Majuba underground coal gasification project

S. Pershad; J. Pistorius; M. van der Riet Eskom Research, Testing & Development, Johannesburg, South Africa

Abstract

The Majuba UCG project has been developed by Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd (Eskom), a vertically integrated public electricity utility in South Africa. The project, located in the South African province of Mpumalanga, has been under development since 2002. It is the largest, the longest running and the most advanced UCG project outside of the former Soviet Union. The technology to the project has been provided by Ergo Exergy Technologies Inc. (Canada). The project has been targeting the provision of UCG syngas produced in Majuba coal deposit as a fuel for power generation to a CCGT power plant. The chapter focuses on technical and environmental aspects of the project development.

Keywords

Underground coal gasification; Water monitoring system; Energy resource; Electricity; Syngas; Eskom; Pilot plant operations; Gasifier rehabilitation

14.1 Introduction

South Africa is well endowed with coal, solar, wind, and nuclear energy resources but less so with hydro, gas, and oil. This is changing as new discoveries are confirmed, such as the potential of shale gas in the Karoo region of South Africa. In the regional context, South Africa has a broader diversity of energy resources, with a far greater proportion of gas and hydro (including the enormous potential of the Inga river in the Democratic Republic of Congo). All these indigenous energy resources compete, and their competitiveness is judged by factors such as their accessibility, cost, environmental footprint, and proximity to market. Furthermore, imported energy resources (such as LPG, LNG, and nuclear fuel) could be competitive.

Underground coal gasification (UCG) presents a significant future energy source opportunity for South Africa. Within the South African context, this is recognized in two key energy documents, namely, the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030 (2012) and the recently released draft Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) 2016.

With specific reference to coal, UCG and electricity, the NDP states the following:

Cleaner coal technologies will be supported through research and development and technology transfer agreements in ultra-supercritical coal power plants, fluidized-bed combustion, underground coal gasification, integrated gasification combined cycle plants, and carbon capture and storage, among others.

The draft RSA IRP (November 25, 2016) states the following:

UCG technology therefore allows countries that are endowed with coal to continue to utilize this resource in an economically viable and environmentally safer way by converting coal into high value products such as electricity, liquid fuels, syngas, fertilizers and chemical feedstock. While the process has previously been criticized for generating large quantities of hydrogen as a useless by-product, hydrogen is now in demand as a feedstock for the chemical industry and shows potential as an alternative fuel for vehicles. The development of this technology and the viability of its implementation are still at a nascent stage and ongoing research needs to be undertaken.

Research and development:

Research and development should focus on innovative solutions and in particular on solar energy, as this has the greatest potential to address electricity challenges for small-scale energy consumers in a fairly short timeframe. Solar energy also has the potential to address the need for energy access in remote areas; create semi-skilled jobs; and increase localization. More funding should be targeted at long-term research focus areas in clean coal technologies such as CCS and UCG as these will be essential in ensuring that South Africa continues to exploit its indigenous minerals responsibly and sustainably. Exploration to determine the extent of recoverable shale gas should be pursued and this needs to be supported by an enabling legal and regulatory framework.

The Department of Energy is accountable for the compilation of a draft South African Integrated Energy Plan (IEP). A draft (IEP) (DOE, 2016), was released in 2016 for public comment with a view to replace the previous IEP 2010, which comprises many elements as indicated in Fig. 14.1. These elements govern the need for, and timing of, all energy technologies. The primary factors considered when proposing any energy technology would be its commercial maturity, cost, and emissions. Secondary factors such as water consumption, localization, job creation, and technology transfer also determine technology suitability.

The South African IEP (and specifically the IRP component for electricity) sets the entrance criteria for all energy technologies, including UCG.

Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd (Eskom) is a vertically integrated public electricity utility in South Africa, with primary energy provided by coal, nuclear, hydro, wind, photovoltaic, and biomass. Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd is South Africa's primary electricity supplier and is a state-owned company (SOC) as defined in the Companies Act, 2008. The company is wholly owned by the South African government, through the Department of Public Enterprises (DPE). Eskom generates ~ 90% of the electricity used in South Africa and ~ 40% of the electricity used on the African continent.

The electricity supply industry in South Africa consists of the generation, transmission, distribution and sale of electricity, and importation and exportation thereof. Eskom is a key player in the industry, as it operates most of the baseload and peaking capacity, although the role played by independent power producers (IPPs) is expanding. Eskom operates 28 power stations, with a total nominal capacity of 42,810 MW, composed of 36,441 MW coal-fired stations, 1860 MW of nuclear power, 2409 MW of gas-fired, 600 MW hydro and 1400 MW pumped storage stations, and 100 MW Sere Wind Farm.

It includes four small hydroelectric stations, which are installed and operational, but not considered for capacity management purposes (Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd, 2016).

UCG is one of several potential clean coal technologies being researched and developed by Eskom, to align with the South African IRP for electricity generation.

14.2 Overview of Eskom's Majuba UCG project

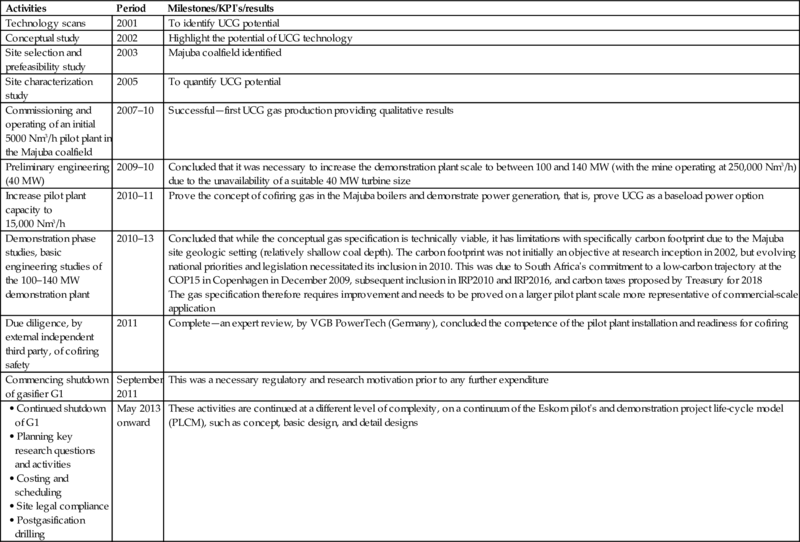

Eskom's UCG research project was initiated by the South African UCG pioneer Dr. Mark van der Riet in 2002 to develop the science of UCG technology against modern standards and regulations. Eskom highlighted UCG's potential in an internal Coal Technology Conceptual Study in 2002, and this led to a site selection and Prefeasibility Study in 2003, a Site Characterisation Study in 2005, the successful commissioning of a pilot plant in the Majuba coalfield in January 2007, and the successful testing of the equipment for cofiring of UCG gas in one of the Majuba Power Station boilers in October 2010. Eskom's Pilot Plant ran successfully through to September 2011, after which decommissioning commenced as the pilot had successfully qualified the technology performance, and the following step was to quantify performance with a demonstration plant (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1

Eskom Majuba UCG project phases

| Activities | Period | Milestones/KPI's/results |

| Technology scans | 2001 | To identify UCG potential |

| Conceptual study | 2002 | Highlight the potential of UCG technology |

| Site selection and prefeasibility study | 2003 | Majuba coalfield identified |

| Site characterization study | 2005 | To quantify UCG potential |

| Commissioning and operating of an initial 5000 Nm3/h pilot plant in the Majuba coalfield | 2007–10 | Successful—first UCG gas production providing qualitative results |

| Preliminary engineering (40 MW) | 2009–10 | Concluded that it was necessary to increase the demonstration plant scale to between 100 and 140 MW (with the mine operating at 250,000 Nm3/h) due to the unavailability of a suitable 40 MW turbine size |

| Increase pilot plant capacity to 15,000 Nm3/h | 2010–11 | Prove the concept of cofiring gas in the Majuba boilers and demonstrate power generation, that is, prove UCG as a baseload power option |

| Demonstration phase studies, basic engineering studies of the 100–140 MW demonstration plant | 2010–13 | Concluded that while the conceptual gas specification is technically viable, it has limitations with specifically carbon footprint due to the Majuba site geologic setting (relatively shallow coal depth). The carbon footprint was not initially an objective at research inception in 2002, but evolving national priorities and legislation necessitated its inclusion in 2010. This was due to South Africa's commitment to a low-carbon trajectory at the COP15 in Copenhagen in December 2009, subsequent inclusion in IRP2010 and IRP2016, and carbon taxes proposed by Treasury for 2018 The gas specification therefore requires improvement and needs to be proved on a larger pilot plant scale more representative of commercial-scale application |

| Due diligence, by external independent third party, of cofiring safety | 2011 | Complete—an expert review, by VGB PowerTech (Germany), concluded the competence of the pilot plant installation and readiness for cofiring |

| Commencing shutdown of gasifier G1 | September 2011 | This was a necessary regulatory and research motivation prior to any further expenditure |

• Planning key research questions and activities • Costing and scheduling • Site legal compliance • Postgasification drilling | May 2013 onward | These activities are continued at a different level of complexity, on a continuum of the Eskom pilot's and demonstration project life-cycle model (PLCM), such as concept, basic design, and detail designs |

Eskom licensed the ɛUCG technology from Ergo Exergy Technologies Inc. (Canada). Ergo Exergy's UCG experts have been closely involved in all technical aspects of Majuba UCG project since its inception; successful gradual transfer of ɛUCG technology expertise and know-how helped to build up the skill set of Eskom UCG team.

