Located in northeastern Sichuan province, Langzhong is heralded as one of the province’s oldest and best-sited towns. Viewed from atop the undulating Mount Jinping (“Brocaded Screen Mountain”), which sits across the Jialing River to the south of Langzhong, the town appears to have been cupped by the curvature of the river. In fact, the overall site of Langzhong with its encircling mountains to the rear, a river sweeping along its sides and passing to its front, together with Mount Jinping, provides what many consider to be one of the most complete fengshui landscape configurations in China. The city is strictly orientated according to the cardinal directions, with its principal buildings facing south towards the river and hills beyond. Although the city has a history that reaches to the Qin dynasty in the third century BCE, it was not until the Tang dynasty in the seventh century that the current city site was chosen and a rectangular wall built to secure it. The city wall with its four gates is long gone, yet the location of the lanes and style of shops is said to evoke patterns of the Tang dynasty. What largely remains is the area that had developed outside the East Gate of the walled city, which is said to have had ninety-two streets and lanes, a compact town of approximately 1.5 square kilometers.

When viewed from atop 36-meter-tall Huaguang Tower, with its sweeping upturned roofline, the low rooftops of Langzhong in this area outside the old walls appear as an expanse of gray-tiled single-storied structures punctuated by courtyards and skywells of different sizes, which are aligned along a grid of streets and lanes. Commercial areas with shops and workshops are separate from the better residential areas, but shopkeepers live in spaces built adjacent to their workplaces. More than a thousand old structures, including residences, shops, guildhalls, temples, and an examination hall, line the lanes, with most having a projecting eaves overhang to shield the wooden fronts from heavy rain and provide some relief for pedestrians during downpours. During summer, bamboo poles are used to support canvas canopies to shade the lanes, and merchants bring their goods out onto the street.

This 1871 map of Langzhong, looking north, is said to exemplify one of the best fengshui sites of any Chinese city. The wall surrounding the settlement is said to date to the seventh century during the Tang dynasty, but what is depicted, including prominent buildings, is a view during the nineteenth century.

Viewed from above, the low rooftops of Langzhong appear as an expanse of gray-tiled single-storied structures that are punctuated by courtyards and sky-wells of different sizes.

Paved with stone slabs, the streets and lanes of old Langzhong form a relatively consistent grid.

Most of the old houses in Langzhong are still occupied by their owners, and visitors only come in relatively small numbers. It is easy to taste the atmosphere of times past since there are relatively few modern intrusions into the old town. Lanes are too narrow for buses or cars, so pedestrians, pedicabs, and bicycles dominate. Utility poles for electricity and a simple sewage system have made life somewhat more convenient for residents. As in many Sichuan towns and villages, teahouses and periodic fairs were traditionally intimate parts of the cultural landscape. Itinerant peddlers and craftsmen still ply the lanes in Langzhong, where they sharpen knives and scissors, collect paper, bottles, and cans, sell fruits and vegetables, give haircuts, essentially supplying most of the needs of women, especially, who spend most of their time behind the gates of their houses. One indispensable commodity in Langzhong is Baoning vinegar, which can be purchased in some twenty varieties from shops throughout the city. Full glasses of Baoning vinegar are consumed as a beverage by residents each day, since vinegar brewed from wheat bran is said to cure ailments, especially those relating to internal organs. Meals in Langzhong are usually served with two glasses, one for wine and one for the dark vinegar, sometimes called “Langzhong tea.”

Several old residences are still relatively intact, with little evidence of the senseless ravages of past political campaigns or the abuse by large numbers of people living in them in modern times. Even some of the dayuan or “big courtyards” of old families are cared for by aged family members. Tourism has led to the conversion of some old houses into inns, but, for the most part, Langzhong has yet to attract the attention of visitors. Among the better preserved old dwellings are those of the Du family, Zhang family, Hu family, Sun family, Hua family, and Kong family, but only the Ma and Feng family residences are discussed below. Little written information is available about any of these families.

