Gasification kinetics

H. Bockhorn Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Engler-Bunte-Institute, Karlsruhe, Germany

Abstract

In this chapter the kinetics of underground coal gasification will be discussed. Underground gasification is characterized as a zonal process with time and space dependent state variables. This creates operating and boundary conditions for the different gasification processes, which cause changes in the reaction mechanisms and, hence, the kinetic rate laws. In addition due to the heterogeneity of the processes mass transport and energy transport limitations can occur. The kinetics of the different processes occurring during underground coal gasification—drying, devolatilization, gasification, combustion as well as reactions between the products of the different processes—are exemplified and discussed with regard to peculiarities compared with homogeneous reactions.

Keywords

Reaction rates; Heterogeneous reaction rates; Transport limitations; Reaction rate laws

7.1 Introduction

7.1.1 An attempt to a molecular view

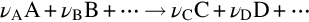

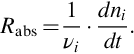

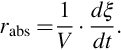

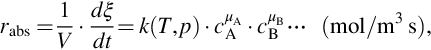

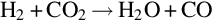

Considering a chemical reaction of the type

in a closed vessel, the chemical reaction rate Rabs is defined as the time change of the molar amounts dni/dt of the species i divided by its stoichiometric coefficients

The advantage of this definition is that we have a unique reaction rate for any species. Expressing the change of the molar amounts with the help of a conversion variable dni = νidξ, we can write

For chemical reactions in a homogeneous phase Rabs usually is expressed as a volume-specific quantity, therefore

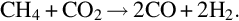

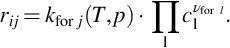

The volume-specific chemical reaction rate rabs depends on the molar concentrations ci of the involved species, temperature T, and pressure p. These dependencies can be expressed generally in a separable form like

where the temperature dependency is contained in the rate coefficient k(T, p) and the dependency on species concentrations is reflected by  . The rate coefficient can also be dependent on pressure and the chemical reaction rate is inherently dependent on pressure through the pressure dependency of species concentrations. The μi are the reaction orders with respect to the species i and

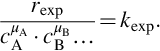

. The rate coefficient can also be dependent on pressure and the chemical reaction rate is inherently dependent on pressure through the pressure dependency of species concentrations. The μi are the reaction orders with respect to the species i and  is the overall reaction order of the chemical reaction. If the chemical reaction written as in Eq. (7.1) is an elementary reaction, that is, the reaction equation represents the mechanism of the reaction and the reaction proceeds on a molecular level as written, the reaction orders μi equal the stoichiometric coefficients νi. However, this is not the case for most reactions and particularly—as we will see later on—in the case of coal gasification. Experimental reaction rates rexp mostly are evaluated in the form

is the overall reaction order of the chemical reaction. If the chemical reaction written as in Eq. (7.1) is an elementary reaction, that is, the reaction equation represents the mechanism of the reaction and the reaction proceeds on a molecular level as written, the reaction orders μi equal the stoichiometric coefficients νi. However, this is not the case for most reactions and particularly—as we will see later on—in the case of coal gasification. Experimental reaction rates rexp mostly are evaluated in the form

For temperature ranges not too large the temperature dependency of kexp mostly is represented by an Arrhenius approximation

where EA app denotes the apparent activation energy.

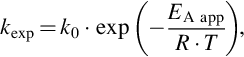

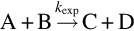

Experimental rate coefficients may be interpreted with the help of appropriate reaction rate theories. The simplest approach to the interpretation of kexp for a bimolecular reaction

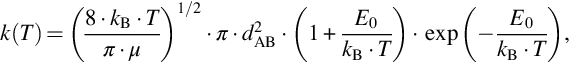

is collision theory, which gives for the hard sphere molecule model the intrinsic reaction rate coefficients k(T) as

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, dAB the intermolecular distance, μ the reduced mass, and Eo a threshold energy, which must be exceeded by the kinetic energy of the colliding molecules for successful reaction. Without going too much into detail we see that the approach to the temperature dependency as given in Eq. (7.7) is only an approximation useful for parameterizing experimental reaction rates.

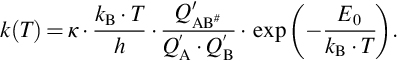

The more sophisticated approach of transition state theory of chemical reaction rates gives the rate of the bimolecular reaction Eq. (7.8) as translational flux of the involved molecules along the reaction trajectory and the intrinsic reaction rate coefficient is given by

In Eq. (7.10) h is Planck's constant, E0 is the energy difference between the rovibrational ground states of the transition state AB# and the reactants A and B, and  with Qi the partition function of educts A and B and the transition state AB#, respectively, the latter one without the vibrational degree of freedom along the reaction trajectory. κ represents a transmission coefficient describing the probability of forward decomposition of the transition state. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss in detail the recent developments of transition state theory (for details see e.g., Battin-Leclerc et al., 2013; Steinfeld et al., 1989; Wright, 2005); however, it should be noticed that again the simple Arrhenius temperature dependency of the rate coefficient is an approximation valid only for a limited range of experimental conditions. Prerequisites of the transition state approach are the potential energy surfaces of the involved molecules in dependency on the atomic distances and directions of mutual approach.

with Qi the partition function of educts A and B and the transition state AB#, respectively, the latter one without the vibrational degree of freedom along the reaction trajectory. κ represents a transmission coefficient describing the probability of forward decomposition of the transition state. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss in detail the recent developments of transition state theory (for details see e.g., Battin-Leclerc et al., 2013; Steinfeld et al., 1989; Wright, 2005); however, it should be noticed that again the simple Arrhenius temperature dependency of the rate coefficient is an approximation valid only for a limited range of experimental conditions. Prerequisites of the transition state approach are the potential energy surfaces of the involved molecules in dependency on the atomic distances and directions of mutual approach.

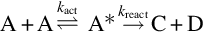

The explanation of the pressure dependency of the reaction rate coefficients for thermal monomolecular dissociation reactions

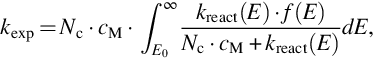

via the bimolecular activation mechanism of Lindemann

in principal reproduces the fall-off behavior of the rate coefficients with increasing pressure

Here cA is the concentration of A which acts also as a collision partner, kact the rate coefficient of the activation step, and  the high-pressure limit

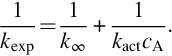

the high-pressure limit  of the rate coefficient. Extending the activation mechanism by introducing of energy-specific rate coefficients leads to

of the rate coefficient. Extending the activation mechanism by introducing of energy-specific rate coefficients leads to

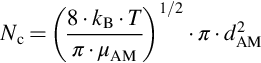

where Nc is the gas kinetic collision number for the hard sphere molecule model (see Eq. 7.9),

and cM the concentration of a collision partner. This extension introduces the energy-specific rate coefficient kreact(E) and the distribution function f(E) of the reactant molecule over the possible energy states. In the recent past this approach has been expanded with the help of statistical reaction rate theory (see e.g., Olzmann, 2013). The approach employs master equations with energy-specific rate coefficients kreact(E) for every possible energy state from Rice-Ramsperger-Kassel-Marcus (RRKM) statistical theory and the simplified statistical adiabatic channel model and can be used for reactions over potential energy barriers and potential energy wells. The macroscopic rate coefficient k(T, p) of a unimolecular reaction under steady-state conditions is then obtained by averaging its energy-specific rate coefficients over the normalized energy distribution of the reactant. The method is also based on the knowledge of the detailed respective potential energy surfaces.

This is the—often hard to access—idyllic world of reaction kinetics for homogeneous systems and the question arises whether—and if not why—kinetics of underground gasification of coal fits into this world.

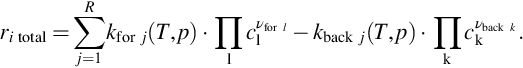

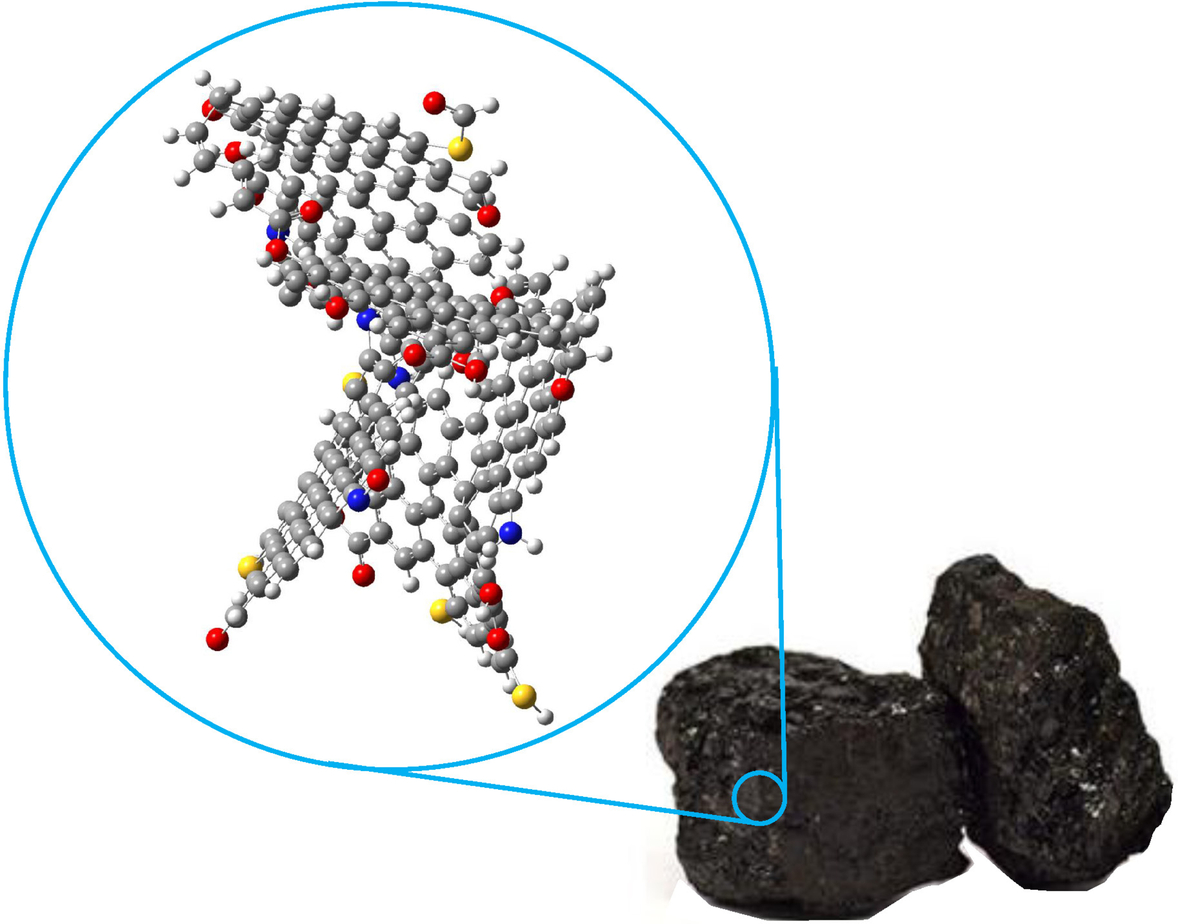

Coal originates over million of years from large amounts of biomasses through biochemical and geochemical processes. The extent of coalification determines the degree of conversion of the original biomass to carbon. The degree of conversion is attributed to a number of properties, summarized as the rank of the coal, and Table 7.1 exhibits a wide variation of the elemental composition connected with the content of volatile matter (VM), content of water, and calorific value (CV) consolidated as the rank of coal.

Table 7.1

Variation of coal properties with rank (Laurendeau, 1978; van Krevelen, 1961)

| Rank | % C | % H | % O | % VM | CV (MJ/kg) | % H2O |

| Lignite | 65–72 | 4.5 | 30 | 40–50 | <19.4 | >15 |

| Subbituminous (A, B, C) | 72–76 | 5.0 | 18 | 35–50 | 19.4–25.6 | 10–15 |

| Bituminous (C) | 76–78 | 5.5 | 13 | 35–45 | 25.6–30.2 | 5–10 |

| Bituminous (B) | 78–80 | 5.5 | 10 | 31–45 | 30.2–32.6 | 3–5 |

| Bituminous (A) | 80–87 | 5.5 | 4–10 | 31–40 | 33.8 | 1–2 |

| Bituminous (MV) | 89 | 4.5 | 3–4 | 22–31 | 34.9 | <1 |

| Bituminous (LV) | 90 | 3.5 | 3 | 14–22 | 36.8 | <1 |

| Anthracite | 93 | 2.5 | 2 | <14 | 35.4 | <1 |

Note: Composition is given in percentage (mass) of dry mineral matter free coal.