The lengthy technology gestation period unfortunately occurred during a time in South Africa when the country evolved from having surplus generating capacity to where there were critical shortages. Likewise, within the same time frame, the international community evolved from having scant regard for carbon emissions to the current imperative of decarbonizing. These evolving circumstances affected Eskom's UCG project significantly, and the project therefore needed to also change its strategic drivers.

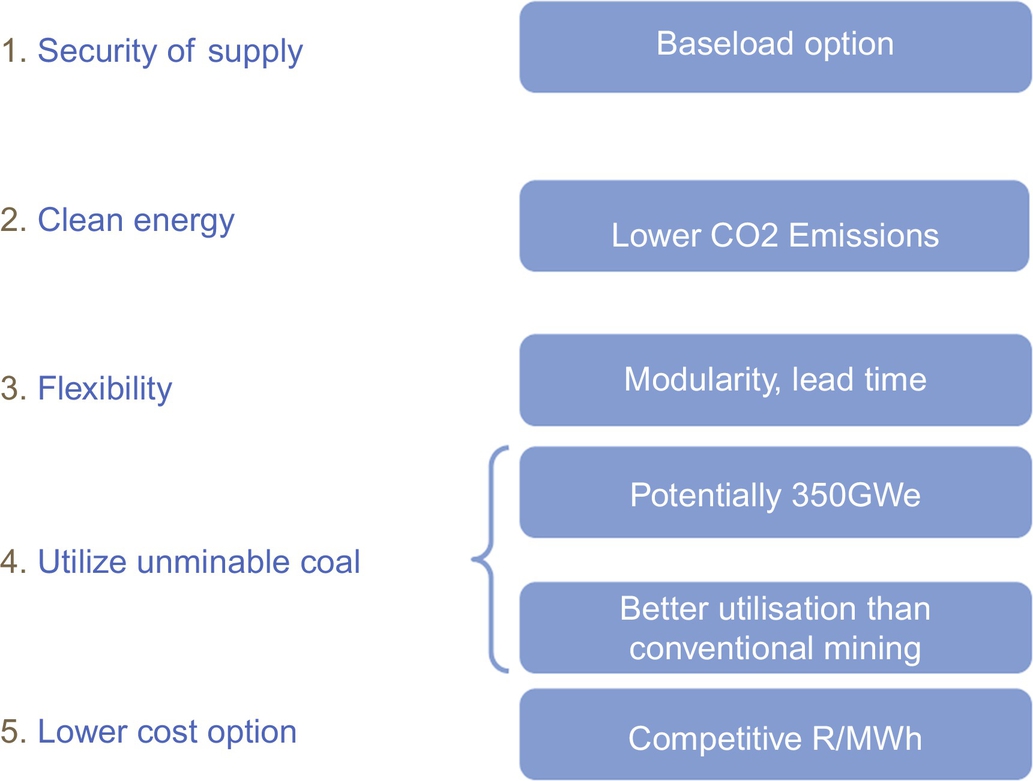

The strategic drivers applicable in the period 2007–12 are illustrated in Fig. 14.2.

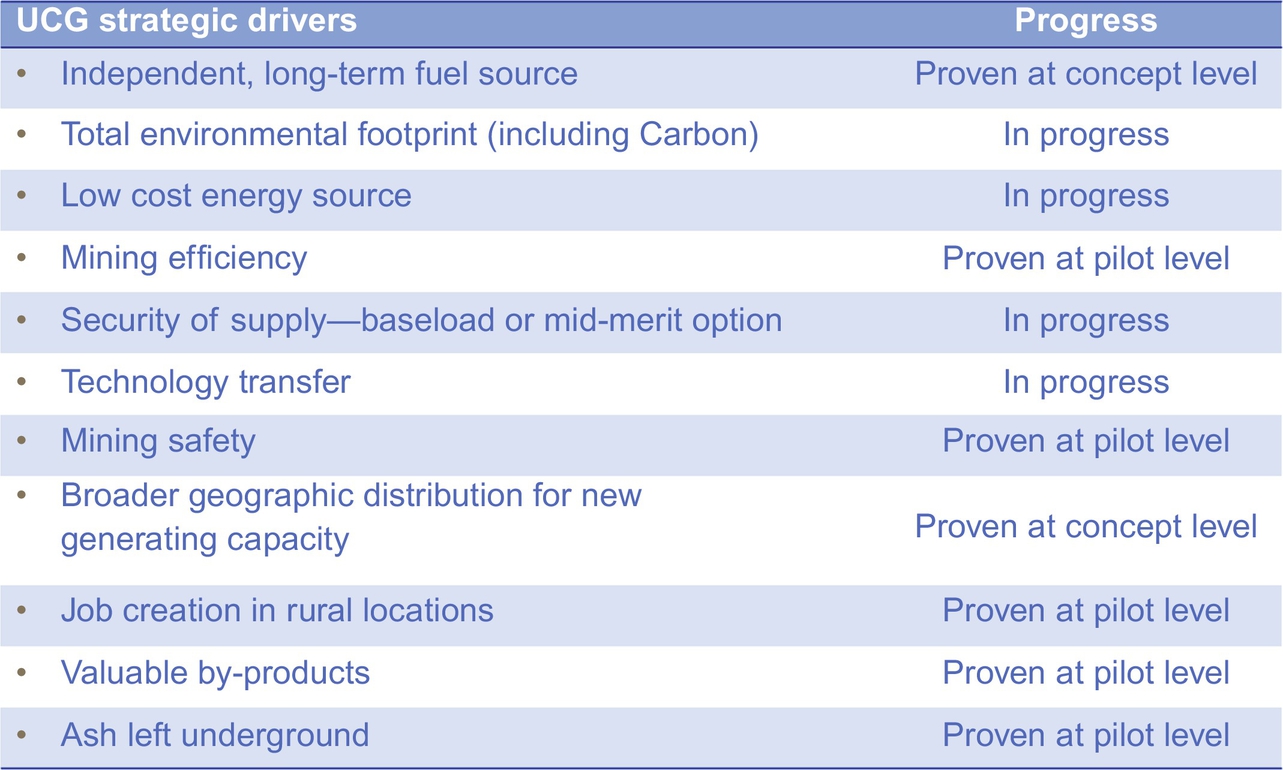

In 2012, the project strategic objectives again changed to be in step with local factors and South Africa's international commitment to decarbonize electricity production. The new strategic drivers and progress therein are reflected in Fig. 14.3.

Table 14.1 illustrates the various phases of Eskom's Majuba UCG project.

Eskom's initial intent and the objective of the pilot plant was to firstly produce and secondly cofire the UCG gas, at the Majuba UCG site, into the adjacent Majuba Power Station boilers. This would naturally not have added new generating capacity to the grid, but merely swopped fuel source from coal to coal-derived syngas. However, due to the shortage of generating capacity in South Africa that became apparent in the early 2000s, Eskom's UCG commercial objective evolved to adding new generating capacity by firing the gas produced at the Majuba UCG site in an open-cycle gas turbine (OCGT) or a combined-cycle gas turbine (CCGT), depending on the load required.

In 2015, the project encountered circumstances within the country and company that led to company-wide budget restrictions, affecting all noncore operations. Owing to the success of the UCG project and its continued strategic importance, Eskom board granted a revised mandate to seek partnership and to convert the existing UCG infrastructure into a commercially viable power-generating plant. This phase intent is still currently in the internal commercial and regulatory process, with the end objectives and scale to be defined with the new partner(s).

14.3 Site selection & prefeasibility phase, 2002–03

In 2002, Eskom completed a scoping study report, which described the technology review, communications with UCG technology suppliers, and potential sites considered (Van Eeden et al., 2002). The study identified and recommended Ergo Exergy Technologies Inc. of Canada (Ergo Exergy) as the technology supplier. Ergo Exergy's variation of UCG technology is based on lessons learnt in the extensive UCG research and operations in the former-Soviet Union and successfully trialed in the Chinchilla I UCG project, Australia (1997–2006) and several others international projects. The Ergo Exergy variation of UCG technology is termed the Exergy UCG or ɛUCG. With Ergo Exergy's assistance, six potential sites were short-listed as suitable for UCG.1 The Majuba site located on farm Roodekopjes 67HS, in the Amersfoort district of Mpumalanga, South Africa, was the site eventually chosen from the selection process, for reasons given below:

1. Eskom owned the mineral rights and substantial surface rights.

2. The proximity of Majuba Power Station enabled consideration of cofiring the gas in to the boilers, to offset coal imports.

3. The Majuba coal seam met the UCG conceptual technology requirements, as the coal seam had an ~ 250 m average depth and 3 m average thickness. The coal seam was also known to have low permeability, which was also seen as an advantage for containing the UCG process.

4. Dolerite intrusions were acknowledged to have broken the coal reserves into smaller blocks, which were anticipated to be a benefit (from the point of view of containing the process) or possibly a problem (from the point of view of disrupting UCG mining).

5. The Majuba coal deposits were extensive, with many adjacent blocks, capable to support a large UCG-based power generation development.

The very difficult geologic conditions in the coalfield were a concern to Ergo Exergy. Eskom noted this but concluded that from a research perspective, this was a suitable challenge for UCG, implying that if it worked successfully in this coalfield, then it could conceivably work in any other more favorable coalfield.

Many other favorable features became apparent after the studies with the Majuba site began, such as given below:

– Eskom had access to an extensive geologic database of more than 400 exploration boreholes drilled in the coalfield, for the defunct Majuba colliery.

– Eskom also had access to extensive hydrogeologic study data, and geophysics conducted on the site.

– There was existing Majuba colliery infrastructure, comprising extensive and unused buildings, workshops, living quarters, etc.

– The proximity of Majuba Power Station proved invaluable, due to their frequent assistance and support, from the use of their medical and emergency services, through to the loan of heavy equipment such as mobile crane.

