UCG commercialization and the Cougar Energy project at Kingaroy, Queensland, Australia

L. Walker Phoenix Energy Ltd., Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Abstract

The Kingaroy project operated by Cougar Energy was one of a number of UCG projects planned for commercial development in Queensland, commencing with a pilot burn to demonstrate gas production that was initiated in March 2010. Following measurement of small, short-lived traces of benzene in one monitoring well and a subsequent high reading supplied as the result of a laboratory mix-up of samples, the project was issued a shutdown notice from the Queensland Government. This chapter describes the geologic and hydrogeological work undertaken for the project, the sequence of ignition, well failure and groundwater monitoring that led to the subsequent actions taken by the Government. The chapter also discusses the importance of establishing a clear groundwater monitoring protocol as part of the establishment of an overall UCG regulatory system.

Keywords

Underground coal gasification; Queensland; Syngas; Cougar Energy; Kingaroy; Casing design; Groundwater; Benzene; Rehabilitation; UCG policy; Environmental approval

15.1 Introduction

The Kingaroy project was developed by Cougar Energy Ltd., a company founded in 2006 with the sole purpose of commercializing the UCG process in Australia, with an initial focus on power generation in Queensland. The company's activity formed part of the resurgence of interest in UCG technology, which occurred in Australia between 1999 and 2013 and had flow-on effects internationally.

While the Kingaroy project was short-lived, as described later in this chapter, it served the purpose of concentrating attention on the range of factors involved in advancing an initial “pilot burn” into a commercially viable project, of which none has yet been established outside the historical work undertaken in the former Soviet Union (FSU), which reached its peak some 50 years previously. Factors such as government regulation and project finance are only fully addressed when a commercial project is planned, as are technical requirements such as the design of a commercial UCG facility and the matching of gas composition to end use.

To understand the genesis of the Kingaroy project and its impact on the commercialization of UCG technology in a wider context, it is necessary to review the prior history of UCG activity in Australia and its impact on planning for the project. An appreciation of this history is likely to be significant for successful project developments in the future.

15.2 Historical background in Australia

Although a number of studies of the UCG process and its potential in Australia were undertaken in the 1980s (Walker, 1999), the first active trial was undertaken by Linc Energy Ltd., which was founded by the writer in 1996. The approach to applying the technology in Australia rested on the conclusion that the only commercial sized UCG operation ever developed was that undertaken as part of the long-term UCG program in the FSU, which reached its peak in the 1960s. At the Angren UCG facility (now in Uzbekistan), syngas was produced (in 1965) at a rate of approximately 1200 billion kcal/a (Gregg et al., 1976) that, in a modern combined cycle power plant, would generate approximately 60 MW of power, and overall, more than 10 million tonnes of coal were gasified at that location (Burton et al., 2006). This compared with less than 100,000 tonnes of coal gasified in all UCG trials undertaken outside the FSU up to the late 1990s (Burton et al., 2006).

As a result of this assessment and after a number of visits to the Angren site, Linc Energy negotiated a technology agreement with Ergo Exergy Technologies Inc. of Canada to apply their expertise gained in the FSU to Linc's projects. This culminated in the planning for the first UCG field trial in Australia at a site near Chinchilla, Queensland.

After grant of a coal exploration license, then a mineral development license (MDL) as required under the then current mining law, Linc Energy entered into an agreement in June 1999 with CS Energy Ltd., a Queensland Government-owned power generator, to cofund (with the assistance of an Australian Government research grant) the development of a pilot UCG demonstration plant at Chinchilla, which, if successful, was to be expanded to produce gas for use in a gas turbine with an output of approximately 40 MW (Walker et al., 2001).

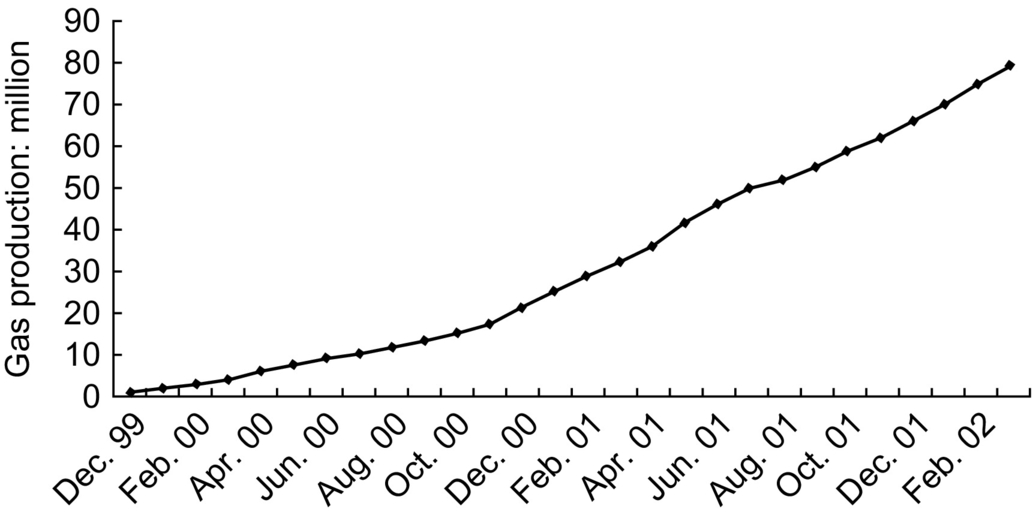

At that time, the initial focus was almost exclusively on ensuring that quality syngas production was achieved. Given the gap of some 10 years since the end of the major US research program on UCG and cessation of the European effort some 3 years earlier, it was clear that failure to produce syngas on a consistent basis would most likely result in a rapid termination of UCG interest in Australia. Following signing of the agreement with CS Energy and preliminary site characterization and site investigation work, air injection, and subsequent ignition, the first gas production was achieved in December 1999 (Walker et al., 2001). The continuous nature of gas production at the Chinchilla site is illustrated in Fig. 15.1, with the gas calorific value averaging about 5 MJ/m3 over this period. Approximately 35,000 tonnes of coal were gasified, making it by far the largest UCG demonstration undertaken outside the FSU at that time.

Perhaps more importantly, it was undertaken with no evidence of any environmental impact, particularly in relation to potential contamination of groundwater aquifer systems from the products of gasification. Blinderman and Fidler (2003) reported benzene levels in the coal seam within 50 m of the UCG gasifier area of approximately 10 ppb, and a similar reading was obtained approximately 200 m away as a result of the high directional permeability resulting from cleat structures in the coal seam. These data were obtained after completion of the controlled shutdown process in 2002. While no subsequent data have been published to indicate potential longer-term decay of this benzene level, there have been no reports of residual benzene in the coal resulting from the demonstration. The authors at the time quoted experience in the FSU showing that chemical concentrations in the coal seam “tend to return to the baseline levels over 3–5 years after the end of gasification,” which supports the concept of rehabilitation of the coal seam over a period of time.

By mid-2000, when the initial goal of successful gas production had been achieved, Linc Energy and CS Energy commenced discussions about advancing the demonstration plant into the power generation phase. Additional process wells were added to maintain the operation at minimal cost, while CS Energy undertook an in-house review of the technical and economic issues involved in advancing the project. These discussions culminated in the preparation of a joint review report early in 2002 confirming the viability of the technology; however, CS Energy required Linc Energy to seek third-party funding for the agreement to be maintained. Such funding was unable to be provided in the time required by CS Energy, who subsequently took effective control of Linc Energy in mid-2002, ordered a controlled shutdown of the operation, and subsequently sold out from the project to new investors. Ergo Exergy terminated its agreement with Linc Energy for the project at Chinchilla in November 2006.

