The boyhood home of Mao Zedong is a strikingly simple farmhouse not too different from other adobe brick structures still seen nearby in the cloud-draped hills and fertile rice-producing areas of northern and central Hunan province. When the baby Mao was born in this house in December 1893, imperial China had experienced nearly a century of humiliation and was entering an especially bleak period of political disintegration. The turmoil did not subside until the adult Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Subsequent decades brought still more catastrophes to the Chinese, some of which were stimulated by the actions of Mao himself, yet he and his birthplace have remained iconic elements in the drama of China’s modern history.

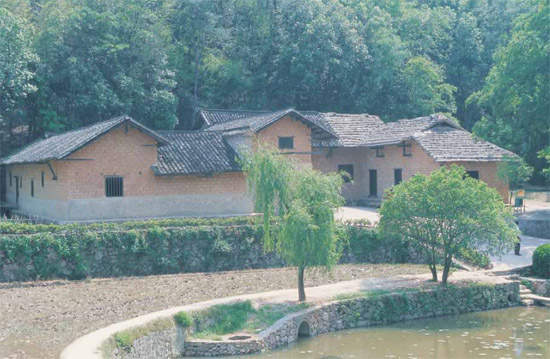

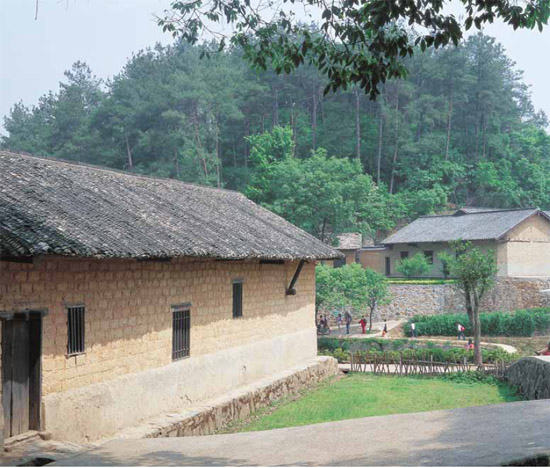

Mao Zedong’s great grandfather, Mao Enpu, purchased the house lot and adjacent farmland in Shaoshanchong around 1878, fifteen years before his grandson was born. The distinctive Hunan word chong can be translated as “hamlet,” in that it describes the small parcels of flat land suitable for building lots in the hilly area. This purchase was made principally because the extended Mao family’s homestead farther up a nearby valley was already overcrowded. The dwelling, initially consisting of merely a small rectangular, thatched five-room cottage that was used while the land was tamed and terraced, grew over time into a sprawling, inverted U-shaped structure comprised of eighteen interconnected rooms covering an area of about 556 square meters. This was the home of Mao Zedong’s youth that is still seen today. The well-ventilated dwelling is nestled on the lower portion of a steep hillside within a glade surrounded by bamboo and Masson pine trees. Its doorway and fronting courtyard face north, looking out over terraced rice paddies that cascade down towards a pond.

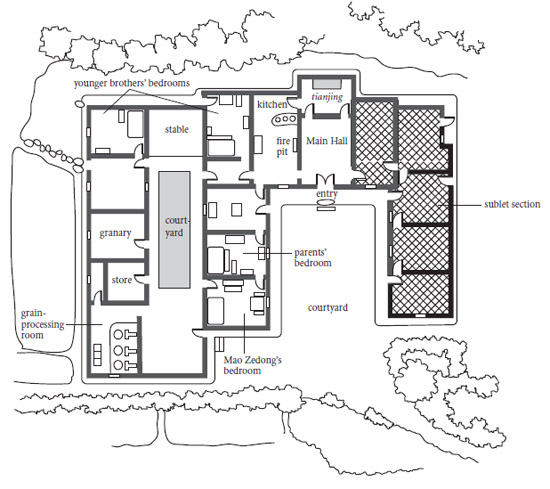

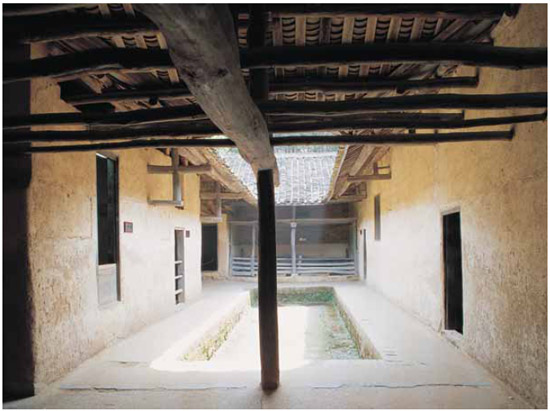

The Mao family farmhouse over time evolved into an inverted U-shaped plan with an adjacent wing that included an elongated “skywell,” called a tianjing, which is surrounded by bedrooms and working places.

