The development of UCG in Australia

L. Walker Phoenix Energy Ltd., Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Abstract

Australian interest in UCG commenced in the second half of the 1970s following an assessment of work undertaken in the former Soviet Union and the United States and its application to the conversion of Australia's large underground coal resources into power and chemical products. The focus from the outset was the commercialization of known technology, which led to a number of UCG demonstration projects and development plans in the period 2000–10 funded from stock exchange listings. These programs were largely located in Queensland but were halted as a result of the state government's review and subsequent banning of the technology, which has impacted on UCG development nationally. This chapter discusses the progressive development and shutdown of these projects and the factors required for successful commercial development of the technology in the future.

Keywords

Underground coal gasification; Australia; Syngas; Chinchilla; Bloodwood Creek; Kingaroy; Groundwater; Coal seam gas; UCG policy; Environmental approval; UCG commercial development

6.1 UCG origins (1970s to mid-1980s)

The origins for the development of UCG technology in Australia can be firmly attributed to Ian Stewart, professor of chemical engineering at the University of Newcastle in New South Wales. Over the period from 1974 to 1982, Professor Stewart, with the support of a series of government research grants, undertook a detailed review of the state-of-the-art of the technology, its potential application to Australian coals, and the benefits likely to accrue from its adoption nationally.

The work undertaken over this period is described in a report (Stewart, 1984). It consisted of a number of elements:

• Visits and inspections to a number of locations in the United States, Europe, and the former Soviet Union (FSU) in 1976.

• Attendance and presentation of papers to underground coal gasification conferences in the United States (1976, 1979, and 1981) and in Europe (1979).

• Laboratory experimentation to improve the operation of borehole injection systems (Stewart et al., 1981).

• A brief review of the potential for application of UCG technology to coals in a number of states in Australia.

The report concluded that “in situ gasification of deep seams of hard coal should be commenced now to provide for future power and syngas requirements.” It recommended that field development work be undertaken using known techniques, with a recommendation that this work be done either at the existing Leigh Creek coal mine site in South Australia or in the lower Hunter Valley region of New South Wales.

Late in 1981, Ian Shedden, founder of Shedden Pacific Pty Ltd, a consulting engineering company based in Melbourne, was requested by CSR Ltd to undertake a prefeasibility study for in situ gasification of the Anna lignite coal deposit in South Australia, with a review of the then-current aboveground coal gasification technologies as an alternative option (Shedden Pacific, 1981). Professor Stewart was commissioned to review the basic data for the deposit and provide a preliminary design for the UCG process and the suitability of the technology for the process. The coal analysis indicated a moisture content of 54%, an ash content of 10.9%, and a specific energy of 9.9 MJ/kg. No detail of the site geology was included, although Stewart's evaluation assumed a coal seam thickness of 4 m at a depth of 75 m and drew heavily on information gained from a review of the UCG programs in the FSU and the United States.

Shedden Pacific used this work to complete an engineering and economic study for use of the gas to generate 250 MW of power or as an alternative 2000–2500 tonnes/year of methanol (Shedden Pacific, 1983). The study concluded that “in situ gasification of the Anna deposit appears feasible and warrants further investigation.” No further work on this project was reported.

Perhaps, as a follow-on from this work and in response to the developing recommendations ultimately published in Stewart's, 1984 report (Stewart, 1984), Shedden Pacific was requested by the Department of Mines and Energy (DME) and the Electricity Trust of South Australia (ETSA) to undertake a prefeasibility study of the application of UCG technology to the Leigh Creek coal deposit. The study was undertaken with the assistance of Professor Stewart (UCG process design) and Dr. Len Walker, a geotechnical engineer with consulting engineering firm Golder Associates Pty Ltd (geology, rock mechanics, and groundwater evaluation).

Lobe B in the Leigh Creek coal deposit was estimated to contain a reserve of some 120 million tonnes of coal, with seams ranging in thickness from 8 to 13 m at depths projected to 400 m and with the coal analysis indicating a moisture content of around 26%, an ash content of 20%, and a specific energy of 14–15 MJ/kg.

The project report (Shedden Pacific, 1983) describes the UCG process design, the gas and wastewater treatment, and the design of 2 × 35 MW gas turbines for power generation, with provision for expansion to 250 MW. Indicative levelized power costs were estimated to be around 3 c/kWh for the larger plant, significantly below the cost of alternative energy sources. The report recommended a project development program involving field geotechnical work, gas turbine evaluation for combustion of low calorific fuels, and initial demonstration of gas production prior to design and construction of the 70 MW plant.

Although a further field investigation program was undertaken (Dames and Moore, 1996) to assess in more detail the impacts of the geotechnical properties of the rocks and the permeability of the coal seam, the project was not developed further due to the lack of financial support. Despite significant efforts by the various parties, no further funding for the project was obtained, and it was shelved.

By the middle of the 1980s, the oil price had dropped from a high in April 1980 of US$40/bbl to a low of US$10.25 in March 1986, thus reducing the incentive to develop alternative energy sources, causing severe cuts in government funding for research programs, and limiting any immediate further interest in the technology in Australia. However, the work undertaken had a clear focus on commercial project development using existing knowledge rather than the undertaking of new research activities. This approach was to be taken up in later years, supported by commercial rather than government funding, as detailed in following sections.

6.2 The quiet period (mid-1980s to 1999)

The lack of funding for the Leigh Creek project effectively ended the prospect for further development of the UCG work initiated by Professor Stewart. However, the authors of the report (Stewart, Shedden, and Walker) maintained their interest in the technology and, over the following years, reviewed potential opportunities for applying it in Australia.

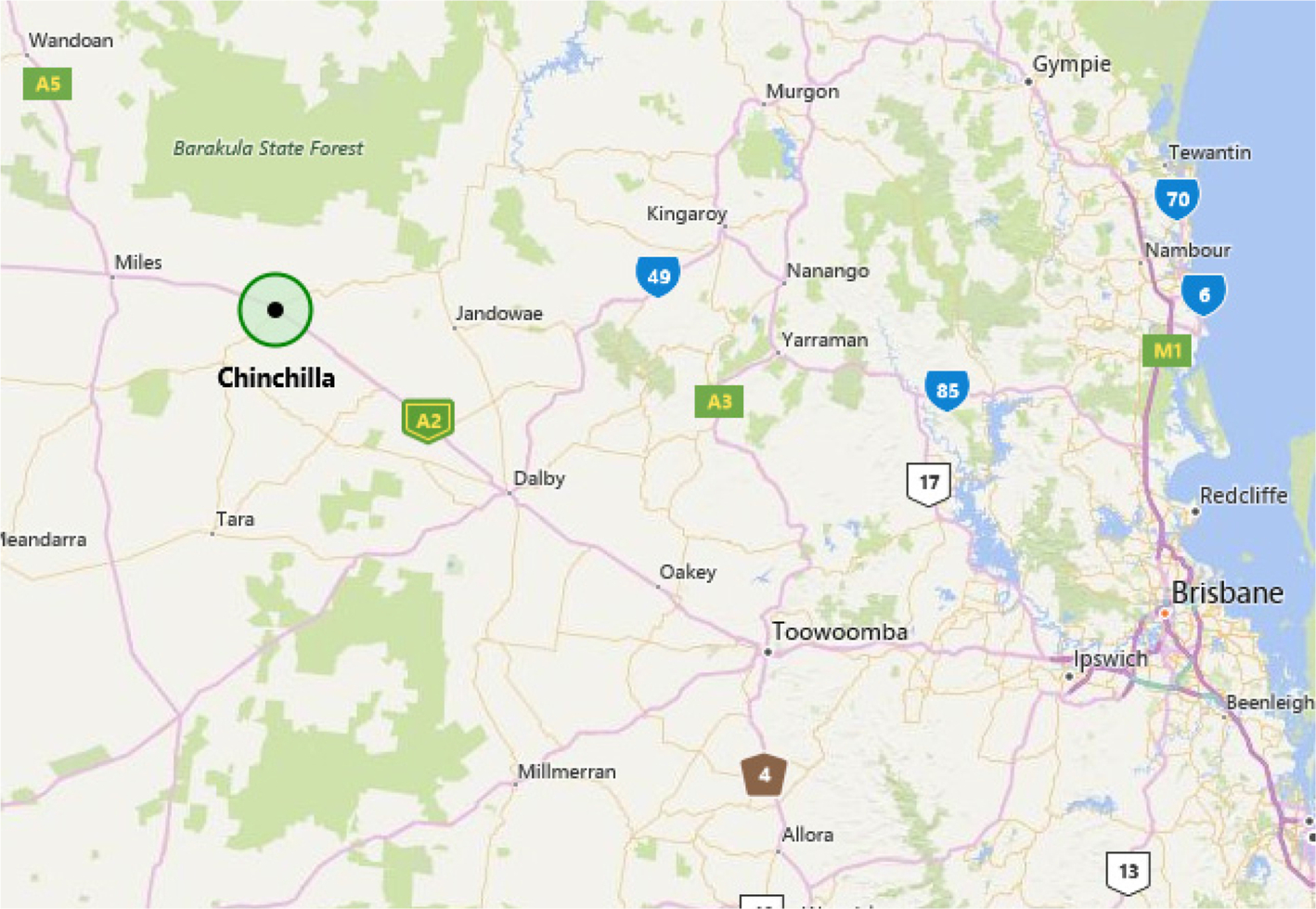

By 1988, Walker had assessed the prospects for developing UCG projects in both Queensland (Surat coal basin) and New South Wales (Gunnedah coal basin) due to the abundance of coal available and the lack of any interest in underground mining of deep coal deposits in these basins. The focus eventually turned to Queensland as a result of greater interest from the relevant government department. As a result, in 1988, he applied for coal exploration licenses in the Ipswich and Chinchilla areas. The former was a coal-mining area some 50 km from Brisbane, with an old power station nearby (Swanbank) being considered for shutdown. The Chinchilla area was selected because of the likely large size of a prospective underground coal deposit, sufficient for a major, long-term project. The location of Chinchilla is shown in Fig. 6.1.

Late that year, Walker commissioned a preliminary study into the potential for supplying UCG syngas to the Swanbank station and adapting the existing coal burner system to receive the gas (Kinhill Engineers, 1989). The study was undertaken with the support of CS Energy, the owner of the power station, and concluded that electricity could be generated and supplied to the existing grid at a competitive price. Despite these efforts, no funding could be raised for developing the project, and the coal applications were dropped.

The lack of interest in financial support for UCG development continued for the rest of the decade, although by the end of 1990 the oil price had increased back above US$20, with a peak of US$40. These fluctuations, and the previous work undertaken on the commercial prospects for UCG in Australia, helped to maintain an underlying interest in the technology (Walker et al., 1993). During this time, Walker had a number of meetings with US companies involved in the successful Rocky Mountain 1 test in Wyoming. As a result of this continuing interest, he founded Linc Energy Ltd in October 1996 with the purpose of acquiring rights to coal in Queensland (following his initial efforts in 1988) and commercializing the technology in that state. Linc Energy lodged applications for three exploration permits for coal (EPCs) in Queensland, one each near Chinchilla and Ipswich west of Brisbane and one in the Galilee basin 300 km south of Townsville (Walker, 1999).

At the time that Linc Energy was founded, the international activity in UCG technology involved the effective closure of the development effort in the United States and the undertaking of a demonstration pilot project in Spain (the El Tremedal project). Both these activities had adopted the so-called CRIP technology involving the use of long deviated horizontal wells in the coal seam for both oxidant injection and for product gas recovery, which was proposed as the “way of the future” for the technology.

