_______________________

“It’s Decline Time in America”: A Short History

Halfway into the last century, America was finished. Or so it seemed. On 4 October 1957, the Soviet Union became the first space power in history, launching its Sputnik (“satellite”) into orbit and striking terror into the American soul. This was “a shock which hit many people as hard as Pearl Harbor,” recalled a commentator for the Mutual Broadcasting System, then one of the Big Four networks. It was “a frightful blow.” America had grown “soft and complacent,” believing that it was “Number One in everything.” Yet now the country had been upstaged by its mortal rival.1

Sputnik stopped transmitting after three weeks, tumbling out of the sky two months later. Short-lived as it was, the wobbly contraption—a mere twenty-three inches across—had a devastating impact on the American psyche. Soul-searching and self-deprecation turned into a national obsession—and into a chronic reflex as the century progressed. In the midst of a crashing stock market and a deepening recession, the October surprise gave birth to a school of thought that would outlive Sputnik and regularly return to torment the American imagination all the way into the twenty-first century. Let’s call it “Declinism.”2

The basic theme—America as has-been—is recycled about every ten years. “It’s decline time in America,” the stock drama trumpets, and it is staged anew at the end of each decade—typically, as the sun is about to set on an administration while presidential candidates begin jockeying for position. As in the hand-wringing over Sputnik, the alarm does in fact spring from real trouble, be it economic hardship or military misfortune. Economically, this first wave of Declinism bears an uncanny resemblance to the last, which rose after the Crash of 2008. In the fall of 1957, the economy shrank by 4 percent; in the spring of 1958, by an appalling 10 percent. The numbers for 2008 and 2009 were minus 5 percent and minus 6 percent. So there is always a rational basis for this kind of angst attack. Just as regularly, though, anxiety expands into Spenglerian visions of foreordained decay. A crisis is not just a crisis but a portent of doom akin to the writing on the wall in the Book of Daniel. Just change names and places, and the prophecy is up to date.

Doom is one of the oldest stories of mankind. The Book of Daniel is the biblical original that has set the pattern for a rich tradition of decline and destruction in Western thought. When the “Mene, Mene, Tekel U-Pharsin”3 appears out of nowhere, Babylon’s astrologers and soothsayers—the policy experts and pollsters of that time—are flummoxed. Daniel, the captive Jewish sage has to be summoned. He quickly deciphers the eerie script on the wall. King Belshazzar and his courtiers had committed blasphemy by praying to idols. The “God in whose hand thy breath is,” Daniel informs the king, “hast thou not glorified.” Divine retribution was at hand. Belshazzar had been “weighed and found wanting.” Therefore, “God has numbered the days of your kingdom.” In that night “was Belshazzar, the king of the Chaldeans, slain.”

The modern version of this legend, retold decennially, follows the biblical model: Having gone astray, America will be called to account for the sin of pride or sloth. Like Babylon’s, its best days are over. As this is a secular saga, punishment will be handed down not by the deity but by other nations. Meaner and leaner, they will dethrone the “last best hope of earth,” to recall Lincoln’s famous words in the worst days of the Civil War. The Soviet Union was first in this tale of woe. It would be followed by Europe, Japan, India, and China. The characters changed, the drama became part of the American repertoire. Sputnik marked Decline 1.0. Versions 2.0 through 5.0 would follow.

THE 1950S: THE RUSSIANS ARE COMING!

The first in a long line of usurpers was the Soviet Union. A few months after the “Sputnik Shock,” Life magazine, then selling for a mere twenty-five cents, launched an “urgent series” titled not Mene, Mene, but “Crisis in Education.” The editorial intoned, “What has long been an ignored national problem, Sputnik has made a recognized crisis.” To drive the calamity home, the author Sloan Wilson put onstage two generic American high school graduates. One was “Johnny,” who “can’t read above fifth-grade level.” The other was “Mary,” who “has barely mastered the fourth-grade arithmetic fundamentals.” On the cusp of adulthood, this duo couldn’t even handle the three R’s. How, then, could the country face down the Soviet Union? Even gifted American children “are nowhere near as advanced in the sciences as their opposite numbers . . . in Russia.”

In a nine-page spread, the magazine laid out the “frightening scale of the problems the U.S. now faces” by contrasting the lives of two real-life students—Stephen in Chicago and Alexei in Moscow. Distracted by sports and dating, Stephen has “little time for hard study,” but for Alexei “good marks in school are literally more important than anything else in life.” The achievement gap was staggering. Though one year younger, Alexei is two years ahead of Stephen academically. While Stephen fritters away his young life with trivial pursuits, “more than half of Alexei’s classroom time is given over to scientific subjects.”4 It is hard physics over soft pleasure, with the moral all too clear: The Russians are bound to prevail.

Half a century later, a best seller by the Yale professor Amy Chua made the same point, but this time Chinese education was the model held up to America. The message of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (2011) was academic performance über alles, no play dates, no sleepovers, no TV. What Life did in 1958, the Wall Street Journal replicated fifty years later, running a short version of the book under the tell-it-all title “Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior.” It was young Alexei all over again. Compared with their Western counterparts, “Chinese parents spend approximately 10 times as long every day drilling academic activities with their children. By contrast, Western kids are more likely to participate in sports teams.”5

“This is our generation’s Sputnik moment,” intoned President Obama in his 2011 State of the Union address. Except this time it was not Soviet Russia but China and India. Otherwise, it was déjà vu all over again, to recall Yogi Berra’s malapropism. Like the Soviets, people in these two countries were “educating their children earlier and longer, with greater emphasis on math and science. They’re investing in research and new technologies.” The United States would thus have to “reach a level of research and development we haven’t seen since the height of the Space Race.”6

Back then, Time had piled on the metaphors in a cover story on the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev as its Man of the Year: “In 1957, under the orbits of a horned sphere . . . , the world’s balance of power lurched and swung toward the free world’s enemies. On any score, 1957 was a year of retreat and disarray for the West.”7 So the Soviet Union, barely industrialized and bled dry by twenty million lives lost in World War II, was poised to outgun and outproduce the United States before Stephen and Alexei would reach middle age. But that was just for starters. In fact, the crisis was much graver than Johnny’s and Mary’s shabby performance suggested. America’s very survival hung in the balance.

In the Year of the Sputnik, a presidential panel produced a top-secret report, “Deterrence and Survival in the Nuclear Age,”8 which went down in history as the Gaither Report. Though focusing on the Soviet Union, the language of doom could easily be applied to China today, the most recent challenger touted as more dynamic and disciplined than the United States. The economy of the USSR, warned the panel, is just a bit “more than one-third of that of the United States,” but “it is increasing half again as fast.” So how long would it take for the Soviet Union to demote the United States? Careening along on its straight-line projection, the report predicted that by 1980 Moscow’s annual military spending “may be double ours,” unless, of course, the United States finally woke up to the deadly threat. Today’s doomsters similarly point to the double-digit annual expansion of Chinese defense spending, and the more strident Cassandras target 2025 as the year when China will leave the United States in the dust economically. Others give the United States until 2050 to drop to second or even third place in the GDP race.

Worse, the Gaither Report claimed, the Soviets had “probably surpassed us in ICBM development”—missiles of intercontinental reach. “Probable” is another word for “don’t know,” but in the annus horribilis of 1957 the report found a grateful reader in the freshman senator from Massachusetts, John F. Kennedy. Up for reelection in 1958 and eying a presidential run two years later, he began to stoke the national angst. For him, the day of America’s disgrace was practically at hand. By 1960, “the United States will have lost . . . its superiority in nuclear striking power.” The slothful policies of President Eisenhower and his Republicans would produce “great danger within the next few years,” ran his mantra.9

This was the fabled “Missile Gap” that never existed; it would take years before Soviet missiles based at home could effectively hit the continental United States. Estimates vary widely, crediting the USSR with anything between four and thirty liquid-fueled missiles at the turn of the decade. Tanking them up would take ten hours, longer than it would take U.S. forward-based bombers to reach and destroy them. Meanwhile, the United States had amassed over three thousand strategic warheads and almost two thousand launchers by 1960. In the same year, the first missile submarine, the USS George Washington, took to the deep, where its sixteen nuclear-tipped Polaris were immune to a Soviet first strike. Whether by number or technology, the United States was far ahead of the USSR.