– Majuba Power Station also had an extensive hydrocensus of surrounding water bodies, compiled over many decades and updated regularly. There were also two ambient air monitoring sites in proximity, with several decades of data. In addition, there was also an existing meteorologic database over several decades.

– During the construction of Majuba Power Station, a detailed flora and fauna study had identified endangered red book species living in the area, the sungazer lizard (Cordylus giganteus). A special sanctuary had been successfully established adjacent to Majuba Power Station for the relocation of this and other animal species.

– No cultural heritage places or archeological finds were identified.

The Majuba site was subsequently approved for development of the project into the next phase, site selection and prefeasibility (Blinderman and Van der Riet, 2003) (Fig. 14.4).

14.4 UCG site description

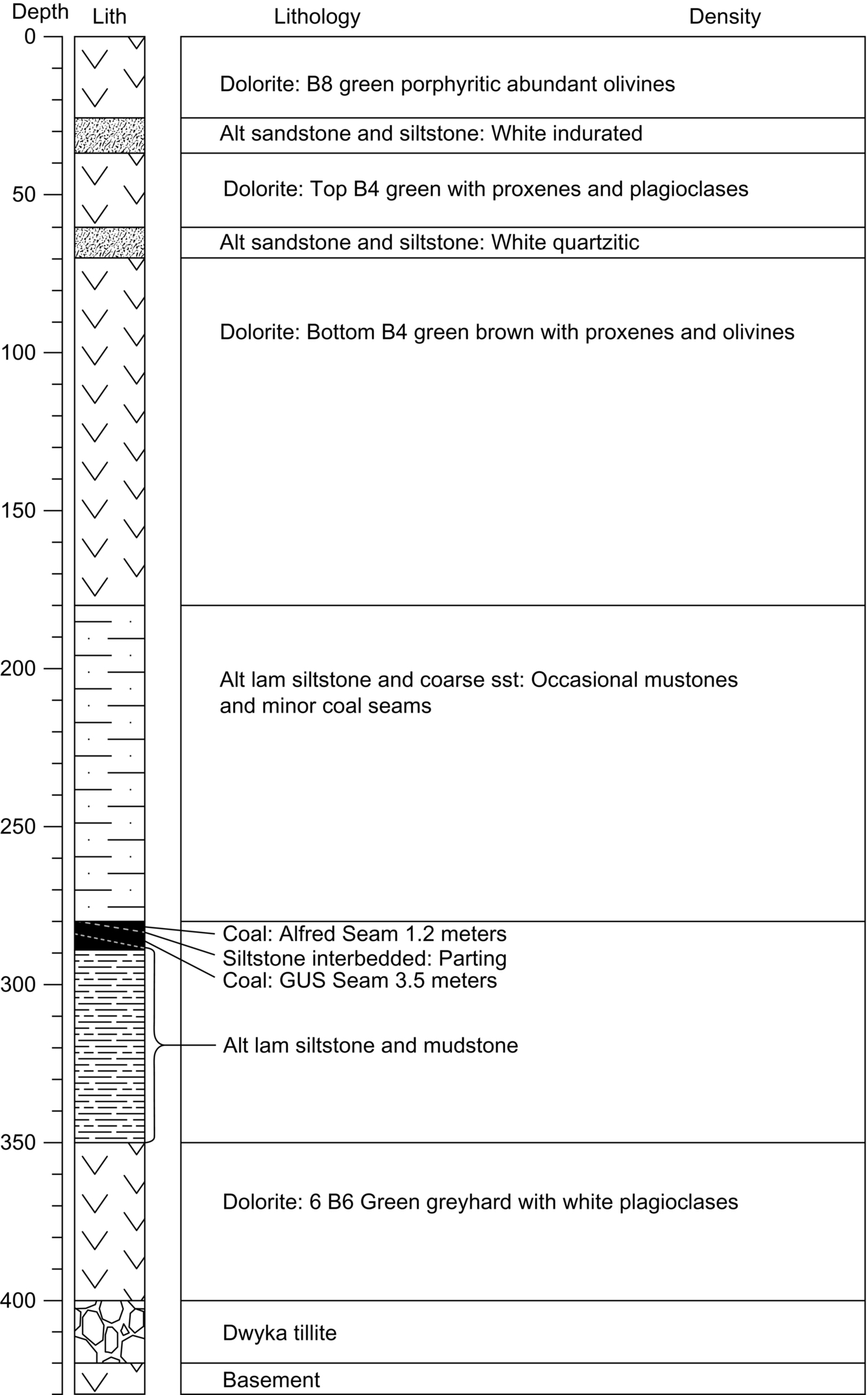

The Karoo Supergroup hosts all South African coal deposits and ranges from the Late Carboniferous to Middle Jurassic age (320–180 Ma). It was formed in the great Gondwana basin that is composed of parts of South Africa, Antarctic, Australia, India, and South America. Coal deposits in South Africa are restricted to the area east of 26°E and in relation to the Majuba area, falls within the Vryheid Formation of the lower Ecca Group (Snyman, 1998).

The Majuba coalfield is situated in Amersfoort district of the Mpumalanga province in South Africa and comes into the immediate vicinity of Eskom's 4100 MW Majuba Power Station in the south. The surface of the area consists of rolling hills, with drainage courses forming occasional cliff features. Elevation varies between 1593 and 1775 AMSL. The relief in the northern area is greater with deeper incision of water courses, resulting in occasional large cliff features and rocky terrain. Drainage is generally good via numerous intermittent streams. Average annual rainfall is ~ 490 mm. The rainy season is generally from October to March with peak season falling in January. There may be 125–150 mm rainfalls in one single day.

Most of the area is pastoral land, providing grazing for sheep and to some extent cattle. Small areas are under cultivation, generally for maize.

The Majuba coal deposit forms a part of the Ermelo coalfield, which covers an area of 115,000 km2. The coal resources for conventional mining in the coalfield have been estimated in the range of 8 billion t, with most resources being undeveloped.

The coal measures consist of three sequences: (a) the underlying Dwyka Formation, a tillite, which lies unconformably on the basement rocks and varies in thickness from 1 to 25 m; (b) the Pietermaritzburg Formation, a massive dark shaley siltstone about 20 m thick; and the Vryheid Formation, which is the thickest unit that consists of predominately upward coarsening cycles that are capped by coal seam formation. The only seam of economic importance is named the Gus seam, which is a subbituminous seam attaining a maximum thickness of nearly 5.0 m.

The floor of the Gus seam is a laminated carbonaceous siltstone and the roof a coarse grained interpreted as an erosive fluvial channel but changes laterally to a laminated siltstone and finer grained sandstone, which represents the interchannel zones.

Above the Gus seam the Alfred seam, if present, can develop up to 1.5 m in thickness. The parting between the Gus and the Alfred seams varies from 0 to more than 10 m.

The coal resources are severely intruded by Jurassic and early Cretaceous dolerite units. These intrusive events are divided into three categories:

– Transgressive sills

– Near-vertical dikes

Fig. 14.5 illustrates a simplified stratigraphic column for the Majuba coalfield.

The intrusion of dikes and sills was governed mainly by lithostatic pressure, and intrusions occurred along cracks and fissures caused by tension. These dolerite intrusions form a complex network within the coal bearing Vryheid Formation of the Ecca Group, leaving these sedimentary rocks of sequences of succession structurally and metamorphically disturbed. The structural disruptions of the coal seams are mainly due to the intrusion of dolerite dikes and sills. However, small-scale graben-type faulting and fracturing within the coal seams also occur (Du Plessis, 2008).

The Majuba coal deposit, and specifically the selected site, was found to be technically suitable for applying UCG technology. Calculated primary reserves for UCG operations within the farm Roodekopjes 67HS amounted to ~ 106 million t, enough to supply UCG gas for 400 MWe of power generation in Majuba Power Station for ~ 43 years (or 28 years for 600 MWe; 28 years being similar to the remaining life of Majuba Power Station).

The application of UCG technology to the Alfred/Gus coal seam of this deposit was deemed technically justified and feasible. Specific conditions of the Majuba coal deposit, such as multiple dolerite intrusions, were considered not to create insurmountable problems for UCG operations. A multitude of technical issues concerning the UCG application and adaptation were intended to be resolved during the next research phase, that is, site characterization and pilot plant operations on the selected site.

Detailed process modeling of UCG proper, gas cleanup, transportation, and boiler performance showed that cofiring UCG gas with coal in the boilers of Majuba Power Station was technically feasible and likely to lead to confirmation of an alternative and abundant local fuel supply. It was concluded to be technically feasible to reticulate and integrate UCG.

It was found that at the selected site, the conditions of coal occurrence would be conducive to conducting UCG operations in the Alfred/Gus seam at the depth below 250 m, without causing an impact on valuable groundwater resources. The subsidence would be managed in order to minimize the surface disturbance and avoid undermining surface-water sources and alluvial aquifers.

14.5 Site characterization phase, 2005

In 2005, a detailed characterization of the site was conducted (Blinderman et al., 2005).

The site characterization phase covered prospecting, geologic and hydrogeologic investigations, and rock mechanics modeling of the overburden behavior at the target UCG site. The coal seam in the process area was also tested under “cold” conditions with controlled air and water injection to evaluate UCG potential, and extensive UCG-specific program of laboratory gasification testing of coal core samples were completed (Figs. 14.6 and 14.7).

The results of site characterization indicated that the site was favorable for applying ɛUCG technology at Majuba, and they create a solid foundation for design and construction of a UCG pilot plant. They also confirmed the findings and recommendations of the site selection and prefeasibility report produced in 2003 as follows:

– The Majuba coal deposit, and specifically the selected site, was found to be technically suitable for applying ɛUCG technology for gas production.