This situation changed in February 1997, when contact was made between Walker and Dr. Michael Blinderman, a UCG technologist from the FSU program. Dr. Blinderman had been at the center of the Soviet National UCG program and worked at the Angren (Uzbekistan) UCG plant and at the Yuzhno-Abinsk UCG plant in Siberia. It turned out that in 1994, Dr. Blinderman and his colleagues established a UCG technology company, Ergo Exergy Technologies (Ergo Exergy), which by 1997 was providing UCG expertise to several projects then under development in the United States, India, and New Zealand. Walker and Blinderman reached an agreement to develop a commercial UCG project in Australia, with Walker selecting a suitable coal deposit and organizing the commercial structure for the venture and Blinderman with Ergo Exergy providing the UCG technology based on their previous practical experience.

As a result of his review of historical UCG experience in the FSU, summarized in a US research report (Gregg et al., 1976), Walker was convinced of clear predominance of the FSU experience over work done in other countries and saw great value in visiting an FSU UCG plant and witnessing its performance. On Walker's request, Walker and Blinderman visited the Angren (Uzbekistan) UCG facility in May 1997—the first of three such trips to cement ongoing relationships between the parties. As a result of this visit and a review of past literature, it was agreed that the use of the Ergo Exergy technology, stemming from the vast R&D efforts in the FSU and the experiences of commercial-scale operations at the Angren plant, was the most effective means of developing a commercial UCG operation in Australia.

With the support of Ergo Exergy, Linc Energy in 1997 undertook a joint preliminary feasibility study with Austa Energy for a power station near Ipswich in Queensland fueled by UCG gas (Austa Energy and Linc Energy, 1997). Austa Energy was at the time a Queensland Government-owned company providing engineering services and creating business development opportunities for the state government. The report concluded that “power can be produced from this gas at least 25% cheaper than from a coal-fired power station costed on a comparable basis” and that the cost of the gas production was “less than half the expected cost of natural gas.” In preparation of the report and after reviewing the geology data and visiting Linc Energy coal tenements in Ipswitch and Surat basin, Ergo Exergy experts recommended the site near Chinchilla for initial UCG development in Australia in clear preference to the Ipswitch location.

With this report as confirmation of the commercial viability of the UCG process for power generation, Linc Energy sought a listing on the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) and on 30 June 1998 lodged with the Australian Securities Commission a prospectus for the raising of A$4 million to undertake “a pilot burn on EPC(A)-635 (at Chinchilla) as phase 1 of a power generation project on the site” (Linc Energy, 1998). The Linc Energy directors at the time were Walker, Blinderman, and Mike Ahern, expremier of Queensland appointed as chairman. In August 1998, the prospectus was withdrawn as a result of the poor investment climate at the time. As a result, Linc Energy commenced negotiations with a number of companies with an existing commercial interest in power generation, ultimately signing a joint venture agreement in June 1999 with CS Energy, one of the Queensland Government-owned power-generating companies (Walker, 1999). The joint venture proposed an initial pilot burn at the Chinchilla site, to be followed by installation of a small-scale power plant of about 40 MW.

At about this time, CSIRO was developing an interest in UCG and in March 1999 held a workshop to discuss its potential in Australia. The workshop was led by Burl Davis, experienced in the UCG demonstration projects undertaken in the United States that were funded by the US Department of Energy. Following this workshop, a 6-year UCG research program was initiated by CSIRO focused on various aspects of the technology and site selection (Beath et al., 2000, 2003). It was during this time that Linc Energy initiated the first Australian demonstration of UCG technology at Chinchilla.

6.3 Initial success—Linc Energy at Chinchilla (1999–2004)

The joint venture between Linc Energy and CS Energy commenced in June 1999 and focused on the production of syngas as the first phase in the development of a 67 MWe IGCC project (Walker et al., 2001). The project was funded by CS Energy with the assistance of a research grant from the Australian government.

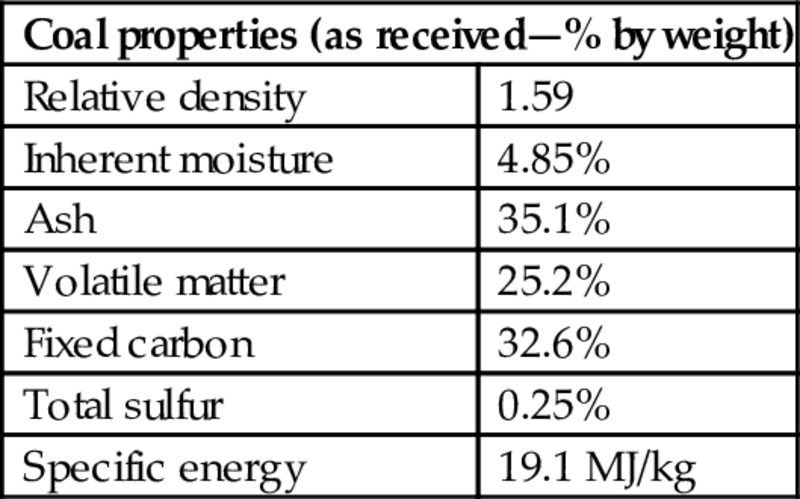

The project site involved the development of the MacAlister coal seam 10 m thick at a depth of 120 m. A site characterization program was initiated in June 1999 and concluded with UCG-specific in situ testing in September 1999. Properties of the coal are set out in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1

Chinchilla coal properties

| Moisture % | 6.8 |

| Ash % | 19.3 |

| Volatile % | 40.0 |

| Fixed carbon % | 33.9 |

| Total % | 100.0 |

| Total moisture | 10.1 |

| Relative density | 1.50 |

| SE MJ/kg | 23.0 |

Construction, commissioning, operations, controlled shutdown, and postgasification monitoring of gasification panel at Chinchilla were based on the Ergo Exergy UCG technology and effected under direct supervision of Ergo Exergy UCG experts led by Dr. Blinderman. The UCG facility used air injection and reverse combustion linking to connect nine process wells to the gasifier over the period of operation (Blinderman and Fidler, 2003). First gas production was achieved on 26 December 1999, and the plant (Fig. 6.2) operated continuously until April 2002, with the gas being flared over this period. The process produced syngas at a calorific value of about 5 MJ/Nm3, at a pressure of 10 barg and temperature up to 300°C.

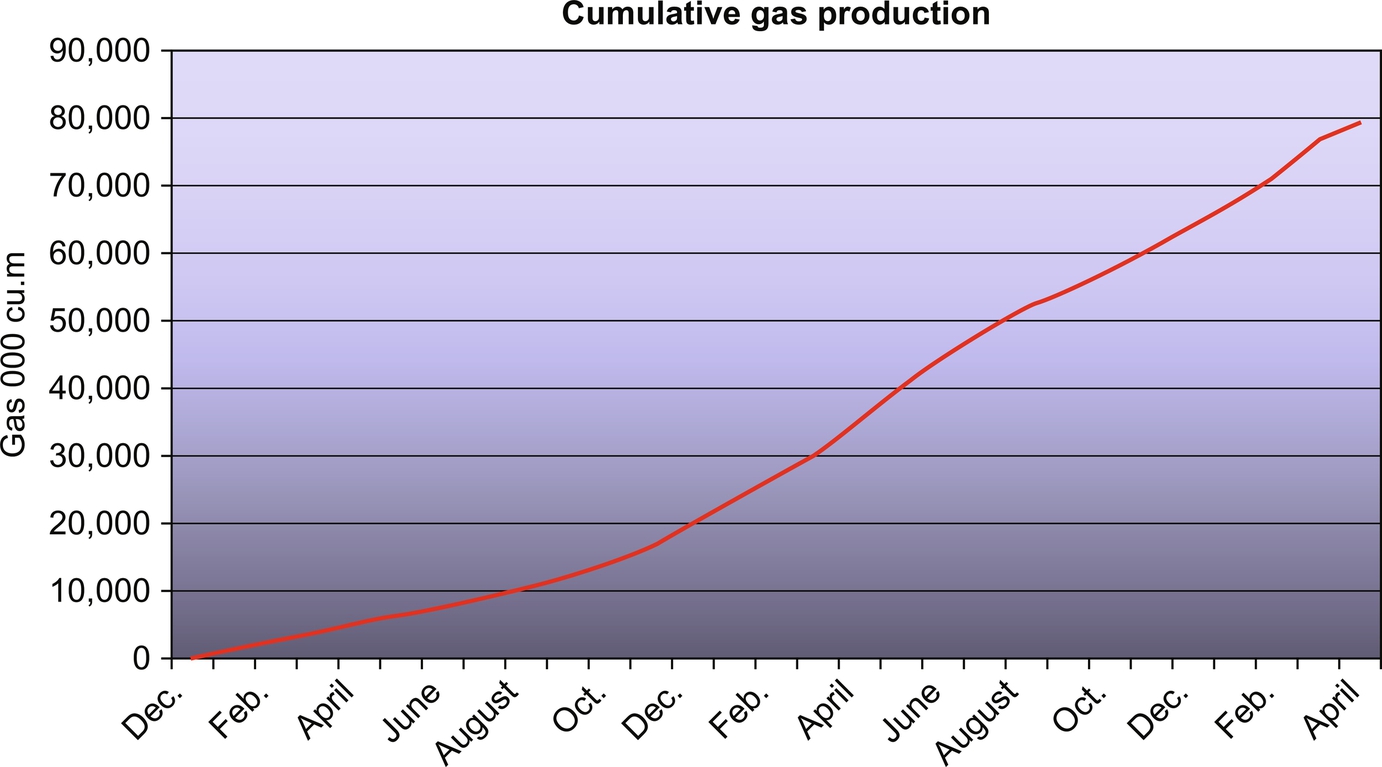

Continuous gas production was achieved over the period of operations (Fig. 6.3), with some 35,000 tonnes of coal being gasified and with no evidence of environmental impact (Blinderman and Fidler, 2003). However, a controlled shutdown of operations was initiated in April 2002 (Blinderman and Jones, 2002), largely as a result of limited project finance being available following the terrorist attacks in the United States in September 2011.

As part of the project operation and ultimate shutdown, considerable attention was paid to the interaction between site geology and hydrogeology, described in detail by Blinderman and Fidler (2003). The factors most relevant to the UCG operations included the following:

• Overlying alluvium 10–20 m deep, generally dry over the UCG operating site, with a groundwater level 30–35 m belowground level.

• A known aquifer system in the Hutton Sandstone, at a depth of approximately 600–650 m.

• A significant fault some 300 m to the northwest of the operating area, with a throw estimated at 40 m, disrupting the hydraulic continuity of the coal seam in that direction.

• Coal seam thickness of 10 m at a depth of 120 m, dipping at 1°–5° to the south-southeast.

• Methane present in the coal seam, requiring monitoring bores to be sealed at the surface.