Facts, unfortunately, don’t deliver prophetic punch. So Kennedy painted Armageddon in the most gruesome colors. The Russians were forging ahead, and the Missile Gap would deliver to them a “new shortcut to world domination.”10 In the presidential campaign, Kennedy orated like a fully blown Declinist: “That is what we have to overcome . . . [the sense] that the United States has reached maturity, that maybe our high noon has passed, maybe our brightest days were earlier, and that now we are going into the long, slow afternoon.”11 Finis Americae was practically at hand in 1960. Henry Kissinger, then a young professor at Harvard, concurred: “Only self-delusion can keep us from admitting our decline to ourselves.”12 He would return to this theme again and again.

This was in the midst of another economic downturn, with a worst-quarter drop of 5 percent in the fall. But the United States did not ride off into the sunset, and the Soviets never managed to take that “shortcut to world domination.” A mere thirty years later, the USSR was no more, having met a fate worse than what history had supposedly reserved for the United States. It did not just decline; it literally disappeared on Christmas Day 1991, leaving behind the Russian Federation and fourteen orphan republics. Yet Kennedy’s agitation made the fictitious missile gap real enough to serve its domestic purpose. He kept his Senate seat in 1958 and beat Richard Nixon to the White House two years later.

Ten years later, at the end of the Kennedy-Johnson era, the drama of decline was reenacted once again, this time by Kennedy’s Republican disciple Richard M. Nixon, when he was mounting his second run for the White House. Except that this time the story was not about a fictitious missile gap but about a real war in Vietnam, a campaign that originated in hubris and ended in tragedy. Somebody had to lead America out of desolation, just as Kennedy had promised a decade earlier. This time, the story came with a new twist.

THE 1960S: THE “UNRAVELING OF AMERICA”

As always, pride goeth before the fall. Pummeled by Sputnik and oppressed by the nightmare of Soviet superiority, America’s spirits would soon soar again. Only a handful of years after Sputnik, America was No. 1 again, having reduced its mortal rival to a distant second in the stylized passage of arms that was the Cuban Missile Crisis in the fall of 1962.

All narratives of national decline turn on the nature of power: who is losing, who is gaining it? In the traditional great-power world of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, war was the truest measure, delivering swift and conclusive verdicts. It took upstart Prussia just ten months to demote mighty France to a has-been in the War of 1870–71. In 1967, Israel routed all three of its neighbors—Egypt, Syria, and Jordan—in less than a week, establishing itself as a regional superpower. In the nuclear age, however, war can no longer serve as a test of strength. Overkill has eliminated great-power war from the repertoire, and so crises have become the yardstick of power. The most dangerous and decisive one was the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Kennedy had been in office for less than two years.

The outcome proved how empty Kennedy’s doomsday rhetoric had been, and how frenzied the alarm over Moscow’s unstoppable rise. America was back on top—and triumphant, to boot. By taking on the United States on its home turf, the Soviets actually proved that the Missile Gap was in fact their problem. Why else move up so close to the American mainland, engineering a threat that risked devastating preemption against the Soviet homeland? The naval confrontation in the Caribbean waters did not last long—thirteen days, to be exact. Kennedy prevailed, and Nikita Khrushchev, Russia’s ruler, had to pledge withdrawal. He would later pay with his political life for his “adventurism,” as his Politburo colleagues called the Cuban gambit. America’s strategic and conventional superiority had carried the day, in a flash that revealed the true distribution of power, and without a shot being fired.

Freshly vindicated, America was again safe and sound. The temptation wasn’t long in coming. Hubris followed triumph as night follows day, notably in Vietnam, where Kennedy, flush with victory, sent some sixteen thousand American servicemen as advisers. By mid-decade, his successor Lyndon B. Johnson had dispatched half a million combat troops. At the end of the 1960s, the war was not going well, though much worse at home than in the Asian theater. Many years later, Harvey Mansfield, a political philosopher at Harvard, would describe the Vietnam years as “comprehensive disaster.”13 This time, the calamity was for real, not a deliberate dramatization, as in the Sputnik years.

It was war in Vietnam and war at home, a crumbling dollar and rising inflation, burning cities and generational revolt. It was the longest and darkest chapter in the history of American self-doubt. Lyndon B. Johnson thought he could do it all—the War on Poverty and the war against Ho Chi Minh, but without raising taxes, let alone reining in civilian spending, which actually climbed to new heights. He told his biographer, “I was determined to be a leader of war and a leader of peace. I wanted both, I believed in both, and I believed America had the resources to provide for both.”14 Although the mightiest nation on earth, America did not.

Jerry Rubin, the counterculture hero and leading Yippie, who in a very American career would morph into a wealthy entrepreneur in the 1980s, wrote on the country’s wall (note the German spelling to evoke the Nazi parallel),

The war against Amerika

In the schools

And the streets

By white middle-class kids

Thus commenced.15

In 1966, the demonstrators marched by the thousands. By April 1967, some 400,000 thronged through New York; in October, 100,000 massed at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington. One year later, Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered, and so was John F. Kennedy’s brother Robert. It was “the unraveling of America,” as the title of a book on the period had it, or more ominously, “America’s suicide attempt.”16 Vietnam was to Sputnik what viral pneumonia is to a hiccup. Running for the Democratic nomination in 1968, Robert Kennedy naturally invoked the classic prophetic motifs of transgression and perdition: Guilty were those “who have removed themselves from the American tradition, from . . . the soul of our nation.” It was a “failure of national purpose,” which stemmed not just from bad policies but from the “darker impulses of the American spirit.”17 Thus spoke Daniel to King Lyndon.

Robert Kennedy was not alone in uttering such sentiments. Richard Nixon, the Republican, was also running for the presidency. Like JFK exactly a decade earlier, he sounded the alarm over America’s fall from grace. “Let us look at the balance of power in the world,” he orated in 1967:

Twenty years ago the United States had a monopoly on the atomic bomb and our military superiority was unquestioned. Even five years ago our advantage was still decisive. Today the Soviet Union may be ahead of us in megaton capacity and will have missile parity with the United States by 1970. Communist China within five years will have a significant deliverable nuclear capability.

Finally, let us look at American prestige:

Twenty years ago . . . we were respected throughout the world. Today, hardly a day goes by when our flag is not spit upon, a library burned, an embassy stoned some place in the world. In fact, you don’t have to leave the United States to find examples.18

This was Declinism Lite—not the end, but the shrinking of America in terms of global power and prestige. The theme would resurface through the decades. America was sinking slowly, while others were rising; its influence was on the wane. This would become the leitmotif of the Nixon administration, and it foreshadowed the “rise of the rest” that suffuses the present-day celebration of China, India, et al. Its fullest expression was a rambling speech by the president in Kansas City in 1971.

America is no longer the economic “number one,” Nixon decreed. There are in fact “five great power centers in the world today.” These are the United States, followed by Western Europe, a “resurgent Japan,” the Soviet Union, and “Mainland China,” which “inevitably” is growing into “an enormous economic power” and eventually a global strategic player. “So, in sum, what do we see . . . as we look ahead 5 years, 10 years, perhaps it is 15? We see five great economic super powers.”

The diagnosis didn’t quite pan out. Fifteen years later, in 1986, Japan was about to peak. At the end of the decade, it was sliding into long-term stagnation whose end we have yet to see. The Soviet Union was sinking even more rapidly, its empire collapsing shortly thereafter. But at the end of his speech, Nixon sounded like Oswald Spengler and Arnold Toynbee, the twentieth century’s most famous Declinists, rolled into one.19 “I think of what happened to Greece and to Rome . . . , great civilizations of the past,” which first became wealthy, then “lost their will to live, to improve.” So they succumbed to the “decadence which eventually destroys a civilization.” And “the United States is now reaching that period.”

