7

Operation Barbarossa and the Onset of the Holocaust, June–December 1941

Jürgen Matthäus

On June 22, 1941, the first day of Operation Barbarossa, German army units swept across the border into the Soviet Union. Within a few months the Wehrmacht had conquered a vast strip of land that extended from the Baltic Sea in the north via Belorussia to the southeastern Ukraine. Unlike previous campaigns, this Blitzkrieg did not proceed according to plan. Despite defeats in many battles and an immense loss of men and material, the Red Army was able to stop the German advance, forcing the Wehrmacht into a winter campaign for which it was not prepared. What followed might appear in hindsight as a protracted German retreat that ended in unconditional surrender. In late 1941, however, the extended front line in the east not only demonstrated the Reich’s unbroken military power; it meant suffering and death for millions of people in the occupied parts of the Soviet Union.1

From the beginning, Germany adopted a policy of terror that, though foreshadowed in earlier plans for this war of destruction, gathered momentum over time. Already by the end of 1941, the death toll among noncombatants was devastating. Between 500,000 and 800,000 Jews, including women and children, had been murdered—on average 2,700 to 4,200 per day—and entire regions were reported “free of Jews.” While many Jewish communities, especially in rural areas, were targeted later, the murder of Soviet POWS reached its climax in this early period. In the fall of 1941, Red Army soldiers were dying in German camps at a rate of 6,000 per day; by the spring of 1942, more than 2 million of the 3.5 million Soviet soldiers captured by the Wehrmacht had perished. By the time of their final withdrawal in 1943/44, the Germans had devastated most of the occupied territory, burned thousands of villages, and depopulated vast areas. Reliable estimates on total Soviet losses are difficult to arrive at; a figure of at least 20 million people seems likely.2

In looking for answers to the questions how, when, and why the Nazi persecution of the Jews evolved into the Final Solution, the importance of the war against the Soviet Union can hardly be overestimated. Ever since Operation Barbarossa became an object of research, it has been stressed that the murder of the Jews in the Soviet Union marks a watershed in history, a quantum leap toward the Holocaust.3 Still, despite new research based on sources from east European archives, historians continue to struggle with key questions: What turned men from a variety of groups—Wehrmacht, SS, German police and civil agencies, allied troops, local collaborators—into perpetrators, and how did they interact in the course of this “realization of the unthinkable”?4 How important were orders, guidelines, and instructions issued by Berlin central agencies compared with factors at the local and regional level? What were the driving forces of this process and what were their origins? In addressing these questions, historians have to confront the inappropriateness of monocausal and linear explanations as well as the impossibility of comprehensive understanding. In looking for reasons how, when, and why the “Final Solution” came about, this chapter focuses on developments that were especially relevant for Germany’s crossing the threshold from instances of physical abuse and murder to systematic extermination.

GERMAN PERCEPTIONS AND EXPECTATIONS REGARDING “THE EAST”

Ideological bias influenced more than just the strategic grand designs and military orders drawn up by the top leadership in preparation for the war against the Soviet Union. When Wehrmacht soldiers, SS men, and other Germans crossed the border toward the east, they brought with them more or less fixed images of the region and the people they would encounter. Combining collective stereotypes established in the 19th century with Nazi propaganda slogans and political interests that found expression in the “Barbarossa orders,” these predominantly negative images determined how reality was perceived. Both “endless vastness” and “living space,” “the east” implied a threat to the present as well as a promise for the future. In its origin and function “the east” was also closely associated with other ideological concepts—most notably “the Jew” and “Bolshevism.” Hitler’s ideas regarding “living space” or Lebensraum in the east, hardly original and with strong utopian elements, were well known through his own writings and speeches and those of his closest followers.5 It is much more difficult to gauge the mind-set of Germans outside the narrow, Berlin-based circle of Nazi leaders. Despite their fragmentation along social, organizational, and other lines, the representatives of the occupying power—military officers, soldiers, administrators, policemen—shared perceptions and expectations that formed the background to German policy in the Soviet Union.6

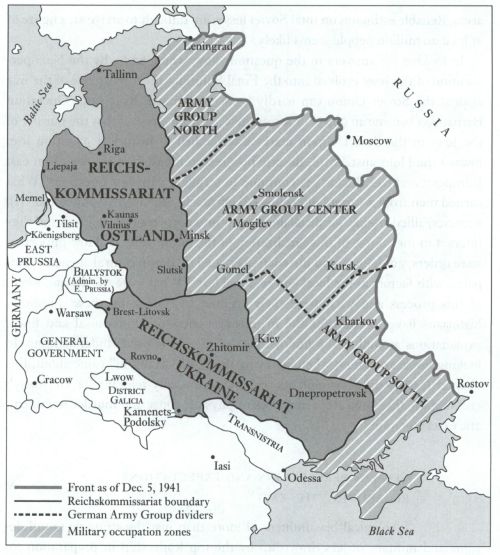

3. OCCUPIED SOVIET TERRITORY, DECEMBER 1941

Images of “the east” had influenced German policy making since World War I, when the German army first occupied parts of the Russian empire. This element of continuity is most obvious when looking at the attitudes toward Russia of commanding Wehrmacht officers, the majority of whom had served during the Great War. Afterward, military conflict between the two countries was perceived as being deeply rooted in history, a struggle in which Germanic peoples fought Slavs for “the defense of European culture against the Muscovite-Asiatic deluge.” The occupation of eastern Poland, parts of the Baltic area, Belorussia, and Ukraine during World War I had also confronted German soldiers with the peoples of eastern Europe. Members of the officer corps in particular regarded the local population not only as different but as degraded and unable to appreciate western values. On the sliding scale of backwardness, the lowest place was reserved for the eastern Jews. Urban ghettos appeared to German soldiers as remnants of medieval times, their occupants filthy and repulsive.7

During World War I, the German army had been unable to secure the captured areas. The threat by franc-tireurs (irregulars) in the west seemed small compared to the danger posed by “bandits” and later communist infiltrators in the east.8 For many officers more than twenty years later, the lessons of the Great War loomed large. In mid-June 1941 the Army High Command’s (Oberkommando des Heeres, OKH) legal expert Lt. General Müller told officers of Panzer Group 3 that the expected severity of the coming war called for equally severe punitive measures against civilian saboteurs. To prove his point, he reminded his audience of the brief Russian occupation of Gumbinnen in Eastern Prussia in 1914 when all inhabitants of villages along the route from Tilsit to Insterburg were threatened with execution if the railway line was damaged. It did not matter that the threat was not executed. “In cases of doubt regarding the perpetrator,” the general advised for the future, “suspicion frequently will have to suffice.” (In Zweifelsfragen über Täterschaft wird häufig der Verdacht genügen müssen.)9

Another crucial element of ideological continuity after 1918—the identification of Jews with Bolshevism—linked old anti-Semitic stereotypes with the new fear of a communist world revolution. Right-wing ideologues and Nazi propagandists like Alfred Rosenberg and Joseph Goebbels tried to paint communism as an aberration from European history, an Asiatic phenomenon alien to all accepted moral categories of the West.10 Affinity to these notions explains to some extent why, compared with the loyalty displayed toward the Nazi state well into its final hours, German military officers had few problems disregarding their oath to protect the democratic system of the Weimar Republic. Hitler’s movement offered promises to all strata of the nationalist elite but had special appeal for the military, since it called for more than a revision of Versailles and offered a chance for rapid remilitarization. Early indications of the army’s eagerness to support the Nazi regime include acquiescence to the murder of political opponents, among them former chancellor and army general Kurt von Schleicher during the so-called Röhm Putsch in late June/early July 1934; and the military’s attitude toward Jews. Not waiting until the Nuremberg laws, the army was quick to enact its own anti-Jewish measures, which excluded Jews from military service and prohibited officers from being married to “non-Aryans.”11

Staff officers of bourgeois upbringing might have resented “Stürmer”-style slogans and the actions of Nazi thugs, but they had no sympathy for either Jews or communists. In late 1935, in a leaflet drafted by the Reichskriegsministerium, Soviet party functionaries were referred to as “mostly dirty Jews” (meist dreckige Juden).12 Four years later, the Allgemeine Wehrmachtsamt of the Wehrmacht High Command (OKW), subsequently heavily involved in the planning of Operation Barbarossa, published a training brochure titled “The Jew in German History” that spelled out what remained to be done regarding the “Jewish question.” All traces of “Jewish influence” were to be eradicated, especially in economic and cultural life; in addition, the “fight against world Jewry, which tries to incite all peoples of the world against Germany,” had to be continued.13 Firmly enshrined in anti-Jewish policy and supplemented by a barrage of propaganda, the phantom of “Jewish Bolshevism” had by June 1941 assumed a life of its own that drastically diminished the military’s ability to perceive reality. The involvement in the murder of Jews and other civilians during Operation Barbarossa of staff officers who were later to support the military opposition against Hitler indicates their acceptance of basic Nazi notions.14 In view of the willing self-integration of leading Wehrmacht officers into the upper echelons of the Third Reich and their support for Hitler’s course toward war, Nazi ideology with its focus on an internal and external enemy provided not a strait-jacket but a fitting new uniform for traditional sets of belief.

