Underground coal gasification (UCG) modeling and analysis

M.A. Rosen; B.V. Reddy; S.J. Self University of Ontario Institute of Technology, Oshawa, ON, Canada

Abstract

Mining is the typical method of extracting coal, but it can only recover 20%–25% of global coal resources. Mining has many challenges and requires much time, resources, and personnel. A new method of coal extraction, underground coal gasification (UCG), could address some of these problems while greatly expanding recoverable coal resources. Underground coal gasification is a gasification process applied to in situ coal seams. When combined with carbon capture and storage, UCG has significant potential for providing a relatively clean energy source. This chapter reviews key concepts and technologies of UCG, providing insights into this developing coal extraction method. A case study is also presented that illustrates the modeling and analysis of UCG and assesses the feasibility of using an auxiliary power plant and utilizing waste heat rejected syngas processing, to supply the required energy associated with amine-based carbon dioxide capture and compression processes.

Keywords

Underground coal gasification; In situ coal gasification; UCG; Energy; Coal technology; Carbon capture; Carbon dioxide capture; Rankine cycle; Energy analysis; Waste heat recovery

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

10.1 Introduction

The global supply of energy is composed of many sources, including fossil fuels, nuclear fuels, and various alternative and renewable sources. As of 2012, approximately 82% of the global energy supply was derived from fossil fuels, and a continued high fossil-fuel dependency appears likely in the immediate future (García-Olivares and Ballabrera-Poy, 2015; International Energy Agency, 2014; World Energy Council, 2013). The amount of energy required globally is projected to increase due to growing population and industrialization (Birol, 2014; Energy Information Administration, 2014). Birol (2014) estimates that the total global energy use will grow by 40%, relative to levels today, by the year 2040. Given the increases in global energy demand, the current dependence on fossil-fuel technologies, and the finite amount of fossil fuels available, it has been predicted that fossil-fuel shortages will occur in the future (García-Olivares and Ballabrera-Poy, 2015).

Hammond (2000) argues that fossil-fuel depletion is a significant factor for the future when considering sustainable energy systems. Fossil-fuel resources are finite and being consumed rapidly, especially the most economically attractive ones (oil and gas) (Aleklett et al., 2010). Fossil-fuel resource extraction and production rates are expected to peak and begin to decline in the foreseeable future (Chapman, 2014; World Energy Council, 2013; Aleklett et al., 2010). When fossil-fuel demand approaches supply levels, the cost of energy is anticipated to increase drastically, prompting research and technological developments for improved ways to convert more fossil-fuel resources into useable reserves (Ghose and Paul, 2007).

In 2012, coal was the largest source used for electricity generation, accounting for approximately 40% of the world's electricity production (World Energy Council, 2013). Coal exhibits the largest global reserves of any fossil fuels and is abundant in many countries. The world's recoverable coal reserve is estimated at close to 150 years at current production rates, but this only represents only 20%–25% of the entire resource (International Energy Agency, 2014; Birol, 2014; World Energy Council, 2013). Global coal resources have recently been estimated to be 18 trillion tonnes (Couch, 2009), which contrasts significantly with the typical figure of tens of billions of tonnes for recoverable reserves (Birol, 2014). If unrecoverable coal can be shifted to recoverable reserves, the lifetime of the resource could be extended by a couple hundred years. For this to be realized, new economic extraction techniques need to be implemented. Much research related to coal processes and use has been reported (Rosen et al., 2015; Mehmood et al., 2015; Mehmood et al., 2014; Gnanapragasam et al., 2010; Gnanapragasam et al., 2009).

Coal is conventionally extracted by mining, both underground and open pit. Mining operations require much time, personnel, and natural resources. Coal reserves usually lie too deep underground or are too costly to exploit using conventional mining methods. Conventional mining also has other challenges including land subsidence, high machinery costs, hazardous work environments, coal transport requirements, localized flooding, and methane buildup in cellars of nearby homes (Blinderman, 2015; Bhutto et al., 2013).

Underground coal gasification (UCG) is a newer type of coal extraction that is being investigated and implemented around the world. Underground coal gasification is a combination of mining, exploitation, and gasification that eliminates the need for mining; UCG involves the conversion in situ coal into synthetic gas (syngas) for use in power generation or as chemical feedstock (Brown, 2012). Underground coal gasification can avoid most of the problems of mining coal while expanding recoverable coal reserves (Nakaten et al., 2014). Underground coal gasification limits the amount of underground work required by personnel, lowering risks of harm relative to conventional mining. Power generation and chemical processing plants can be built directly above a coal resource and use the syngas produced through UCG, avoiding coal transport. Underground coal gasification has the ability to significantly widen the resource base, since it permits the energy contained within previously inaccessible coal reserves to be recovered economically (Blinderman, 2015). It has been estimated by the underground coal gasification partnership that around 4 trillion tonnes of otherwise unusable coal could be suitable for UCG (Ghose and Paul, 2007).

UCG is appealing for expanding recoverable coal reserves, but as with the combustion of all fossil fuels, there are associated greenhouse gas emissions. Coal is the most carbon-intensive of all fossil fuels and has high associated CO2 emissions per unit of thermal energy produced (Roddy and Younger, 2010). If coal is to continue to be a major contributor in the future global energy supply, CO2 capture and storage techniques almost certainly need to be incorporated. Underground coal gasification has good potential for CO2 emissions reduction. During gasification, CO2 is produced, which can be captured from the syngas and stored for long terms (Schiffrin, 2015). If UCG is successfully linked to such carbon capture and storage (CCS), a method will be available for exploiting the energy in previously unrecoverable coal reserves while satisfying standards for reducing CO2 emissions.

The aim of this chapter is to review concepts, technologies, and models related to underground coal gasification and carbon capture in UCG systems. This chapter also presents a case study that illustrates the modeling and analysis of UCG and investigates the feasibility of using an auxiliary power plant, utilizing the thermal energy removed during the cooling gasification products, to provide the energy required for CCS, through amine-based chemical absorption and compression within a UCG system. The overall objective of the chapter, which draws heavily from prior work by the authors (Self et al., 2013; Self et al., 2012), is to improve the general understanding of UCG technology and modeling while presenting a method for analyzing UCG systems with CCS.

10.2 UCG processes

UCG is similar to surface gasification with syngas produced through the same chemical reactions (Pana, 2009; Burton et al., 2006). The main difference is that surface gasification occurs in a manufactured reactor, whereas the reactor for a UCG system is a natural geologic formation containing unmined coal (Pana, 2009). Underground coal gasification also has similarities to in situ combustion processes applied in heavy-oil recovery and oil shale retorting, with such common operational parameters as roof/floor stability, seam continuity and permeability, and groundwater influx (Lee et al., 2014; Pana, 2009).

10.2.1 UCG process overview

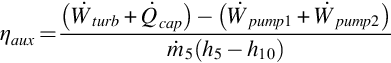

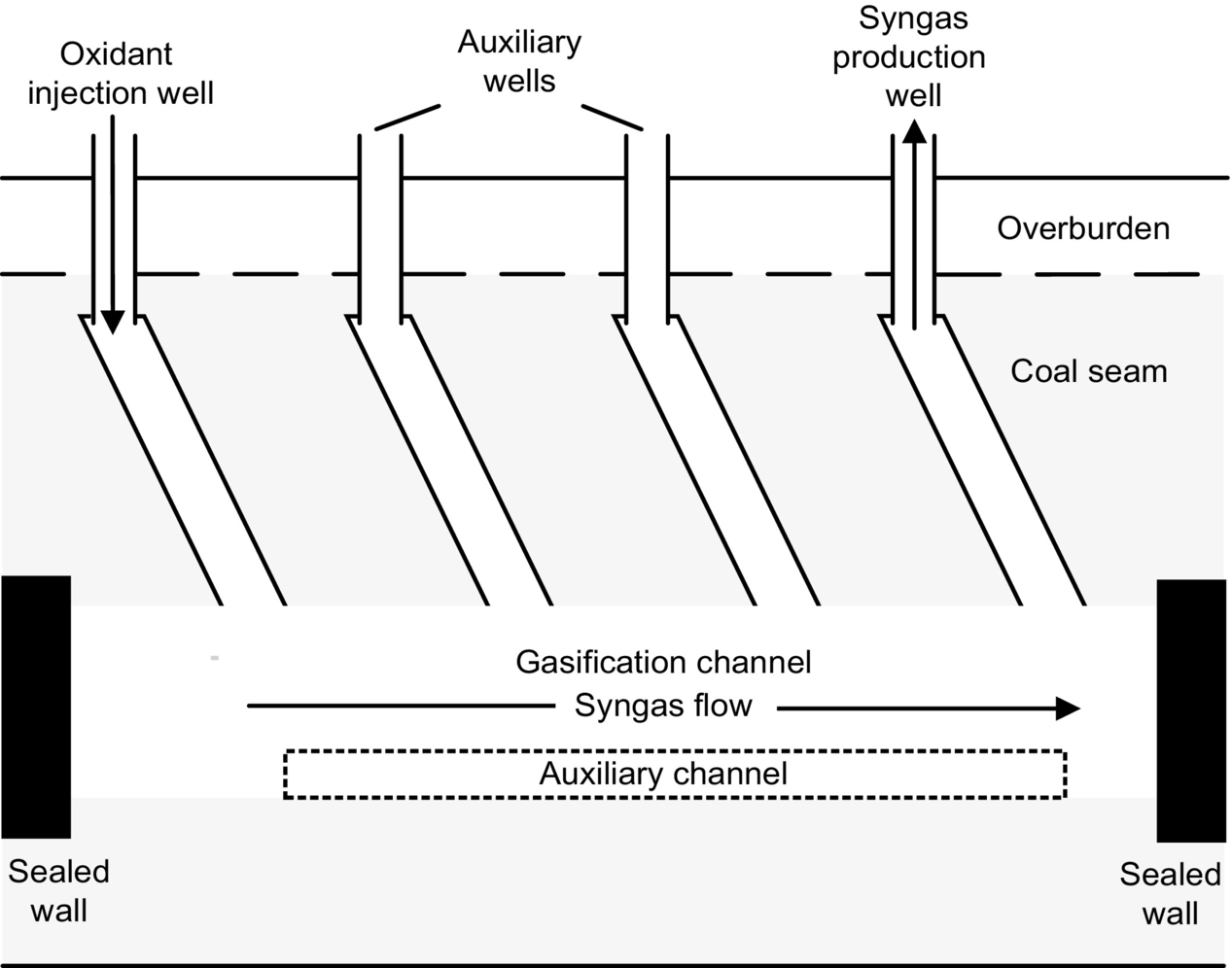

UCG has been approached in numerous ways. The oldest and most basic UCG approach utilizes two drilled wells that act as injection and production wells as illustrated in Fig. 10.1. The basic method involves three main steps. Initially, the injection and production wells are drilled to the coal seam, and a permeable flow path is established between the wells. In situations where the natural permeability of a coal seam is low, it can be increased using techniques including forward combustion linking (FCL), reverse combustion linking (RCL), electrolinking, hydrofracturing, and directional drilling (Blinderman et al., 2008).