What is today called the Ma family residence is said to have been built by a migrant from the southeast coastal province of Guangdong, who came to the region in the middle of the 1600s, a time of dynastic change when people moved long distances to better their fortunes. At some point, the dwelling was sold to the Ma family, which has occupied it at least since 1895. The rectangular plan includes three parallel structures, two with double-sloped roofs and the third only with a single-sloped roof. The first structure abutting the street is four bays wide, a configuration that is relatively uncommon since most people view four as asymmetrical and unlucky in that the number four is homophonous with the word “death.” One of the four bays serves as a broad and deep entry portico, with six adjacent small rooms, which then opens into an outer courtyard leading directly to the large open Main Hall. The side rooms as well as those adjacent to the rear courtyard served as bedrooms. Today, all the rooms stand vacant, clearly tidied up but not yet brought to life with furniture and ornamentation. The flanking side rooms are decorated with beautiful lattice door and window panels as well as structural supports. Unlike the lattice windows in common dwellings, these were sealed with semi-transparent thin leaves of mica, a crystalline mineral found in abundance in the province. In addition to the two courtyards, there are three tianjing that open up the interior spaces. A kitchen and toilet are located in the rear of the house. Adjacent to the rear courtyard are stairs that lead to a second-story structure, said to be a room used by the family for leisure purposes. In Sichuan, elevated rooms of this sort are called “rooms for gazing at the moon,” with their importance underscored by being placed directly on the axis passing through the Main Hall. From the upstairs room in the Ma residence it is possible to see Jinping Hill in the distance. The amount of structural and ornamental wood seen throughout the house clearly indicates that someone with wealth built the house, although virtually nothing is known of the circumstances of construction. Like farmhouses throughout Sichuan, the depth of each structure is substantial, made possible by employing a pillar-and-transverse tie beam wooden framework in which the outer portions act as buttresses to stabilize the building. The Main Hall structure at the center is broader, deeper, and higher than either of the other buildings, underscoring its centrality and importance.

Looking south towards the curved Jialing River, which embraces the town and its agricultural hinterland, this drawing reveals the multiplicity of named sites of Mount Jinping that constitute the rich inherited cultural landscape of Langzhong. Huaguang Tower is shown here as being outside the walled city.

As it did in centuries past, the 36-meter-tall Huaguang Tower, with its sweeping upturned roofline, dominates the old section of Langzhong.

“Olde Town” Langzhong today preserves many of the traditional shops, with their removable wooden panel fronts, that once lined its lanes and streets.

The Feng residence is similar but larger than the Ma residence, covering an area of about 1000 square meters with some thirty rooms. Like the Ma residence, the house was built by one family, in this case named Wang, who sold it in the late nineteenth century to an in-migrant from Gansu province named Feng. In 1935, the complex was taken over as the local headquarters for the Red Army until after 1949 when it became the office for the Baoning township government. It is likely that occupation by government officials saved the structure from the collateral damage associated especially with the Cultural Revolution. The Feng residence was opened to the public in mid-2003.

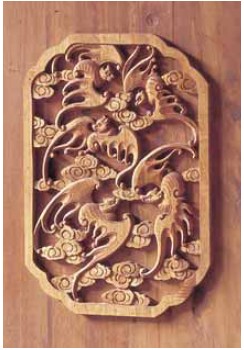

Entered directly from the street, the entry portico leads to a rectangular courtyard with flanking side buildings. As with other structures with tall lattice doors, the door panels can be removed in order to open and connect interior and exterior spaces. One must cross a threshold to enter the high Main Hall or tangwu, where a suite of hardwood furniture, comprising tables and chairs of various types, are placed in standard symmetrical positions relative to each other. Lattice and door panel carvings here are especially exquisite and well-preserved. Decorative motifs, whether on furniture, on door or window panels, or high under the eaves on brackets, are rarely without an auspicious meaning. Ornamented with both geometrical and didactic forms, the upper portions of doors and windows usually include perforated lattice in order to maximize ventilation, while the lower solid panels are frequently carved in bas relief patterns.

View into the narrow courtyard of the Ma family residence showing the sloping rooflines that draw water into the house.

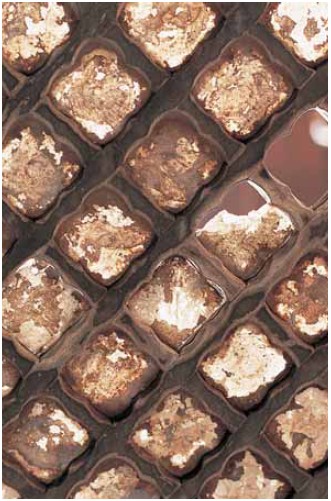

Shown from a distance and in close-up, the well-carved lattice doors and windows of the Ma home were sealed with semi-transparent thin leaves of mica, a crystalline mineral found in abundance in the province, rather than with the thin rice paper used in many other parts of the country.

Four of the wooden panels along the façade of this side hall are removable or may be opened on a pivot while four others are stationary.