If the German army’s commanding officers harbored a deep-seated animosity toward communist Russia combined with an ingrained as well as politically motivated anti-Semitism, this cannot be said with the same certainty of the Wehrmacht’s rank and file. For young recruits of 1941, World War I, though an important part of family history, school education, and national memory, seemed remote. Most of them knew “the east” only from books, school lessons, and propaganda. The German attack on Poland in September 1939 had been orchestrated by a campaign of lies about what the Poles had done to a former (and future) area of German settlement. So far, little research has been done on the role of ideological indoctrination in the behavior of Wehrmacht soldiers or, for that matter, any other group deployed in the east; the prevailing though largely unsubstantiated assumption has been that efforts in this direction were largely futile.15

It has to be taken into account, however, that beginning with the Polish campaign, Nazi propaganda had its strongest ally in German occupation policy itself. As the measures adopted rapidly worsened conditions in the east, despised elements of the local population appeared increasingly subhuman, and this in turn helped to erode remaining moral scruples among German soldiers who had to deal with them. Nowhere was this vicious circle of dehumanization more obvious than in the case of Polish Jews, who came to be presented and perceived as the personification of the Nazi caricature of the “eternal Jew.” Atrocities committed by both SS and Wehrmacht in the Polish campaign were at least partly the result of this imagery and the “master race” or Herrenvolk mentality systematically fostered since 1933.16

After the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact on August 23, 1939, anti-Bolshevism had to be toned down in public.17 At the same time, the death toll during the Polish and other campaigns had started to erode the relative homogeneity of the prewar officer corps, a development greatly accelerated after the beginning of Operation Barbarossa with its heavy losses, especially among lower-ranking troop officers.18 Even if, as is often claimed, the success of deliberate attempts at selling Nazi notions to the soldiers was limited before June 1941, the ideologically highly charged atmosphere and the conditions at the eastern front had a massive impact on how the members of the Wehrmacht perceived and legitimized what they did. At least until Stalingrad, German soldiers mentally endured the hardships of the campaign against a determined enemy not only out of sheer obedience or compliance with group pressure but also because of certain convictions, including the projection of their own destructive impulses onto the enemy.19

In this respect, the political leadership’s sense of reality turned out to be correct. In his speech before army leaders on March 30, 1941, in which he called for the “destruction of Bolshevist commissars and the communist intelligentsia” (Vernichtung der bolschewistischen Kommissare und der kommunistischen Intelligenz), Hitler advised his officers to give orders “in harmony with the sentiment of the troops” (im Einklang mit dem Empfinden der Truppe).20 In mid-September 1941, in one of his nightly musings about the recent past, Hitler conceded that at the time of the attack he had expected expressions of procommunist sentiments within the Wehrmacht. “Those who took part in it,” he assumed, “have now surely learned their lesson, but before no one knew how it really looked over there.”21

The Nazi concept of ideological war implied replacing traditional rules of discipline and subordination with a more flexible system that allowed German functionaries on all levels to act promptly and aggressively. In early May 1941 Colonel General Hoepner, commander of Panzer Group 4, which was to be deployed with Army Group North, legitimized the coming war as a “defense of European culture against a Muscovite-Asiatic deluge” (Verteidigung europäischer Kultur gegen moskowitisch-asiatische Überschwemmung) and a “warding off of Jewish Bolshevism” (Abwehr des jüdischen Bolschewismus)22 Days later, General Müller stated, in regard to the treatment of commissars and the local population, that this campaign would be different from previous ones; the Wehrmacht had to expect resistance from the “carriers of Jewish-Bolshevist ideology,” and it was called upon to shoot “locals who participate in the fighting as partisans or intend to do so . . . during battle or while trying to escape.” Any crimes committed by members of the Wehrmacht as a result of “exasperation about atrocities or the decomposition efforts by the carriers of the Jewish-Bolshevist system” were not to be persecuted as long as they did not threaten discipline.23 This was the tenor of the Erlass über die Ausübung der Gerichtsbarkeit und über besondere Massnahmen der Truppe (Decree on the exercise of military court jurisdiction and special measures of the troops) signed by Keitel on May 13, 1941, and sent down by Brauchitsch to the level of army commanders on May 24.24

The line drawn between “legitimate” and “unacceptable” activities of the local population remained elusive, allowing a wide range of interpretation. In a meeting of intelligence (I c) officers, General Müller’s leading legal expert explained that in deciding whether a crime committed by a German soldier threatened the discipline of the troops, his motivation for the crime should be the key factor.25 The OKW’s Abteilung Wehrmachtspropaganda (Division of Military Propaganda) had issued guidelines for the conduct of the campaign in Russia which called for “ruthless and energetic measures against Bolshevist instigators, partisans, saboteurs, Jews, and total eradication of any active or passive resistance.”26 In their final version, the guidelines stressed the “sub-human nature” (Untermenschentum) of the future enemy.27 OKW chief Keitel signed the “commissar order” on June 6, 1941;28 shortly thereafter, his department for POWS laid down plans for the treatment of captured Red Army soldiers (commissars and Jews were not mentioned) that followed the guidelines regarding the treatment of the population at large.29

It is widely accepted that “the troops of ideological warfare”—the members of the Einsatzgruppen—were motivated by firm ideological convictions. Compared with the three million soldiers who flooded across the border, Heydrich’s Einsatz- and Sonderkommandos seem almost insignificant in size. The majority of Einsatzgruppen personnel came from outside the Security Police and the SD. Units of the Order Police and Waffen-SS fulfilled similar functions either within or outside the Einsatzgruppen framework. The question raised by Christopher Browning in his pathbreaking case study of Reserve Police Battalion 101 as to how “ordinary” these men were needs to be extended to all direct perpetrators.30 The absence of comparative research makes it difficult to come up with more than general conjectures. It seems evident, however, that the issue is very much linked to the institutional history of the SS and police in the Third Reich.

Since the mid-1930s ideological training had been part of the curriculum of German policemen. After 1936 when Himmler was appointed chief of the German police, in addition to his position as Reichsführer-SS, he felt the need to integrate more firmly the component parts of his empire. On the organizational level, these efforts proved largely futile owing to the intense rivalry between the different agencies within his apparatus. The office of HSSPF, designed to link SS and police functions, in fact increased the degree of decentralization by creating “little Himmlers” bound into the existing structure by their personal allegiance to the Reichsführer rather than by bureaucratic ties.31 On the ideological level, however, the self-image of a Staatsschutzkorps (state defense corps)—a diversified security agency that would defend the Reich against inner enemies just as the Wehrmacht provided protection against external foes—began to take root among the officers of the SS and police even before the war.32 Regarding the Jewish question, the term “education for murder” coined by Konrad Kwiet aptly describes the long-term effects of this process.33 As Ian Kershaw has pointed out, propaganda “was above all effective where it was building upon, not countering, already existing values and mentalities.”34 Like Wehrmacht soldiers and the German population at large, members of the SS and police were subjected daily to anti-Semitic messages. Gripping images like in the 1940 movie Jud Süss (The Jew Süss) reinforced what was taught in police and SS schools.