Once a flow path between the wells has been created, the second step is ignition. Gasification begins with ignition of the coal and introduction of gasifying agents into the coal seam through the injection well. This triggers an in situ substoichiometric combustion process, producing syngas (Kempka et al., 2011). Coal ignition is initiated through the use of an electric coil or gas firing near the face of the coal seam (Daggupati et al., 2011a). Gasifying agents can be in the form of air, oxygen, steam/air, and steam/oxygen (Perkins and Sahajwalla, 2007). Continuous oxidant flow through the injection well allows for gasification to be sustained (Daggupati et al., 2011a).

Syngas is extracted through the production well and is cleaned prior to use (Van der Riet, 2008). The quality of the product gas is influenced by several parameters—such as the pressure inside the coal seam, coal properties, feed conditions, kinetics, and heat and mass transport within the coal seam—and the product of the UCG process is a multicompound, high-temperature, and high-pressure syngas (Daggupati et al., 2011a). When the syngas reaches the surface, it is cleaned, and undesired by-products are removed from the product stream (Perkins and Sahajwalla, 2008). Removal techniques are similar to those used with surface gasifiers. Once the by-products are removed, they can be disposed of safely or used for other chemical processes (Shafirovich and Varma, 2009). The degree of cleaning required is dependent on the use of the syngas; syngas is cleaned either to meet the specification for input into a gas turbine (for electricity generation) or to be of sufficient purity for use as a chemical feedstock for conversion to synthetic fuels (Walker, 1999).

Over time, the gasification process creates a cavity. Eventually, the coal near to the injection well will be completely converted to syngas, and steps one and two are repeated in order to access new coal and maintain syngas production. Once a coal seam has been exhausted, the last step is to clean and cool the cavity in an attempt to return the environment back to its original state (Imran et al., 2014). The cavity is flushed using steam and water to remove pollutants, preventing them from entering into the local environment.

10.2.2 UCG techniques

Two standard techniques of preparing a coal seam for gasification have been utilized successfully, shaft and shaftless. The method implemented is dependent on parameters such as the natural permeability of the coal seam, geochemistry of the coal, seam thickness, depth, width and inclination, proximity of urban developments, and amount of mining desired (Wiatowski et al., 2012).

10.2.2.1 Shaft UCG methods

Shaft methods use coal mine galleries and shafts to transport gasification reagents and products, which sometimes entail the creation of shafts and the drilling of large-diameter openings through underground labor (Wiatowski et al., 2012). The shaft method was the first technique utilized within UCG systems. Currently, the shaft method is only employed in closed coal mines for reasons of economics and safety (Wiatowski et al., 2012). Examples of common UCG shaft methods include chamber or warehouse method, borehole producer method, stream method, and long and large tunnel gasification method.

Chamber or warehouse method

This method utilizes constructed underground galleries with brick walls separating coal panels. Gasification agents are supplied to a previously ignited coal face on one side of the wall, and the syngas is removed from a gallery on the other side. The chamber method strongly relies on the natural permeability of the coal seam to allow for sufficient oxidant flow through the system. The syngas composition may vary during operation, and the gas production rates are often low. To improve system output, coal seams are often outfitted with explosives for rubblization prior to the reaction zone (Lee et al., 2014).

Borehole producer method

For this method, parallel underground galleries are created within a coal seam with sufficient distance between them. The galleries are connected by drilling boreholes from one gallery to the other (Wiatowski et al., 2012). Remote electric ignition of the coal in each borehole is used to initiate the gasification process. This method is designed to gasify considerably flat-lying seams. Some variations exist where linking of the galleries is accomplished through hydraulic and electric linking (Lee et al., 2014; Wiatowski et al., 2012).

Stream method

This method is designed for sharply inclined coal beds. Parallel pitched galleries following the contour of the coal seam are constructed and are connected at the bottom of the seam by a horizontal gallery also known as a fire drift. To initiate gasification, fire is introduced within the horizontal gallery. The hot coal face moves up the seam slope with oxidant fed through one inclined gallery and syngas leaving through the other. The main advantage of this method is that the ash and roof material drop down fill the void space created during the process, which prevents suffocating the gasification process at the coal front (Lee et al., 2014).

Long and large tunnel gasification method

This method utilizes mined tunnels or constructed roadways to connect the injection well to the production well (Roddy and Younger, 2010). Typical long and large tunnel (LLT) systems consist of a gasification channel, injection and production wells, two auxiliary wells, and tunnels connecting the wells to the gasification channel (Fig. 10.2). The auxiliary wells are arranged between the injection and production wells and are used as malfunction wells for the injection of air and water vapor or to discharge gas that increases gasifier control. LLT also includes an auxiliary tunnel constructed of bricks, which is a supplementary installation for air injection that prevents blockage in the gasification channel. The mined tunnels are isolated by sealing walls to prevent leakage of combustible gases from the gasifier (Liang et al., 1999). The location and height of the oxidant injection points and gas outlet points can be adjusted, allowing for two-dimensional control of oxidant injection and gas production (Yang et al., 2003).

10.2.2.2 Shaftless UCG methods

Recently, most of the focus of UCG research has been on shaftless methods, which employ directional drilling techniques (Hammond, 2000). With shaftless methods, all preparation and operational processes are carried out through a series of boreholes drilled from the surface into a coal seam and do not require underground labor. Preparation of a shaftless reactor consists of the creation of dedicated in-seam boreholes for oxidant injection and product collection using drilling and completion technology that has been adapted from oil and gas production (Wiatowski et al., 2012); the approach generally includes drilling inlet and outlet boreholes into a coal seam, increasing the coal permeability between the inlet and outlet boreholes, igniting the coal seam, introducing an oxidant for gasification, and extracting the product gas from the outlet well (Lee et al., 2014).

Currently, there are two main classifications of shaftless UCG methods, linked vertical well (LVW) and controlled retractable injection point (CRIP).

Linked vertical well method

The LVW method is one of the oldest methods for UCG and is derived from technology developed in the former Soviet Union (Shafirovich and Varma, 2009). Vertical wells are drilled into a coal seam, and internal pathways in the coal are utilized to direct the oxidant and product gas flow from the inlet to the outlet borehole. Internal pathways can be naturally occurring or constructed (Liang et al., 1999). In its simplest form, the LVW method has inlet and outlet borehole locations that are static for the life of the system. During operation, the coal face migrates, and it is found that system control, performance, and syngas quality are affected negatively as the distance from the coal face to the oxidant injection point increases (Roddy and Younger, 2010); this factor greatly reduces the feasibility of simple LVW systems.

A more advanced LVW approach involves a series of dedicated injection boreholes located along the length of a coal seam (Lee et al., 2014). Over the life of a UCG reactor, the coal face, being gasified, travels as localized coal is exhausted (Roddy and Younger, 2010). Having multiple boreholes for injection allows for improved static operating conditions. A more complex variation of the LVW method also exists where multiple inlet and outlet boreholes are drilled into a coal seam, forming inlet and outlet borehole pairs. Parallel inlet and outlet manifolds are connected to the boreholes to provide a path for oxidant and syngas flows, respectively. Coal between each pair of inlet and outlet boreholes forms a zone. When the coal in a zone has been exhausted, new boreholes are drilled in a location of fresh coal, forming new zones (Lee et al., 2014).

Low-rank coals, such as lignites, have considerable natural permeability and can be exploited for UCG without the need for linking technologies. However, high-rank coals, such as anthracites, are far less permeable, making the gas production rate more limited if UCG is employed (Liang et al., 1999). For the use of high-rank coals in UCG, a method of linking must be employed to increase the permeability and fracture the coal seam (Blinderman and Klimenko, 2007). The boreholes in traditional LVW gasifiers are linked by through forward combustion, reverse combustion, fire linkage, electric linkage, hydrofracturing, and directional drilling to create sizable gasification channels (Blinderman et al., 2008; Liang et al., 1999).

Controlled retractable injection point method

Over the span of a coal seam, the geometry may change, resulting in variable UCG operation and system performance (Nourozieh et al., 2010). In the past, this problem was solved by having multiple injection and/or production wells so that static operating conditions could be accomplished through moving the gasifier zones to fresh coal (Shafirovich and Varma, 2009). CRIP offers an alternative approach where the vertical injection well is not moved, but the injection point is moved within the coal seam to fresh coal when necessary (Klimenko, 2009).

The CRIP method relies on a combination of conventional drilling and directional drilling to access the coal seam and physically form a link between the injection and production wells, without the use of linking technologies utilized in LVW methods (Nourozieh et al., 2010). A vertical section of injection well is drilled to a predetermined depth, after which directional drilling is used to expand the hole and drill along the bottom of the coal seam creating a horizontal injection well (Wang et al., 2009). At the end of the injection well, a gasification cavity is initiated in a horizontal section of the coal seam, creating a localized reactor. The CRIP system utilizes a burner attached to retractable coiled tubing that is used to ignite the coal (Klimenko, 2009). The burner burns through the borehole casing to ignite the coal. The ignition point can be moved to any desired location along the horizontal injection well for the creation of a new gasification cavity after a deteriorating reactor has been deserted (Nourozieh et al., 2010). Typically, the injection point is retracted using a gas burner, which burns a section of the liner at a desired location (Klimenko, 2009). In this manner, accurate control of the gasification process can be obtained. This UCG method has gained popularity in Europe and the United States, but the use of the CRIP method for UCG is fairly new and currently has not become commonly employed (Roddy and Younger, 2010).