The Mao farmstead is sited on a narrow patch of land at the base of a hill slope and adjacent to cascading terraced paddy fields.

In this ethereal Cultural Revolution era poster, the birthplace of Chairman Mao is shown as a pilgrimage destination for Red Guards. Some one to three million youths journeyed to Shaoshan each year between 1966 and 1976.

The expansion of the residence mirrored the rise of Mao’s father Shunsheng from a “poor” to a “middle” to a “rich” peasant—to use terms of social analysis developed later during Mao’s revolutionary life—as his small farm grew and additional income came from the buying and selling of grain. Such transformations of families and their residences were seen throughout China when fortune smiled. Typically, this involved the addition of, first, one wing, then another; the replacement of thatching with roof tiles; the setting up of an additional kitchen to service a newly married son; and the renting of surplus space to kin or neighbor. Sometimes even adobe brick walls would be replaced—one at a time—with fired bricks. Mao’s mother bore seven children in this house, two daughters and five sons, but only three boys survived. Zemin, born in 1895, and Zetan, born in 1905, like their elder brother Zedong, each had his own bedroom in the expanding dwelling. Lore has it that Mao’s immediate family only occupied the eastern thirteen rooms, which were capped with a tile roof in 1918, the year that his father reached the peak of his wealth. The western wing, with its thatched roof and five rooms, was sublet to a neighbor, also surnamed Mao. The two families jointly shared a single Main Hall. Today, the thatched roof section is not accessible to visitors.

It is said that young barefooted Mao began to labor in the nearby paddy fields when he was six, and, even after enrolling in the nearby village school, continued to help with farm work in the mornings and after school. Mao’s early schooling included the Chinese classics. However, his stern and parsimonious father was more interested in his mastering the abacus so that he could keep the increasingly complicated household accounts.

The record of Mao’s life over the next decade is replete with inconsistencies and conflicting information. It is said that in either 1907 or 1908 a marriage was arranged between the fourteen-year-old Mao and a girl of eighteen, but Mao Zedong himself did not mention such a youthful marriage. If they had been married, it is likely that the young couple would have lived together in his parents’ home, probably occupying the bedroom adjacent to theirs. The young wife, it is said, died three years later at the age of twenty-one when Mao himself was still a teenager.

Mao never wrote about traditional practices, such as nuptial customs, which most likely were observed by his family. He readily acknowledged that his mother was a devout Buddhist, unlike his father who was a non-believer. It is said that Mao fled the family farm (and perhaps his wife) in 1909 to continue his education away from the influence of his father, this time in the Tongshan Upper Primary School in Xiangtan county town. After that it was on to a school in nearby Xiangxiang, the home district of his mother’s family. Finally, he moved to Changsha, capital city of Hunan province, in 1911, to study at the First Provincial Normal School,

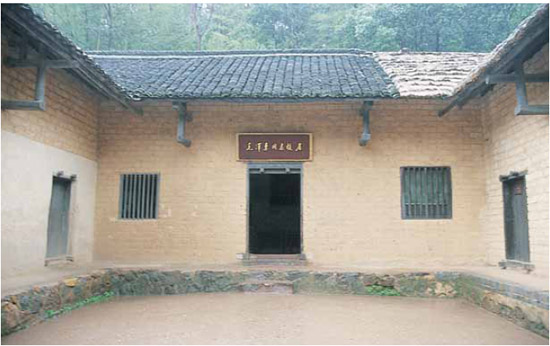

Starkly clean at present, this front courtyard, embraced by buildings on three sides, was once the principal activity center for the Mao family during daylight hours.