Indoctrination was not an end in itself, but closely linked to political practice. Beginning with the enactment of the first anti-Jewish measures and the upsurge of street violence against Jews after January 1933, the police formed an integral part of the machinery that generated the “Final Solution.” Even if policemen harbored no anti-Semitic feelings beyond what was considered “normal” in prewar Germany, the activities of Nazi thugs, opportunistic profiteers, and eager bureaucrats deeply affected individuals of all ranks as well as the police as an institution. Prejudices, indoctrination, and the ever increasing practice of persecution made SS and policemen perceive the Jewish question not in abstract terms but as a pressing problem that—for the benefit of the regime, the security apparatus, and their own careers as well—needed to be addressed. The focus on transmitting applicable as opposed to abstract knowledge meant that many of the teachers and students at SS and police schools were members of the Einsatzgruppen and that, in turn, officers involved in “fieldwork,” like Adolf Eichmann, lectured at these schools.35

Ideological factors operated on many levels. In compiling reports on what happened on Soviet territory before Operation Barbarossa, German agencies could rely to some extent on the help of local informers. In the Baltic States or western Ukraine, annexed to the Soviet Union after 1939, the anti-Semitic bias of nationalists dovetailed with the prejudices of German officials. Lithuanian activists who had fled their country as a consequence of the Soviet takeover formed an especially important group. Via the Stapostelle Tilsit, the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) Amt IV (Gestapo) in Berlin received regular reports from across the border with Lithuania that were sometimes read by Heydrich and Himmler. In late May 1941 the Tilsit Stapo office under Hans-Joachim Böhme noted changes in the composition of communist functionaries in Lithuania in favor of Russians and Jews. “The Jews in Soviet Lithuania,” Böhme concluded, “are primarily active as spies for the Soviet Union.”36

Prewar orders by the German military leadership regarding the future treatment of captured Red Army soldiers and political commissars leave no doubt about the importance of ideological factors preceding Operation Barbarossa. These orders were more radical than Heydrich’s prewar instructions to the Einsatzgruppen, which called for the destruction of specific, though vaguely defined, groups of the population. However, Heydrich had reason to believe that Security and Order Police officers were less influenced by the wording of directives than by their own interpretation of what needed to be done in the east. Before the attack on Poland, Heydrich had charged the Einsatzgruppen with fighting all inimical elements behind the front line (Bekämpfung aller reichs- und deutschfeindlichen Elemente in Feindesland rückwärts der fechtenden Truppe), similar to the task of the Security Police in the Reich. This formula provided unit commanders with sufficient legitimization for acts of terror directed against the Polish population.37 Based on this experience, in 1940 Heydrich issued more stringent guidelines for the deployment of Security Police and SD in Norway. While “enemies of the Reich” were to be neutralized, the “necessity for an absolutely correct conduct” had to be taken into account. All measures had to be implemented “with the greatest sensitivity toward tact,” since this was not “a campaign on enemy territory.”38 For the Balkan campaign in spring 1941, no such caveat seemed necessary; in fact, Heydrich came up with a much wider definition of enemy groups that included communists and Jews.39 In planning for Operation Barbarossa, it must have been clear to the leader of the Security Police and the SD that the likelihood of his officers in the field committing acts of violence against the civilian population increased with the vagueness of the guidelines issued to them.

EARLY ANTI-JEWISH MEASURES AND THE MID-JULY TURNING POINT

Despite the design of the campaign as a war of destruction against the Red Army, potential enemies of German rule, and millions of unwanted civilians, some remaining barriers still had to be overcome on the way to the Final Solution. In June 1941 a solution to the Jewish question was still envisioned by the German leadership in terms of forced resettlement that, though inherently destructive, did not amount to the systematic mass murder of all Jewish men, women, and children. Precedents set in the early weeks of the Barbarossa campaign would prove crucial in the turn to systematic and total mass murder.

The area first affected by the German war machine’s deliberate targeting of civilians was the German-Lithuanian border strip. In the early morning hours of June 22, a battalion of the 176th Infantry Regiment launched its attack on the town of Garsden (Gargždai) but faced heavy resistance from Soviet border troops. Surprised by the Germans and armed only with handguns, these units defended parts of the town until, in the afternoon, they were almost completely wiped out by the overwhelming force of the enemy. Infantry Regiment 176 suffered more than 100 casualties on this first day of the war—among them 7 dead officers. In advancing further east, it left securing the town to German border police (Grenzpolizei) from the city of Memel. The Memel unit, with the assistance of local Lithuanians, separated 600 to 700 Jews from the rest of the civilian population. The border police were not sure how to proceed, and telegraph messages were exchanged between Memel, the Stapostelle Tilsit, and the RSHA.40

The next morning, while Berlin remained undecided about what to do, the leader of the Stapostelle Tilsit, Hans-Joachim Böhme, the officer who had transmitted reports from Lithuanian informers to Berlin before the war, ordered the border police to select 200 male Jews from among the detainees. They were then marched, together with one woman, across the border to a field where they were guarded by members of the German customs service. It is not clear what instructions were issued to the Stapostelle Tilsit before the attack. During his trial in the late 1950s, Böhme claimed to have received three orders from the RSHA: one regarding the closing of the border, a second outlining the tasks of the Einsatzgruppen—to which his unit did not belong—and the third regarding executions in the border area. Since the Tilsit Stapostelle and SD did not have enough men for the execution of the 201 Garsden Jews, the police commander in Memel supplied upon request a Schutzpolizei (Schupo) platoon of one officer and 25 men. On June 23 the platoon rehearsed the execution in the police barracks before driving the next day to Garsden, where Böhme and the Tilsit SD leader Werner Hersmann were waiting for them. While waiting for their execution, the Jews—among them old men, the wife of a Soviet commissar, and at least one 12-year-old child—had to hand over their possessions and dig their grave. Security Police and SD men of the Stapoleitstelle Tilsit abused the victims, especially an old rabbi with a beard and caftan; one person was shot for not digging fast enough.

In the early afternoon of June 24, the remaining 200 Jews were executed in a court-martial-like procedure that included the reading of the death sentence “for crimes against the Wehrmacht on order of the Führer” and the Schutzpolizei officer, with sword drawn, giving the order to fire. Victims and perpetrators were no strangers to each other. Many of the Jews living in Garsden at the time of the German attack had escaped from Memel after its incorporation into the Reich in early 1939. Decades later, some of the defendants and witnesses in the West German court case remembered the names of the victims. According to the verdict, the soap manufacturer Feinstein from Memel called out to his former friend and neighbor, a police sergeant who stood in the firing squad: “Gustav, shoot well!” After the execution, the Memel Schutzpolizei men discussed what they had done. In reassuring each other, comments were made like “Good heavens, damn it, one generation has to go through this so that our children will have a better life.” (Menschenskinder, verflucht noch mal, eine Generation muss dies halt durchstehen, damit es unsere Kinder besser haben.)41

On June 24 Böhme and Hersmann met with Brigadeführer Franz Walter Stahlecker, the chief of Einsatzgruppe A. During the postwar judicial proceedings, the defendants claimed that Stahlecker had ordered Böhme to shoot all Jews in the border area including women and children.42 However, wartime evidence suggests that this was not the case. In a report sent to Berlin about a week after the first mass execution, Böhme wrote only that Stahlecker gave his “general approval to the cleansing actions” (grundsätzlich sein Einverständnis zu den Säuberungsaktionen erklärte) close to the border.43

From Garsden, Böhme’s unit, now referred to as Einsatzkommando Tilsit, moved on. After joining the Wehrmacht in shooting 214 persons including one woman in the town of Krottingen and 111 “persons” in Polangen for allegedly attacking German soldiers, Böhme’s men met with Himmler and Heydrich in Augustowo on June 30. Again, the wording of Böhme’s report on what was discussed is crucial for understanding the situation at the beginning of Operation Barbarossa: “The Reichsführer-SS [Himmler] and the Gruppenführer [Heydrich] who by coincidence were present there [in Augustowo] received information from me on the measures initiated by the Stapostelle Tilsit [italics mine] and sanctioned them completely.” (Der Reichsführer-SS und der Gruppenführer, die dort zufällig anwesend waren, liessen sich über die von der Staatspolizeistelle Tilsit eingeleiteten Massnahmen unterrichten und billigten diese in vollem Umfange.) Böhme also mentioned consultations with state officials—the Regierungspräsident in Gumbinnen, the East Prussian Oberpräsident and Gauleiter Erich Koch, who was soon to become Reichskommissar for the Ukraine—about incorporating parts of the occupied border regions into Eastern Prussia. Böhme’s unit continued its killing spree in Lithuania, claiming by July 18, 1941, a total of 3,302 victims.44

South of the Lithuanian sector of the front, equally destructive precedents were being set. Few of the early killings show as obvious a link to Jew-hatred as the mass murder of Jews in Bialystok on June 27, 1941, in which men of Police Battalion 309 and other units subordinated to the Wehrmacht’s 221st Security Division killed at least 2,000 Jews. More than 500 persons including women and children were driven into a synagogue and burned alive; those trying to escape were shot. Wehrmacht units blew up adjacent buildings to make sure that the fire did not spread across the city. The scarcity of wartime documentation on this massacre is to some extent compensated for by investigative material compiled by a West German court after the war.