This was the buildup. Like any good prophet, Nixon concluded by switching from doom to deliverance. America’s fall from grace was not yet, he told his audience; the country was still “preeminent” as “world leader.” It had the “vitality,” the “courage,” the “destiny to play a great role,” but the “people need to be reassured.” 20 Like all prophets, the president was the man to do so; “trust me,” so to speak. Henry Kissinger, who had been tutoring Nixon in foreign policy, did not sound quite as sanguine.

For Nixon’s national security adviser, the end of the two-superpower world was already here, and America had to adjust to the new reality. “Political multipolarity” was at hand, he wrote in 1968, which “makes it impossible to impose an American design.”21 The nation, in other words, had to scale back. In yesterday’s two-power world, the United States had held at least one-half of the voting stock; in this new five-power world, that share was bound to dwindle to one-fifth.

This prospect apparently gave rise to melancholy reflections. According to the retired navy chief Elmo Zumwalt, Kissinger had confided to him in 1970 that the United States had “passed its historical high point like so many earlier civilizations.” Thus, it was Kissinger’s job to “persuade the Russians to give us the best deal we can get, recognizing that the historical forces favor them.” Americans “lack the stamina to stay the course against the Russians,” Zumwalt quoted Kissinger as saying; they are “ ‘Sparta’ to our ‘Athens.’ ” Kissinger would later denounce the report as total “fabrication,” adding that Zumwalt had “misunderstood the points I was making.”22

Given his political agenda, the admiral surely did misrepresent the conversation. A Democrat running for the Senate in Virginia in 1976, Zumwalt may have used Kissinger as a whipping boy in order to discredit Nixon’s foreign policy. On the other hand, Nixon’s and Kissinger’s perorations weren’t pulled from thin air. The United States was hemorrhaging blood, treasure, and reputation. The Vietnam War could not be sustained at home; a wounded nation, the United States had to move out of harm’s way. Declinism—heartfelt or instrumental—was the way to prepare the nation for the coming U-turn in grand strategy. This could have been the larger purpose of the “we are down, and they are up” oratory.

The new strategy was détente with the Soviet Union and the “opening” toward China, the two powers that were arming and abetting North Vietnam. Rapprochement with the two Red giants would give the United States leverage over Hanoi. But how to persuade a nation that had been weaned since the late 1940s on a steady diet of “godless communism”? To legitimate the new diplomacy, a new domestic consensus had to be forged. And the issue was “whether the new balance which the Administration sought abroad would balance at home.”23

So the quintessential Cold Warrior, Richard Nixon, had to change stripes. He had to persuade the nation to scale back, especially since Congress would no longer support this or any other imperial venture. The United States could not play the world’s policeman; it had to bring high-flying ends in line with dwindling means. Hence it was high time to avoid direct involvement in favor of regional power balances. Let the locals carry the burden. This was the gist of the new Nixon Doctrine.24 In order to justify downsizing and dealing with yesterday’s mortal foes, it might help to paint the nation smaller than it was. Declinism, as always, was an educational exercise.

Did Nixon and Kissinger intend to vacate America’s exalted place at the top? The “China opening” and détente with Moscow actually added up to a classic of realpolitik, in which deft diplomacy compensated for an apparent or genuine loss of power in these trying days. With America in the middle, Washington would play the Soviets against the Chinese, and both against North Vietnam. In either case, the United States would act as the concertmaster.

Alas, neither China nor Soviet Russia would play second fiddle to the United States in East Asia. They kept on arming and shielding North Vietnam, and Ho Chi Minh went on to conquer the South after the United States had ended its direct military involvement in 1972. Five years later, just before leaving office, Henry Kissinger harked back to his 1968 article about adapting to “political multipolarity,” ending on a melancholy note: “In the nature of things, this task could not have been completed—even without Watergate.”25 But if by “this task” Kissinger meant transforming the world into a pentagon of power, with the United States voluntarily sinking to primus inter pares, the project was neither necessary nor part of the plan.

The United States, though it did not prevail in Vietnam, was hardly facing decline in the late 1960s. It did suffer from the revolt of the young, from a crisis of the spirit, and the plight of an economy charged with producing too many guns and too much butter (aka social spending) all at once. But by any measure of power—economic mass, military clout, and diplomatic weight—the United States remained preeminent. Those fabled “dominoes” didn’t fall across the length and breadth of Asia; North Vietnam’s conquest of the South was socialism in just one more half country.26 Losing a war without having to suffer strategic demotion—this is the mark of a truly great power. Lesser powers have not been so lucky. After its mauling by Prussia-Germany in 1871, France could no longer claim strategic primacy on the Continent. After 1945, it was Germany’s turn to fall from power. After the Soviet Union lost the Cold War, it disintegrated. Defeat spelled disaster for all of them.

THE 1970S: AMERICA’S “MALAISE”

At the end of the 1970s, real calamity struck once again. After the second oil shock, in 1979, gasoline prices in the United States almost doubled in twelve months, a rise that took ten years to work itself out in the first decade of the twenty-first century. By the summer of 1979, Americans again faced long gas lines at the pump, as they had during the first oil shock, in 1973, when price controls, as they always do, led to infuriating shortages. Inflation kept accelerating: from 6 percent in 1977, when Jimmy Carter took office, to 11 percent in 1979. It peaked at almost 14 percent in the election year of 1980. Two years later, U.S. unemployment shot up to almost 11 percent—the highest level since the Great Depression, and more than one percentage point higher than at the worst moment of the 2007–09 recession. At the end of the 1980s, a dollar was worth less than half of what it was worth at the beginning. Abroad, the dollar had dropped likewise against major European currencies, like the deutsche mark. In contrast to those of the Carter years, the economic woes of the Obama years looked more like a nasty migraine—painful and protracted, but not deadly.

The contrast sharpens when the political humiliations of the time are added to economic catastrophe. Nicaragua fell to the Sandinistas in 1979, becoming Cuba’s first Latin American satellite. The Shah, America’s longtime pillar in the Middle East, escaped for his life from the Khomeini Revolution in January 1979. And this time, the CIA and Britain’s MI-6 could no longer engineer a coup to bring him back, as they had done in 1953. Iranian students occupied the U.S. embassy in Tehran, terrorizing their American hostages for 444 days. A halfhearted attempt by the Carter administration to rescue them ended in the bloody disaster of Desert One, forcing the abortion of the mission. Soviet and Cuban forces were marching across resource-rich Central Africa. Finally, during Christmas 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan.

Nothing could underscore America’s fragility more than Jimmy Carter’s famous “Malaise Speech” of 1979, as the media would dub it. He diagnosed “a crisis of confidence . . . that strikes at the very heart and soul and spirit of our national will. We can see this crisis in the growing doubt about the meaning of our own lives and in the loss of a unity of purpose for our Nation.” That “erosion of our confidence” threatens to “destroy the social and the political fabric of America.” It all added up to an assault on our “heart, soul, spirit, and will.”27 No other American president has ever painted the country’s fall from grace in such gruesome colors.

At the end of the year, Declinism was rampant throughout the land. Newsweek ran a cover story titled “Has the U.S. Lost Its Clout?” The magazine had unearthed proof positive of the “erosion of American prestige and power.” There was the Soviet bogey again. Once America had held a nuclear monopoly; now it was struggling “to maintain something called ‘parity.’ ” The country was “slipping.” To prove the point, Newsweek trundled out a Japanese professor who had always been “eager” to travel to the United States, but now he didn’t “even want to go again this year.” The spokesman of the German government wouldn’t exactly gloat; “rather we feel pity” for the United States—schadenfreude masking as solicitous concern. A French analyst did not see the “American way of life” as “so absolutely superior” any more.28 Adjust the names and the dates, and you have a one-size-fits-all-decades diagnosis of inescapable decline.