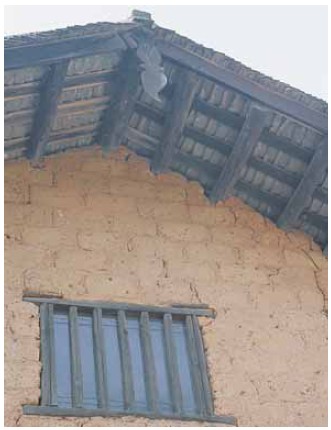

The substantial eaves overhang of the west wing helps shelter the adobe brick from being eroded by rain. The “hanging fish” is a representation of “abundance” because of a homophonous relationship between the words.

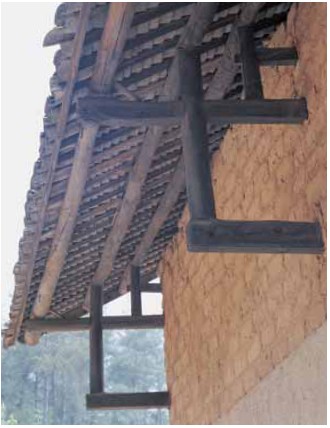

Protruding wooden bracket arms lift the purlins that support the overhanging eaves.

Looking down a slope towards the house of a neighbor, this view along the east wall of the outer wing shows the stone base, plastered lower wall, adobe brick above, as well as the tile roof.

Visiting his boyhood home in 1959, Mao Zedong walked with an old relative and other family members from his home, behind, to a nearby restaurant.

Mao’s eyes were opened to new social and political possibilities as he encountered activist notions in radical newspapers and in the thinking of teachers and students in Changsha. Mao now felt the urgency of reading “the wordless book,” the society around him, and he probably saw for the first time a map of the world. In the fall of 1918, he traveled to Beijing where he obtained a minor job in a university library working for the Marxist thinker Li Dazhao. In May 1919, he returned to Changsha, but left again, before finally returning in 1920 to teach and also to marry Yang Kaihui, usually referred to as Mao’s first wife. (She was later executed by the Nationalists in 1930.) The years away from his family and village exposed Mao to the fundamental changes taking place in China, including Sun Yatsen’s revolution in 1911, as well as to ideas flooding in from the West. By 1920 he considered himself a Marxist and on July 1, 1921 led the Hunan delegation to the fledgling First Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in Shanghai.

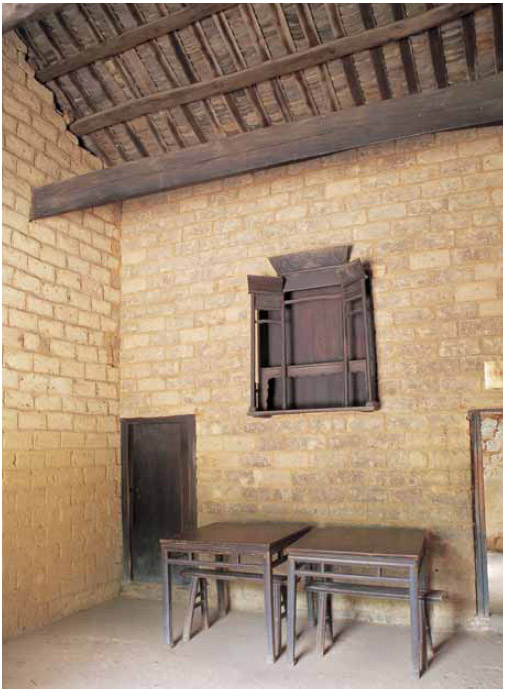

With its soaring high ceiling, the Main Hall is clearly an important room even as the open adobe brick walls and modest furniture mark its relative modesty. Stripped of ancestral tablets, the simple shenkan inserted into the back wall only hints at its centrality in times past.

Located behind the Main Hall is a transitional space that served as a pantry for the adjacent kitchen, a place to store firewood and to process vegetables. The opening in the roof lets in sunlight, ventilates smoke, and facilitates the collection of rain-water in a large vat.

Mao had returned to Shaoshan in 1919 after the death of his mother, who was simply known as “Seventh Sister of the Wen family,” but he did not come back just several months later when his father died. Subsequently, Mao only revisited his home village four times, always at critical junctures in China’s revolution. In late 1925 and 1927, he used his old home as a base to carry out a survey of peasant associations, which was the basis for his famous “Report of an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan.” This seminal document declared peasants to be China’s major revolutionary force. He also returned during the Great Leap Forward in 1959 for twenty-six days, when local peasants gave him sobering news of fabricated grain output, contrary to what others were reporting. He returned one final time in 1966 during the Cultural Revolution.

