Using fire to remediate contaminated soils

J.L. Torero*; J.I. Gerhard†; L.L. Kinsman†; L. Yermán* * The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

† University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

Abstract

Remediation technology based on smoldering combustion is an innovative approach that has significant potential for sites contaminated with organic compounds. Many common industrial contaminants present in the soil are flammable. Combustion of an organic phase contained within a porous medium involves an exothermic reaction, during which heat is transmitted from the burning to the pore space and the solid matrix. Contaminant destruction in such applications is largely dominated by smoldering (as opposed to flaming) combustion. The results described in this paper indicate that smoldering remediation is viable across a considerable range of porous media types and subsurface conditions.

Keywords

Coal; Organic compounds; Smoldering combustion; NAPL; Soil remediation

18.1 Introduction

Tens of thousands of sites worldwide exhibit contamination of groundwater and surface water by historical and continuing accidental releases of hazardous nonaqueous-phase liquids (NAPLs). Common NAPLs include petroleum hydrocarbons (oils and fuels), polychlorinated biphenyls (electric transformer oils), chlorinated ethenes (solvents and degreasers), creosote (wood treaters), and coal tar (manufactured gas plants). Complex and/or long-chain compounds, such as heavy oils, PCB oils and coal tar, are particularly recalcitrant, resisting degradation via physical (e.g., volatilization), biological (e.g., dehalogenation), and chemical (e.g., oxidation) treatments that are becoming accepted remedies for more amenable contaminants. Dealing with such wastes typically involves excavation and either disposal to a hazardous waste landfill or incineration at substantial cost. As an alternative, this research paper proposes a new approach—NAPL smoldering—as a potential remediation process.

The combustibility of NAPLs is a characteristic that has been successfully exploited through the ex situ incineration of NAPLs and contaminated soil (e.g., Howell et al., 1996). Incineration is primarily achieved via flaming combustion. Flaming combustion involves the gasification of a fuel and its exothermic oxidation in the gas phase. Incineration of NAPLs by flaming combustion is energy inefficient (i.e., high heat losses); as a result, incineration requires the continuous addition of energy.

Smoldering combustion, in contrast, is the gasification and exothermic oxidation of a condensed phase (i.e., solid or liquid) occurring on the fuel surface (Ohlemiller, 1985). Smoldering is limited by the rate of oxygen transport to the fuel's surface, resulting in a slower and lower temperature reaction than flaming. Importantly, smoldering can be self-sustaining (i.e., no energy input required after ignition) when the fuel is (or is embedded in) a porous medium. Self-sustaining smoldering occurs because the solid acts as an energy sink and then feeds that energy back into the unburnt fuel, creating a very energy-efficient reaction (Howell et al., 1996). Solid porous fuels such as polyurethane foam (Torero and Fernandez-Pello, 1996), cellulose (Ohlemiller, 1985), and charcoal are typical media that exhibit self-sustained smoldering. These studies have demonstrated that the rate of combustion front propagation, limits of self-sustained propagation, and net heat generation by the reaction are affected by the velocity (magnitude and direction) of air, pore diameter of the medium, and the fraction of porosity occupied by fuel, air, and nonreacting materials (DeSoete, 1966).

Smoldering reactions can leave a carbonaceous residue behind the reaction front (oxygen-limited reactions), or in some instances, they can result in complete combustion of the fuel (fuel limited) (Schult et al., 1995). The former is very common in reacting porous media (e.g., foam) where the insulating char minimizes heat losses and enables the reaction to propagate. The latter is common when the fuel is combined with an inert porous media (e.g., oil in silica sand) that provides the require insulation even in the absence of the fuel.

While smoldering of solid fuels has been the focus of most research, there are several examples of combustion where smoldering of a liquid fuel embedded in an inert or reacting porous matrix may be observed. Lagging fires occur inside porous insulating materials soaked in oils and other self-igniting liquids (Drysdale, 2011). To enhance oil recovery, combustion fronts are initiated in petroleum reservoirs purposely to drive oil toward an extraction point, a technique known for high energy efficiency (Greaves et al., 1993). The reactions involved in enhanced oil recovery through in situ combustion are described as heterogeneous gas-solid and gas-liquid between oxygen and the heavy oil residue (Sarathi, 1999).

NAPL smoldering would be different from existing thermal remediation techniques. In situ thermal treatment requires the continuous input of energy in order to primarily volatilize and, in some cases, thermally degrade (pyrolyze) and mobilize (via viscosity reductions) the organic phase. All of these processes are endothermic, and thus, remediation only continues as long as externally supplied energy input is sustained throughout the NAPL-occupied porous medium. In contrast, NAPL smoldering has the potential to create a combustion front that (i) initiates at a single location with the NAPL-occupied porous medium; (ii) initiates with a one-time, short-duration energy input; (iii) propagates through the NAPL-occupied medium in a self-sustained manner; and (iv) destroys the NAPL at a location as the front passes. NAPL smoldering would be different from in situ combustion for enhanced oil recovery in that the latter is designed so as to generate heat and gas pressure that will mobilize the entrapped oil toward recovery wells. NAPL smoldering, in contrast, may benefit from avoiding the recovery (and thus treatment) of NAPL and/or water.

18.2 Principles of smoldering

Smoldering is normally studied as a common fire initiation source. It appears in the form of cigarettes interacting with upholstered furniture, overheated wire insulation, spontaneous ignition of hay stacks or embers, etc. Smoldering is characterized by a slow exothermic reaction (propagation velocities are of the order of 0.1 mm/s) occurring at low temperatures (characteristic smolder temperatures are of the order of 400–800°C) and with almost unnoticeable smoke release.

Smoldering may occur in a variety of processes that range from smolder of porous insulating materials to underground coal combustion. Many materials can sustain smoldering, including wood, cloth, foams, tobacco and other dry organic materials, and charcoal. The ignition, propagation, transition to flaming, and extinction of the smolder reaction are controlled by complex, thermochemical mechanisms that are not well understood.

Smoldering combustion of porous materials has been studied both experimentally and theoretically. From a fundamental point of view, smoldering is a basic combustion problem that encompasses a number of processes, including heat and mass transfer in a porous media, endothermic pyrolysis of the fuel, ignition, propagation and extinction of heterogeneous exothermic reactions at the solid/gas pore interface, and onset of gas-phase reactions (flaming) from the existing surface reactions (Ohlemiller, 1985).

From a practical point of view, smoldering has been discussed as a risk because the combustion can propagate slowly in the material interior and go undetected for long periods of time. It typically yields a substantially higher conversion of fuel to toxic compounds than does flaming (though more slowly) and may undergo a sudden transition to flaming (Interagency, 1987; Ortiz Molina et al., 1979; Williams, 1976). Flaming accelerates the process but is not a necessary event (Babrauskas, 1996).

Smoldering is characterized by an exothermic heterogeneous combustion reaction that occurs in the interior of porous combustible materials. The heat released during the heterogeneous oxidation of the solid is transferred toward the unreacted material by conduction, convection, and radiation, supporting the propagation of the smolder reaction. The oxidizer, in turn, is transported to the reaction zone by diffusion and convection. These transport mechanisms influence not only the rate at which the smolder reaction propagates but also the limiting factors of the smolder process, that is, ignition and extinction (lower bounds) and transition to flaming (upper bound). The propagation of the smolder reaction is, therefore, a complexly coupled phenomenon involving processes related to the transport of heat and mass in a porous media, together with surface pyrolysis and combustion reactions.

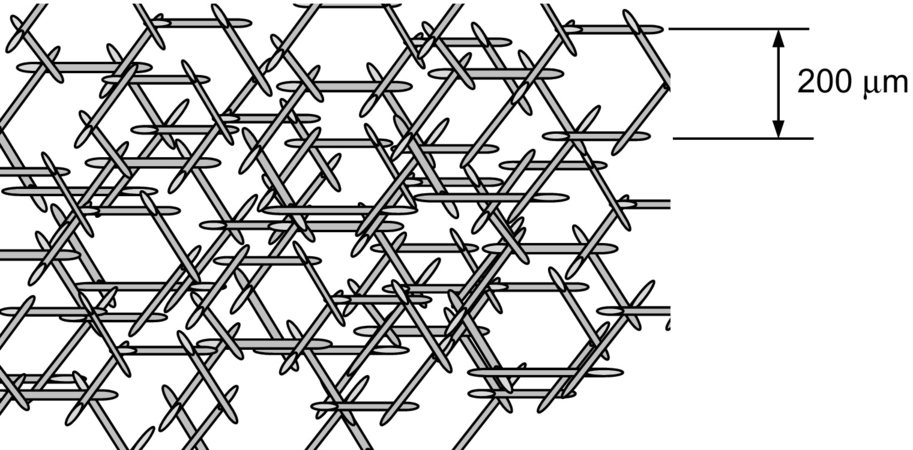

The main difference between smolder and any of the other combustion processes is that oxidation does not occur in the gas but rather in the condensed (e.g., solid) phase. Solid fuels that sustain smoldering are porous in nature; therefore, inside the porous matrix, the volume-to-surface-area ratio for the fuel is very small (Fig. 18.1). The oxidizer therefore has a large reaction surface with which to interact, and diffusion of oxygen to the fuel surface is faster than fuel evaporation. The result is a reaction that will propagate as the conduction heat transfer wave heats the porous solid.

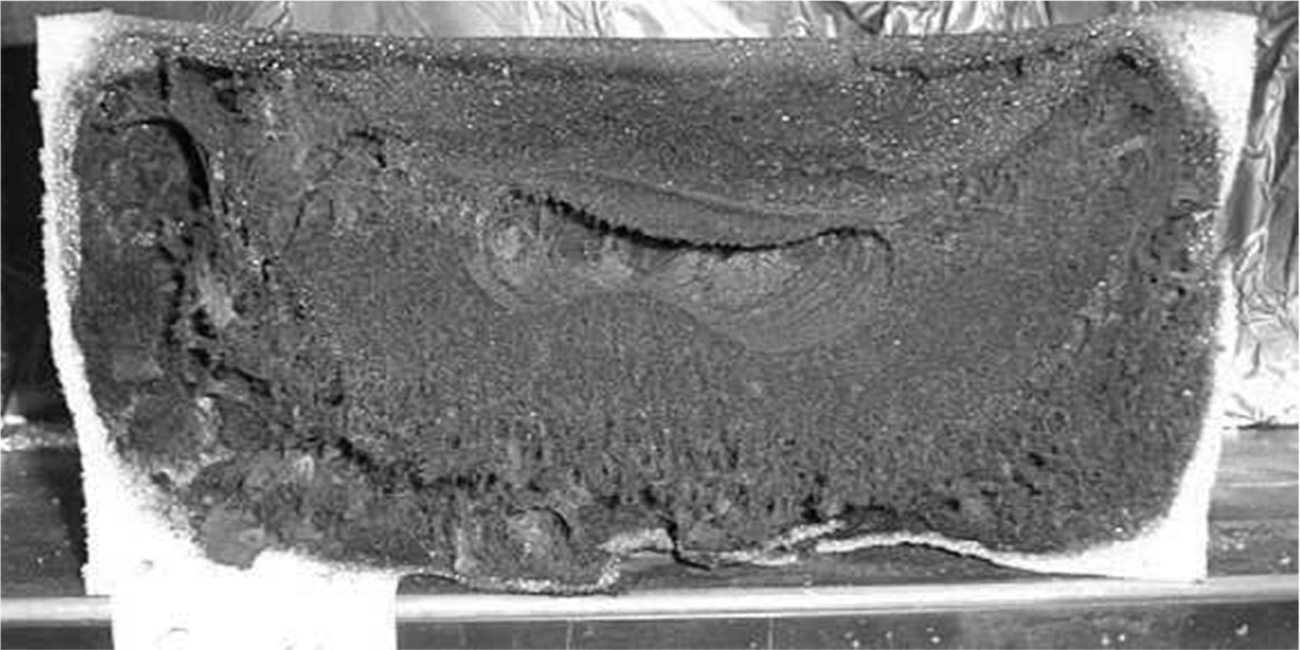

As the reaction propagates, the oxygen inside the porous matrix is completely consumed leaving residual fuel, generally referred to as “char.” Fig. 18.2 shows a picture of smoldered polyurethane foam. The foam was ignited at the top of the sample, and the reaction was allowed to propagate downward leaving a black char behind.