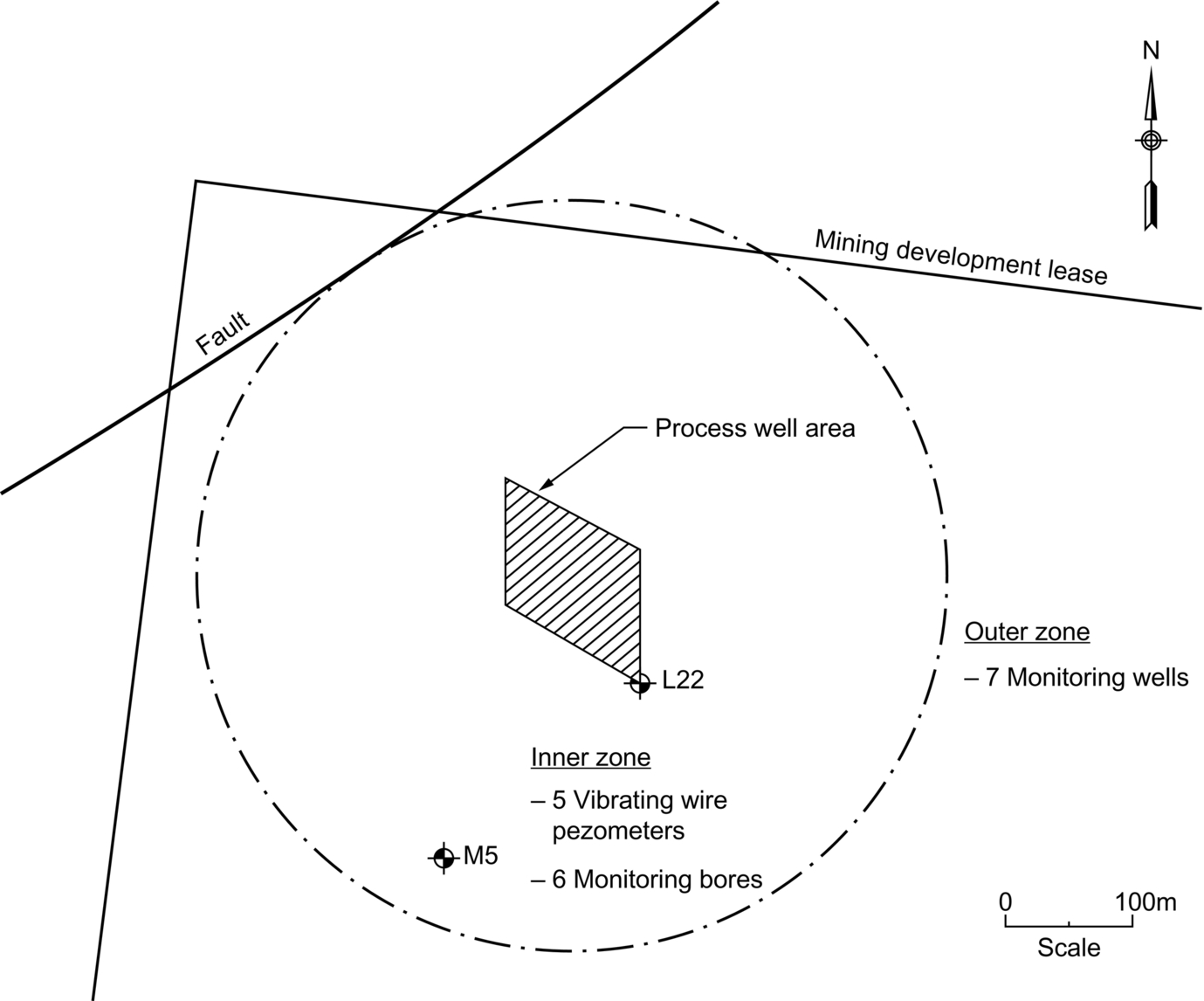

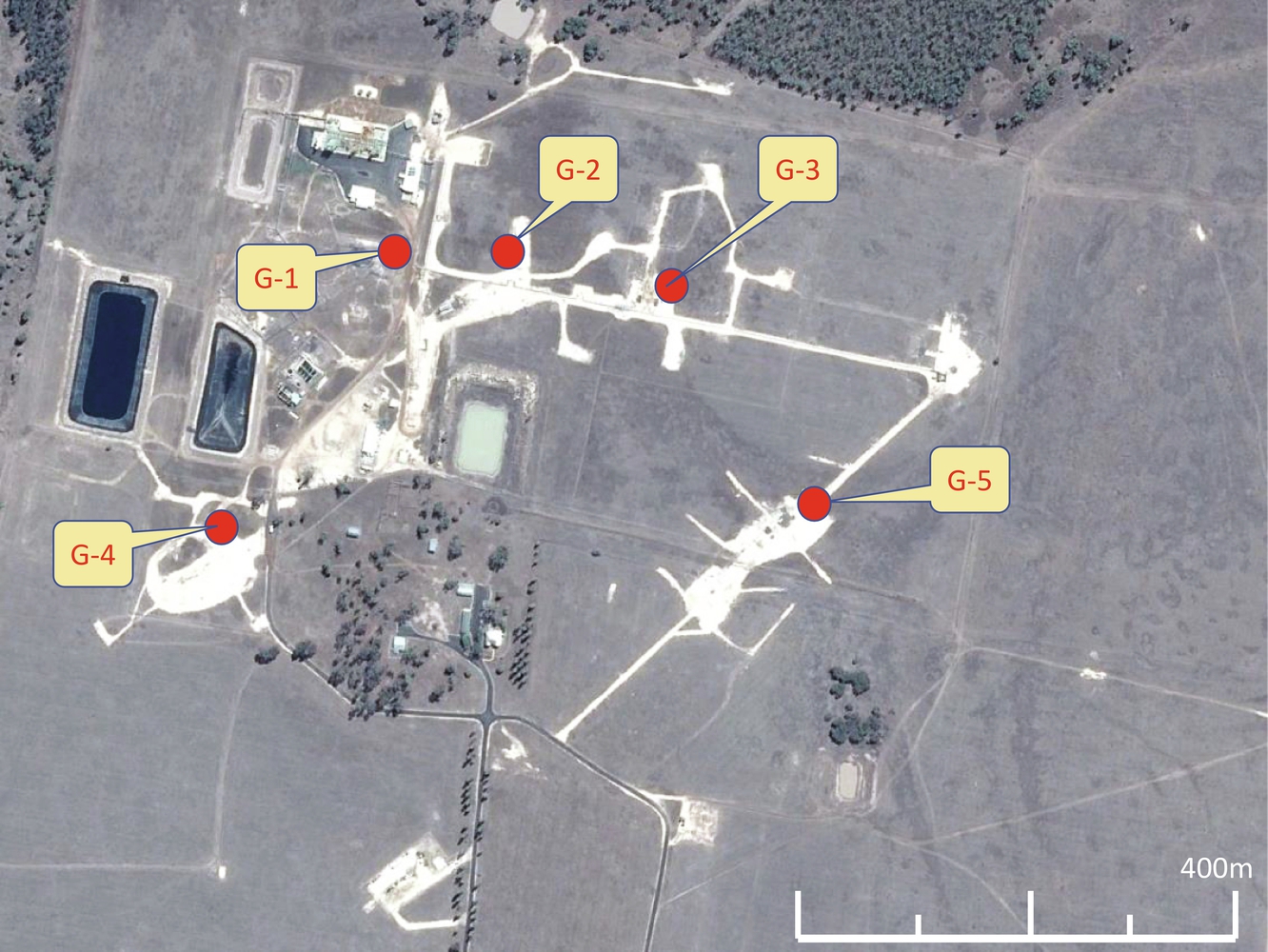

The general site layout is shown in Fig. 6.4.

Groundwater measurements indicated a hydraulic gradient of 0.0015 toward the southwest, i.e., subparallel to the fault shown in Fig. 6.4. Groundwater quality was generally poor, with total dissolved solids in the range of 1400–3900 mg/L. Pump testing to determine the permeability of the coal seam was not possible because of the impact of methane gas, with packer testing giving a wide range from 4 × 10− 5 to 2 × 10− 9 m/s, with a significant anisotropy being evident, and maximum permeability along the northeast/southwest axis. Testing showed high gas conductivity in the coal seam ranging between 0.3 and 1.5 darcy.

As indicated in Fig. 6.4, five vibrating wire piezometers (VWPs) and seven groundwater monitoring bores were located within an inner zone of about 300 m radius, and seven monitoring bores were outside this zone, three of which were installed prior to the cessation of air injection in the shutdown process. Blinderman and Fidler (2003) noted that a hydraulic connection existed between the process well area and monitoring bore M5 some 200 m away, confirming the high permeability in this direction and the effective extent of the gasifier area.

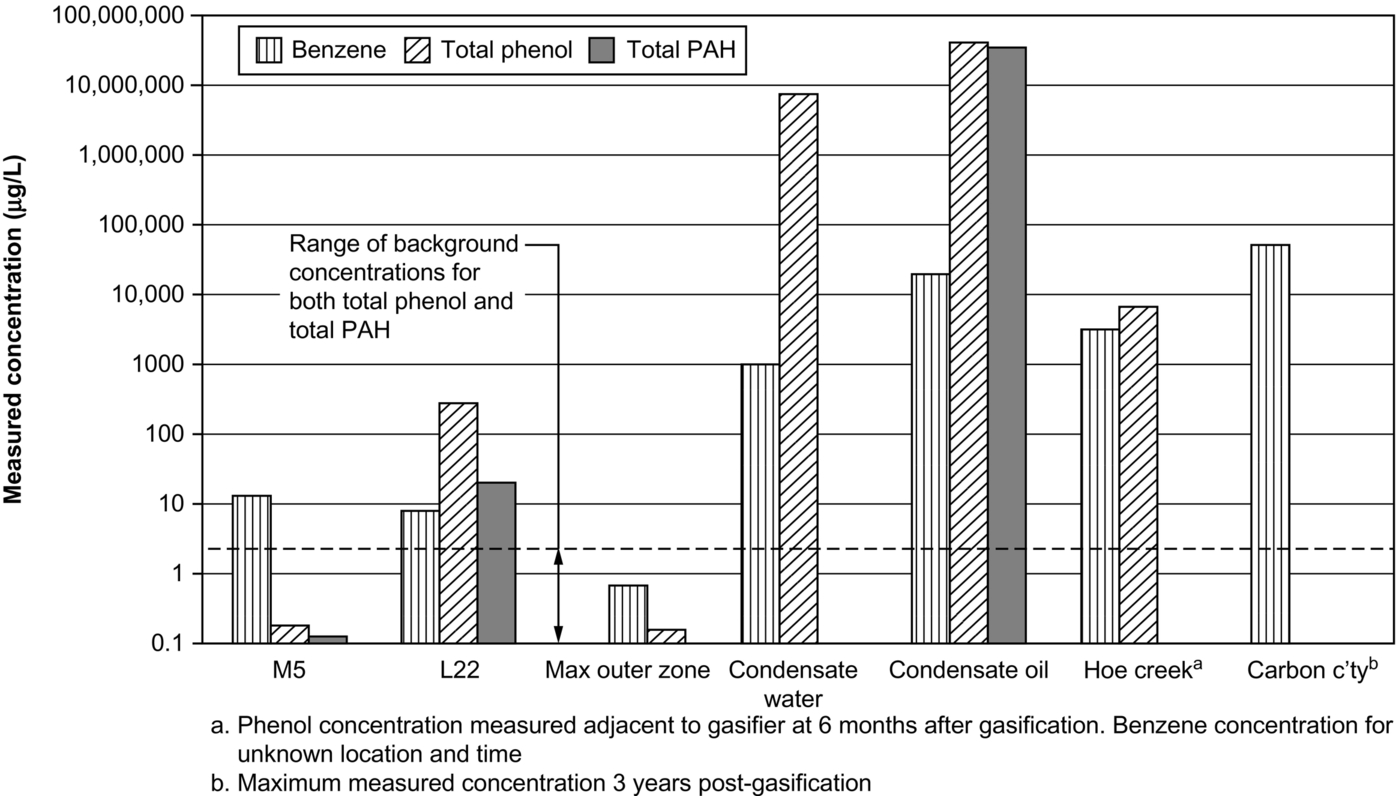

Groundwater samples were taking during the shutdown period from monitoring bore M5 and from the process well L22 located in Fig. 6.4 to assess the impact of the shutdown process. The results from these measurements are shown in Fig. 6.5 and were compared by Blinderman and Fidler (2003) with results from measurements of the condensate water and from two other projects in the United States (Hoe Creek and Carbon County). The levels detected at the end of shutdown were below the advisory levels published by the USEPA and well below the levels at the US sites. The authors emphasized the need for proper operation of the cavity to ensure potential groundwater contaminants are removed in the condensate water.

As a result of its financing of the Chinchilla project, CS Energy had effective ownership and financial control of Linc Energy and the Chinchilla project. Late in 2001, CS Energy requested a review of the technical and economic viability of UCG technology for power generation, which was completed in April 2002 (Blinderman and Spero, 2002). Although the report resulted in positive recommendations for the Chinchilla project, CS Energy chose to withdraw from the joint venture in the absence of alternative project funding. It elected in May 2002 to close down the existing project, which led to the controlled shutdown process described above, and to offer its interest in the company for sale. Despite expressions of interest from a number of parties, a sale was not achieved until early 2004. The CS Energy shares were purchased by Peter Bond, a coal-mining entrepreneur, the Linc Energy board was restructured, and discussions about reestablishing the Chinchilla project followed.