– The application of ɛUCG technology to the Alfred/Gus coal seam of this deposit was deemed technically justified and feasible. Specific conditions of the Majuba coal deposit such as multiple dolerite intrusions were not anticipated to create insurmountable problems for UCG operations.

– It was found that at the selected site, the conditions of coal occurrence would be favorable for conducting UCG operations in the Alfred/Gus seam at the depth below 250 m without causing an impact on valuable groundwater resources. The subsidence would be managed to minimize the surface disturbance and rule out a possibility of undermining surface-water sources and alluvial aquifers.

In conclusion, from a technical perspective Ergo Exergy recommended proceeding to construction and commissioning of the pilot plant using the newly created test wells in the target area for process and monitoring wells.

The commercial in-house review concluded that the energy cost compared very favorably with the Eskom baseline power-generating technology of pulverized fuel combustion. The spacing of ɛUCG wells and electricity draw were identified as major technical risks influencing the energy cost, and the subsequent phases focused on optimizing these factors.

The site characterization phase recommended the following specific actions:

1. Further work should be done to evaluate water quality in the actual coal seam and in any aquifers that may be identified in the overlying or underlying rock.

2. Future packer tests should be conducted at higher water injection pressures to produce more extensive data on coal seam permeability.

3. Supervision of the drilling and logging and reporting of any significant events are critical.

4. Water and rock mechanics monitoring systems will be essential.

5. The high yield of polyaromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) compounds arising from the laboratory coal pyrolysis tests indicated caution in handling UCG tars and condensate as such compounds could be toxic.

6. Further research into the pyrolysis behavior of the coal was required using larger sample masses.

7. The overall conclusion was that the project is viable from technical and environmental viewpoints. It was recommended to proceed with the project to pilot plant operation.

The following findings motivated the request for approval of the pilot phase of the Majuba ɛUCG project:

1. The geologic interpretation of the UCG site area remained unchanged, after the drilling of eight additional boreholes. Drilling difficulties included deteriorating dolerite and fissures in the overburden, which dictated the requirement for the drilling, reaming, and casing to take place within 10 days to avoid borehole deterioration and collapse. Vertical drilling and coring produced samples of rock and coal that enabled evaluation of seam and overburden properties with detailed analyses and testing.

One nearly vertical dolerite dike had been intercepted by directional drilling, and from general understanding of the microgeology, it was perceived beneficial for UCG operations. The directional hole was still advancing at the time of the report. It was anticipated to form a backbone of the future pilot plant design and assist larger UCG operations in the future.

2. The old hydrogeologic study had very scarce information on the aquifers existing in the area, with exception of the alluvial upper aquifer that is well-known and easily accessible. There were insufficient data at that time on occurrences of groundwater in the coal seam and the deep aquifers in the overburden and underburden. The groundwater monitoring system was finished prior to construction of the Pilot plant in the next phase. The main findings at that stage were the following:

– Water levels in the upper alluvial aquifer did not differ from those anticipated in the site selection and prefeasibility report

– Holes into the coal seam filled with water within several days and water levels reached ~ 50 m from the surface. This evidence indicated the presence of a confined aquifer associated with the coal seam.

– Packer tests using the standard methodology for conventional mining exploration are not relevant to UCG. Tests need to be conducted at injection pressures that allow an extended water flow to render the results more representative.

– There were not enough data to suggest any trends in regional groundwater flow, anisotropy of the permeability in the coal and the upper aquifer.

– There were multiple occasions when drilling water circulation had been lost in the overburden rock, specifically within the overlying dolerites. It was deemed important to understand the structure and extent of the fractured zones that served as the water sinks.

3. Based on the rock mechanics modeling, both analytic and numerical, the following conclusions were drawn:

– Immediate roof collapse could be expected to initiate from (at most) a 20 m UCG cavern span. Indications were, however, that caving would initiate from (at most) an 8 m cavern span.

– The worst-case scenario indicated that the thick intact layers of overlying dolerite would fail beyond a 100 m cavern span.

– The maximum height of collapse was not reasonably expected to exceed 110 m (for a 250 m cavern span).

– No caving through to surface was expected if the “intact” dolerite layers did not contain major jointing or geologic structural weaknesses.

– As the UCG cavern span reaches 10–15 m, the first immediate roof layers will collapse. As the span increases, the extent of the goaf will reach a height of 15–40 m. The overlying rock layers will then tend to become dislodged along preexisting joints and settle on the goaf, recompressing it, when the span is ~ 80–100 m. Due to the presence of thick and strong sandstone layers and the thick dolerite sills, no meaningful surface subsidence is expected. The cavity below the base of the sill will gradually fill up by progressive failure of the overlying sill over a long period of time, continuing for several months or years.

4. ɛUCG air and water pressure cold tests were conducted using three process wells and surrounding exploration and monitoring holes. The primary purpose of the testing was to obtain data on gas and water permeability of the coal seam and surrounding strata. Results of air testing showed considerable gas permeability of the coal seam in the areas between process wells. This indicates that reverse combustion linking (RCL) can be used for linking the process wells during the pilot plant stage. The water test results confirmed the very high permeability of the coal seam between the process wells. Due to limitations of water pumping equipment and unexpectedly high-water permeability of the coal seam in the process area, it was impossible to reach high pressures required to achieve Aquasplitt linking conditions.

5. Bench-scale testing compared the gasification of Majuba coals with Chinchilla coal from the then Ergo Exergy ɛUCG site in Queensland, Australia. The CO2 gasification reactivity of the Chinchilla coal as measured by a thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) was four times higher than Majuba coal. However, in the Ergo Exergy fixed-bed reactor, the Chinchilla coal took more than twice as long to burn through the same distance along the reactor length. The Australian coal peak combustion temperature was also lower by some 160°C than the Majuba coal, and rate of combustion was 2.6 times slower. The Majuba coal had higher levels of CO and H2 but lower levels of CH4 compared with the Australian coal. The Australian coal produced more aliphatic volatile organic compounds (VOCs), whereas Majuba coal produced more PAH compounds and light gases (H2 and CH4).

6. In summary, from a technical perspective the results confirmed suitability of the Majuba test site for UCG operation, in accordance with ɛUCG technology.

14.6 Pilot phase (2007—present)

14.6.1 Introduction

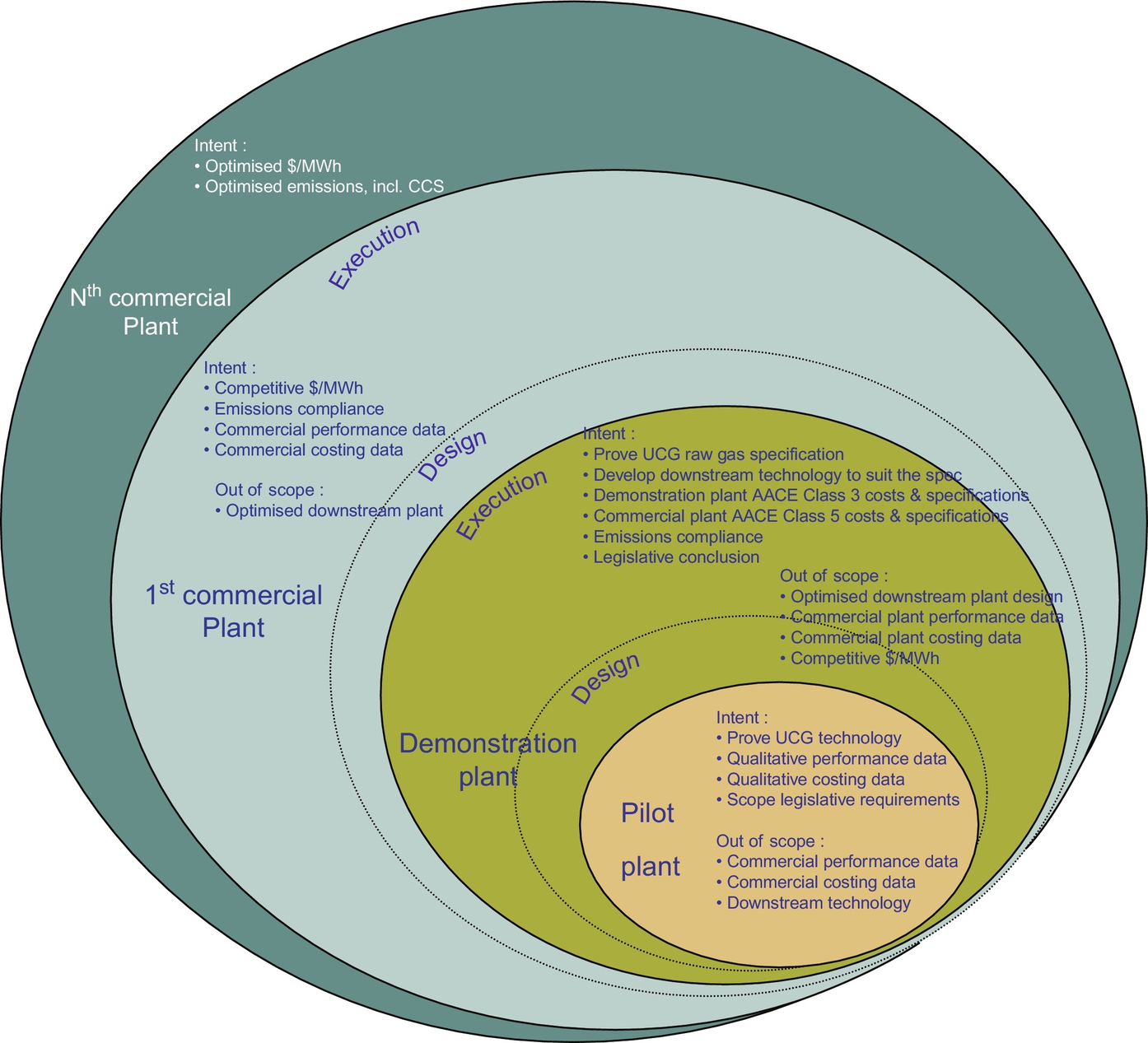

The findings and recommendations from the preliminary investigations and site characterization studies were considered when developing the strategic objective of the pilot plant. Fig. 14.8 illustrates the intent of the pilot plant and the out-of-scope items that were not intended to be researched. It is important to understand the out-of-scope items as these often lead to an overexpectation of technology development outcomes.