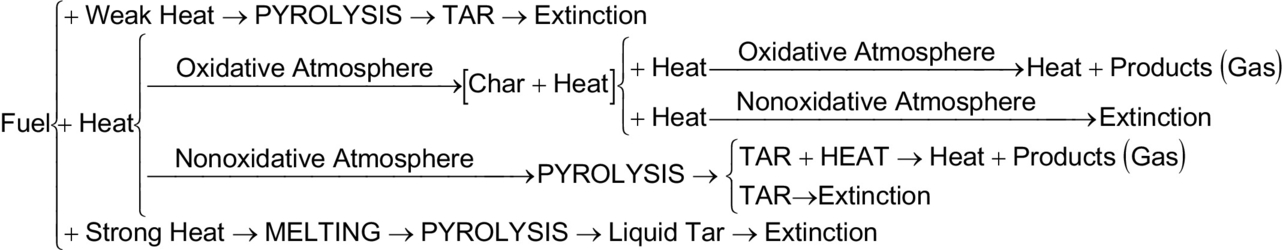

A smoldering reaction is not always established when heat is applied to a porous fuel susceptible to smolder. Actually, the conditions for the onset of smoldering are in some cases very restrictive. Fig. 18.3 presents the possible pathways established as viable when heating a solid, porous fuel susceptible to smoldering.

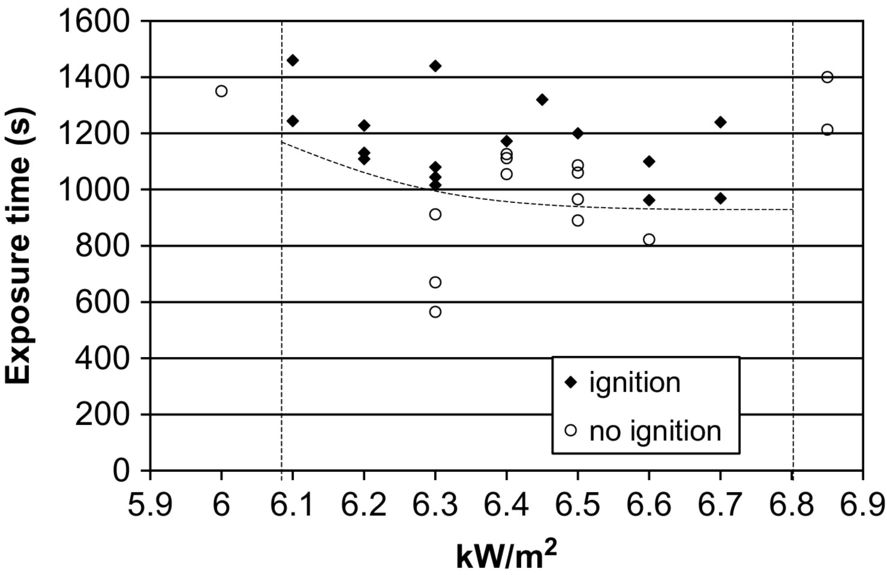

The first step of the degradation process, as shown in Fig. 18.3, corresponds to the different magnitudes of the net heat flux imposed to the material. If the net heat flux is weak (i.e., for polyurethane foam < 6 kW/m2), Fig. 18.3 shows that the fuel is degraded via pyrolysis. Nonetheless, a degraded material is formed. This material is generally of liquid form and is commonly referred as tar. If the net heat flux is very strong (i.e., for polyurethane foam > 7 kW/m2), a similar process is observed where a liquid tar remains as the product of the degradation. Both degradation branches are endothermic, and once the external heat source is withdrawn, extinction follows. The main difference between the two branches seems to be that the amount of heat determines the fraction of tar that will be evaporated, thus the production of airborne aerosols. A typical ignition plot is presented in Fig. 18.4 for polyurethane foam.

Smoldering of the material occurs only when the heat flux imposed on the material is in between the two limits described above. In the presence of an oxidative atmosphere, an exothermic surface reaction (smolder) will lead to the release of heat and gaseous products and the formation of a residual char. Char is a solid matrix that generally conserves the structure of the original fuel. The char has higher carbon content than the original solid and is more combustible. The char can further react in the presence of oxygen if its temperature is high enough. Reaction temperatures of char have been observed to be higher than the temperatures observed during direct smolder of the fuel. The final products are in most cases in gaseous form and particulate (smoke), but some fuels lead to a residual, noncombustible ash. If all the oxygen is consumed by the smolder reaction, the char will not react, and cooling will follow.

Even under the appropriate heating conditions, if not enough oxygen is available; the decomposition chemistry will privilege the endothermic pyrolysis of the fuel. This will again lead to the formation of tar and consequent extinction. Attempts to identify the exothermic and endothermic degradation processes have been made by means of thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) (Bilbao et al., 1996). These methods can provide important and insightful information about the smolder mechanisms; unfortunately, the results must be analyzed in a somewhat circular and iterative manner, where one must propose a model and see how TGA/DSC corresponds to it, and back and forth.

Once the smolder reaction has been initiated, the reaction front propagates across the porous matrix. The chemical processes occurring in the reaction front can be described in different ways, with the simplest being a one-step reaction. The determination of the number of steps required to model the reaction front depends on many variables. A brief summary of the different models available is presented by Rein et al. (2006). The fine balance between the energy generated, oxygen flow/consumption, and heat transfer/loss that will direct decomposition of the fuel to one of the specific branches is controlled by many factors such as buoyancy, geometry, oxygen concentration, external heat supply, relative location of the reaction front, and fuel.

This discussion of fundamentals has primarily focused on porous solid fuels because these have underpinned the majority of research on smoldering to date. Smoldering of NAPLs shares many similar characteristics, and while much less work is available because of its novelty, the majority of the fundamentals described above are expected to hold. For example, a similarly fine mass and energy balance is required for self-sustained conditions; however, the fuel is a typically a long-chain hydrocarbon or a mix of hundreds of hydrocarbons (e.g., crude oil and coal tar), so its pyrolysis and oxidation chemistry will be complex and unique. The main differences from smoldering of solids that do exist result from the fact that the fuel is distributed as a liquid occupying some or all of the porosity within an inert matrix (e.g., sand and soil). So, for example, the porosity of the systems are typically different, with porous solids like Figs. 18.1 and 18.2 at greater than 90% compared with sands typically around 35%. Also, the volume-to-surface-area ratio of the fuel is expected to be greater than the very small values for foam. Moreover, the effective permeability to air, which dictates the mass flux of oxygen through the reaction for a given pressure gradient, will be significantly less in the NAPL/soil system. Also the effective heat capacity of the sand, which dominates the sand/NAPL system, greatly exceeds that of highly porous solid fuels. All of these will have an effect on heat and mass transfer characteristics and the extinction limits of the process. Also, it affects the reaction kinetics and completeness, so, for example, it is typical that with a high heat capacity and forced airflow in NAPL/sand systems, no char will remain after the reaction passes. As with solid fuels, for the case of NAPL/soil systems, detailed understanding of these processes and process limits and the practical implications for soil remediation can only be achieved via studies at different scales.