After an order had been given to search for Red Army soldiers and Jews, a few determined officers initiated the murder and dragged others along. The West German court identified some of the perpetrators within the ranks of Police Battalion 309 as “fanatic Nazis,” such as “Pipo” Schneider, a platoon leader in the 3rd company; and Captain Behrens, commander of the 1st company. Schneider showed little respect for military obedience, openly dismissing his company commander as a “cowardly weakling,” and made no secret of his conviction that the Führer would “no longer feed these dirty Jordan slouchers” (diese dreckigen Jordanlatscher nicht mehr am Fressen halten). Together with Behrens, Schneider transformed his ideas into action. Jewish men whose outward appearance corresponded to anti-Semitic stereotypes became their first victims: beards were set on fire, some Jews were forced to dance or to cry “I am Jesus Christ,” and Orthodox Jews were shot in the streets. A police officer who expressed discomfort at such acts was rebuked with the words “You don’t seem to have received the right ideological training yet.” (Du bist wohl ideologisch noch nicht richtig geschult.) Higher-ranking officers—among them the battalion commander and the commanding general of the 221st Security Division—stood by. The general did not begin to take notice that men under his command were running amok until the executions had reached a park next to his headquarters, and he later tried to cover up the massacre as a reprisal.45

The mass murders in Garsden and Bialystok in late June reflect most of the features of what Raul Hilberg has called the “first killing sweep.”46 The perpetrators used their image of the “enemy” and the pretexts of “retaliation” and “pacification” to legitimize the selection and execution of undesirable persons, primarily Jews, without waiting for specific orders from above. If the murder of Jews on occupied Soviet territory did not result from a preconceived master plan,47 the sequence, speed, and scope of the killings must have been connected to regional factors and the dynamics of ad hoc decision making. In the process, traditional elements of hierarchy lost their importance. Men from different agencies—the Security Police, the Wehrmacht, the Order Police—interacted. The authority to inflict suffering and death on civilians became detached from military rank and status, with lower- and middle-ranking officers taking the initiative while their superiors provided support, encouragement, or ex post facto legitimization. In this way the limits of what was regarded as acceptable in dealing with selected groups within the civilian population were expanded.

This approach did not become standard procedure overnight. At the time of the killings in Garsden, the 10th Regiment of the 1st SS Brigade, which as part of the Kommandostab was deployed further south, understood its task of “cleansing the border regions” in a much narrower way than Einsatzkommando Tilsit. Instead of killing civilians, it seems to have merely guarded bridges.48 Through the month of July, however, additional units available to Himmler—his Kommandostab and battalions of Order Police—increasingly became involved on a massive scale in mass murder, thus marking the end of the first stage of destruction.

As they did in the meeting with Böhme in Augustowo, Himmler and his leading officers fomented the local killing process, often in more subtle ways than by directly ordering what was to be done. Frequent visits by Himmler, the HSSPF, Heydrich, or Daluege ensured that word about the “success” of radical measures got around quickly and that officers who were reluctant or tardy adapted to the new possibilities.49

How the presence of high-ranking officials influenced the course of events in the field can be seen from the visits by Himmler, Daluege, and Bach-Zelewski to Bialystok in early July 1941. Hours before Himmler arrived in the city, Police Battalion 322 had looted the Jewish quarter, taking out 20 truckloads of food and other supplies, but it did not massacre Jews like Police Battalion 309 just days earlier. In fact, the three persons shot by Police Battalion 322 were Poles.50 After his arrival the Reichsführer-SS addressed Bach-Zelewski; the commander of the Rear Army Area Center, von Schenckendorff;51 the commander of Police Regiment Center (to which Police Battalion 322 belonged), Max Montua; and the officers of Police Battalions 322 and 316 as well as of the SD. According to postwar testimonies by participants, Himmler talked about the organization of the police in the east and inquired about the measures taken that day in the Jewish quarter. One witness claimed to have heard from others at the time that Himmler had complained about the small number of Jews arrested and had called for a more active course in that direction.52 One day later, on July 9, Order Police chief Daluege came to visit Police Regiment Center in Bialystok and delivered a speech on the fight against the “world enemy of Bolshevism.” Between July 8 and July 11, perhaps even starting on the evening of Himmler’s visit, at least 1,000 Jews—all men of military age—were driven to the outskirts of the city, where they were shot by members of Police Battalions 322 and 316 under the direction of the Security Police and the SD.53 This sequence of events in Bialystok seems to imply a causal connection, but at the very least encouragement from above had the effect of speeding things up. However, in light of the earlier massacre in Bialystok in late June and other mass killings in localities that high-ranking officers from Berlin had not visited, it seems evident that the presence of the Reichsführer-SS and his lieutenants was not required to trigger the murder of Jews.54

On July 11, 1941, possibly in reaction to the earlier killings by Order Police units in Bialystok,55 the commander of Police Regiment Center, Montua, transmitted an order by HSSPF Bach-Zelewski according to which all Jews age 17 to 45 convicted of plunder were to be shot (“alle als Plünderer überführten Juden im Alter von 17–45 Jahren sofort standrechtlich zu erschiessen”). To prevent “places of pilgrimage” (Wallfahrtsorte), the executions had to be carried out in a clandestine way and reported daily; no photographs or onlookers were allowed. The following piece of advice Bach must have received, directly or indirectly, from Himmler, whose concern for the well-being of his officers was notorious: “Battalion commanders and company chiefs have to make special accommodations for the spiritual care of the men participating in such actions. The impressions of the day have to be blurred by having social gatherings. In addition, the men have to be continuously lectured about the necessity of measures caused by the political situation.” (Die seelische Betreuung der bei dieser Aktion beteiligten Männer haben sich die Batls.-Kdre. und Kompanie-Chefs besonders angelegen sein zu lassen. Die Eindrücke des Tages sind durch Abhaltung von Kameradschaftsabenden zu verwischen. Ferner sind die Männer laufend über die Notwendigkeit der durch die politische Lage bedingten Massnahmen zu belehren.)56

By visiting their men behind the front line, Himmler and some of his closest associates both provided and gathered important information on how to synchronize the “pacification” efforts. But while backing what had been done already and appealing to the men’s sense of initiative in a rapidly escalating situation, they did not call directly for the killing of unarmed civilians irrespective of age or gender. The absence of specific orders from Berlin to kill all the Jews east of the border is reflected in the fact that the incoming reports described the first victims of physical annihilation as local Jewish men of military age, especially Jewish intelligentsia in leadership positions in the community.57 However, from the beginning the delineation of the target group was not clear-cut. The massacre in Bialystok on June 27 shows the perpetrators’ lack of inhibitions about killing even those Jews who were the least suspicious and the most vulnerable. And among the 201 persons shot in Garsden on June 24 there were a boy, one woman, and several Jews from Memel who but for the Nuremberg laws were German.