The objective of the pilot phase was to qualitatively determine the feasibility of the application of ɛUCG technology at the Majuba field and within the South African economic and legislative environment. This was done by the construction, commissioning, operation, and controlled shutdown of a pilot ɛUCG plant at the Majuba site.

In order to prove the ɛUCG technology via performance qualification, the pilot plant objectives were as follows:

1. Production of a synthesis gas via the means of UCG. The key sub activities were the following:

– Drill, case, and complete injection and production wells.

– Link injection and production wells.

– Ignite the coal seam.

– Develop and sustain the gasification reaction.

– Collect and further analyze the UCG gas.

2. Determine gasifier operational responses and parameters.

3. Determine the properties of gaseous and liquid products.

4. Controlled shutdown, with postgasification drilling and monitoring of impacts.

5. Prove environmental and safety performance of the technology.

6. Develop and maintain the pilot facility for training, experimentation, and data generation.

7. Controlled shutdown, with postgasification drilling and monitoring of impacts.

14.6.2 Methodology

The pilot plant was broken into three phases in order to meet the objectives at various stages and scale through the life of the project, as described in Table 14.1. The scope of work of the pilot phase 1a and pilot phase 1b was the construction, commissioning and operation of a 5000 and 15,000 Nm3/h ɛUCG pilot plant, respectively (Fig. 14.9). The UCG pilot plant can be generically broken down into two areas of operation:

2. UCG surface plant

The mining operation consisted of various wells that were drilled and cased to ensure that the gasification chamber was sealed off from the surrounding environment. The wells either were fed with air (as an oxidant for the gasification process) or were gas producers (Figs. 14.10–14.12).

Surface plant infrastructure included the air compressor plant, gas and air piping network, gas-liquid separation plant, condensate treatment plant, raw water dam, and condensate evaporation pond.

For the design and construction of surface plant equipment, a model gas specification was developed by Ergo Exergy using proprietary ɛUCG model based on the unique characteristics of the Majuba UCG site, such as coal quality, geology, hydrogeology, and rock mechanics. The specification for the 5–15,000 Nm3/h pilot plant included noncondensable gases (CnHm, CO2, CO, H2, H2S, Ar, and N2), condensable vapors (H2O, NH3, C6H6O, C7H8O, C10H8, and C7H8), and particulates (coal fines, ash, and solidified tar). Process modeling produced gas composition at well head and at the gas treatment plant (GTP) outlet. The modeling showed notably low particulate content of the gas (1.5 mg/Nm3) that in practice turned out to be much lower.

14.6.3 Findings

In January 2007, following extensive preparation fieldwork, the coal was successfully ignited. Hours after ignition, the first ɛUCG syngas was produced from the Majuba coalfield.

During the first year of operation, gas production was stable, proving the feasibility of producing ɛUCG syngas from the Majuba coalfield.

Operational parameters were altered within the limits of the available plant and equipment to determine the gas properties at various operating conditions and thereby optimize the syngas quality and production. In June 2007, a 100 kW power generator was modified to run on 80% UCG gas and 20% diesel. The diesel was predominantly required for lubrication; however, the generator ran on 100% syngas for a period of 2 weeks. This is remarkable as an example of using syngas for power generation in technically simple and very cost-effective manner (Figs. 14.13 and 14.14).

By 2008, the UCG operations needed to expand to a larger scale. This was done without interrupting the gas production, by drilling additional production wells in the G1 panel and systematically linking them to the existing underground reactor.

Gas field operational parameters were again tested at a larger scale with multiple injection and production points. UCG gas production was sustained at a consistent production rate and stable gas quality for an extended period of time. An initial strategic objective of the Majuba UCG project was to cofire syngas into a 710 MW pulverized coal boiler at Majuba Power Station. In October 2010, the first syngas was successfully cofired for a period of time. During that period, the infrastructure and controls of cofiring syngas and coal had been tested (Fig. 14.15).

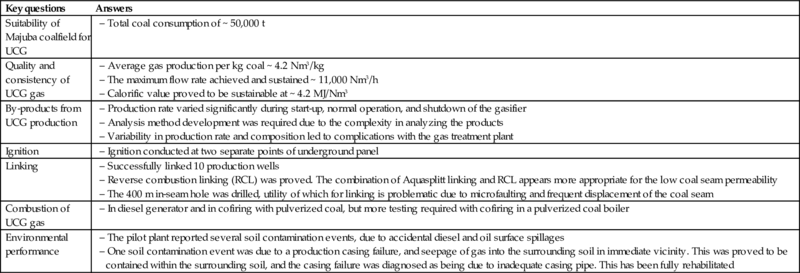

During the pilot plant operation from 2007 until shutdown initiated in 2011, key research questions were answered, within the capability and scale of the pilot plant (Table 14.2).

Table 14.2

Key research questions and answers

There were also a number of operational problems encountered and successfully resolved:

1. Drilling through the horizontally layered sugary dolerites, penetrating the vertical dolerite intrusions intercepting the coal seam, gasifier entering combustion state, and autoignition of the coal seam.

2. The cofiring trial successfully proved the capability of the installed equipment. Subsequent expert review by the VGB (Germany) concluded the competence of the installation and readiness for cofiring.

3. No UCG-related safety and health accidents have been recorded during pilot plant operations. The pilot plant proved to be a steep learning curve in terms of safety. UCG essentially combines three industries (mining, petrochemical, and power), with their attendant standards and applicable legislation. The Eskom UCG pilot plant was the first in South Africa and the longest running in the Western World. UCG does not easily fit within existing mining regulations and acts and has required negotiation, leniency, and concessions from regulators. The overall response and support for the technology has been very positive, and there has been a willingness to allow it to proceed as a research endeavor due to the tremendous potential it offers while learning regulatory requirements. This is necessary for any first-of-a-kind (FOAK) plant (Figs. 14.16–14.18).

4. The specific technical lessons learnt from the UCG pilot research plant include the following:

– Thorough site characterization is essential for assessing UCG viability at a conceptual level (comprising geologic, hydrogeologic, rock mechanic, and geotechnical).

– Baseline environmental tests are essential prior to commencing any UCG activities on a site. These comprise testing of soil, water (surface and subsurface), air, flora and fauna, and noise.

– Site characterization and pilot plant are absolutely necessary to determine the potential of a coalfield for UCG technology.

– A water monitoring system is essential prior to any UCG activity, so as to establish baseline and production data. The Majuba UCG water monitoring strategy is described in more detail in the following subsection.

– UCG generally offers an inventory of methodologies for each activity, not all of which will work on a specific field or at a specific location. Their selection is based on skill, and furthermore, they must be trialed during the pilot phase to select the appropriate approach for each site.

5. The generic lessons learnt from the Majuba UCG pilot plant have been extensive:

– A core team of competent and multitasking professionals and support staff is essential for a UCG pilot plant, as the technology crosses many different disciplines and traditionally separate industries.

– There is serious concern with regard to mineral rights, due to overlapping property licenses (such as coal-bed methane) for a given single coal resource.

– The rapid evolution of legislation (particularly in the South African context) requires the attention and dedication of a senior professional, to continuously monitor compliance. This is essential even for a UCG pilot plant.

– Evolving legislation during the UCG piloting period proved significant enough to change the research scope and strategic drivers with corresponding budget and schedule impacts.

– Stakeholder engagement is critical to inform and consult. Stakeholders include staff, management, the community, NGOs, academics, regulators, legislators, and even other UCG developers nationally and worldwide.

– The Eskom UCG project set out to prove several strategic drivers, and the project findings confirmed that the technology works and is operationally and strategically relevant for Eskom and South Africa.

– Any UCG developer needs to accept the inherent challenges with commercializing technology in their own, unique coal geology. While proved on many sites internationally, technology should not be transferred to other sites without substantial studies, testing, and piloting.

– The potential value of the technology far outweighs its uncertainties.

– Based on the performance of ɛUCG technology during feasibility and pilot studies that were conducted under a special Ergo Exergy MFS License, Eskom acquired from Ergo Exergy a General ɛUCG License for development of commercial ɛUCG-based power projects in South Africa (Fig. 14.19).

14.6.4 Recommendations

1. A revised 70,000 Nm3/h pilot plant was motivated and approved by the Eskom board in December 2012 (and ratified in January 2013), to continue the research and quantify UCG performance at adequate scale for commercial uptake.

2. The intent of this size panel was to prove the technology performance for subsequent commercial plant development. The specific reasons for this size are outlined below:

– The 5000–15,000 Nm3/h pilot plant is operated as a linear (one-dimensional) gasifier. As the coal is consumed, the cavity grows and the quality of the gas decreases. The reason for the decrease in quality is the large cavity reduces the velocity of air and the airflow pattern is not turbulent; thus, the air does not contact fresh coal surface, and all the air is therefore not consumed in the process. Essentially, a three-dimensional reactor is required that makes use of multiple injection and production points. This ensures that new sources of oxidant and gas offtake points are available as needed and that sufficient gas velocity is maintained to ensure turbulence across a face of fresh coal. Once the coal has been consumed, roof cave-in must be facilitated, essentially keeping the cavity at an optimal size for intense air/coal contact. Without cave-in, over time, the gasification reaction will deteriorate as the reaction consumes its own products, due to the constantly expanding “dead space” in a larger cavity and abundance of unused free oxidant and syngas at high temperatures.