18.3 Small scale

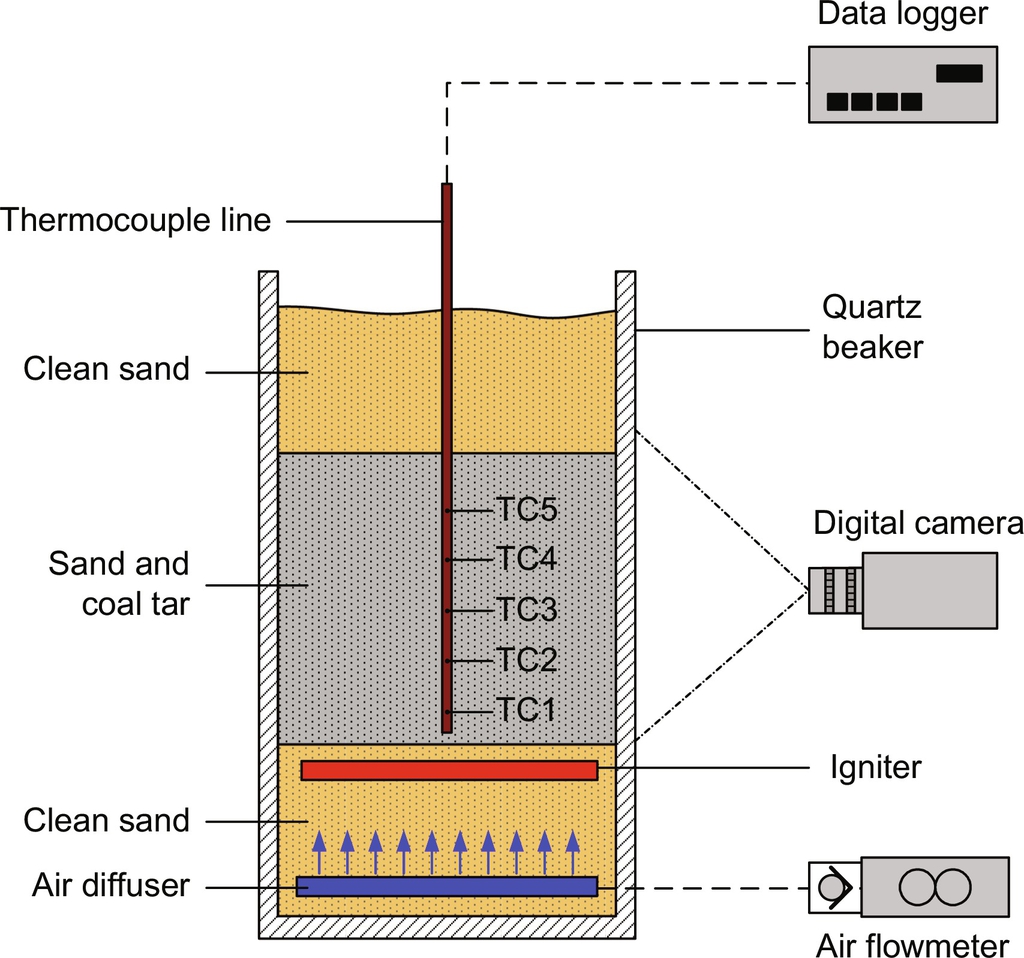

To systematically study the different mechanisms controlling smoldering of NAPLs, it is necessary to conduct a multiplicity of experiments using a small-scale setup. Pironi et al. (2009) used a cylinder of 100 mm in diameter and a height of 175 mm to sustain smoldering of a liquid fuel for the first time. A schematic diagram of the experimental apparatus is shown in Fig. 18.5. Upward smoldering combustion tests were carried out with coal tar. Inert sand (Leighton Buzzard 8/16 sand, WBB Minerals) of bulk density of 1.7 kg/m3, porosity of 0.40, and diameter of the grains in the range of 1–2 mm was used as a porous medium. The fuel/sand mixture to be studied was prepared by mixing coal tar and coarse sand in a mass ratio corresponding to the desired saturation level of the sand pack. The saturation of the sand pack indicates the fraction of the pore volume filled with fuel; for the base case considered in this work (25% saturation), the corresponding amount of fuel per unit volume is 0.12 kg/m3. The maximum power used for these experiments was of approximately 320 W, which corresponds to a heat flux of 41 kW/m2 over the area of the horizontal section of the beaker.

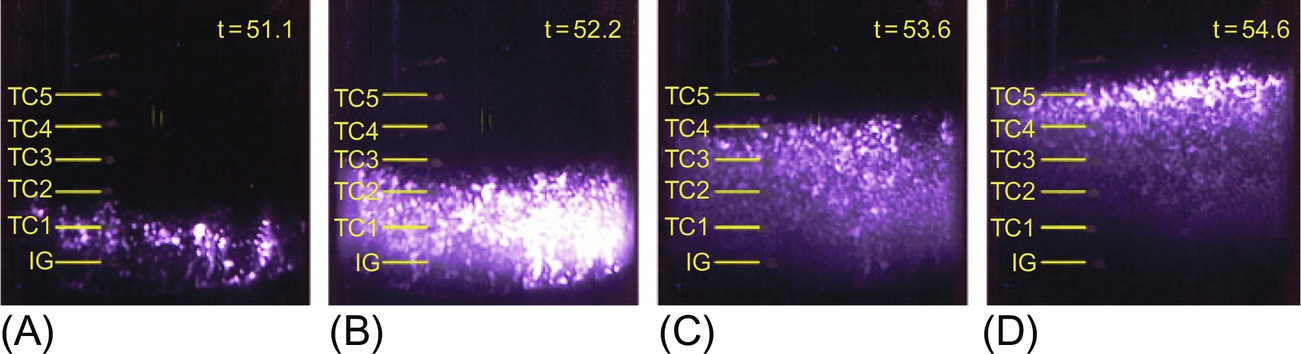

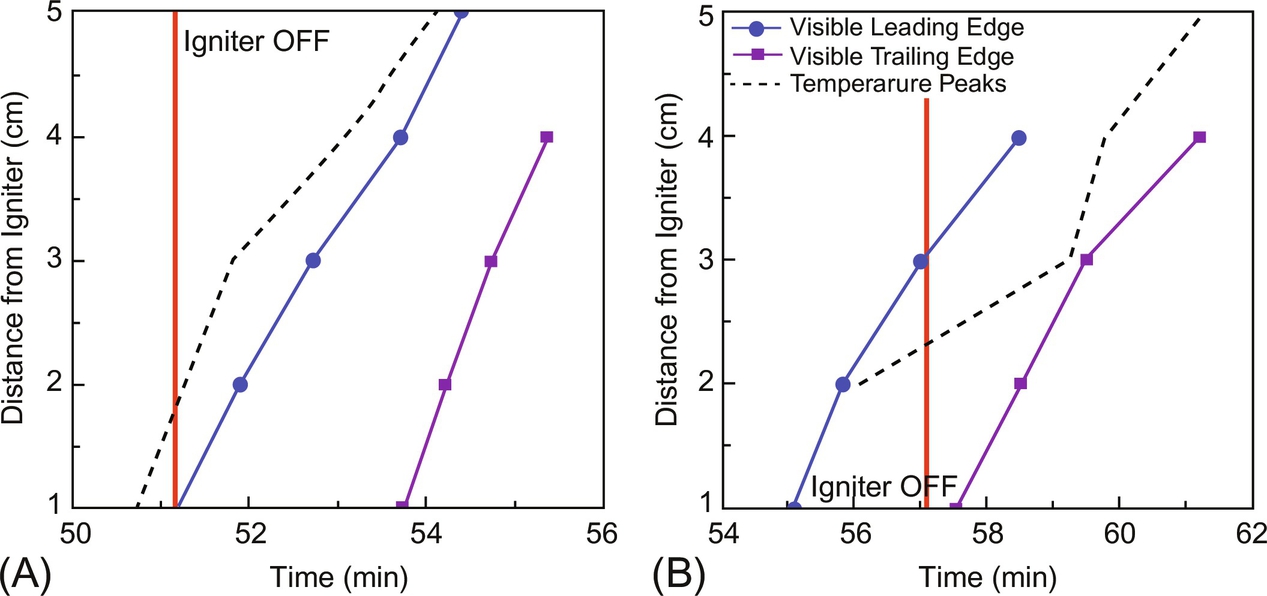

The smoldering velocity is calculated from the time lapse of the front arrival at two consecutive thermocouples and the known distance between thermocouples. Images from the digital camera captured the propagation of the visible part of the smoldering front (Fig. 18.6). CO/CO2 ratios proved to be a good indicator that an oxidative reaction was occurring. Fig. 18.6 shows the upward propagation of the front in the sand for a Darcy airflow velocity of 16.2 cm/s and a coal tar saturation of 25% as an illustration example. Similar observations could be made for other conditions. Although visible images are not a direct indication of the location and intensity of the reaction, they provide a qualitative description of the reaction front. The four images represent different moments in time. It can be seen that as the reaction front propagates through the contaminated porous media the reacting region increases in size. While propagation of the leading edge is controlled by heat transfer and the presence of oxygen, the trailing edge is controlled by total fuel consumption. It is important to note that all the oxygen is therefore not consumed at the reaction front, but it filtrates through the porous media allowing for a thick reaction front. Fig. 18.2D shows that eventually, the fuel will be consumed and the region close to the igniter will cease to react. It is important to note that if the luminous intensity can be used as an indicator of the reaction rates, the intensity of the reaction initially increases (Fig. 18.2A and B), but once the ignition has been fully attained, a peak intensity is reached (Fig. 18.2B), and then, a dilution process follows (Fig. 18.2C and D). Oxygen will be consumed through the entire reaction region, and since the oxygen supply is fixed, the broader the reaction zone, the weaker the local smoldering. Image processing showed that the maximum luminous intensity was always at the leading edge of the reaction front.

Fig. 18.7A shows the temperature histories for the images presented in Fig. 18.6. The thermocouple traces confirm the progression established by the luminous intensity, where peak temperatures are attained by TC2 followed by a gradual decay. Furthermore, it can be seen that once the airflow is increase to the test value a sudden increase in temperature occurs showing the onset of a strong exothermic reaction. An important observation is that once the leading edge of the front has passed a thermocouple, the temperatures remain high for a short period of time and then decrease rapidly. Smoldering can occur through a wide range of temperatures; therefore, some oxidation seems to remain after the initial front has passed. The initial reduction of the fuel content might be the reason behind the reduction in temperature. This observation is important for remediation because it indicates that while most of the fuel is consumed with the initial front, continuation of the reaction is necessary for a complete cleanup of the soil.

Fig. 18.7B shows a particularity of self-sustained smoldering at a small scale; the leading and trailing edges of the reaction front progress at the same rate. After each experiment, the sand was excavated, and the degree of remaining contamination was visually estimated. In some cases, samples were analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis and the gas products obtained by gas chromatography in order to assess the extent of fuel destruction and removal from the soil. No observable contamination was detected by visual inspection of sand coming from the central part of the beaker. A change of the sand color to red, attributable to iron oxidation, was indicative of exposure to high temperature (in excess of 600°C) for a long time. Samples taken from the sand in proximity of the beaker walls revealed the presence of visible residual contamination. While the images show a strong reaction through the extent of the sample, it is clear that in these zones, heat losses caused the extinction of the weaker residual smoldering reaction before complete conversion of the fuel. The mixture of sand and residual coal tar after cooling showed the presence of char not fully consumed. Gravimetric analysis following extraction by dichloromethane (DCM) revealed average rates of removal of 99.95% and 98%, respectively, for samples taken from the center of the beaker and in proximity of the walls. Volatile compounds (BTEX), determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, were reduced down to not detectable levels in both the classes of sample.