To some extent, the sequence of German anti-Jewish measures adopted in the occupied Soviet Union followed the model first established in Poland. In contrast to the Polish campaign and its aftermath, however, during Operation Barbarossa arrests, confiscation of property, exclusion from certain professions, introduction of badges or other markings, and separation from the gentile population were from the beginning directly linked with numerous acts of mass murder perpetrated by different agencies. Recent research has confirmed that in many cases units of the Wehrmacht delivered the first blows.58 More-systematic steps were later taken by the Security Police and the SD as well as, in the Reichskommissariate, by representatives of the civil administration. What might appear from a post-Holocaust perspective as a centrally planned and uniformly applied pattern of stigmatization, dispossession, concentration, and annihilation was in the first months of Operation Barbarossa an incoherent, locally and regionally varied sequence of measures characterized on the part of German officials by increasing violence and its acceptance as normality in “the east.”

The destructive energies released by the German attack on the Soviet Union were primarily directed against the enemy army. In any military campaign troops can perpetrate atrocities, but Operation Barbarossa was an exceptional war for which the German leadership had deliberately defined new parameters of conduct. Criminal orders from above and violent impulses from below created a climate of unmitigated violence. This can be seen from the available evidence on the killing of captured Red Army soldiers by frontline troops and the conditions in camps for Soviet POWS and civilians.59 In late June in the city of Minsk the local military commander established a camp that housed at times up to 100,000 Soviet POWS and 40,000 civilians, predominantly men of military age. Conditions in the camp were terrible; even Germans voiced their disgust.60 In the following weeks, units of the Security Police and SD in conjunction with the army’s Secret Military Police (Geheime Feldpolizei) screened both prisoner groups, taking out an estimated 10,000 for execution. Many of the men selected were Jews; however, a significant number of Jews were also among the approximately 20,000 persons released from the Minsk camp in mid-July.61

As in preinvasion memoranda and plans, German officials in the field hid ideological bias behind practical rationalizations, mostly by presenting anti-Jewish measures as part of a wider policy of “pacifying” the occupied area. This is true of the events in Bialystok and of a number of other killings. In late June/early July, units of the Waffen-SS Division “Wiking” were, according to a report by a staff officer of the 295th Infantry Division, randomly shooting large numbers “of Russian soldiers and also civilians whom they regard as suspicious,” among them most likely 600 Jews in Zborov in Ukraine.62 Following a request from the 6th Army, SK 4a of Einsatzgruppe C killed 17 non-Jewish civilians, 117 “communist agents of the NKVD,” and 183 “Jewish communists” in Sokal. According to Hoepner, commander of Panzer Group 4, “individual communist elements, especially Jews,” were responsible for the “rather rare instances of sabotage.”63 In Drobomil, EK 6 arrested approximately 100 persons, mostly Jews, under the pretext of retaliation for NKVD murders and shot them. Reports on events in Kaunas (Kovno), LWOW (Lemberg), and Tarnopol (Ternopol) linked the execution of Jews to earlier killings of prisoners by Soviet authorities, thus artificially creating a causal connection that ignored the Jews among the NKVD victims and helped to gloss over the anti-Jewish feeling of German units.64 Sometime before mid-July, 4,000–6,000 male Jews in the western Belorussian city of Brest were arrested and shot by men of Police Battalion 307 and the 162nd Infantry Division as part of a “cleansing action.”65 In Lithuania, German security agencies continued setting precedents that were later to become a standard part of the overall process. In early July 1941 SS Colonel Karl Jäger of EK 3 reported that 7,800 Jews had been killed so far in Kaunas “partly by pogrom, partly by mass executions.” To systematically “cleanse” the countryside of Jews, a small mobile unit was set up; in Kaunas, a ghetto was to be created within the next four weeks.66

All along the front line, German military and police agencies executed Jews in reprisal for alleged attacks on troops or for being plunderers, members of the intelligentsia, saboteurs, or communists. Beginning in mid-July, Jewish communities were confined to “Jewish quarters” in segregated parts of towns and cities.67 Central though hardly coherent guidelines regarding ghettoization were issued weeks later.68 How great an area could be “secured” and “pacified” depended to a large extent on the working relationship between leading Wehrmacht and Einsatzgruppen officers.69 In the Latvian city of Liepaja, where shots were occasionally fired at Wehrmacht soldiers, the navy commander in late July requested and received the help of police forces for solving the Jewish problem.70 Einsatzgruppe B leader Arthur Nebe reported that the “excellent” (ausgezeichnet) cooperation with the Army Group Center “has proven to be successful especially in the liquidation actions in Bialystok and Minsk and has not failed to affect other commandos.” (Diese Methode hat sich besonders bei den Liquidierungs-Aktionen in Bialystok und Minsk gut bewährt und ihre Wirkung auf die übrigen Kommandos nicht verfehlt.)71 Dieter Pohl has estimated that in Eastern Galicia SS and police units killed more than 7,000 Jews by the end of July 1941, before the area was incorporated into the General Government.72 At the same time, Einsatzgruppe B reported 11,084 murder victims, predominantly Jews.73 For all the Einsatzgruppen, the total at the end of July was 63,000 persons, about 90% Jews.74 The perpetrators no longer thought of total annihilation as a utopian idea. In early July a member of Reserve Police Battalion 105 wrote home to Bremen that “the Jews are free game. . . . One can only give the Jews some well-intentioned advice: Bring no more children into the world. They no longer have a future.” (Die Juden sind Freiwild. . . . Man kann den Juden nur noch einen gut gemeinten Rat geben: Keine Kinder mehr in die Welt zu setzen. Sie haben keine Zukunft mehr.)75

The killings in the first five weeks of Operation Barbarossa were of crucial importance for the later sequence of events. What had previously been regarded as logistically difficult, morally questionable, and politically dangerous became a new point of reference for German occupation policy. Starting in Garsden and Bialystok, the last taboo—the killing of women and children—eroded. On July 3 the I c officer of the 295th Infantry Division reported from Zloczow that “Jews and Russians including women and children” were murdered in the streets by Ukrainians.76 From Lithuania, Jäger’s EK 3 was reporting small but increasing numbers of women among the victims of executions.77 In late July significant numbers of women seem to have been among the victims of pogroms in LWOW and Grodek Jagiellonski.78 Police Regiment Center ordered its subordinate police battalions to provide execution statistics specifying the number of Russian soldiers, Jews, and women shot.79 Around the turn of July/August 1941, other units—the 1st SS Brigade subordinated to HSSPF Jeckeln, Einsatzgruppe B (EK 9) and C (SK 4a)—started to shoot women and children in larger numbers.80 In early August the previously quoted member of Reserve Police Battalion 105 from Bremen wrote: “Last night 150 Jews from this village were shot, men, women, and children, all killed. The Jews are being totally eradicated.”81

By that time, a standardized method of mass murder had been adopted. The Jews were first rounded up, then brought, in groups of varying size depending on circumstances, to a more or less remote execution site, where the first arrivals were forced to dig a pit. The Jews had to undress and line up in front of the mass grave; they were then either shot into the pit or were murdered after being forced to lie on top of those already killed.82 What the perpetrators presented as an “orderly” execution procedure was, literally, a bloodbath. In the vicinity of cities, what could be called “execution tourism”—all kinds of Germans on or off duty looking on and taking pictures—abounded despite orders to the contrary.83 Unlike the execution in Garsden, in later killings the reading of a verdict, however fabricated, was dispensed with. No officer gave a command to fire; instead, the executioners shot randomly, often with submachine guns. Coups de grâce were rarely delivered, and those who were shot but not immediately killed were left to die from their wounds or from suffocation after the pit was covered with soil. “Order” was restored for the murderers at the end of the day when they reentered the world of seemingly normal values or when they attended, as advised by Himmler, their “social gatherings.”84

As in the planning stages of Operation Barbarossa, economic considerations were but one factor that guided German policy toward the Jews. While the army and later the civil administration stressed the need for qualified Jewish laborers, early experiences pointed to their dispensability. For the Wirtschaftsstab Ost, the case of the oil refinery in Drohobycz (Drogobych) initially seemed to prove that Jewish experts were needed only for a short transition period. Since things worked well without any Jews (ganz judenfrei), it recommended that they should be confined to ghettos.85 Ghettoization had the additional advantages of providing economic opportunities for Germans and reliable locals and of excluding Jews from the food market. According to Göring’s economic experts, skilled Jewish laborers were to remain employed in the war industry only if they were crucial for maintaining the required level of production and could not be replaced.86 In late July, Berlin economic planners abandoned the grand designs for economic policy developed before the war in favor of practical measures for the immediate benefit of the war effort. For the Jews, that meant concentration in ghettos and forced labor in work columns.87 Nevertheless, there was uncertainty about which Jews should be killed and which should be regarded as temporarily indispensable. As the Wirtschaftsstab Ost phrased it in its first report: “Unresolved is the question of the Jews who at this time remain deadly enemies, but who are at least temporarily large number.” (Ungelöst Frage der Juden, die diesmal Todfeinde bleiben und doch wirstschaftlich wegen grosser Zahl mindestens vorläufig notwendig.)88 Those responsible for the enactment of anti-Jewish measures noted that their victims tried to make sense of the confusing and contradictory German measures, often by assuming “that we will leave them alone if they eagerly do their work.”89