The inability to raise project funding at the time could be attributed to a number of factors:

• An unfavorable investment climate, post the events of 9/11 in 2001 in the United States.

• Low energy prices (oil price at US $20–30 per barrel).

• Perceived investment risk, with Linc Energy being the first mover with a commercial UCG project development proposal.

• Lack of the demonstration of syngas cleanup to confirm its suitability for gas engines or gas turbines.

• Low rate of return for a first phase 40 MW power plant due to low energy prices in Queensland, with competition from much larger coal-fired power stations.

• Growing competition from coal seam gas (CSG) explorers for use of local coal deposits.

• Lack of clear regulation for UCG project development.

These factors combined to effectively delay the international development of UCG technology for several years, although publication of the results of the demonstration (Walker et al., 2001; Blinderman and Jones, 2002) generated growing interest in the prospects of a revival of the technology in the Western world. This resulted from the size and longevity of the demonstration, its successful environmental outcomes, and the attractive cost estimates for producing power using combined cycle gas turbine systems (Walker et al., 2001). The Chinchilla experience also confirmed that commercial factors such as government regulation and project finance were likely to play a significant part in the rate of UCG development in Australia.

As a result of the experience at Chinchilla, the writer formed Cougar Energy early in 2006 and continued his association with Ergo Exergy to develop a new commercial power project using gas from a UCG facility as the fuel. The new company acquired rights to a coal lease near Kingaroy, also in Queensland, but modified its approach to commercial development by the following:

• Arranging for the company to be listed on the Australian stock exchange (ASX) in order to provide better access to capital.

• Developing longer-term plans for a phased 400 MW power project to achieve economies of scale to improve investment attractiveness.

• Designing a small gas treatment plant to demonstrate that the process would produce clean gas suitable for combustion in a gas turbine.

• Confirming that coal at Kingaroy could not be used for competing CSG production.

Following resource definition and site characterization work, development of the Kingaroy project was planned in the following stages:

• Ignition and syngas production, gas cleaning, and flaring for a period of 6–12 months.

• Power generation by gas engines or gas turbine up to 30 MW.

• Expansion of power generation to 200 MW, then 400 MW.

This phased program was not greatly different from that contemplated for the Chinchilla site; however, it was more clearly defined at an early stage in Cougar Energy's life, and with the technical experience gained from the past demonstration and the availability of progressive funding from the ASX listing, it was considered to be realistic.

15.3 Site characterisation

15.3.1 Resource definition and site selection

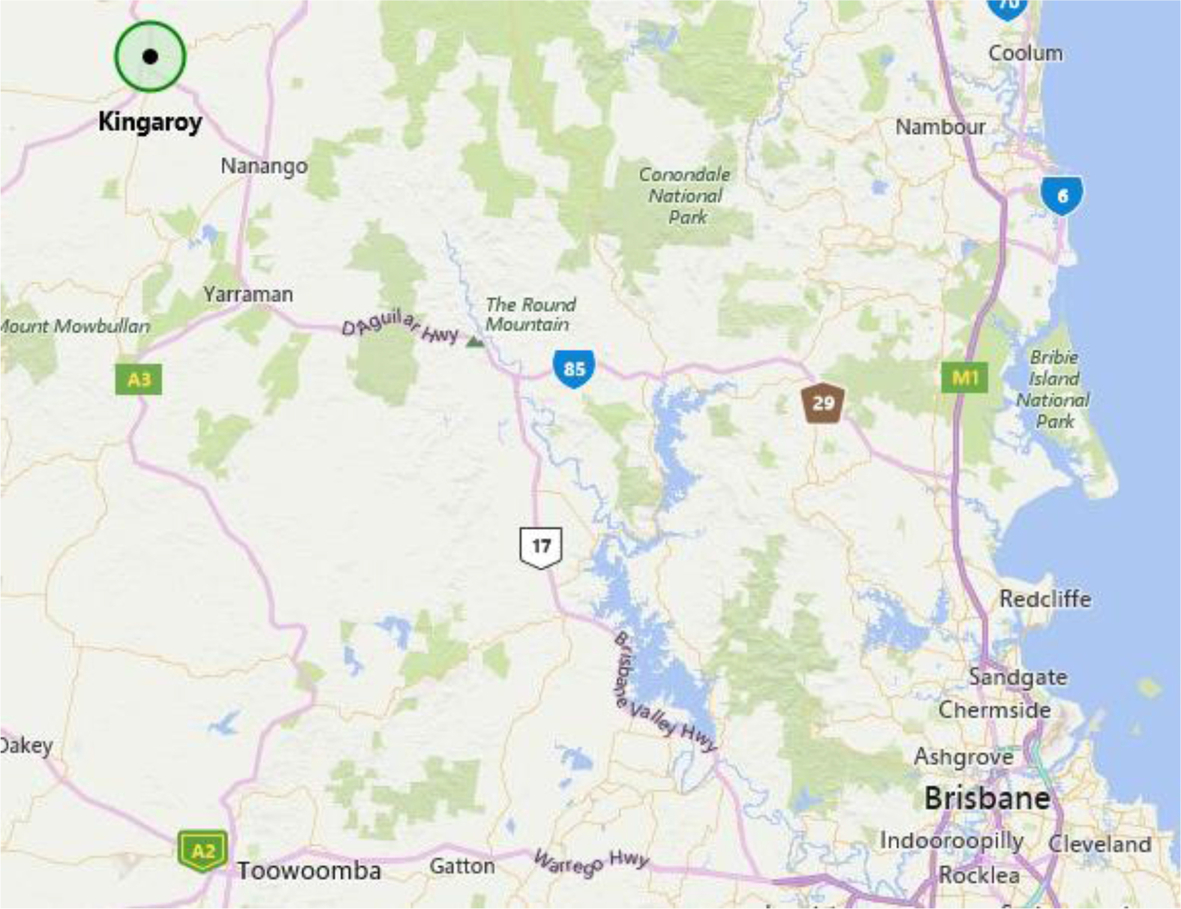

The location of the Kingaroy project (shown as MDL 385 on Figs. 15.2 and 15.3) was some 10 km south of the town of Kingaroy in Queensland, being part of a larger coal exploration permit (EPC882). The area was selected on the basis of a number of historical drill holes showing good coal intersections at depth.

A new exploration drilling program at Kingaroy was undertaken by Cougar Energy over the period late 2007/early 2008. Twenty-three holes were drilled with a total length of 4933 m, with 336 m of coring being undertaken, predominantly in the coal seams. Two main seams were identified, being the Kunioon and Goodger seams, separated by an interburden generally in the range 30–100 m. The Kunioon seam ranged in thickness from 7 to 17 m, at depths from 60 to 206 m, while the Goodger seam thickness ranged from 3 to 13 m at depths from 160 to 270 m.