In an acrid review of the Nixon-Carter era, Robert W. Tucker of Johns Hopkins wrote, “Though disputed until recently,” America’s “decline” was “no longer a matter of serious contention.” Following the ancient prophetic tradition, which sees perdition as the wages of sin, the noted scholar brandished the “unpalatable truth that we have betrayed ourselves.”29 America wasn’t quite finished, opined Helmut Sonnenfeldt, previously Kissinger’s counselor in the State Department. But the “American dream . . . needs a good deal of revision. We can do less than we have tended to think.” Winston Lord, another former aide, put it tout court in his new role as the head of the Council on Foreign Relations, which in those days served as unofficial central committee of the U.S. foreign policy establishment: “Our era of predominance is over.”30

The great riser was again the Soviet Union. Could Missile Gap II be far behind? Henry Kissinger, now out of office, warned that America’s strategic “superiority has eroded.” If the country did not get back into the race, “then in the ’80s we’re going to pay a very serious price. The first installments are already visible.”31 The sequel of the first Missile Gap was called “Window of Vulnerability,” and the script was written not by an aspiring presidential candidate, as in Kennedy’s case, but by the Committee on the Present Danger. This was an assembly of influential private personages, which had already played Cassandra in 1950 and was rising to renewed prominence in the Carter years.32 Ronald Reagan, the Republican candidate in 1980, had joined the executive board of the committee a year earlier.

Again, Declinism came with real decline. The 1980–82 recession saw the worst single-quarter plunge—almost 8 percent of GDP—since the Great Depression. The Window of Vulnerability built on previous doomsday scenarios that had painted the United States as prey-to-be of the Soviet bear. These were the Gaither Report of 1957 and the National Security Council’s NSC-68 memorandum of 1950. The latter, an in-house document, had spelled out to President Truman: Rearm or retreat! Now, thirty years later, the Soviet Union was again reaching for nuclear superiority, and this time for keeps. Or so the Declinist agitation had it. The Soviets were arming to fight and win a nuclear war, the Committee on the Present Danger trumpeted. While hardening their own silos, the Soviets were building heavier and more accurate missiles capable of taking out America’s retaliatory force in a first strike.

This scenario was hyperbole verging on irreality, given that the Soviet Union could not take out America’s undersea strike force or those bombers that were on constant airborne readiness. For Newsweek, however, this was “the most alarming forecast in years.”33 Time brought onstage defense experts who warned that the “Soviets are ahead or gaining in almost every category.”34 An “even more menacing prospect is a shift in the world balance of power toward the Soviet Union,” Time wrote on America’s wall two years later.35 The columnist Joseph Alsop, reaching deeply into his grab bag of gloom, placed America right next to ancient Carthage, which was destroyed by “Rome’s warlike manpower.” Russia was Rome, and “we have reached the stage when we must expect disaster in the long run, unless we make painful efforts to redress the balance without undue delay.”36

That alarm, which had been sounded twice in the 1950s, turned out to be false once more. At the time, the United States had almost three times as many strategic warheads as the Soviet Union. But as myth, the Window of Vulnerability was as effective as its predecessors—NSC-68 and the Gaither Report. It triggered a wave of rearmament in the latter days of the Carter administration, and the tide rose mightily under Reagan.

Reagan was the greatest profiteer of the Declinist agitation. He appropriated the panicky language as deftly as had John F. Kennedy, the Democrat, twenty years before. “Mr. Carter,” Reagan recited in the presidential debate of 1980, “had canceled the B-I bomber, delayed the MX [missile], delayed the Trident submarine, delayed the cruise missile, shut down . . . the Minuteman missile production line. . . .” In other words, his rival was guilty of sloth and neglect. It was high time “to restore our margin of safety” and to stop “unilateral concessions” to the Soviets.37

“America’s defense strength,” remonstrated Reagan, “is at its lowest ebb in a generation, while the Soviet Union is vastly outspending us in both strategic and conventional arms.”38 The Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington summed it all up: “Feelings of decline and malaise, reinforced by another oil price hike and inflation, generated the political currents that brought Ronald Reagan to power in 1981.”39 With the American hostages still held in Iran, Carter lost in a landslide. And true to the prophetic tradition—first Jeremiah, then redeemer—Reagan’s most famous campaign commercial three years later intoned, “It’s morning again in America. And under the leadership of President Reagan, our country is prouder and stronger and better.”40 But not for long.

THE 1980S: JAPAN’S “RISING SUN”

In previous decades—from Sputnik to “Malaise”—candidates and committees had crowded the stage where the stock drama “Decline Time in America” was played out. The 1980s belonged to the academics, analysts, and thriller authors. The starring role also changed. After three decades of “The Russians Are Coming,” the Soviet Union was faltering, and it would go on to lose the Cold War in 1989, when the “Velvet Revolutions” swept away Moscow’s decayed empire in Eastern Europe. So who would push aside the United States now? Enter Japan in the lead and Europe in a supporting role.

Japan had been fingered as a power to watch since the early 1970s, in a language almost identical to the hoopla about China three decades later:

Of all the various postwar economic miracles, the Japanese is the most spectacular. Japan . . . has become, in less than a quarter century, the free world’s second-ranking industrial power. Since 1950, Japan’s GNP has grown an average of 10 percent per year. From 1960 to 1969, it rose at an . . . average of 11.4 percent per year . . . The Japanese GNP [might catch] up with the American by 1985 or 1990. The year 2000 . . . will begin the “Japanese century.”41

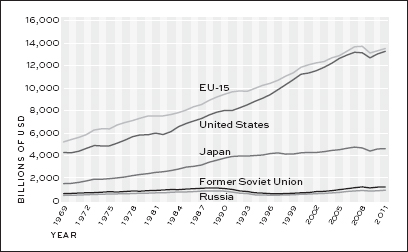

Percentages are destiny, this classic of Declinism suggested, and with growth numbers that dwarfed even China’s performance (around 10 percent) a generation later. Japan was soaring, now and forever more. So first a reality check on the trends as they actually unfolded. In 1985, when Japan was supposed to overtake the United States, its GDP was $1.3 trillion (in then dollars); the United States’ was $4.2 trillion, three times larger. Five years later—this was the next predicted draw-even point—the tally was 3 trillion vs. 6 trillion; so Japan was coming closer. In 2000, it was 4.6 trillion vs. 10 trillion; so Japan was evidently slowing. Now shift forward to the present, and it is back to the future and to the original three-to-one gap.42 In real dollars, the gap was even larger (see figure 1). Such is the fate of linear, tomorrow-will-be-like-yesterday projections.

1. Real GDP, 1969–2011 (2005 U.S. dollars)

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/macroeconomics/Data/HistoricalRealGDPValues.xls.

Yet linearity—the idea of Japan’s unbroken rise—would feed Declinism for the next twenty years. Among the first to turn the “Japan über alles” theme song into a long dirge for America was the Harvard sociologist Ezra Vogel with his Japan as Number One: Lessons for America. This was in 1979, at the height of Jimmy Carter’s “malaise,” and it set the tone for unending hero worship. For its admirers, Japan was Hercules and Einstein rolled into one. This giant’s strengths and brains were superhuman, as China’s are said to be today.

