12

Is It September Yet?

I think the hardest thing for any player is to say no more.

—Lee Mazzilli

- Days 28–32

- July 16–20, 2015

- Miles driven: 6,892

- Cups of coffee: 76

- Jacksonville FL to New York NY

When I left Oakland a month ago, I had no idea how important father figures would be to this story. Of the nine Wax Packers I’ve covered so far, only three had fathers who were reliable, positive influences in their lives (Rance, Tempy, and Jaime); the other six dads ranged from alcoholics to virtual strangers, with plenty of neglect and abuse in between. As I leave the stickiness of Florida in my rearview mirror, I head up the East Coast in pursuit of the next Wax Packer, Lee Mazzilli, and a visit with my own father.

My dad took me to countless ball games as a kid. My memories of those times are a collage of senses—the smell of sausage, peppers, and onions from a vendor outside Fenway Park, a sandwich my dad had to have before every game; his hairy legs outstretched next to me in the bleachers; the steady calm of his voice as he explained how to score a game. Whatever we lacked in common ground or understanding, we made up for with baseball.

10. Lee Mazzilli

He showed me how to wrap tin foil around the antenna of my transistor radio to get the Phillies radio station at night when the signal seemed magically stronger. He threw Wiffle Balls to me in the backyard until his arm felt like rubber. He came to every single Little League game I played and always, always told me how proud he was of me.

I idolized him. He was Google before the internet, his broad interests and voracious literary diet providing answers to any question I asked. And I delighted in the unwavering simplicity with which he explained the world to me.

“Who are the good guys and the bad guys?” I would ask when Tom Brokaw came on the TV to give an update on President Reagan’s latest talks with Mikhail Gorbachev.

“The Russians are bad and we’re good,” he would say, rubbing his bushy black mustache. I became a little Republican, even dressing up one year as George H. W. Bush for Halloween. I sometimes miss that world, a clearly defined place of heroes and villains where my dad made everything feel safe and secure.

I imprinted on the outwardly perfect example that he and my mom set of their marriage, and I assumed that I too would grow up to meet a nice girl in college and have a family that went to church on Sundays. But as I grew into adulthood, developing my own set of beliefs and values and learning to think for myself, I had to deal with the challenges that we all face once the playing field is level with that of our parents. I began to see serious cracks in their marriage, the way that it was too traditional, too asymmetrical; they were stuck in the old-fashioned spheres of wife as homemaker and husband as breadwinner. My mom knew nothing of their finances, and while my dad was fair-minded and kind, he controlled all the purse strings. They grew apart, finding other partners for emotional support, and although my dad ultimately was the one who wanted a divorce, the foundation of their marriage had long since crumbled. The asymmetry of their marriage made the split harder on my mom, who suddenly found herself a fifty-eight-year-old single woman who hadn’t been in the workforce in thirty years and had never paid her own bills.

The divorce, coupled with the demise of my relationship with Kay, left me hurt and angry. I had been a model teenager who had never given my parents any trouble, but in my twenties I lashed out at both of them for having built up an example that did not endure. But as Don Carman told me, when you’re angry you’re really just feeling sorry for yourself.

My mom now lives near me in California, thrilled to be a grandmother (my sister’s two kids have taken the pressure off me to reproduce). My dad remarried and moved to Chicago, but I’ve struggled to acclimate to our new dynamic as adults. Our conversations, mostly done via phone these days, orbit around some emotional sphere, occasionally scratching the surface but never blasting into its core. We discuss business and politics and movies but rarely venture into the intensely personal territory where I like to be. When he asks about my life, which he always makes a point of doing, I hear myself parroting back to him, talking about everything except what really matters. I think I do this out of some deep-seated respect for the boundaries of our old relationship, because I still want to be the ten-year-old who thinks the Soviets are evil and the Americans are good and who idolizes his dad, not someone who makes him feel uncomfortable.