10.2.3 Chemical processes

UCG is similar to surface gasification where syngas is produced through the same chemical reactions (Ludwik-Pardała and Stańczyk, 2015; Pana, 2009). The main chemical processes occurring during coal gasification are drying, pyrolysis, combustion, and gasification of the solid hydrocarbon (Stańczyk et al., 2012).

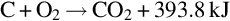

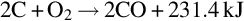

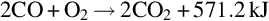

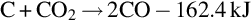

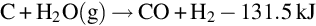

Temperature, pressure, and gas composition vary along the gasification channel. As a result, the chemical reactions that occur in the channel vary with location. Based on the chemical reactions occurring, the gasification channel can be divided into three zones: oxidization, reduction, and dry distillation and pyrolysis (Ludwik-Pardała and Stańczyk, 2015; Yang et al., 2010) as seen in Fig. 10.1. The oxidation zone is located where the gasification agents are introduced to the ignited coal face. In the oxidization zone, multiphase chemical reactions occur between the oxygen in the gasification agents and the carbon in the coal. The highest temperatures in the gasification channel occur in the oxidation zone, due to the degree of exothermic reactions occurring (Lee et al., 2014). The temperature of the coal face in this zone typically ranges from 900 to 1500°C (Bhutto et al., 2013; Perkins and Sahajwalla, 2008). The main chemical reactions, specific to the oxidation zone, include

As the oxygen is consumed, the gas stream enters the reduction zone. The reduction zone begins at the same location of the oxidation zone and is typically 1.5–2 times the length. Temperatures typically range from 600°C to 1000°C. In this zone, water vapor and carbon dioxide are reduced to hydrogen gas and carbon monoxide due to high temperatures (Bhutto et al., 2013; Perkins and Sahajwalla, 2005).

The following endothermic reactions occur in the reduction zone (Lee et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2003):

Coal ash and metallic oxides are formed in the gasifier, which act as catalysts, allowing for methanation to occur in the reduction zone:

Due to the endothermic reactions that occur in the reduction zone, the temperature in the reduction zone decreases until the reduction reactions cannot be sustained.

Once the temperature is reduced, the gas then enters the dry distillation and pyrolysis zone. This zone can extend the entire length of gasification channel, and the temperature in this zone typically ranges from 200°C to 600°C. The main process that occurs in this zone is dewatering of the coal, where water is vaporized, causing the coal to dry and crack. At the beginning of the dry distillation and pyrolysis zone, when temperatures are over 550°C, H2, CO2, and CH4 are still produced. As the flow progresses through the gasification channel, the temperature drops due to heat transfer with the surrounding coal (Yang, 2008). When the temperature is between 350°C and 550°C, high degree of tar and a limited amount of combustible gases are created. Chemical reactions and light polymerization and depolymerization continue to occur as temperatures decrease to approximately 300°C (Bhutto et al., 2013). Within the dry distillation and pyrolysis zone, the coal seam is decomposed into multiple possible volatiles including H2O, CO2, CO, C2H6, CH4, H2, tar, and char (Lee et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2003). As the temperature decreases, some of these volatiles are separated out and become viscous. The UCG process can also have other by-products, including H2S, As, Hg, Pb, and ash depending on the coal quality, oxidant, and operating conditions (Yang et al., 2010; Shu-qin et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2006a). At the exit of the gasification channel, syngas is typically extracted from the production well between 200°C and 400°C with the volatile composition consisting mostly of CO, CO2, H2, and CH4 (Liu et al., 2006b). The composition of syngas at the end of the gasification channel is highly dependent on the gasification agent, air injection method, and coal composition (Prabu and Jayanti, 2012; Stańczyk et al., 2011).

During operation, the three gasification zones move along the coal seam, ensuring continuous reactions throughout the channel (Lee et al., 2014). A distinguishing feature of UCG, compared with surface gasification, is that drying, reduction, pyrolysis, and oxidation can occur simultaneously within the coal seam (Perkins and Sahajwalla, 2005), and the areas where these reactions occur in the gasification channel overlap.

10.2.4 Physical processes

The high temperatures associated with UCG cause the formation of temperature fields in the coal, localized rock mass, and strata. This leads to changes in the physical and mechanical properties of the coal and rock mass. Differences in thermal expansion between coal grains cause the formation of cracks, which can contribute to the overall gasification cavity and increase gas permeability (Yang, 2003).

Yang and Song (2001) found that the coal and rock densities are greatly affected by temperature and pressure and do not remain constant during operation. Small changes in the physical properties of the coal and rock affect the temperature field and the seepage of underground water. Coal and rock are deformed by fluid pressure in pores and cracks. The fluid content in cracks and pores changes the stress and strain forces within the coal, which changes the elastic modulus and compressive strength of the coal and rock (Bhutto et al., 2013).

The entire process is confined to the space of the coal seam and is sealed from the surface by natural geologic formations or man-made barriers; the coal seam and strata serve, to some extent, as a natural groundwater cleaning system. In general, systems have active pressure control, in which the cavity pressure is held in equilibrium or below that of the surrounding strata (Van der Riet, 2008; Shu-qin et al., 2007). The pressure difference induces flow into the reactor space, which inhibits gasification products from leaking away from the cavity (Wiatowski et al., 2012; Yang, 2008).

10.3 UCG modeling

Though UCG is similar to surface gasification, there are many chemical and physical phenomena that occur during UCG including combustion, gasification, fluid flow, and rock mechanics, and these cannot be controlled or easily monitored (Khan et al., 2015; Seifi, 2014). With UCG, the quantifiable parameters are typically limited to coal and seam properties, gas production rate, gas composition, localized temperature, and operating conditions, which vary between sites and systems (Elahi, 2016; Golec and Ilmurzyńska, 2008). The combination of complex phenomenon, limited measurable parameters, and site specificity makes operation and control of UCG systems difficult compared with surface gasifiers. These difficulties motivated the creation of quantitative models to predict the effects of various physical and operating parameters on system operation and performance.

Numerous laboratory coal block experiments have been conducted including those by Hamanaka et al. (2017), Bhaskaran et al. (2015), Stańczyk et al. (2011), Prabu and Jayanti (2011), Daggupati et al. (2010), Yang (2003), Yeary and Riggs (1987), and Poon (1985). Experiments investigated the effect's oxidant type, injection rate, temperature and pressure, steam-to-oxygen ratio, combustion time and distance between wells on the product gas composition, extraction rate, and temperature. Temperature distribution throughout the coal and cavity formation have also been investigated. Although laboratory-scale experiments can provide insight into the processes involved with UCG, applying the data and creating accurate UCG models have limited scope since all phenomenon associated with UCG and the interactions between them may not be accurately represented (Upadhye et al., 2006). There are two main types of UCG models, process and global. Process models involve studying specific UCG processes or phenomena, and global models consider the entire UCG process. Early UCG development was limited, and research involved isolated processes including heat transfer, mass transfer and combustion rate, and development of process models (Gunn and Krantz, 1987). As UCG research developed, there has been increased interest in the creation of a global model to simulate UCG.

A global model that encompasses all the processes and phenomena associated with UCG would be composed of submodels that represent injection/production linkage, UCG reactor, groundwater hydrology, ground subsidence and surface facilities, and gas processing. Using these submodels simultaneously would hypothetically provide a complete description of the UCG process but would require significant effort. As such, the submodels have focused on analysis of the characteristics individually using several simplifying assumptions (Khan et al., 2015). Overall, an effective global model would

1. analyze transient temperature profiles within the coal seam;

2. calculate the rate of gas and coal consumption;

3. analyze the influence of coal shrinkage or swelling on UCG operation;

4. determine the pressure and velocity of the gases produced in a coal seam of known porosity and permeability;

5. predict the advancing shape of the combustion front;

6. simulate the cavity growth with time;

7. analyze the effect of reactor pressure, oxidant temperature, injection rate, feed mixture ratio and well spacing on production rate, gas composition, heating value, and cavity dimensions;

8. predict the influence of coal seam dimensions and ash and moisture content on production rate, gas composition, heating value, and cavity dimensions.

There are various approaches to modeling UCG including packed-bed models, coal block models, and channel models (Khan et al., 2015; Seifi, 2014), and numerous quantitative models have been created utilizing these methods. Early models were one-dimensional, but with the improvement of computer hardware and software, two dimension and three dimension have also been created. The following sections describe the various modeling methods and approaches.

10.3.1 Packed bed models

Packed-bed models are the earliest UCG models created. Packed-bed models define the UCG reactor as packed-bed reactor and are primarily applicable to laboratory-scale projects. Packed-bed models simulate gasification in a highly permeable porous medium with a stationary coal bed that is consumed over time (Seifi, 2014). Early models considered the creation of a permeable region between two boreholes through such processes as reverse combustion and hydrofracturing (Uppal et al., 2014).

One-dimensional models were first developed by Winslow (1977) and Thorsness et al. (1978) through the use of a finite difference approach. They achieved good predictions of gas production, gas composition, and coal consumption from laboratory experiments on crushed coal (Seifi, 2014). Later, Abdel-Hadi and Hsu (1987) and Thorsness and Kang (1986) developed packed-bed models in two-dimensional and compared their results with Thorsness et al. (1978). Recent one-dimensional packed-bed models have been developed by Uppal et al. (2014) and Khadse et al. (2006).

Packed-bed models can accurately represent coal gasification at the laboratory scale; however, they are not appropriate for field-scale UCG processes. The majority of pack-bed models are one-dimensional. Modeling field-scale gasifiers would require three-dimensional analysis, and due to increased reactor size, the computation time would grow significantly (Khan et al., 2015). In addition, packed-bed models do not incorporate geomechanical considerations, including thermomechanical failure, which may have significant effect on UCG operation and cavity growth. Thorsness et al. (1978) made some predictions for field-scale UCG, but a comparison between their results and field-scale data was not performed.

