obtained by solvent extraction. The products created by solvent extraction contain both volatile and non-volatile components. Let’s take a closer look at these processes and the products produced from them:

Figure 2.1 Methods of extraction

Figure 2.1 Methods of extraction

The oldest and easiest method of oil extraction is called expression or cold-pressing. Cold-pressed may be a familiar term for those who enjoy cooking with olive oil. For essential oils, this extraction process works only with citrus fruits because they hold high quantities of oil near the surface of their rinds. Depending on the plant, the whole fruit or just the peel is crushed, and then the volatile oil is separated out with a centrifuge. This simple mechanical method does not require heat or chemicals. Just a point to keep in mind: if the plants were not organically grown, there may be a chance that the fruit was sprayed and any pesticide residue that remained on it may result in trace amounts in the oil.

The most prevalent process for extracting essential oils is through distillation, which can be accomplished using steam or water. In the distillation process, the volatile and water-insoluble parts of plants are separated, allowing the essential oil to be collected. Sometimes products are distilled a second time to purify the oil further and rid it of any non-volatile material that may have been left behind the first time.

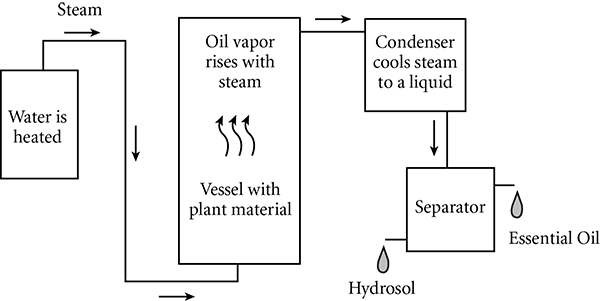

Figure 2.2 The distillation process using steam

Figure 2.2 The distillation process using steam

When steam is used in the distillation process as illustrated in figure 2.2, it is pumped into a vessel from underneath the plant material. Heat and pressure within the vessel produced by the steam cause the plant material to break down and release its volatile oil. The oil becomes vaporized and is transported with the steam through the still into the condenser where they are cooled. This returns the oil and water to their liquid states. Depending on the density of the oil, it will either float to the top or sink to the bottom of the water. Either way, it is easily separated out. Different plants as well as various parts of plants require different amounts of time and temperatures for this process.

Hydro-diffusion is a slightly different form of steam distillation in which the steam is forced into the vessel from above rather than below the plant material. The advantages are that it takes less steam and generally a shorter amount of time for this process. In addition, some perfumers believe that hydro-diffusion produces a richer aroma than the standard steam distillation.

In water distillation, plant material is completely immersed in hot water. This process uses less pressure and slightly lower temperatures than steam distillation. Nevertheless, some plants, such as clary sage and lavender, tend to break down in this process. On the other hand, because neroli (orange blossom) is sensitive to high temperatures, water distillation works well.

After the essential oil is separated from the water in these distillation processes, the water itself is an aromatic byproduct called a hydrosol. Traditionally these have been called floral waters (i.e., rosewater) and contain the water-soluble molecules of aromatic plants. Hydrosols are also called hydroflorates and hydrolats. The latter name ultimately comes from the Latin lac, meaning “milk.” It was so named because floral waters appear somewhat cloudy or milky just after they are separated from the essential oil. Although they are chemically different from their corresponding essential oils, the fragrance is similar. However, because hydrosols are water-based, they do not mix well with oils. Also note that hydrosols should not be used in place of flower-essence remedies as they are not prepared under the same conditions required for consumable products.

The term flower essences may cause some confusion because they are not fragrant and they are not essential oils. They are infusions of flowers in water, which is then mixed in a 50% brandy solution. Whereas the brandy acts as a preservative for flower essences, hydrosols, being mostly water, can go bad.

The heat employed in steam and water distillation can cause changes to the plant material and the resulting oil. Sometimes, this can be a good thing, but in other circumstances, not so much. For example, heat converts the chemical matricin in German chamomile to chamazulene, which gives the oil its blue color. Medicinally, this is considered advantageous because the chamazulene makes the oil useful for anti-inflammatory treatments. On the other hand, jasmine flowers are so delicate that heat or water destroys the volatile oil.

