When Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic of China atop the rostrum facing Tiananmen Square on October 1, 1949, a fellow Hunan native named Liu Shaoqi was at his side. Liu was a pragmatic theorist and seasoned administrator whose abilities led many to see him as the steward of Mao’s revolutionary legacy and Mao’s presumptive successor. Tragically, Liu’s fortunes instead abruptly turned as his promotion of practical economic policies eventually came into conflict with Mao’s more ideological urges. Despite having served as China’s Head of State from 1959 to 1967, Liu Shaoqi was labeled the “number one capitalist-roader” and “renegade, traitor, and scab” during the early stages of the Cultural Revolution. Although thrown onto the “ash heap of history” and banished to oblivion, Liu has since undergone a political resurrection that also provides a peek into his formative years.

Liu Shaoqi (originally called Liu Shaoxuan) was born in Tanzichong hamlet of Huaminglou township in Ningxiang county, just 30 kilometers across a mountain range from Mao’s birthplace in Shaoshan. Unlike Mao, Liu was born into comfortable family circumstances and in his early years enjoyed a significantly more cosmopolitan life. In 1948, he married, some say for the fourth time, a new wife named Wang Guangmei, a university graduate some twenty-four years younger than he. During the nearly twenty years that he served as a high official, together they paid state visits to many countries. In Beijing, they lived in Zhongnanhai, the walled sanctuary for China’s Communist rulers, but the imposing walls did not ultimately provide safe haven for either of them. In January 1967, Red Guards were able to break into their residence and post “big character posters” on the walls. They dragged them out for public criticism and humiliation in their own courtyard. Liu, it is said, offered to resign, telling Chairman Mao that he would like to return to live and work either in his home village in Hunan or in the revolutionary caves of Yanan. However, in 1968 Liu Shaoqi was stripped of power and disgraced. He became bedridden with untreated pneumonia, and died a lonely death on the floor of an unheated building in Henan province in 1969, midway between his boyhood country home in Hunan and Beijing. His death was not made public until 1974, while his wife, who had accompanied him to his boyhood home in 1961, suffered confinement for ten years until her release in 1977.

This oblique view of the long façade of the boyhood home of Liu Shaoqi reveals that the surface of the adobe walls has been parged with a thin coat of viscous mud. It is likely that there were no windows in the early house and that those now seen were opened later.

Built around 1870, the Liu house was sited so that it is wrapped from behind by a copse of trees on a hilly slope and faces a large pond.

Oriented so that it faces west, this expansive farm dwelling, shown here in plan view, includes two large courtyards and several smaller skywells.

Little is known of the history of the Liu family dwelling except that it was built in 1871 by Shaoqi’s grandfather when Shaoqi’s father was six years old, twenty-seven years before China’s future “President” was born there on November 24, 1898. Once the grandfather died in 1875, the two surviving sons raised their own families in the large house. At some point the building was divided and a line drawn down the center of the Main Hall to indicate a sharing of ritual space. This created two attached, yet separate, residences joined across a courtyard.

Both brothers came to be considered rich landowners and supported large families. Liu Shousheng, Liu Shaoqi’s father, died in 1910 when his son was not yet a teenager. His mother managed the large family of four sons and two daughters, living with her sons until she died in 1931. Liu Shousheng’s elder brother struggled to hold onto his half of the estate but went bankrupt in 1930. He sold his interest to a neighbor surnamed Xia. Thus, a significant portion of a residence built by the prosperous grandfather— with the hope that it would house many offspring of the Liu family—had in just two generations been divided, with partial ownership passing to a non-family member, a common practice in difficult times.

The rehabilitation of Liu Shaoqi from political oblivion is suggested by the fact that the characters above the door that declare “The Former Home of Comrade Liu Shaoqi” were written by Deng Xiaoping.

Barren of activity and ornamentation once characteristic of such a central room, the Main Hall is today dominated by a large empty wooden cabinet which once contained a shenkan, the family’s ancestral tablet shrine.

Liu Shaoqi’s bedroom contains a bulky wooden alcove bed, an enclosed space within an enclosed space, fitted with curtains made of a loose open-weave thin gauze fabric and with padded cotton bedding. Near it is a writing desk with an oversize armchair. The picture on the wall portrays Liu using the desk during the week in 1961 when he stayed in his boyhood room. Rare in bedrooms is an interior window that opens to an adjacent skywell, allowing light and air to enter.

Shaoqi, meanwhile, continued to live in the house with his mother and brothers, until he left in 1919 to attend middle school in Changsha, the provincial capital. He later journeyed beyond Hunan to Beijing to study either French or German, and then to Shanghai to study Russian. In 1920, he joined a socialist youth group and had the opportunity to live and study in Moscow for less than a year. It was at Moscow’s Communist University of the Toilers of the East (KUTV), a special institution for budding Communists from Asia, that Liu Shaoqi came to appreciate Leninist ideology. And it was here that he joined the newly formed Chinese Communist Party. After he returned to China, he became Mao’s confidant, rising rapidly, becoming first a member of the Central Committee in 1927 and then of the powerful Politburo in 1934. Often working in the under-ground, he honed his skills as a labor and party organizer. Even though he differed from Mao in temperament and in his approach to revolutionary change, by 1942 he was championing the study of “Mao Zedong thought” as a contribution to Marxism, whose form already had gone beyond the rudimentary stage.