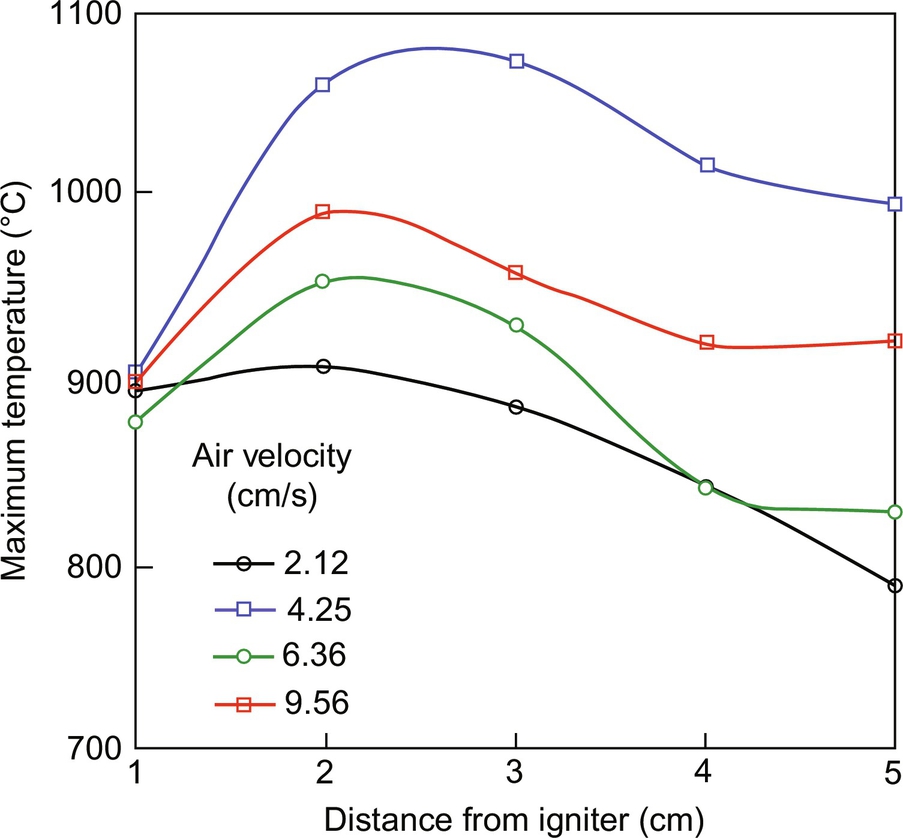

Higher injected air velocities result always in faster propagation (Fig. 18.8) but not necessarily in higher temperatures (Fig. 18.9). This is typical of combustion in porous media and is mainly associated to the fine balance between oxygen consumption and heat transfer. The variation of the peak smoldering temperature along the sample is presented in Fig. 18.10 for the different airflow velocities. Peak temperatures at each location ranging from 789 to 1073°C were observed, with the highest values attained for the 4.25 cm/s airflow velocity. As mentioned before, it can be seen that peak temperatures are higher in the middle of the sample and decay toward the top end of it. As shown in Fig. 18.6, the reactive region width is increasing; therefore, the oxygen concentration is expected to decrease as the reaction propagates leading to lower peak temperatures. Furthermore, for the lower air velocities, the reaction temperatures decrease below extinction values before the front reaches the end of the sample. The observed decay and extinction of the process in these experiments is indicative of weak propagation away from the igniter region. When propagation is weak, heat losses play a significant role. The effect of the heat losses to the external environment is to hamper smoldering propagation. In simple terms, the propagation velocity is proportional to the difference between the heat generated by the combustion and the heat lost to the exterior. A more detailed analysis is presented in (Bar-Ilan et al., 2004). It is important to note that the importance of the heat losses decrease as the area of the cross section of the reactor increases, due to a reduced surface-area-to-volume ratio, for the sample; therefore, a stronger smoldering process is expected at larger scales.

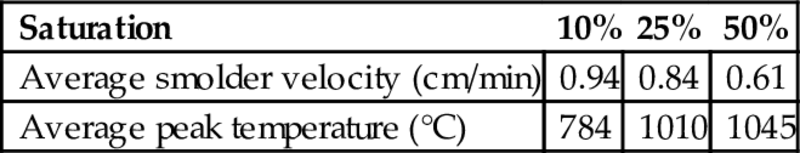

A set of tests were run varying the fuel saturation of the sample. The amounts of coal tar contained in the soil for each case were approximately of 0.048 kg/m3 (10% saturation), 0.12 kg/m3 (25%), and 0.24 kg/m3 (50%). The inlet airflow was kept at a Darcy velocity of 4.25 cm/s. The results for the propagation velocity and peak temperature of these experiments are shown in Table 18.1. These results indicate that as the saturation increases the smolder velocity decreases approximately linearly, which confirms that for this range of saturation, the reaction is oxygen controlled. The results also indicate that the peak temperature increases with the fuel saturation.

18.4 Intermediate scale

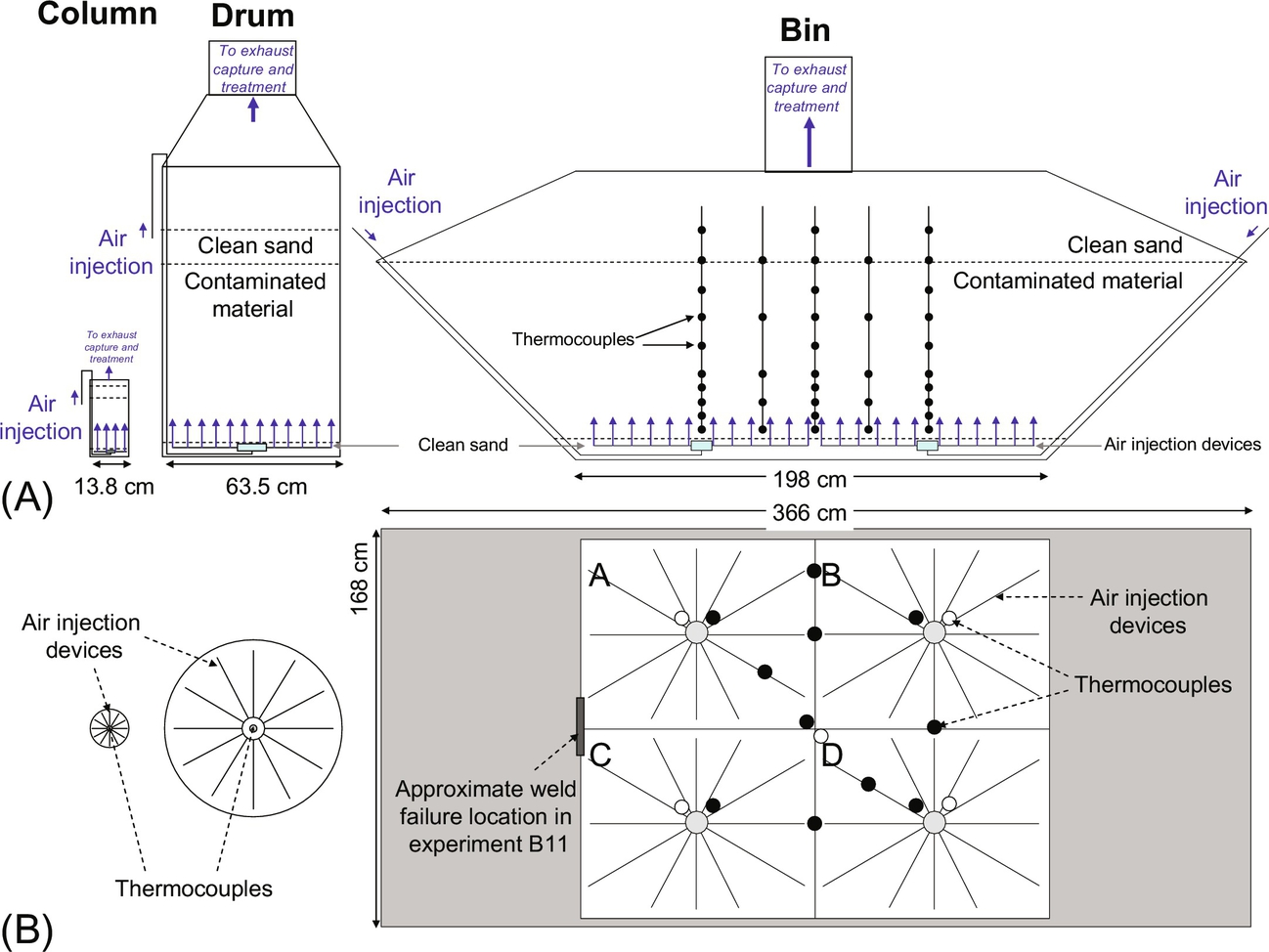

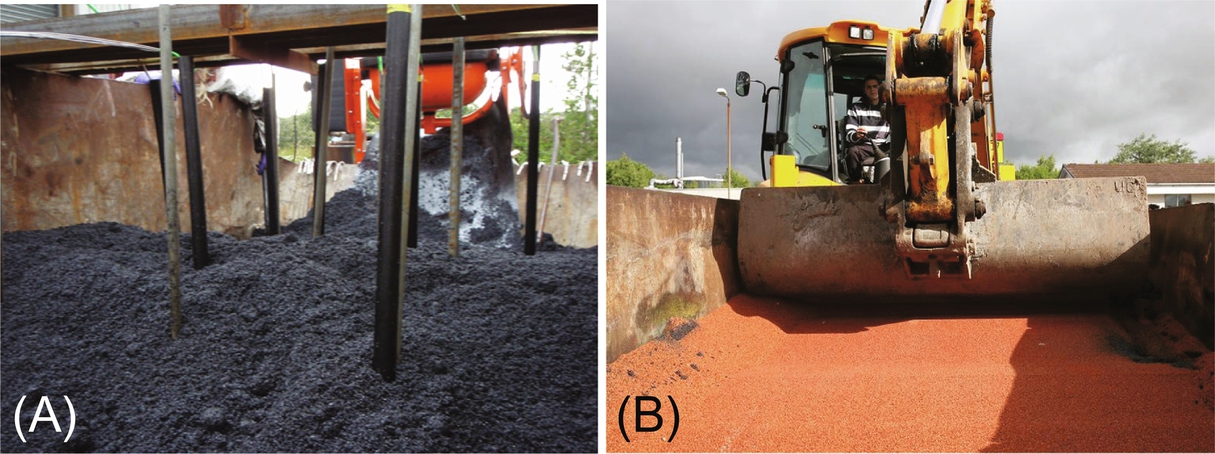

A series of intermediate-scale experiments were conducted to extrapolate the small column results presented above (Switzer et al., 2014). Drum (intermediate-scale) experiments were carried out in a 0.3 m3 oversize chemical drum (63.5 cm outer diameter and 104.1 cm height) designed almost identically to the column described above, representing a 100-fold volumetric scale-up. An air diffuser was embedded at the base of the drum and covered with a thin layer of sand. Three-coiled 3.8 m Inconel-sheathed heaters (240 V and 2000 W, Watlow Ltd, the United Kingdom) were emplaced above the air diffuser. The drum was packed with contaminated material to a depth of 40 cm and covered with 75 kg of clean sand, a depth of approximately 10 cm (Fig. 18.10A). The top of the drum was open to the atmosphere and operated under a purpose-built exhaust hood.

Bin (large-scale) experiments utilized a 3 m3 chain-lift style dumpster as the experimental vessel, representing a scale-up of 10-fold from the drum and 1000-fold from the column. The base was 168 × 198 cm and the horizontal cross section increased to 168 × 366 cm at a height of 85 cm (Fig. 18.10A). Four air diffusers, similar in design to the drum experiments, were employed (Fig. 18.10B), effectively establishing the vessel as a four-quadrant simultaneous experiment for hardware installation and monitoring purposes; no physical divisions were embedded. The air diffusers were buried in a thin layer of clean sand layer. Twenty 3.8 m Inconel sheath cable heaters were laid across the clean sand lengthwise across the base. Contaminated material was loaded to a height of 80 cm. A clean sand layer of 5–15 cm was placed on top and heaped toward the center. The top boundary was open to the atmosphere and operated under a purpose-built exhaust canopy.

Surrogate contaminated soil was created by mixing coal tar with coarse sand in batches and loading them into them into the drum and bin, achieving starting concentrations of 46,400 and 31,000 mg/kg, respectively. In the bin experiments, approximately 80 thermocouples were divided into 16 vertical arrays of 5 sensors to avoid clusters of thermocouple rods forming large voids and preferential pathways that would disrupt the smoldering process (Fig. 18.10). The first two thermocouples were spaced 10 cm apart, and the remaining thermocouples were spaced 20 cm apart. Two arrays of thermocouples were placed at the center of each quadrant and the overall center of the bin, staggered to ensure thermocouples were present at 10 cm intervals to a depth of 80 cm; further, single arrays were deployed at interfaces between each of the quadrants (Fig. 18.10B).