In this rapidly changing situation, contact between the command centers and the units in the field were of mutual benefit. When on June 29, 1941, Heydrich reminded the Einsatzgruppen chiefs of the need for “self-cleansing measures” by the local population, he also insisted that leaders of advance units had to have “the necessary political sensitivity” (das erforderliche politische Fingerspitzengefühl) and requested regular reports.90 On July 1 Heydrich demanded “a maximum of mobility in the organization of tactical operations” (grösste Beweglichkeit in der taktischen Einsatzgestaltung) by pointing to his unsatisfactory experience in Grodno, where during a visit four days after the occupation of the city, he and Himmler had not found one representative of the Security Police and the SD.91 The following day he notified “in condensed form” the HSSPFS—who had been dispatched to the east after having met with Daluege, but not with Heydrich—about the “most important instructions” issued to the Einsatzgruppen: to further the final aim of “economic pacification” (wirtschaftliche Befriedung), stern political measures were to be adopted. The list of persons to be executed comprised functionaries of the Communist Party, people’s commissars, “Jews in party and state positions,” and “other radical elements (saboteurs, propagandists, snipers, assassins, instigators etc.).”92 We can tell from the reasoning for mass killings offered in the reports from the Einsatzgruppen, Wehrmacht, and police units that Heydrich’s categories in fact described the prime target groups. It is not clear, however, whether incoming reports from the field were tailored to meet the instructions from Berlin or whether Heydrich tried to adapt his somewhat belated notification to the actions of his subordinates behind the German front line.

Heydrich’s obsession with monitoring the activities of his units behind the advancing front line stemmed largely from the fear of going too far too quickly, a fear he shared with Himmler. At this stage, instead of providing explicit orders for the rapid expansion of the killing process, the SS and police leadership in Berlin seems to have followed a course that can be described as controlled escalation. The delegation of power in the absence of unambiguous guidelines from above greatly increased the danger of subordinate officers getting out of control; thus, reliable information about what went on in the field was crucial. The incoming reports from the Einsatzgruppen were edited at the RSHA and, in the form of the so-called Ereignismeldungen, distributed to other government agencies in order to inform them about as well as adapt them to the course of events in the east. Himmler’s infamous speech of October 1943 in which he talked to a large audience of Nazi officials about the implementation of the Final Solution was not his first attempt at spreading responsibility for the murder of the European Jews.93

Officers at the periphery could expect that their reports would be received by an influential circle of high-ranking officials. For the purpose of presenting it to Hitler, the RSHA gathered “illustrative material” (Anschauungsmaterial) on the “work of the Einsatzgruppen in the east.”94 On July 4 Heydrich reiterated his supreme interest in functioning communications between periphery and center while announcing that local Security Police and SD offices in the border region were authorized to perform “cleansing actions” in occupied territory after consultation with the Einsatzgruppen. Heydrich might have had the case of Böhme’s Einsatzkommando Tilsit in mind when he threatened to withdraw this authorization if these additional units intended “further actions” (ein weiteres Vorgehen) beyond those agreed upon with the Einsatzgruppen “for the purpose of operational coordination” (zwecks einheitlicher Ausrichtung der zu ergreifenden Massnahmen).95 As late as mid-August the Reichsführer-SS sent out reminders for regular reports to his most trusted officers deployed in the east.96

In the minds of Himmler and Heydrich, the potential dangers of excessive zeal were manifold. First, despite the cordial relations in the field and the agreement between Wagner and Heydrich, the army could still be antagonized to such a degree that the conflicts of the Polish campaign might reemerge. Second, the thin, but for internal as well as external reasons essential, veil of secrecy could tear, exposing the true nature of German measures in the east. Richard Breitman has recently shown that this fear was indeed well founded, since the British had broken the German Order Police code for radio messages and intercepted execution reports and other incriminating material.97 Third, Himmler was committed to caring for the psychological needs of his men, and he feared that the persistent use of extreme violence posed a threat to the coherence, loyalty, and postwar effectiveness of the troops. Fourth and most important, given the Nazi leadership’s obsession with preventing a situation similar to 1918, the quiet on the home front was not to be endangered. Economic considerations that already in the planning stages of the war enabled the branding of entire groups of the local population as redundant and dispensable were not an end in themselves but resulted to a significant degree from the Nazi leaders’ determination to avoid putting an undue burden on the German Volk. Concern about potential unrest led to the official stop of the “euthanasia” killings (Aktion T4) in August 1941. “The Führer,” Heydrich explained to his subordinates in early September, “has repeatedly stressed that all enemies of the Reich use—like during the [First] World War—every opportunity to sow disunity among the German people. It is thus urgently necessary to abstain from all measures that can affect the uniform mood of the people.” Heydrich ordered that “my approval is sought before taking any especially drastic measures” but left a loophole in cases of “imminent danger.”98

As before, Hitler himself displayed trust in the rapid adaptation of his men and the population at large. While he initially expected that some Wehrmacht soldiers still harbored sympathy for communism,99 he was nevertheless sure that the situation across the border would have the desired effect of removing remaining inhibitions. His orders regarding the treatment of Soviet POWS and the civilian population contributed decisively toward this development. In addition, the German propaganda machine expanded on existing stereotypes by stressing that “millions of German soldiers are witnesses today of the barbarity and wretchedness of the Bolshevist state.” (Heute sind Millionen deutscher Soldaten Zeugen der Barbarei und der Verkommenheit des bolschewistischen Staates.) What they saw there went, according to the official line, far beyond anything known so far about “the Jewish slave state.” (Ihre furchtbaren Einblicke in die Verhältnisse dieses jüdischen Sklavenstaates stellen das in den Jahren bisher dem deutschen Volk bekannt Gewordene noch weit in den Schatten.)100

Recent evaluations of letters and photographs by Wehrmacht soldiers point to a certain discrepancy between propaganda slogans and the more complex “eastern experiences” of many Germans. Jews did not figure prominently as objects of photographic imagery or as topics in the correspondence between German soldiers and their families back in the Reich.101 Much more dominant in this phase of the war were the primitive conditions, filth and the lack of hygiene, which over time retreated into the background thanks to what Omer Bartov calls the “barbarization of warfare” that especially affected frontline soldiers.102 In the comparatively few instances when the Jewish question was referred to, Jews were depicted primarily in terms of official propaganda and familiar stereotypes. Accordingly, early dispatches from the east presented Jews as snipers or instigators of atrocities committed against German soldiers. One of the most graphic examples is a letter written from Tarnopol in early July 1941. The writer, after referring to mutilated bodies left by the retreating Soviets in the city’s courthouse, minced no words about what happened next:

Revenge was quick to follow. Yesterday we and the SS were merciful, for every Jew we found was shot immediately. Today things have changed, for we again found 60 fellow soldiers mutilated. Now the Jews must carry the dead out of the basement, lay them out nicely, and then they are shown the atrocities. After they have seen the victims, they are killed with clubs and spades.

So far, we have sent about 1,000 Jews into the hereafter, but that is far too few for what they have done. The Ukrainians have said that the Jews had all the leadership positions and, together with the Soviets, had a regular public festival while executing the Germans and Ukrainians. I ask you, dear parents, to make this known, also father, in the local branch [of the NSDAP]. If there should be doubts, we will bring photos with us. Then there will be no doubts.