Through the end of the 1950s, Liu Shaoqi remained the steady bureaucrat supporting the ideologue Mao. The euphoria of nation building, however, was soon dampened by the apocalyptic failures of Mao’s Great Leap Forward and the creation of Peoples Communes. Beginning in 1958, this movement led to famine and the deaths of at least twenty million people over a three-year period. Mao contemplated “retiring” from political life and the country turned to the pragmatic Liu Shaoqi to lead the economic recovery. To many in China, intractable problems began to increasingly emerge.

Baskets are hung on a kitchen wall near the stove in order to store herbs and spices.

Volumetric measures used to determine an amount of grain.

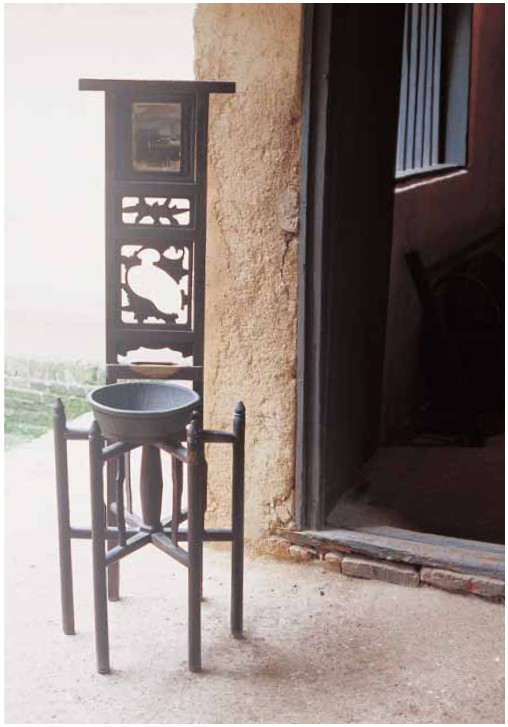

In the kitchen or in the bedroom, an ornamented wash-stand serves to hold a metal washbasin and as a place to drape a washcloth to dry.

It was at this juncture, in May 1961, that Liu Shaoqi, together with his wife, returned to his boyhood home, which he had last seen in 1919, in an effort to personally understand the failure of the commune system. Traveling for a month in Hunan, including time in Mao’s home village in Shaoshan, he spent six nights in his old bedroom in the family homestead in Ningxiang. Even though the Liu residence had been designated an historic site and converted into a little-visited museum in 1958, Liu Shaoqi requested that this designation be rescinded and that local peasants be permitted to live in the old dwelling. After he became a pariah and scapegoat during the Cultural Revolution, his ancestral residence was ransacked and its contents scattered or destroyed. A neighbor took down the sign declaring the site “The Former Residence of Comrade Liu Shaoqi” and feigned destroying it by turning it upside down and using it as a tabletop. After being cleaned up, this original sign now hangs above the entrance to the Main Hall. Above the main entry is a similar sign, but this one in the calligraphy of Deng Xiaoping a powerful affirmation of Liu’s rehabilitation.

While Liu Shaoqi’s birthplace appears similar to that of Mao Zedong’s, closer inspection reveals a definite class difference between the two. The expansive Liu residence is clearly that of a successful and rich landowner while that of the Mao family bespeaks the struggle of a small peasant to make the transition from scarcity to self-sufficiency. Located in a hamlet called Tanzichong, the Liu homestead is situated among undulating low hills also known for the production of tea and rice. Like other well-sited farmhouses, it is wrapped from behind with a copse of trees and faces a large pond. Both features far exceed the scale of those of the Mao family homestead. The house faces west, a rather uncommon direction, but the overall setting was obviously carefully chosen. The middle third of the front wall, which includes the main entry portico, was not built parallel or perpendicular to other walls of the house. A deviation of this sort can only be explained as a fengshui master’s attempt to assure the good fortunes of the family. As with the Mao house, the Liu dwelling was built using adobe bricks. However, all the walls, inside and out, were parged with a thick coat of ochre mud plaster that required regular maintenance. This represents a qualitative improvement over common adobe brick.

When viewed from the outside, it is relatively easy to divide the residence into two parts. The right or southern half is the portion inherited by Liu Shaoqi’s father, while the rest belonged to his father’s elder brother who sold it. A large courtyard, entered via a substantial portico, leads directly to the Main Hall, which is dominated by a large wooden cabinet with a shenkan, or ancestral tablet shrine above it. The room today is barren of any of the life and ritual that must once have animated its spaces. From the Main Hall, a door leads to the bedroom of the second eldest son with another door leading into Liu Shaoqi’s own bedroom.

Liu Shaoqi’s bedroom is nicely situated in that it has not only three doors but also a window that opens to an adjacent tianjing, allowing light and air to enter. Like Mao’s bed, Liu’s is a hulking wooden alcove or canopy bed, an enclosed space within an enclosed space, fitted with curtains made of a loose open-weave thin gauze fabric and with padded cotton bedding. Adjacent to the bed is a substantial writing desk with an oversize armchair. The picture on the wall portrays Liu using the desk during the week in 1961 when he stayed in his boyhood room.

