Chapter 52

Tanks

‘No thoughts of returning home alive…Writing in this diary word-by-word, not knowing when a shell may strike and I will be killed’

—Leading Private Uchiyama Seiichi, in a trench at Buna

MacArthur’s impatience reached boiling point. ‘Dear Bob,’ he wrote to Eichelberger, on 13 December:

Time is fleeting and our dangers increase with its passage. However admirable individual acts of courage may be; however important administrative functions may seem; however splendid and electrifying your presence has proven; remember that your mission is to take Buna. All other things are merely subsidiary to this. No alchemy is going to produce this for you; it can only be done in battle and sooner or later this battle must be engaged. Hasten your preparations, and when you are ready—strike, for as I have said, time is working desperately against us.

Cordially,

DOUGLAS MACARTHUR

Allied Commander.1

Japanese commanders, no less impatient, sought solace in imperial tidings. Colonel Yokoyama relayed these in a bulletin to his troops on the Papuan coast on 28 November: ‘The Emperor visited the Shinto Shrine,’ he wrote, ‘and expressed gratitude for the achievement of great victories since the outbreak of this war…He prayed for Heaven’s protection over the Imperial Army. Therefore we must perform our duties with diligence to carry out the will of His Majesty.’2

American and Japanese methods of raising morale differed, but the effect was the same: the infantry were to be driven harder, hurled at the enemy, with scarcely a thought for their condition or the wastage of life.

The carnage of frontal attacks on bunkers troubled the Australian officers; Herring responded by suggesting they ‘go quietly, take out a post here and a post there each day if possible’.3 Eichelberger’s officers, ‘torn by the suffering of their troops’, similarly argued that attempts to strike at Buna were fruitless, and that they should settle down to ‘starve out the Japanese’.4 Vasey concurred. But MacArthur and Blamey refused to countenance a relaxation of the tactics that had killed so many—‘delay is dangerous’, said Blamey—and the troops were sent back in. Tanks were on the way—tacit recognition that the unprotected assaults were ineffectual. But this did not stop Allied commanders wasting many more lives while they waited for the machines.

Nothing enraged Eichelberger so much as the Japanese bombardment of the American field hospital near Buna on 7 December 1942, on the eve of the first anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. The hospital, a series of tents marked with giant red crosses, contained three times the number of patients for whom it was designed. It became a regular target for the few remaining Zero formations. ‘There were desperately wounded men on the operating table…when the bombing began,’ wrote Eichelberger. He believed the enemy fighters ignored the front lines and supply line, ‘to concentrate on the hospital site’.5

Surgeons continued to operate; anaesthetists stayed at their posts. ‘But the tent installation was a shambles. There were 40 casualties [and] hysteria among the sick and the wounded.’6

Not all Japanese units attacked Allied medical facilities. They pointedly refrained from sinking a hospital ship at Milne Bay. Nor did the Allies show much restraint. They bombed many Japanese medical facilities which, in fairness to Allied pilots, were poorly marked.

One prisoner, Sato Tetsuro, claimed that Allied planes had strafed a clearly marked Japanese field hospital at Buna.7 One private, Onishi, 23, said the hospital at Buna was bombed at least once, with 50 patients killed. Yet the hospital’s only Red Cross insignia was a flagpole at the entrance; there were no large red crosses visible to aircraft on the tent sides. Later, at Sanananda, MacArthur dropped leaflets warning the Japanese to evacuate their field hospital before the final assault.

At last the tanks came. One night in December a large freighter drew quietly into Oro Bay, eastern Papua. In its hold were four light tanks of the 2/6th Australian Armoured Regiment—the first Allied tanks to be deployed in the Papuan war. The operation was highly complex. It had to be done in darkness. The tanks were shifted onto specially built barges, ferried ashore and hidden in the jungle. The next night the barges floated them up the coast to Boreo, near the attack point at Duropa Plantation. Four more tanks followed, in the same quiet stages.