The dwelling one sees today is neatly restored and preserved. In spite of its bare walls, spartan furniture, scant farm implements, scattered photographs, and terse signs, it is not difficult to imagine what life might have been like for the farm family more than a hundred years ago. The interlinked rooms are indeed commodious, but it is important to recognize that in such Chinese farm dwellings these spaces—all under a common roof—also served as barns, granaries, and places to store brush for the kitchen stove and straw for animal fodder. They also accommodated indoor pens for animals. Throughout most of the year, the sunny front courtyard was used to dry rice and vegetables as well as to socialize with family and neighbors. Only in winter, when days are short and the sun low behind the hill, is this area in shadow throughout most of the day.

The house was elevated upon a foundation of rubble stone, requiring a stone slab step to reach it from the courtyard, even extending beyond the walls so that it is possible to move from one door to another under the cover of the overhanging eaves even when it is raining. The structure was built with relatively thick walls. The large 34 by 11.5 centimeter adobe bricks were made in molds and hardened over time in the sun. Unlike wealthier houses that have columns to support the roof, the walls here are all load-bearing. Each triangular gable directly carries the roof structure, which is made up of wooden purlins and rafters and the tiles that they support.

Viewed from the front door, the high-ceilinged Main Hall is dominated by a black lacquer shenkan, a shrine housing ancestral tablets and statues, which is set into the wall above tables containing ritual paraphernalia. Shrines were essential pieces of ritual furniture in traditional households and can still be seen in the countryside. Looking somewhat like a “building,” shrines of this type range from remarkably plain to richly detailed with carved ornamentation and mortise-and-tenon joinery. The Mao family shenkan is quite simple, lacking any refinement and reflecting essentially only practical functions (perhaps the one seen today is only a crude reconstruction). In this room is also found a square Baxian zhuo or Eight Immortals table with four trestle benches. As the center of family gatherings, tables of this type, covered with a cloth, might serve during a wedding or funeral as an offering table in front of the altar, or they could be moved to the center of the room or even into the courtyard outside where meals could be eaten or games played.

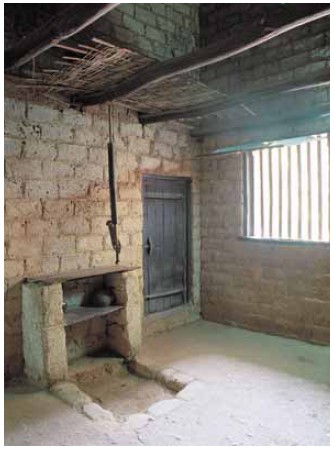

Behind the Main Hall is a transitional space under a sloping roof with an opening in the ceiling. Here rays of sunlight make food preparation for the contiguous kitchen easier. In addition to letting in light and ventilating smoke, the skywell also directs rainwater into large vats where it is stored. The area also provides space for fuel for the cooking stove: brush, grass, and charcoal collected from the hillsides. The adjacent kitchen is dominated by an imposing brick and mortar stove that sits immediately inside. Although Chinese kitchens are frequently dark and sooty, this one is commodious, with abundant work and storage space as well as places for the family to gather. There is also a fire pit. In the Hunan and Jiangxi regions, fire pits are common features in rural kitchens where, in winter, an open charcoal or coal fire could be kept burning in the recessed hearth in order to boil water in a kettle suspended from a trammel, an adjustable iron rod with a hook. The fire pit was also a place for the family to gather when it was cold. It is said that the young Zedong even assembled young members of his extended family around the warmth of the fire pit where he spoke to them of the need for peasants to participate in revolutionary activities.

When Liu Shaoqi, once China’s President, and his wife visited Mao Zedong’s birthplace in 1961, they seem to marvel at the size and utility of the old stove.

Viewed from behind and showing the three apertures used to insert fuel into the burning chamber, this large stove dominates the Mao family kitchen.

As in other areas of south-central China, homes in Hunan often have an open hearth, a charcoal or coal fire pit, that in winter provides a warm space for the family to gather. The adjustable hanging trammel can suspend a kettle of boiling water.