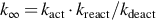

The complexity of the chemical structure of coal, documented by the variation in elemental composition, is reflected by model molecules for coal. One model molecule for bituminous coal is depicted in Fig. 7.1. The coal molecule is characterized by a variety of organic functional groups containing the chemical elements C, H, O, N, and S. The fundamental carbon structures are the polynuclear aromatic, the hydroaromatic, and the aliphatic ones accounting for the largest part of carbon and hydrogen. Furthermore, oxygen-containing functional groups like carboxyl, carbonyl, and ether groups or OH groups are present as well as heterocyclic oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur-containing groups. Thus coal is a complex structured “molecule” and we cannot expect that gasification of coal can be resolved into simple sequences of reactions between well-defined molecules as written in Eq. (7.1) or (7.11). Moreover, the different types of chemical bonds exhibit different bond energies, so that during gasification of coal the structure and reactivity of coal will change because functional groups with the weakest bonds will be eliminated first. As a consequence the mechanism and type of reactions will change during the progress of gasification.

The brief view upon that model molecule for coal, therefore, provides some obvious answers to the previous question:

• For the kinetics of coal gasification we will not expect a unique chemical reaction mechanism and unique rate expressions derived from the earlier briefly sketched (and advanced for application) theories.

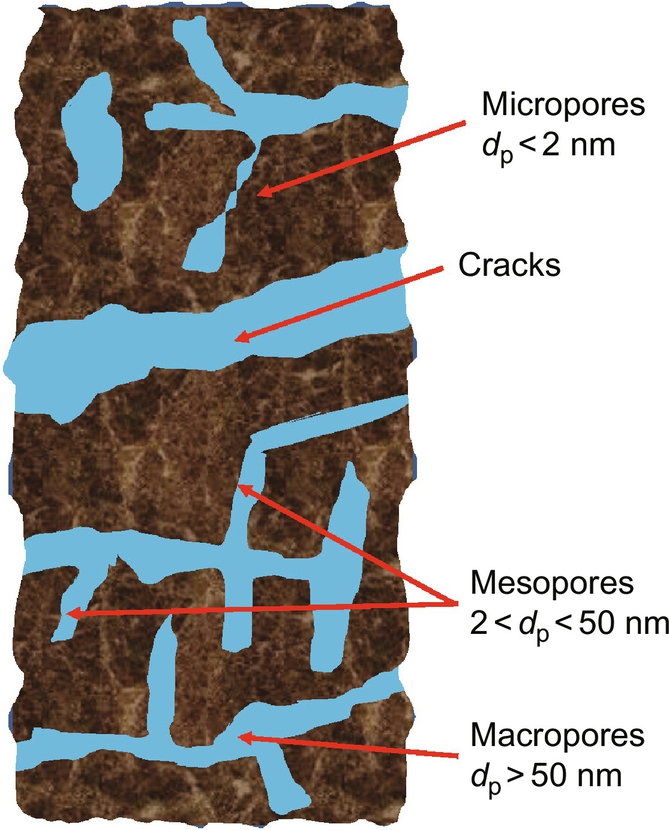

• Furthermore, the “coal molecules” are assembled irregularly to a solid that exhibits a porous structure with pore sizes dp ranging from micropores/nanopores with dp < 2 nm, mesopores with 2 nm < dp < 50 nm to macropores with dp < 50 nm. The largest part of solid coal surface where the gasification reactions occur is presented by the internal surface of this porous structure so that gasification reactions are coupled with transport processes through this porous structure to the internal surface.

• Depending on the ratio between transport rates and chemical reaction rates, the apparent reaction kinetics are superposed intrinsic reaction kinetics and transport rates.

7.1.2 Gasification on the technical scale

Underground coal gasification as performed in coal seams is a zonal process. This is the consequence of the gas-solid heterogeneous character of coal gasification and the fact that in underground coal gasification no feeding of coal through a gasification reactor is possible. In contrary, the “gasification reactor” migrates through the coal seam and only the gaseous reaction components are fed into and withdrawn from the moving reactor. Therefore, only a limited number of operating conditions are free to handle and the overall process is to a large extent autonomous, meaning that, for example, the necessary heat of reaction for the gasification of coal has to be provided by utilization of a part of the coal or that the amount of water expended for gasification is defined by the water content of the coal. The “coal molecule” then undergoes necessarily completely different types of reactions to keep the overall gasification process running. From this view we receive a further answer to the initial question:

• Apparent kinetics of underground gasification is intrinsic kinetics coupled with energy and mass balances of the zonal process.

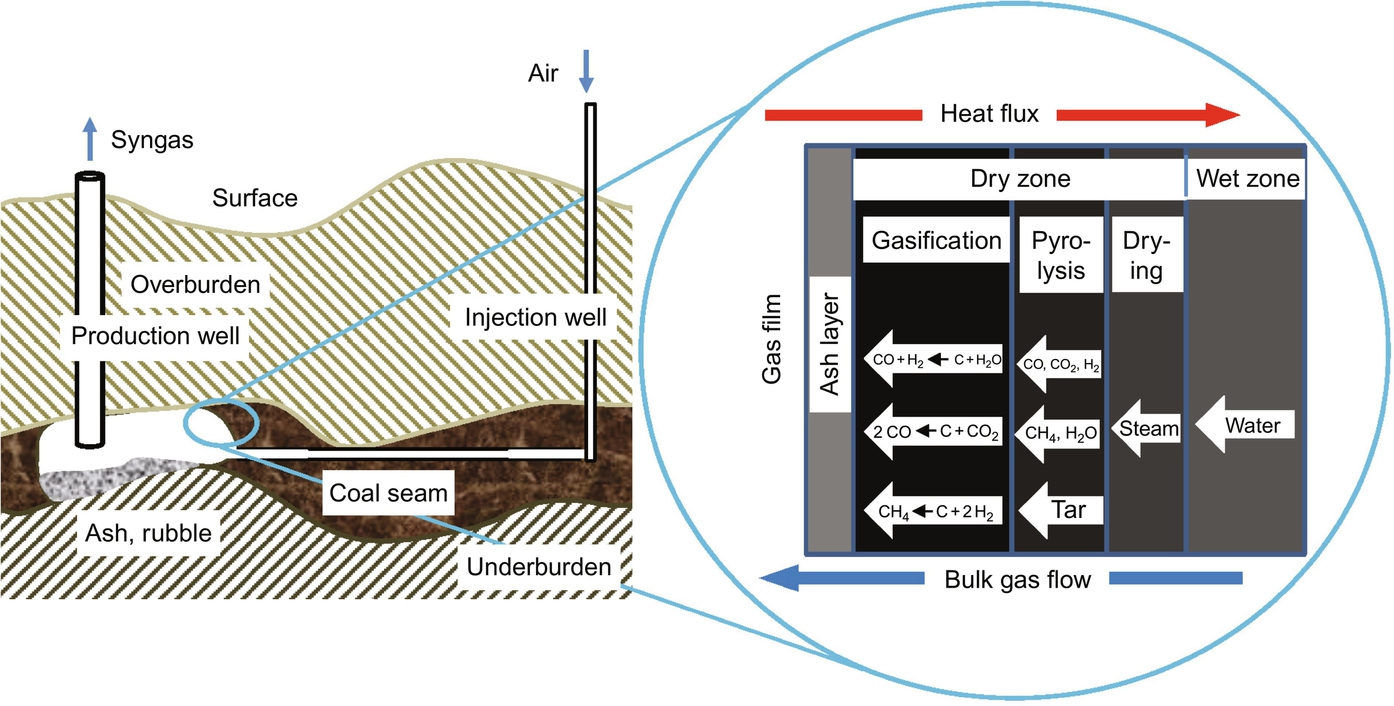

Fig. 7.2 presents a scheme of underground coal gasification employing the controlled, retractable injection point (CRIP) process. This technique provides a more controllable operating of underground gasification by varying the distance between the production well and the injection well according to the progress of coal consumption. Looking at the enlarged section of the boundary between the gas phase and the solid, five layers in the simplified exposure can be observed with different processes occurring within those layers. At the cold end in the wet zone the original coal of the seam is present which contains water according to the hydrogeological conditions and history of the seam. Depending on these conditions a more or less influx of water into the adjacent zone can occur. The problem for the overall process of underground coal gasification is that this boundary condition can vary with time and often is ill defined or unknown.

Subsequent in the direction to the solid-gas phase boundary the drying zone follows where solely water is vaporized and the resulting steam is possibly overheated under the prevailing conditions. The necessary vaporization energy is provided by heat conduction from the hot pyrolysis zone and the “kinetics” of vaporization are determined by the energy and mass balances for heat transfer and vaporization. Again the problem arises that the boundary conditions for these processes are not well-defined and time-dependent and, furthermore, for example, heat conductivities for the coal are uncertain due to the content of included rock and material properties may not be homogeneous and isotropic.

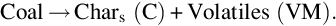

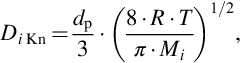

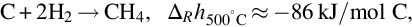

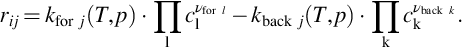

As can be seen from Table 7.1 bituminous coal contains up to 45% by mass volatiles which are released at higher temperatures in the pyrolysis zone according to the overall endothermic global reaction

Evolution of volatiles from coal is a result of complex chemical reactions, which eliminate the less stable functional groups contained in the coal molecule. According to the single building blocks of the coal molecule the gaseous products of this kind of reactions mainly are higher hydrocarbons, denoted as tar, smaller hydrocarbons, CH4, H2, CO, CO2, and H2O. The solid product of devolatilization and pyrolysis is char—denoted as C in Eq. (7.16)—with a high C/O- and C/H-ratio, compare Table 7.1. Together with the steam from the drying zone the pyrolysis products flow into the char gasification zone where they undergo further heterogeneous and homogeneous secondary reactions.

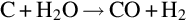

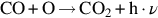

Finally, gasification of char occurs in the char gasification zone primarily by the two highly endothermic gasification reactions

and

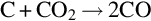

and to a less extent by the slightly exothermic reaction

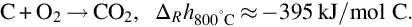

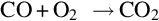

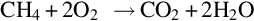

The overall gasification process is endothermic and the necessary reaction energy as well as the necessary energy for vaporization and devolatilization has to be provided and balanced by combustion of a part of the char

Combustion according to Eq. (7.20) is performed with air being fed through the injection well and proceeds near the phase boundary char-gas. The energy released by combustion is transported by heat conduction from that region converse to the bulk gas flow into the gasification zone, the pyrolysis zone and the drying zone to keep the process running.

The content of anorganics in the char from included or embedded minerals remains as ash layer covering the char. The products of gasification and the reactants must be transported through that ash layer and the rate of mass transfer may under circumstances determine the kinetics of the process.

In the gas phase secondary homogeneous reactions between the products of gasification and devolatilization and oxygen may occur.

In summary from the simplified schematic in Fig. 7.2 for underground coal gasification different classes of chemical reactions can be identified, namely

• drying of wet coal (vaporization of water);

• devolatilization and pyrolysis of coal;

• heterogeneous gasification of char;

• heterogeneous oxidation of char; and

• homogeneous (and heterogeneous) secondary reactions of gasification and pyrolysis products.

The kinetic aspects of which in connection with transport processes and mass and energy balances will be discussed in the following sections.

7.2 Kinetic aspects of the different classes of reactions during gasification

As discussed in Section 7.1.2 underground coal gasification consists of chemical reactions interacting with mass and energy transport. The chemical reactions are to the largest part heterogeneous with consumption of the solid phase. In contrast to Eq. (7.5), therefore, different methodology for the formulation of apparent reaction rates has to be used encompassing intrinsic reaction kinetics superposed with mass and energy transfer rates. The different types of transport processes and chemical reactions are distributed over different layers of the coal seam with different physical and chemical properties, leading to unknown or not well-defined and time-dependent operating and boundary conditions, complicating additionally the considerations.