To avoid the negative effects that heat or water have on some plants, the solvent extraction process is used to obtain essential oil. Chemicals such as butane, hexane, ethanol, methanol, or petroleum ether are used in this process to rinse the volatile oil from the plant. This rinsing produces a semi-solid, waxy product called a concrete, which, in addition to the volatile oil, contains the plant’s waxes and fatty acids. In the case of jasmine, the concrete is 50% wax and 50% volatile oil. An advantage of a concrete is that it is more stable and concentrated than an essential oil.

Further rinsing with alcohol or ethanol, or a freezing process is used to remove the solvents and waxes. This step produces a substance called an absolute. While these substances are usually viscous liquids, they can be solids or semi-solids. Absolutes are highly concentrated and have a stronger, richer fragrance that is often more like the plant itself than the essential oil, which makes them attractive for perfumery. The solvent extraction method produces a greater yield than distillation and is useful on plants that generally have low quantities of oil. Absolutes and concretes are sometimes distilled to produce an essential oil. A problem with absolutes and concretes is that they contain impurities: traces of the chemicals used to remove the oil from the plant material.

In an attempt to avoid the problem of impurities, a newer method called CO2 extraction, sometimes called super-critical CO2 extraction, has been developed. This process uses carbon dioxide in a liquid state at high pressure to dissolve plant material and release the oil. Afterwards, when the pressure is reduced, the carbon dioxide returns to its gaseous state, leaving the oil behind and reportedly no chemical residue as in typical solvent extraction. However, like solvent extraction, CO2 extracts contain fats, waxes, and resins from the plants.

There are two types of CO2 extraction products that you may encounter. One is created at lower pressure and designated as a select extract, or SE. It has a liquid consistency and does not contain as much of the plant fat, waxes, and resins. The other type is called a total extract. It is thicker than the select and contains more of the non-soluble plant material. According to Ingrid Martin, author and instructor of aromatherapy at Ashmead College in Seattle, lab tests show “significant differences in chemical compositions” between true essential oils and the CO2 products.13 In addition, I have not found information on experiments to determine if they produce auras as pure essential oils do.

Another substance created by standard solvent extraction is called a resinoid. As the name implies, it comes from resinous plant materials, which include resins, balsams, oleoresins, and oleo gum resins. (Refer to the glossary for information on these substances.) The resinoid end product can be in the form of a viscous liquid, a solid, or a semi-solid. A resin absolute is created by a further extraction process using alcohol. Instead of solvent extraction, a few resins such as frankincense and myrrh are actually steam-distilled to create essential oils.

Another method of extraction is called enfleurage. This is not commonly used today because it is extremely time-consuming and labor intensive, thus making it costly. This process is used to create an absolute from expensive flowers such as jasmine. Instead of extracting the flower essence with a chemical solvent, a fatty substance such as tallow or lard is used. This process involves coating a framed sheet of glass with the fat and then placing a layer of flowers in it. Another frame of glass is placed on top of the flowers, which in turn is coated with fat on which a layer flowers is placed, and so on.

Once a day the whole array of glass frames is disassembled, the flowers picked out, and new ones placed in the same fat and then everything is stacked again. This process goes on until the fat becomes saturated with volatile oil. The number of days it takes depends on the type of flower—for jasmine it takes about 70 days. After the flowers are picked out on the final day, the fat is rinsed with alcohol to separate the oil from it. When the alcohol evaporates, an absolute is left. This type of absolute itself is sometimes called an enfleurage.

Another product you may encounter is called an infused oil; however, this is not an essential oil. An infused oil is created in an easy, low-cost process by soaking plant material in warm vegetable oil to infuse it with a plant’s aroma. A very low amount of essential oil is actually released into the oil. Infusion, also called maceration, is a very old method that was used by the ancient Egyptians to extract fragrance and other plant substances for culinary and medicinal purposes. Infused oil is not a bad thing, and in fact it is quite nice for cooking or using on salads. Rosemary in olive oil is one of my favorites. However, keep in mind that this is not an essential oil and it should not be priced or passed off as one.