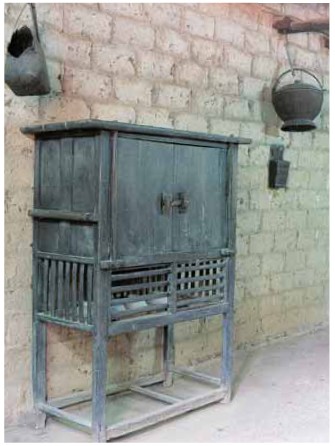

This country cupboard provided a place to store bowls, plates, and chopsticks while the baskets on the wall held herbs and spices.

There is now no evidence of a shrine to the Kitchen God, called Zaojun or Zaowang, but it is likely there once was one. Serving as tutelary deity in charge of the household rather than having any connection with the culinary arts or fire, a Kitchen God was a ubiquitous household fixture in late imperial China and relatively common even today in the countryside. Found in imperial palaces as well as in humble huts, the enshrined image had incense and candles lighted before it daily in addition to periodic food offerings. Prior to the lunar New Year, the paper image of Zaojun, blackened with soot from a year in the kitchen, is burned. As the smoke rises, he ascends to Heaven to report to the Jade Emperor on the family members’ behavior since his previous journey.

Just beyond the kitchen, past a small room with a square table and benches, is Mao’s parents’ bedroom. It contains the bed where his 26-year-old mother gave birth to him and his siblings. Adjacent to this is the bedroom of Mao Zedong’s youth. Like all of the bedrooms, this small room is dominated by a bulky wooden canopy bed, called babu chuang, a veritable room within a room. Gauze curtains offered little seclusion but some respite from mosquitoes. Marital beds of this type were sometimes brought as part of a new bride’s dowry, but it is not clear where this particular bed came from. On the wall nearby is a tong oil lamp made of bamboo. The young Mao, who was known as a voracious reader, is said to have used it to read late at night. The flame resembles a bean in shape and size, casting just enough light to read but not enough to arouse the suspicion of his strict father. He sometimes retreated for more privacy, through a trap door in the ceiling of his room, to the airy loft above, which has a window. In this bedroom, Mao is said to have gathered family and other villagers in 1925 and 1927 to talk about the peasant movement. When Mao returned home during the Great Leap Forward, thirty-two years after an earlier visit, he spotted on the wall across from the bed a photograph of his mother, himself, and his two brothers, taken in 1919. He asked where the photograph came from, declaring that it was probably the earliest picture of him, taken when he was about twenty-six. He often stated that he resembled his mother.

Just beyond Mao’s bedroom is a very large rectangular courtyard surrounded by storage rooms for farm implements and produce, livestock sheds, and the bedrooms of his two younger brothers. Bathed in sunlight for parts of every day, this courtyard, with its recessed core and shaded margins, provided a work space for husking and cleaning harvested rice. In the southwest corner room sits a hand rice mill for separating the hulls. Nearby are several foot-balanced pestles and mortars used to polish rice in order to remove the glumes. Adjacent is a large room that served as the granary where a large amount of unhusked rice was stored. The bedrooms of Zedong’s two brothers lie adjacent to the pigpen and stable for cattle. Rear and side exits open to a broad terrace used to dry harvested rice in preparation for its storage inside the house.

The young boy, of course, became the Great Helmsman, and the hamlet of Shaoshan and his boyhood residence played their roles in his fluctuating fortunes. After a youth spent working around the house, the young Mao left the village for education. Introduction into social movements led rather quickly to his role in the formation of the Chinese Communist Party. When he returned in the later 1920s, he appears to have gained inspiration from the struggles of peasants, with whom he was familiar.

In 1929, the Nationalist government confiscated the house and its furnishings. Substantial deterioration and destruction had occurred by the time the house and land were returned to Mao’s brother’s family in 1937. After 1949, the building itself was restored and some furniture returned. In 1953, the site was put under national protection and opened to visitors. During the high tide of the Great Proletarian Culture in the decade after 1966, Shaoshan became a kind of pilgrimage destination for between one and three million people a year, especially Red Guards drawn by the mystique and the veritable cult of Mao Zedong. When Mao himself retreated to Shaoshan for ten days in June 1966 to meditate on the course of the Cultural Revolution, he stayed in a newly constructed villa near Dripping Water Cave not far from his grandfather’s original farmhouse. He spoke of retiring to this bucolic village with the hope of living in a simple thatched-roof cottage.