7.2.1 “Kinetics” of drying

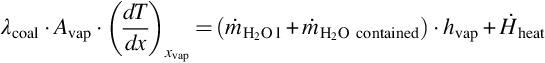

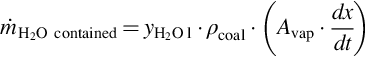

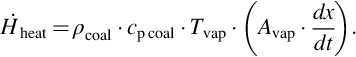

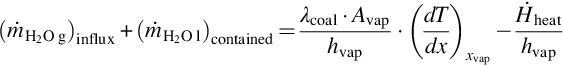

In the drying zone water is heated from the conditions in the wet zone to the boiling point under the prevailing conditions and the steam is overheated to the conditions of the adjacent boundary of the pyrolysis zone, compare Fig. 7.2. The necessary energy for drying and overheating is provided by heat conduction from the pyrolysis zone and occurs in counter flow to the transport of water/steam. For the surface of vaporization at temperature Tvap in the drying zone an energy balance can be drafted, which equalizes the most prominent heat fluxes (i.e., the heat flux by conduction, the heat of vaporization of the inflowing and contained water, and the heating of the solid)1

with

and

Eqs. (7.22), (7.23) reflect that the surface of vaporization migrates toward the wet zone inducing a time change of the vaporization volume (Avap ⋅ dx/dt). In Eqs. (7.21)–(7.23)  is the mass flux of water into the drying zone, hvap is the mass-specific heat of vaporization under the prevailing conditions, yH2O l is the mass fraction of water in the coal, and Avap is the area of the surface of vaporization. Material properties of the coal, namely heat conductivity λcoal, specific heat capacity cp coal, and density ρcoal, are averaged values. This formulation assumes that the contained water is in thermal equilibrium with the solid. Eq. (7.21) can be transformed to give the migration rate of the surface of vaporization dx/dt

is the mass flux of water into the drying zone, hvap is the mass-specific heat of vaporization under the prevailing conditions, yH2O l is the mass fraction of water in the coal, and Avap is the area of the surface of vaporization. Material properties of the coal, namely heat conductivity λcoal, specific heat capacity cp coal, and density ρcoal, are averaged values. This formulation assumes that the contained water is in thermal equilibrium with the solid. Eq. (7.21) can be transformed to give the migration rate of the surface of vaporization dx/dt

Eq. (7.24) reveals that the surface of vaporization migrates toward the wet zone if there is no influx of water from the wet zone and the migration rate increases with increasing heat conductivity λcoal and temperature gradient  and decreasing water content yH2O l of the coal. Increasing influx of water reduces the migration rate and effects a stationary situation for the two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. (7.24) being balanced. If the last term on the right-hand side overtops the first term, the migration rate changes its direction and the surface of vaporization moves toward the pyrolysis zone.

and decreasing water content yH2O l of the coal. Increasing influx of water reduces the migration rate and effects a stationary situation for the two terms on the right-hand side of Eq. (7.24) being balanced. If the last term on the right-hand side overtops the first term, the migration rate changes its direction and the surface of vaporization moves toward the pyrolysis zone.

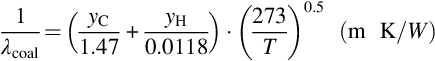

The heat conductivity λcoal of coal enters the balance equations discussed earlier. The variation of the thermal conductivity of a solid with temperature depends on the type of material. The conductivities of most metals decrease with temperature, whereas the conductivities of nonmetals increase and the variations in thermal conductivity usually parallel those of electrical conductivity. Experiments on heat conductivities of coals show a rise with increasing temperature, which has been attributed to radiant heat transfer across pores and cracks, changes in the conductivity of the coal due to pyrolysis and changes in the intrinsic conductivity with temperature. Coal can be regarded as nonmetal and the rise in thermal conductivity observed at temperatures below 600°C is likely to be due to the latter effect. To account also for the elemental composition relations for the thermal conductivity of coals such as

have been proposed (Merrick, 1987). In Eq. (7.25) T is the absolute temperature and yC and yH are the mass fractions of carbon and hydrogen, respectively, assuming that the contributions for each element are additive. To be applicable to coals in coal seams relations of the earlier kind have to be extended to reflect inclusions of minerals and the porous structure of the coals. The effective heat conductivity then is lower compared with the heat conductivities according to Eq. (7.25), which lie in the order of magnitude of 3 W/(m K) at 600°C.

Rearranging the energy balance Eq. (7.21) into

demonstrates that the flux of the generated steam is linearly correlated with the temperature gradient (dT/dx)xvap at the vaporization surface the formation of steam, hence, being of “first order” in temperature. Variations in the inflowing or contained water lead to variations in the temperature gradient and migration rates.

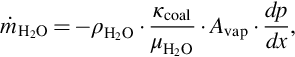

Vaporization also is affected by mass transport of the inflowing water and/or generated steam. As mentioned in Section 7.1.1 coal offers a porous structure with different sized pores, see Fig. 7.3. Pore sizes range from smaller than 2 nm diameter for micropores to larger than 50 nm for macropores. Depending on the geohistoric situation also cracks with macroscopic dimensions and closed pores or cavities are present. Water contained in this porous structure or entering from the wet zone and steam generated during drying have to be transported in counterflow to the heat flux versus the pyrolysis zone. Depending on the pore sizes this transport can occur by viscous flow or diffusion.

For viscous flow the volumetric flow rate is given by Darcy's law and proportional to the pressure gradient with

where μH2O is the viscosity of water and κcoal the permeability of the coal. Similar to the heat conductivity of the coal the latter properties are dependent on the prevailing conditions and ill defined and may change during the drying process.

Diffusional transport of species through the porous structure from a macroscopic point of view is described by an empirically derived effective diffusivity Deff and the mass fluxes are expressed with the help of Fick's diffusion law

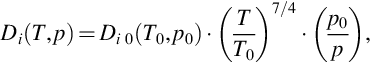

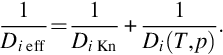

The effective diffusivity Di eff represents the reciprocal of a diffusional resistance throughout the coal layer. From a microscopic approach, diffusion through a single pore rather than the entire porous particle is considered. The overall particle is depicted by an appropriate combination of single pores. Diffusion through an individual pore is described using capillary diffusion theory and according to that isobaric flow through a pore may involve molecular diffusion or Knudsen diffusion. Molecular diffusion becomes the predominant mode of transport whenever the pore size is large compared to the mean free path of the diffusing species dp/λi > 10. The molecular diffusion coefficient is a function of temperature and pressure and can be expressed according to the kinetic theory of gases by

where the index 0 refers to a reference state.

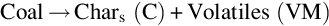

Knudsen diffusion is molecular transport via collisions with the walls of the pores and occurs primarily when the pore size is small with respect to the mean free path of the molecules dp/λi < 0.1. For smooth pores, the Knudsen diffusion coefficient can be expressed as

where Mi is the molar mass of the species i. From Eq. (7.30) it can be seen that the Knudsen diffusion coefficient Di Kn in contrast to the molecular diffusion coefficient is independent of pressure and linearly proportional to pore diameter. Diffusion coefficients can be interpreted as reciprocal normalized diffusion resistances. Therefore, the combined effects of both Knudsen and molecular diffusion can be modeled as the addition of the respective resistances

Fig. 7.3 exhibits that the material properties of coal due to the inclusion of pores and minerals are nonisotropic and heat conduction, for example, in the solid coal occurs with a different conductivity than in the water filled pores or in the rock leading necessarily to a three-dimensional heat conduction/heat transfer problem.

Despite the simplifications used here, the earlier discussion clearly documents that heat flux, extension, and location of the drying zone as well as migration rate adjust interdependently to variations of the flux and content of water. The flux of steam from the drying zone and the temperature gradient at the surface of vaporization in the drying zone are linearly related. The time change of the molar amount of water in the drying zone volume which represents a reaction rate for the “drying reaction” according to Eq. (7.2) or (7.5) then is of first order in temperature.

7.2.2 Devolatilization kinetics

As noted in Section 7.1.2 devolatilization of coal according to the overall endothermic formal reaction

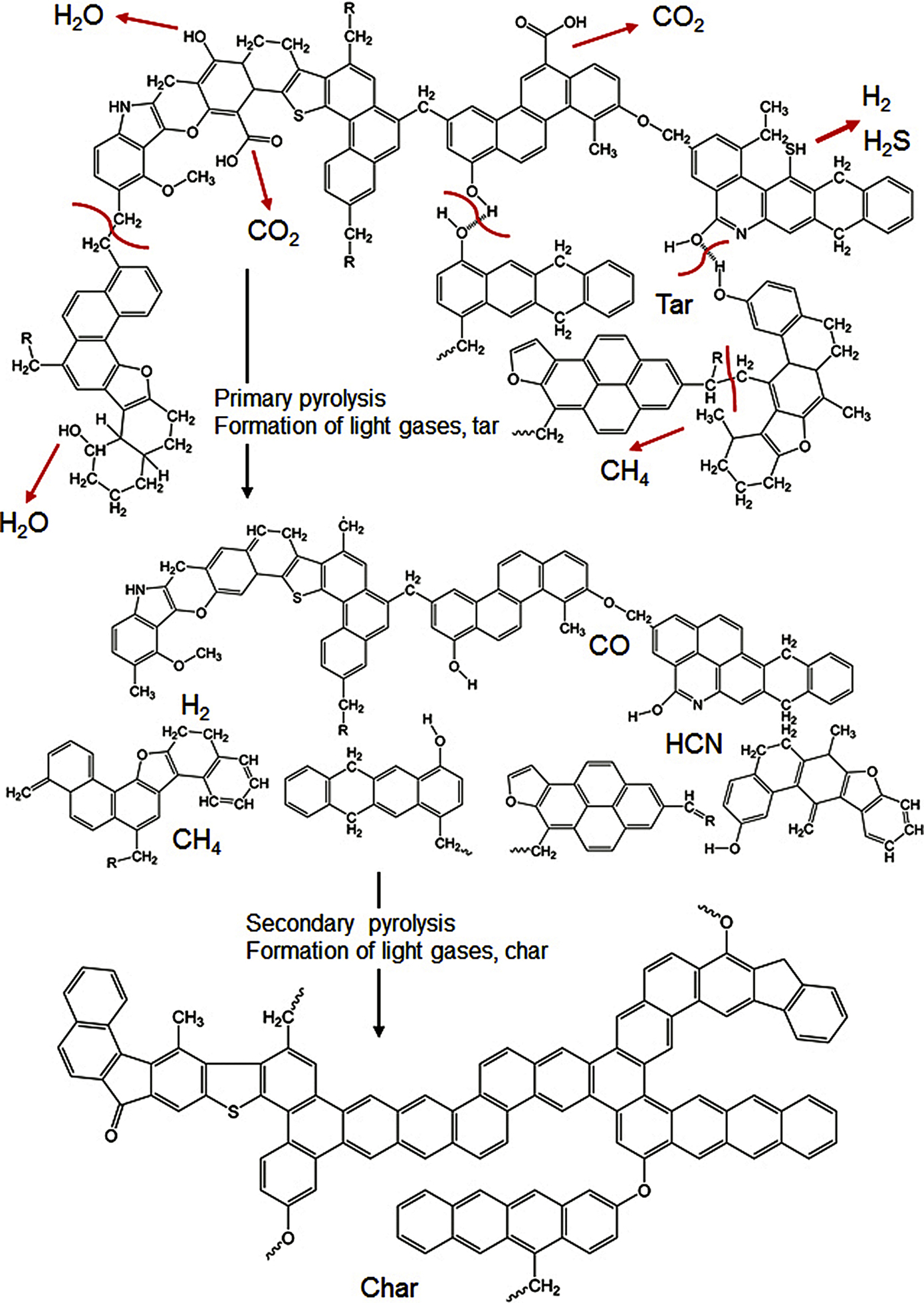

occurs via a complex reaction mechanism with numerous single chemical reactions in the solid phase eliminating the less stable functional groups contained in the coal molecule outlined in Fig. 7.1. The reaction is of heterogeneous type with depletion of the solid phase and formation of gaseous and liquid phases. A general qualitative scheme (Solomon et al., 1988, 1992) for the chemical reactions occurring during devolatilization of coal derived from the coal molecule is depicted in Fig. 7.4. This coal molecule represents the chemical compositions and functional groups for a bituminous coal (Solomon et al., 1988). It consists of aromatic and hydroaromatic clusters including heterocycles linked by aliphatic bridges and is the point of origin of devolatilization reactions. Starting from the coal molecule in the raw coal the figure exhibits the formation of tar and light hydrocarbons during primary pyrolysis, and the formation of char through condensation and cross-linking during secondary pyrolysis.

During primary pyrolysis the weakest bridges indicated by red lines in the structure break producing mean sized molecular fragments. The fragments abstract hydrogen from the hydroaromatics or aliphatics, increasing the aromatic character of the residue. The formed fragments are released as tar if they are small enough to vaporize. At the prevailing temperatures in the pyrolysis zone growth reactions appear to be slower than bond-breaking reactions. Therefore, the smaller fragments are transported out of the pyrolysis zone under typical pyrolysis conditions and do not undergo pyrolytic growth reactions before escaping from the pyrolysis zone. Growth reactions are connected to formation of CH4 and lead to higher molecular weight components which are too large to vaporize and result in the formation of a type of tar which contributes to char formation.

The other processes during primary pyrolysis are the decomposition of functional groups to release gases, mainly CO2, light aliphatic hydrocarbons, and some CH4 and H2O. The release of CH4, CO2, and H2O is followed by growth reactions via cross-linking. Cross-linking reactions are induced via CH4 by a substitution reaction in which the attachment of a larger molecule releases the methyl group. CO2 induces cross-linking by condensation after a radical is formed on the ring when a carboxyl is removed. Cross-linking via H2O occurs by condensation of two OH groups or an OH group and a COOH group. The competition between growth reactions and bond-breaking reactions determines the tar content of the char. The drift off of primary pyrolysis is connected with the depletion of disposable hydrogen from hydroaromatic or aliphatic portion of the coal.

During secondary pyrolysis there is additional formation of light gaseous molecules, CH4 from methyl groups, HCN from heterocyclic nitrogen compounds, CO from ether links, and H2 from ring condensation.