There are a few things to watch out for when purchasing essential oils. First, there are the synthetic oils. While these are lower in cost they are also lower in quality because they are created chemically, usually with petroleum byproducts, instead of with plant material. These oils may smell like the real thing, but they do not carry the true essence or synergy of the natural world and will do nothing to boost magical intent. Another thing to be aware of is dilution with a carrier oil. A simple way to test for this is to put a drop of the essential oil on a piece of paper. After it evaporates, there should be no trace left behind; however, an oily mark indicates the presence of a carrier oil.

Pricing can be a red flag indicating adulterated or synthetic oil if a company’s products all cost the same. Some plants are simply more expensive than others, and this is reflected in the price of essential oils. Also, anything labeled “nature-identical” is another red flag that usually indicates that an oil is synthetic or a natural oil has been adulterated with a synthetic version. In my mind, nature means the natural world, period. There is nothing “identical” to it.

A final point to note is that essential oils come from plants and not animals. Musk, civet, and other oils from animals should not be classified as essential oils as they do not contain life-force essence.

Let the Blending Begin

The equipment needed for blending essential oils is fairly minimal. After deciding which essential oils you want to use, purchase them in small amounts, as it does not take much to create blends for magic work. Store the oils in a cool, dark, and dry environment. Avoid keeping them in a bathroom or kitchen as the humidity and fluctuating temperatures of these rooms may damage the oils. Because essential oils are highly concentrated, you will also need a carrier oil (sometimes called a base oil), into which your blends will be mixed. (Refer to chapter 7 for details on carrier oils.) Carrier oils are important because essential oils should never be used on the skin full strength as they may cause irritation. In addition to the essential and carrier oils, other items that you will need include:

• small bottles with screw-on caps for blending and storing essential oils, and for mixing with carrier oils

• small droppers to transfer essential and carrier oils into blending bottles

• a dropper marked with a milliliter gauge for measuring carrier oil (optional)

• small adhesive labels

• a notebook

• cotton swabs or perfume blotter strips/scent testing strips (optional)

All bottles used for essential oils should be dark in color and made of glass. A dark bottle prevents oil degradation caused by light. Most bottles on the market are usually amber or cobalt blue and come in a range of sizes. Never use plastic because the bottle’s chemical composition can interact with essential oils. The 2 and 5 milliliter size bottles are good for blending essential oils, and the 15 or 30 milliliter sizes work well for combining them with carrier oil. Also have a separate dropper for each essential oil when transferring them to the blending bottle to avoid even a minor inadvertent mixing of oils. Even a tiny bit of different oil can change the fragrance. Make sure that the bottles and droppers are clean and dry before use. It is best to work on a surface that is washable because essential oils can damage varnish, paint, and plastic surfaces. I also recommend putting down a layer of paper towels to catch any stray drops.

For the moment we will assume that you have chosen your essential and carrier oils and you have all of your paraphernalia in front of you. Now what?

Because these oil blends are going to be used for magic and ritual, I like to set that intent from the very beginning. After I assemble all my blending gear, I draw a pentagram with a felt-tip pen on the paper towels on my work surface. While I’m doing this, I like to chant or say an incantation such as:

Green world, green world, abundant and pure;

Bring forth your strength, beauty, and more.

Green world, green world please assist me;

Manifest my intentions, so mote it be.

For your first blend it’s a good idea to start with three oils, so it will be interesting but simple. In fact, more is not always better, and some really nice blends can be made with two to four oils. The first step is to get familiar with the individual scents. Open one bottle of essential oil and dip a cotton swab or blotter strip into the oil. Gently waft it back and forth under your nose. If you are not using a swab or strips, waft the bottle back and forth but hold it farther than you would the blotter strip (no closer than your chin), as the fragrance directly from the bottle will be stronger.

Close your eyes for a moment and allow the scent to speak to you. Does it evoke any particular sensation, emotion, or image? Take a moment to write your impressions in your notebook and then put the lid back on the bottle or set the swab/blotter strip aside. You may also want to walk into a different room to clear your senses of the fragrance before moving on to the next oil. Although I have not tried it, I have heard that wafting fresh coffee grounds under the nose can clear the olfactory senses.