10.3.2 Coal block models

Some models attempt to describe a UCG coal seam as a coal block. In coal block models, it is assumed that gasification begins from one end of a semi-infinite block of coal with lower permeability than in the packed-bed model. Unlike other models, coal block models consider different layers, and for each layer, separate mass and energy balances are typically analyzed resulting in governing equations for mass and energy balances of split boundary types. These models describe the process by movement of defined regions in a coal slab perpendicular to the flow of the injected oxidant gas. These regions usually include the gas film, ash layer, char region, dried coal, and virgin coal. The presence of various regions is due to a low heating rate of the UCG. At a very high heating rate, there is a possibility of drying and combustion fronts existing simultaneously (Tsang, 1980). Mass flux is considered to be diffusion dominant.

Tsang (1980) was the first to use this approached considering the observation of the development of drying, pyrolysis, and gas-char reactions zones around the most permeable path in the coal seam. Tsang (1980) based the approach on the profiles of temperature and saturation and the direction of heat and mass transfer exhibited from the pyrolysis experiments performed by Westmoreland and Forrester (1977). Coal block models that have been created recently include Elahi (2016); Khan et al. (2015); Seifi (2014); Perkins et al. (2003); Perkins and Sahajwalla (2005, 2006); Beath et al. (2000); Van Batenburg et al. (1994).

The main feature of the coal block model is the ability to track the drying and combustion front movement. This model can effectively determine the drying and devolatilization behavior of large coal particles; however, this model approach has not been validated using UCG field trial data (Khan et al., 2015). Numerous coal block models have been created under atmospheric conditions. However, the pressure is significantly higher than atmospheric in UCG field trials (Seifi, 2014). Also, by assuming a semi-infinite coal block, models are typically limited to use with thick coal seams. The majority of the coal block models only include one-dimensional analysis, so information on cavity shape cannot be accurately determined using them (Seifi, 2014; Khan et al., 2015).

10.3.3 Channel models

Channel models overcome the limitation associated with determining UCG cavity shape and size. In channel models, a coal seam is assumed to have a cylindrical geometry with a cylindrical or rectangular channel in the middle of the seam. The channel model assumes that coal is gasified at the perimeter of an expanding permeable channel, and all heterogeneous reactions take place on the channel wall (Seifi, 2014). When determining cavity shape and size, the channel model is preferred (Khan et al., 2015). The channel model is found to better calculate sweep efficiency (Seifi, 2014).

With channel models, the UCG process is characterized by an expanding channel where two separate zones of rubble/char and open channel exist. The approach was developed through the observation that an open-channel structures have developed in different UCG field tests (Van Batenburg et al., 1994; Kuyper and Bruining, 1996). Recent channel models include those developed by Plumb and Klimenko (2010), Luo et al. (2009), Perkins and Sahajwalla (2007), Pirlot et al. (1998), and Kuyper et al. (1994).

For the majority of channel models, there is a high degree of concentration on heat transfer related to UCG. The consideration of natural convection is found to be one of the main phenomena in channel model development. Some models successfully incorporate water influx (Elahi, 2016). Most channel models neglect drying and pyrolysis, which are considered significant in other UCG model approaches. Few channel models include thermomechanical failure. Even without these considerations, many of the channel models have been validated with data from field trials. Most existing channel models are in two dimensions; however, a few three-dimensional models exist that allow cavity shape and size to be visibly obtained (Seifi, 2014).

10.4 UCG with CO2 capture and storage

Mitigating global climate change is a substantial problem currently. Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with fossil-fuel combustion are a significant contributor to global warming. The energy sector is one of the main sources of CO2 emissions due the predominant use of fossil fuels (International Energy Agency, 2014). A technology that can help decrease emissions is carbon capture and storage. CO2 is captured, transported to suitable storage location, and typically injected into underground geologic formations (Schiffrin, 2015; Selma et al., 2014). Coal is commonly used throughout the world for energy production; however, coal has the highest CO2 emissions, per unit energy produced, of the fossil fuels when combusted (Khadse et al., 2007; Nag and Parikh, 2000). To maintain and expand the use of coal, implementation of CCS technologies is becoming vital (Selosse and Ricci, 2017). According to the International Energy Agency, CCS could account for up to 19% of the global emission reductions by 2050 (International Energy Agency, 2010).

CO2 capture can be performed in three main fashions: precombustion, post combustion, and oxy-firing (Göttlicher and Pruschek, 1997). A broad range of technology options are available for capturing CO2 including physical absorption, chemical absorption, membrane separation, and cryogenic separation (Ho et al., 2006; Göttlicher and Pruschek, 1997). In UCG, the syngas compositions, temperatures, and pressures of production streams at the exit of a production well are comparable with those of surface gasifiers, which allow similar methods of CO2 capture. Due to the similarities to surface gasifiers, it is believed that the CO2 contained in the UCG syngas could be processed and separated using physical sorbents, within a precombustion arrangement, which has costs comparable with capture technologies commonly utilized in integrated gasification combined cycles (Selosse and Ricci, 2017; Roddy and Younger, 2010; Burton et al., 2006). Postcombustion methods are also applicable and would be directly comparable in terms of cost and performance with typical postcombustion systems utilized in power plants. Oxy-firing options are possible for UCG as well, and within a power-generating scenario, an air separation unit can generate O2 streams for injection into the UCG and for use in an oxy-fired plant utilizing the syngas (Burton et al., 2006).

The spatial coincidence of geologic carbon storage (GCS) options with UCG opportunities suggests that designers could collocate and combine UCG and GCS systems with high potential for effective CO2 storage (Roddy and Gonzalez, 2010). In general, these storage options would be the same for conventional carbon sequestration operations, including saline formations and mature oil and gas fields (Friedmann et al., 2009). For UCG systems with CCS, there could exists commonality in site characterization and monitoring for both UCG and CCS projects, where work performed during the design and implementation of one project could be used within the other. Coordinating UCG and CCS designs would improve economics for both projects.

If UCG and CCS are coupled, there is an attractive carbon management scheme that could be implemented, where the produced CO2 emissions are sequestered back into a coal seam void that has been recently created through UCG activities using existing injection and production wells (Lee et al., 2014; Khadse et al., 2007). When voids are created, they typically collapse, similar to voids produced during longwall coal mining, leaving zones of artificial breccias with high permeability. Suitable containment zones prevent vertical flow of CO2 to the surface, where storage locations are isolated from the surface by low-permeability strata (known as seals or caprocks, often shales or evaporites) (Roddy and Younger, 2010; Orr, 2009). For a spent UCG system to accommodate CO2 storage, the void must be at depths below approximately 800–1000 m (Budzianowski, 2012; Friedmann et al., 2009; Orr, 2009). These depths are required so that supercritical pressures and temperatures exist allowing the CO2 density to be high enough (approximately 500–700 kg/m3) to limit the storage volume required (Orr, 2009).

The UCG-CCS approach, if successfully implemented, could offer an integrated energy recovery and CO2 storage system, which exploits a new sequestration resource created during UCG operation. A significant challenge with CCS is the large energy requirement associated with CO2 capture and compression (Gibbins and Chalmers, 2008; Steinberg, 1999). The pressure after compression is generally high enough to allow for a reduction in pressure during transport while allowing the fluid to be in a liquid state (Ghose and Paul, 2007). If CO2 storage is accommodated in spent UCG reactors, CO2 transport and compression requirements decline. CO2 transport typically accounts for 5%–15% of conventional CCS costs for systems with long transport distances. Costs could be significantly lowered through the reduced piping and shipping requirements associated with a self-contained UCG-CCS project (Roddy and Gonzalez, 2010). A large portion of the cost for a CCS project is allotted for CO2 storage, typically 10%–30%, which is mostly used for geologic and geophysical studies and drilling injection wells (Roddy and Gonzalez, 2010; Gibbins and Chalmers, 2008). These tasks are commonly completed during UCG construction and would not necessarily need to be repeated for the implementation of CCS, thus reducing system cost relative to conventional storage methods (Roddy and Gonzalez, 2010).

An important CCS challenge relates to the significant energy requirements associated with removing CO2 from a gas stream and compressing it to a state suitable for transport and storage. Similar to surface gasifier units, the implementation of precombustion CO2 removal can be adopted, using current technology. For conventional fossil-fuel power-generating plants, the energy requirements are typically in the range of 10%–40% of the total net plant output, which results in a reduction in plant efficiency (Romano et al., 2010; Thambimuthu et al., 2005; Herzog and Drake, 1998).

As of 2009, it remains unclear if CCS using UCG-produced voids is viable (Friedmann et al., 2009). Until recently, this alternative has received little attention, and there remains substantial scientific uncertainty associated with the technological challenges and environmental risks of storing CO2 in this manner (Friedmann et al., 2009; Khadse et al., 2007). For full-scale commercialization, extensive research and development is needed to alleviate the uncertainties. Currently, CO2 sequestration is under development internationally by such organizations as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum (Khadse et al., 2007). Recent research studies into CCS and UCG include those by Yang et al. (2016), Kasani and Chalaturnyk (2017), McInnis et al. (2016), Sheng et al. (2016), Prabu and Geeta (2015), Schiffrin (2015), and Verma and Kumar (2015).

10.5 UCG with CCS and auxiliary power plant: case study

One advantage of UCG is the potential for CO2 emission reductions through the use of CCS technologies. Precombustion CO2 processing systems used in industry commonly utilize physical absorption-based plants to capture CO2 from the syngas stream; though less common, chemical absorption, with amine-based solvents, is also used for precombustion carbon capture (Padurean et al., 2012). Amine-based systems are the oldest and most well-understood CO2 capture technology on the market but are mostly used in postcombustion applications, due to their high efficiency under low-pressure conditions (Letcher, 2008). Even though the efficiency is reduced when amine systems are used in high-pressure applications, Padurean et al. (2012) found that these systems have higher carbon capture rates than physical absorption methods, which would be beneficial within UCG systems due to their large scale and potential for high syngas production rates. The benefit of using amine chemical absorption within UCG systems is increased when the coal, in underground gasifier, is at shallow depths allowing for lowered operating pressures.