In March 2006, the company issued a prospectus for raising A$22 million and listing on the ASX (Linc Energy, 2006a). The funds were raised, and the company commenced trading on 8 May 2006. The prospectus described the company's business plan to use the UCG process to “deliver on its business to turn coal deposits into commercial quantities of diesel and jet fuels.” In November 2006, with Ergo Exergy's termination of involvement with the Linc Energy as its technology provider, Linc Energy announced the signing of a UCG technology agreement with the Skochinsky Institute in Moscow (Linc Energy, 2006b).

Following the initial success of the Linc Energy project at Chinchilla (1999–2004), its successful listing of on the ASX, and its proposal to produce commercial quantities of liquid fuels, interest in UCG technology in Australia expanded. Over this period, the oil price accelerated past US$40/bbl toward $100/bbl, reinforcing the potential for commercial production of syngas using the UCG process, with its economic advantages over the alternative of surface gasification.

As a result of these factors, corporate interest in adopting UCG technology to develop commercial projects widened, with ASX listings as a focus for funding, and a range of potential end products being promoted. However, available information on these activities has been generally restricted to corporate presentations and ASX announcements rather than formal reviewed publications in professional journals. The reviews that follow below draw largely on this material that, by its nature, presents a preferred corporate perspective rather than a critical and technically substantial appreciation of project activity.

6.4 Rapid progress—Three active projects and many followers (2006–11)

6.4.1 The three active projects

6.4.1.1 Linc Energy

In September 2007, Linc Energy announced (Linc Energy, 2007a) that it had commenced producing UCG gas from a new field (subsequently referred to as gasifier 2) and in October that year (Linc Energy, 2007b) announced its purchase of a controlling interest in Yerostigas, the owner and operator of the UCG gas project at Angren in Uzbekistan, the largest of the UCG projects developed in the FSU. It also announced (Linc Energy, 2007c) the fabrication at Chinchilla of a demonstration gas-to-liquid (GTL) plant designed to convert the UCG syngas produced into liquid fuels.

Over the following 4 years, Linc Energy undertook the development of a succession of gasifiers represented as providing progressive improvements to the design of the UCG process. In July 2008, the company announced (Linc Energy, 2008a) it had completed the development of gasifier 3 and was finalizing testing of the GTL demonstration plant (Fig. 6.6). Subsequently, in October that year, the company announced its first production of liquid fuels from UCG syngas (Linc Energy, 2008b).

In March 2009, Linc announced the design of gasifier 4 to produce UCG syngas at a commercial rate of 5 PJ/annum (Linc Energy, 2009a). In November 2009, the company announced that this gasifier was to be commissioned by the year's end and that the design of gasifier 5 was also in progress (Linc Energy, 2009b). Gasifier 4 was reported to be in operation in February 2010, with gasifier 5 being planned to be developed on the company's new project in the Arckaringa Basin in South Australia (Linc Energy, 2010a). In May 2010, Linc announced the use of oxygen injection for the first time, being applied to gasifier 4 (Linc Energy, 2010b). Gasifier 5 was ultimately ignited at the Chinchilla site in 2011 and according to Linc Energy operated for 2 years over 2012/2013, testing both air and oxygen injection (Linc Energy, 2013a).

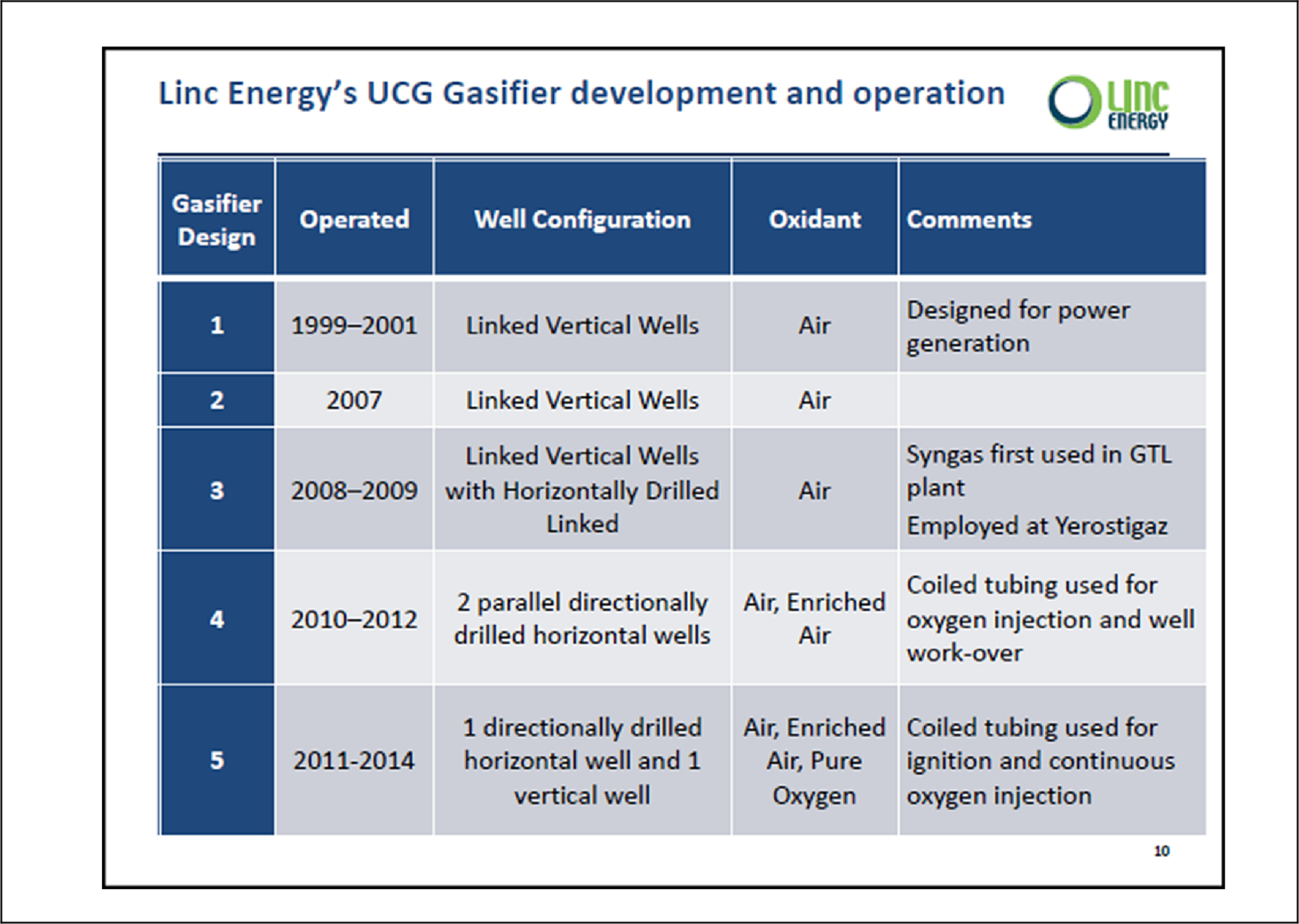

A summary of the sequence of Linc Energy's gasifier construction and operation as provided by the company (Linc Energy, 2013a) is shown in Table 6.2, and the location of the five gasifiers developed on the Chinchilla site are shown in Fig. 6.7 (Linc Energy, 2013a).

Linc Energy presented gasifier 5 as containing the design and implementation procedures that it would use to advance to commercial development. The design involved connecting one deviated in-seam injection well, installed using a coil tube rig, with a vertical production well 880 m away, as indicated in Fig. 6.8. Commercial production was to be achieved by replicating this system.

The performance of this gasifier was summarized (Linc Energy, 2013a) as follows:

• Start-up on 22 October 2011.

• Shutdown on 4 November 2013.

• 730 days on stream.

Twelve successive retractions of the injection well were completed, using both air blown and oxygen blown injection, with enrichment levels varying from 21 (air) to 100% (oxygen). Calorific values for the product gas up to 6.2 MJ/Nm3 were achieved for air injection and up to 10.2 MJ/Nm3 for oxygen injection. During operations, cavity growth models were constructed, and validation using field instrumentation was claimed, although no detailed presentation of these data has been published.

During the period of operation of the gasifier sequence described above, Linc Energy also developed a wide range of interests in the broader oil and gas industry, and further progress of the proposed GTL plant at Chinchilla stalled after shutdown of gasifier 5. This lack of further progress was also accentuated by the declining confidence in support for UCG technology exhibited by the Queensland Government.

It is difficult to assess the actual progress of Linc Energy's development of gasifiers 2–5 from their published information. However, in 2014, Linc Energy was charged under Queensland's Environmental Protection Act with five counts of wilfully and unlawfully causing serious environmental harm. The charges were subjected to a hearing in the Magistrates Court of Queensland in October/November 2015, and the decision to commit the company to trial was handed down on 11 March 2016 (Queensland Government, 2016a,b).

From the evidence presented at the hearing, it is clear that

• Pressures of between 28 and 48 bar were used in gasifier 2.

• Gases escaped “directly to the surface” from gasifier 2.

• Pockets of syngas were intersected in the overburden during drilling for gasifier 3.

• Gasifier 4 exhibited gas escapes from monitoring bores and bubbling of gas at the surface.

• Gas escapes from monitoring bores over the operational period of gasifier 5.

• Gasification pressure in gasifiers 2–5 consistently exceeded hydrostatic groundwater pressure.

From the above, it is evident that Linc Energy had technical difficulties in managing process operations at the Chinchilla site throughout the operation of gasifiers 2–5, which may at least partly explain the number of gasifiers developed. The apparent communication of gas across the site would appear to be consistent with the high horizontal permeabilities reported by Blinderman and Fidler (2003).

6.4.1.2 Carbon Energy

The program of research work undertaken by CSIRO early in the 2000s was led by Dr. Cliff Mallett and culminated in the formation of a wholly owned company (Coal Gas Corporation Pty Ltd-CGC) and its acquisition of three coal leases in the Surat Basin covering an area of 2375 km2. In July 2006, a company listed on the ASX (Metex Pty Ltd) announced (Carbon Energy, 2006) that it had taken a 50% interest in CGC and provided $2.5 million for the company to progress “identifying and developing a suitable underground coal deposit for demonstration and development of the UCG process” and that “the initial trial would target coal seams at greater than 400 m depth.”

Exploration drilling on the leases commenced in January 2007, and in May that year, the company announced (Carbon Energy, 2007a) that it was completing the design of its demonstration plant, due for construction from September and had secured an exclusive alliance with Burl Davis (the United States) “to assist in the detailed design and operation of UCG.” Davis had led the workshop on UCG organized by CSIRO in March 1999. By this time, CGC had been renamed Carbon Energy Ltd, and in November 2007, Metex purchased the remaining shares in the company, and Mallett joined the Carbon Energy board (Carbon Energy, 2007b). In July 2008, Metex changed its name to Carbon Energy Ltd (Carbon Energy, 2008a).

Carbon Energy had chosen a site at Bloodwood Creek in the Surat Basin containing a coal deposit in the same geological sequence and with similar properties to that utilized by Linc Energy in Chinchilla, with an operating depth of 200 m. The company elected to use the basic concept of the CRIP system, involving two parallel in-seam boreholes 850 m long and 30 m apart, with a vertical well for ignition as was developed in the United States in the 1980s. However, a modification to the injection well retraction system was incorporated into the design, referred to as the “key seam” technology.