Outside his bedroom, around the tianjing, is a room for making and storing wine, a bedroom for his elder brother, his parents’ bedroom, a spacious utility room, which has a second tianjing alongside it, and another brother’s bedroom. Behind these are several “studies,” some of which may have been used by tutors engaged to help educate the sons.

Completing the circuit of rooms in the southwest quadrant of the house is a very large barn-like area for unhusked grain, with adjacent milling and polishing equipment. The rice container is nearly two meters high and capable of holding a year’s worth of grain. Next to this are a large pigsty, a cattle pen, and a storage room for farm implements, fuel, and foodstuffs. Adjacent to this space is a rectangular tianjing open to the sky, which brings abundant light, air, and water into this functionally important part of the house.

On the opposite side of the tianjing, separated from the main courtyard by a wall, is the kitchen, the largest room in the dwelling. The brick and mortar stove is situated just inside a window overlooking the courtyard. The three circular openings can hold various round concave pans, which with their flared sides and depth concentrate heat at the bottom and minimize the use of oil. Commonly called in English “woks,” from the Cantonese pronunciation of the generic Chinese word for cauldron, bowl-shaped pans of this type are multi-use vessels that allow a cook to stir-fry, steam, braise, sauté, simmer, deep fat-fry, stew and even smoke without the need for other types of pots or pans. Stoves of this sort usually require two individuals to operate them. One cooks in front while the other squats feeding fuel into the rear of the stove. The two must work together to maintain the proper temperatures. Since there is no chimney, a rush mat is tilted between the top of the stove and the ceiling in order to direct some of the smoke towards the window and keep it from the cook’s face or the food. Nearby is a pantry where jars of salted and pickled vegetables were kept and where dried herbs hung in baskets. Unlike the Mao family kitchen, which includes a fire pit, here the fire pit is in a smaller adjacent room, where the heat can be better concentrated and not dissipated by the greater space of the open kitchen, tianjing, storage areas, and animal pens of the Liu house.

Liu Shaoqi was posthumously rehabilitated in 1980, four years after Mao’s death, reclaiming his place in the Communist pantheon as a “first generation leader.” In January 1988, his former residence was designated a national historic site with substantial expenditures allocated to renovate it. Over the past decade and a half, moreover, hundreds of acres of surrounding farmland have been transformed into a park-like precinct celebrating the life of Liu Shaoqi. In addition to long paths and abundant gardens, an imposing statue square, memorial hall, comprehensive museum, and even his airplane, have joined his former residence as elements representing a long life in service to China. Today, Liu Shaoqi’s 1939 pamphlet How to be a Good Communist is hailed as a classic that synthesizes Communist ethics with Confucian virtues, and he himself is declared to be a revolutionary with “boundless rectitude, awe-inspiring righteousness.”

Between the kitchen and a dry storage area for fuel and grain is a recessed skywell, which provides a lighted area to work as well as a place for rainwater to be collected and stored. On the far right is a hulking storage container for unhusked rice, with sufficient volume to meet family needs over the winter months.

Quotations from Liu Shaoqi:

“There is no such thing as a perfect leader either in the past or present, in China or elsewhere. If there is one, he is only pretending—like a pig inserting scallions into its nose in an effort to look like an elephant.”

On self-cultivation: “We should not look upon ourselves as immutable, perfect and sacrosanct, as persons who need not and cannot be changed.”

Whatever the size of the kitchen, a large brick stove usually dominates. In this nineteenth-century print, one woman enters as another sits to eat. Woven baskets are hung on the wall and brush for fuel is stored behind the stove. The Kitchen God’s altar, with incense placed before it, sits atop the stove.

Adjacent to a window for ventilation, this stove also employs a screen to block the cook from being buffeted by smoke rising from the fire holes in the rear. Two persons must operate a stove, one controlling fuel in the rear and the other cooking in front.

Close-up of the fire holes at the rear of the stove. Using metal tongs, fuel is inserted deep into the belly of the stove in order to maintain a constant temperature.

In an alcove just beyond the kitchen is a table with benches for eating and working.

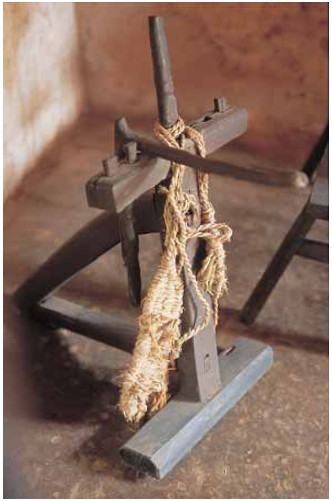

Using a bench and a frame laced with twisted strings of straw, a worker could make some of the household’s own utilitarian footgear. After “weaving” a sandal, it is necessary to beat it with a mallet on the stone floor in order to soften the straw before it can be worn.

This large storage area adjacent to the kitchen also has a doorway to the outside. Here farm implements are stored and agricultural products stacked before being processed and used.