– The concept engineering design was completed to provide an indication of what has been done and what still needs to be done in terms of the operation of a nominal 70,000 Nm3/h UCG power plant. The plant design consisted of UCG mining, gas and condensate treatment and power generation. The plant intended to generate 28 MW (gross) electricity, making use of reciprocating engines (Fig. 14.20).

14.6.5 Water monitoring strategy

The establishment of a water monitoring system is essential prior to any UCG activity, to establish baseline data and to plan production. The Majuba UCG water monitoring and protection strategy was designed by the ɛUCG technology provider Ergo Exergy during early stages of prefeasibility and site characterization based on the then available hydrogeologic information. It was further adjusted to site conditions taking into account new hydrogeologic information gathered during pilot plant operation in collaboration of hydrogeology advisor Golder Associates, Ergo Exergy, and Eskom (Love et al., 2015).

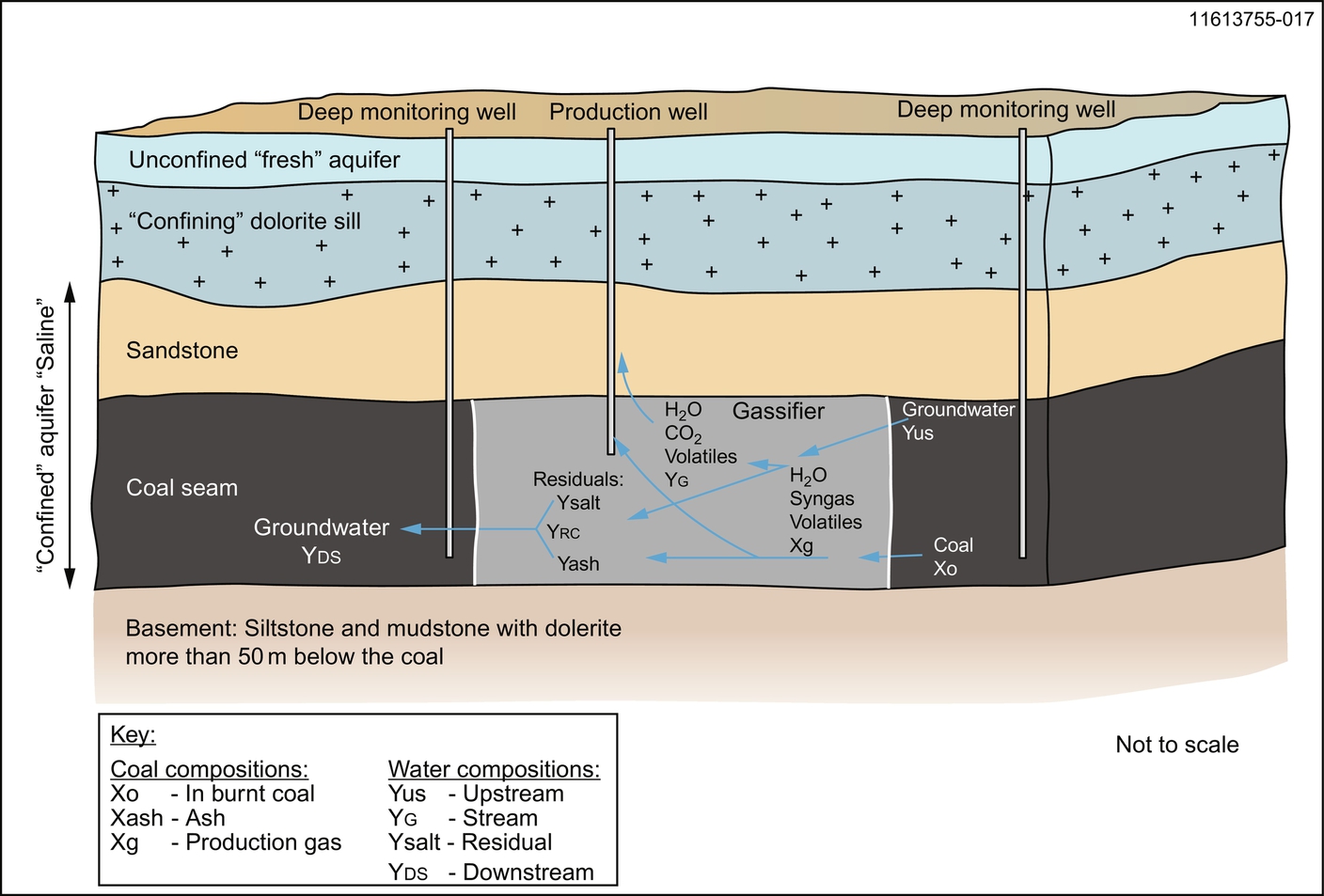

The groundwater system at the Majuba UCG site comprises a deep coal seam aquifer, a lower intermediate aquifer, an upper intermediate aquifer and a shallow aquifer (see Fig. 14.21). The preUCG baseline water quality studies proved the coal seam aquifer is unsuitable for domestic or agricultural use. The potential source sits within the coal seam aquifer, and the principal receptor is the shallow aquifer, which is used for agricultural purposes—although not at the Majuba UCG site. The overlaying dolerite sill is seen as a natural confining layer between the source—the coal seam aquifer where gasification is taking place—and the receptor, the shallow aquifer. Pathways from the source to the receptor could, in principle, be developed in preparation to, or during gasification, allowing interconnectivity between the coal seam aquifer and the shallow aquifer.

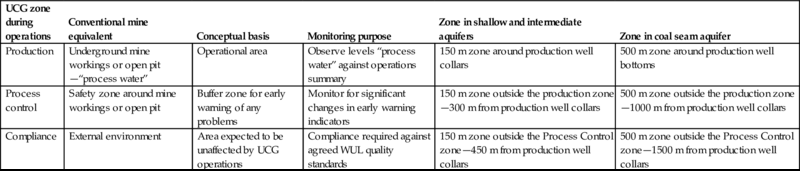

Different hydrogeology monitoring zones are identified, as indicated in Table 14.3.

Table 14.3

Majuba UCG hydrogeology monitoring zones

| UCG zone during operations | Conventional mine equivalent | Conceptual basis | Monitoring purpose | Zone in shallow and intermediate aquifers | Zone in coal seam aquifer |

| Production | Underground mine workings or open pit—“process water” | Operational area | Observe levels “process water” against operations summary | 150 m zone around production well collars | 500 m zone around production well bottoms |

| Process control | Safety zone around mine workings or open pit | Buffer zone for early warning of any problems | Monitor for significant changes in early warning indicators | 150 m zone outside the production zone—300 m from production well collars | 500 m zone outside the production zone—1000 m from production well collars |

| Compliance | External environment | Area expected to be unaffected by UCG operations | Compliance required against agreed WUL quality standards | 150 m zone outside the Process Control zone—450 m from production well collars | 500 m zone outside the Process Control zone—1500 m from production well collars |

The layout of these monitoring zones will obviously need to be expanded as UCG production develops. Within the process control zone, the approach is to detect signs of possible contamination and to investigate and mitigate such contamination immediately. The compliance zone contains groundwater that should be minimally affected by the UCG operation and to which compliance standards apply. Once UCG has ceased, monitoring will continue to be required during the post-operation recovery phase. During this phase, the water table will be recovering (rebounding), and it is expected that water quality in the production zone will be recovering due to dilution. It is proposed that during this phase, the production zone becomes part of process control zone and the compliance zone is retained without alteration. Once the site enters the closure and long-term monitoring phases, the monitoring zonation and approach depends on the closure plan approved by the legal regulator.

14.7 Demonstration phase studies

14.7.1 Introduction

The Eskom UCG pilot plant ran successfully for 4½ years, purposefully sited on one of the most geologically complex coalfields in the country so as to test the technology suitability. The positive findings of the pilot plant led to the subsequent approval of the feasibility study into a demonstration plant. A basic front-end engineering design (FEED) of a 100–140 MW demonstration plant (250,000 Nm3/h) was undertaken in the period 2010–12 with Black & Veatch (the United States).

Eskom's demonstration plant intent was to prove the potential of using the Majuba coalfield to sustainably produce sufficient UCG gas to fuel a 2100 MW (gross) integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) plant. The risks associated with such a large FOAK technology investment would be mitigated by designing, building and operating a demonstration plant of sufficient scale to form a module of the commercial plant, and proving operations of the high-risk units such as the gas turbine (in open-cycle mode only) and GTP.

14.7.2 Methodology

A power plant basic engineering design and GTP FEED was performed with the following scope. The GTP would treat 250,000 Nm3/h of UCG syngas for use as fuel in a 100–140 MW OCGT demonstration scale plant.

The tasks performed during the power plant basic engineering design were as follows:

– A site arrangement drawing for the demonstration plant, which included the power plant, GTP, common area, and evaporation ponds.

– Heat balance calculations for several load conditions and lower syngas heating values.

– A water mass balance diagram that depicted the water usage and flow rates of the various water and wastewater streams in the facility.

– Preliminary process flow diagrams for the major plant systems that depict typical system configuration, equipment redundancy, major flow paths and valves, etc.

– Overall demonstration plant electric one-line diagrams showing the generator, transformers, and auxiliary electric system down to the 400 V level.