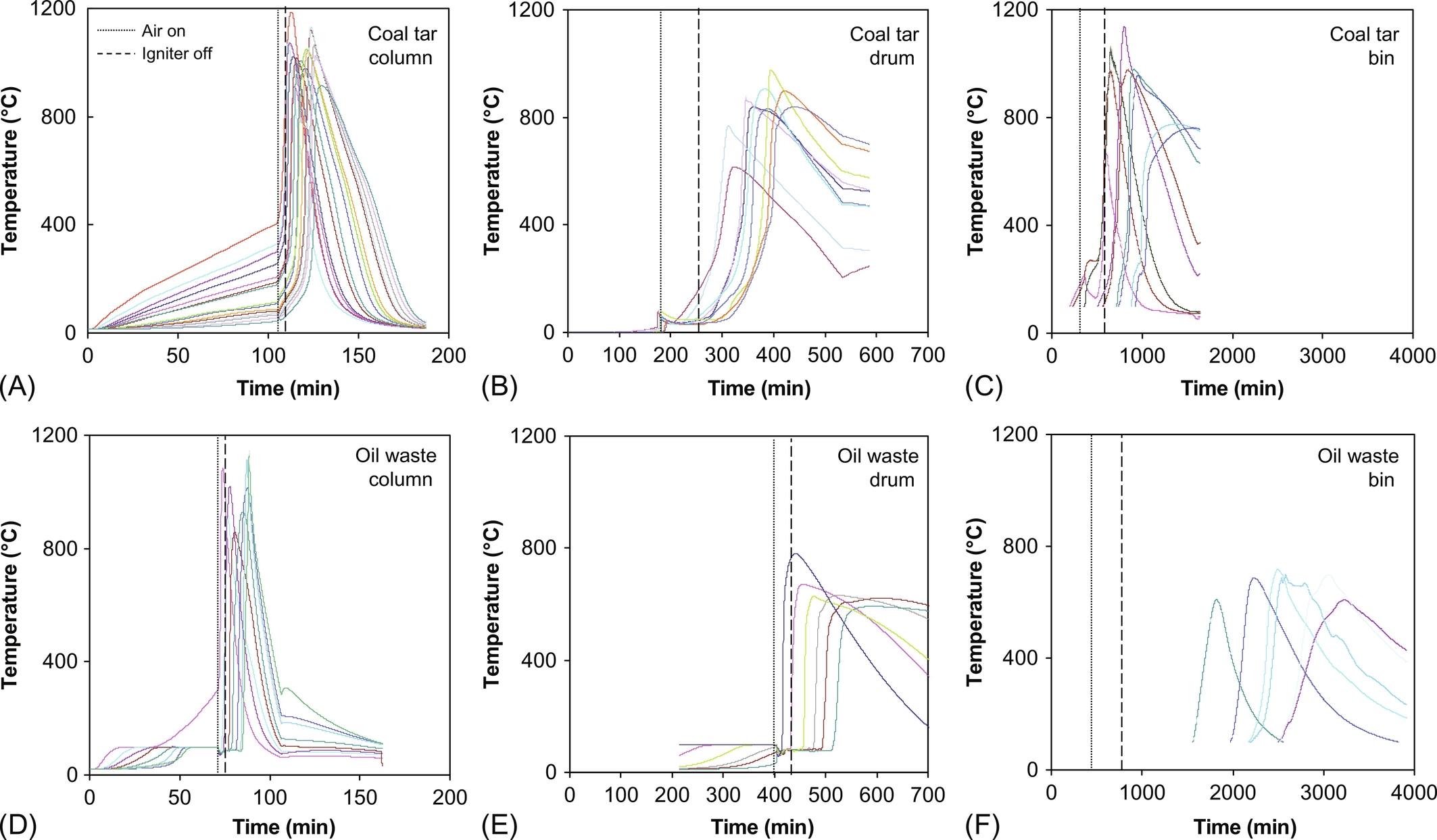

The characteristic temperature evolution was observed at all thermocouple locations throughout the vessel (Fig. 18.11). While temperature evolutions reflected heterogeneities in packing and airflow delivery, the characteristic values were consistent with small-scale experiments. Imbalances generated by heterogeneities were overcome as the smoldering front moved upward through the porous material, consistent with a previous experiment (Pironi et al., 2009). Peak temperatures ranged from 800 to 1000°C as self-sustaining smoldering propagated through the vessel for approximately 6 h for the drum and 20 h for the bin before the reaction self-terminated when insufficient fuel remained. Complete smoldering was observed at all locations, indicating robustness of the process in the presence of sufficient fuel and oxygen.

Excavation of the experiments showed visibly clean material throughout the vessel (Fig. 18.12 for the bin). Postremediation contamination levels were an average of 17 ± 3 mg/kg (30 samples) throughout the bin and 10 ± 1 mg/kg (20 samples) in the area that was initially contaminated. This reduction in concentration represents 99.95% remediation across the 3 m3 vessel. Slightly elevated contamination levels were observed on the surface, but these were all below 100 mg/kg and likely related to condensation of volatiles in the clean sand cover.

18.5 NAPL mobility

Potential mobilization of the fuel within the porous matrix is a unique issue for liquid fuels relative to solid porous fuels in the context of smoldering. Moreover, increases in scale enhance the importance of NAPL mobility. Considering NAPL mobility in the context of smoldering requires a new conceptual model. Fig. 18.13 illustrates a snapshot of the vertical distribution of temperature and oxygen concentration for a smoldering reaction traveling upward in a one-dimensional column (Kinsman et al., 2017). The column contains a high viscosity NAPL (e.g., coal tar) embedded in an inert matrix (e.g., quartz sand) at a given saturation with the remaining porosity occupied by air. In the ambient region ahead of the front, NAPL and soil are at ambient temperatures (T∞), and the NAPL is therefore unchanged physically or chemically. In the preheating region (e.g., 50–200°C), soil and NAPL are absorbing energy transmitted via conduction (through soil/NAPL) and convection (of heated air) from the smoldering front below. In the presence of the higher temperatures (e.g., 200–350°C) and lower oxygen concentrations of the pyrolysis region, the NAPL undergoes endothermic, nonoxidative decomposition of the fuel (Torero and Fernandez-Pello, 1996). These pyrolysis reactions are expected to convert the NAPL into a char, which is immobile. The top of the oxidation region, demarking the leading edge of the smoldering front, exists where the NAPL smoldering ignition temperature (Ts) is exceeded (e.g., > 350°C) and oxygen concentrations are high, and therefore, exothermic oxidation reactions occur. In this region, oxygen is consumed, NAPL (now char) is consumed, and energy is generated leading to a characteristic peak temperature observed for the given contaminant (Tmax).

The trailing edge of the smoldering front occurs at the point of total fuel consumption, below which no NAPL remains. Since they are governed by different processes, the velocities of the leading and trailing edges of the smoldering fronts (Vleading and Vtrailing) are not necessarily equal. Vleading will generally be controlled by the rate that heat is transferred forward, while Vtrailing is determined by the rate of mass destruction, which is dictated primarily by combustion chemistry and oxygen mass flux. When Vtrailing < Vleading, the smoldering front thickness will expand with time.

Just above the trailing edge in the oxidation region, temperatures are relatively low, so chemical reactions are relatively slow, and oxygen is slowly consumed. Oxygen consumption will result from a complex function of the relative speed of the oxidation with respect to residence times (i.e., Damköhler number). Closer to the leading edge the temperatures will be higher, the reaction rates faster and therefore oxygen consumption will be more significant. In the cooling region, all NAPLs have been consumed, and the inert porous matrix experiences decreasing temperatures due to heat loss, primarily via convection from the ambient temperature air injected below.

There is the potential for NAPL mobilization in the preheating region. NAPL may migrate at a certain velocity (VNAPL) depending on the NAPL viscosity and the NAPL hydraulic gradient. The direction and magnitude of the gradient depend primarily on the relative influence of gravity and the forces induced by upward flowing air. At ambient temperatures, the high viscosity of long-chain hydrocarbons means migration is slow even in the presence of significant hydraulic gradients (Gerhard et al., 2007). However, liquid viscosity decreases rapidly with increasing temperatures (Potter and Wiggert, 2002), and therefore, VNAPL may increase in the elevated temperatures of the preheating region. NAPL viscosity may decrease by a factor of 10–1,000,000 over this temperature range, and the sensitivity to temperature is highly dependent on NAPL chemistry.

Reduction of NAPL viscosity ahead of a heating front is known to result in mobilization in numerous applications. In situ combustion for enhanced oil recovery (Thomas, 2008) and steam injection for remediation (Kaslusky and Udell, 2005) take advantage of heat-induced viscosity reductions to mobilize residual NAPL. NAPL is intentionally mobilized for its recovery in those cases, and it is therefore applied in a horizontal sweep configuration in the subsurface; of course, NAPL loss via downward remobilization can also occur (Kaslusky and Udell, 2005). In the context of smoldering treatment of NAPL-contaminated soil in a vertical column (or applied as an ex situ vertical reactor), the reaction is traveling upward, and NAPL has the potential to migrate downward into the smoldering front (Fig. 18.14). NAPL migration could conceivably affect smoldering in numerous ways including changing the spatial distribution of the fuel (reduced NAPL saturations ahead of the front and increased saturation closer to the front), addition of extra fuel (i.e., energy) to the smoldering reaction, addition of a heat sink (i.e., colder fuel from above) to the reaction, or even penetration of the fuel through the reaction contaminating the cleaned soil below.