Amine systems require a significant amount of thermal energy to separate CO2 from the amine fluid, in a splitter reboiler, prior to compression (Harkin et al., 2010). The thermal requirements for current and developing amine-based technology range from 1.2 to 4.8 GJ/t CO2 (1.20–4.80 MJ/kg CO2), which is supplied by saturated steam at pressures of 310 kPa or higher (Harkin et al., 2010; Romeo et al., 2008; Kvamsdal et al., 2007). In general precombustion systems currently employed in industrial plants can capture 85%–95% of the total CO2 in a flow (Romano et al., 2010; IPCC, 2005; Thambimuthu et al., 2005). CO2 compression requires mechanical work to increase its pressure to levels suitable for transport, which typically range from 324 to 432 kJ/kg CO2 (Aspelund and Jordal, 2007).

The UCG process produces a high-temperature, high-pressure syngas, which can contain many chemical components depending on the coal quality and operating conditions (Liu et al., 2006b). Before the syngas can be used in power generation, it requires processing to remove unwanted gasification products, which requires the syngas to be cooled to a suitable temperature, coinciding with the processing technology utilized. Conventional gas processing temperatures range from 150°C to 600°C (Hamelinck and Faaij, 2002; McMullan et al., 1997).

This case study examines the feasibility of implementing an auxiliary power plant, utilizing the thermal energy removed during the cooling of the syngas, to provide the energy required for CO2 capture, through amine-based chemical absorption and compression within a UCG system. The amount of power produced by the auxiliary plant is compared with the energy requirements of a UCG system with CO2 processing, including air injection, CO2 capture and compression, and pump work within the auxiliary plant. Parametric studies are performed to investigate the effects on system performance of air injection flow rate, power requirements for CO2 capture and compression, and syngas cooling.

10.5.1 System description

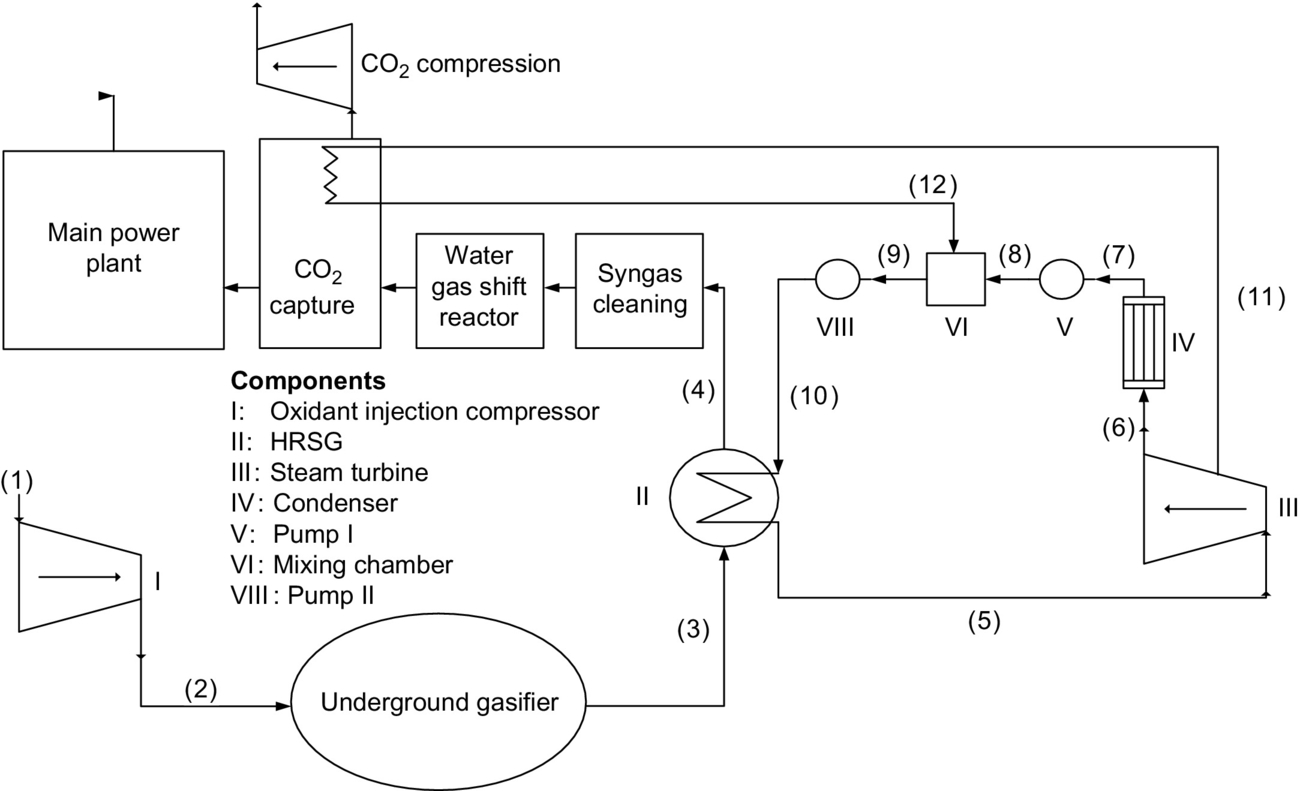

The system considered here for UCG system with CO2 capture and compression is based on the Newman Spinney P5 field test and illustrated in Fig. 10.3. The Newman Spinney P5 field test is theoretically combined with precombustion CO2 capture and compression and auxiliary Rankine cycle, as seen in Fig. 10.3. Air is compressed and fed to an underground reactor, where syngas is produced through gasification and conveyed to the surface via a production well. The syngas is cooled in a single-pressure heat recovery steam generator (HRSG). Cooled syngas flows from the HRSG to the gas processing, including water-gas shift and CO2 capture sections. The cleaned syngas enters a plant to be combusted and used in electricity production. CO created within the underground gasifier is converted to CO2 within a water-gas shift reactor. The CO2 from the gasifier and water-gas shift reactor is captured using an amine solvent-based capture process, which requires thermal energy for separating the CO2 from the working fluid in a splitter reboiler. CO2 enters a compression process to prepare the CO2 stream for pipeline transport.

Steam produced in the HRSG is utilized within a Rankine cycle to drive a turbine arrangement producing work. A portion of the steam is extracted from the turbine, as saturated steam at an intermediate pressure, to supply thermal energy to the splitter reboiler. The remaining steam exits the turbine and is condensed. The pressure of the condensed steam is raised to the extracted steam pressure. The condensed steam and extracted steam streams are mixed in a mixing chamber, and the fluid pressure is raised to the HRSG pressure by a second pump prior to entering the HRSG.

The Newman Spinney P5 field test is a shallow depth UCG trial that was conducted at Newman Spinney, Derbyshire, during 1958 and 1959. The Newman Spinney P5 field test utilized an open-channel gasifier setup that consisted of four injection boreholes feeding air at a rate of 1.0–3.0 kg/s per borehole and at injection pressures of 120–190 kPa (Perkins et al., 2003). Typical injection conditions include a flow rate of 2.5 kg/s per borehole at 150 kPa, which are utilized within the study. The generating plant originally connected to the Newman Spinney P5 field test had an output of 1–2 MW and a steady-state value of 1.75 MW (Gibb, 1964).

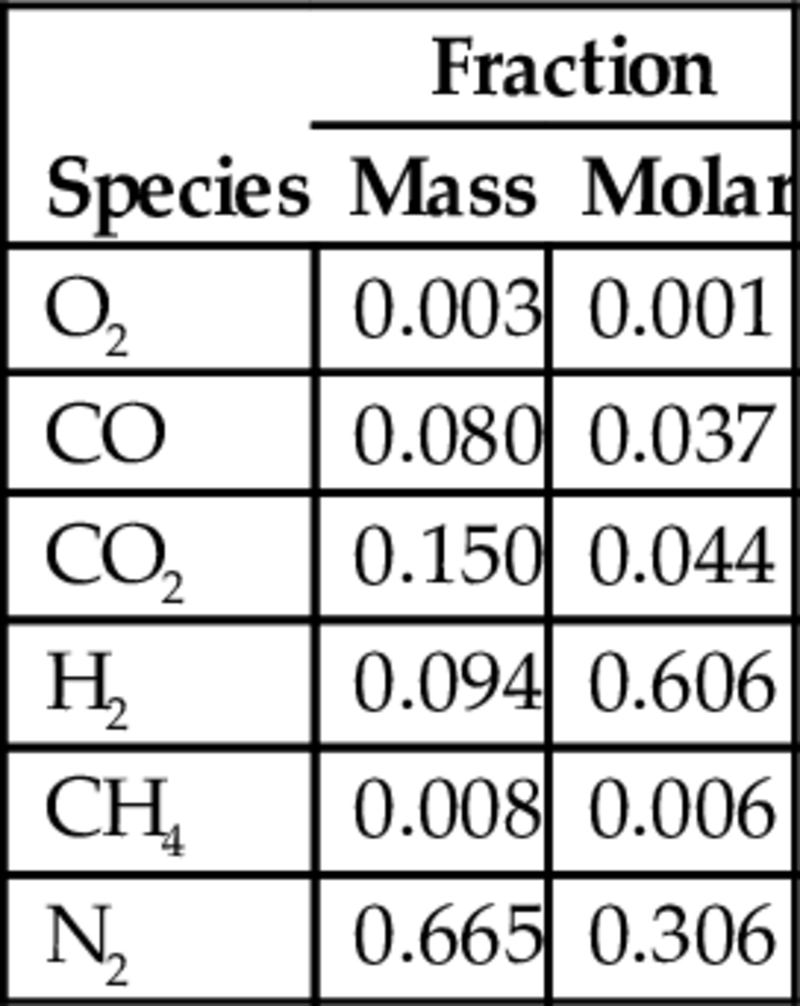

The syngas composition leaving the gasifier is illustrated in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1

Composition of syngas based on dry-gas quantities, at Newman Spinney UCG test plant

| Species | Fraction | |

| Mass | Molar | |

| O2 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| CO | 0.080 | 0.037 |

| CO2 | 0.150 | 0.044 |

| H2 | 0.094 | 0.606 |

| CH4 | 0.008 | 0.006 |

| N2 | 0.665 | 0.306 |

Perkins, G., Saghafi, A., Sahajwalla, V., 2003. Numerical Modeling of Underground Coal Gasification and Its Application to Australian Coal Seam Conditions. Australia: University of New South Wales; Gibb, A., 1964. Underground Gasification of Coal. London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons.