– A major equipment list to show the required pieces of equipment for the open-cycle power plant.

– An AACE Level 3 cost estimate and schedule.

– It is critically important to conduct the engineering design study at the appropriate level, with the above details to fully appreciate the overall project complexity, risk mitigation, and total project costs.

14.7.3 UCG gas specification

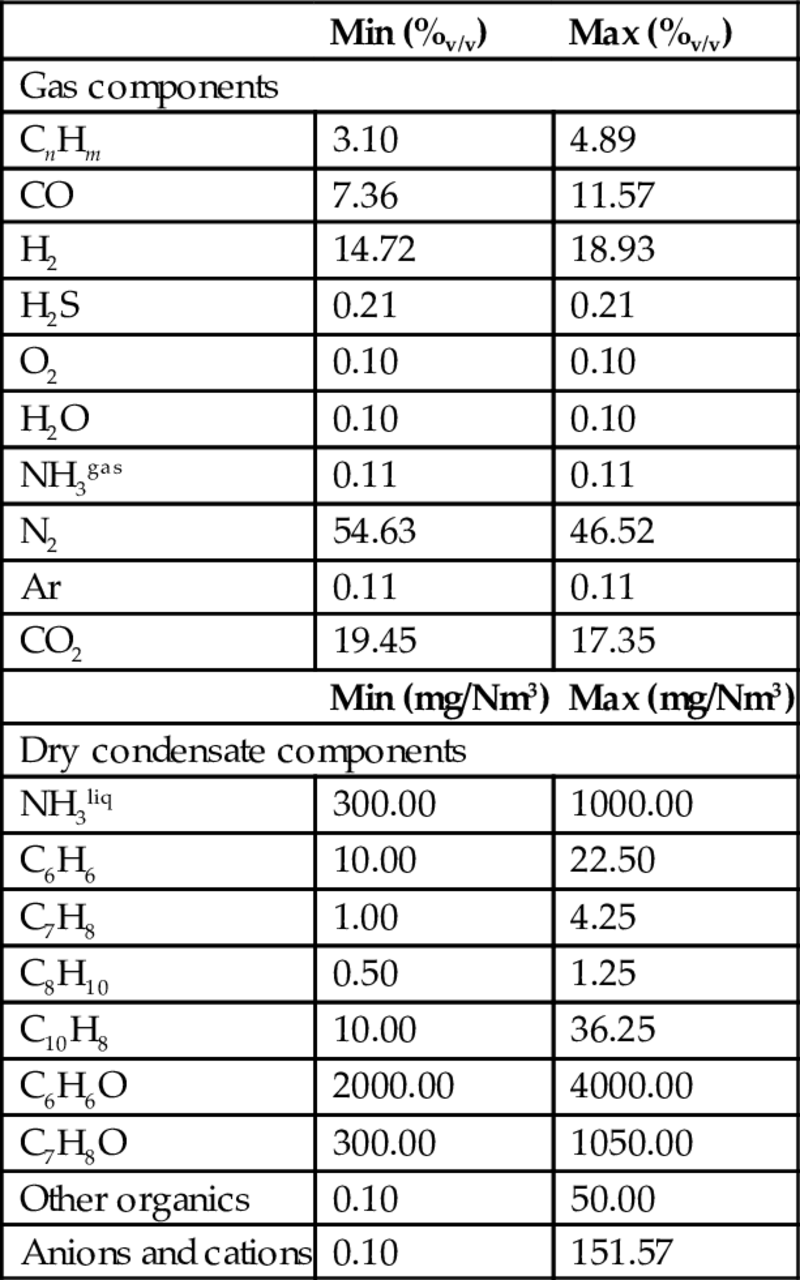

The gas specification for the demonstration pilot plant was modeled by Ergo Exergy based on previous results and the outcomes of pilot plant operation and adjusted to operational conditions of a large-scale demonstration plant. The optimal gas composition produced by modeling was within limits given in Table 14.4.

Table 14.4

ɛUCG demonstration plant syngas specification

| Min (%v/v) | Max (%v/v) | |

| Gas components | ||

| CnHm | 3.10 | 4.89 |

| CO | 7.36 | 11.57 |

| H2 | 14.72 | 18.93 |

| H2S | 0.21 | 0.21 |

| O2 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| H2O | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| NH3gas | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| N2 | 54.63 | 46.52 |

| Ar | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| CO2 | 19.45 | 17.35 |

| Min (mg/Nm3) | Max (mg/Nm3) | |

| Dry condensate components | ||

| NH3liq | 300.00 | 1000.00 |

| C6H6 | 10.00 | 22.50 |

| C7H8 | 1.00 | 4.25 |

| C8H10 | 0.50 | 1.25 |

| C10H8 | 10.00 | 36.25 |

| C6H6O | 2000.00 | 4000.00 |

| C7H8O | 300.00 | 1050.00 |

| Other organics | 0.10 | 50.00 |

| Anions and cations | 0.10 | 151.57 |

14.7.4 Findings

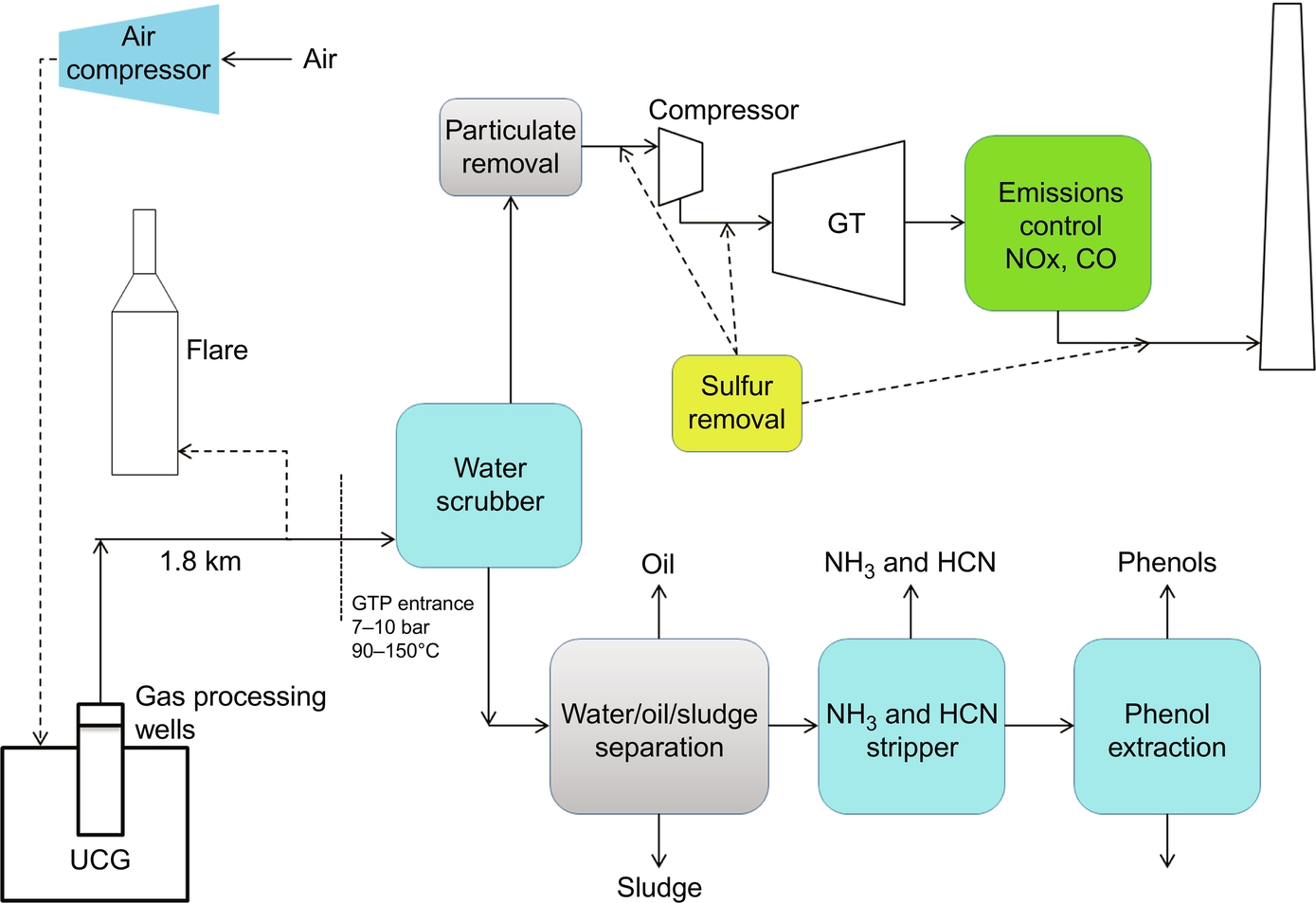

The function of the GTP in Fig. 14.22 was to treat the raw UCG syngas and its associated condensate to meet the OCGT feed requirements while adhering to environmental and safety requirements.

A Level 1 milestone schedule was developed based on an engineer, procure, and construct (EPC) execution methodology. An overall project schedule duration of 44 months was calculated, starting with preliminary engineering activities and ending with final acceptance of the plant in month 44. An approximate ± 25% accuracy capital cost estimate was developed for the OCGT, GTP, and common facilities, based on the level of accuracy of information available. Costs for equipment, systems, materials, etc. that are shared between the OCGT and GTP were placed in the common category.

The following major risks were identified during the design process:

– UCG syngas and condensate specification and consistency: The demonstration plant design was completed based on a model gas specification, the sustainability of which had not been adequately tested during the pilot plant operations. The initial pilot plant was operated as a one-dimensional reactor; however, during commercial operations, the UCG would be operated as a three-dimensional reactor. This will have a major effect on the gas and condensate specification and consistency. Deviations from the model gas specification will therefore have a direct influence on the process efficiency of the demonstration plant. As a consequence of this uncertainty, the demonstration plant design had to cater for a worst-case scenario and was consequently overdesigned.