When I see him in a few short hours, I know we’ll talk baseball. But this time, when he asks about my life, I want to blast into that emotional sphere, to honestly answer that most basic of questions: What’s new? I want to tell him who I really am—a thirty-four-year-old liberal with Buddhist leanings who might not want to follow the seemingly preordained path of marriage and kids and who thinks Reagan wasn’t that great a president after all. And I don’t want his approval or even a response. I just want him to listen.

June 5, 1973

Back behind the baseball field of Abraham Lincoln High, or rather the patch of dirt and weeds masquerading as a baseball field, Lee Mazzilli is hiding with his buddies. Although school isn’t quite out yet, summer is here, and Maz can’t be happier. The country may be in turmoil, haunted by Vietnam and the looming specter of Watergate, but for Maz, summer means nonstop baseball here in the working-class Italian neighborhood of Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, only a couple miles northeast of Coney Island.

Maz is a good student with a bad case of senioritis, seeing no harm in cutting class now and then to enjoy the sunshine, like he’s doing now, sitting under a tree near home plate.

Across the field he sees a figure approaching and within moments recognizes the aggravated march of his baseball coach, Herb Isaacson.

“Shit,” Maz says to his friends. “Coach sees me.”

Isaacson stomps closer, stopping a few feet away and peering hard into Maz’s face, turning Maz’s olive complexion slightly pink.

“Hey, Mazzo, you hear anything?” he asks gruffly.

“What do you mean coach?” Maz musters.

Shit. I’m fucked, he thinks.

The old man’s face breaks into a grin.

“Mets.”

He puts up a single finger.

Once again: “Mets.”

Maz’s eyes grow wide. It finally registers.

He has just been taken in the first round of the Major League Baseball draft (the fourteenth overall pick) by his home team, the New York Mets.

He takes off running. He runs and runs and runs through the cluttered city streets, past local markets and street vendors, straight through blinking orange Don’t Walk signs, dodging cars and smiling at the honks that follow. He doesn’t stop until he reaches East 12th Street between Avenues Y and Z, dashing up to the second floor and bursting through the door of the three-room apartment he shares with his parents and older siblings, Joann and Freddy. It’s a modest dwelling for the second-generation Italian American family, space at such a premium that the bathroom is located outside and down a hallway.

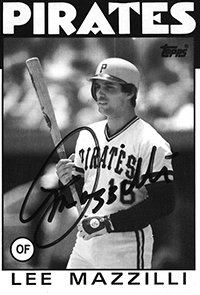

His father, Libero, hears him before he sees him. A welterweight boxer turned piano tuner, he knows nothing about baseball but everything about fatherhood, taking Maz to countless speed-skating practices and competitions in the winter and baseball games in the summer. Years from now, when Maz is an established Major Leaguer, Libero will frame each of his baseball cards as a reminder of his youngest son’s success.

The whole family knows that Maz is going places, knows that he won’t be in Sheepshead Bay long, not with that speed and athleticism. Scouts have been over to the house for his mom June’s famous chicken cacciatore, and multiple teams have shown interest. Maz just wanted to get drafted, let alone in the first round. But first round and taken by his home team? Too good.

“Dad!” he gasps, trying to catch his breath. “Mets! First round!”

His dad rushes forward and squeezes his son, kissing his cheek and telling him how proud he is. They hold each other, tears streaming down their faces.

*

I’ve lived in or near cities all my life, but nothing compares to New York City. After having spent only $8.75 on tolls the entire trip, I drop $35.10 to get across the maze of bridges and expressways guarding the Big Apple. Driving one of the perilously narrow, perpetually-under-construction expressways choked with traffic, I pass old brick apartment building after apartment building stacked close together, dressed with steel fire escapes. I marvel at the mass of humanity contained within a single block, vertical row after row of windows and air-conditioning units. And this isn’t even Manhattan. This is Staten Island.