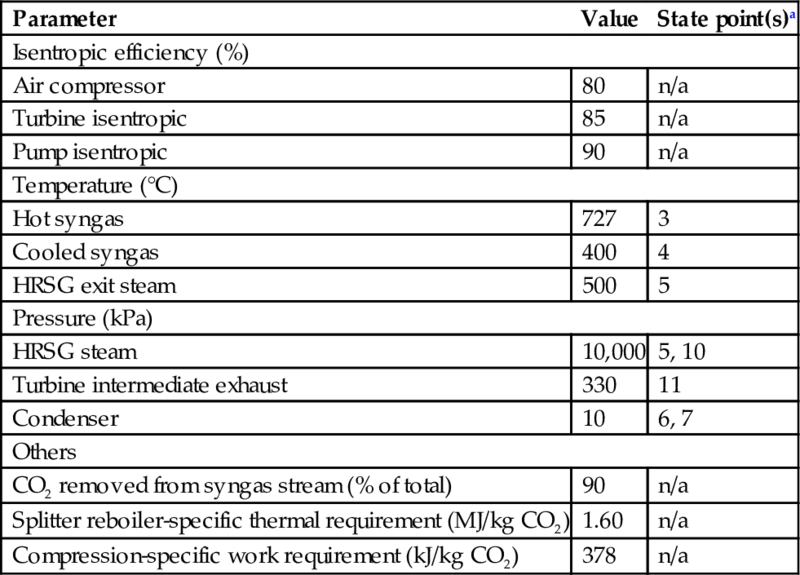

10.5.2 Data and assumptions

For the base system, a temperature of 400°C is assumed for the syngas after cooling, which is approaching the upper temperature limit that is appropriate for syngas cleaning technologies (Hamelinck and Faaij, 2002; McMullan et al., 1997). Limited thermal energy is available for transfer across the HRSG under this condition, which helps to demonstrate the practicality of the illustrated system. Selected system parameters used in the case study are shown in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2

System parameters utilized in analysis

| Parameter | Value | State point(s)a |

| Isentropic efficiency (%) | ||

| Air compressor | 80 | n/a |

| Turbine isentropic | 85 | n/a |

| Pump isentropic | 90 | n/a |

| Temperature (°C) | ||

| Hot syngas | 727 | 3 |

| Cooled syngas | 400 | 4 |

| HRSG exit steam | 500 | 5 |

| Pressure (kPa) | ||

| HRSG steam | 10,000 | 5, 10 |

| Turbine intermediate exhaust | 330 | 11 |

| Condenser | 10 | 6, 7 |

| Others | ||

| CO2 removed from syngas stream (% of total) | 90 | n/a |

| Splitter reboiler-specific thermal requirement (MJ/kg CO2) | 1.60 | n/a |

| Compression-specific work requirement (kJ/kg CO2) | 378 | n/a |

The following general assumptions are made in the analysis:

• The system is at steady state.

• Heat transfer from process components to the surroundings is negligible.

• Pressure drops are negligible within the gasifier, HRSG, condenser, and pipe sections.

• All carbon monoxide contained within the syngas stream is converted to carbon dioxide in the water-gas shift reactor.

• The steam/oxidant ratio within the gasifier remains constant.

• The gasifier product gas composition remains constant (Daggupati et al., 2011b).

10.5.3 Analysis

In this and following sections, the state points coincide with states shown in Fig. 10.3.

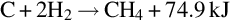

The air compressor work rate  is determined as follows:

is determined as follows:

where  is the mass flow rate of air entering the compressor and h1 and h2 are the specific enthalpies at the inlet and exit of the compressor, respectively.

is the mass flow rate of air entering the compressor and h1 and h2 are the specific enthalpies at the inlet and exit of the compressor, respectively.

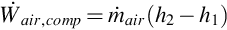

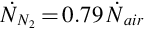

The syngas composition of a known UCG system is utilized, which allows the mass flow rate of the syngas to be found using the air injection rate, under the assumption that nitrogen within the product gas is introduced entirely through air injection. Using the composition of atmospheric air, the air and nitrogen molar injection rates to the reactor are calculated as follows:

where  is the molar flow rate of air injected,

is the molar flow rate of air injected,  is the mass flow rate of air injected, Mair is the molar mass of air, and

is the mass flow rate of air injected, Mair is the molar mass of air, and  is the molar flow rate of nitrogen gas injected.

is the molar flow rate of nitrogen gas injected.

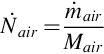

Assuming the nitrogen does not react within the gasifier, the flow rate of nitrogen at the inlet of the reactor is the same as at the exit. The mass flow rate of nitrogen  is

is

where  is the molar mass of nitrogen.

is the molar mass of nitrogen.

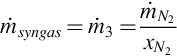

The syngas mass flow rate  is estimated using the mass fraction and flow rate of nitrogen in the syngas:

is estimated using the mass fraction and flow rate of nitrogen in the syngas:

where  is the mass fraction of nitrogen.

is the mass fraction of nitrogen.

The specific enthalpy of a mixture of gases is expressed as the sum of the specific enthalpies of each component and their mass fractions. The specific enthalpy at the gasifier exit is evaluated as

where h3 is the total specific enthalpy at state 3, xi is the mass fraction of species i, and hi,3 is the specific enthalpy of species i at state 3. The specific enthalpy at state 4 is found similarly.

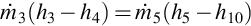

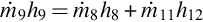

The temperature of the water entering the HRSG is set high enough to prevent low-temperature acid formation on the gas side of the HRSG. Steam temperature and pressure at the exit of the HRSG are set to allow for steam formation rates that facilitate power production from the steam turbine while allowing the flow rate and temperature of the steam leaving the turbine, at the intermediate pressure, to be suitable for use in the splitter reboiler. The steam generation rate is calculated using an energy balance:

where  and

and  are the syngas and steam mass flow rates, respectively. Also, h3 and h4 are the specific enthalpies of the syngas across the HRSG, while h10 and h5 are the specific enthalpies of steam at the inlet and exit of the HRSG, respectively.

are the syngas and steam mass flow rates, respectively. Also, h3 and h4 are the specific enthalpies of the syngas across the HRSG, while h10 and h5 are the specific enthalpies of steam at the inlet and exit of the HRSG, respectively.

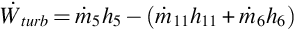

The work rate produced by the turbine  is calculated via an energy balance:

is calculated via an energy balance:

The system has two pumps. Pump work rate is calculated for the pressure difference across the pump and specific volume of the fluid at the pump inlet. Specific enthalpy values at the pump outlets are estimated using specific pump work.

The enthalpy at state 9 is found with an energy balance for the mixing chamber:

where  is the mass flow rate of water leaving the mixing chamber, h9 is the specific enthalpy at the mixing chamber outlet, and h12 is the specific enthalpy of condensed steam leaving the splitter reboiler.

is the mass flow rate of water leaving the mixing chamber, h9 is the specific enthalpy at the mixing chamber outlet, and h12 is the specific enthalpy of condensed steam leaving the splitter reboiler.

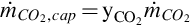

The thermal energy rate required for capturing the CO2 from the syngas stream is estimated using typical thermal requirements for amine absorption:

where  is the thermal energy consumption rate, qcap is the specific thermal energy consumed, and

is the thermal energy consumption rate, qcap is the specific thermal energy consumed, and  is the mass flow rate of CO2 removed from the syngas stream.

is the mass flow rate of CO2 removed from the syngas stream.

The water-gas shift reactor converts CO within the syngas stream into CO2 prior to the carbon capture process. The chemical reaction for the water-gas shift reaction is

It is assumed that 100% of the CO in the syngas stream is converted to CO2.

The mass flow rate of CO2 captured is a percentage of the total CO2 in the syngas stream:

where  is the percentage of CO2 extracted from the syngas steam and

is the percentage of CO2 extracted from the syngas steam and  is the mass flow rate of CO2 in the syngas stream after the water-gas shift reactor.

is the mass flow rate of CO2 in the syngas stream after the water-gas shift reactor.

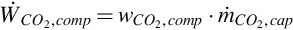

The compression work input rate  is determined using

is determined using

where  is the specific work per kg CO2 compressed.

is the specific work per kg CO2 compressed.

The total work input rate is the sum of work rate inputs for the system. That is,

where  and

and  are the rate of power consumption of pumps one and two, respectively.

are the rate of power consumption of pumps one and two, respectively.

The net work output of the entire UCG system is determined as

To quantify the degree to which the auxiliary plant can supply the work consumed within the system, a parameter called coverage ratio (CR) is introduced. Coverage ratio compares the turbine work output rate to the work consumption rate of the system:

CR < 1 implies the output of the auxiliary plant does not meet the requirements, CR = 1 implies the auxiliary plant meets the requirements exactly, and CR > 1 implies the auxiliary plant output exceeds the requirements.

The energy efficiency of the auxiliary plant, including the reboiler thermal requirements, is defined as

10.5.4 Results and discussion

Using the original assumptions and operating conditions, it was found that the mass flow rate of carbon dioxide captured after the water-gas shift reaction is 13.6 kg/s. The work rate requirements for air compression, feedwater pumping, and CO2 compression are 454 kW, 176 kW, and 5.13 MW, respectively, with a total work requirement of 5.76 MW. The thermal energy rate requirement of the CO2 capture process is 21.7 kW. The work output rate of the auxiliary plant is 12.1 MW, and the net power output of the system is 6.38 MW, which renders a coverage ratio of 2.11. The thermal load of the stripper reboiler in the CO2 capture process is also fulfilled through the extraction of steam at an intermediate pressure within the steam turbine. The auxiliary plant efficiency is 77%.