The choice narrative unfolded like this: Japan’s bureaucracy planned with meticulous foresight. These wise samurai knew everything, and what they did not know, they studied obsessively to unearth. Government and business worked hand in glove for the greater glory of the nation. Japanese firms could draw on limitless capital, and because the funds were provided by bank loans, not by equity, corporations did not have to please shortsighted stockholders. The educational system was celebrated as the Soviet one had been in the Sputnik days, and as China’s is today: no nonsense, hard work, ruthless competition to promote the best and the brightest. Even better, Japan shared none of America’s pathologies. Its crime rate was minuscule; its cities were clean and safe. Vogel’s Japan as Number One, noted an admiring reviewer, was a monument to “Japan’s steamroller eminence.”43

Another typical paean was sung by Time: Japan’s “power elite practices a democratic ideal” that Americans ignore: “the spirit of compromise and consensus.” Business and government are not adversaries; they “work together.” State-owned banks make “low-interest loans to manufacturers,” and private banks “know that the government expects them, too, to give easy credits.” The government does not yield “to the pleas of special interest groups.” Bureaucrats and executives jointly manage policy. The two sides “understand one another . . . because these leaders usually have the same roots of culture and class.”44 Hence a culture as messy and self-absorbed as the American one could never live up to such perfection. Today’s China admirers use similar language when praising the advantages of “authoritarian modernization.”

American admiration for this No. 1 soon degenerated into sheer paranoia that would oppress the American imagination for years on end. In 1992, Michael Crichton published the best seller Rising Sun, which was made into a movie with Sean Connery and Wesley Snipes one year later, grossing $15 million ($24 million today) on the first weekend. It was a perfect testimony to America’s dread of Japan, the China of the 1980s.

During World War II, the Japanese had never made it beyond Pearl Harbor; over the next three years, its Asian empire was shattered by America’s military machine. But in the 1980s Japan looked truly indomitable. It was amassing not just a regional but also a global empire—peacefully and with beachheads right in the heart of the American economy. In 1989, Mitsubishi bought one national treasure, New York’s Rockefeller Center; one year later, a Japanese businessman grabbed another, Pebble Beach in California. Fear and loathing exploded in a famous scene in Congress in 1987, where a Japanese VCR was smashed in front of the cameras to make the point.

Rising Sun, the movie, would gross $60 million ($100 million current). On the surface, the book and the movie were spinning a gripping whodunit. But the real message was a remake of Daniel’s deadly prophecy. Like Babylon’s, America’s days were numbered. The plot: A young woman is raped and murdered during the grand opening of a Japanese company headquarters in Los Angeles. In short order, though, the chief of police orders the two detectives to drop the investigation. So the Japanese, the plot whispers, had already corrupted a mighty American city. Undeterred, the intrepid duo goes on to uncover a wider conspiracy: The Japanese want control over the U.S. electronics industry, but only for starters; the ultimate stake is political power. So the invaders try to pin the murder on an anti-Japanese senator who is mulling a presidential run. In the end, the righteous sleuths confront the real culprit, a Japanese executive, with the damning evidence. He meets his just deserts by jumping to his death, and America is saved.

The off-camera realities should have been more heartening still. At the peak of the paranoia, the Japanese economy was in free fall as well, plunging into the “Lost Decade” of the 1990s—into contraction and deflation. Yet nobody noticed how Japan’s economic miracle was evaporating. In an afterword to Rising Sun, the author Michael Crichton insisted that the United States still had to “come to grips with the fact that Japan has become the leading industrial nation.” It had “invented a new kind of trade—adversarial trade, trade like war.” In Debt of Honor of 1994, the thriller author Tom Clancy went to the summit of all fears, laying out a U.S.-Japanese trade war escalating into the real thing with a nuclear-armed Japan. This movie was a blockbuster as well.

Lovers of irony might have a field day by comparing the fiction with the figures. While Crichton and Clancy were profiting handsomely from their nightmare tales, Japan was sinking fast. The country had boasted double-digit growth rates in the 1950s and 1960s, which at several points had exceeded the 10 percent of China’s a generation later. Double-digit expansion ended in 1970. At the close of the 1970s, growth was down to less than 3 percent. In the 1980s, the Japanese economy oscillated between a low of 2 percent and a high of 7 percent. Growth peaked in 1988, the year that marked the beginning of a relentless slide. Yet in the same year, Clyde Prestowitz, formerly assistant secretary of commerce in the Reagan administration, predicted, “The American century is over. The big development in the latter part of the century is the emergence of Japan as a major superpower.”45 The United States was a Japanese “colony in the making.”46

In fact, it was downhill for the colonizer. In 1992, the year of the Rising Sun, growth nosedived below 1 percent, and in 1994, when Debt of Honor came out, the rate was lower still. The “Lost Decade,” with two dips below zero, was in full swing. Ever since, Japan has been growing at about half the American rate.47 As Japan’s economy worsened, so did its press; this is how the nimble-footed media work. Shiny pillars of excellence suddenly crumbled into piles of rot. The politicians? Poodles of entrenched interests, incompetent and self-serving. The administration? “Japan’s bureaucratically guided capitalism . . . demonstrates an increasing propensity to corruption.” The banking system that once gushed forth limitless capital? “It is mired in bad debt and cover-up.”48 The school system? An inhuman pressure cooker that is good for rote learning, but flunks on fresh thinking.

Though shalt not mistake a rapid rise from a low base for an everlasting boom was the lesson of the 1980s, which also applied to East Asia’s other shooting stars. Japan’s economic miracle resembled South Korea’s, Taiwan’s, and today’s China’s (for the parallels, see chapters 4 and 5). Throw in the catch-up economy of Germany, as well, laid low just as Japan’s was in World War II—different cultures, similar paths of redevelopment. The steep rise of Japan et al. was fed from the outside by exports and at home by underconsumption and its flip side, high saving.

The surpluses in the trade and savings accounts made money extraordinarily cheap. Funds became even more plentiful as a rising yen swept in foreign monies in search of easy profits from further revaluation. This will happen in China, too, if the country unfetters its currency and keeps it free-floating. The predictable result in Japan was explosive asset inflation (which is already biting in China today). The Nikkei index hit an all-time high of almost 39,000 on 29 December 1989. Choice properties in Tokyo sold at $1.5 million per square meter (or $180,000 per square foot in current dollars). When the bubble burst, trillions were wiped out in the collapse of the stock and real estate markets. Twenty years later, the Nikkei was creeping along below the 10,000 mark.

The year of the Rising Sun was good for yet another object lesson. In the United States, 1992 marked the birth of the longest expansion since the mid-nineteenth century, when reliable statistics became available.49 Essentially, it lasted until 2007, the year before the crash. The boom was interrupted only briefly by an eight-month stumble below 1 percent growth in 2001. That was in the aftermath of the “dot-com bubble” pricked in March 2000.

The Declinists were not impressed.

Just five years before America’s fifteen-year boom, the Johns Hopkins academic David Calleo had called the United States a “hegemon in decay.” It was “set on a course that points to an ignominious end,” he predicted.50 Now, at the threshold of America’s fabulous long run, the scholar devoted an entire chapter of The Bankrupting of America to “Decline Revisited.” Why another round of gloom? His answer was “de-industrialization.” It occupies a place of honor in the Hall of Declinism, next to the theories of many other authors who argued that “making stuff” beats inventing and designing, moving and marketing, trading and banking. “Most of the new service jobs” were not in high-tech or high value-added, Calleo claimed, but “in fast-food chains, discount retail stores . . . and similar low-wage sectors.”51

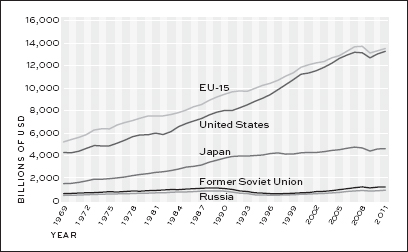

In short, America’s best days were over—again. It was evolving into a land of hamburger flippers, pizza boys, and big-box retail clerks. In fact the opposite was true; the majority of new jobs were adding value above average. The simplest and best measure of value creation is “real GDP per worker.” In the past fifty years, the United States has consistently outranked its nearest competitors, including Japan and Germany, by impressive margins, as is shown in figure 2.52

2. Real GDP per Employed Person (2010 U.S. dollars)

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Division of International Labor Comparisons, 15 August 2011.53