Completion of the installation of the first panel was announced in August 2008 (Carbon Energy, 2008b), and ignition and initial gas production followed on October 8. However, several months later, the company reported a blockage in the injection well that required a “reconfiguration of the well layout” (Carbon Energy, 2008c). It is understood that with the horizontal injection well blocked, this involved the use of supplementary vertical wells for injection. The first 100 days of the trial was completed in February 2009 (Carbon Energy, 2009), and planning commenced for a commercial-scale UCG panel (panel 2) to be constructed with the installation of a small power plant (5 MW) to be later expanded to 20 MW (Carbon Energy, 2010a). Ultimately, the first panel was abandoned (Carbon Energy, 2010b), as it was considered “not cost-effective” to continue with its remediation. A delay in construction of the new panel occurred when the government in July 2010 required an environmental evaluation report from the company on the discharge of surface water from the test site (Carbon Energy, 2010c). This issue was resolved early in 2011, and panel 2 was ultimately installed and commissioned in March 2011 (Carbon Energy, 2011a).

The location of the two panels on the site is shown in Fig. 6.9 (Carbon Energy, 2013), with a horizontal separation of about 60 m. Published test data on gas composition from the second panel are shown in Table 6.3 for both air and oxygen injection. Subsequently, Carbon Energy advised in October 2011 of its first production of electricity from gas engines using the UCG syngas as a fuel (Carbon Energy, 2011b), but that further expansion to 5 MW and export of power to the grid system needed a modification to their existing environmental approvals. Panel 2 operated for 577 days and gasified 12,745 tonnes of coal, which corresponds to less than 2500 Nm3/h average gas production flow rate.

Table 6.3

Carbon Energy panel 2 gas composition—air and oxygen/steam blown

| Primary constituents—dry gas basis | Average—mole % oxygen/steam blown | Average—mole % air blown |

| Hydrogen (H2) | 26.66 | 20.94 |

| Methane (CH4) | 19.06 | 8.60 |

| Carbon monoxide (CO) | 7.13 | 2.56 |

| Ethane (C2H6) | 1.42 | 0.54 |

| Carbon dioxide (CO2) | 45.21 | 21.63 |

| Nitrogen (N2) | 0.28 | 44.67 |

| Average calorific value—LHV (MJ/Sm3) | 10.94 | 5.71 |

| Average calorific value—HHV (MJ/Sm3) | 12.24 | 6.46 |

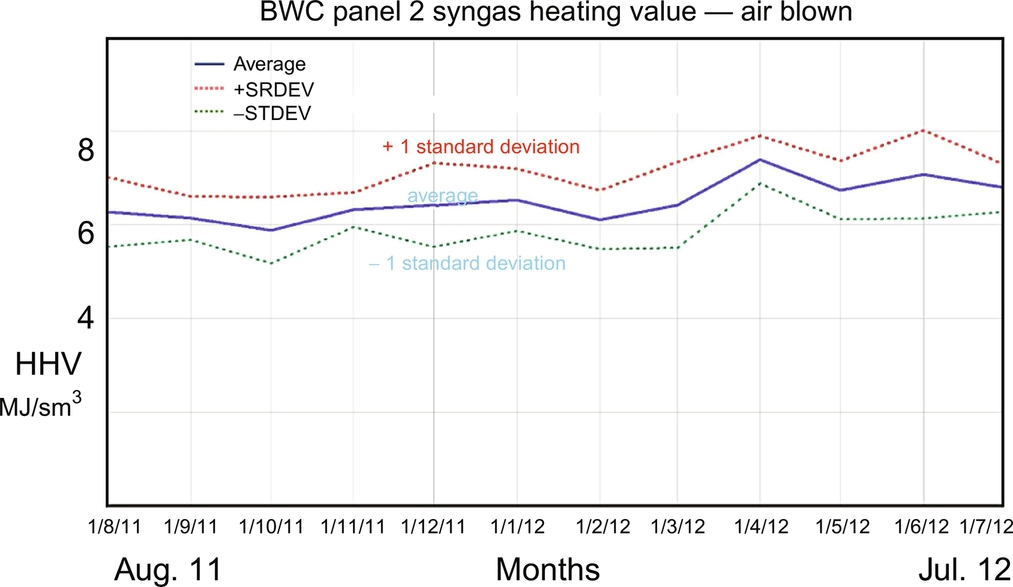

Fig. 6.10 presents the calorific value (higher heating value) for a continuous 12-month operating period of panel 2 using air injection.

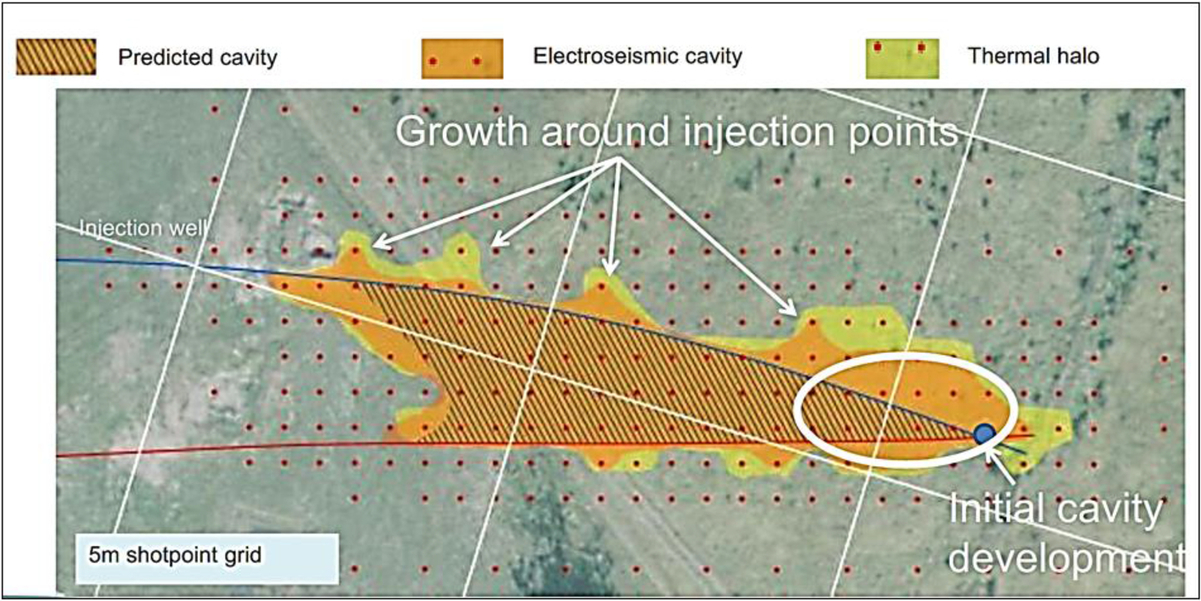

As part of the operation of panel 2, Carbon Energy undertook a survey of the extent of the gasification cavity using thermal and electroseismic techniques. The results from this survey are presented in Fig. 6.11, with the scale indicated by the 5 m spacing of the electroseismic shot points. The data showed the capability of surface measurement techniques to define the extent of the underground cavity created, although the results have not been verified by extensive postgasification drilling into the cavity.

Further development of panel 2 and Carbon Energy's Bloodwood Creek project overall were delayed pending a review of UCG technology commissioned by the Queensland Government (refer to Section 6.7.3). Regardless of the findings of this report, the government placed a ban on further UCG development in April 2016 and ordered Carbon Energy to decommission UCG operations and rehabilitate the site.

The Carbon Energy test at Bloodwood Creek was undertaken on the same Surat Basin coal seam as that undertaken by Linc Energy at Chinchilla. It is of interest to compare the published data from these two tests, gasifier 1 at Chinchilla (using vertical wells and shutdown in 2002) with panel 2 at Bloodwood Creek (using the modified CRIP system). The results are shown in Table 6.4.

Table 6.4

Test data comparison

| Item | Chinchilla (gasifier 1) | Bloodwood Creek (panel 2) |

| Total coal gasified | 35,000 tonnes | 12,750 tonnes |

| Operating period | 850 days Air injection | 577 days Air injection |

| CV of product gas (LHV) | 5.7 MJ/m3 | 5.6 MJ/m3 |

| Max. coal usage | 49 t/day | 21 t/day |

| Max. energy prodn. ratea | 750 GJ/day | 325 GJ/day |

| Gas production rate | 5470 m3/h | 2420 m3/h |

| Energy produced/tonne coal | 15.0 GJ/t | 14.7 GJ/t |

| Panel area tested | 2300 m2 | 850 m2 |

a Note that a 30 MW power plant will require syngas at a rate of about 6600 GJ/day.

Data in the table confirm that the Chinchilla test, when compared with the Bloodwood Creek test:

• Gasified nearly three times as much coal, with an effective panel area three times the size.

• Showed twice the average daily coal usage rate and more than twice the maximum gas production rate.

The average daily gas production rate in 1965 at the Angren plant in the FSU is reported (Gregg et al., 1976) at 12,900 GJ/day, approximately 17 times the rate for the Chinchilla test and 40 times the rate at the Bloodwood Creek test.

The above data confirm the continuing relevance of the large-scale UCG process procedures developed in the FSU while also illustrating the considerable expansion in gas production rates required to achieve a scale suitable for commercial development.

6.4.1.3 Cougar Energy

Cougar Energy was formed by Dr. Len Walker as an ASX listed company in October 2006, some 4 years after closure of the first successful Linc Energy demonstration at Chinchilla. The company acquired the rights to develop a UCG project on a coal deposit near Kingaroy, 150 km northeast of Brisbane in Queensland, and on additional potential deep coal deposits in the Surat and Bowen basins. The UCG technology was provided under a license agreement by Ergo Exergy. The coal seam selected for development at the Kingaroy site was the Kunioon seam, which ranged in thickness from 7 to 17 m, at depths from 60 to 206 m. The coal properties are summarized in Table 6.5.

Table 6.5

Kunioon coal seam properties

| Coal properties (as received—% by weight) | |

| Relative density | 1.59 |

| Inherent moisture | 4.85% |

| Ash | 35.1% |

| Volatile matter | 25.2% |

| Fixed carbon | 32.6% |

| Total sulfur | 0.25% |

| Specific energy | 19.1 MJ/kg |

Following resource definition and site characterization work, development of the Kingaroy project was planned in the following stages:

• Ignition and syngas production, gas cleaning, and flaring for a period of 6–12 months.

• Power generation by gas engines or gas turbine up to 30 MW.

• Expansion of power generation to 200 MW and then 400 MW.

This phased program was not greatly different from that contemplated for the Chinchilla site; however, it was more clearly defined at an early stage in Cougar Energy's life, and with the technical experience gained from the past demonstration and the availability of progressive funding from the ASX listing, it was considered to be realistic. Significant emphasis was also placed on the design of a pilot gas-cleaning plant, sufficient to provide an output gas composition suitable for direct combustion in existing commercial gas turbines.

The site layout plan for the project is shown in Fig. 6.12, and the gas treatment plant is shown in Fig. 6.13.

A detailed discussion of the company's progress at Kingaroy is contained elsewhere in another chapter; however, the time line of activity can be summarized as follows (Walker, 2014):

• Resource drilling completed—June 2008.

• Ignition and first gas production—15 March 2010.

• Air injection halted due to casing blockage—20 March 2010.

• Evidence of 2 ppb benzene in one monitoring bore—21 May 2010.

• Discussion of results with government officials—30 June 2010.

• New production wells drilled—early July 2010.

• False benzene test result of 82 ppb submitted to government—13 July 2010.

• Confirmation of false result submitted to government—14 July 2010.

• Shutdown notice received—17 July 2010.

• Environmental Evaluation reports prepared—from August to December 2010.

• Permanent shutdown and rehabilitation notice received—July 2011.

In total, the Kingaroy UCG facility effectively operated for only 5 days and gasified approximately 20 tonnes of coal. Even so, Kingaroy project has produced technically and environmentally valuable results discussed in a separate chapter of this book.