Maz now lives in Greenwich, Connecticut, in a five-bedroom, four-bathroom Colonial with a large backyard perfect for Wiffle Ball games and Easter egg hunts. The wealthiest town in the state, Greenwich, a haven for hedge funds and private equity firms, is only forty minutes from the heart of Manhattan. This may be where Maz ended up, but it’s not where he started. To trace his roots, my dad and I are staying in a Comfort Inn in Brooklyn’s Sheepshead Bay, spitting distance from Coney Island.

Maz is now a spring training instructor and special advisor for the Yankees, and we’ve made plans to meet tomorrow night in the town of Rye for dinner. With his son, LJ, a prospect in the Mets’ Minor League system, Maz spends much of his time watching him play, and since it’s the heart of the baseball season, that time is limited. Still, I’m grateful that he is willing to set aside a couple hours for a complete stranger with no book contract or baseball writing credentials. After I left a few messages on his home answering machine, Maz had called me back right before the trip, deeply apologetic: “I really apologize. I know you called a couple of times. I’m not normally like that,” he said in a thick Brooklyn accent, leaving me stunned that this ex-ballplayer would think he had anything to apologize to me for. His wife, Dani, a former broadcaster, was also super helpful in arranging our meeting. While I was in Florida a couple days ago, I reached her on the phone. “I’ll help you set it up,” she offered. “Lee’s a private guy; if you want to know where he is at a party, look in the corner of the room,” she said.

I meet up with my dad in our hotel room. I’ve conscripted him to be my research assistant for the next couple days, figuring this trip will serve as our annual father-son road get-together, a tradition that goes back several years.

I walk in the room and give him a big hug.

“Hey, big guy!” he says, his usual greeting for me. “How was the New Jersey Turnpike? Was it jammed?” he asks.

“Not too bad,” I reply.

“I’m so glad I MapQuested my route,” he says about his drive. “I would never have found this place. That MapQuest is pretty good.”

Yes, MapQuest. He’ll discover Google Maps in about 2020.

The British Open golf tournament is on TV (golf is his other favorite sport). “They had to delay the tournament due to high winds,” he says as we sit on our respective beds, facing the tube. He’s almost seventy but could pass for a decade less, his brown hair flecked with gray and cut short. Unlike Rance, his eighties mustache is long gone, and he’s wearing a gray Duke shirt (my alma mater) tucked into dark blue jeans. We fall right back into our old pattern, talking about weather and traffic, circling that emotional sphere. And, of course, our ever-reliable go-to: baseball.

“I was trying to watch the Dodgers-Nationals game last night,” he says, eyes on the TV. “They had to suspend it because the lights went out twice. The Dodgers were winning 3–2.” He pauses, then continues: “I was watching this thing on 20/20 about this kidnapping in Vallejo. That’s kind of near where you live, isn’t it?” I nod, and we move on to a vast range of topics, from the odd shape of the state of Maryland to the paucity of black hockey players to the socioeconomics of Jacksonville. We don’t talk about his relationship with my stepmom, Katina, or my dating life or how my mother is doing out in California. And I’m just as much to blame as he is, too uncomfortable with the thought of making him uncomfortable. I sip my hotel coffee and stare at the screen while we chat, our eyes in parallel.

Given that we have a job to do, I debrief my dad on Lee Mazzilli. Growing up in blue-collar Sheepshead Bay with two working parents, Maz was a natural athlete. He was ambidextrous, giving him the unusual talent of throwing equally well with both arms (although he wasn’t particularly strong from either side—the “weak arm” label followed him throughout his career). When he was ten, he started fatiguing quickly and falling often when competing, and orthopedic surgeon Dr. Arthur Michele diagnosed him with a muscle imbalance caused by an atrophied left hip, affecting his balance. “I came to the conclusion that Lee possessed total physical unfitness,” said Dr. Michele.1 Maz learned an early and important lesson in humility. Accustomed to winning at everything, he suddenly had to undergo painful physical therapy sessions every morning and evening to strengthen his left side, a ritual that would last for eight years. By the time he was twenty-one, he was playing center field for the New York Mets, and a few years later, he was one of the best players in the National League and the sole bright spot on an otherwise pitiful Mets team. This is the Maz whom my dad remembers playing center field in the 1970s, winning the 1979 All-Star Game for the National League with a walk-off walk, of all things, which he accentuated with a spectacular bat flip, decades ahead of his time.