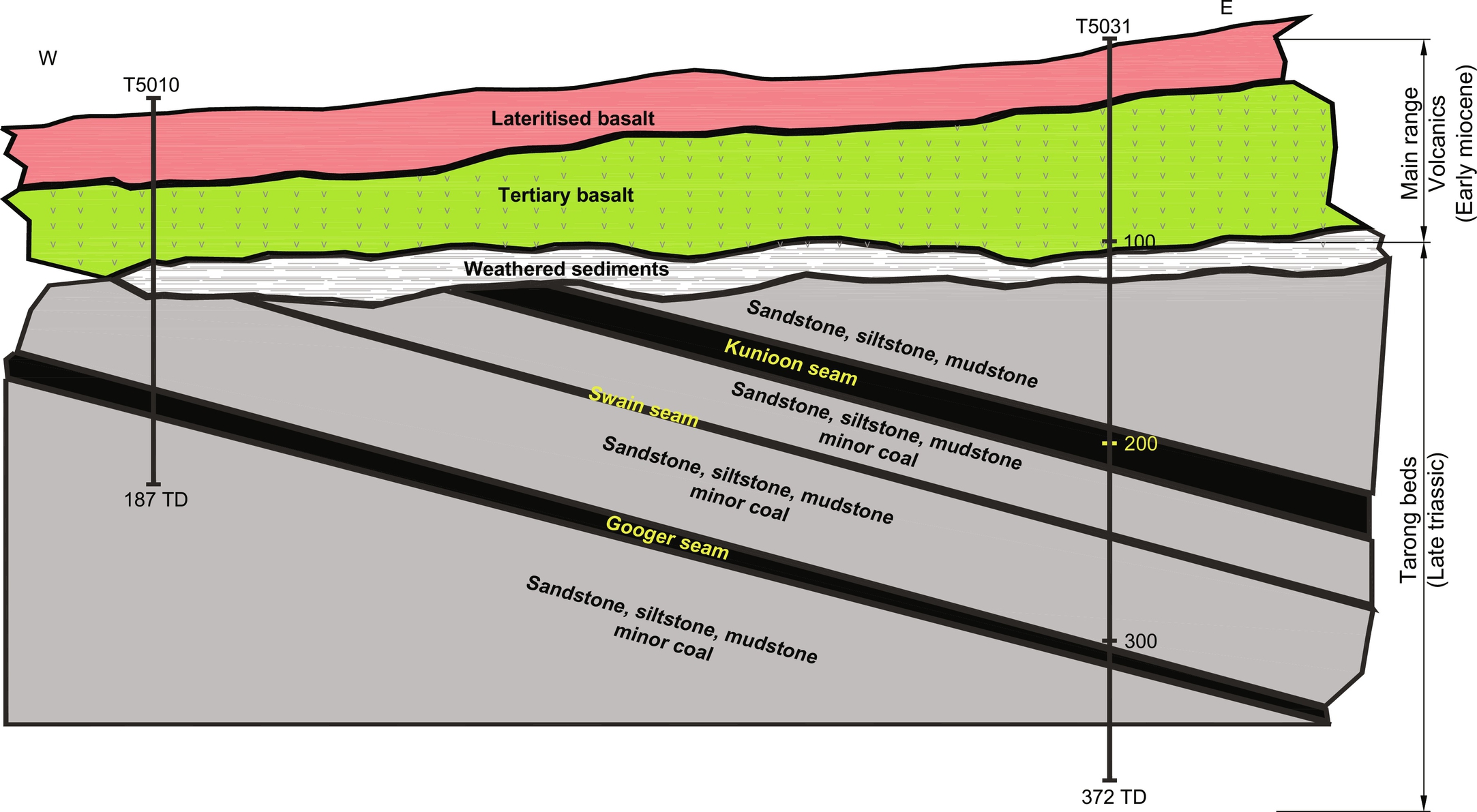

A typical geologic profile is presented in Fig. 15.4, which shows the Tarong coal beds lying beneath Tertiary basalt flows and the two main seams (Kunioon and Goodger) interbedded within sedimentary rock layers.

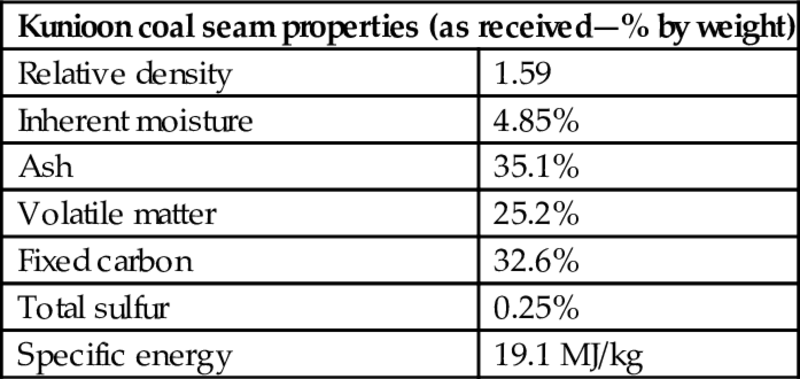

In July 2008, the company completed a JORC resource statement, resulting in indicated and inferred coal resources of 45 and 28 million metric tonnes, respectively, with approximately 70% of the resource being in the Kunioon seam. This resource size was considered to be sufficient to provide syngas to fuel the proposed 400 MW power station for 30 years. The average properties of the Kunioon coal seam are summarized below.

| Kunioon coal seam properties (as received—% by weight) | |

| Relative density | 1.59 |

| Inherent moisture | 4.85% |

| Ash | 35.1% |

| Volatile matter | 25.2% |

| Fixed carbon | 32.6% |

| Total sulfur | 0.25% |

| Specific energy | 19.1 MJ/kg |

Following a detailed evaluation of the drilling data, Cougar Energy selected the initial location for UCG development in the southeast corner of the exploration permit, largely because of its greater distance from local residents and a greater depth to the coal seam resulting from increased elevation in the area.