6.4.2 The followers

Over the period from 2006 to 2011, there was considerable UCG activity with demonstration pilot burns being undertaken by Linc Energy, Carbon Energy, and Cougar Energy. These three companies raised funds as a result of being listed on the ASX, and each had specific plans for developing significant commercial projects involving the production of diesel and jet fuels (Linc Energy), ammonia and methanol (Carbon Energy), and power (Cougar Energy). These project plans were underpinned by an oil price consistently around US$100/bbl.

Although the Queensland Government early in 2009 had approved only the three companies to demonstrate UCG technology (refer to Section 6.6), a number of other companies listed on the ASX saw the opportunity to promote their interest in UCG technology with a view to following on from the expected likely successful adoption of the technology in that state. The activities of these companies are summarized below, some of which included proposals that would have stretched the existing state of knowledge of the technology. However, they illustrate the wide spread of interest in UCG technology at the time, particularly over the period from 2008 to 2011 and the potential that existed for this to be translated into a national commercial industry in Australia. The information presented is again obtained from company presentations and from announcements made to the ASX.

6.4.2.1 Liberty Resources (ASX Code:LBY, now CNW)

In September 2008, Liberty Resources (LBY), an existing ASX listed company, announced (Liberty Resources, 2008a) that it had signed an option agreement to purchase companies holding for exploration permits for coal applications (EPCAs) in Queensland covering a total area of 64,000 km2 “potentially suitable for underground coal gasification.” On 11 December 2008, the company announced (Liberty Resources, 2008b) an inferred resource on its Galilee basin coal permit of 338 million tonnes of coal to “fast track UCG investigations and site selections.” The option was exercised, and the purchase completed in April 2009 (Liberty Resources, 2009a).

In July 2009, LBY entered into a heads of agreement (HOA) with Carbon Energy to form a joint venture to develop a UCG project on its Galilee basin permit (Liberty Resources, 2009b) and a separate HOA with Clean Global Energy to undertake a similar project on its Surat Basin permits. It also announced “an exploration potential target of from 280 to 350 Bt (billion tonnes) of coal” on its coal permits based on a review of historic oil and gas well data. The company cemented its declared interest in UCG by joining the UCG partnership based in the United Kingdom in September 2009 (Liberty Resources, 2009c).

In June 2010, LBY reported (Liberty Resources, 2010a) the results of a scoping study into the economics of syngas production on one of its Queensland permits. The company also confirmed that it was unable to commence a pilot trial of the technology due to the limitations imposed by the Queensland Government's UCG policy. The company continued to focus on potential project analysis and, in October 2010, declared (Liberty Resources, 2010b) a focus on using UCG syngas for developing large-scale urea and fertilizer production. This project work continued through 2011–13, with no apparent progress on the development of a UCG gas production trial and an increasing interest by the company in conventional coal opportunities. In October 2014, LBY announced (Liberty Resources, 2014) a change of business for the company, with confirmation of disposal of all its mining interests in April 2015 (Liberty Resources, 2015).

6.4.2.2 Clean Global Energy (ASX Code:CGV, now CTR)

Clean Global Energy (CGV) was formed initially as a private company to develop UCG on its coal leases in Queensland, using experience gained from the Spanish UCG trial in 1997. In April 2009 (Clean Global Energy, 2009a), it entered into a HOA to be taken over by a listed company and so acquire an ASX listing. A formal share sale agreement was signed in June 2009, and the transaction was completed in October 2009 (Clean Global Energy, 2009b). At that time, the company announced HOAs with Carbon Energy in Queensland and companies in Victoria and China as part of its plan to develop commercial projects in these areas as well as on its own coal leases in Queensland. By the end of 2010, the company had also identified UCG project prospects in the United States and India and established an initial resource for UCG development on its Queensland permits (Clean Global Energy, 2010).

However, following board changes in May 2011, CGV relinquished its UCG interests in China and the United States and in November announced (Clean Global Energy, 2011) the complete withdrawal of its interest in UCG, to focus on conventional coal mining and other energy activities.

6.4.2.3 Eneabba Gas (ASX Code:ENB)

In October 2008, Eneabba Gas (ENB), an ASX listed company, announced (Eneabba Gas, 2008) that it was in discussion with several providers of UCG technology in relation to applying the process to its coal leases near Geraldton in the Perth basin in Western Australia. The company was involved in gas supply contracts and had proposed a 168 MW power station near its leases to meet demand from nearby iron ore mines. In May 2009, ENB signed an HOA with Carbon Energy by which Carbon would acquire certain coal leases, apply its UCG technology and produce syngas for supply to ENB's proposed power station (Eneabba Gas, 2009). Following work by both parties during the year, the HOA expired in December 2009.

ENB's focus on UCG was confirmed in March 2010 when it joined the UCG Association based in London. Subsequently, in April 2010 (Eneabba Gas, 2010), it entered into an MOU with Cougar Energy for development of a UCG project on its permits, to be followed by the signing of a binding term sheet in early June that year. Cougar Energy's progress on the project was however greatly hampered by the events at its Kingaroy plant in Queensland, and the agreement was terminated in February 2011 (Eneabba Gas, 2011).

ENB maintained a declared interest in applying UCG to its coal leases until July 2015, when it advised (Eneabba Gas, 2015) that this activity would be discontinued and that the company would focus on conventional gas exploration.

6.4.2.4 Metrocoal (ASX Code:MTE, now MMI)

In May 2006, Metallica Minerals (MLM—ASX Code, MLM) announced an agreement with Cougar Energy (prior to its listing on the ASX) to investigate the feasibility of applying UCG to its coal tenements in Queensland, including one at Kingaroy that became the site of Cougar Energy's UCG project (Metallica Minerals, 2006). Cougar commenced drilling at Kingaroy early in 2007 and completed acquisition of the coal tenement in November 2008.

In May 2008, MLM announced (Metallica Minerals, 2008) that it would commence drilling to assess UCG potential on its other coal tenements to enable it “to join the emerging Australian UCG sector.” By January 2009, MLM was aggressively pursuing a drilling campaign in the Surat Basin to establish a potential UCG project, with a proposal to obtain a separate listing for its subsidiary coal company (Metrocoal). This ASX listing for MTE was completed in December 2009 (Metallica Minerals, 2009).

During 2010/2011, MTE maintained an expressed interest in UCG but by the end of 2011 was confirming its preferred interest in conventional underground mining as a result of the declining support for UCG from the Queensland Government and also subsequently an added interest in bauxite mining.

6.4.2.5 Central Petroleum (ASX Code:CTP)

In June 2011, Central Petroleum (CTP) announced (Central Petroleum, 2011) a plan to develop its coal leases in the Pedirka basin in the Northern Territory using UCG technology. It provided a consultant's report concluding that a total “exploration target potential” of between 730 and 890 billion tonnes of coal existed on CTP's petroleum and mineral leases, above a depth of 1000 m. The shallowest intersection shown from existing drilling logs was at about 400 m depth. CTP proposed to call for expressions of interest in developing an integrated UCG facility to initially produce 60,000 bpd of liquid fuels.

This proposal was still being pursued when a change in board control occurred in April 2012 (Central Petroleum, 2012), and the emphasis of the company turned back to conventional oil and gas exploration. The UCG proposal was not pursued subsequently.

6.4.2.6 Wildhorse Energy (ASX Code:WHE, now SO4)

In September 2009, Wildhorse Energy (WHE), an Australian company listed on the ASX and active in uranium exploration in Poland, announced (Wildhorse Energy, 2009) the acquisition of Peak Coal, a company with significant coal permits in Hungary and a plan to develop those assets using the UCG process. This acquisition was ultimately completed in February 2010, and the company engaged the services of a number of former employees of the Sasol group of companies to undertake the UCG development program.

Over the following years, the company undertook a range of studies for a UCG project on its licenses in Hungary, with no active field work being undertaken. In February 2014, it announced (Wildhorse Energy, 2014a) an agreement to sell its UCG assets to Linc Energy. In August 2014, Linc Energy withdrew from this agreement, and as a consequence, WHE relinquished all its interests in UCG as part of a company restructure announced in October 2014 (Wildhorse Energy, 2014b).

Although Australian-based, at no stage did WHE acquire any assets or express any interest in developing UCG technology in Australia.

6.4.3 Academic research

During the period of development of UCG projects in Australia, academic research efforts were undertaken in several Australian universities. A number of research projects in the University of Queensland were conducted in close cooperation with Ergo Exergy in support of the projects applying the ɛUCG technology, in particular, the Chinchilla UCG project (gasifier 1, 1999–2006) and the Majuba UCG project in South Africa.

A study of ash formation effects on ash leaching in the postgasification cavity focused on variation of residual ash leachability with changing physical condition of the ash sample (Jak, 2009). The combustion group at the University of Queensland led by Dr. A. Klimenko, working in close cooperation with Ergo Exergy and Dr. M. Blinderman, developed the theories for reverse and forward combustion linking, for flame propagation within the gasification zone in a channel and performed simulations of the gasification process (Blinderman and Klimenko, 2007; Blinderman et al., 2008a,b; Saulov et al., 2010; Chodankar et al., 2009). Exergy optimization of the linking process was considered as a part of this research, and theoretical results were compared with the data from field linking conducted under supervision of the Ergo Exergy technologists working at the Chinchilla UCG project (gasifier 1, 1999–2006).

A number of computational models for underground coal gasification were developed by Greg Perkins at the University of New South Wealth (Perkins, 2007, 2008). These models considered the heat and mass transport and incorporated evaluation of the cavity growth. The results of simulations were compared with the UCG trial in Centralia (the United States).

6.4.4 Summary of progress

By the end of 2009, there were six ASX listed companies actively pursuing UCG activities in Queensland and two others active in Western Australia and Hungary, respectively. The three main companies were also actively undertaking UCG gas production operations in the field in Queensland. This spread of activity at the time was probably unique in the recent history of the technology and gave considerable confidence to the belief that commercialization of the technology in Australia was imminent.

The essential contribution to this goal at the time can be summarized as follows:

• A number of active companies with a variety of objectives in adopting the technology.

• The use of private capital to pursue development, compared with previous international development almost exclusively relying on government research funding.

• The use of stock exchange listing to raise capital, spreading the investment risk among many individuals and investment funds, and taking advantage of market “excitement” for the technology to assist funding efforts.

The fact that the commercial objectives of none of these participants were achieved, despite the industry momentum at the time, requires careful analysis if a new generation of active UCG participants is not to suffer the same fate. The following analysis endeavors to highlight those factors impacting on successful commercial development, drawing on the experience obtained from UCG activities in Australia.

6.5 UCG and coal seam gas (CSG) interaction

To understand the factors involved in UCG development in Queensland, especially political ones, it is essential to review the competing interests of companies in that state involved in the coal seam gas (CSG) industry and those companies endeavoring to develop a commercial UCG industry.

A number of commercial facts are relevant to this understanding:

• The CSG industry in Queensland was led by a combination of large existing national oil and gas companies (Santos, Origin Energy) and a number of developing start-up companies (e.g., Arrow Energy, founded 1997, and Queensland Gas, founded 2000).

• The UCG industry in Queensland effectively commenced with the start-up of Linc Energy in 1996, and the successful Chinchilla demonstration from 1999 to 2002 that was shut down for lack of finance. A gap in activity of 4 years occurred before the follow-up stage led by the ASX listing of Linc Energy in 2006 and the formation of Carbon Energy and Cougar Energy in the same year.

• In the period from 2000 to 2006, major advances were being made in development of CSG production in the Surat Basin, using the same Walloon Coal measures as were being developed for UCG by Linc Energy during this time.

CSG exploration in the Surat Basin accelerated early in the 2000s, with Queensland Gas commencing in 2000 and Arrow Energy in 2001. Successful gas production was reported in July 2001 (Arrow Energy, 2001) from CSG wells in the Walloon Coal measures at 140 m (and shallower), that is, the same coal seams and depths being developed by Linc Energy at Chinchilla. Contracts for the supply of CSG to CS Energy (Linc Energy's JV partner) were signed with Santos in 2000, with Arrow Energy in 2001, and with Queensland Gas in 2002, as commercial quantities of gas were being developed.