Every newspaper article from that era referred as much to Maz’s good looks as to his baseball prowess; playing in New York meant constant media attention, and his tall, dark, and handsome profile made him a crossover celebrity. He signed a contract with the William Morris Agency, read for TV and movie parts, and was constantly compared to John Travolta; even Frank Sinatra brought him onstage during a show at Caesars Palace. But while the spotlight was flattering, Maz was never comfortable in its glare—he never stopped being the quietly confident, always generous kid from Sheepshead Bay. “I had a very hard time dealing with that [the fame]. I look at myself as just a guy from the streets of New York,” he said.2 When twenty-two-year-old clubhouse assistant Charlie Samuels needed a place to live in 1980, Maz, then a bachelor, invited him to crash at his house on Long Island. “I don’t put myself on a pedestal. I am no better than the man cleaning the ballpark or the woman selling hot dogs. I just happen to be an athlete,” he told the New York Times.3

Maz’s time as baseball royalty was short-lived, however, as injuries slowed him down. He was traded to Texas, then to the Yankees, then to the Pirates within one season. He spent the rest of his career as a role player, albeit an important one, delivering key hits upon his return to the Mets in 1986 in their championship season. He retired following a stint with the Toronto Blue Jays in 1989 at thirty-four, the same age I am now.

*

My dad is not a shy man.

We’re walking the cramped streets of Sheepshead Bay, the worn asphalt baking in the hot summer sun, passing row after row of old brick apartment buildings mixed with delis and small groceries. The diversity of the neighborhood resembles the United Nations chamber and reminds me of my home back in Oakland. We’re outside for only a few minutes, my nose in my notebook, when I hear my dad mumble, “If I see somebody a little bit older . . .” Then I hear his voice: “Excuse me! Are you from this area?”

Here we go, I think, remembering all our family vacations, when my dad would talk to everybody, always super cheerful and positive.

I look up and see him in front of an older woman with dyed red hair wearing a sundress. She’s carrying two plastic bags of groceries.

She stares at him with the compassion of a pitchfork. The look is so hostile, so truculent, that I wonder if I had misheard him. Had he asked what kind of underwear she had on? How much money she makes?

He repeats the question, and her face hardens more. She glares another instant, spins on her heel, and marches off.

“Dad, remember, we’re in New York,” I say.

He just laughs and looks for his next opportunity. We’re now outside a supermarket, where he approaches another older woman, this one pushing a cart. She has bright blue fingernails and is wearing white pants. I stand to the side, half smiling, half cringing.

“Are you from this area?” he asks her.

“Yeah,” she replies curtly. A large nose dominates her narrow face.

“Is this a big Italian area?” he asks.

“Used to be. Now it’s Russians, Muslims, Jews, and some Italians,” she says, all business. “It’s changed a lot.”

“My son here, he’s writing a book on Lee Mazzilli, who grew up around here,” my dad says proudly, motioning toward me. I give a meek smile.

“Oh yeah, his mom used to go to the beauty salon down there,” she replies, her face softening. “I knew of her but didn’t know her personally,” she says. I’m amazed that the Mazzilli name is still known on these streets. I thank her for her time and ask her if there’s any place to get lunch nearby.

“Yeah, Emmons Avenue,” she says, launching into a long set of directions that has me reaching for my phone.

“Are there any places closer?” I ask.

“What’s wrong with you? You’re young, you walked all the way down here!” she says, then pauses and adds, “Go and call a taxi, or an Uber, whatever you kids use,” before waving good-bye and walking away.

“You’re right, we are in New York,” my dad says once she’s gone, cracking us both up.