Overall, the implementation of a Rankine cycle with steam extraction, which provides syngas cooling, within a UCG system appears to be feasible and provides a reasonable net power output. The introduction of this system arrangement could possibly allow for elimination of energy penalties associated with CO2 capture and compression that would otherwise be incurred by the original power production plant. Inclusion of an auxiliary Rankine cycle also allows an increase in the net output of UCG systems; this would be especially beneficial if the syngas produced by the UCG system has a low heating value, resulting in low power plant outputs. The combination of a Rankine cycle and UCG could improve the economic feasibility of UCG use and environmental impacts, while increasing recoverable coal reserves.

10.5.4.1 Effect of air injection flow rate on system performance

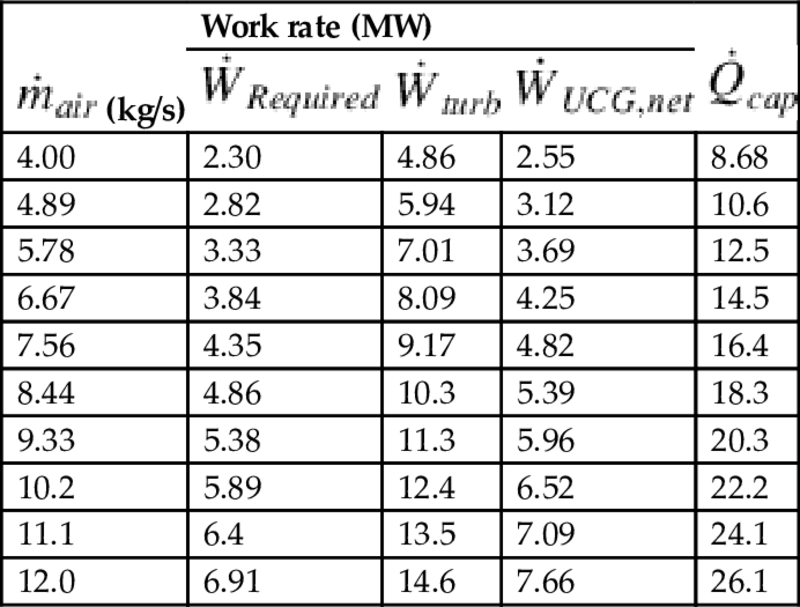

The effect of changing the air injection flow rate on system performance is investigated for air flow rates of 1–3 kg/s per borehole (4–12 kg/s total). It is assumed that the steam/oxidant ratio within the gasifier and all other operating conditions remain constant, allowing for constant syngas composition. The effect of varying air injection flow rate is presented in Table 10.3.

Table 10.3

Effect of air injection rate on selected plant parametersa

(kg/s) (kg/s) | Work rate (MW) |  | ||

|  |  | ||

| 4.00 | 2.30 | 4.86 | 2.55 | 8.68 |

| 4.89 | 2.82 | 5.94 | 3.12 | 10.6 |

| 5.78 | 3.33 | 7.01 | 3.69 | 12.5 |

| 6.67 | 3.84 | 8.09 | 4.25 | 14.5 |

| 7.56 | 4.35 | 9.17 | 4.82 | 16.4 |

| 8.44 | 4.86 | 10.3 | 5.39 | 18.3 |

| 9.33 | 5.38 | 11.3 | 5.96 | 20.3 |

| 10.2 | 5.89 | 12.4 | 6.52 | 22.2 |

| 11.1 | 6.4 | 13.5 | 7.09 | 24.1 |

| 12.0 | 6.91 | 14.6 | 7.66 | 26.1 |

a Coverage ratio is 2.11 for all air flow rates.

As the injection rate increases, the total energy requirements of air compression, CO2 capture, CO2 compression, and feedwater pumping increase linearly, which allows for a constant coverage ratio. This indicates that the air injection rate has a direct relationship with the plant power production and the work rate required by the consuming processes. The change in auxiliary plant output is attributed to the varying amount of energy available for transfer across the HRSG. The increase in work and thermal requirements are caused mostly by increased CO2 flow rates. Although larger injection flow rates do not affect the work coverage ratio, the net work output of the system is found to increase, which implies that for elevated power outputs, increased injection rates are favorable. In contrast, higher injection rates imply that system components have to be larger to accommodate the various loads, which affects the economic feasibility.

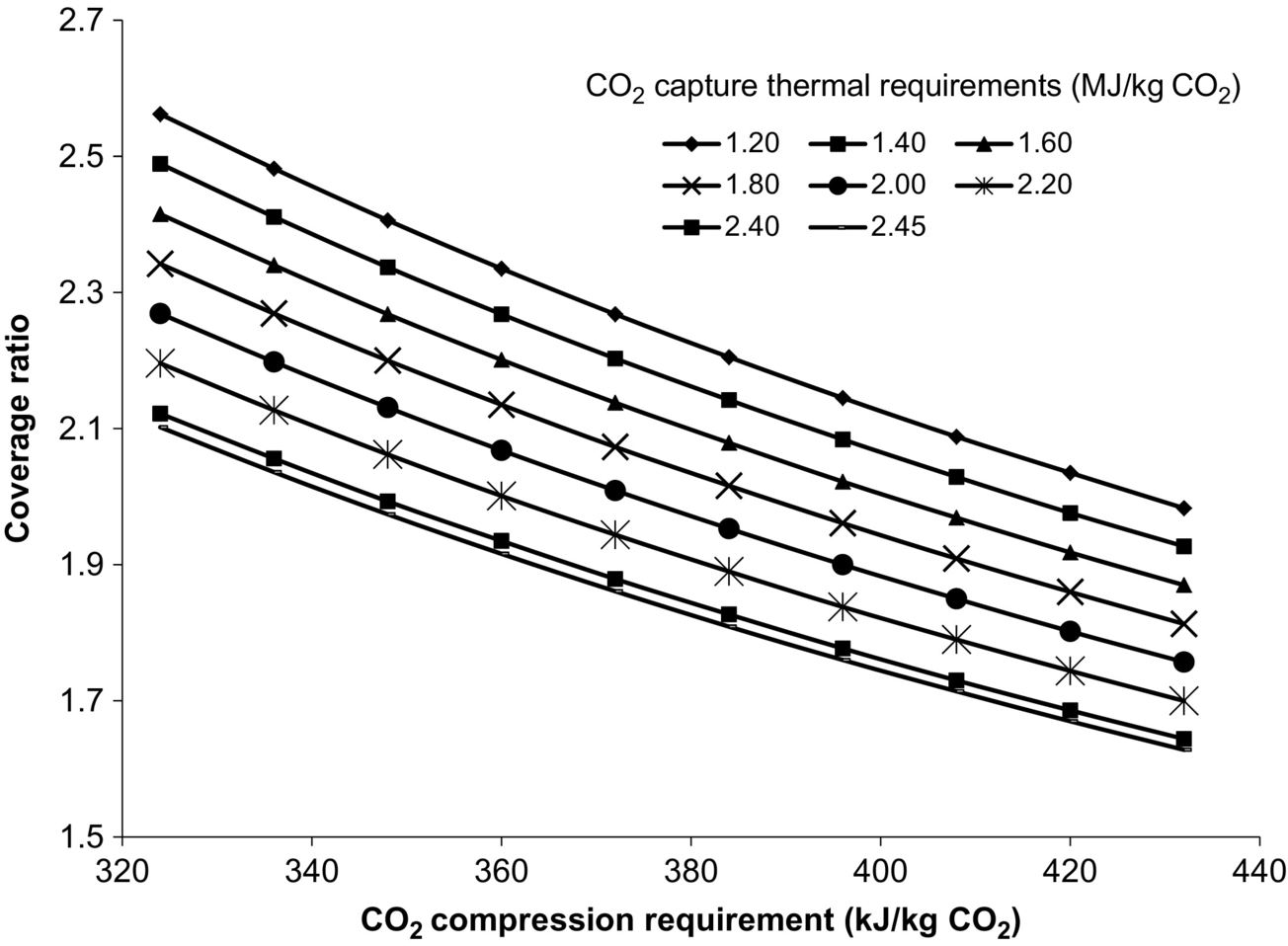

10.5.4.2 Effect of varying power requirement for CO2 capture and compression on system performance

The effect of CO2 capture and compression energy requirements on the coverage ratio are illustrated in Fig. 10.4. The thermal requirements of the splitter boiler are much higher than the work requirements of the CO2 compression process; therefore, the variation in the coverage ratio is more significant over the range of applicable CO2 capture requirements. As thermal requirements of the amine solvent capture process increase, the amount of steam available for use in the turbine beyond the extraction point decreases. This results in a reduced turbine output and associated CR. It is found that the Rankine cycle arrangement, with the given operating conditions, cannot support the entire thermal load of the capture process when the thermal requirement approaches 2.46 MJ/kg CO2. The conditions set for the extracted steam require the flow rate to be higher than that produced by the HRSG. Possible methods of increasing the maximum thermal load the auxiliary system can encounter include increasing the intermediate pressure at which steam is extracted from the turbine and reducing the steam pressure within the HRSG. The effect of using the above options is a reduction in turbine output and CR. As an alternative to reducing turbine output, extracted steam from the Rankine cycle could be used to supply only a portion of the thermal requirements through reducing the flow rate of the extracted steam.

The effect of compression requirements on system performance is not as significant as the thermal requirements of CO2 capture, because the range of typical compression requirements is considerably less than that of CO2 capture. The trends resulting from varying the compressor requirements are identical, which suggests that the compression process has an effect on the coverage ratio independent of the thermal requirements within the capturing process. Compared with the base system, the arrangement with the greatest energy requirements reduces the CR and net work output by 26% and 44%, respectively. Utilizing the lowest power requirements can increase CR and net work output by 19% and 20%, respectively. Reducing the energy requirements for the capture and compression processes is preferred in order to maximize the turbine output of the auxiliary plant and the net work output of the system. Exploiting reduced energy requirements is technologically possible but could require increased process complexity and cost.