The significance of these CSG developments at the time can be appreciated by reviewing a number of current proposals to recover CSG and pipe it to the eastern seaboard of Queensland for conversion to LNG for export. The proposals are very large in concept and cost and require very large supplies of gas. Company reports describe the large drilling campaigns necessary to meet the gas supply targets. For example, Arrow Energy announced (Arrow Energy, 2009) a Surat Basin Gas Project to supply gas to an LNG project on the east coast and gas for local power generation. The project was proposed to involve 1500 new CSG wells and gas pipelines estimated to cost $1.5 billion to transport the gas to central gas processing and water treatment facilities. Also, Queensland Gas reported (Queensland Gas, 2017) that the first phase of its Surat Basin project up to June 2015 had drilled 2520 wells and was currently drilling at a rate of 25 wells per month to develop a similar coal seam gas to LNG project. Santos and Origin Energy are involved in similar large-scale projects.

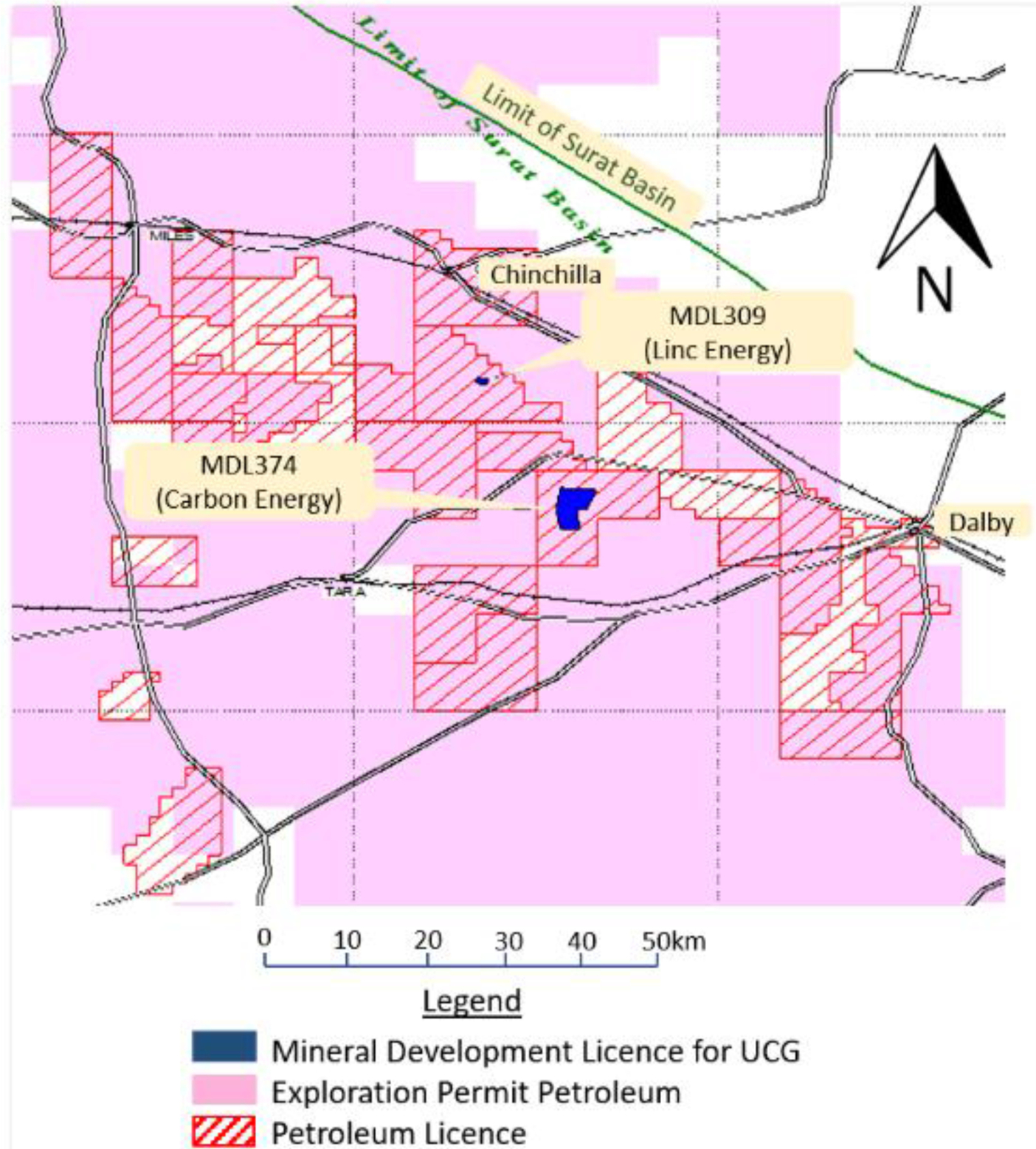

This progressive acceleration of exploration and production of CSG in the Surat Basin reinforced the potential conflict of interest between CSG developers, whose permits were granted under the Queensland Government Petroleum and Gas Act, and UCG developers, whose production permits, when granted, were to be granted under the Mines Act. By 2008/2009, when the Queensland Government introduced its UCG policy (discussed in the following section), the impact of the permit overlap issue at the time was clearly evident as shown in Fig. 6.14, which illustrates the permits granted in the Surat Basin at that time.

Fig. 6.14 shows that virtually the whole basin is covered by exploration permits for petroleum/gas, and most of the shallow coal (depth less than 400 m) is covered by petroleum production licenses (cross-hatched). The coal deposits dip to the southwest beyond 400 m depth, where they are less attractive for UCG development. The two granted mineral development licenses (MDL) for Linc Energy and Cougar Energy are shown in blue. These were confirmed by the government as solely for the purpose of UCG pilot trials, but not for commercial development, pending its consideration of the future of the technology in the state.

This unbalanced access to coal in the Surat Basin in favor of the coal seam gas industry is exacerbated by the area required for a fixed-energy output by the two technologies. CSG recovers any free or extractable methane gas from the coal, while UCG converts 70%–80% of the energy in the coal into gas and recovers any free methane from the oxygen depleted process cavity. It has been estimated (Carbon Energy, 2013) that from a defined area of coal, the UCG process will recover 20 times the energy from the coal deposit when compared with the CSG process.

A consequence of this comparison is that for a fixed-energy supply requirement, a CSG operator will require access to 20 times the area of land below which the coal seam exists. This requirement explains the large allocation of petroleum permit areas shown in Fig. 6.14 that are necessary to achieve an energy output that could be achieved from a much smaller UCG permit. It is also an indicator of the vast energy source potentially recoverable from the Surat Basin if the UCG technology were to be developed on a commercial basis.

Several technical operating factors also impact on the interaction between UCG and CSG interests. Of these, the most significant is the impact on the groundwater table. Because of its method of operation, the CSG process removes large volumes of water resulting in a significant, possibly long-term reduction in the groundwater table, and hence lowers the groundwater pressure in the coal seam at depth below the surface. It is this pressure reduction that allows the recovery of the methane. By contrast, the UCG process requires the maintenance of a significant water pressure head in the coal seam to balance (and exceed) the injected air or oxygen pressure in the cavity.

Side by side operations of the two technologies would therefore not be possible unless reliable predictions of CSG groundwater drawdown could be made with respect to pressure, to lateral extent and to fluctuations with time. This would be a difficult exercise given the variability of in situ permeability and its difficulty of prediction in advance of operational start-up or during CSG operations, which could place an adjacent UCG operation at environmental risk.

There would also be concern about undertaking UCG operations in an area where coal seams have been fully developed for CSG. The impact of CSG operations on the structure and permeability of both coal seams and overburden would cause considerable uncertainty for UCG operations, as would the risk of gas seepage paths being created around CSG well installations.

While it was not so evident in the late 2000s, it is clear with the advantage of hindsight that the aggressive development plans of a number of CSG companies and their effective control over the coal deposits through the permit system made any short-term development of the fledgling UCG industry in Queensland a doubtful proposition.

6.6 The Queensland Government UCG Policy

In the period from 1999 to 2008, the development of the UCG and CSG industries can be briefly summarized as follows:

• The Chinchilla test from 1999 to 2002 by Linc Energy provided evidence of successful production of UCG gas, followed by successful decommissioning.

• From 2000 onward, Linc Energy's partner CS Energy entered into a number of agreements to take CSG gas from existing development companies, withdrew from UCG development in 2002, and progressed its direct interest in developing CSG production.

• A strong interest in UCG was activated from 2006 with the renewed development plans of Linc Energy and the active development plans of Carbon Energy and Cougar Energy.

• The intervening period from 2002 to 2006 saw a rapid expansion in CSG exploration in the Surat Basin by a range of large and small companies.

Thus, by 2008, when commercial gas production from the three key UCG projects was imminent, the conflict between the technologies described in Section 6.5 was inevitably brought to a head.

The first indication of government action occurred in a press report responded to by Linc Energy (2008c), which quoted an unnamed source in the Department of Mines and Energy that “the government had no intention of granting production tenures for UCG for at least 3 years.” The minister subsequently issued a statement that the government would not grant production tenure for any technology that was untried and untested in Australian conditions, without specifically referring to a potential moratorium on UCG development.

On 18 February 2009, the Queensland Government released an underground coal gasification policy paper (Queensland Government, 2009), which stated that “the intention is to provide the UCG pilot projects with the opportunity to demonstrate the technical, environmental, and commercial viability of the technology.” No reference was made to the successful demonstration by Linc Energy from 1999 to 2002; hence, the UCG proponents were effectively asked to start again in satisfying the government as to the technology's potential.

The policy also included a number of other features:

• The appointment of an “independent scientific panel” (ISP) to assist in the preparation of a government report to enable it to “decide upon the future viability of the UCG industry in Queensland.”

• The formation of an industry consultative committee (ICC) comprising representatives from both the UCG and CSG industries, “responsible for considering and providing options to the government for the resolution of resource and technology conflicts.”

• No further UCG tenures were to be granted until the government decision on the future of the technology was made.

• “The findings of the government report on UCG will be presented to Cabinet in 2011/2012 and should the government report produce adverse findings on the UCG technology; ongoing constraint or even prohibition of UCG activities may be recommended.”

• In discussing overlapping UCG and CSG tenure, “the Minister for Natural Resources, Mines, and Energy, if asked to determine a coordination or preference decision between the developer of a CSG resource and the developer of a UCG resource, the decision will be made in favour of the CSG tenure holder under the P&G Act, so as to allow the CSG tenure to progress to production stage.”

This policy placed an effective moratorium on the issuing of UCG production tenures and achieved the objectives referred to in the press articles of August the previous year.

This UCG policy also had a number of implications for the small public listed companies proposing to develop UCG projects as their main objective:

• The future of the technology in Queensland was now in the hands of a political decision rather than determined by commercial development.

• The preference for CSG in any overlapping tenure dispute was compounded by the existing granted tenure positions shown in Fig. 6.14.

• The uncertainty generated by the policy was to have ongoing impacts on the financial resources of all UCG companies and their future capacity to raise funds from the public.

Despite these uncertainties, the three active companies received sufficient comfort from discussions with the government at the time to continue with their projects and to engage with both the ISP and with the ICC.

6.7 UCG development decay (2011–16)

6.7.1 Background

Progress of the three UCG companies actively developing projects in Queensland received a considerable setback with the announcement by the Queensland Government of its UCG policy. As a consequence of the policy, the plans of each company to rapidly progress from pilot plant to commercial operation were put on hold, with an uncertainty as to whether any project approvals would eventually be given.

With the passage of time and the events surrounding the decision to permanently shut down the Cougar Energy project in July 2011, the confidence that approval of commercial UCG projects in the state would be achieved progressively diminished.