7.2.2.1 Kinetic description

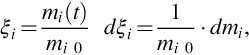

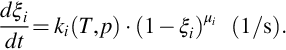

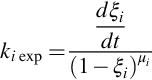

The kinetic description of the devolatilization of coal obviously possesses two principal difficulties: first, devolatilization of coal is a very complex process between heterogeneous phases consisting of numerous bond-breaking elementary steps occurring for a wide variety of chemical bonds between divers reaction centers located at vastly different molecular (polymeric) structures. Rate equations for the devolatilization of solids can be derived from molecular mechanisms, for example, the thermal decomposition of single monomer polymers (Bockhorn et al., 1999, 2000); however, there is no hope to find an analogous way for the devolatilization of coal. Therefore, the formation reactions of the different pyrolysis products are mostly lumped together in single global reactions. Due to the predominating bond-breaking reactions the supposition of first-order reaction kinetics often seems to be justified. Second, the reaction products are partially gaseous, liquid, and solid, and for an appropriate kinetic description an adequate conversion variable has to be defined. For the products evolving from the solid coal structure during devolatilization the conversion variable can be given as

where mi(t) is the amount of species i formed until time t and mi 0 is the ultimate amount which is a priori unknown and a function of the rank of coal (see Table 7.1). The conversion variable in terms of masses seems to be appropriate in this case because molecular structures and molar masses of the volatiles (e.g., tars) are unknown. As evolution of volatiles diminishes with reaction progress, kinetic rate equations unlike Eq. (7.5) are written in the form

In Eq. (7.34) ki(T, p) is the respective rate coefficient and μi the reaction order with respect to species i. Evaluating experimental conversion rates to obtain

yields then an apparent rate coefficient ki exp and its temperature dependency may be expressed with the help of Eq. (7.7) and an apparent activation energy. If a first-order reaction μi ≈ 1 is utilized, this formulation gives the rate as proportional to the instantaneous source of species i. Kinetic rate equations for the devolatilization of coal, therefore, are mostly written in the form of Eq. (7.34) and pool all reactions for the formation of single species or groups of species.

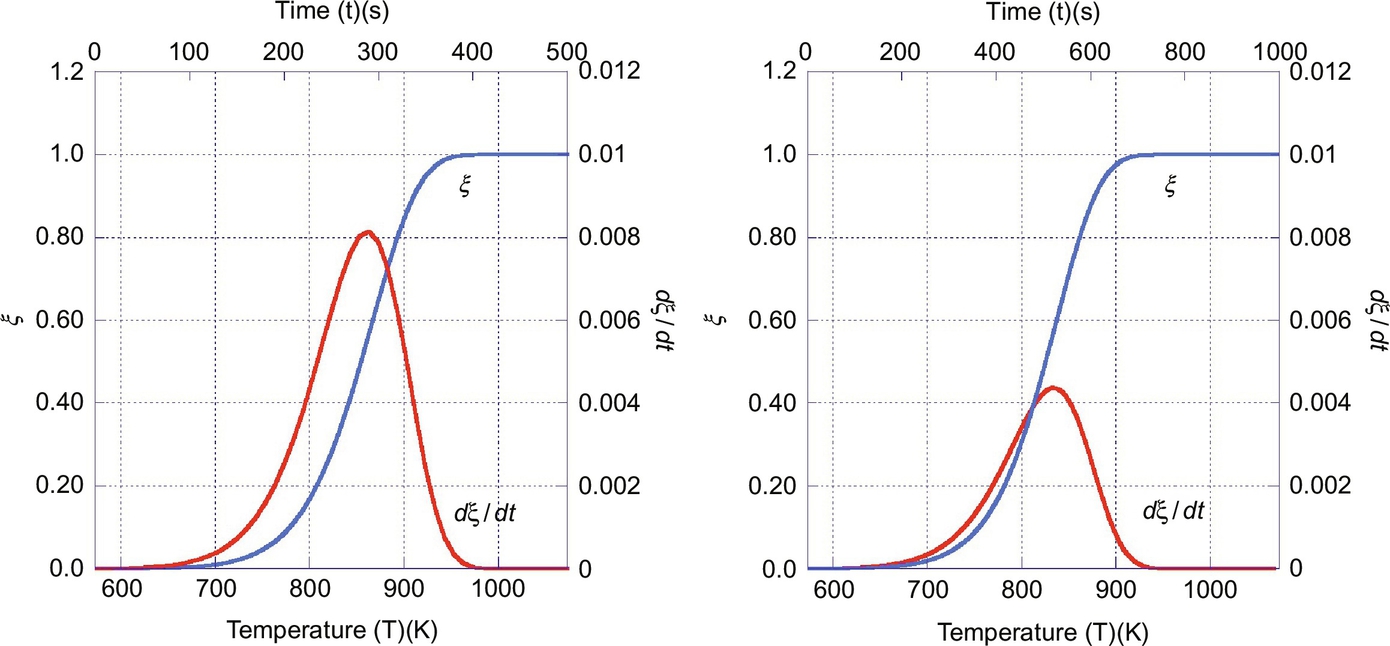

For a constant heating rate dT/dt = β which may prevail in underground gasification at a fixed location in the pyrolysis zone, temperature linearly increases with time T = T0 + β ⋅ t and Eq. (7.34) can be rewritten

Typical reaction rates dξ/dt and reaction progress ξ from the numerical integration of Eq. (7.36) for a reaction order μi = 1 in dependence on time t and temperature T are given in Fig. 7.5. The diagram exhibits the trace of the reaction rate from low values at low temperatures passing through a maximum and then approaching zero when the source of species i is depleted and the devolatilization is complete. Accordingly, the reaction progress ξ asymptotically approaches 1. Increasing the heating rate dT/dt shifts the maximum of the reaction rate to smaller times, however, due to the nonlinear dependence of the reaction rates on temperature to higher temperatures. The increasing branch of the reaction rate trace is due to the exponential dependency of reaction rate on temperature whereas the decreasing branch reflects the limitation of the source of the species. As the pyrolysis zone migrates through the coal seam reaction progress and reaction rates as given in Fig. 7.5 apply for a fixed location in the pyrolysis zone. However, migration of the pyrolysis zone produces a continuous formation of devolatilization products.

7.2.2.2 SRFOM approach

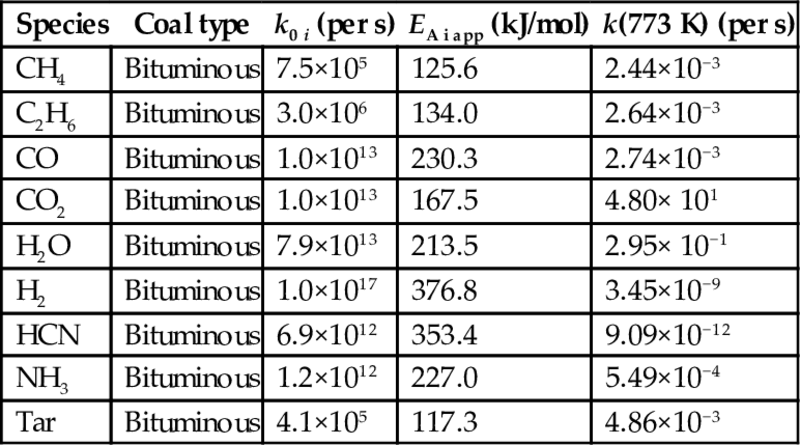

Rate coefficients kexp for the formation of pyrolysis products according to Eq. (7.34) are given in Table 7.2 (Serio et al., 1987; Solomon et al., 1992). The reaction model underlying these rate coefficients is a “single reaction first-order model” (SRFOM) and the parameters of the model are evaluated by fitting the model to experimental data. It should be noted that the results from this procedure may be affected by the kinetic compensation effect (Zsakó, 1976). The kinetic compensation effect is an apparent effect, which is due to the form of the Arrhenius equation. This effect consists of a correlation between the kinetic parameters of the decomposition reactions, so that the increase of the apparent activation energy is accompanied by an equivalent increase of the pre-exponential factor. Table 7.2 contains also the rate coefficients for the formation of different pyrolysis products at a temperature of 500°C. According to this data the by far fastest reactions are the formation reactions of CO2 and H2O and the rates of the formation reactions of CH4, C2H6, CO, and tar are by some orders of magnitude slower.

Table 7.2

Rate parameters kexp according to Eq. (7.7) for the formation of pyrolysis products according to Eq. (7.34) and the SRFOM approach (Serio et al., 1987; Solomon et al., 1992)

| Species | Coal type | k0 i (per s) | EA i app (kJ/mol) | k(773 K) (per s) |

| CH4 | Bituminous | 7.5×105 | 125.6 | 2.44×10−3 |

| C2H6 | Bituminous | 3.0×106 | 134.0 | 2.64×10−3 |

| CO | Bituminous | 1.0×1013 | 230.3 | 2.74×10−3 |

| CO2 | Bituminous | 1.0×1013 | 167.5 | 4.80× 101 |

| H2O | Bituminous | 7.9×1013 | 213.5 | 2.95× 10−1 |

| H2 | Bituminous | 1.0×1017 | 376.8 | 3.45×10−9 |

| HCN | Bituminous | 6.9×1012 | 353.4 | 9.09×10−12 |

| NH3 | Bituminous | 1.2×1012 | 227.0 | 5.49×10−4 |

| Tar | Bituminous | 4.1×105 | 117.3 | 4.86×10−3 |

7.2.2.3 DAEM or DRM approach

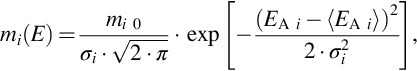

To consider the multiplicity of reactions for the formation of a single species from the variety of functional groups in the coal molecule the approach according to Eq. (7.34) is extended by introducing a distribution of activation energies EA and possibly frequency factors ko (distributed activation energy model [DAEM] or distributed rate model [DRM]). This model assumes that the ultimate amount mi 0 giving to the same pyrolysis product is somewhat inhomogeneous due to the different functional groups in the coal molecule. Instead of a single activation energy EA, the ultimate amount contains components having a distribution of activation energies about a mean 〈EA〉. As distribution function often the Gaussian distribution function is used

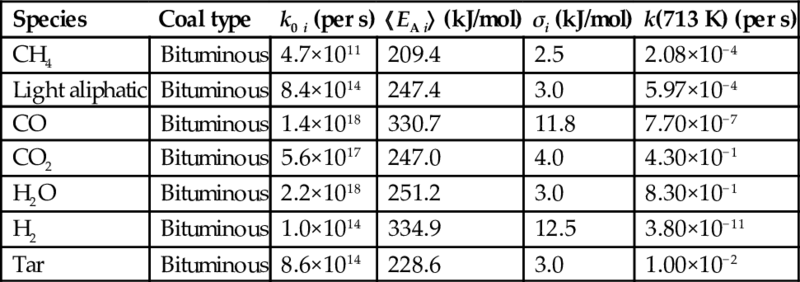

where mi(E) is the part of the ultimate amount with activation energy EA i, 〈EA i〉 is the mean activation energy, and σi is the width of the distribution. The integral of mi(E) over EA i is the ultimate amount of the species i. Some models also use both distributed activation energies and frequency factors. Rate coefficients for the distributed activation energy model are given in Table 7.3. The ratio of the rate coefficients for the formation of the single components at a constant temperature for SRFOM and DAEM is comparable. This approach often results in better fits of experimental data, however, does not resolve the principal problems connected with this method.

Table 7.3

Rate parameters kexp for the formation of pyrolysis products according to the distributed activation energy model Eq. (7.37) (Serio et al., 1984, 1987; Solomon et al., 1992)

| Species | Coal type | k0 i (per s) | 〈EA i〉 (kJ/mol) | σi (kJ/mol) | k(713 K) (per s) |

| CH4 | Bituminous | 4.7×1011 | 209.4 | 2.5 | 2.08×10−4 |

| Light aliphatic | Bituminous | 8.4×1014 | 247.4 | 3.0 | 5.97×10−4 |

| CO | Bituminous | 1.4×1018 | 330.7 | 11.8 | 7.70×10−7 |

| CO2 | Bituminous | 5.6×1017 | 247.0 | 4.0 | 4.30×10−1 |

| H2O | Bituminous | 2.2×1018 | 251.2 | 3.0 | 8.30×10−1 |

| H2 | Bituminous | 1.0×1014 | 334.9 | 12.5 | 3.80×10−11 |

| Tar | Bituminous | 8.6×1014 | 228.6 | 3.0 | 1.00×10−2 |

7.2.2.4 Reaction networks

The literature about coal devolatilization offers numerous approaches to resolve the complex chemical reaction mechanism into a more or less complex network of single chemical reactions. A first step into that direction is the description of devolatilization by two competing reactions

and

where the first reaction with a lower apparent activation energy predominates at low temperatures and the second one with high apparent activation energy at higher temperatures. With

a better fit for the experimental data for lignite and bituminous coal is obtained than with a single reaction approach (Kobayashi et al., 1977). This approach is extended to higher level of complexity by generalized devolatilization models such as tar formation models, species evolution/functional group models, and chemical network models that consider the evolution of single gas species. These models are based on the descriptions of the coal structure and on the processes that the coal experiences during devolatilization. One example of the tar formation models is the chemical percolation devolatilization (CPD) model (Jupudi et al., 2009). An example of the chemical network model is the functional group-devolatilization vaporization cross-linking (FG-DVC) model (Solomon et al., 1988). Predictions utilizing these models seem to be applicable over a wide range of coal types and process conditions as these models are based on fundamental processes occurring during devolatilization.