Another favorite of 1980s-style Declinism was Western Europe. In 1987, Calleo and other admirers of the Old Continent thought that the European Community was poised to outstrip the “hegemon in decay.” The United States was “no longer supreme.” Its edge gone, the United States was floundering amid great dangers. “If there is a way out, it lies through Europe. History has come full circle: the Old World is needed to restore balance to the New.”54 The problem with America was too much military spending, an “undisciplined budget,” “financial disorder,” a glaring lack of “creative investment.” How much better positioned were the Europeans with their “stable policies favorable to business investment”! Hence America should draw “inspiration” from Western Europe. With its healthier economy, the half continent was moving toward a more perfect union. To boot, its governments were “more efficient than the American.”55

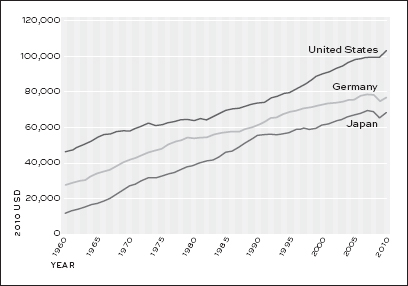

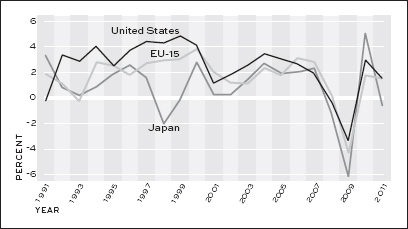

The problem with this assessment was that in the 1990s the United States would grow at an annual average of 3.5 percent and Europe (EU-15) by less than 2 percent (see figure 3). By the time the decade was over, unemployment in the United States had fallen to below 4 percent, which is defined as full-employment. In the EU-15, it stood at 9 percent. So much for the End of Work, a stew of Malthus and Marx, cooked up at the time by Jeremy Rifkin. As his book had it, the entire globe would soon run out of jobs because of automation and information technology.56 The United States stubbornly refused to obey what was offered as an iron law of history. So did the Asian economies.

3. Real GDP Growth Rates, 1991–2011

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, “Historical GDP and Growth Rates,” http://www.ers.usda.gov/Data/Macroeconomics/Data/HistoricalRealGDPValues.xls.

The preeminent Declinist of the 1980s was Paul Kennedy, the Yale historian, who published The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers in 1987. The central argument of the 700-page tome was this: “The United States now runs the risk, so familiar to historians, of the rise and fall of previous Great Powers, of . . . ‘imperial overstretch.’ ” Overstretch meant “that the sum total of the United States’ global interests and obligations is . . . far larger than the country’s power to defend them all simultaneously.”57 In an op-ed version, Kennedy provided this checklist of decay: “overall growth lagging behind that of its chief rivals,” the “social problems of its inner cities,” the “eroding infrastructure,” and the “shortcomings of its educational system.” It all added up to “relative decline,” just as in the case of Britain, which once was also No. 1. Now the “new number one power is faltering.”58

History had spoken, and there was only one decent choice left for the about-to-be-defrocked superpower: to “manage” its affairs so that the “erosion” progressed “slowly and smoothly.”59 Get your house in order, cut back on profligacy and imperial ambitions, counseled this former Briton. The most trenchant critique of Kennedy’s Declinism was Samuel Huntington’s seminal Foreign Affairs article in 1988.60 He reserved his sharpest attack for a classic of Declinism: the steady shrinkage of America’s share of the global economy. To lose GDP was to lose greatness, was the gist of Kennedy’s indictment.

But it all depends on how the numbers are parsed. If 1945 is the base line, the United States was indeed on the skids. At the end of history’s most murderous war, the American share of the global economy is commonly estimated at one-half. Naturally, as Europe, Japan, and the Soviet Union recuperated, that abnormal take was bound to shrink.61 By 1950, the weight of the American economy was down to 27 percent, which is still enormous when compared with another baseline: the eve of World War I. At that point, the United States was good for only one-fifth of the world’s total. In the 1970s, the average share was nearly 27 percent and at the end of the naughts of the twenty-first century a bit more than 26 percent.62 The data demonstrate obstinate continuity once the anomaly of post-1945 is ignored.

The more general problem lurked elsewhere. When Kennedy looked at the two nations at the top, the United States and the USSR, he discovered a kind of “competitive decadence,” a term coined by the Sovietologist Leopold Labedz some forty years ago. Both were declining, but the United States was sinking faster, Kennedy concluded. Actually, it was the other way around. The Soviet/former Soviet share halved between the 1970s and the 1990s, which is an enormous plunge by any historical standard. Kennedy certainly did not think the Soviet Union would “collapse at the first serious testing”63—very few people thought so64—but collapse the USSR did, a mere four years after The Rise and Fall came out. And why? Because whatever symptoms of decadence the United States displayed, the Soviet Union had them in multiples. Kennedy had so much right, except for the name of the loser.

Muscovy was overstretched. It had to police and subsidize its impoverished East European empire. It had to keep afloat its Latin American satrapy in Cuba, and pay for Castro’s advance guard in the heart of Africa. It was fighting an unwinnable war in Afghanistan. It spent anywhere from two to three times more on its military (as a share of a much smaller economy) than did the United States, straining under the added burden of keeping up with Reaganite arms racing. Totalitarian industrialization under Stalin had brought victory over Nazi Germany. Now the model was grinding to a halt, colliding at every step with the demands of a modern economy. The Soviet Union lacked capital markets and capitalists; it stifled competition and globalization—conditions abounding in the United States. Worse, the Soviet Union suffered from cultural pathologies that made the United States look like an exemplar of strapping health. The list was endless, ranging from alcoholism as a national disease via plummeting fertility rates to the lowest life expectancy in the developed world.

The Soviet Union was the proverbial time bomb waiting to explode. The trigger was the price of oil. In 1980, crude fetched $100 per barrel (all figures in 2012 dollars). When Mikhail Gorbachev was anointed as general secretary five years later, oil stood at $57. When the Soviet Union committed suicide by abolishing itself on Christmas Day 1991, oil sold for $37, dropping to its lowest low, $17, seven years later. At that point, oil was cheaper in real terms than it had been just before the first oil shock, in 1973.65 This “Upper-Volta with nuclear weapons,” as the German chancellor Helmut Schmidt liked to quip, was in effect a Third World extraction economy chained to the prices of raw materials, especially of oil and gas. The source of its power had been minerals and nukes, as the long slide after Gorbachev’s rise demonstrated.

Russia was more like Habsburg without Latin American gold and silver, which had paid for an empire “on which the sun never sets” until it ran out. Or like the Ottoman Empire, once a formidable war machine that drove all the way to Bosnia in the west and Basra in the east, but proved immune to modernization. And so the Soviet Empire was not at all like the United States. It did not possess the countless “renewable energies” of an economy that was the world’s largest and most sophisticated, hence blessed with myriad sources of rejuvenation. In July 1990, Mikhail Gorbachev conceded to the West what Stalin and successors had ferociously refused for forty years: Germany’s reunification within the West. The titanic struggle began and was played out in Germany, and so Gorbachev’s “yes” was nothing less than Moscow’s capitulation in the Cold War. To give away East Germany, the strategic brace, was to give away the entire empire.

The summer of 1990 thus opened a new chapter in the annals of “imperial overstretch.” As the Soviet Union, for forty years the bear at the door, began to limp away, the United States merely stumbled into a short recession. Yet to dwell on this snapshot is to miss the larger point, which was a revolution in international affairs.