When you return to your workspace, repeat this process for the other oils. The last step before actually mixing them is to take all three swabs or blotter strips and waft them together under your nose. If you are not using these, set all three open bottles together and move your face back and forth above them. This will provide a little preview of how the oils may blend, but don’t jump to any conclusions. You will only know how the blend works after the oils are actually mixed and they have time to settle and mature.

Now, you are ready to blend. Using separate droppers, put one drop of each essential oil into the blending bottle. While Agent 007 may have preferred his martini “shaken, not stirred,” for mixing oils we want to swirl, not shake. For most blends, swirl in a deosil direction; however, when blending for banishing, protection, or some other intentions, you may want to swirl the opposite way in a widdershins direction. After a few swirls, waft the bottle near your face to preview the blend. Keep in mind the strength of the oils’ initial intensity, which is important so one doesn’t overpower the others. If all three oils are rated at the same strength, it’s not a problem, but chances are they may be different. If one oil is stronger than the other two, add a drop more of the others. If they are all different strengths, adjust the amounts accordingly. Before taking another whiff, set the bottle aside, walk around the room or into the next room for a few minutes before returning to take a whiff.

As with most things related to blending oils, there are different scales for rating the initial strength of oils. I find a simple 1 to 5 works well for me, and it is the one that I have used throughout this book.

|

Table 2.1 Initial Strength of Essential Oil Aroma |

|

1 = light 2 = mild 3 = medium 4 = strong 5 = very strong |

At this point the blend is in its infancy. Take notes about how many drops of each oil you used as well as your initial impression of the mixture. Don’t be afraid to make corrections. If your intuition tells you that a drop more of an oil would be better, try it. This is the way to learn and hone your skills. However, if the mix seems as though it’s almost right or if you are not sure about it, refrain from adding more. Instead, put the lid on the bottle, wash the droppers, and let the blend settle for a couple of hours before taking another whiff. Unless you are really unhappy with the blend at that point, don’t tinker; instead, take notes about any differences you may detect.

Give the blend about two days before doing another whiff test. Again, refrain from making adjustments and let the green world work its magic. Now comes the hard part of waiting at least a week or more to give the blend time to mature. It takes time for the chemistry of the oils to change and develop, as some molecules will break up and re-form new ones with the other oils. You may be surprised to find that something you thought needed a tweak has turned into an aromatic jewel.

Taking notes at each step and after each whiff test is important, so that when you find the right mix you can duplicate it as well as increase the amount. And on occasion (the author speaks from experience) you may not want to repeat it. It happens and that’s how we learn, although understanding the selection methods increases your chances of producing a winner. I also recommend labeling the bottle with the date and giving it a name such as banishing oil or love potion or simply listing the ingredients. Of course, you can also be creative with the names.

Keep the bottle tightly closed, in a cool place away from light. When stored this way, essential oils can remain potent for many years. Also, be sure to keep them out of reach of children.

After your aromatic creation has had a week or so to mature, it can be added to a carrier oil and then used. Be sure to use separate droppers for the carrier and the essential-oil blend. As noted in the list of equipment, you might want to purchase a dropper with a milliliter gauge to make measuring the carrier oil easier. These can be found in most pharmacies. Table 2.2 is a measurement conversion chart that includes ounces and teaspoons and it is intended for comparative purposes.

|

Table 2.2 Measurement Conversion Chart |

|

20–24 drops= 1 ml= ¼ teaspoon |

|

40–48 drops= 2 ml= ½ teaspoon |

|

100 drops= 5 ml= 1 teaspoon= ¹⁄₆ oz |

|

200 drops= 10 ml= 2 teaspoons= ⅓ oz |

|

300 drops= 15 ml= 1 tablespoon= ½ oz |

|

600 drops= 30 ml= 2 tablespoons= 1 ounce |

Since we are blending very small amounts for magic work, it is easier to think and measure in milliliters for carrier oil and drops for essential oil. Because of the potent energy of essential oils—and magic is all about energy—only small amounts are needed. Also, keep in mind that these measurements are approximate, since drop sizes vary, especially with thicker oils. This is why I stress the importance of keeping good notes.