A few hours later we walk through the turnstiles at MCU Park to watch the Single-A Brooklyn Cyclones take on the Vermont Lake Monsters. This is baseball at its roots, a sleepy game played on a languid summer night in front of a few thousand people with the Thunderbolt rollercoaster visible beyond the left-field fence. Twelve bucks gets us excellent seats down the first-base line, where we sit side by side reading our programs, studying the rosters like homework. It’s hard to tell if the people are here for the game or the nonstop entertainment on the sidelines—it’s YMCA Night, Fireworks Night, Princess and Pirate Night, Honeymooners Night (the TV show), and Bus Operator Sandy Bobblehead Night all in one, the last of which appears to be the Cyclones’ seagull mascot, Sandy, dressed up as the Jackie Gleason Honeymooners character. Between innings, Gong Show–type entertainment distracts the crowd (the PeeWee dance crew! whack an inflatable baseball with a golf club!), and between pitches, the players lining the top step of the dugout peek back to scan the crowd for attractive women, as timeless a baseball tradition as the hot dog. My dad and I trade observations on the game, sprinkling the conversation with politics.

“What do you think of Bernie Sanders for president?” I ask.

“I think he’s a good candidate if you like not having to work for a living,” he says.

“Who do you think the Democratic nominee is going to be?”

“I think it’s going to be Joe Biden,” he says.

Baseball is a game like no other. It’s my favorite for the same reason that it’s many others’ least favorite: it’s long and ponderous. For those prone to boredom, baseball is excruciating; but for those who relish stillness, it is exquisite. Those long lulls, anathema to the always stimulated, provide the ideal setting for building relationships. Baseball is the backdrop for self-discovery.

Somewhere in there, the Lake Monsters beat the Cyclones 4–3, but the final score hardly matters. For three hours I am that ten-year-old in our living room again, and there are good guys (John Kasich, Jeb Bush) and bad guys (Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden). Three hours sitting side by side, and yet I still haven’t worked up the courage to really talk to him.

Maybe tomorrow.

*

I’m sitting across from Maz in the back of Ruby’s Oyster Bar and Bistro in the tony suburb of Rye. My dad sits to my left, and Maz is leaning over a plate of liver, bacon, and onions.

“My wife’s liver is better,” he says in that thick Brooklyn accent.

I now see what all those writers were talking about in the 1970s describing his “matinee idol looks.” Even at sixty, Maz is debonair, his black hair slicked back, his tanned skin glowing from his six-foot-one frame. He’s wearing a snug black T-shirt that conforms to his thick upper arms and chest and a pair of black jeans. As he talks, a tattoo on his left bicep peeks out from under the edge of his sleeve, but not enough for me to identify it.

Maz is an active listener, his dark brown eyes rapt, completely present in the moment. It’s the skill that made him such a good coach and manager once he finished playing. For the first time on the trip, one of the Wax Packers seems as interested in me as I am in him.

“What made you decide to write this book?” he asks.

It’s a simple and obvious question, yet I’m so accustomed to steering the conversation that it throws me a bit.

“As a kid, you know, my first baseball cards were around 1986. I’m thirty-four,” I begin.

“That makes me feel old. I’m probably your dad’s age, right?” he replies.

I explain the premise of the book and my experiences thus far.

“Are you surprised how big leaguers turned out?” he asks, flipping the script some more.

“It ranges a lot. One thing I’ve found interesting is that players aren’t nearly as into baseball as the fans are,” I reply.

“Why is that?” he asks.

I start to respond, and he adds, “I know why, but I want to ask you why.”

“Don Carman considered it self-preservation. What is your take?” I ask.

“Yeah, you know, when we get to a certain age, there are things we can’t do. But in my mind I think I can still do it. I think an athlete always has that competitive edge in him. Always. You never lose that,” he says with the same look that Tempy and Randy had when discussing their desire to get back in the game.

My dad sips his glass of Cabernet Sauvignon, content to take a back seat and listen as Maz and I give and take. He occasionally asks a question or adds a comment but mostly just chuckles at Maz’s dry humor.