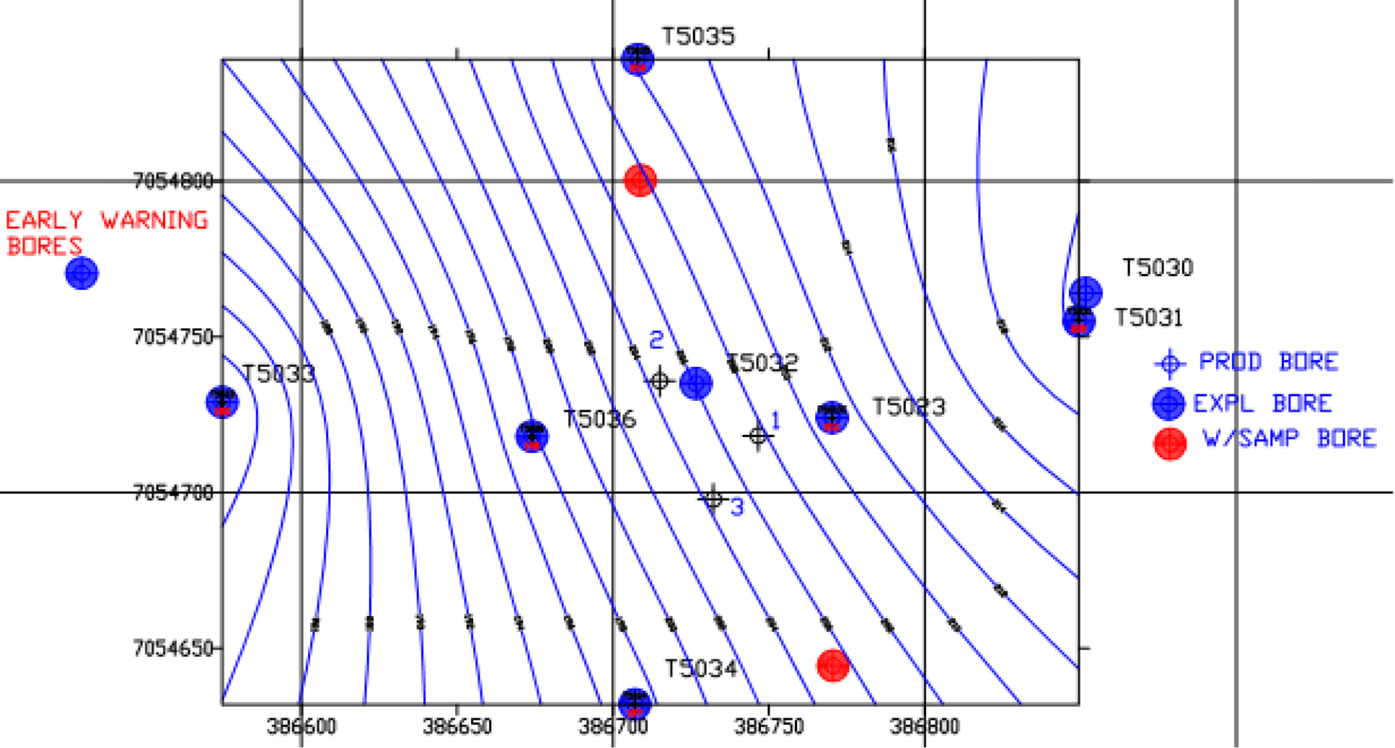

Fig. 15.5 shows the location of holes drilled in the ignition site area, together with water sampling and early warning bores. The locations of the first three injection/production wells (numbered 1, 2, and 3) are also shown in the figure.

Across the ignition area, the top of the Kunioon coal seam varies from 185 to 200 m below ground level. While the seam thickness over the area is generally around 15 m, there are a number of consistent partings within the seam that could potentially enable a thinner coal section to be utilized, to protect against potential overburden cracking allowing transmission of gas to the surface during larger-scale operations.

15.3.2 Hydrogeology studies

As part of the early evaluation of the Kingaroy UCG site, Cougar Energy undertook a desktop study of regional hydrogeology in April 2007. The study provided a broad appreciation of the geologic profile, regional groundwater conditions, like groundwater chemistry and potential direction of regional groundwater flow.

Following confirmation from resource drilling completed in early 2008 that

• A significant coal resource existed suitable for application of the UCG process.

• No major aquifer systems were evident in the geologic profile.

• A preferred site for initiation of the first phase of the project could be identified.

A detailed hydrogeological investigation program was initiated late in 2008 in accordance with the consent conditions for the project agreed with the Queensland Department of Environment and Resource Management (DERM) and contained in an environmental authority (EA) issued by DERM in April 2008. The conditions included the requirement for an independent hydrogeological report, which was subsequently undertaken and completed in March 2010 after a program of field and office work.

The program of hydrogeological work undertaken for the area in the vicinity of the proposed pilot burn site included

• Collation and review of all existing drilling and groundwater data.

• Preparation of geologic cross sections and a 3D geologic model.

• Packer testing of selected test sections within exploration boreholes to derive hydraulic parameters for specific rock/coal layers within the profile.

• Installation of six water quality monitoring bores around the proposed ignition area.

• A network of 23 vibrating wire piezometers (VWPs) installed as part of the test pumping of the Kunioon coal seam and also subsequently used during the air acceptance testing program. These were contained in five boreholes located around the pump test well.

• Test pumping from a purpose constructed well to capture the hydraulic response of a large area of the local groundwater system under groundwater extraction conditions.

• Air acceptance testing to test the response of the Kunioon coal seam to air injection.

• A groundwater model constructed to allow evaluation of response to conditions imposed during the UCG process, for example, groundwater consumption in the underground cavity.

• A baseline program for water quality monitoring, initiated in December 2009.

15.3.3 Hydrogeological profile

The hydrogeology of the Kingaroy test site is defined by the main geologic layers in the profile shown in Fig. 15.4:

• The Tertiary volcanic layer of low groundwater yield, consisting of multiple lava flows with interbedded sediment layers, and a basal contact layer with the Tarong beds consisting of montmorillonitic clay of low permeability. This basal clay layer was described as having a prime characteristic of “tight, squeezing clay behavior and an expansive nature,” which caused significant drilling problems and made it difficult to penetrate using typical drilling techniques.

• The Triassic Tarong beds, consisting of sandstone and conglomerate layers with very low groundwater yield and containing the coal seams of higher yield. Within the Tarong beds, detailed analysis of data from the pump testing indicated permeabilities ranging between 5 and 10 × 10− 6 m/s for the Kunioon coal seam and 3 × 10− 6 m/s for the overburden to the coal seam.

With respect to hydrogeology, the volcanic layer was determined to be spatially discontinuous as evidenced by dry conditions observed in several monitoring wells and the highly variable recovery rates observed during well installation and development. This was assessed as being a result of the size, persistence, infilling, and orientation of the relatively isolated pockets of water-bearing fractures in the rock structure.

The suite of groundwater measurements indicated a significant downward gradient from the volcanic layers to the Tarong beds, maintained by the relatively impermeable intermediate clay layer below the basalt. With respect to horizontal groundwater flow, the Kunioon coal seam dipped to the south, and this was interpreted as the groundwater flow direction in the seam, whereas groundwater measurements in the volcanic layers indicated a flow direction to the west.

The following relative hydrochemical features of the three hydrogeological units beneath the UCG pilot site were determined:

• Lateritic clay—High in Cu and Ni, low in bicarbonate (generally < 50 mg/L), slightly acidic (pH generally 5.5–6.5), brackish (TDS generally 1500–2500 mg/L).

• Basalt—Low in Cu and Ni, high in bicarbonate (generally 700–750 mg/L), slightly to highly alkaline (pH generally 7.3–11), brackish (TDS 1500–2000 mg/L).

• Kunioon coal—Low in Cu and Ni, moderate bicarbonate (generally 150–300 mg/L), slightly alkaline (pH generally 7–8.5), fresh (TDS generally 500–1000 mg/L).

Thus, the lateritic clay is distinguished from the other units by relatively elevated Cu and Ni concentrations, lower pH, and low bicarbonate. The basalt aquifer is characterized by relatively high bicarbonate and higher pH. The Kunioon coal aquifer is characterized by lower salinity (TDS and EC). The observed differences in the geochemistry suggest a reasonable degree of hydraulic separation of the hydrogeological units.

15.3.4 Hydrogeological impacts on Kingaroy pilot burn

The hydrogeological study provided evidence that the pilot burn could be undertaken with no significant impact on the groundwater system likely to occur. Factors supporting this conclusion can be summarized as follows:

• The Kunioon coal seam exhibits a permeability 2–3 times higher than its overburden.

• A relatively impermeable clay layer beneath the basalt provides a good aquitard to groundwater flow.

• There are no significant permeable aquifers above the coal seam in the geologic profile.

• Water quality in overburden layers is brackish and unsuitable as drinking water.

The pilot burn itself was limited in size to the gasification of a maximum of 20,000 tonnes of coal under the EA issued by the Queensland Government. With this limit, there was no concern about the possibility of subsidence occurring in a manner that might induce overburden cracking to reach the ground surface and potentially release chemical by-products into near-surface groundwater layers.

However, the thickness of the Kunioon coal seam (up to 17 m) was such that a detailed future evaluation would be necessary in relation to the interaction between cavity size and the depth and thickness of coal to ensure that this concern was fully addressed for the proposed commercial scale plant.

15.4 Government and community interaction

15.4.1 Government permits and approvals

In order to commence preparations for initiation of the first phase of its UCG project, Cougar Energy required approvals to advance the regulatory status of the relevant part of its exploration permit. The procedure applicable at the time in Queensland involved the following steps:

• Application for a MDL to permit small-scale noncommercial gas production to commence. Application for the MDL was made in December 2007, and it was eventually granted on 22 February 2009.