Suddenly, the rarest moment of international history was at hand: when one international system gives way to another. The two-power world, known as “bipolarity,” vanished, and the last man standing was the United States. The strategic consequences came just as swiftly. As the Soviet Union was collapsing, the America of George H. W. Bush began to prepare for war against Saddam Hussein, and this in a region where American forces would never have dared venture while Moscow’s power was still intact. Eventually, 700,000 troops were fielded in Iraq, a quasi-ally of Moscow, and they won handily. The draft was not reinstated, nor was the economy put on a war footing. Instead, it moved into the longest expansion ever, in spite of two more wars: in Afghanistan after 9/11 and again in Iraq in 2003. Such was the “relative erosion of the United States’ position” predicted just a few years earlier.

THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: THE CHINESE ARE COMING!

Declinism mercifully took a break in the 1990s, perhaps because the United States was enjoying such a nice run after the suicide of the Soviet Union. Japan, the geoeconomic “killer app” of the 1980s, was still alive, but out of the race, where it has been ever since. Stuck in the “Lost Decade,” the superstar of the 1980s no longer stoked American angst. Though Japanese automakers continued to decimate Detroit’s Big Three, the ballyhoo about Japan had dwindled into embarrassing footnotes to history. “Gloom is the dominant mood in Japan these days,” reported an Asian commentator, while “American capitalism is resurgent, confident, and brash.”66

It doesn’t take much to vault from Declinism to triumphalism when the geopolitics is right. Hadn’t America just won the forty years’ war, aka Cold War, the longest in modern history? What other country could win a hot war, as the United States had done in Iraq in 1991, from six thousand miles away? With a high-tech, spaced-based panoply worthy of World War IV? There was no new No. 1 creeping up on the United States—nowhere on the horizon. Why even think about a military threat, as in the Soviet days? U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright crowed that America’s clout was so daunting as to render its use unnecessary. “But if we have to use force, it is because we are America; we are the indispensable nation. We stand tall, and we see further than other countries into the future. . . .”67 Depression had turned into self-aggrandizement.

After the First Iraq War, which cost only 294 American lives out of a total of 700,000 deployed, the Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer poured sarcasm on yesterday’s Declinists: “If the Roman empire had declined at [our] rate, you’d be reading this column in Latin.”68 The U.S. economy, boosted by Reaganite deregulation and Clinton’s welfare reforms, was soaring. As the budget went into surplus, unemployment virtually vanished. In Europe, by contrast, it rose above 10 percent in the late 1990s.

Decline was yesterday; now the United States had all the bragging rights. “The defining feature of world affairs” was “globalization,” exulted the New York Times’ Thomas Friedman at the 1997 World Economic Forum, “and [if] you had to design a country best suited to compete in such a world, [it would be] today’s America.” Forgotten was MITI, the all-knowing and all-powerful Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Japan was no longer the rage, though top-down modernization would soon be eulogized again as China became the new model. Now the heroes of the dot-com age bestrode the earth. They were the new masters of the universe, and they were all Americans. Those who used to go on a pilgrimage to Japan now invaded Silicon Valley. Friedman concluded on a triumphant note: “Globalization is us.”69

The occasional Declinist harrumph in those days sounded either quirky or generic like a finger exercise at the piano. Edward Luttwak, a prominent strategist in Washington, thought that the United States would turn into a “third-world country” by 2020. The path seemed straight enough—“straight downhill.” At any rate, the country was already adapting to its fate “by acquiring the necessary third-world traits of fatalistic detachment.”70 This was in 1992, on the cusp of America’s longest boom, which extended all the way to 2007.

At the end of the naughts, decline was back with a vengeance. Back was Paul Kennedy with a remake of The Rise and Fall, this time because of the global financial crisis triggered by the fall of the house of Lehman on 15 September 2008. While Russia, China, et al. might be suffering “setbacks,” the “biggest loser is understood to be Uncle Sam.” Chronic fiscal deficits and military overstretch—the twin scourges of his 1987 book—were finally doing in the United States, and the “global tectonic power shift, toward Asia and away from the West, seems hard to reverse.”71 This shift was one reason for America’s slide; the other was “American political incompetence.” There was but one consolation: great powers “take an awful long time to collapse.”72 The nice thing about prophecy is that doom never comes with a date.

“The crash of 2008 has inflicted profound damage on [America’s] standing in the world,” warned Roger Altman, formerly the deputy treasury secretary; “the crisis is an important geopolitical setback.”73 German finance minister Peer Steinbrück predicted, “The U.S. will lose its status as the superpower of the global financial system [which] will become more multipolar.”74 The Harvard historian Niall Ferguson went halfway. On the one hand, “the balance of global power is bound to shift.” On the other, “commentators should always hesitate before they prophesy the decline and fall of the United States.”75 He remained as sibylline two years later. “Empires,” he wrote, “function in apparent equilibrium for some unknowable period. And then, quite abruptly, they collapse.”76 So disaster will strike, or it may not.

Actually, most empires take a long time to collapse, like the Roman, Ottoman, or Habsburg versions, whose demise unfolded over centuries. They collapse abruptly only in war, as did the tsarist, Austrian, Wilhelmine, and Turkish empires in World War I, and Japan’s in World War II. Even in these cases, only Habsburg and the Porte literally disintegrated. Japan lost its short-lived wartime conquests, but the nation as such remained intact, turning into a commercial giant twenty-five years later. Russia just changed colors, from “White” to “Red,” and then went on to expand into the heart of Europe. It would take another great war, the Cold War, to dismantle the Soviet empire seventy-four years later.

Yet this kind of war is not in America’s future. There is no meaningful way in which others could destroy the United States, except at the price of self-immolation. In contrast to other empires, the United States will not be felled by war. Only the United States can do in the United States—as it almost did 150 years ago in the Civil War, in an attempt that is so deeply etched in the American memory that it does not invite repetition. In this century, sloth, hubris, or profligacy might gnaw at the vitality of the nation, as Declinists have prophesied for decades. But when and whether this would come to pass is indeed “unknowable,” to recall Ferguson’s key disclaimer. No such hesitation befell the Cassandras of Decline 5.0.

Some of their lore was again simply generic, that is, divorced from time and circumstance and thus achingly familiar to those who remember fifty years of similar wisdom. Two weeks after the fall of the house of Lehman in 2008, the Oxford don John Gray stressed a well-wrought theme: “The era of American global leadership . . . is over.”77 Actually, generic Declinism needs neither date nor trigger. If it isn’t repeated by the same prophet ten, twenty years down the lane, it is generational. So a few months before the Crash of 2008, the youngish Parag Khanna, of the New America Foundation in Washington, intoned, “America’s standing in the world remains in steady decline.” The disease was “imperial overstretch,” and the price was the weakening of “America’s armed forces” through overuse.78 That had a familiar ring—recall Paul Kennedy’s dirge twenty years earlier—and so did the report that “American power is in decline around the world.” These obiter dicta could have been penned in 1958, 1968, 1978. So could this one: “We are competing—and losing—in a geopolitical marketplace alongside the world’s other superpowers.”79

Who were they? It used to be Russia in the 1950s and 1970s, and Japan in the 1980s. Now it was “the European Union and China.” For Europe, it was the second time around the block. Twenty years earlier, an older generation of doomsters had touted the “rejuvenation of Europe and Japan,” hence the “relative diminishing of the enormous American superiority.”80 A fact check: During those two decades, the EU-27’s share of the global economy had dropped by 5 percentage points, and Japan’s by three, while the United States take had remained the same. In the “competitive decadence” race, gold and silver were actually going to the EU and Japan.

And yet, claimed Khanna in 2008, “America is isolated while Europe and China occupy the two ends of the great Eurasian landmass that is the perennial center of gravity of geopolitics.” Gone was not only the United States but also that colossus between Berlin and Beijing known as Russia and occupying eleven time zones. Europe was suddenly back again, perhaps because it had enjoyed a short-lived uptick in growth just prior to the Crash of 2008. One and a half years later, the Old Continent’s days in the sun were over, and so Time unveiled “The Incredible Shrinking Europe.”81 Up or down—pushing the story is punditry’s best friend.