Many greetings, your son Franzl.103

In hindsight, the available documentation for the early weeks of the campaign indeed corroborates Hitler’s view that his men would function well and that the unity of the home front was not in imminent danger. At the same time, in his pronouncements before his closest advisers Hitler expressed less interest in the Jewish question than in other, broader problems. This can be seen from the course of a meeting on July 16, 1941, at which Göring, Rosenberg, Lammers, Bormann, and Keitel were to receive Hitler’s view on key issues of policy making. Before addressing the specifics of the issues at hand, Hitler made some general remarks: German propaganda would again have to stress that the Wehrmacht stepped in to restore order and that the Reich was taking over a mandate. However, “all necessary measures”—including shootings, forced resettlement—were to be accelerated, since “we will never leave these areas again.” To achieve “a final settlement” (endgültige Regelung) of German control over the area, it was essential “to cut the gigantic cake into manageable pieces so that we can, first, dominate it, second, administer it, and third, exploit it.” Using Stalin’s call for partisan warfare as a pretext, Hitler stressed the “possibility of eradicating whatever puts itself against us.” (Möglichkeit, auszurotten, was sich gegen uns stellt.)104

Taking up Hitler’s demand to transform the occupied territory into a “Garden of Eden” and his decision to hand over the area west of the river Düna to civil administration, Rosenberg tried to stress the importance of treating the local population differently—for Ukrainians he even envisaged a limited degree of independence.105 Göring objected: all thoughts would have to focus for the time being on securing the food supply. The matter was left undecided, and it might have been in that context that Hitler mentioned—as recorded by Rosenberg in his diary—that “all decrees are but theory. If they do not meet the demands, they will have to be changed.”106 Hitler and his cronies moved on to the issue of sharing some of the territorial spoils with Germany’s allies, followed by lengthy discussions on the relative merits of the various contenders for the positions of Reichskommissare. Here again, everything depended on quick, energetic action. When Rosenberg objected to the idea of having Erich Koch, Gauleiter of East Prussia, administer the Ukraine for fear that he might act too independently, he was told by Göring that he “could not always lead his regional representatives around by the nose, rather they would have to work quite independently.” (Rosenberg könne die eingesetzten Leute ja nun nicht ständig gängeln, sondern diese Leute müssten doch sehr selbständig arbeiten.)107

When Rosenberg brought up the “question of securing the administration,” Hitler stated that he had repeatedly called for better weapons for the police in the east and added, “Naturally, the vast area must be pacified as quickly as possible; this will happen best by shooting anyone who even looks sideways at us.” (Der Riesenraum müsse natürlich so rasch wie möglich befriedet werden; dies geschehe am besten dadurch, dass man Jeden, der nur schief schaue, totschiesse.)108 Field Marshal Keitel stressed that, since one could not guard “every barn and every railway station,” the local population needed to know “that anybody would be shot who did not behave properly and that they would be held responsible.” Although Himmler did not attend this meeting, his interests were taken into account by the other participants and in the order for the establishment of the civil administration drafted by Lammers, the chief of the Reich chancellery.

Rosenberg’s final remarks in his diary reflect the atmosphere during the meeting:

At 8 we were nearly finished. I had received a gigantic task, very likely the biggest the Reich could assign, the task to make Europe independent from overseas countries and to make this safe for centuries to come. I did, however, not receive complete authority, since Göring as plenipotentiary for the Four-Year Plan had the right, for a short while even precedence, to interfere in the economy, which if done without clear coordination could possibly endanger the political aims. In addition Koch in Kiev, the most important city, who will lean more toward Göring than me. I have to watch carefully that my directives are followed. . . . When we parted Göring shook hands with me and expressed his hope for a good collaboration.109

The meeting on July 16 can be interpreted as the clearest expression of what Browning has termed the first turning point in the decision-making process that led up to the Holocaust.110 Linking inclusion and exclusion—the two basic aims that had characterized German resettlement policy since fall 1939—the participants and especially Hitler presented “positive” visions for the German Volk at large that were to transform the rugged east into a “Garden of Eden” while at the same time calling for negative, in fact highly destructive, measures against any sign of noncompliance among the local population. In this context, the correlation between the east and the Jewish question in its broader meaning played an important, yet undefined role. At the time, the Nazi leadership might have shared the doubts expressed at the periphery that mass shootings of Soviet Jews were, as a report by the Kommandostab on the killings in the Baltics put it, the way in which “the Jewish problem can be fundamentally solved” (das jüdische Problem einer grundsätzlichen Lösung zugeführt werden kann).111 Similarly, in early July following the pogroms in Kaunas the commander of Army Group North, von Leeb, had voiced his agreement with Franz von Roques, commander of the Rear Army Area North, that “in this manner the Jewish question will probably not be solved. The most secure means would be the sterilization of all male Jews.”112 Nevertheless, Hitler and the top leadership refrained from addressing the issue and left it to their men in the field to decide how to proceed.

Although the meeting of July 16 did not result in any specific directives in regard to the Jewish question in the east, it was crucial for defining the parameters of subsequent policy. One day later, Hitler signed a set of orders that formally established the civil administration in the occupied east.113 These orders guaranteed that Himmler’s jurisdiction over security matters and Göring’s over the war economy remained intact, thus creating the precarious imbalance of agencies within which Rosenberg and his ministry had to operate.114 At the same time, following the appointment of the first representatives of the civil administration, the persecution of the Jews in the occupied parts of the Soviet Union took on a new, more systematic form.115 Rosenberg’s men found conditions that to a large degree had already been determined by events during the preceding weeks. However, not all of these events, including those leading up to the large-scale murder of the Jewish population, had been brought about solely by Germans.

POGROMS AND COLLABORATION

Since the early stages of the war against the Soviet Union, non-Germans—in a kind of tacit division of labor—participated in anti-Jewish violence to a significant extent. The scope of their involvement ranged from assistance in identifying, persecuting, and ghettoizing Jews to the carrying out of pogroms, “cleansing measures,” or other acts of physical violence. The perpetrators were resident gentiles, collaborators brought in from other areas, and soldiers or policemen of countries allied with or controlled by the Reich.116 Heydrich’s order to the Einsatzgruppen to foster “self-cleansing measures” by the local population against communists and Jews indicates that these crimes would not have been committed without Operation Barbarossa.117 Thus, German policy is key to the understanding of non-German involvement. It is also evident that some gentiles, despite the risks involved, provided vital support for Jews who tried to escape from Nazi persecution.118 Yet the question remains concerning the extent to which non-German assistance was important for shaping anti-Jewish policy at this stage in the process and later on.

Lithuania—home to the largest concentration of Jews in the Baltic and the site of early instances of mass murder—poses this question with particular urgency. Here, unlike in other parts of the occupied Soviet Union, with the exception of Latvia and western Ukraine, locals were from the beginning of German rule until its end deeply involved in the murder of the Jews. At the outbreak of the war and in some cases before the arrival of German troops, pogroms swept the country. In the city of Kaunas, according to reports by EK 3, some 3,800 Jews lost their lives in these outbursts.119 Neighboring Latvia, which had been completely occupied by the Wehrmacht by July 10, was the site of similar scenes, though on a smaller scale. In Riga, the capital, an auxiliary police unit under nationalist Viktors Arajs in agreement with Einsatzgruppe A killed several hundred communists, Jews, and other “undesirable” persons by mid-July.120 In western Ukraine (Volhynia and Eastern Galicia annexed by the Soviet Union in September 1939) approximately 24,000 Jews were murdered by Ukrainians; by the end of July, pogroms supported by the Germans had claimed the lives of at least 5,000 Jews in the Eastern Galician capital Lwow alone.121 Some of the most notorious killing units of the Holocaust operated far beyond the borders of their home countries. Auxiliary police units from Latvia and Lithuania helped to carry out the mass murder of Jews deep in Belorussia, while Ukrainians (and other ethnic groups) trained in Trawniki near Lublin served as guards for German death and concentration camps.122 Clearly, this astonishing degree of involvement in murder was not merely the result of German instigation; there were other, indigenous factors at work.