• During this period, Cougar Energy negotiated an EA that was issued by DERM in April 2008.

• Once the MDL was granted, a further application was required to enable the MDL to be utilized for UCG operations, the so-called “mineral (f)” classification under a clause (section 6 (2) (f)) in the Mineral Resources Act of 1989. The mineral (f) application was made in March 2009 and was granted in August 2009.

• Further expansion of gas production would require a mining license to be applied for and granted, with additional approvals required to allow power generation.

With a suitable coal resource being defined at Kingaroy late in 2007 and the MDL application being made in December 2007, it thus took a further 20 months for approval of the first stage of gas production to be achieved.

15.4.2 Government policy

A matter of considerable significance occurred on 18 February 2009 (4 days before the grant of Cougar Energy's MDL after a 14-month wait from the date of application). On that day, the Queensland Government released an Underground Coal Gasification Policy Paper (Queensland Government, 2009), which stated that “the Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy, if asked to determine a coordination or preference decision between the developer of a CSG resource and the developer of a UCG resource, the decision will be made in favour of the CSG tenure holder under the P&G Act, so as to allow the CSG tenure to progress to production stage.” The impact of this policy was amplified by the fact that, at that time, virtually all coal basins in Queensland were covered by CSG (coal seam gas) tenure.

This Policy Paper also confirmed that the government would review the progress of UCG projects, with a decision on the future of UCG in Queensland to be determined in 2011–12. Earlier, in August 2008, press reports had circulated claiming that the “government had no intention of granting production tenures for UCG for at least 3 years.” While there was some question of the accuracy of these reports at the time, the Policy Paper effectively achieved the same outcome.

The Policy Paper also provided for the establishment of a “scientific expert panel” to assist the government in preparing a report on UCG technology for consideration by Cabinet. The Policy Paper concluded that “…should the government report produce adverse findings on the UCG technology, on-going constraint, or even prohibition of UCG activities may be recommended.” Regrettably, when the panel was formed, its members had no previous experience in UCG technology and no international representation and gave little regard to the success of numerous demonstrations overseas and, more specifically, the success of the Chinchilla test 10 years earlier.

It is noted that the Policy Paper was issued at a time when Cougar Energy had completed its resource evaluation process, had negotiated an EA, and had made significant progress on its hydrogeological testing program and pilot plant design. It was only after some internal consideration that the company elected to continue with its proposed project despite the newly created regulatory uncertainty.

15.4.3 Community relations

The Chinchilla test burn initiated in late 1999 was undertaken with the support of the Queensland Government at its operating level in the relevant departments and the support of the landowner on whose property the test was undertaken—less than 500 m from his house.

During preparations for initiation of the Kingaroy project, Cougar Energy undertook a program of community relations, involving meetings with those landholders within the proposed area of development, and a project presentation evening for local residents. In October 2009, after the commencement of site preparation for construction of the pilot burn, an open day was held for all residents to explain the proposed development sequence.

However, it became progressively evident that the level of support at Chinchilla could not be reproduced at the Kingaroy site because of the following:

• The increasing political influence on the government of the CSG industry, which was in its infancy in 1999.

• The resultant change instance of the state government to the UCG industry, as expressed in its 2009 UCG policy, by raising issues as to whether the technology would be “acceptable” in Queensland.

• The development of a local group protesting against the technology and its impact on the local state political representative.

While each item appeared to the company to be manageable at that time, circumstances following ignition conspired to bring them together in a manner that ultimately led to the termination of the project, as described in later sections.

15.5 Preparations for ignition

Following completion of the resource evaluation, the site selection, and the receipt of the EA in April 2008, Cougar Energy commenced detailed design of the UCG pilot plant facility. This was undertaken to meet objectives required to support later expansion to the commercial facility, which included

• Sufficient syngas production and processing capacity to produce a power output of up to 30 MW.

• Gas processing plant capable of producing a cleaned syngas suitable for meeting gas turbine specifications.

• Site layout (both gas production and gas processing plants) capable of being expanded in modular form to increase output.

• Preliminary feasibility study for the medium-term design case of a nominal 200 MW syngas/power generation project.

The company had undertaken some preliminary treatment plant design work early in 2008 and in May 2008 appointed consulting engineers to undertake detailed design for the pilot plant project as a whole. This work was completed late that year, by which time construction of long lead-time items of plant had commenced, with contract packages for all other work being assembled in January 2009.

All of this work was undertaken in expectation of an imminent grant of the MDL (applied for in December 2007), which was ultimately granted in February 2009, but only after release of the Queensland Government's UCG policy with its associated uncertainties. After the company made a considered decision to proceed with the project, the contract packages were put out to tender, with the company now awaiting grant of the “mineral (f)” attachment to the existing MDL. This was received late in August 2009, and the successful contractor was appointed a few days later. By this time, the first three UCG production wells had been installed and tested, with commissioning of the plant being scheduled for February 2010.

During the latter half of 2009, design staff were appointed in the company's Brisbane office to undertake the preliminary feasibility study for a nominal 200 MW UCG/power plant, with the majority of this work being completed by mid-2010 with favorable economic results. Thus, by early 2010, Cougar Energy had largely completed its objectives for pilot plant design and construction and for the large-scale project feasibility analysis.

15.6 Syngas production, cessation and the events leading to project shutdown

15.6.1 Gas production operations

The first three production wells (P1–P3) at the Kingaroy site were installed in April/May 2009 at locations shown in Fig. 15.5. A fourth well (P4) was installed in October 2009 placed to give a minimal connection distance to P1 for starting the UCG process.

Ignition was achieved in the afternoon of 15 March 2010, and gas production developed using the reverse combustion linking process, which was completed by the evening of 17 March. At that time, compressed air was being injected into well P1, with syngas produced from well P4.

The underground gasifier operating conditions were monitored indirectly and continuously. All wells were equipped with flow, temperature, and pressure measurement instruments on the pipe leading into the ground. The dry gas composition was measured using a gas chromatograph, with water and heavy hydrocarbons removed from the gas prior to measurement.

The groundwater pressure at a number of locations and in a number of geologic layers was measured using the 23 installed VWPs. During forward gasification and reverse combustion linking, these data were required to ensure that the pressure in the cavity was kept lower than the local groundwater pressure to ensure flow of water was maintained toward the cavity.

Gas production from P4 continued until the morning of 20 March (113 h in Fig. 15.6), when it ceased, indicating blockages in both P1 and P4, at which time air injection was stopped, and the surface pipework at P4 was dismantled and blockages removed. Air injection into P4 was then continued for some 3 weeks, until 9 April, when a groundwater sampling well (T5037) located some 250 m from P4 was observed to be bubbling air and water to surface. Air injection into P4 was immediately ceased and a review of all information made.

A detailed investigation of well P4 followed, including the use of a downhole camera, which established that at 62.5 m depth in the well, the coupling between casing strings had separated and the casing below this level had been deformed.

15.6.2 The casing string design

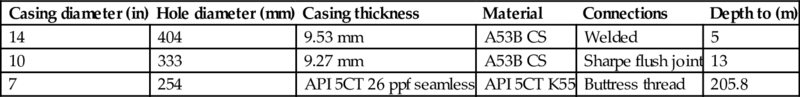

In the installation of P4, three strings of casing were utilized as outlined in Table 15.1. Each of the three casing strings was cemented into place. The 14 and 10 in strings were cemented in using a standard Portland cement mix with specific gravity 1.72, while the 7 in casing was cemented using a cement containing silica flour.