The FG-DVC model includes individual rate equations for various light gas species that evolve during devolatilization. The basis of this approach is that coal is viewed as an ensemble of functional groups that are organized into tightly bound aromatic ring clusters and are connected by bridges, see Fig. 7.4. Tar and light gas species are released by the thermal decomposition of these individual functional groups and the kinetics are expected to depend on the functional group or the nature of bond breaking (Solomon et al., 1988). One drawback of this approach is that the necessary structural data are not a priori available.

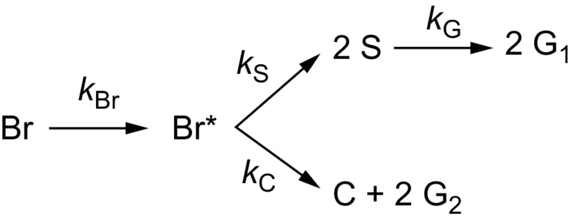

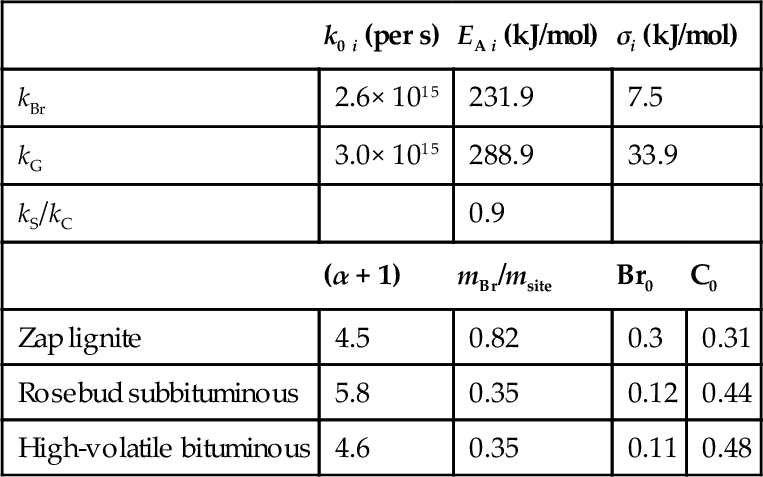

The CPD model considers the physical features of FG-DVC models and relates them to coal structural properties as inputs without any adjustable constants (Grant et al., 1989; Jupudi et al., 2009). The model employs percolation statistics to describe the generation of light gas/tar precursors of finite size based on the number of cleaved labile bonds in the infinite coal lattice. Coal-dependent chemical structure coefficients are taken directly from experiments, for example, by 13C NMR measurements, or by using correlations developed from experiments with several coals. In addition, coal-independent kinetic parameters are employed for the formation of the different components of the reaction network. Fig. 7.6 shows the simple reaction scheme in the original CPD model (Grant et al., 1989). The reaction starts with the cleaving of a chemical bond in a labile bridge (Br) to form a highly reactive bridge intermediate (Br⁎). The reactive bridge intermediate may either be released as a light gas (G2) with the concurrent relinking of the two associated sites within the reaction cage to give a stable or charred bridge (C). Or the bridge material may be stabilized to produce side chains (S) that may convert into light gas (G1) fragments through a subsequent slower reaction. Parameters of the CPD model are listed in Table 7.4 (Grant et al., 1989).

Table 7.4

Coal type independent rate parameters (upper part) and coal type dependent parameters (lower part) for the CPD model (Grant et al., 1989)

| k0 i (per s) | EA i (kJ/mol) | σi (kJ/mol) | ||

| kBr | 2.6× 1015 | 231.9 | 7.5 | |

| kG | 3.0× 1015 | 288.9 | 33.9 | |

| kS/kC | 0.9 | |||

| (α + 1) | mBr/msite | Br0 | C0 | |

| Zap lignite | 4.5 | 0.82 | 0.3 | 0.31 |

| Rosebud subbituminous | 5.8 | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.44 |

| High-volatile bituminous | 4.6 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.48 |

The parameters given in Table 7.4 can be used to simulate the evolution of the gaseous components G1 and G2 and formation of char C. The apparent activation energies used in the model are distributed to correspond with the changing distributions of bond strengths as the species evolve. A normal distribution of the activation energies with the width σ is used for calculations. The coal structure-dependent parameters entering the model and determined from experiments with the respective coals are on the basis of normalized site populations. (α + 1) is the coordination number of a site in the coal lattice and determined from NMR data and is used for calculating mBr/msite.

7.2.2.5 Coupling to heat transport

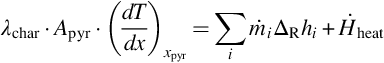

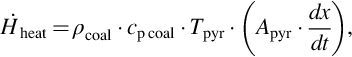

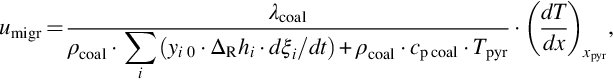

Heat flux into the pyrolysis zone, extension and location of the pyrolysis zone, evolution rate of volatiles as well as migration rate of the pyrolysis zone adjust interdependently to variations of the content and evolution of volatiles in the coal. Detailed calculations need the solution of the nonstationary energy and mass balances in the pyrolysis zone. However, an energy balance for a surface of reaction in the pyrolysis zone can be drafted, which relates the most prominent heat fluxes, namely, the entire heat of reaction  for the endothermic pyrolysis reactions, the heating of the solid and the energy provided by heat conduction into the surface of reaction in the pyrolysis zone

for the endothermic pyrolysis reactions, the heating of the solid and the energy provided by heat conduction into the surface of reaction in the pyrolysis zone

with

where  is the overall heat of reactions of the devolatilization for the single components i and

is the overall heat of reactions of the devolatilization for the single components i and  is the temperature gradient at the surface of reaction. Replacing

is the temperature gradient at the surface of reaction. Replacing  by the rate expressions from Eq. (7.34) we obtain an estimate for the migration rate of the surface of reaction

by the rate expressions from Eq. (7.34) we obtain an estimate for the migration rate of the surface of reaction

where yi 0 is the ultimate mass fraction of the volatile i in the coal, see Table 7.5. The migration rate increases with increasing temperature gradient and heat conductivity of the coal and decreases with increasing energy requirements from the devolatilization reactions. For depleting sources for the volatiles, the migration rate is determined by the heating rate of the solid.

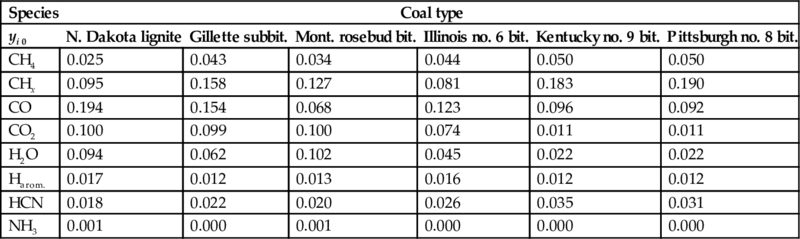

Table 7.5

Ultimate mass fractions yi 0 of different pyrolysis products from different coal types (Solomon et al., 1992)

| Species | Coal type | |||||

| yi 0 | N. Dakota lignite | Gillette subbit. | Mont. rosebud bit. | Illinois no. 6 bit. | Kentucky no. 9 bit. | Pittsburgh no. 8 bit. |

| CH4 | 0.025 | 0.043 | 0.034 | 0.044 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

| CHx | 0.095 | 0.158 | 0.127 | 0.081 | 0.183 | 0.190 |

| CO | 0.194 | 0.154 | 0.068 | 0.123 | 0.096 | 0.092 |

| CO2 | 0.100 | 0.099 | 0.100 | 0.074 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| H2O | 0.094 | 0.062 | 0.102 | 0.045 | 0.022 | 0.022 |

| Harom. | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| HCN | 0.018 | 0.022 | 0.020 | 0.026 | 0.035 | 0.031 |

| NH3 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Due to the temperature gradient in the pyrolysis zone the pyrolysis reactions occur at higher temperatures at the hot end of the pyrolysis zone and at lower temperatures at the cold end of the pyrolysis zone. The different temperature dependency of the formation reactions of the single gaseous and liquid pyrolysis products (see Fig. 7.5 and Table 7.2) and the different ultimate amounts mi 0 of the single components cause a varying product distributions in the pyrolysis zone with time and from the hot side to the cold side.

The time change of the molar amounts of volatiles per volume of the pyrolysis zone which represents a reaction rate for the pyrolysis reactions follows rate expressions as given in Eq. (7.34) and is coupled to the temperature gradient at the surface of reaction in the pyrolysis zone. If  is controlled by diffusion of the components in the porous structure of the coal, compare Eq. (7.28), the migration rate is adapted accordingly, see discussion in Section 7.2.1.

is controlled by diffusion of the components in the porous structure of the coal, compare Eq. (7.28), the migration rate is adapted accordingly, see discussion in Section 7.2.1.

7.2.3 Gasification kinetics

Pyrolysis products formed in the pyrolysis zone as well as water from the wet and drying zones enter conversely to the heat flux into the gasification zone. The large differences in the rate coefficients for the formation of the single components, compare Tables 7.2 and 7.3, spread the evolution of the single pyrolysis products over temperature and time. At temperatures of about 500°C the rate coefficient for the first-order reaction of formation of CO2 is three orders of magnitude larger than that of formation of water, and about five orders of magnitude larger than those of formation of CH4, C2H6, NH3, and tar. The rate coefficients for formation of H2 and HCN are even lower. Therefore, the formation of CO2 and H2O occurs at comparatively low temperatures and at high reaction rates compared with the formation of the other pyrolysis products. However, the increase of temperature in the gasification zone and the large time scale of the overall process finally cause the evolution of the pyrolysis products according to the ultimate amount of the component mi 0 in the coal. This source of the different pyrolysis products in terms of the ultimate mass fractions of the volatiles in the coal yi 0 is given in Table 7.5 for different types of coal (Solomon et al., 1992).

Table 7.5 exhibits vast variations in the ultimate mass fractions of the different pyrolysis products depending on the coal type. However, the most abundant components from pyrolysis of coal are H2O, CH4, CO, CO2, and aliphatic hydrocarbons. The chemical reactions of these components with char (C) are solid/gaseous heterogeneous reactions with the depletion of the solid phase. Coincidentally, the solid phase offers a highly porous structure with changing morphology. Therefore, the gasification reactions may interfere with transport processes to the reacting surface of the solid and the kinetics of gasification are dependent on the morphology of the char. Furthermore, the solid phase can be consumed via different char particle conversion mechanisms.

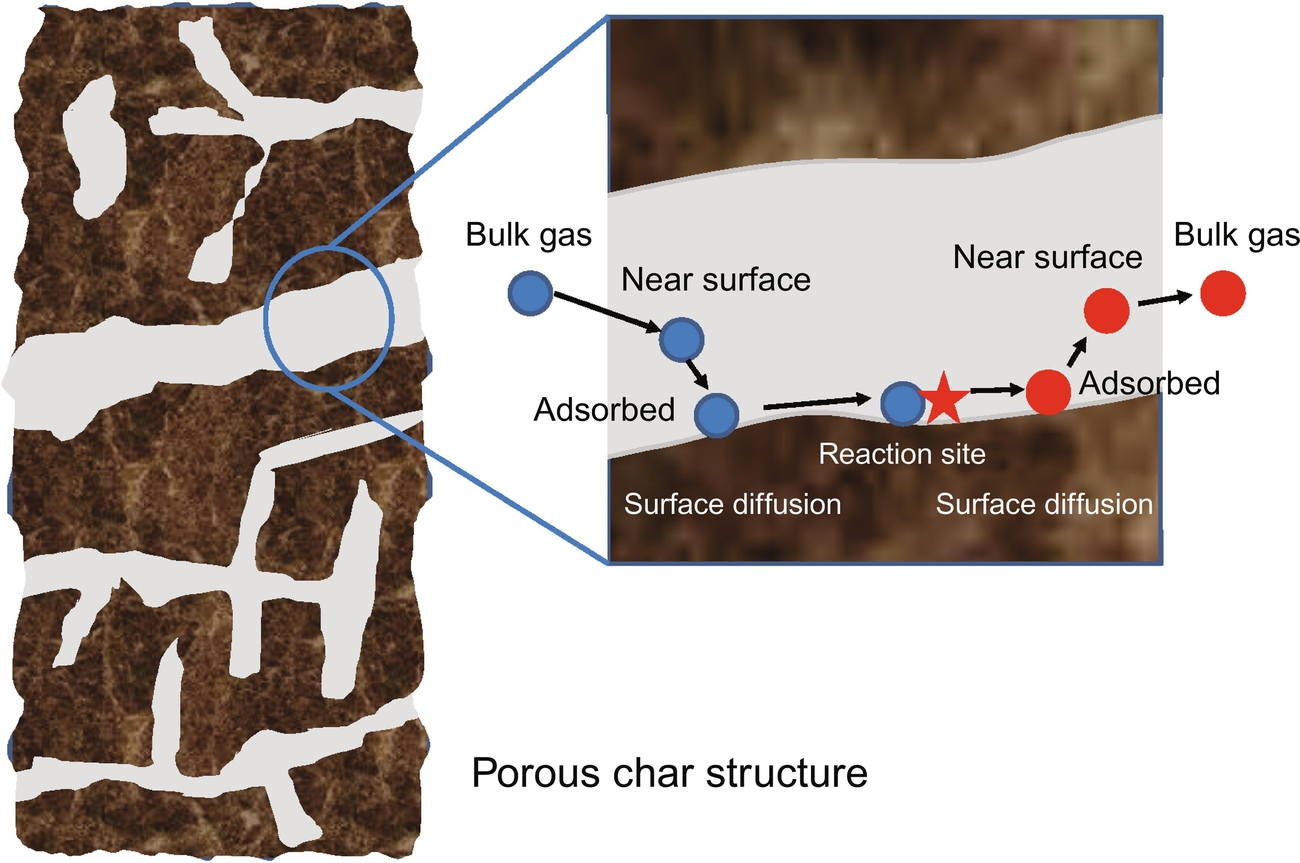

Generally, a heterogeneous reaction occurs via a sequence of steps as depicted in Fig. 7.7:

1. The reactant gases move to the solid surface due to fluid flow and diffusion.

2. The reactant gases adsorb on the solid surface.

3. The reactant gases surface diffuse from the adsorption site to the reaction site depending on the reaction mechanism.

4. The adsorbed gases and the solid react at the reaction sites.

5. The product gases surface diffuse from the reaction site to the desorption site depending on the reaction mechanism.

6. The product gases desorb from the solid surface.

7. The product gases move into the bulk gas due to fluid flow and diffusion.

Possibly, one of these steps is substantially slower than the other steps becoming the rate-limiting step that controls the overall reaction rate and the remaining steps then being nearly at equilibrium. While steps 1 to 3 and 5 to 7 of the earlier scheme are driven by transport processes rather than revealing differences due to the chemical nature, step 4 includes all the chemistry of the reactions of the most abundant species with char. These reactions are discussed in the following in more detail before discussing the transport-driven processes.

7.2.3.1 Kinetic description

A kinetic description of the char-gas reactions requires the detailed consideration of the interactions between gas and solid. The gasification of char formed in pyrolysis is characterized by the porous structure of the char and by variations in time and space of the local gas composition. The local heterogeneous reaction rate at any surface within the char is determined by the local concentration of the gaseous components and the different steps in the reaction sequence sketched in Fig. 7.7. Reaction rate expressions such as Eq. (7.5) have to be extended according to the appropriate occurring elementary mechanisms. The reaction site concept is employed for this.

The concept of reaction sites assumes the reactions occurring at favored sites on the surface. The nature of such sites may be carbon edges or dislocations, carbon atoms in vicinity to oxygen, hydrogen, and other functional groups, radicalic sites or inorganic components contained in the coal (see Fig. 7.4). These surface irregularities result in comparatively strong interaction forces, which induce electron transfer causing gas-solid bonding or chemisorption. At each reaction site, adsorption (chemisorption) of reactants, migration of intermediates, reaction, and product desorption may take place via single site or dual site mechanism.

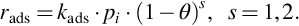

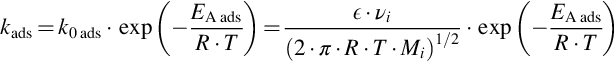

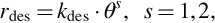

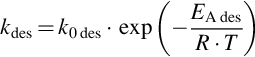

For the formulation of rate expressions few more assumptions are necessary (Hayward and Trapnell, 1964; Frank-Kamenetzkii, 1969). The surface is supposed to be homogeneous with a uniform distribution of reaction sites, that is, a uniform average activity can be defined for the entire surface. Adsorption occurs localized via collisions with vacant reaction sites. There is only one adsorbed molecule or atom per site due to strong valence bonds. The surface coverage may not exceed a complete monomolecular layer and the mechanism of chemisorption/migration/desorption is not changing. No interaction occurs among adsorbed species, that is, the amount of adsorbed species has no effect on the adsorption rate per site. Chemisorption arises from gas molecules striking the surface at locations not covered by previously adsorbed species. If θ is the fraction of reaction sites covered by adsorbed species Nads/Nreact, the intrinsic rate of adsorption of a species i is

Here s denotes single and dual site adsorption. From kinetic theory of gases

is obtained, with ϵ the collision effectivity and νi a stoichiometric factor. Similarly, for desorption

with

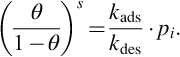

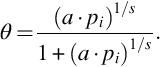

can be written. Assuming steady-state and locally isothermal conditions, rads = rdes resulting in

Under the earlier assumptions kads/kdes = a is solely a function of temperature T and independent of surface coverage θ. From Eq. (7.47) the surface coverage can be deduced:

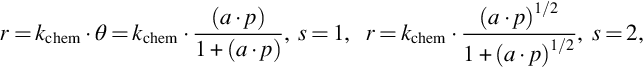

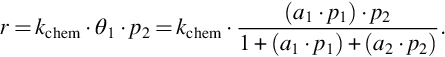

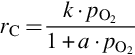

Setting now s = 1 and assuming the rate determining step will be adsorption or desorption, the intrinsic surface reaction rate becomes (Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics)

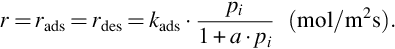

Eq. (7.49) exhibits the general characteristics of heterogeneous reaction rates based on the reaction site approach. For a ⋅ pi ≤ 1 the apparent order of the reaction is 1 and the reaction rate is linearly dependent on the partial pressure pi. For increasing pi the order of reaction decreases until for a ⋅ pi ≫ 1, at complete coverage of the reaction sites, a reaction order of 0 with a constant reaction rate is attained. This holds also for s = 2. Eq. (7.49) also exhibits that the reaction rate for heterogeneous reactions in contrast to Eq. (7.4) is given as time change of the molar amounts per unit surface area of the solid, mol/(m2 s). Considering multicomponent adsorption, which is most probable taking into account the composition of the gaseous mixture evolving from the pyrolysis zone, the balance rads = rdes for multicomponent adsorption

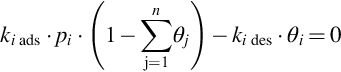

for the example of a binary system and single site reactions leads to

The Langmuir-Hinshelwood kinetics for species 1 then is given by

Accordingly, an analogous rate expression holds for species 2. Eq. (7.52) reveals that the reaction is inhibited by the adsorption of species 1 and, if or if not species 2 is a reactant, by the adsorption of this species. This is another characteristic of heterogeneous reactions.

For surface reactions or surface migration being the rate determining steps a variety of kinetic expressions arise. For the conversion of an adsorbed species we obtain

where kchem means the rate coefficient for the chemical reaction or surface migration. If reactant species 2 from the gas phase reacts with adsorbed species 1 in a one site reaction, the reaction rate is given by

We see from Eqs. (7.52)–(7.54) that different molecular mechanisms of the heterogeneous reaction—chemisorption, surface migration, surface reaction—lead to similar rate expressions. However, they all are characterized by a change in reaction order with increasing reactant partial pressure and inhibition by inert components, reactants, and even products. This provides a further answer to the question raised in Section 7.1.1 and points out that for the kinetics of coal gasification no unique chemical reaction mechanisms and unique rate expressions comparable to homogeneous chemical reactions are to be derived.

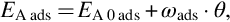

For the Langmuir isotherms a homogeneous noninteracting surface has been assumed resulting in constant activation energies. However, the surface of char is nonhomogeneous and due to the nature of the sites, they exhibit different activity for adsorption and different reactivity. The most active sites are covered first and for an interacting surface covering of adjacent sites creates repulsion forces inhibiting adsorption and promoting desorption of following molecules. Consequently, the activation energy for adsorption increases and the one for desorption decreases with increasing surface coverage θ. An expression for the activation energy reflecting the interactions would be

where EA 0 ads means the activation energy at θ→0 and ωads a surface energy constant. The adsorption rate exhibits an exponential decrease according to

The different nature of the sites with respect to reactivity can also be considered by using a distribution of the activation energies, see Section 7.2.2.3.

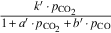

7.2.3.2 Surface reactions of water with char

Water formed in the pyrolysis zone and entering from the wet and drying zone reacts with char according to the formal reaction

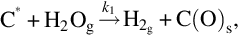

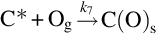

which is endothermic at 500°C by about 135 kJ/mol C. Following the reaction site approach the reaction is supposed to proceed on a molecular level via a single-site reaction mechanism according to (see Laurendeau, 1978; Roberts and Harris, 2006)

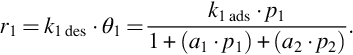

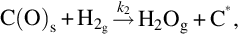

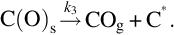

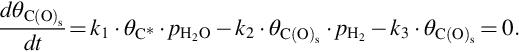

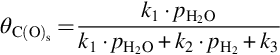

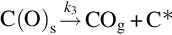

Here C⁎ means a free carbon site in the char structure accessible for reaction and C(O)s means a carbon site filled with atomic oxygen. The gasification is initiated by the attack of H2O from the gas phase at a reaction carbon site C⁎ releasing H2 into the gas phase and leaving an O in the carbon site. The reaction occurs also in the opposite direction. Mass loss of char is given by the transport of carbon atoms from the solid into the gas phase occurring through the elimination of CO from the C(O)s sites recovering free reaction sites C⁎. The rate of molar loss of carbon from char is given by

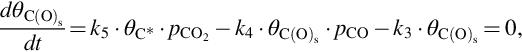

where Nreact the total number of reaction sites. For the net formation rate of the C(O)s sites the assumption of quasisteady state is introduced, hence

Using  we obtain

we obtain

and

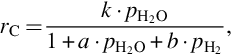

where k = Nreact ⋅ k1, a = k1/k3, and b = k2/k3. The rate of molar carbon loss from the solid phase, Eq. (7.64), exhibits the typical characteristics for heterogeneous reactions, namely change of the reaction order with increasing partial pressure of H2O and inhibition by the educt and product through oxygen exchange.

For high partial pressures of CO and particularly at temperatures above about 1200°C, CO2 appears as a secondary product via the reaction (von Fredersdorf and Elliott, 1963; Ergun, 1961)

which proceeds also in the reverse direction

Together with the steam gasification reactions water-gas equilibrium may be attained at temperatures high enough. If as earlier steady-state approximations are introduced for C(O)s, the reaction rate for the molar loss of carbon from char can be written as

Eq. (7.67) illustrates the inhibition of the rate of carbon loss from char by CO, H2, and CO2 in addition to the educt H2O.

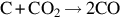

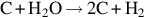

7.2.3.3 Surface reactions of carbon dioxide with char

Carbon dioxide formed to a large extent during devolatilization reacts with char according to the formal reaction

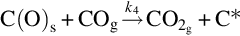

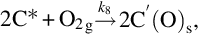

which is endothermic at 500°C by about 172 kJ/mol C. Adopting the reaction site approach the reaction on a molecular scale proceeds via (Ergun, 1961; Mentser and Ergun, 1973; Strange and Walker, 1976)

and finally

As for gasification with H2O the gasification is initiated by the attack of CO2 from the gas phase at a reaction carbon site C⁎ releasing CO into the gas phase and leaving an O in the carbon site. This reaction occurs also in the opposite direction. Finally, CO evolves from the C(O)s sites recovering free reaction sites C⁎. The two first reactions have been introduced as side reactions occurring during the gasification by H2O and the last reaction presents also the final step in the gasification by H2O. For the formation of gaseous CO two sources exist in that reaction scheme; however, the rate of molar loss of carbon from char is the same as in the gasification by H2O, see Eq. (7.61). The net formation rate of C(O)s sites applying quasisteady-state assumptions in this case is given by (see Eqs. 7.69–7.71)

which gives introducing

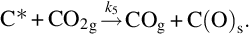

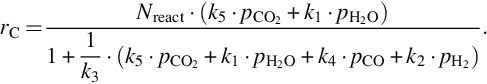

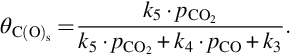

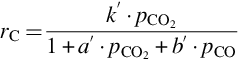

For the rate of molar carbon loss from the char we obtain

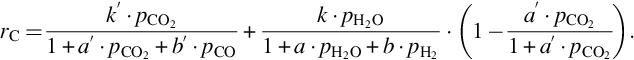

where k′ = Nreact ⋅ k5, a′ = k5/k3, and b′ = k4/k3. The rate for molar carbon loss from the solid phase, Eq. (7.74), again exhibits the typical characteristics for heterogeneous reactions: change of the reaction order with increasing partial pressure of CO2 and inhibition by the educt and product. It should be noted that the inhibition of the gasification reaction is not by adsorption as in the pure Langmuir-Hinshelwood approach, but rather via oxygen exchange at oxygen-filled reaction sites. It should also be noted that the gasification rate in presence of CO2 and H2O is not just the sum of the reaction rates Eq. (7.74) plus Eq. (7.64), but CO2 and H2O compete for the same reaction sites. Adsorption of H2O is blocked by preadsorbed CO2. Therefore, the rate of gasification by H2O is reduced in presence of CO2. Because the gasification rate by H2O is much faster than the gasification rate by CO2, the reverse is not the case. The rate equation for gasification by H2O/CO2 mixtures is given by (Roberts and Harris, 2007)

According to Eqs. (7.64), (7.74) the rate of molar carbon loss from char is proportional to the total number of reaction sites Nreact. The total number of reaction sites varies extremely among the chars from the different kinds of coal. Therefore, the prediction of the rate of carbon loss is impossible without the knowledge of that number even if reliable values for the different rate coefficients are available. If, however, the total number of reaction sites is responsible for the variations in the gasification rate, the temperature dependency of the individual steps can be obtained independently of the coal type so that the activation energies of the different reactions can be measured independently of the coal type.