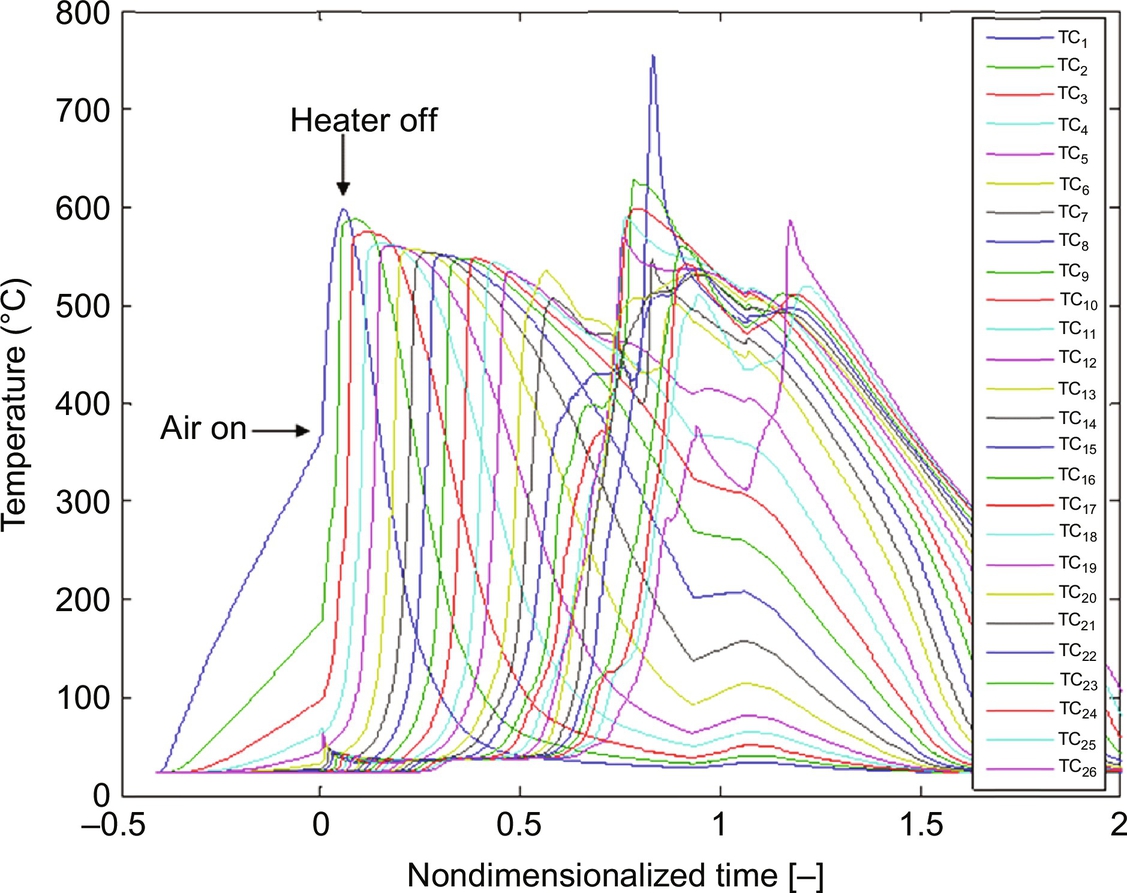

Fig. 18.14 shows the temperature history for the 90 cm column with a forced Darcy air flux of 2.5 cm/s. This experiment displayed typical smoldering behavior from approximately TC1 to TC12, including constant velocity of the leading edge (0.41 ± 0.07 cm/min) and trailing edge of the smoldering front (0.32 ± 0.07 cm/min) and consistent peak temperatures (564 ± 17°C). However, atypical behavior is observed beginning at nondimensionalized time (NDT) = 0.6. Kinsman et al. (2017) choose to nondimensionalize the time by the time required to reach the end of the contaminated soil sample. The steady progression of the front is interrupted and both dips and spikes in temperature are observed beyond this time. Understanding what at first appears to be chaotic behavior is assisted by examining individual thermocouples. As described previously, TC4 displays typical smoldering behavior. At TC14, ignition of smoldering is similar; however, it is interrupted before reaching standard peak temperature. The interruption consists of a cooling period followed by a second ignition event that results in a peak in temperature. Only after this peak is achieved is typical cooling behavior observed. This pattern is repeated for all TCs after NDT = 0.6, and the temperatures of these second peaks continue to increase, as shown in Fig. 18.14. As a result, the upper half of the column sees peak temperatures as high as 750°C, far beyond the typical peak smoldering temperature in the lower half (564 ± 17°C).

The most likely explanation for this is that very unusual smoldering behavior is downward NAPL migration. Consider TC14; (i) NAPL in the preheating zone, exhibiting reduced viscosity due to elevated temperature, migrates downward at a high enough rate or in a sufficient quantity that it impinges this location when the NAPL smoldering front is just arriving; (ii) this migrating NAPL is cooler than the combustion temperatures at TC14, acting as a heat sink; (iii) energy at TC14 is consumed in preheating and pyrolysis of this new fuel, adding to the temperature decline; (iv) the mobilized NAPL, now pyrolyzed, provides additional fuel that ignites, causing reignition and renewed smoldering; and (v) as the leading edge of the smoldering front continues to advance upward, this process is also shifted upward, and the TC14 location is able to smolder to completion and cool. The fact that higher/later thermocouples exhibit more substantial temperature dips and higher peaks suggest the process becomes more significant with the larger preheating zone thicknesses that evolve in taller systems. This is the reason that these NAPL migration effects should be observed after NDT = 0.6 and not before in this experiment and are observed only in columns 90 cm and not 30 cm columns.

It is noted that, despite the observed effects of NAPL mobility on the reaction characteristics, NAPL was never found to have penetrated or bypassed the smoldering front. Rather, in all cases, the reaction accommodated the incoming NAPL by increasing the thickness of the reaction zone and all cases resulted in completely clean material at the end of the test. This indicates the robust nature of smoldering, its energy efficiency enabling it to consume all fuel even when the fuel is distributed heterogeneously and in a manner that varies with time.

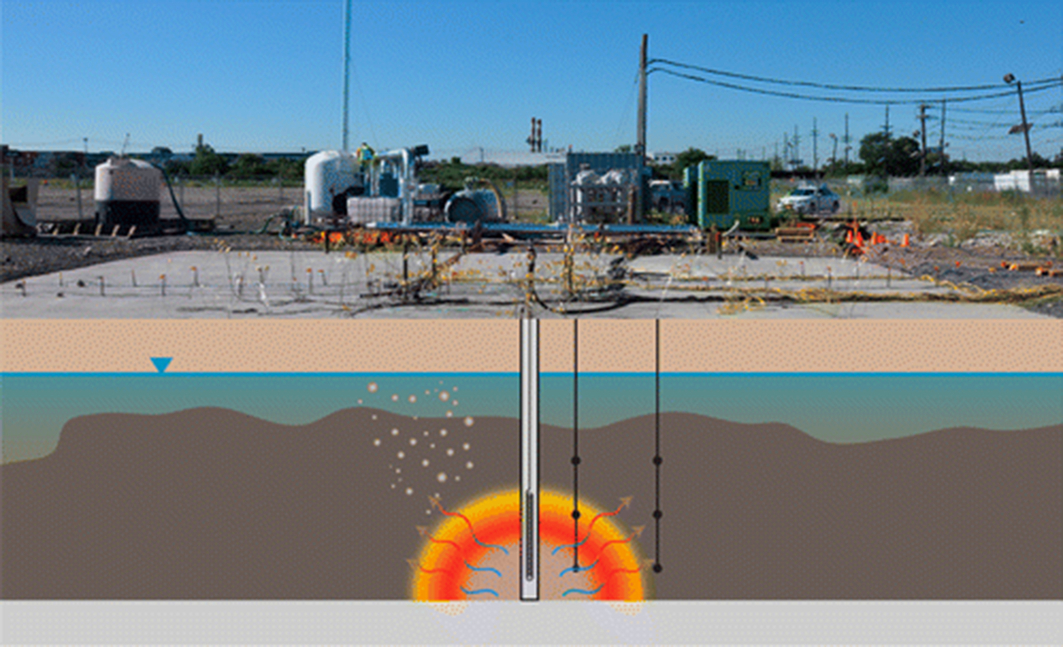

18.6 Large scale

Two large-scale pilot tests were conducted in the area of a backfilled lagoon at a contaminated site that was operated from the early 1900s until 1983 (Geosyntec, 2012) and are described by Scholes et al. (2015). The lagoon was 2.5–3.5 m deep and was used to dispose of coal tar and its by-products. Beneath this unit is a 0.3–0.6 m thick confining clay “meadow mat” layer composed of clay, silt, and peat. It is underlain by an alluvium unit, composed of medium to coarse sands up to 6 m thick (herein referred to as the “deep sand unit”). The water table at the site is approximately 1 m below ground surface. Coal tar DNAPL (denser-than-water NAPL) exists as a potentially mobile, highly saturated pool up to 1.3 m thick within the shallow fill unit upon the meadow mat. Coal tar is also present in the upper 4–5 m of the deep sand unit in locations where the original lagoon excavation activities appear to have removed the meadow mat, thereby providing pathways for DNAPL migration into this deeper unit. The two pilot tests consisted of one in the shallow fill unit, referred to as the “shallow test,” and a “deep test” conducted in the deep sand unit below the same lagoon and adjacent to the shallow test cell (Fig. 18.15). Each test area had a centrally installed 5 cm diameter stainless steel well with a 30 cm long wire-wrapped (10 slot) screen that served as the ignition well and for delivering heat and air. In both cases, the screen was located near the base of a significant coal-tar-contaminated interval as detected by investigational borings. Custom-built, removable, down-well electric heaters were used to ignite NAPL adjacent to the ignition wells via convective heat transfer. The heaters were turned off following ignition (confirmed by the detection of combustion gases in collected vapors), and air injection flow rates were manipulated manually at the well to maintain and propagate the combustion front in a self-sustaining manner. A vapor cap was installed to control and monitor combustion gases and vapors for both tests. Within each vapor cap, vertical or horizontal extraction conduits were emplaced to collect vapors for the shallow and deep tests, respectively. Direct-push coring methods were used to collect pre- and posttest soil samples.

A self-sustained smoldering reaction was maintained below the water table in both pilot tests, for 12 days and 11 days in the shallow and deep tests, respectively. The mass of coal tar destroyed in the shallow and deep tests were estimated to be 3700 and 860 kg, respectively. Mass destruction rates ranged from 1 to 43 kg/h in the shallow test and 1–7 kg/h in the deep test. Changes in combustion gas (CO and CO2) concentrations versus time in extracted vapors from the shallow and deep tests reveal the strength of the reaction, thus indicating where intervention is necessary (either reignition or a new well for airflow).