|

Table 2.3 Dilution Ratio Guide |

|||||

|

Carrier Oil |

5 ml |

10 ml |

15 ml |

30 ml |

Ratio |

|

Essential oil |

1–2 drops |

2–3 drops |

3–5 drops |

6–10 drops |

1% |

|

Essential oil |

2–3 drops |

4–7 drops |

6–10 drops |

12–20 drops |

2% |

|

Essential oil |

3–5 drops |

6–10 drops |

9–16 drops |

18–32 drops |

3% |

|

Essential oil |

4–7 drops |

8–14 drops |

12–20 drops |

24–40 drops |

4% |

Begin mixing your essential and carrier oils at a 2% dilution by putting 10 ml (milliliters) of carrier oil in a clean bottle and then adding 4 drops of your blend. Take another clean bottle and try a 3% dilution with 10 ml of carrier oil and 6 drops of your blend. Take a whiff of each dilution and then take notes. Experiment with varying amounts and dilution ratios and keep in mind the specific use of the oil, especially if it is to be used on the body.

|

Table 2.4 Quick Guide for Dilution Ratios in 10 ml of Carrier Oil |

||||||

|

Ratio |

.5% |

1% |

1.5% |

2% |

2.5% |

3% |

|

Essential oil |

1 drop |

2 drops |

3 drops |

4 drops |

5 drops |

6 drops |

Hydrosols can also be blended together, but unlike essential oils they do not require a carrier oil. Simply mix and they are ready to go. Because they are less concentrated than essential oils and less expensive, it’s common to work in larger quantities measuring them in milliliters instead of drops. As with the oils, use separate droppers to avoid inadvertent mixing. Hydrosols are water based and must be kept in airtight bottles to prevent airborne contamination just like any type of water. Even when stored in the fridge, if they don’t look or smell good and fresh, throw them away.

Here’s an easy way to make your own flower water with a single oil or a blend: Put 100 ml (about 3½ ounces) of spring water in a bottle and then add 20 to 30 drops of

essential oil. Give it a few days before using. Even though the essential oil won’t dissolve, it will impart fragrance to the water.

Once you have created several blends, you might want to start a recipe box just like the good old-fashioned ones for kitchen recipes. Refer back to your notes and then write out a card for each blend. You could also create blend charts on your computer and print them out. Include the name of your blend and perhaps the date you created it, the amount of and type of carrier oil you used, and then list each essential oil and the number of drops for each. Over time you will find that this not only saves you time, but it will also become a source of inspiration when you are thinking of creating another blend.

Before moving on, I want to explain my notations. In some cases, more than one oil is produced from a plant. For example, oil is extracted from the bark of cinnamon trees as well as its leaves. Where it is important to make a distinction, I have noted “cinnamon (bark oil)” or “cinnamon (leaf oil).” Otherwise, the word cinnamon on its own refers to both oils. The same is true for other oils where more than one species, such as chamomile, is represented in this book. When a specific one is referenced, it is noted as “chamomile (German)” or “chamomile (Roman).” Where a reference is made to both, just the word chamomile will appear.

Safety Guidelines

Before starting our in-depth study of blending methods, let’s talk about safety. Essential oils, like plants, may be dangerous and harmful if used improperly. This is why it is important to store them out of reach of children. Pregnant women should take extra care, and read and heed warning information. Avoid rubbing your eyes or handling your contact lenses if you have oil on your fingers, as some oils may irritate eyes and damage contacts. If you get essential oil in your eye, flush it with cold milk to dilute the oil. As previously mentioned, the fatty lipids in milk act the same as carrier oils. Since essential oils are not water-soluble, water would only spread the oil around. Also, avoid getting oil vapors in your eyes, as that can also cause irritation.

Also as previously mentioned, do not add essential oils directly to bath water as they can irritate the skin. This can happen because essential oils will float, undiluted, on top of the water. Essential oils should not be taken internally without the advice of a physician or trained health care provider.

As I have stressed, essential oils must be diluted before use. This is especially true for use on the body, with lavender being the only exception. Sandalwood and ylang-ylang are considered very gentle and often used neat for perfume; however, it is important to do a patch test on the skin first and check any other warning information before doing so. To do a patch test, put a couple of drops of essential oil on your wrist and then cover it loosely with an adhesive bandage. After a couple of hours, remove the bandage and check for any redness or signs of irritation. If these occur, rinse the area with cold milk. You may try the test again at another time or on the other wrist with the essential oil diluted in a carrier oil. If you have sensitive skin, it is advisable to do a patch test with all diluted oils, especially for those listed in the safety guidelines section below. Hydrosols should not be used in place of flower-essence remedies, as they are not processed or prepared for internal use.