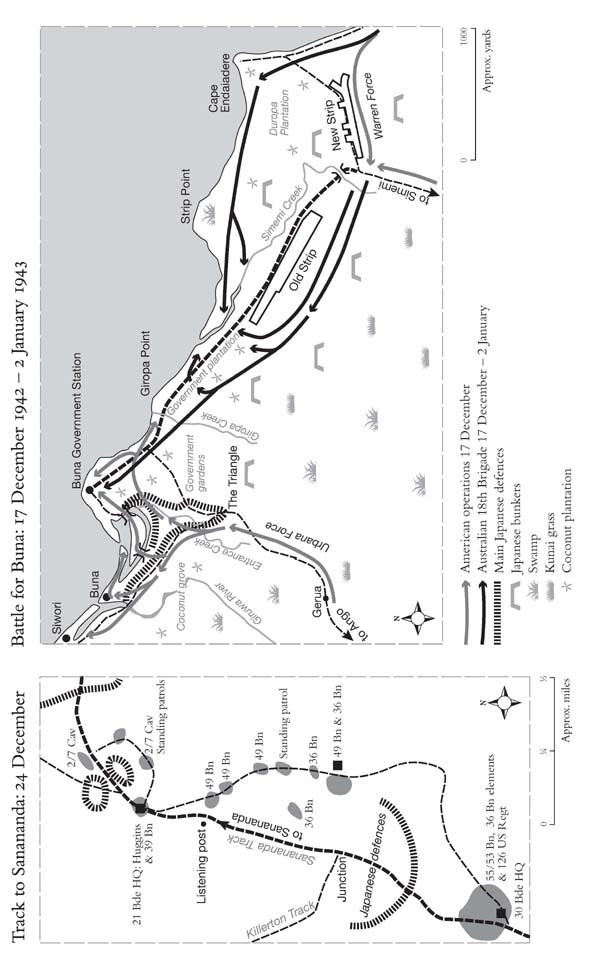

After sunset on 17 December, the tanks rumbled forward, their roaring motors and clanking tracks drowned by a deliberate barrage of mortar fire. About five hundred experienced Australian combat troops walked behind them to the assembly area.

These men formed the 18th Brigade8—veterans of Tobruk, who had inflicted the first land defeat on the Japanese, at Milne Bay. Their commander was the bull-headed, thickset Brigadier George Wootten (who would earn a KBE, DSO, CBE, CB, DSC, and be Mentioned in Despatches five times) of whom, when he toured the front lines, the joke ran that he had ‘plenty of guts’. Wootten had astonishing energy for so big a man.

‘You had to fight Wootten,’ observed Colonel Clem Cummings, one of his battalion commanders. ‘If he said something outrageous it was to see if you’d come back at him…he had a terrific bloody brain.’ Wootten used to sit through American conferences with his eyes closed: ‘You’d swear he was asleep,’ said Cummings, ‘and all of a sudden he’d bark out, “I don’t think that’s any good.”’9

That night, the officers went over Wootten’s plan in detail. Up to a thousand Japanese troops were believed entrenched in the Duropa Plantation, defending the two Buna airstrips; aerial bombardment and American raids had failed to dislodge them. The next morning an Australian force of tanks and infantry, working closely together, would find and destroy the Japanese bunkers, one by one.

It was a restless night. The soldiers smoked, had dinner, and tried to sleep. Some lay awake, reading or thinking; a few prayed. They rose at 5.30 a.m., ate a ‘scratch breakfast’10 and formed up.

At 6.50 a.m. every gun and mortar available shelled the Duropa Plantation. Ten minutes later the barrage ceased, and five tanks moved off. They were lightweight Australian Stuart tanks, and could travel up to 40 miles an hour. Not this morning: they rolled forward at the pace of the Australians crouching behind them. Huge cloth bandoleers filled with rifle ammunition were slung on their backs. ‘Like race horses harnessed to heavy ploughs,’11 the tanks clanked into the coconut groves.

The Japanese machine-guns opened up immediately. It was ‘a barbarous inferno’, said one soldier. ‘The roar of the tanks engines added to the crescendo of noise from Vickers and enemy machine-guns…The sky seemed to rain debris as small pieces of undergrowth and bark floated down like confetti…‘12

The infantry guided the tanks towards the camouflaged bunkers with flares or by hurling grenades. The tanks then rolled up to within ten or fifteen feet of the bunker, aligned their cannons, and blasted away at the crack in the earth, until the whole area was a smouldering ruin. One tank crew member said: ‘This usually took 10 rounds.’13 Then the infantry crawled forward, hurled grenades—including a new kind of phosphorus grenade that created hideous burns—into the manhole, and machine-gunned any survivors. The carnage went on for two hours; then the tanks pulled back to refuel.

The Japanese were ‘completely demoralized’.14 The tank attack had caught them utterly by surprise. Bunker after bunker was targeted, shelled and destroyed. Pockets of enemy resistance recovered and fought back: ‘Soldiers were dropping like sacks…’ wrote Bill Spencer. ‘There were no sounds from the wounded, as the pain of a gunshot wound comes later. The bodies…became sprinkled with leaf and bark litter ripped from the undergrowth by bullets and shrapnel, which somehow softened the starkness of death.’15

Many Japanese troops ran at the tanks; they’d leap on top, set fires beneath them or throw grenades at their sides. One soldier disabled a tank by jumping on it and firing several pistol rounds through the driver’s slit. ‘The man’s face was riddled with bullets and steel splinters,’ reported Herring.16 Another tank, struck by a Molotov cocktail, caught fire, but the crew survived. One master sergeant jumped on the tanks eight times in order to destroy them.17

To no avail. By nightfall, the Australians had cleared the entire Duropa Plantation of enemy bunkers, and reached the tip of Cape Endaiadere. The resistance was broken. It cost the Australian infantry 181 casualties—54 killed and 117 wounded—mostly from sniper fire in the treetops. The Japanese fared far worse: virtually the entire force was killed or wounded. Few escaped; there were no reported prisoners. Examination of the ruins revealed that some bunkers were in fact made of concrete, with steel doors. Nothing but tanks at near point-blank range could have destroyed them.