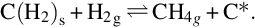

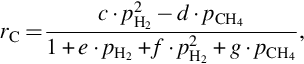

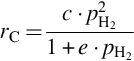

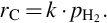

7.2.3.4 Surface reactions of hydrogen with char

Hydrogen is formed during devolatilization of coal at very low reaction rates, see Table 7.2 and to little extent, see Table 7.5. Therefore, gasification of char via the global reaction

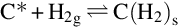

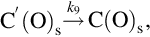

which is exothermic at 500°C by about 86 kJ/mol C contributes only little to the gasification of coal by formation of CH4. The major part of CH4 is formed during devolatilization. The surface mechanism seems to be complex because the product with five atoms appears not to be formed in single site reactions as in the case of gasification with H2O or CO2. A reaction scheme (Blackwood, 1962) starts with the adsorption of molecular H2

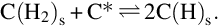

followed by the dissociation of adsorbed H2

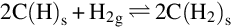

The sites filled with H-atoms incorporate further H-atoms from H2 in the gas phase

and are finally converted with further H2 from the gas phase to CH4

From this reaction scheme with reversible single reactions a typical heterogeneous rate expression for the gasification to CH4 can be deduced:

which collapses for low CH4 partial pressures to

and for high hydrogen partial pressures present in the final state of gasification to a reaction being of first order in hydrogen partial pressure

Eqs. (7.81)–(7.83) and likewise Eqs. (7.64), (7.74) provide gasification rates for a well-defined state in terms of temperature, pressure, and partial pressures of reactants and products. However, the rate equations also emphasize the particular problems of reaction kinetics in underground coal gasification: underground coal gasification is a zonal process with changes of state in time and space. Therefore, also reaction kinetics and mechanisms change in time and space and the rates for gasification reactions vary in magnitude and order and, therefore, product composition.

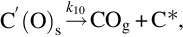

7.2.3.5 Surface reactions of oxygen with char

The necessary reaction energy for the overall endothermic gasification of coal as well as the necessary energy for vaporization and devolatilization has to be provided and balanced by combustion of a part of the char according to

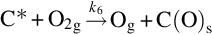

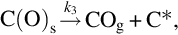

The reaction is exothermic at 800°C by about 395 kJ/mol C and apparently very fast compared with the gasification reactions discussed earlier. For typical combustion temperatures reaction schemes based on the reaction site concept involving the dissociative adsorption of O2 (Nagle and Strickland-Constable, 1962; von Fredersdorf and Elliott, 1963; Spokes and Benson, 1967) end in the formation of CO and attribute the formation of CO2 to the homogeneous reaction  :

:

and thermal annealing of reaction sites to inactive sites occurring at high temperatures

The dissociative adsorption of O2 in contrast to the oxygen exchange by H2O and CO2 is supposed to be nonreversible. Omitting reaction (7.88) and applying steady-state assumptions for C(O)s a rate expression for the gasification is obtained

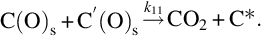

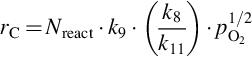

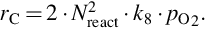

where k = Nreact ⋅ k6, a = k6/k3, which exhibits apparent reaction orders between 0 and 1 depending on the partial pressure of O2 typical for heterogeneous reaction rates. Though the rate expression describes observed reaction rates well the rapid formation of CO2 even at low temperatures cannot be reproduced. An extension of this reaction scheme introducing two-site adsorption of oxygen (Laurendeau, 1978) accounts also for the formation of CO2 in a heterogeneous step:

Here C′(O)s represents a mobile site. Applying steady-state assumptions for the two kinds of sites C(O)s and C′(O)s and introducing estimations for the relative rates at the different temperature ranges and ranges of partial pressures of O2 (Laurendeau, 1978), rate expressions of different apparent reaction order can be developed. For low temperatures

with an apparent reaction order μapp = 0 results, where the desorption from the mobile sites is rate determining. For intermediate temperatures

is obtained, where the apparent reaction order μapp = 1/2 and site migration is rate determining. Finally, for high temperatures a reaction order μapp = 1 is attained and the dissociative adsorption of O2 is rate determining

7.2.3.6 Reaction rate coefficients

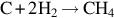

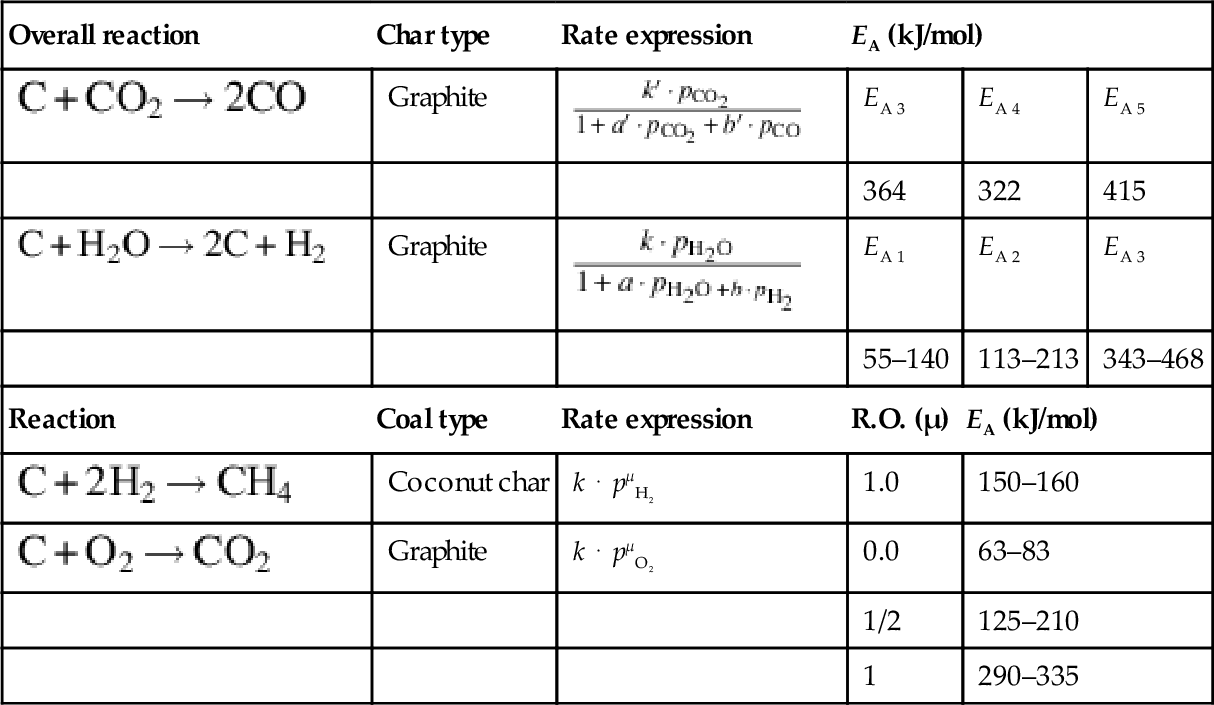

As pointed out earlier the rate laws given in Eqs. (7.64), (7.67), (7.74), (7.81)–(7.83), or (7.95)–(7.97) all contain the number of reaction sites Nreact of the char which may be different by orders of magnitudes for chars of different origin. Therefore, any compilation or comparison of kinetic data for coal gasification should refer to comparable Nreact or at least to char with comparable specific surface area (see e.g., Laurendeau, 1978 for a detailed discussion). For the same reason rate coefficients for global reaction rates may be applied only for the same reaction conditions and char types that have been investigated for the evaluation of the rate coefficients. The coal-type independent parts of some rate coefficients for the gasification reactions discussed earlier are collected in Table 7.6. More data and ample discussion is given in Laurendeau (1978), Müllen et al. (1985), Roberts and Harris (2000), Kajitani et al. (2006), and Bell et al. (2011).

Table 7.6

Reaction rate parameters for gasification reactions of char

| Overall reaction | Char type | Rate expression | EA (kJ/mol) | ||

| Graphite |  | EA 3 | EA 4 | EA 5 |

| 364 | 322 | 415 | |||

| Graphite |  | EA 1 | EA 2 | EA 3 |

| 55–140 | 113–213 | 343–468 | |||

| Reaction | Coal type | Rate expression | R.O. (μ) | EA (kJ/mol) | |

| Coconut char | k ⋅ pμH2 | 1.0 | 150–160 | |

| Graphite | k ⋅ pμO2 | 0.0 | 63–83 | |

| 1/2 | 125–210 | ||||

| 1 | 290–335 | ||||

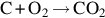

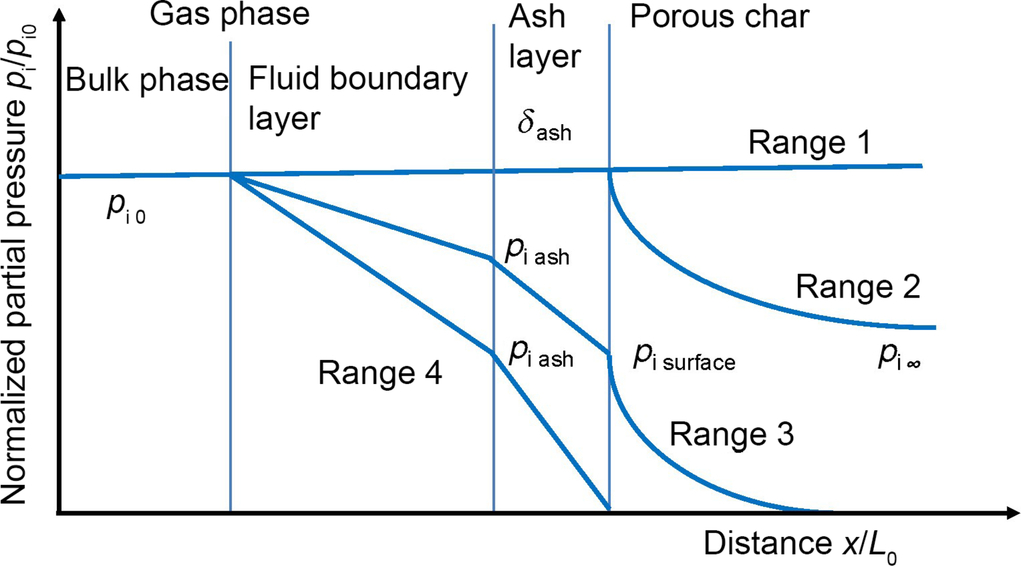

7.2.3.7 Coupling to mass transport

Table 7.6 illustrates that the rate coefficients for the gasification reactions exhibit different and comparably strong dependencies on temperature. Furthermore, the discussion of the different rate expressions clarified that the mechanism of the heterogeneous gasification reactions may change due to the changing composition and temperature of the gas phase. Altogether, this can cause a change in the rate determining steps illustrated in Fig. 7.7. A schematic of the effect of a variation in the rate determining steps is given in Fig. 7.8 (see also Emig and Dittmeyer, 1997).

Considering a porous char layer covered by an ash layer, compare Fig. 7.2, the reactant partial pressure within and outside the porous solid phase depends on the intrinsic reaction rate. At low temperatures where the intrinsic reaction rate is low mass transfer and diffusion rates are sufficient large producing an essentially constant reactant partial pressure profile throughout the solid phase and the adjacent fluid boundary layer. In this case the overall reactivity will be controlled by the intrinsic heterogeneous reaction rate (range 1 in Fig. 7.8). With increasing intrinsic reaction rate, the diffusion rate within the porous structure and at higher reaction rates even through the ash layer and the fluid boundary layer cannot keep up with the chemical reaction rate. Hence, the partial pressure profiles develop as indicated by range 2 and range 3. As can be seen from the schematic diagram in Fig. 7.8 less and less of the solid porous char phase volume becomes accessible to high gas concentrations. For range 4 the chemical reaction within the pore structure is so rapid compared with diffusion that the reactant gas concentration approaches zero both within and at the surface of the porous solid. In this case the overall reaction rate is controlled solely by diffusion across the ash layer and fluid boundary layer. The physical reason for this pattern is the different temperature dependency of diffusional transport (see Eqs. 7.29, 7.30) and chemical reaction rates (see Eq. 7.7).