German preinvasion memoranda indicate that stereotypes about “the east” and its inhabitants allowed a certain degree of differentiation in regard to the relative qualities of different despised ethnic groups. For the dual purpose of exploitation and domination, Russians were seen, together with the Jews, as least desirable, while Ukrainians and the peoples of the Baltic States fared comparatively better. Hitler applied a similar hierarchy but, because of his political grand design regarding “the east,” was unwilling to grant preferential treatment to Ukrainians, Latvians, and others regarded as racially inferior. At the same time, German policy exploited ethnic rivalries and residual local anti-Semitism, as well as national ambitions, to facilitate gaining control of the occupied territory. Using these factors helped implement the vision Hitler expressed during the meeting on July 16, 1941, of cutting up “the gigantic cake” for easier German consumption.123

The absence of any sincere desire on the part of politicians in Berlin to foster non-German self-determination did not deter nationalist groups from the Baltic States and Ukraine from seeking the assistance of the Reich against Moscow. Following the annexation of their countries by the Soviet Union in 1939/40, scores of political refugees left Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and western Ukraine, sometimes using the opportunities created by the resettlement of ethnic Germans agreed upon by Berlin and the Kremlin.124 Members of the respective security services had special reasons to escape before the Soviet NKVD took control. Pranas Lukys, who had worked for the Lithuanian secret police (Saugumas) and after the war was Böhme’s codefendant in the West German “Einsatzkommando Tilsit” trial, was one of them. The available evidence, sketchy as it is, given the absence of thorough research on the activities of Baltic émigrés in Nazi Germany, suggests that Lukys’s career was not an exception. Having crossed the border together with some fifty other secret policemen, he was interned in a camp near Tilsit. Preinvasion reports by the Stapostelle Tilsit prove that the Germans were aware of the potential usefulness of these Lithuanians for the pending war against the Soviet Union. The Tilsit office sent Lukys and some other Saugumas men to an assignment with the Security Police near Lublin in the General Government, where they stayed until their transfer to Memel in spring 1941. From there, one night before the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, they were sent across the border to Lithuania to prepare subversive activities against the Red Army.125

In preparation for the attack, the Reich provided nationalists and anti-Bolshevists not only with a safe haven but also with opportunities to organize and direct propaganda efforts and to plan for the future following the Soviet withdrawal. One of the most well-known Lithuanian expatriates in Berlin, Kazys Skirpa, formed the Lithuanian Activists Front (LAF), which tried to transcend the longtime division separating the two bourgeois camps, the right-wing sympathizers of former president Antanas Smetona and the profascist “Iron Wolf” movement.126 Skirpa and his men exploited anti-Jewish feeling and claimed that Jews formed the backbone of the Bolshevist system and thus had caused the loss of Lithuania’s national independence. In a leaflet drafted in March 1941, the LAF gave instructions to its sympathizers across the border for the anticipated “hour of Lithuania’s liberation”:

Local uprising must be started in the enslaved cities, towns, and villages of Lithuania or, to put it more exactly, all power must be seized the moment the war begins. Local Communists and other traitors of Lithuania must be arrested at once, so that they may not escape just punishment for their crimes (The traitor will be pardoned only provided he proves beyond doubt that he has killed one Jew at least). . . . Already today inform the Jews that their fate has been decided upon. So that those who can had better get out of Lithuania now, to avoid unnecessary victims.127

In the weeks before the beginning of Operation Barbarossa, the LAF intensified its propaganda efforts with German help by infiltrating anti-Soviet agitators, distributing propaganda leaflets, or broadcasting radio messages across the border. Because of its limited number of members, especially from among the prewar Lithuanian establishment, the LAF was more a symbol of anticommunism than a key political player. Even before the Wehrmacht had occupied the country, Lithuanian units of the Red Army, most notably its 297th Territorial Corps in the city of Kaunas, staged a mutiny that hastened the Soviet retreat. Following the Red Army’s withdrawal, provisional military commanders and other Lithuanian agencies, including a provisional government in Kaunas, emerged to stake a claim for future self-rule if not independence.128 Insurgents of the LAF and other anti-Bolshevists played an important role in the instigation of pogroms.

Compared with the reluctance of Germans to address their own crimes, the great number of German testimonies and photographs depicting pogrom scenes in the east is surprising. Most notorious are images and statements by bystanders on the killings that took place in Kaunas between June 23 and 28, 1941. “I became witness,” a colonel stated in the late 1950s regarding the clubbing to death of male “civilians” by a young Lithuanian, “to probably the most frightful event that I had seen during the course of two world wars.” A corporal from a bakers’ company described a similar scene in Kaunas: “Why these Jews were being beaten to death I did not find out. At that time I had not formulated my own thoughts about the persecution of the Jews because I had not yet heard anything about it. The bystanders were almost exclusively German soldiers, who were watching the cruel incident out of curiosity.”129

Public scenes like these, in an area controlled by the Reich and with Germans as onlookers, were unprecedented. In Lithuania and elsewhere, Wehrmacht officers watched with a mixture of approval and apprehension. On July 1, 1941, the war diary of the 1st Mountain Division in Lwow noted that during a meeting of unit commanders shots could be heard from the direction of the GPU prison as part of a “full-scale pogrom against Jews and Russians” (regelrechten Juden- und Russenpogrom) instigated by Ukrainians.130 In Drohobycz, the local military commander observed “terror and lynch justice against the Jews”; the overall number of victims remained undetermined.131 Even the most high-ranking military officers declared themselves unable to interfere. Field Marshal von Leeb, the commander of Army Group North, wrote in his diary about the killings in Kaunas that “the only thing to do is to keep clear of them.” (Es bleibt nur übrig, dass man sich fernhält.)132

Some representatives of the occupying power openly applauded such outbreaks of mass violence. From Lwow, where pogroms had been raging for days, the secret military police reported on July 7 that “the fanatic mood was transmitted to our Ukrainian translators,” who had been recruited from nationalistic circles. According to the report, these Ukrainians “were of the opinion that every Jew should be clubbed to death immediately.” (Ferner waren sie der Meinung, dass jeder Jude sofort erschlagen werden müsse.)133 In a number of places, Germans did not just look on favorably but actively participated in locally instigated atrocities against Jews, Russians, and communists, thus contributing to the radicalization of German measures.134 In the long run, however, “spontaneous” violence by locals had to be channeled into organized crime. Since Heydrich’s order of June 29 provided little assistance for solving practical problems, Security Police officers in the field looked for guidance to the Wehrmacht, which had already started to make systematic use of non-German collaborators.

From Kaunas, Erich Ehrlinger of EK 1b reported to the RSHA on July 1, 1941, that the local anti-Soviet “partisans” had been disarmed a couple of days earlier on order of the German military commander. To ensure their future availability, Ehrlinger continued, the Wehrmacht Feldkommandant had created an auxiliary police unit consisting of five companies from among the ranks of reliable collaborators. Ehrlinger presented this measure as at least partly motivated by social considerations: the auxiliary policemen had no jobs, were “without any means, partly without housing.” The entire economic situation, including food supply for the local population, remained unclear. Of the two companies subordinated to EK 1b, one was guarding “the Jewish concentration camp created in Kaunas—Fort VII [one of the old fortifications of the city]—and carries out the executions.” Several army units had adopted different policies in Lithuania. For Ehrlinger, the most pressing task was to solve the “Lithuanian question according to uniform guidelines.” (“Im Interesse der deutschen Ostraumpolitik ist es aber unbedingt notwendig, dass die litauische Frage nach einheitlichen Richtlinien gelöst wird.”)135

The speedy integration of local pogroms into the emerging pattern of German policy makes it extremely difficult to identify their specific driving forces. As can be seen from events in Kaunas and Lwow, considerations for German interests determined local actions at least indirectly. Once units of the Wehrmacht or the Security Police had started adopting a more long-term strategy, German preponderance became much more visible. As most of the available contemporary documentation originated from the Einsatzgruppen, it is not surprising that other agencies—German as well as non-German—appear less important.136 Nevertheless, the reports from Security Police units provide essential information on the local setting and the mix of factors. Obviously, the perpetrators of early mass killings did not restrict their activities to Jews; and even where Jews were targeted exclusively, anti-Semitism seems not to have been the sole motive. On the same day that the “partisans” of Kaunas were disarmed, the Lithuanian provisional military commander issued an appeal to the population to beware of “raging Russians and Jewish communists.”137 In nearby Vilnius, Lithuanian aggression focused on Poles, the largest ethnic group in the city.138