Table 15.1

Casing string design

| Casing diameter (in) | Hole diameter (mm) | Casing thickness | Material | Connections | Depth to (m) |

| 14 | 404 | 9.53 mm | A53B CS | Welded | 5 |

| 10 | 333 | 9.27 mm | A53B CS | Sharpe flush joint | 13 |

| 7 | 254 | API 5CT 26 ppf seamless | API 5CT K55 | Buttress thread | 205.8 |

The reason for using a multiple casing string design is related to the geologic conditions. Cougar Energy's geologists, in conjunction with various drillers that were engaged in the exploration drilling programs over the previous 2 years, had evaluated the best techniques for drilling holes down to the coal seams of interest. The main problems they encountered related to the expansive clay formations above and below the basalt. Experience showed that if these formations were not cased off (by using the first and second casing strings shown in Table 15.1), then the clays would expand and block the hole while drilling through them. The technique used for drilling these exploration holes was then translated across to installation of the production holes.

As it transpired, the use of multiple casings created complexities in cementing the casings into place. A detailed assessment of all possible failure mechanisms for well P4 concluded that residual water was left behind between the 7 and 10 in casings at a depth of about 63 m, which expanded on heating, causing the inner casing to collapse. As a result of this experience, two new wells were planned for installation (P5 and P6) using a larger rig and a single continuous casing. These wells were successfully installed, and operations were scheduled to recommence in late July 2010.

15.6.3 Events leading to shut-down notice

With evidence of the well casing failure in P4 and some groundwater response (bubbling of air) in monitoring bore T5037, Cougar Energy increased the frequency of monitoring bore water sampling and testing, specifically for the chemicals benzene and toluene. The monitoring focused on T5037, screened over the interval 35–47 m, and a nearby bore (T5038) 10 m away, screened over the interval 64–76 m, each about 250 m from the gasification zone.

Groundwater samples from T5037 exhibited benzene levels of 2 ppb (parts per billion) from samples taken on 11 and 27 May 2010 and 1 ppb (the laboratory limit of detection) from samples taken on 6 June and 16, with subsequent readings being below the level of detection. No toluene was measured in this bore. No benzene was measured in T5038, although toluene was measured at levels well below trigger levels. The difference in observations between these two sets of results led to some uncertainty in interpretation of the data.

In relation to trigger levels, the EA applicable to the Kingaroy pilot burn stated that

In the event that contaminant trigger levels (as identified in the groundwater monitoring program) are exceeded, or the groundwater monitoring program detects a likely material failure of the production water containment system, or migration of contaminants from the coal seam that is being or has been gasified, the authority holder shall promptly assess and report to the administering authority on potential environmental impacts investigation of the causes and remedial measures to be implemented.

Groundwater trigger levels for shallow monitoring bores had been recommended by Cougar Energy's groundwater consultants as being those applicable in the Australian water drinking limits, namely, 1 ppb (parts per billion) for benzene, and for deep monitoring bores those covered by the Australian and New Zealand guidelines for fresh and marine water quality (2000)—950 ppb for benzene. The World Health Organization recommendation for benzene in drinking water is 10 ppb.

After receipt of the initial data (some 10 days after sampling) and a subsequent review, the company prepared a report to DERM that was submitted on 10 June. The data were discussed with DERM officials at a meeting in late June, and it was concluded that no environmental threat was present, especially given that baseline quality of groundwater at the monitoring bores was not suitable for drinking. As a result, the company was allowed to continue with its earlier planned reignition of the coal seam scheduled for late July 2010. However, the company was requested to table any trigger level exceedances more rapidly than had been done on this occasion.

On 13 July 2010, Cougar Energy received from the testing laboratory a reading of 84 ppb purported to come from T5038, in which no previous measurement of benzene had been recorded. In providing these data rapidly to the government authorities, the company advised of the likelihood that it was an erroneous reading and supported this on 14 July 2010 with a further check test result from the same bore that showed no benzene at the level of detection (Cougar Energy, 2011a).

On 16 July, Cougar Energy forwarded to DERM a letter from the independent testing laboratory confirming that the reading was the result of a mix-up of samples and that the correct sample recorded no detectable benzene. This result was confirmed by DERM's own sample test results; however, on 17 July 2010, DERM issued a shutdown notice on the site. Evidence (Cougar Energy, 2011b) suggests that this was a result of pressure from a number of local residents expressed through their local member of parliament. No subsequent readings of benzene above the detection limit were recorded at the site despite widespread monitoring over the following years; however, the shutdown order was confirmed and enforced.

15.7 Environmental issues

15.7.1 The environmental evaluation process

The shutdown notice triggered off a lengthy process involving the preparation by Cougar Energy of reports requested by DERM using its powers under the Environment Act. These reports were prepared in response to a series of questions raised by DERM following the service of the shutdown notice. The reports covered topics such as operations prior to the well blockage, analysis of the casing failure, and interpretation of the groundwater mechanisms involved in the transport of chemicals. In the period August to December 2010, 16 separate environmental evaluation reports were submitted to the government, containing more than 650 pages of detailed data and analysis.

During this period, DERM had also requested the independent select panel (ISP) to review the performance of Cougar Energy on the Kingaroy project. This panel had been set up by the government in October 2009 and was given the task of reviewing all current UCG projects in Queensland and making recommendations on the future of the technology in that state. In January 2011, the ISP produced a public report with criticisms of much of Cougar Energy's work.

The company responded in February with a public critique of this report (Cougar Energy, 2011b), recording errors of fact, disputing many of its findings, and providing evidence that it may have been prepared without reference to the voluminous reports submitted by the company in the previous year. As an example, the ISP report stated that “It is unclear why the trial was not located in a more simple hydrogeological setting, which was available not too distant from the existing site.” No evidence or technical discussion was given to support this conclusion.

Ultimately, in early July 2011, DERM notified the company of its decision to amend the company's existing EA to prevent it from restarting UCG gas production on the site and restricting activity to rehabilitation and monitoring.

Despite the acceptance by all parties that the limited and localized (in time and space) benzene levels reported in no way caused any environmental harm, the government in July 2011 issued charges under the Environment Act relating to failure of the production well, the evidence of benzene and toluene in monitoring wells, and a claimed delay in reporting these readings. The company responded in October 2011 by issuing proceedings against the government and its officials in the Supreme Court of Queensland claiming A$34 million in damages. As events transpired, the Supreme Court proceedings were eventually discontinued by agreement between the parties in July 2013.

At that time, it was clear that the future development of UCG in Queensland, and certainly Cougar Energy's potential role in such development, had little chance of advancing for the foreseeable future. As it transpired, the government in April 2016 announced a permanent ban on UCG technology in the state.

15.7.2 The environmental authority

At the time of preparation of the EA by the Queensland Government, the task was undertaken by the relevant regional office in Maryborough, 250 km north of Brisbane, the state capital. Cougar Energy management met with environmental staff in their office to discuss UCG technology and the proposed project development schedule, commencing with the pilot burn phase. The resulting EA was tabled in April 2008 and restricted the test to the gasification of no more than 20,000 tonne of coal. Subsequent events underscored significant deficiencies in the EA and its wording that played a part in the eventual termination of the Kingaroy project.

The introductory clauses in the EA carry the following wording:

In carrying out the activities to which this approval relates, you must take all reasonable and practicable measures to prevent and/or minimise the likelihood of environmental harm being caused.