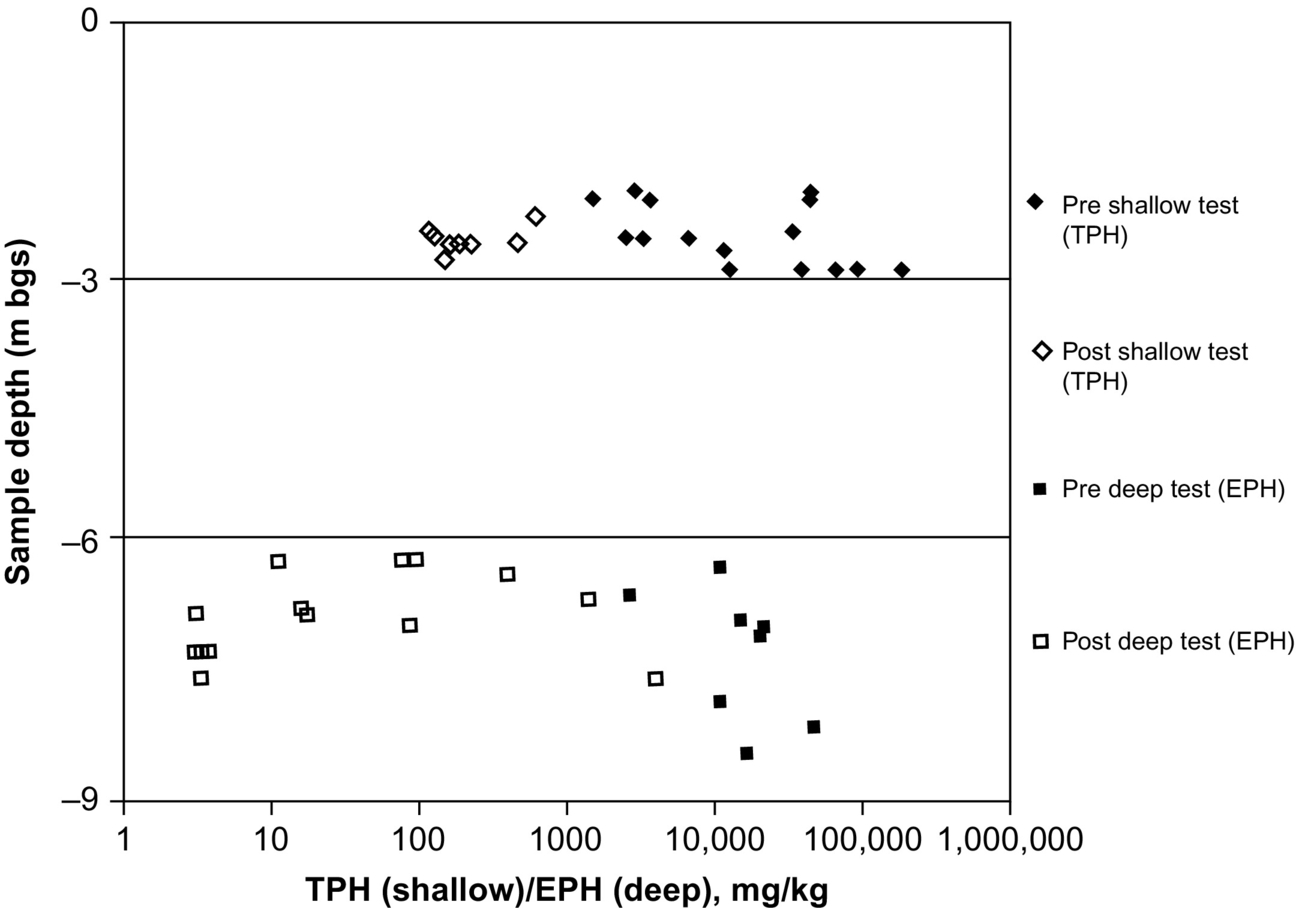

Soil contaminant concentration was reduced in the shallow test cell from a mean pretest concentration of 37,900 mg/kg (n = 15 and standard deviation = 50,800 mg/kg) to a mean posttest concentration of 258 mg/kg (n = 8 and standard deviation =185 mg/kg) equating to an average remediation efficiency of 99.3%. In the deep test, it was reduced from a mean pretest concentration of 18,400 mg/kg (n = 8 and standard deviation = 13,400 mg/kg) to a mean posttest concentration of 450 mg/kg (n = 14 and standard deviation = 1100 mg/kg) for an average remediation efficiency of 97.6%. Fig. 18.16 presents the concentrations of all pre- and post-field test soil samples collected from within the treatment areas for the shallow and deep field tests as a function of depth of sample. Posttest soil cores from both pilot tests (eight from the shallow test and nine from the deep test) from within the combustion zones indicated no NAPL and visibly reduced moisture levels. Gas analysis on the recovered emissions revealed that less than 2% of the coal tar was volatilized, indicating that in situ destruction by combustion (rather than mobilization or mass/phase transfer) was responsible for this extensive remediation.

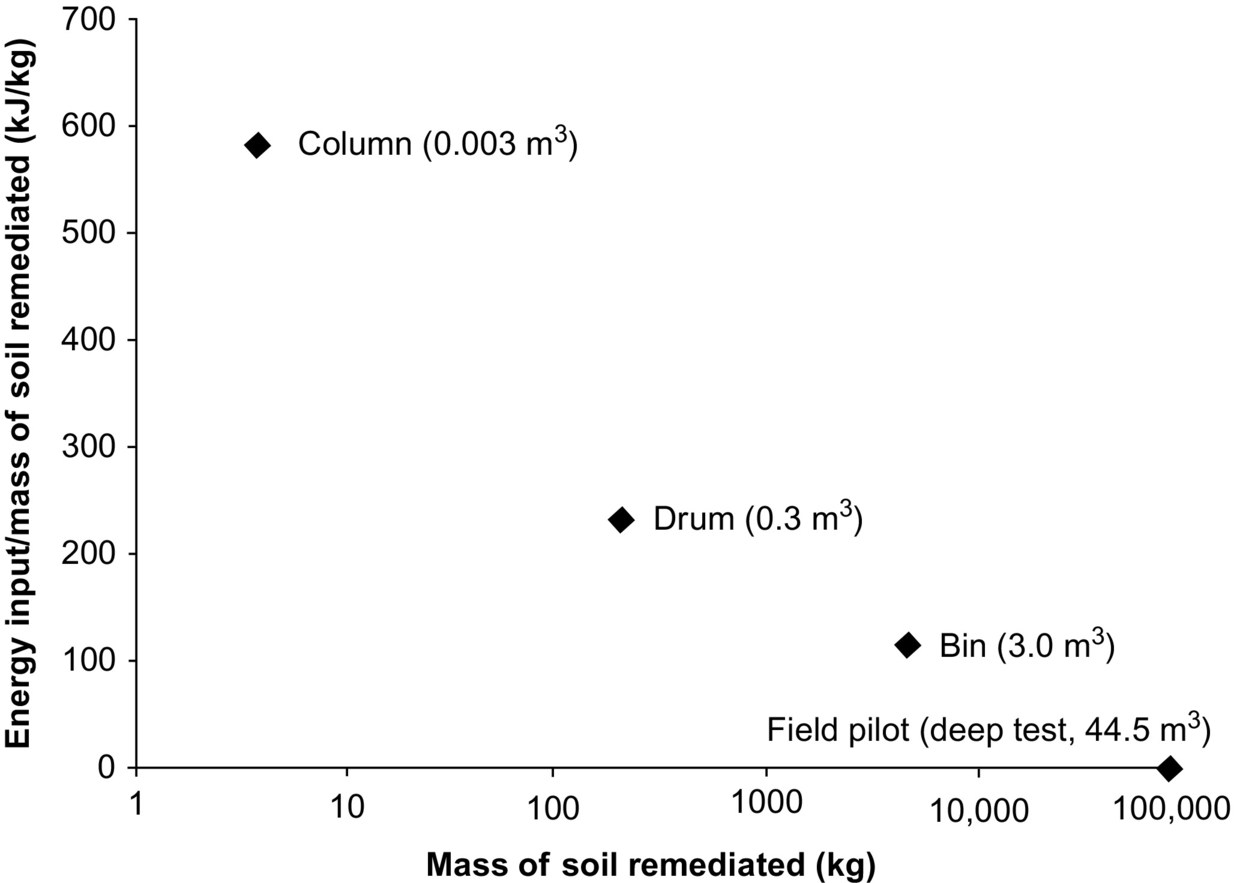

The energy for ignition in the deep test was estimated to be 1.1 kJ/kg of soil remediated based on achieving self-sustained smoldering following approximately 3 h of heater operation and resulting, after 10 days, in 44.5 m3 of soil remediated. Fig. 18.17 presents energy for ignition values as a function of scale and includes this calculated value for the deep test and the results of ex situ coal tar smoldering experiments conducted at a variety of scales by Scholes et al. (2015) and Switzer et al. (2014). This plot reveals that the self-sustained smoldering reaction becomes increasingly efficient (less heat energy input per mass of soil remediated) with increasing scale of application (note the logarithmic scale on the independent axis). This behavior is expected because heat losses to the external environment are reduced with increasing scale and the available radius of influence for a single ignition event increases substantially. This reveals a benefit of self-sustained smoldering, since all other thermal treatment methods utilize endothermic processes and require approximately constant and continuous energy input per mass of soil treated; for example, in situ thermal desorption typically requires between 300 and 700 kJ/kg at the field scale (Triplett Kingston et al., 2014). The short energy input required by self-sustaining smoldering relative to the potential treatment mass illustrates a clear benefit of smoldering, its energy efficiency.

The shallow and deep tests demonstrated ignition and propagation of a self-sustaining smoldering reaction in coal-tar-contaminated soils in situ and below the water table. In situ destruction of coal tar was observed at rates up to 43 kg/h resulting from a single ignition well, and smoldering fronts were found to propagate greater than 4 m from an ignition well at rates up to 1 m/day. In situ heterogeneity was observed to play a role in the rate and uniformity of smoldering front spread because it strongly influences the distribution of air. Although not determined in these tests, it is expected that the radius of influence of a single well will be determined by the distance where the local air velocity falls below a threshold (oxygen mass flux) required to sustain the reaction. Petroleum hydrocarbon concentrations in treated soils (i.e., from combustion zones) were reduced on average by 98.5%.

18.7 Other applications

Due to the high energy efficiency, smoldering combustion is an attractive alternative for the treatment of organic waste with high moisture content. High moisture content results in a low effective calorific value, necessitating substantial predrying or the use of supplemental fuel to avoid quenching of the combustion reaction. Smoldering combustion overcomes these limitations by efficiently transferring reaction heat to unburned fuel, enabling comparable timescales of combustion and heat transfer (Howell et al., 1996).

Smoldering combustion of feces was studied by Yermán et al. as part of a new integrated, low-cost, on-site sanitation system aiming to rapidly disinfect human waste using minimal resources (Yermán et al., 2015). This application shows the potential of smoldering for other forms of in situ management of waste (e.g., waste landfills). The reactor configuration was similar to that showed in Fig. 18.5. Experiments of feces mixed with sand were carried out in a stainless-steel column (16 cm inner diameter and 100 cm height). A porous matrix is created with the necessary heat retention and air permeability properties for smoldering combustion by mixing the feces with sand. Sand is used because it is a low cost and because it has been identified as an effective agent for increasing the porosity of fuels for the NAPL destruction (Pironi et al., 2009). To manage the regulatory challenges of working with real feces and to control the experimental variables, surrogate feces were used. Additional experiments with dog feces were also conducted to confirm consistent results. Dog feces were selected because it contains minimal human pathogens. Overall, this work serves as an initial investigation into the feasibility of applying this approach in a waste treatment system.