To provide a closer look into the kinetics under these circumstances the overall reaction rates for the different ranges depicted in Fig. 7.8 may be discussed. For range 1, the intrinsic kinetics is rate limiting, so that the overall reaction rate is given by one of the rate expressions from Eqs. (7.64), (7.67), (7.74), (7.81)–(7.83), or (7.95)–(7.97). This approach is assigned volume reaction models or modified volume reaction models (Zogala, 2014). For utilizing this kind of models correlations for the number of reaction sites with the total volume/total external surface must be available.

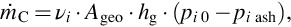

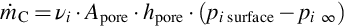

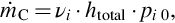

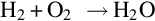

For the other ranges indicated in Fig. 7.8 the overall reaction rate is determined by the molar fluxes of the reactants into the porous solid caused by mass transfer and diffusion. For the fluid boundary layer we obtain with this using the integrated form of Fick's law

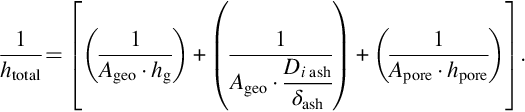

where νi represents a stoichiometric factor for the gasification reaction, Ageo is the geometric surface area, hg is the mass-transfer coefficient for the prevailing conditions (Ghiaasiaan, 2014), and pi 0 and pi ash are the reactant partial pressures at the bulk gas phase/fluid boundary layer and fluid boundary layer/ash layer, respectively. Proceeding to the ash layer the overall reaction rate is given similarly by applying Fick's law

which gives after integration

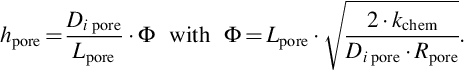

Here Di ash is the effective diffusion coefficient of the reactant in the ash layer, δash is the thickness of the ash layer, and pi surface is the partial pressure of the reactant at the surface of the solid porous char phase. Finally, for the diffusion into the porous structure

can be written, where Apore are the cross-sectional areas of all pores, hpore is the mass-transfer coefficient for the diffusional mass transport into the pores, and  is the reactant partial pressure at the pore end. It should be noted that for Apore a correlation with the geometric area or volume of the char must be provided and that the mass-transfer coefficient is a complicated function of the diffusion mechanism within the pores, the structure of the pores (tortuosity), pore size (Knudsen number), and the type of surface reaction. Assuming for simplicity cylindrical pores and molecular diffusion and a reaction of first order with respect to the reactant, which may be suitable for a wide range of reaction conditions (see reaction rate expressions discussed in Sections 7.2.3.1–7.2.3.5) and

is the reactant partial pressure at the pore end. It should be noted that for Apore a correlation with the geometric area or volume of the char must be provided and that the mass-transfer coefficient is a complicated function of the diffusion mechanism within the pores, the structure of the pores (tortuosity), pore size (Knudsen number), and the type of surface reaction. Assuming for simplicity cylindrical pores and molecular diffusion and a reaction of first order with respect to the reactant, which may be suitable for a wide range of reaction conditions (see reaction rate expressions discussed in Sections 7.2.3.1–7.2.3.5) and

Φ is the Thiele modulus for the specified assumptions. For other conditions as specified by the earlier assumptions the Thiele modulus attains different forms and, hence, the mass-transfer coefficient for the diffusion into the pores (Crank, 1964). Combining Eqs. (7.98), (7.100), (7.101) to eliminate the unknown partial pressures at the internal boundary surfaces, we obtain

where

With this simplified approach we treat the overall molar flux, which is equivalent to a reaction rate given by the time change of the molar amounts of carbon, in terms of a series of mass-transfer resistances which add to a total resistance. Eq. (7.104) clearly reveals that the process with the highest resistance dominates the overall reaction rate. It should be noted that this approach may be extended referring to the statistical structure of the porous char and the appropriate mechanisms of surface reactions and pore diffusion. However, the principle characteristic of the overall reaction rate with the superposition of the different transport processes, affecting the surface reaction, is reflected by Eqs. (7.103), (7.104). Further discussion is presented in Laurendeau (1978) and Bell et al. (2011).

The combustion of char via reaction (7.84) provides to the largest part the energy necessary for the other endothermic gasification reactions (7.57), (7.68) as well as for devolatilization and drying. Combustion and gasification reactions consume the solid phase so that the char gasification zone migrates through the coal seem. The migration rate may be estimated with the help of energy balances as sketched in Section 7.2.2.5 introducing the appropriate reaction rates and temperatures. The heat fluxes from the gasification zone into the pyrolysis zone and further into the drying zone, extension and location of the different zones, evolution rate of gasification products and volatiles as well as migration rates of the zones adjust interdependently to variations of the local state and conditions as discussed in Sections 7.2.1 and 7.2.2.5.

7.2.4 Homogeneous secondary reactions of gasification and pyrolysis products

The intended product of underground gasification is a mixture of CO and H2. According to the composition of coal, the content of volatiles, and the amount of water the required energy for drying, devolatilization and gasification necessitates the combustion of varying amounts of coal so that the product gas contains a certain level of CO2. Products from devolatilization and pyrolysis can also survive the gasification zone, because air/oxygen is not applied in excess. Typical gas composition from underground gasification is given in Table 7.7 (Bell et al., 2011, see also Perkins and Sahajwalla, 2008).

Table 7.7

Typical product gas composition on a dry basis in % by volume from underground coal gasification (Powder River Basin, Wyoming)

| Component | Air-blown | O2-blown |

| CH4 | 5.4 | 10.6 |

| C2H6 + C2H4 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| C4H8+C3H6 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| CO | 16.1 | 31.5 |

| CO2 | 11.8 | 23.1 |

| H2 | 16.7 | 32.7 |

| N2 | 48.8 | – |

The product gas components constitute a highly combustible mixture which reacts with oxygen via homogeneous reactions, for example

and also among each other via, for example

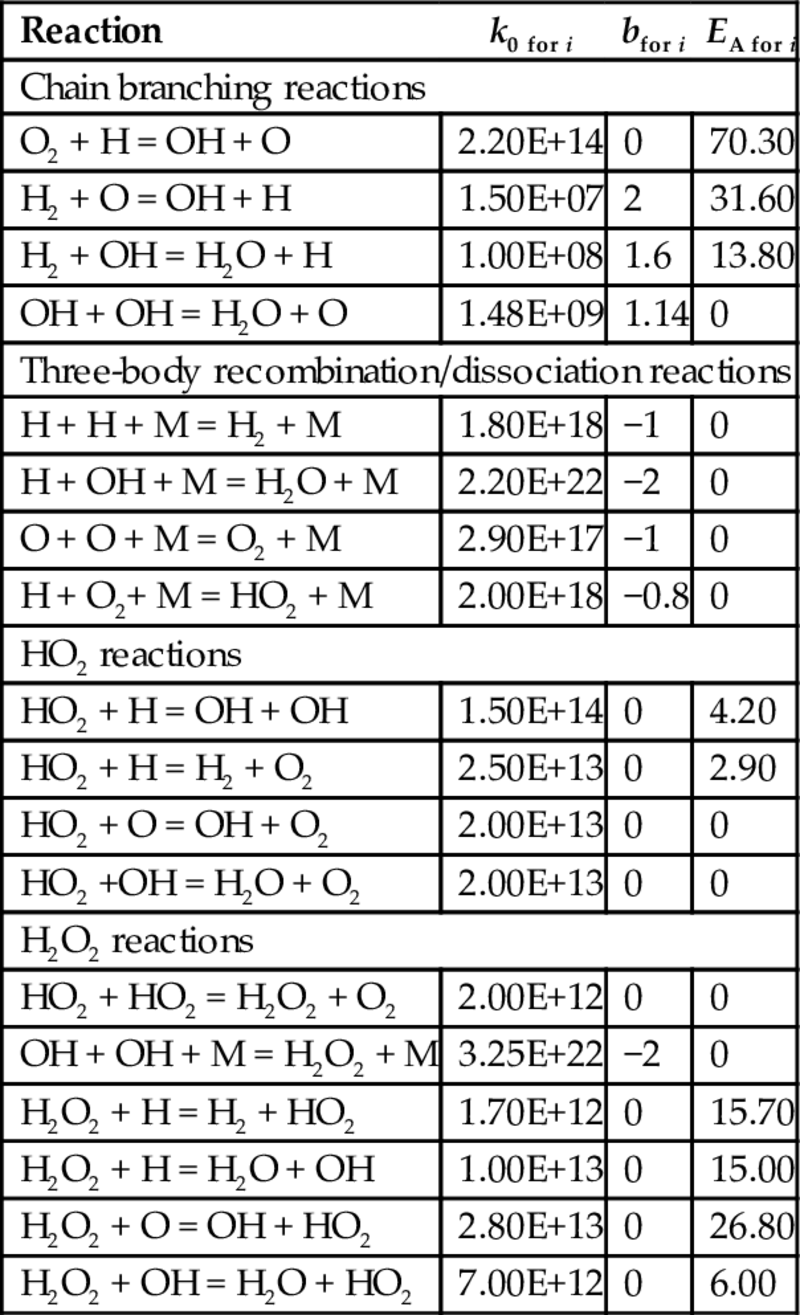

The earlier-listed homogeneous combustion and gasification reactions occur via complex mechanism of parallel and consecutive reactions including radical chain initiation, chain propagation, and chain branching reactions. An example for this kind of mechanism for the combustion of H2 according to reaction (7.106) is given in Table 7.8 (Maas and Warnatz, 1988). The reactions listed in Table 7.8 take place in forward and reverse directions. The rate coefficients for the reverse reactions can be calculated from thermodynamic data. Reaction mechanisms for the combustion and gasification of CO and hydrocarbons, comprising several hundreds of elementary reactions between large numbers of species, can be found in the literature, see for example, Gardiner (2000), Battin-Leclerc et al. (2013), and Smith et al. (2017).

Table 7.8

Reaction mechanism and reaction rate coefficients for the combustion of H2 (Maas and Warnatz, 1988)

| Reaction | k0 for i | bfor i | EA for i |

| Chain branching reactions | |||

| O2 + H = OH + O | 2.20E+14 | 0 | 70.30 |

| H2 + O = OH + H | 1.50E+07 | 2 | 31.60 |

| H2 + OH = H2O + H | 1.00E+08 | 1.6 | 13.80 |

| OH + OH = H2O + O | 1.48E+09 | 1.14 | 0 |

| Three-body recombination/dissociation reactions | |||

| H + H + M = H2 + M | 1.80E+18 | −1 | 0 |

| H + OH + M = H2O + M | 2.20E+22 | −2 | 0 |

| O + O + M = O2 + M | 2.90E+17 | −1 | 0 |

| H + O2+ M = HO2 + M | 2.00E+18 | −0.8 | 0 |

| HO2 reactions | |||

| HO2 + H = OH + OH | 1.50E+14 | 0 | 4.20 |

| HO2 + H = H2 + O2 | 2.50E+13 | 0 | 2.90 |

| HO2 + O = OH + O2 | 2.00E+13 | 0 | 0 |

| HO2 +OH = H2O + O2 | 2.00E+13 | 0 | 0 |

| H2O2 reactions | |||

| HO2 + HO2 = H2O2 + O2 | 2.00E+12 | 0 | 0 |

| OH + OH + M = H2O2 + M | 3.25E+22 | −2 | 0 |

| H2O2 + H = H2 + HO2 | 1.70E+12 | 0 | 15.70 |

| H2O2 + H = H2O + OH | 1.00E+13 | 0 | 15.00 |

| H2O2 + O = OH + HO2 | 2.80E+13 | 0 | 26.80 |

| H2O2 + OH = H2O + HO2 | 7.00E+12 | 0 | 6.00 |

Notes: The rate coefficients are given as  for forward reactions only. The rate coefficients for the reverse reactions can be calculated from thermodynamic data. Units are mole, s, and kJ/mol.

for forward reactions only. The rate coefficients for the reverse reactions can be calculated from thermodynamic data. Units are mole, s, and kJ/mol.

Reaction rates for this part of the underground gasification process consisting of homogeneous reactions can be expressed as outlined briefly in Section 7.1.1. Referring to Eq. (7.5) the forward reaction rate for a single reaction j of species i can be written as

As the reactions listed in the mechanism given in Table 7.8 are elementary reactions, the reaction order with respect to the single reactants is the respective stoichiometric coefficient. An analogous expression holds for the backward reaction and the net reaction rate of species i in reaction j then is given by

The conversion of the single components i in this kind of multireaction system is given by the sum of the reaction rates of all the single reactions where the specific component is involved in