MacArthur’s latest communiqué announced a great Allied victory. In fact the action was wholly Australian—in planning and execution—but no one disabused American newspaper readers in Wisconsin, who admired their boys’ triumph in the south-west Pacific.

The few Japanese survivors retreated along the coast towards Buna Government Station, their HQ. Disbelief and denial filled their diaries during these final weeks. The unthinkable was happening—they were facing defeat for the first time. Some refused to believe it. Nothing in their training had prepared them for the emotional shock of defeat. Were they not the Emperor’s anointed army? Were they not the invincible warriors of Imperial Japan? Most calmly awaited the end, silently clinging to hopes of reinforcements and air support—and, most of all, food.

One was leading Private Uchiyama Seiichi, who sat in a trench in the Buna area in late December. He kept a detailed record of the final days, the resigned tone of which, punctured by searing bursts of emotion, was characteristic of Japanese soldiers’ notebooks:

19 November: We are continuously short of rations. Eat only once a day and impossible to walk because of lack of strength.

15 December:…Enemy plan is to annihilate us before reinforcements come…we are now completely enveloped. Bombed by enemy planes at dawn, continuously all day. We now only wait for the final moments to come.

20 December: At dawn, enemy bombed the hell out of us. Observe only the sky with bitter regrettable tears rolling down…Filled my stomach with dried bread and waited for my end to come. Oh! Remaining comrades, I shall depend on you for my revenge.

21 December: Oh! Are you going to let us die like rats in a hole? Sgt Ogawa reported that reinforcements are coming…one cannot accept such reports except as a temporary relief to one’s feelings, or as yet another false rumour. Enemy bombing fiercely and our end is coming nearer and nearer.

December 22: No thoughts of returning home alive. Want to die like a soldier and go to Yasukuni Shrine…Writing in this diary word-by-word, not knowing when a shell may strike and I will be killed. [At 5.30 p.m. that day:]…shells dropping all around the trenches. Full moon shining through the trees in the jungle, hearing the cries of the birds and insects, the breeze blowing gently and peacefully…Gathered twigs and built a fire in the trenches to avoid detection by the enemy. Good news—friendly troops are near…and friendly planes will fly tomorrow. How far is this true and how far an unfounded rumour?18

As hope faded, and rations ran out, the troops appealed to the spirits of Shinto. One soldier wrote, ‘We can only wait for aid from the gods…We may be annihilated.’19

The great westward roll of the Australian 18th Brigade, led by the tanks of the 2/6th cavalry and covered by American heavy artillery, ground to a halt at Simemi Creek. How were they to get tanks across a 125-foot log bridge, in which the retreating Yamamoto Shigeaki’s men had blown a gaping hole near the approach to the far bank? While the Australians searched for a crossing, American engineers tried to fix the hole, but enemy fire forced them back.

A shallow section of the creek, 400 yards north, was fordable. Australian rifle companies waded over and swooped on the enemy guarding the west bank, who retreated. The engineers then repaired the bridge in peace, and on Christmas Eve the four remaining tanks rumbled onto Old Strip, a mile-long airfield, disused, overgrown and lined with wreckage.

It was heavily defended. All four tanks were knocked out: two by Japanese anti-aircraft guns firing horizontally; the others got bogged down in a bomb crater and swamp.20

The troops abandoned the tank cover and ran onto Old Strip, driving the enemy back five hundred yards in the ‘bitterest kind of fighting’.21 American infantry joined the assault. This creeping battle—through swamp and over the airstrip—went on for two days, as if the armies were possessed by demented furies bent on tormenting each other a little longer.

Technology determined the end. When the American howitzer at the Simemi bridge ran out of shells, 25-pound field artillery were rolled up to the edge of New Strip. Equipped with armour-piercing projectiles at a range of 1000 yards, the gun tore through the Japanese positions at the far end of the airfield, and took out many of their remaining bunkers.

The battle for the Buna airfields was over. The eastern vicinity of Buna lay in Allied hands. The remaining Japanese, cornered in their foxholes, fought to the last man. The ‘mopping up’ was ugly in the extreme. Hand grenades tossed into Japanese bunkers were tossed back; Japanese officers came swinging their ceremonial swords through the forest in suicidal charges; snipers scurried up into the canopy—and were shot down; three fell out of a single tree. Many others roamed the jungle, fighting on for weeks.