This clause and its use of the term “likelihood of environmental harm” provided the opportunity for a range of possible interpretations as to its meaning. The general nature of the term was exacerbated by the reference to the term “trigger levels” in the EA as described in Section 15.6.2 and the actions required if they were exceeded. No trigger levels were defined in the EA, and both the company and MEMR relied on the general recommendations contained in the company's hydrogeological report, viz.

For “shallow on-site monitoring bores: Drinking Water Criteria (ANZECC 2000)” and

For “Deep on- and off-site monitoring bores: Protection of Aquatic Ecosystems at 95% level of protection”

These general recommendations were not translated into trigger levels for specific chemicals nor related to the location and depth of specific monitoring bores and the possible use of water in any monitored aquifer systems. It is evident from the events that occurred in the Kingaroy project with respect to the benzene level readings that the company and DERM had quite different interpretations of the actions necessary with respect to using the trigger levels to meet the requirements of the EA, with significant technical and financial consequences.

15.8 Rehabilitation and monitoring

Under the revised EA, Cougar Energy was required to rehabilitate the UCG site, involving both surface plant and groundwater conditions. This work involved conventional activities such as plugging of production wells, removal of pipework, decommissioning and removal of the gas treatment plant, and cleaning and backfilling of the water storage dams. It was completed by mid-2015.

Rehabilitation of the groundwater in the vicinity of the gasification area proved rather more complex, largely because no clearly defined requirement for residual chemical compositions for benzene and toluene was defined in the EA. The company had always argued that, as none of the layers in the geologic profile could be considered as an existing or potential aquifer for potable water, the Australian drinking water standards (1 ppb for benzene) should not apply as a residual level, but rather the guidelines for fresh and marine water quality (950 ppb for benzene). It is understood that this issue is yet to be resolved.

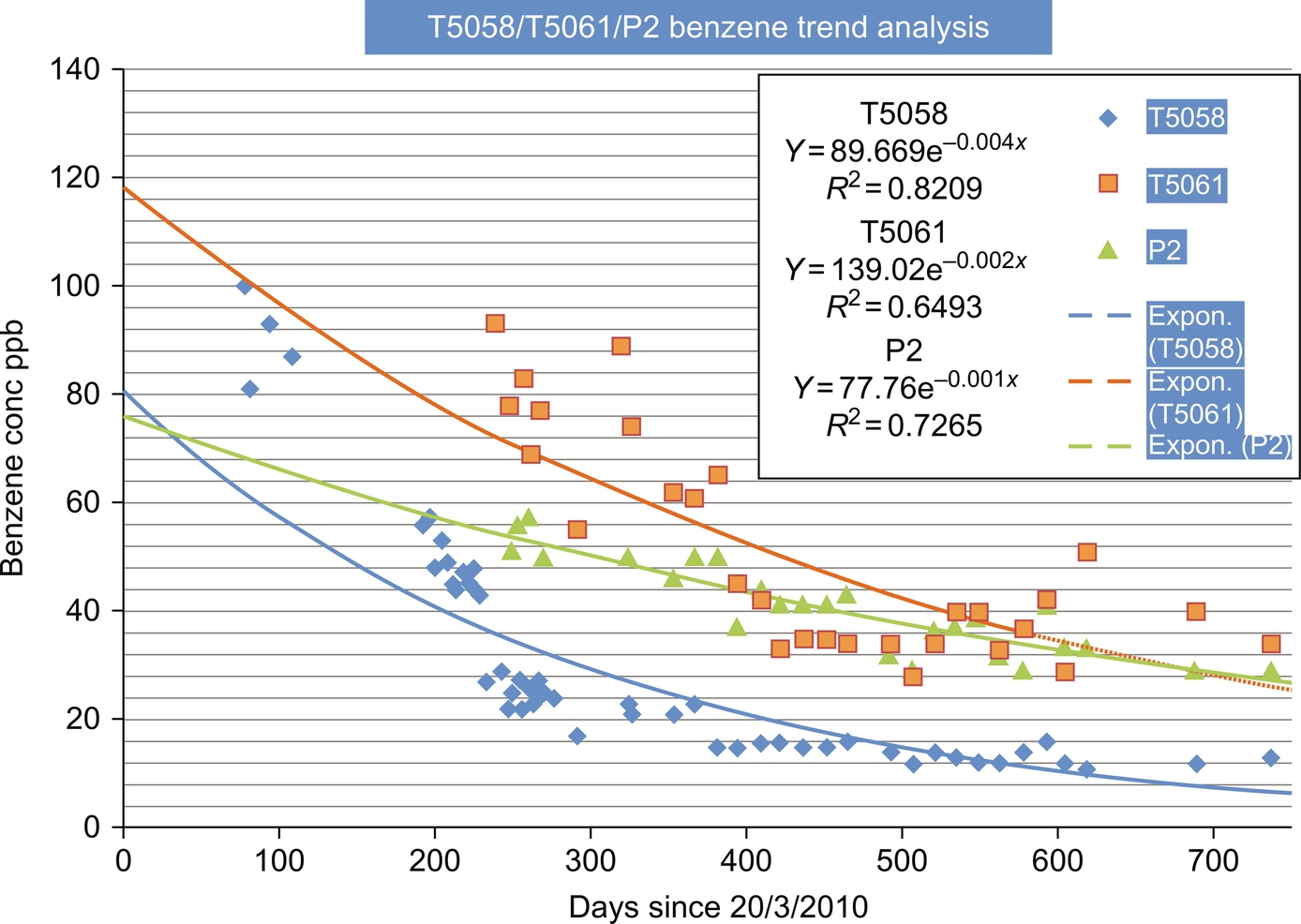

Cougar Energy had previously installed three groundwater monitoring bores in the coal seam relatively close (4–10 m) to the gasification zone. It was in one of these bores that the reading of 84 ppb was obtained, which was erroneously attributed by the testing laboratory to T5038 some 250 m away and which led to DERM's actions in issuing the shutdown notice. Monitoring of benzene levels in these bores continued from shutdown in July 2010 to the present (December 2015), when the highest level was 2 ppb.

In relation to potential decay of benzene levels in coal, Cougar Energy had undertaken a study to establish the principles of monitored natural attenuation whereby benzene levels attenuate over time naturally as they are degraded by microbial activity. The success of this procedure at Kingaroy is illustrated in Fig. 15.7, which shows the benzene decay curves over time for the three wells closest to the gasification zone. Each of these curves is realistically represented by a logarithmic decay curve, as might be expected from theoretical considerations. As is evident from the curves, once the benzene level is below 10 ppb, further reductions are extended in time. However, given that the World Health Organization's drinking water limit is set at 10 ppb and it is unlikely that any coal seams would double as potable aquifers, reductions in benzene concentration below this level would have no practical environmental significance.

15.9 Conclusions from the Kingaroy UCG project

15.9.1 General

The initial concept for the Kingaroy project involved the phased construction of a 400 MW power project, starting with an initial phase of about 2–5 MW equivalent of gas production prior to installation of the power plant. The concept, initiated in late 2006, was supported technically by the long gas production experience of Cougar Energy management on the Chinchilla project and financially by the economic analysis contained in the Cougar Energy preliminary feasibility study. Subsequent analyses have confirmed this view (Walker, 2014). In the early stages of the Kingaroy project development, there appeared to be strong support from the Queensland Government to see the project develop.