“We’re staying in Sheepshead Bay,” I tell him.

“No offense, but that’s not a very good area. I lived there,” he replies. “We had five of us living in a three-room apartment, my brother and sister and my mom and dad. We didn’t have much. But that’s all we knew. It was normal to us,” he says.

“Were you surprised when you got drafted in the first round?” I ask.

“Yeah. Absolutely. I just wanted to get drafted, I didn’t care when. I had no clue where I was going to go,” he says with a smile, flashing a set of bright white teeth.

During his couple of seasons in the Minor Leagues, he got a taste of a world much bigger than Brooklyn. In 1974 he played for the Anderson Mets in western South Carolina.

“When I went down there, you’re down south, and you’re talking the seventies, and it was chain gangs on the side of the road, KKK, all that stuff that I had not been privy to,” he says.

“What was your manager there like, Owen Friend?” I ask.

“Miserable bastard,” he says, cracking up my dad. “I’m gonna be very nice and say that.”

Maz is quick-witted, direct, and honest. He sits with his back against the wall, relaxed and at ease. He tells me about the surreal nature of his relationships with Willie Mays, whom he idolized as a kid and who became his personal mentor during those early years when Maz was learning to play the outfield. We gloss over the highlight of his career, the Mets’ dramatic comeback win over the Red Sox in the 1986 World Series, because what new could possibly be said about one of the most chronicled series in baseball history?

While many of his teammates were careless with their money, living in the moment a little too much, Maz was always smart and careful. He didn’t rush into anything, equally patient at the plate (he excelled at drawing walks) and in his personal life. Enduring yet another question about his love life in a 1980 interview, he said, “It’s tough being married when you play ball. You’re always moving around. I’m not getting married to get divorced. Once I get married, I’ll stay married.”4 A man of his word, Maz married Dani in 1984, and they’re still married today.

I ask how his ride on the baseball carousel came to an end.

“In 1990 there was the lockout. That spring I still wanted to play, but I couldn’t get to camp because of the lockout. And when they finally resolved it, there was a very short window for spring training, so there really wasn’t an opportunity to get invited to spring training to see what you’ve got. And that was it,” he says.

“What did you do that first year you were out?” I ask.

Like the rest of the Wax Packers, his memory of life immediately following retirement is a blur.

“I don’t really know,” he says. “We wanted to start a family [their eldest child, Jenna, was born in 1989]. The stars weren’t lined up right to go back to playing.”

Before long, he was busier than ever, trying on several new careers: he opened a restaurant, went to work with a friend at a mortgage bank, served as commissioner of an independent baseball league, and even starred in an off-Broadway play following a dare from buddy Dan Lauria (the father on The Wonder Years). But no matter what he did, none of it was baseball.

After Maz wandered in the wilderness for six years, Dani brought him home by making him leave home. “My wife, she basically pushed me out the door,” he says, resting his elbow on the chair in front of him.

“Nothing ever fills the void,” Dani said back in 2003, aware that her husband still had baseball left in his system.

“She just knew this was something I needed to do. I needed a push, and she pushed me,” Maz says.

The hardest part was going back on the road, away from his family. Nothing is more important to Maz than family. He eased himself back in, managing the Single-A Tampa Yankees. He and Dani made a pact to never go more than three weeks without getting the family together. By 1999 Maz had graduated to Double-A Norwich, and from 2000 to 2003 he was the first base coach for the New York Yankees, winning another World Series ring in 2000. But he almost didn’t get that far.

His twins, Lacey and LJ, were only seven when he decided to return to the game. LJ in particular was attached to his dad.

“I said to him, ‘Remember in September, Dad’s gonna be home, and I’m gonna take you to soccer and basketball, and I’ll be with you every day,’” he tells me, his dark eyebrows slightly furrowed. I feel my dad shift next to me.