Mao Zedong’s small bedroom is dominated by a bulky canopy bed, a veritable room within a room. On the nearby wall is a tong oil lamp made of bamboo (left, shown enlarged), which cast just enough light for the young Mao Zedong to read. The small flame resembles a bean in shape and size.

Adjacent to the elongated skywell, a room holds equipment to process farm products, including a number of foot-balanced pestles and mortars used to polish rice.

In addition to farm implements such as the winnower shown in the rear, the room also holds a hand rice mill for separating the hulls.

This elongated skywell has around it not only storage rooms, a granary, pens for pigs and cattle, but also the bedrooms of Mao Zedong’s two younger brothers.

After Mao’s death on September 9, 1976 until the hundredth anniversary of his birth in 1993, the number of visitors to Shaoshan dropped precipitously. When the peripatetic travel writer Paul Theroux came in the 1980s, he discovered that “the tide was out in Shaoshan; it was a town that time forgot— ghostly and echoing.” Since then, however, especially as domestic tourism has become a growth industry, local pride and civic boosterism relating to Shaoshan’s native son have led to the revitalization and commercialization of the village. Important historical sites, such as Mao’s residence, Mao’s school, and the Mao clan Ancestral Hall have been fitted into a tapestry of visitor experiences that now include a multitude of Mao family restaurants, an extensive Mao museum, a Mao library, a Mao research center, and landscaped public gardens. In addition, a comprehensive Mao Zedong theme park operates nearby, where visitors can in a single day savor each of the significant places throughout the country associated with the life and legend of the Chairman. Mao Zedong—revolutionary hero and common man— has become a cottage industry in his transformed village, a socialist icon commodified by capitalist entrepreneurs. The immediate environs around Mao’s birthplace nonetheless remain relatively unchanged, providing a quaintly ageless glimpse of a late nineteenth-century farmstead. In a country that today is undergoing a truly “revolutionary” transformation, one can find quiet whispers of the circumstances that propelled the young Mao on his extraordinary path.

Poem written by Mao Zedong to commemorate his visit to Shaoshan in 1959:

Shaoshan Revisited, June 1959

Like a dim dream recalled, I curse the long-fled past...

My native soil two and thirty years gone by.

The red flag roused the serf, halberd in hand,

While the despot’s black talons held his whip aloft.

Bitter sacrifice strengthens bold resolve

Which dares to make sun and moon shine in new skies.

Happy, I see wave upon wave of paddy and beans,

And all around heroes home-bound in the evening mist.

Mao Tsetung Poems, Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1976

Quotations from Mao Zedong:

“A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.”

Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan (1927)

“A man in China is usually subjected to the domination of three systems of authority [political authority, clan authority, and religious authority].... As for women, in addition to being dominated by these three systems of authority, they are also dominated by the men [the authority of the husband]. These four authorities—political, clan, religious and masculine—are the embodiment of the whole feudal-patriarchal ideology and system, and are the four thick ropes binding the Chinese people, particularly the peasants.”

Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan (1927)

“All men must die, but death can vary in its significance. The ancient Chinese writer Sima Qian said, ‘Though death befalls all men alike, it may be weightier than Mount Tai or lighter than a feather.’ To die for the people is weightier than Mount Tai, but to work for the fascists and die for the exploiters and oppressors is lighter than a feather.”

Serve the People (1944)

“You can’t solve a problem? Well, get down and investigate the present facts and its past history! When you have investigated the problem thoroughly, you will know how to solve it. Conclusions invariably come after investigation, and not before. Only a blockhead cudgels his brains on his own, or together with a group, to ‘find a solution’ or ‘evolve an idea’ without making any investigation. It must be stressed that this cannot possibly lead to any effective solution or any good idea.”

Oppose Book Worship (1930)

“Letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend is the policy for promoting the progress of the arts and the sciences and a flourishing socialist culture in our land. Different forms and styles in art should develop freely and different schools in science should contend freely.”

On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People (1957)

Regarded as the first photograph of Mao Zedong (right), this image taken in 1919 when he was twenty-six includes his mother, himself, and his two brothers. Mao sometimes declared that he resembled his mother.