– Technology selection: None of the technologies specified in the secondary treatment plant had been specifically tested on the UCG condensate before. Of specific concern was the sequencing batch reactor that caters for biological treatment of hydrocarbons, due to the selection of the microorganisms to be used. This selection is dependent on the quantity and quality of ammonia, sulfur, chloride, and phenol in the condensate and the aeration requirements.

– Auxiliary power consumption: The auxiliary requirements of the GTP and OCGT are relatively high and should be optimized in future plant design.

A power plant basic engineering design was produced for the 100–140 MW UCG OCGT demonstration project. The following risks were identified for the power plant basic engineering design:

– UCG syngas and condensate specification and consistency: The water and salt balances are based on a model specification and have not been adequately tested. Thus, if there is a significant change in the condensate composition during operation, the demonstration plant would not be able to effectively process the condensate produced.

– Auxiliary power requirements were high, and optimization led to a higher-quality gas specification.

The above findings are to be expected with the evolutionary development for FOAK technology.

14.8 Majuba gasifier 1: Shutdown & verification drilling

14.8.1 Introduction

The verification drilling together with environmental monitoring of the UCG postgasification system forms a final, critical part in proving the hydrogeologic integrity of the spent gasifier in a mining technology “cradle to grave” approach. In order to apply UCG on a commercial basis, it needs to be proved that the used UCG cavities are hydrogeologically stable and that no contamination plume spread can occur from the cavity to surrounding groundwater sources over substantial periods of time (as determined by the South African water and mining regulators). Part of the controlled shutdown process forming a part of ɛUCG technology and long-term rehabilitation and monitoring strategy is to prove that the coal side walls, char, and ash residue in the cavity is capable of absorbing any remaining contaminants (if any) and that the level of contaminants decrease over time.

Even with existing experience of what actually remains in the UCG cavity and what the long-term effects and impacts of this could be on the surrounding environment, projections for any specific geology and hydrogeology settings must be tested at the specific site.

Eskom's UCG project successfully completed the operation of a pilot facility near Majuba Power Station. Further research activities together with environmental monitoring are being carried out to gain a full understanding of the requirements for safe shutdown and assist in finalizing of future UCG plant shutdown procedures. The initial approach was to allow the cavity to be cooled down by natural influx of the surrounding groundwater into the cavity. This shutdown process took longer than originally anticipated and eventually had to be assisted with supplementary water injection. Water injection required a lengthy process with fully detailed mitigation strategies to obtain the necessary approval from the South African water regulator. The UCG cavity was officially declared shutdown in June 2015.

14.8.2 Verification drilling objectives

Verification drilling was subsequently initiated (and is still ongoing) as part of the postgasification research program, in order to investigate the gasification area and to establish the following:

– The extent of the gasification cavity by confirming the boundaries of the cavity. This would indicate control over the growth, direction, and size of the cavity and that mining was not “blind.” The information is also required to provide regulatory feedback for prospecting and mining rights to confirm the extent of the reserves utilized and payment of royalties.

– The physical and chemical properties of the postgasification cavity in various positions. This information will be used to verify the understanding of the main mechanisms driving the UCG process, its extraction efficiency, and overall performance.

– The upper lithology's changes in physical and chemical properties. This information will be used to verify the initial geologic, hydrogeologic, and rock strength models that are required for safe and successful long-term mine planning of commercial operations.

The verification wells that are being drilled will also subsequently serve as environmental monitoring wells to fully understand the long-term impacts of a depleted UCG cavity.

14.8.3 Verification drilling interim conclusions

This section presents interim conclusions from the verification drilling program as it is still ongoing as this text is being prepared. Key conclusions to date are as follows:

– The verification drilling program has been successfully initiated to address key UCG technology “cradle to grave” operational an environmental issues.

– The first three wells have been successful in verifying the gasification cavity boundaries and showing control over the process reliably limited location of fire within the coal seam. This information will be used in discussions with the South African regulators for Minerals, Environment and Water in order to clarify new legislation that will be required to govern UCG processes in the future.

– The deformation and softening of the upper lithologies in the test core samples indicate that sufficient information from the following three wells will be obtained to verify characterization phase rock strength models. These models are greatly important during the mine planning stages and operation of the UCG process. Hence, validation of them at the end of gasification is critical for future use.

– The packer testing to establish changes in the porosity and permeability of the different lithologies was unsuccessful to date. The methodology has been revised going ahead to incorporate the use of the drill rig to perform the tests on the remaining wells. This information is critical in validating and finalizing the project hydrogeologic models.

– The chemical results of the liquid samples provide confidence of UCG technology viability going forward, since there is no plume migration out of the cavity. This means that both the gasification process and the subsequently accumulated water body have been safely contained within the spent UCG cavity.

– The liquid samples from the verification wells analysis are relatively clean when compared with typical gasification reaction related chemicals and contaminants. It has always been assumed that some contaminants would be trapped in the spent cavity, post gasification; however, an estimation of these levels was very difficult. The results are providing the first quantifiable insights into what really remains within an old UCG cavity. The extended shutdown period promotes the breakdown, dilution, and absorption of some of the chemicals leading to very low observed levels. This is extremely significant for continual development of the UCG technology. Monitoring of these wells will be continued for any changes in composition over time as part of the long-term water use license requirements.

– In summary, the postgasification conditions of the UCG cavity are stable, with no signs of plume spread. The overall composition of the liquids remaining in the cavity is in line with typical coal seam aquifers, and the baseline analyses performed on the site prior to any UCG activity. Water quality monitoring will be continued over time to refine and assure the water quality models used to predict long-term impacts.

– To date, no postgasification UCG technology contamination risks have been identified. The results indicate that the controlled shutdown and rehabilitation operational design is adequate and functional.

The verification drilling program should be completed in order to fully address the outstanding key post gasification UCG technology conclusions (Fig. 14.23).

14.9 Commercialization phase

14.9.1 Introduction

Due to current capital constraints within Eskom, a mandate was granted for the UCG project to secure a partnership to the following:

– Leverage the substantial Majuba UCG pilot plant asset and intellectual property and commercial module design completed.

– Secure funding to complete the current project.

– Assist with commercializing the technology.

The guiding principle assumed is that the partnership intends to be profitable, and the first phase of development will deliver an acceptable return on equity in order to attract a suitable partner.

14.9.2 Methodology

In preparation for executing the partnership mandate, it was necessary to constitute a team that would analyze and evaluate the business proposition ahead of seeking a partner via Eskom's commercial process. This team also included external business analysis experts to critically assess the project status. The analysis considered the following aspects:

1. Market situational analysis describing the UCG value chain, regulatory requirements, competitor technologies, and UCG development competitors in SA.

2. Strategic alignment outlining the changes in the environment that has had an impact on the strategic drivers, the project life-cycle model, the strategic drivers, and the alignment of these with Eskom's strategy.

3. Market context and opportunities analysis highlights the benefits and opportunities that development of the UCG project would have.

4. UCG competitive positioning aims to demonstrate that UCG has the potential to be competitive in terms of gas supply and UCG to power at a generating cost comparable with other technologies.

5. UCG development status and research intent providing background to the development from inception to date and the research approach and potential development options.

6. Majuba UCG development asset valuation providing information on the cost to date and the potential value that could be extracted.

7. Business model options that describe the high-level options to extract maximum value from the development.

8. Majuba UCG partnership plant estimated cost that provided the high-level capital and operating cost to develop the UCG partnership plant based on a set of assumptions forming the base case.

9. Commercial considerations highlighting some of the key factors that would need to be elaborated in continuing the development path or road map.

10. Advocacy strategy providing high-level guidance on the partnership options that will be explored further in the partnership and procurement strategy.

11. Risks and timescales

14.9.3 Key finding

The key finding of the partnership assessment is that there is sufficient information derived from the Majuba UCG project to demonstrate that the project and technology are attractive and should be commercially developed.

With the above finding in mind, Eskom will pursue the development of UCG technology with a partner.

14.10 Conclusions

The following conclusions can be drawn from Eskom's 14 years investment in UCG research and development:

1. The 2007–10 pilot plant operation has successfully proved the application of UCG technology on the Majuba coalfield at the maximum scale of 15,000 Nm3/h.

2. The demonstration feasibility study proved that UCG gas is technically feasible for power generation. However, the design of the demonstration plant could not be optimized without a further, adequate scale demonstration of UCG technology.

3. A larger (nominal 70,000 Nm3/h) gas production was proposed and built to complete the quantification of the technology performance and prepare the technology for a large-scale commercialization.

4. The initial economics and financial computations completed in-house demonstrate that the technology is commercially viable in comparison with competing technologies, from a gas production and electricity generation perspective.

5. UCG can have a synergistic relationship with conventional coal mines, as the technology requires coal resources that conventional miners would not consider economically viable. Conventional miners target coal seams at less than 300 m depth for economic reasons, whereas UCG is the converse as it can work at deeper levels and in fact requires depth for higher process efficiency.

6. Eskom has acquired a ɛUCG technology license from Ergo Exergy Technologies Inc. of Canada for South Africa, which enables it to develop as many UCG plants as required. Given Eskom's accumulated experience at the Majuba pilot site and advancement down the learning curve, subsequent sites can be developed more rapidly and in partnership with Eskom.

7. UCG brings opportunity for using the ɛUCG gas for several different industries (i.e., polygeneration), with significant capability of capitalizing on synergies between them.