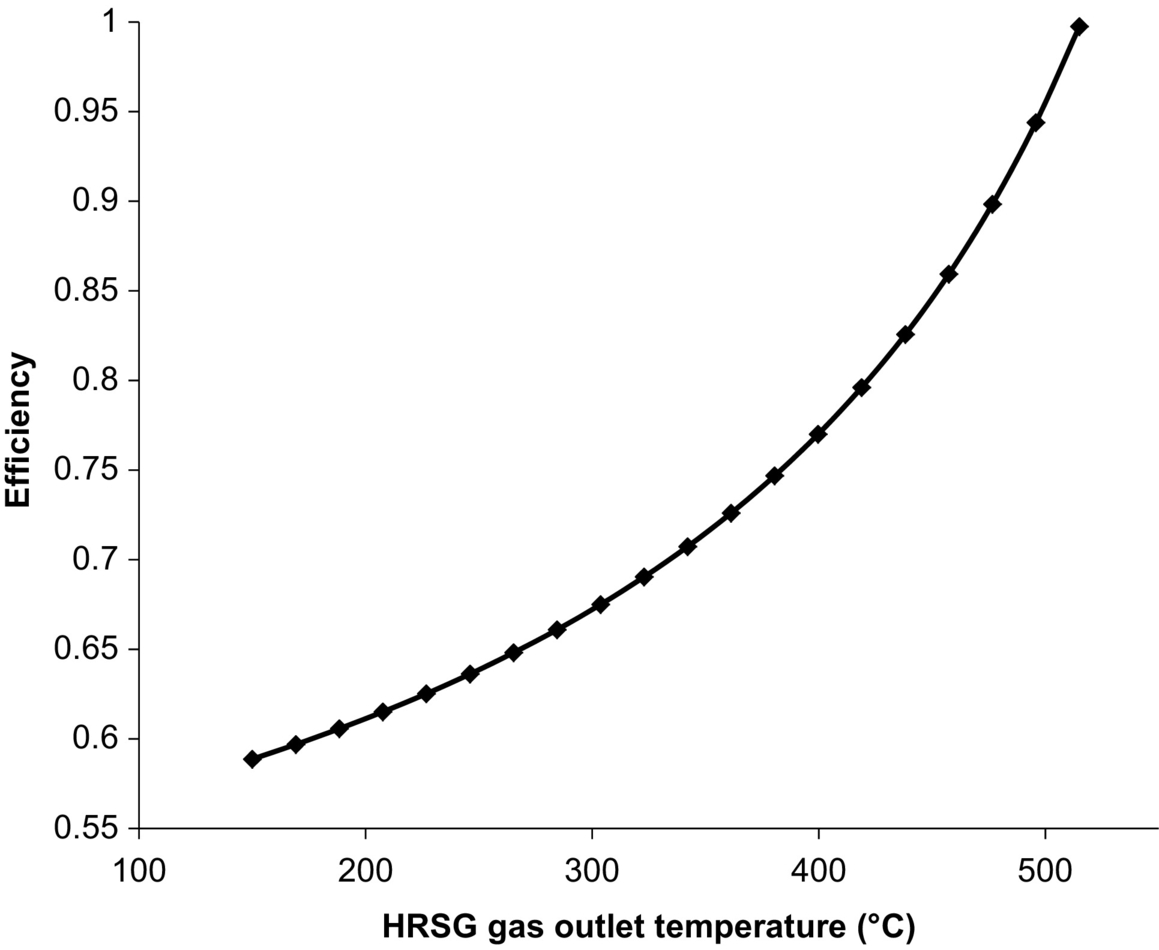

10.5.4.3 Effect of syngas temperature at the HRSG exhaust on system performance

The effect of varying syngas temperature at the exit of the HRSG on coverage ratio and net work rate is shown in Fig. 10.5. It is found that decreasing the syngas temperature at the HRSG outlet causes CR and net work output rate of the UCG system to increase. Marrero et al. (2002) attained comparable results in a study investigating optimal operating conditions of a triple power cycle that incorporated an HRSG, connected to a Rankine cycle similar to the one in the present study. Similar to the work by Marrero et al. (2002), it is found that reducing the syngas temperature at the HRSG outlet allows for increased thermal energy utilization within the HRSG, resulting in increased steam production and steam turbine output.

Higher HRSG exhaust temperatures reduce the amount of energy available for steam production, resulting in lowered steam flow rates at the turbine inlet. The thermal requirement of the CO2 capture process remains static, and the energy transferred to the auxiliary plant is decreased, with increasing temperature, which increases the portion of steam used for CO2 processing compared with the steam produced in the HRSG. As the portion of steam extracted from the turbine at an intermediate pressure increases, the flow rate through the turbine from the inlet to the low-pressure outlet is reduced, which contributes to the reduction in turbine output. In terms of power production, employment of low-temperature gas processing systems would be preferred, to allow power production to be optimized.

The system arrangement and operating conditions impose restrictions on the upper HRSG exhaust temperature. The temperature must remain below 515°C to provide the steam required by the splitter reboiler with the current model. This is a result of inadequate steam production rates within the HRSG in comparison with the requirements of the splitter reboiler. The restriction could be varied through the use of different turbine extraction conditions and reducing the process requirements. Extracting steam from the turbine at higher pressures would allow for the flow rate to the splitter reboiler to be reduced and the HRSG exhaust temperature restriction to be increased. Increasing the extraction pressure would reduce the turbine work output.

The effect of HRSG exhaust gas temperature on the auxiliary plant efficiency is illustrated in Fig. 10.6. Higher HRSG syngas outlet temperatures result in increased auxiliary plant efficiency (Eq. 10.18). Over the range temperatures considered, the efficiency varies from 59% to 99%. The efficiency increases with syngas temperature because of a reduction in the condenser losses that is a result of reduced flow rates within the condenser. The flow rate through the condenser associated with the highest exhaust gas temperature is zero, and all of the steam produced in the HRSG is used by the splitter reboiler. This suggests that the auxiliary plant could exclude the typical condenser unit and use the splitter reboiler for condensing the steam exiting the turbine. The efficiency approaches 100% due to the model utilized within this study; the assumptions made allow for all of the thermal energy transferred to the steam to be utilized in the associated processes.

10.5.4.4 Concluding comments for case study

When heat is recovered from hot syngas to supply an auxiliary Rankine cycle, sufficient thermal and electric energy are made available for use by processes associated with UCG with CCS. The combination of UCG with CCS and an auxiliary power plant demonstrates benefits in terms of reduced CO2 emissions and associated energy requirements. The combination of a Rankine cycle and UCG can mitigate CO2 emissions while improving UCG economic feasibility and increasing recoverable coal reserves.

The turbine output of the auxiliary plant, for the circumstances investigated, is greater than that required by the power-consuming processes, allowing a greater net power delivery from the UCG system considered compared with UCG systems not utilizing this arrangement.

The air injection rate affects the syngas production rate and, therefore, the energy flow rate through the HRSG. The air injection rate also affects the CO2 production rate and the associated capture and compression energy use rates. Varying the air injection rate does not affect the coverage ratio of the auxiliary plant, suggesting a linear relationship between air injection rate and the operating conditions for the plant processes. Increasing the air injection rate raises the net work output of the auxiliary system. It appears advantageous to operate this system arrangement with high air injection rates to increase the produced power, although caution is required since high air injection rates require elevated process capacities and component sizes, resulting in increased costs (even though there may be some advantages associated with economy-of-scale effects for larger systems). Air injection rates can be adjusted to optimize the system economic feasibility.

Utilization of CO2 capture and compression processes with high energy requirements has a negative effect on the coverage ratio of the auxiliary plant, which reduces the system net work output. Under certain operating conditions, an upper limit exists for the thermal requirements of the CO2 capture process; if exceeded, the system cannot supply all the required thermal energy. When CO2 capture requirements are below this limit, the auxiliary plant operates correctly and has a positive net work output over the entire range of CO2 compression energy requirements.

The temperature to which the syngas is cooled, prior to cleaning, has a significant effect on system performance. The temperature of the cooled syngas is a major factor in determining the amount of thermal energy available for steam production. When the syngas is cooled to the lowest temperature typically used in industry, the coverage ratio and the net power output of the UCG system are significantly increased relative to the base system. An upper temperature limit exists, above which the rate of steam production is too low to support the CO2 capture requirements. When the syngas temperature is set to the upper limit, the overall auxiliary plant efficiency, which includes the CO2 capture requirement, is increased due to reduced thermal losses in the condenser.

10.6 Closing remarks

Although the earth is an abundant source of coal, a significant amount is currently unrecoverable using conventional mining techniques. Coal is likely to remain used in many countries, increasing the needs for new technologies that permit more environmentally benign extraction and utilization. The use of UCG can help expand recoverable coal reserves, and the syngas it produces can be used as a fuel or chemical feedstock. Fossil fuels typically utilized in power production can then be used for other purposes, or their consumption rates can be reduced.

Numerous models have been created to simulate UCG and the various processes and phenomenon involved. Packed-bed models are applicable for highly permeable porous media. Most of the packed-bed models consider detailed physical and chemical factors, based on experimental and theoretical comparisons. The packed-bed models exhibit good agreement for gas compositions measured from laboratory experiments, but the overall relating of these models to field trials is difficult. The packed-bed and coal block approaches are mostly developed by considering one-dimensional behavior. As a result, information on cavity shape cannot be obtained from these models. The channel models have the ability to determine cavity shape and size using two- or three-dimensional analysis.

The production of excess power through implementing an auxiliary power plant, utilizing rejected heat from syngas cooling, can help provide the necessary energy requirements for CO2 capture and compression and other auxiliary processes. The combination of UCG with CCS and auxiliary power plant appears beneficial in terms of reducing CO2 and providing the associated energy requirements while potentially improving the economic feasibility of UCG and carbon capture.

UCG has the potential to store CO2 within voids created during its operation, which reduces the need for transport and storage site identification. In essence, UCG could provide a cost-effective, near-zero-carbon energy source through the use of a self-contained system with a closed carbon loop.

UCG offers a coal extraction and conversion method in a single process that avoids many of the challenges associated with conventional mining practices. Underground coal gasification has a high potential for integration with CCS using conventional methods utilized in power production due to similarities with surface gasifier units. Although the technology is not widely employed currently, additional research and testing of UCG systems will likely improve modeling and analysis methods and expand the use of UCG systems globally.