The outcome was gas production lasting only 5 days, gasifying an estimated 20 tonne of coal, before the production well blockage and failure on 20 March 2010, and the subsequent events involving two measurements of benzene in one monitoring well at a level of 2 ppb, barely above the level of detection of 1 ppb. While these readings were considered by the government at the time to be of no concern, a subsequent erroneous reading 1 month later (due to a laboratory sampling mix-up) was used by the government as a justification for shutting down the site, despite a lengthy period of report preparation by the company assessing the well failure and describing measures taken to prevent a recurrence.

As a result, Cougar Energy wrote off some A$20 million of direct expenditure on the project, apart from associated additional head office expenditure. Commercial development of the technology in Queensland at that time was thus no further advanced than it was at the time of the first test at Chinchilla 15 years earlier, despite the expenditure of substantial funds by Cougar Energy and the two other UCG companies active in the state, together investing a total estimated at more than A$300 million. Conclusions to be drawn from the Kingaroy project can best be considered under the separate headings of technical and regulatory issues.

15.9.2 Technical issues

There are two technical issues flowing from the Kingaroy project that can be identified as impacting on the successful achievement of its original goals—the failure of the casing in production well P4 and the lack of preparation and acceptance by government of a detailed plan covering monitoring, reporting, and remedial actions associated with potential groundwater contamination.

While the “triple casing” design was justified by the experience from previous drilling campaigns, its use for the production wells introduced greater complexity in the installation and cementing procedures. While these issues could have been eventually overcome, they resulted in high water pressure developing behind the casing in well P4 that contributed to its collapse. The system used for wells P5 and P6, installed but not utilized, confirmed the advantages of a simpler design. The experience reinforces the care required in selecting a casing system that is best adapted to both the geologic conditions encountered and the requirements of achieving successful in-place grouting.

Of greater significance to the project, however, were the implications associated with groundwater monitoring and the interpretation of the data obtained. The lack of clearly defined and agreed groundwater guidelines between the company and the regulatory agency allowed widely different interpretations of the recovered data to be made, despite the fact that all parties agreed that no threat of environmental harm existed at the site.

A practical groundwater protocol that should have avoided the complications resulting from the use of the Kingaroy groundwater data could have consisted of

• The definition of an operating gasification zone around the immediate cavity, within which high concentrations in groundwater would result from the chemical processes occurring during operations.

• Around this gasification zone, definition of an inner (monitoring) and outer (compliance) ring of groundwater monitoring bores each with their own trigger levels for water quality.

• Definition of responses required in each case of trigger level being exceeded, including alternatives involving repeat measurements to establish trends, remedial actions, or ultimately operational shutdown.

• Acceptance of groundwater standards for acceptable long-term levels of relevant chemical compounds (e.g., WHO, ANZ guidelines for fresh and marine water quality).

A schematic interpretation of the above requirements is shown in Fig. 15.8, with the specifics dependent on local site conditions.

For the specific case of benzene, the starting point for assessing the significance of acceptable permanent levels is the classification/zoning of any overlying water resource or aquifer. Where the water resource is used for human consumption, reference should be made to the level acceptable for drinking water. This level is measured in micrograms/liter or parts per billion (ppb). Different countries have different standards required for drinking water with the WHO adopting a figure of 10 ppb. This standard is based on an assessment that a human, drinking 2 L of water a day for 70 years, will have a 1 in 100,000 extra chance of developing cancer (World Health Organisation, 2011).

Assessing an acceptable permanent level for benzene in a coal seam that is impacted by the UCG process, but is not classified as a water abstraction aquifer, is a more difficult exercise. The reference commonly used is the “Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality” (Australian Government, 2000). Under these guidelines, recommended trigger levels for benzene at the 95% level of species protection are 950 ppb (freshwater) and 700 ppb (marine water).

With the acceptable levels of benzene in groundwater potentially varying from 10 to 950 ppb, it is evident that each specific UCG location requires individual consideration in the selection of a relevant benzene trigger level. Factors of relevance include the following:

• Whether the water is in the coal seam or overburden. If in the coal seam, natural decay of levels of benzene with time after completion of operations is likely.

• Whether the water is being used for drinking or is likely to be used for drinking, in the period of process operations or in the longer term.

• The regional groundwater hydrological system. If contaminants do escape, data are required to show where they will be carried and how rapidly and whether dilution will occur.

• What is the level of any observed contaminant in relation to the approved trigger level?

• If contaminants are observed, how will they be treated and over what time period?

An installed monitoring system such as illustrated in Fig. 15.8, combined with a reporting and action response plan, will give the regulatory authorities the mechanism to enforce the agreed environmental management plan and should form the basis for an open and transparent integration of all stakeholders in the compliance reporting process.

15.9.3 Issues of regulatory control

A major issue in the acceptance of the UCG technology by the regulators in any country is the extent to which they are prepared to accept the experience gained elsewhere in developing the technology. Although this past experience is largely at a demonstration level, the range of data available from tests in a number of countries can be utilized to allow acceptance of the value of the technology and enable the development of a regulatory regime for a commercial project. This would avoid the necessity for the regulatory approach of “reinventing the wheel” by demanding a further demonstration project prior to acceptance of potential commercial development, with the financial risks that this entails for the developer, as was well illustrated by the Queensland experience.

The Chinchilla demonstration of 1999–2004 was undertaken in a cooperative spirit between government and developing company, with regular environmental reporting being utilized to ensure that no environmental threat existed. For the Kingaroy project, a change in government attitude to the technology occurred late in 2008 after various financial commitments by a number of UCG companies had been made, presumably as a result of political factors that can only be inferred from evidence available, including

• The declared preference for CSG technology wherever conflicts with UCG occur (February 2009).

• The predominance at the time of CSG tenement applications over all coal basins in Queensland.

• The delay in granting approval of the MDL required for the first Kingaroy phase (22 months).

• The establishment of a scientific panel to review all aspects of UCG technology to assess whether it should be permitted in Queensland (October 2009), despite its proved success in development internationally.

• The lack of consistency between the technical arm of the Queensland Government that accepted the negligible and short-lived benzene readings and the political arm, which initiated the shutdown on an erroneous report of one high benzene reading.

Regrettably for each of the UCG project developers in Queensland, who (from 1999 onward) had commenced developing their projects in good faith and with the support of officers in the relevant Queensland government departments, the political arm of government chose (early in 2009) to introduce a major uncertainty as to the future of the UCG industry in the state. The technical and financial impacts on each of the developers have been significant, more especially because of the government's decision in April 2016 to ban the technology in the state.

15.9.4 Summary of conclusions

The lessons that arise from the Kingaroy project relate more to the establishment of practical government regulations rather than specific technical issues about the UCG process itself. These might be summarized as follows:

• Some well failures might be expected as for any other drilling-related activity. Provided adequate site, health, safety, and environmental controls are in place, these should be accepted by the regulator as in other industries.

• In relation to groundwater issues, environmental regulations require definition of operating project areas within which temporarily acceptable contaminant levels are defined, as exists for conventional mining/chemical projects.

• Regulations should also provide a precise definition of site-specific trigger and rehabilitation levels for potential contaminants in groundwater, which take into account the relevant chemical and its measurement location, the groundwater end use, and the period of time by which rehabilitation will be required.

• Development of coal using the UCG process should be clearly defined in relevant legislation in a way that permits development as for other mining-related projects, with appropriate support from government for UCG companies working with local communities.

In addition to the above factors, education of government regulatory staff in the UCG process, using the vast amount of data available in the public domain, is an integral part of ensuring a minimum of difficulty in resolving the many operating issues likely to arise from commercial development of UCG technology in the future.