The following table lists the general warnings and safety issues of some essential oils. While there are exceptions and each person may react differently to various oils, it is best to err on the side of caution. Read manufacturers’ labels, and when in doubt, don’t use a particular oil. People with epilepsy or other seizure disorders and those with high blood pressure should consult their doctors before using essential oils. You may also want to consult your pediatrician before using essential oils on children.

|

Table 2.5 Safety Guidelines |

|

|

Dermal/Skin Irritation—These oils may cause irritation to the skin, especially if used in high concentrations |

allspice, anise, basil, birch, cajeput, caraway, cedarwood, chamomile, cinnamon, citronella, clove, eucalyptus, ginger, juniper, lemon, lemon balm, lemongrass, orange, parsley, pepper, peppermint, pine, tagetes, thyme, turmeric |

|

Diabetes—Avoid use of this oil |

angelica |

|

Epilepsy or Seizure Disorders—These oils should be avoided |

basil, camphor, fennel, hyssop, lavender (spike), rosemary, sage (common) |

|

Hazardous—These oils should not be used on the skin |

cassia, cinnamon (bark oil), fennel (bitter), mugwort, oregano, sage (common), savory |

|

High Blood Pressure—Avoid these oils |

hyssop, peppermint, pine, rosemary, sage (common), thyme |

|

Homeopathy—These oils should not be used when undergoing homeopathic treatment |

camphor, eucalyptus, pepper, peppermint |

|

Table 2.5 Safety Guidelines (continued) |

|

|

Moderation—Use these oils in moderation |

anise, basil, bay, camphor, cedarwood (Virginia), cinnamon (leaf), clove, coriander, eucalyptus, fennel (sweet), hops, hyssop, juniper, marjoram, nutmeg, parsley, pepper, peppermint, sage (common, Spanish), star anise, tagetes, tarragon, thyme, turmeric, valerian |

|

Orally Toxic |

eucalyptus, mugwort, sage (common), tarragon |

|

Photosensitivity—These oils may cause a rash or dark pigmentation on skin exposed to sunlight within a few days after application |

angelica (root oil), bergamot, cumin, ginger, lemon, lime, lovage, mandarin, orange (bitter) |

|

Pregnancy—The following oils should be avoided during pregnancy |

angelica, anise, basil, bay, camphor, cassia, cedarwood, celery, cinnamon, citronella, clary sage, clove, cumin, fennel, hyssop, juniper, labdanum, lovage, marjoram, myrrh, nutmeg, oregano, parsley, peppermint, rose, rosemary, snakeroot, sage (Spanish), savory, star anise, tarragon, thyme, turmeric Abortifacient: mugwort, sage (common) |

|

Sensitization—In addition to the listing for dermal/skin irritation, these oils may cause irritation for people with sensitive skin |

bay, benzoin, cananga, celery, fennel, geranium, ginger, hops, jasmine, lemon balm, litsea, lovage, storax, tea tree, thyme, turmeric, valerian, yarrow, ylang-ylang |

Sample Blend

This is an example of blending by botanical family. Members of the citrus family work so well together that it’s hard to go wrong with them.

Prosperity and Well-Being Blend

Sweet orange: 12 drops

Grapefruit: 12 drops

Mandarin: 11 drops

Bergamot: 7 drops

Lemon: 4 drops

I like to use this blend as a house blessing, and since I usually have a seasonal wreath on the front door, that is where I place it. All five oils are associated with well-being and strength. Grapefruit, lemon, and orange are associated with abundance, and bergamot and mandarin with prosperity. I also like to use this blend indoors with a tealight diffuser, especially during the winter, to freshen the house and get energy moving. Bergamot, grapefruit, lemon, and orange are associated with energy and mandarin with happiness.

Now that you know how to mix oils and have had a sneak peek at a botanical family blend, let’s move on and explore this method first.