“One day I had an off day and flew home from Florida to surprise my wife,” he begins. “I came home and said, ‘Where’s the big guy?’ She said, ‘He’s in bed.’ I went and surprised him, woke him up. The first thing he said was, ‘Dad, is it September already?’ And that just broke my heart. I went downstairs and told my wife, ‘I can’t do it.’ It killed me,” he says.

We all sit in silence for a moment, staring at our drinks.

“What’s your tattoo about?” I finally ask, breaking the silence.

“That’s me and my brother,” he says, his eyes welling.

He pats his bicep.

“Me and my brother.”

“How would you describe your relationship with your siblings?” I ask. I had read that Maz was the youngest, with Freddy seven and Joann three years older, but I know little else about them.

“I lost my brother,” he says softly. “We were together for fifty-some years, and there wasn’t one time where he and I ever had a fight. Not one time that he and I ever cursed at each other. Never. He was such a big part of my life, losing him—I had a tough time with that,” he says, closing his eyes and reaching his hand to his forehead.

“I lost my best friend,” he adds.

Maz and his wife, Dani, and sister, Joann, helped put together a small charity, the Fred L. Mazzilli Foundation, in his memory to raise money for lung cancer funding.

“It’s just us licking the envelopes and putting the mailings out,” Maz says.

We chat a bit more over coffee, but it’s getting late, and Maz has to get back to Greenwich.

“Thank you for dinner,” he says, gripping my hand tightly and looking me warmly in the eyes. “It’s good to see you’re going out and spending time with your dad. Enjoy your time together—it’s precious.”

My dad and I ride back to Sheepshead Bay together, saying everything by saying nothing at all.

*

The next morning, before parting ways, my dad and I sit at a Starbucks for our other favorite activity: Trivial Pursuit. He’s strong in every category but entertainment, while my weakness is art. For years, although I came close, I could never quite beat him, but the torch has now been passed, as I win handily. He’s got to head back to Chicago, and I’ve got an appointment in Doc Gooden’s living room tomorrow, but I’m not ready to go. I feel that anxious pit in my stomach, that hollow feeling I experienced as my parents drove away after dropping me off for my freshman year of college, effectively ending my childhood.

“Dad,” I begin. He turns his hazel eyes on me, bright but with slight circles underneath. They are the same eyes I have been looking into for thirty-four years. He raises his eyebrows.

“Dad, I want to tell you some things,” I begin. “And I just want you to listen. You can respond if you want to, but mostly I just want you to listen. I don’t need your approval or your opinion, I just want you to know certain things about me.”

“Sure,” he says, crossing his legs, folding his hands, leaning back the same way Maz did last night at the restaurant.

Once I start talking, I don’t even pause to breathe. “I know you want me to find someone special and get married and have kids. I know you think I would be unhappy if I never did that, that my life would somehow be incomplete. You don’t say that out loud, but I know you, I know how you feel. And maybe you’re right, maybe I would be miserable if I was always alone. But I like my life. I’m happy being alone. I like my freedom. I’m not like you, I don’t see the world through the same lens that you do. And I love you so much, you know that, and I am always so grateful for all the opportunities you and Mom gave me. But I’m different from you. I’m not a Christian. I don’t believe in the same God that you do. I like to sit still and meditate and just observe my thoughts. My god is just trying to be as present as I can, which I think is what love really is, and being compassionate to other people, treating them well. I’m telling you all this because I want you to know that me having these beliefs and feeling this way is not out of some defiance of you, it’s not some rejection born out of bitterness about what happened between you and Mom, because I accept all of that. I respect you and love you for who you are, but it’s different from who I am. I need you to know that.”

I ramble. I don’t care. The whole time I look him right in the eye, feeling naked and vulnerable and exposed. When I finish talking, my whole body feels like an unclenched fist, tingling slightly. He looks at me with a look that only a parent can show to a child. After sitting and listening for several minutes, he opens his mouth to reply. “Brad, I know all that,” he says, astonishing me. “And I’m so proud of who you are.”

The world does have good guys and bad guys after all. Heroes do exist. And although he never had his own baseball card, my dad will always be one of them.