The ISP (Queensland Government, 2013) released its report on the remaining two UCG pilot trials in June 2013 and concluded the following:

• Underground coal gasification could, in principle, be conducted in a manner that is acceptable socially and environmentally safe when compared to a wide range of other existing resource-using activities.

• … for commercial UCG operations in Queensland in practice first decommissioning must be demonstrated and then acceptable design for commercial operations must be achieved within an integrated risk-based framework.

While the first of these conclusions was welcomed as supporting commercial development, the second made it evident that the ISP was placing significant additional requirements on the companies to fully rehabilitate their existing pilots (i.e. they could not be continuously expanded into commercial operations), while requiring detailed design requirements for expansion to commercial size. The uncertainty of approval for commercial development therefore continued.

Eventually, all three operations in the state were terminated for reasons summarized below, with a flow-on effect for the rest of the embryonic UCG industry.

6.7.2 Linc Energy

In July 2013, Linc Energy announced (Linc Energy, 2013b) a positive response to the ISP report as an indication that the technology would be allowed to continue in Queensland, subject to successful evidence of cavity rehabilitation. In September 2013, the company confirmed (Linc Energy, 2013c) that it would be fully rehabilitating gasifier 3 to meet this part of the requirement of the ISP for commercial operations to be approved.

However, on 5 November 2013, the company announced (Linc Energy, 2010c) that it would be ceasing its operations at Chinchilla, decommissioning the site, and moving its operations offshore. The company gave its reason as “to date, the state has not provided the UCG industry with any material certainty or confidence capable of supporting commercial investment in UCG in Queensland.” The company concluded that it “must continue to progress its UCG business offshore to ensure the future deployment of UCG into regions such as Asia.” The company estimated the expenditure on its UCG program at A$300 million.

In the previous month, the company indicated it would be seeking to move its stock exchange listing from Australia to Singapore, and this move was successfully completed in mid-December 2013.

Subsequent to these events, the Queensland Government laid criminal charges against the company for wilfully and unlawfully causing serious environmental harm—four charges were laid in April 2014 and one in June 2014 (refer to Section 6.4.1.1). These charges were subject to a magistrate hearing in October/November 2015, and in March 2016, the company was formally committed for trial on all charges.

6.7.3 Carbon Energy

Carbon Energy operated its second UCG panel until late 2012, at which time it entered into the decommissioning phase as required by the Queensland Government as a condition for receiving approval for development of its commercial project. The company completed this procedure and provided a report to the government on 1 October 2014 (Carbon Energy, 2014).

The company announced in December 2014 that the review of this report by an independent consultant to the government had been completed and that the company anticipated receiving approval to proceed early in 2015. On a number of occasions through 2015, the company expressed the view that it had met all of the government's requirements in relation to rehabilitation of the UCG panels, had satisfied the requirements of the ISP, and in December 2015 (Carbon Energy, 2015) had its mineral development license renewed so that it could continue its UCG activities on the site. It was also in the process of discussion with the government about submitting an environmental impact statement for the construction of its commercial project.

On 16 April, 2016, without prior consultation with the company, the Queensland Government announced (Queensland Government, 2016a,b) a complete ban on UCG development in the state. Carbon Energy responded with an expression of surprise at the decision (Carbon Energy, 2016a), having satisfied all of the government's requirements and confirming that it would now take its technology offshore for development—specifically to China. The company estimated its UCG expenditure in Australia to have been A$150 million.

6.7.4 Cougar Energy

As summarized in Section 6.4.1.3 above, the Queensland Government had issued a shutdown notice on the company's operations in July 2010 and requested the company's response to a series of technical questions arising from the short-lived measurement of small concentrations of benzene in one monitoring bore. These queries were answered in a series of environmental evaluation reports submitted between August and December 2010. In October/November 2010, the company announced the progress of proposed project developments in China and Mongolia and opened an office in Beijing in May 2011.

Ultimately, the government issued a notice for permanent shutdown and rehabilitation of the Kingaroy site in July 2011. The company unsuccessfully endeavored to have this notice overturned and continued with its objective of developing UCG projects in the Asian region. This plan was eventually shelved following changes in the company board and management early in 2013, and the company removed UCG development from its corporate strategy. The investment in the technology was estimated to be A$30 million.

6.7.5 Other companies

The Queensland Government's decision to slow its decision-making on the future of UCG in that state also impacted on the attitude of other state governments, who were deferring their approaches to the technology pending the outcome of the activities in Queensland. Effectively, this created an uncertainty about the technology nationally in Australia.

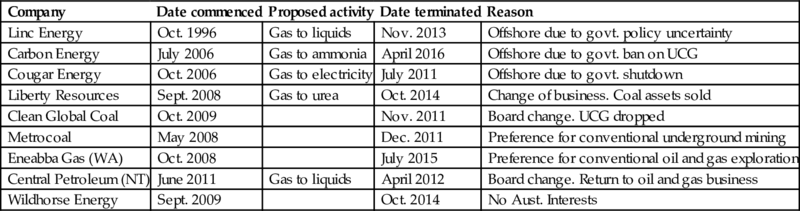

At the peak of activity in Australia in 2010/2011, in addition to the three government-approved UCG companies, six other ASX listed companies were proposing similar projects—three in Queensland—one each in Western Australia and the Northern Territory and one offshore in Europe. Each of these companies independently reviewed their involvement with the technology and withdrew their UCG plans as summarized in Table 6.6, by either taking its UCG development interest offshore or dropping its interest completely.

Table 6.6

UCG companies—withdrawal from Australian activity

| Company | Date commenced | Proposed activity | Date terminated | Reason |

| Linc Energy | Oct. 1996 | Gas to liquids | Nov. 2013 | Offshore due to govt. policy uncertainty |

| Carbon Energy | July 2006 | Gas to ammonia | April 2016 | Offshore due to govt. ban on UCG |

| Cougar Energy | Oct. 2006 | Gas to electricity | July 2011 | Offshore due to govt. shutdown |

| Liberty Resources | Sept. 2008 | Gas to urea | Oct. 2014 | Change of business. Coal assets sold |

| Clean Global Coal | Oct. 2009 | Nov. 2011 | Board change. UCG dropped | |

| Metrocoal | May 2008 | Dec. 2011 | Preference for conventional underground mining | |

| Eneabba Gas (WA) | Oct. 2008 | July 2015 | Preference for conventional oil and gas exploration | |

| Central Petroleum (NT) | June 2011 | Gas to liquids | April 2012 | Board change. Return to oil and gas business |

| Wildhorse Energy | Sept. 2009 | Oct. 2014 | No Aust. Interests |

6.8 Governmental decision making

In the development of the commercial operations planned by Linc Energy, Carbon Energy, and Cougar Energy in Queensland, where each company relied on rapid progress to efficiently use funds raised from the public, delayed government decisions, especially those made without consultation, had a significant impact on company development.

Within the environment of uncertainty existing late in the 2000s, the following examples of the timeliness of Queensland Government responses can be documented:

• The UCG Policy announced the formation of an expert panel in February 2009. The membership of the panel was announced in October 2009 (8-month delay).

• Carbon Energy released a limited amount of wastewater into a creek bed in August 2009. It was requested to submit a report on the incident to the government, which it did in October 2010. In July 2011, it was issued with criminal charges for breaching environmental law (9-month delay). The charges were settled with payment of a fine with confirmation of no environmental harm.

• Carbon Energy submitted the required decommissioning report on its Bloodwood Creek pilot project in October 2014. It received no decision until a complete ban on UCG technology in Queensland was announced without consultation with the UCG industry in April 2016 (18-month delay).

• Cougar Energy applied for its mineral development license at Kingaroy in December 2007. It was eventually granted in February 2009, 14 days after the announcement of the UCG policy (14-month delay).

• Cougar Energy submitted a number of environmental evaluation reports to the government following a temporary shutdown notice received without prior consultation in July 2010. The last of these reports was submitted in December 2010, and a permanent shutdown notice was issued, again without prior consultation, on 11 July 2011 (6-month delay).

• On 1 July 2011, Cougar Energy was charged with breaching environmental law relating to the failure of one of its injection wells in March 2010 (16-month delay). As with Carbon Energy, the matter was settled by payment of a fine with confirmation of no environmental harm.

In announcing the permanent ban on UCG in April 2016, the Queensland Government stated that “we have looked at the evidence from the pilot operation of UCG and we've considered the compatibility of the current technologies with Queensland's environment and our economic needs. The potential risks to Queensland's environment and our valuable agricultural industries far outweigh any potential economic benefits.”

In its response to this announcement, Carbon Energy, as the only remaining UCG proponent active in Australia, issued several statements, including one (Carbon Energy, 2016b) reiterating the ISP's positive conclusions about the technology and also the following:

The unexpected announcement was delivered without consultation despite recent meetings being held with company and the government's acknowledgement that Carbon Energy had worked openly and transparently with government.

While the detail of the environmental charges against Linc Energy appear to be serious and have some evidentiary backing, the charges against Carbon Energy and Cougar Energy were minor issues related to the normal course of business, confined to the immediate project operating zone, resolved speedily by the companies, and no different from similar operating issues occurring at mining or gas production facilities. The fact that they were treated with such severity, and with attached publicity despite acceptance that no environmental harm was caused, is confirmation of the significance of political factors operating at the time.

6.9 Conclusions and the future

Australia has made a significant contribution to the development of underground coal gasification technology over the last 40 years. The key features of this contribution can be summarized as follows:

• A focus since the 1970s on taking existing UCG technology through to commercialization.

• The introduction of private capital, through stock exchange listing, to provide substantial investment funding.

• The production of syngas from three UCG development sites since 1999 as the first stage in development of commercial projects. Only two other sites internationally (in South Africa and New Zealand, respectively) have reliably produced syngas over this period.

• The development of project plans from these three companies to produce a range of end products—liquid fuels, ammonia and methanol, and power generation.

• A total combined expenditure on the UCG effort in Australia estimated at A$500 million.

The ultimate collapse of this extensive UCG effort can be attributed largely to political decision-making in Queensland resulting from the conflict between the technologies of CSG and UCG developing over the same period of time and utilizing the same coal deposits. Efforts to find common ground between the proponents of each technology were not successful, and the size and established permit position of the CSG industry effectively led to the government decision to ban UCG technology in that state.

This decision has effectively made the progress of UCG technology in other states of Australia difficult, particularly given the mounting environmental campaigns against any technologies that may create groundwater impacts. The complexities in presenting and utilizing UCG technology mean that creating a technical understanding in response to these concerns is difficult, especially as critics are apt to fall back on the so-called precautionary principle as a justification for not supporting development of the technology.

In considering the lessons that come from the UCG program in Australia, the overriding issue involves the interaction between government and UCG proponent in relation to the monitoring and setting of acceptable limits for potential groundwater contaminants such as benzene and phenols. This process is no different from the processes used in many other operations such as waste disposal or chemical manufacture. These issues are discussed in detail elsewhere (Walker, 2014), and it is essential that they be confronted and agreed prior to any significant project investment.

The role of governments in the cycles of UCG development over many years has largely been the provision of funding for R&D programs, which have led to intense efforts in the FSU (from the 1930s to 1960s) and the United States (from the 1970s to 1980s). The past progress in Australia confirms that alternative funding from private sources can be attracted on the back of using established technologies applied to commercial project plans that meet local energy needs. However, it has also shown the power of government to selectively use environmental law and community perceptions of the technology to support alternative energy options where it chooses.

It is essential if future commercial development of UCG technology is to occur that it be undertaken where it can satisfy projected energy shortfalls, where long-standing technologies do not have the same resource control as existed in Queensland, and where full government support exists in the execution of practical environmental permitting that protects the community and allows controlled project development to occur.

Unfortunately, it appears that these conditions will not be met in Australia for the foreseeable future as a result of the technology perceptions created by the events that took place in Queensland. A change of approach may only happen if a commercial project is clearly demonstrated outside the country. Given the evidence available from companies previously active in Australia, this demonstration is most likely to occur in the Asian region.