Another recycled classic of Declinism read, “Over the past decade, the United States seemed to have lost ground in almost every conceivable area—political, economic, social, and international—and . . . its bearing in terms of values and principles. Arrogance, belligerence, individualism, and violence were trumping the values of human rights, equality, participation. . . .” As just retribution, the “United States is headed for hard times.”82 Those were the just wages of sin. Cotton Mather, Boston’s stern (and influential) Puritan minister, could not have put it more cruelly three hundred years earlier, in 1709.83

Finally, two foreign voices. One was Kishore Mahbubani’s, Singapore’s former UN ambassador, whose bid to succeed Secretary-General Kofi Annan had been thwarted by Washington. He chronicled not just the degeneration of America but the triumph of Asia, as celebrated in the subtitle of his book The New Asian Hemisphere: The Irresistible Shift of Global Power to the East. The tone was avuncular, shading off into the patronizing: “Sadly . . . , Western intellectual life continues to be dominated by those who continue to celebrate the supremacy of the West. . . .” So the “West”—read: the United States—was losing its grip not only on power but also on reality—go from Chapter 11 straight to the couch. By contrast, “the rest of the world has moved on. A steady delegitimization of Western power . . . is underway.” Now “other nations are . . . more competent in managing global . . . challenges.”84

And who would inherit the earth? Only “four real candidates [could] provide global leadership today: the United States, the European Union, China and India.” Japan, with the world’s second-largest GDP and a per capita income ten times larger than China’s, did not make it into this fellow Asian’s pantheon. The United States? As “victim of the neo-cons on the right and the neo-protectionists on the left,” it cannot bridge a “gap” between itself and the world that has “never been wider.” So America was beyond redemption, the blame falling on both Bush forty-three on the right and Barack Obama on the left, whose Democrats were bouncing around protectionist shibboleths during the 2008 campaign. Rich and populous, Europe didn’t make the cut, since it “has not been able to extend its benign influence outside its territory.” India? It is “by far the weakest of the four.” That left China, which “should eventually take over the mantle of global leadership from America.”85

This was the polite version of Atlantis Lost—wishful thinking wrapped in detached analysis. Let us complement this take with the dyspeptic, no-holds-barred version of a Russian who had seen the Soviet empire disembowel itself and, in an act of psychic revenge, projected the same fate onto the United States. The Soviet Union had succumbed to its terminal economic incompetence, and so will the United States: “At some point during the coming years . . . , the economic system of the United States will teeter and fall. . . . America’s economy will evaporate like the morning mist.”86 The author then meticulously tallied all the similarities, as he saw them, between the Soviet Union and the United States. Both were bastions of militarism, the “world’s jailers,” and deadly failures in education, ethnic integration, and health care. They were “evil empires” both.

Near the end of naughts, even before the Crash of 2008, the new Declinist consensus had settled on Asia—on China first and foremost, on India second, and on Russia and Brazil somewhere down the line. These were the fabled BRIC countries, the quartet that would inherit the world. The driver of the new dispensation was an old one. The United States was losing the growth race to those who were forging ahead at double-digit speed. In mid-decade, a former Japan booster like Clyde Prestowitz merely changed the names of the candidates in his Three Billion New Capitalists: The Great Shift of Wealth and Power to the East.87 The chapter headings tell the tale. In this new world, things would be “Made in China” and “Serviced in India.” And America was on the “Road to Ruin.”

A former editor of the Economist, Bill Emmott, saw geopolitics following economics, with power growing not from the barrel of a gun but from GDP and trade statistics. Wasn’t the World Bank predicting that China and India might triple their output in a matter of years? By the late 2020s, China would overtake the United States. And so, good-bye, America. How the Power Struggle between China, India and Japan Will Shape Our Next Decade, proclaimed the subtitle of his book Rivals.88 Japan, stuck in real decline, was in again, and the United States was out.

The Newsweek International editor Fareed Zakaria, born in India and trained at Yale and Harvard, put an original gloss on an old story in 2008. It wasn’t that America was decrepit and declining, as many previous authors had argued. America still had many assets on the ledger. Others were simply growing faster—at an awesome, unbreakable speed. A billion people in India, 1.3 billion in China—how could so much mass and momentum be stopped? Hence it was the “rise of the rest” that would dwarf the United States. And the future would belong to the “post-American world.”89 Two years later, the historian Niall Ferguson classified the United States as a “departing” power, up against the “arriving” power that was China.90 Exit Gulliver, enter the Middle Kingdom. Finally for good?

Not yet. Four years after the Crash of 2008, the Economist put a strapping Uncle Sam on its cover, cheering him as “The Comeback Kid.” Inside, the weekly announced, “Led by its inventive private sector, the economy is remaking itself. Old weaknesses are being remedied and new strengths discovered, with an agility that has much to teach to stagnant Europe and dirigiste Asia.”91 The United States was on the up; Europe and Asia were treading water. Earlier in the year, the American Interest, showing Uncle Sam punching with an oversized boxing glove, had put the same title—“The Comeback Kid”—on its cover. Inside, the journal presented articles like “How America Is Poised to Retake the Lead in the World Economy,” “The Once and Future Dollar,” and “The Population Boon.”92 Foreign Affairs put the “Demise of the Rest” on its cover. Inside, the title of the lead piece read, “Broken BRICs: Why the Rest Stopped Rising.” Highlighting the tumbling growth rates of the quartet, the author added, “None of this should be surprising because it is hard to sustain rapid growth for more than a decade.93

Usually, Declinists just come back; they never repent. One did: Roger Altman, the former deputy treasury secretary turned business consultant. A prophet of decline in 2008, he celebrated America the Beautiful four years later.94 The U.S. banking system had recovered faster “than anyone could have imagined. Capital and liquidity have been rebuilt to levels unseen in decades.” The United States had made a “huge leap in industrial competitiveness” and could look forward to bringing back jobs from the rising rest. And the “breathtaking increase in oil and gas production” would “add more than one percentage point to annual GDP growth” within five years. Declinism, it seems, is a flexible device. In this case, it took four years to transition from Jeremiah to Pollyanna.95 Through Declines 1.0 and 4.0, the American Phoenix had risen at comparable speeds.

Four years after Rivals had given the nod to China and India, its author thought that the “American century was not over.” This might be the moment to “rethink all the fashionable assumptions about America’s decline.”96 Another reformed Declinist, who had cheered Japan, China, and India in succession, now bet against them: “We are told again and again how China has enjoyed three decades of economic growth in excess of 10 percent annually, and how India and now others” were scoring in similar ways. But remember all previous economic miracles in Europe and Asia. “The truth is” that they all became unsustainable.97

In his presidential campaign of 2012, the Republican Mitt Romney sounded the trumpet for the “greatness of this country.” Whereas President Obama had deflated the notion of “American exceptionalism,” by noting that everybody else believed in his or her own country’s exceptionalism,98 Romney presented himself as “an unapologetic believer in the greatness of this country” who proclaimed, “This century must be an American century.”99 So, in fact, did the president. “America is back,” he exulted in his 2012 State of the Union address. “Anyone who tells you otherwise, who tells you that America is in decline or that our influence has waned, doesn’t know what they’re talking about.” Then he sounded a key theme of the Clinton administration: “America remains the one indispensable nation in world affairs.”100

This sanguine portrayal of the country nicely shows that Declinism is a matter of dates, just like treason, as Talleyrand quipped. The night is always darkest during a presidential campaign. In office, especially as a second-term election is looming, it is “morning again in America,” to recall Ronald Reagan’s famous TV spot. So no more “decline” for Obama, as he prepared for his second run. This not-so-exceptional country was again the “indispensable nation.”

A new cycle was unfolding, but trends, as this chapter has shown, are made up in the minds of beholders, and then for a purpose—be it political or pedagogical. Only time can tell what was a blip or a new pattern. Before we look at longer-term forces and numbers in chapter 3, let us ask why Declinism is such an evergreen. What are the functions of gloom and doom in the political discourse?