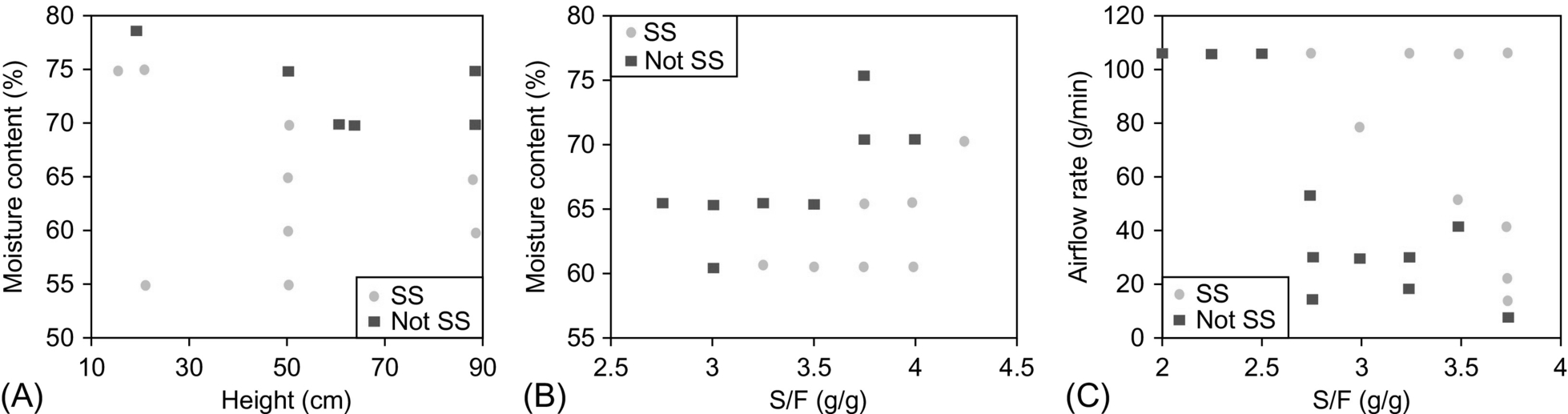

A parameter space has been mapped for conditions yielding self-sustaining smoldering of surrogate feces mixed with sand by varying moisture content, mixture pack height, airflow rate, and sand-to-fuel ratio (S/F). Results showed that the ranges of self-sustainability for each parameter are not independent; rather, they are interdependent in a complex manner. The parameter space in which a robust self-sustaining process operates was identified. Fig. 18.18 shows the interdependency of some of these parameters for the smoldering of surrogate feces mixed with sand. For example, if the moisture content of the waste is increased, then the pack height of mixture in the reactor must be shortened and the sand concentration increased. A similar situation occurs with the relationship between airflow rate and sand concentration, where higher sand concentrations allow lower airflow rates.

The smoldering performance is usually assessed in terms of smoldering propagation velocity and average temperatures. The control of the smoldering velocity is useful to determine the reactor scale and other operative conditions, while the estimation of the temperature can shade light on the potential energy recovery of the overall process. Yermán et al. studied the influence of key operational parameters on the smoldering performance (Yermán et al., 2016). A set of experiments of smoldering combustion of feces mixed with sand under a range of experimental conditions were carried out under robust and self-sustaining conditions. The parameters studied were moisture content, sand-to-feces mass ratio, sand particle size, airflow, and ignition temperature. Ignition temperature was defined as the temperature at 2 cm from the heater when the airflow is initiated.

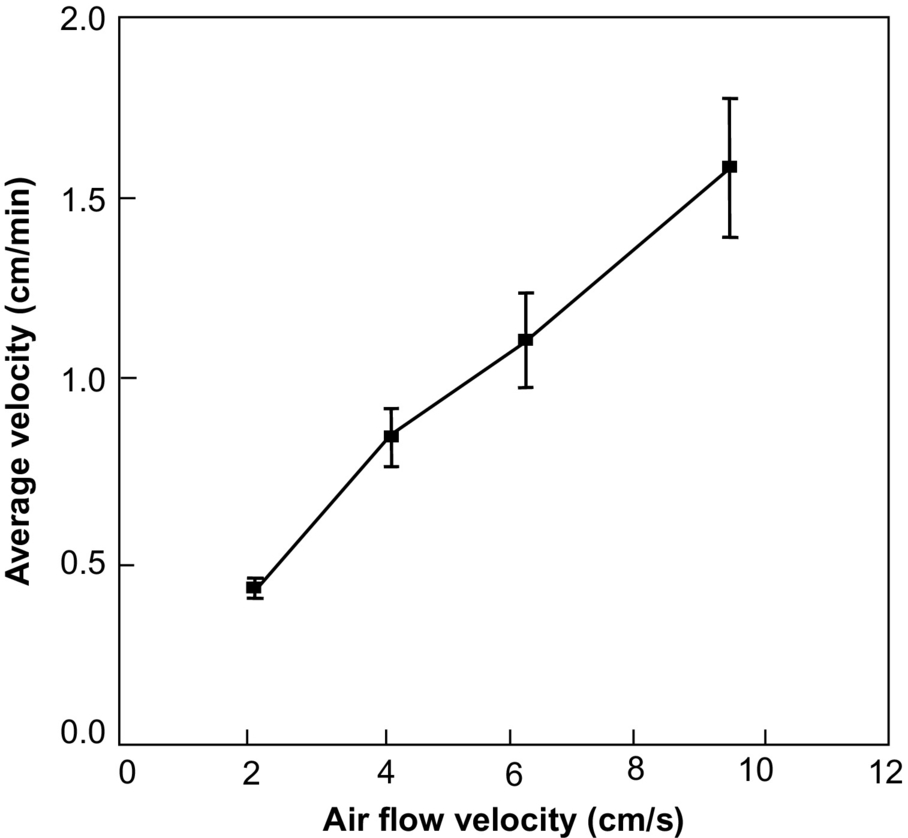

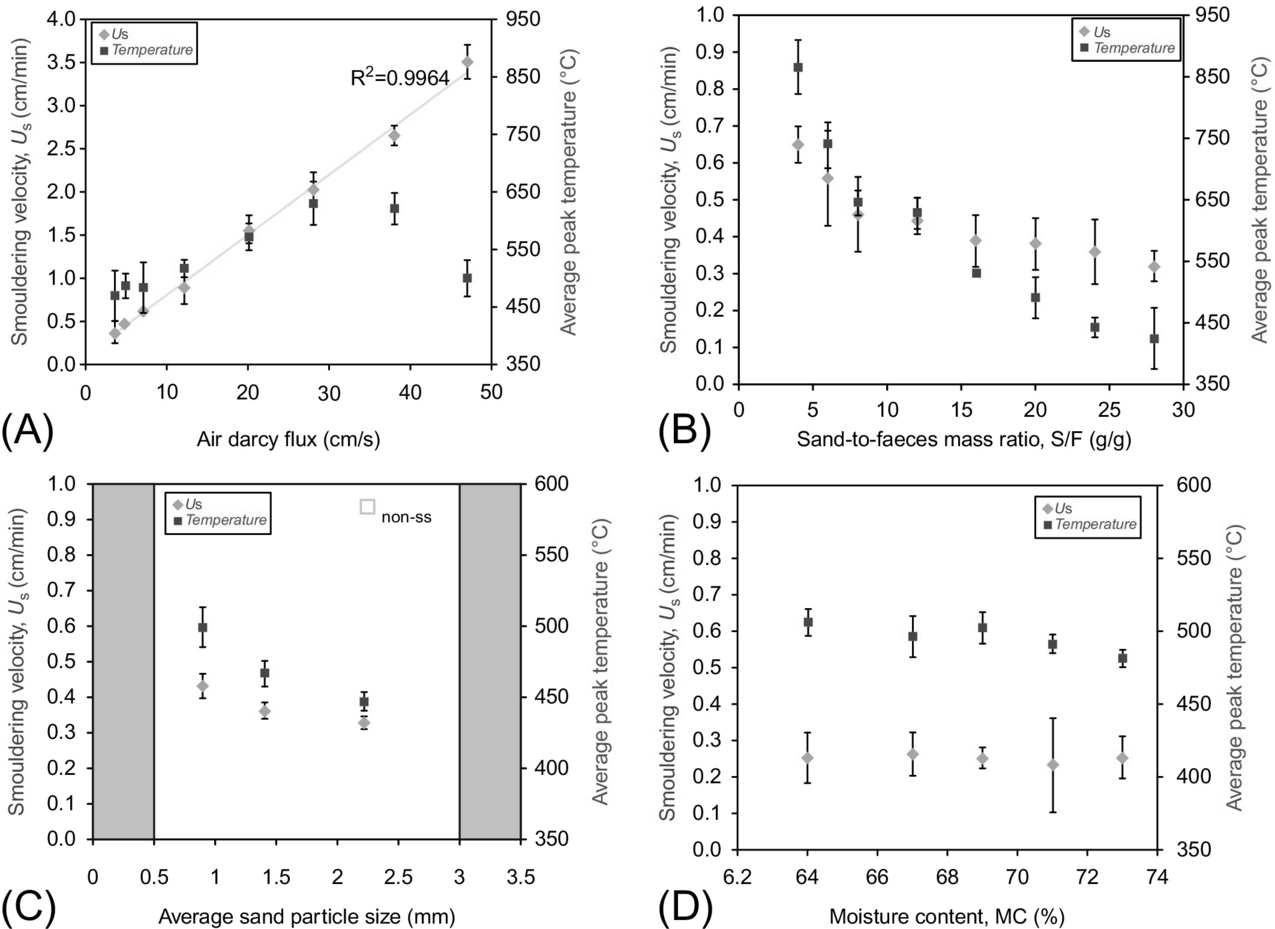

Results reveal that the airflow rate is by far the most crucial parameter affecting the smoldering velocity. Fig. 18.19A shows that there is a linear relationship between the air Darcy flux and the velocity of propagation. Therefore, the airflow can be easily utilized to modulate the smoldering velocity during the treatment process. This observation is consistent with other applications and therefore reaffirms that independent of the fuel and porous medium, airflow seems to be always the controlling parameter.

In contrast, in what regards smoldering temperatures, the relative amount of sand used appears to have the greatest impact. It was observed that by changing the sand-to-feces mass ratio, the temperatures can be modulated within a range of almost 500°C. On the other hand, the impact of this ratio on the smoldering velocity is not as great as the influence of the airflow, showing differences below 0.4 cm/s for the same range studied (Fig. 18.19B).

The sand grain size shows to have a minor effect on the smoldering temperatures and velocities (Fig. 18.19C). Nevertheless, it does have an important impact in maintaining self-sustaining smoldering. Self-sustaining smoldering was not observed for sand particle sizes below 0.5 mm or above 3.0 mm.

The moisture content in the feces acts as an energy sink and is the most crucial parameter to determine the self-sustainability of the process. Higher velocities and temperatures were registered for dried feces compared with wet (67%) feces (not shown in figure). Nevertheless, results showed that within the applicability range of moisture content for feces (65%–73%), this seems to have a minimal impact on the smoldering velocity and temperature (Fig. 18.19D). This is of fundamental importance because it confirms the observation by Kinsman et al. (2017) that smoldering will be self-sustaining if the water front is displaced ahead of the smoldering front.

18.8 Summary

The viability of using smoldering combustion as a mechanism of in situ treatment of contaminated soils has been presented. It has been shown that fuel/sand content, airflow, and fuel concentrations determine the rates of destruction of the contaminant. The role of heat losses is weak and its importance decreases with scale. Larger-scale in situ soil remediation has been proved viable but requires consideration of heterogeneities and NAPL migration. Under robust self-sustained smoldering destruction rates always exceed 98%. Self-sustained smoldering has been achieved in a robust and consistent manner at scales ranging from 0.003 to approximately 45 m3 including below the water table.