The inner or second courtyard also is stone-lined, with deep overhanging roofs protecting the wooden panels from rain-wash. Here, under the branches of several tall trees, children and women, especially, had privacy in their daily lives. The two-courtyard pattern found in most of these dwellings is said to resemble the Chinese character duo, meaning “many,” thus is said to serve as an auspicious symbol invoking the hope for “many children.”

Interest in preserving and rehabilitating the oldest parts of Langzhong began in earnest in the late 1980s. With indiscreet modern buildings increasingly overlooking the old town and impinging on its authenticity, local boosters began to call for the development of a conservation policy in order to forestall change and to begin plans for revitalizing the historic town through tourism.

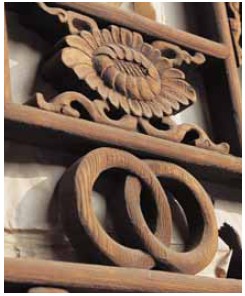

Detail of a carved lattice panel with running chrysanthemums, a symbol of long life. Under it is a pair of inter-locking circles, which serve as decorative struts between the stretchers.

Carved ornamented bracket in a pattern of spiraling vines used to support a beam.

This attenuated section view of the Ma residence portrays the two courtyards and the three transverse structures that dominate its spatial organization. It also illustrates the pillars-and-transverse tie beams wooden framework employed throughout the residence.

This floor plan reveals that the Ma residence has an odd four-bay structure, two large courtyards, several small sky-wells, and a second story in the rear, the latter described as a “room for gazing at the moon.” Indeed, it is possible to see Jinping Hill in the distance and, periodically, the moon when it is in the southern sky.

This elevation drawing portrays the asymmetrical façade as well as the textures of brick, tile, and wood.

More recently, voices have been raised calling for the preparation of documents to elevate Langzhong to UNESCO World Heritage Status. A decade ago, some 30,000 of Langzhong’s total population of 860,000 lived along the old lanes. About 10,000 have already been resettled elsewhere in order to upgrade their living conditions and lessen wear and tear on the old structures. Intrusive utilities like telephone and electric poles have, for the most part, been placed underground, and drainage has been improved. Newer structures that had been built over the years amidst the old ones have been torn down, with their building lots infilled with new structures that match. In Langzhong, as in some other areas of the country, there is also concern for the preservation of local folk arts and crafts, which like buildings themselves, are under threat.

Yet to be filled with furniture and wall hangings, this corner of the open Main Hall in the Ma residence reveals its exceptional breadth and height, which were made possible by the use of a pillars-and-transverse tie beams wooden framework, also called the chuandou framing system.

Shaded courtyard of the Feng family residence viewed from a covered structure that is usable even during periods of heavy rain.

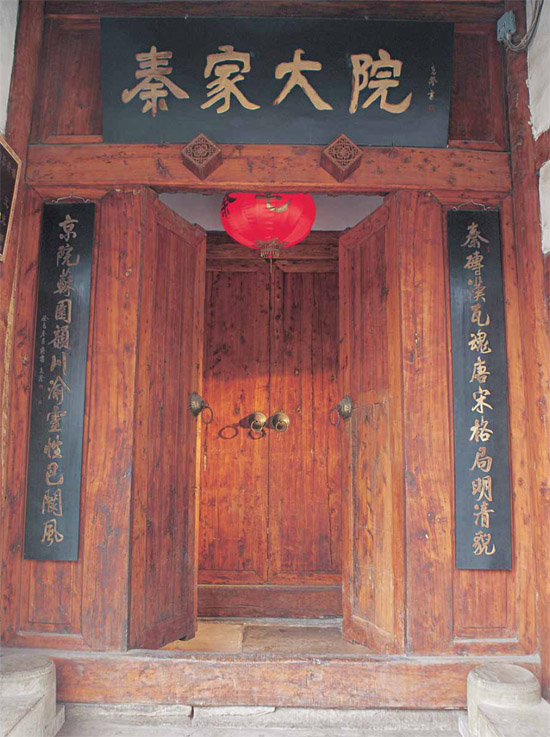

Opened to the public in 2003, the expansive Feng family home is hidden behind this relatively modest doorway.

The Main Hall is furnished and decorated as it would have been early in the twentieth century when the Feng family occupied it.

When thrown open on their pivots to link interior and exterior spaces, the richly carved doors serve as an ornamental feature.

View under the projecting protective eaves that shelter the carved wooden lattice panels of the living quarters in the second courtyard of the Feng residence.

Close-up of a shallow carved panel of the door shown to the left. Five intertwined bats, which have a homophonous relationship with the word fu for good fortune, represent the “five good fortunes,” namely, longevity, wealth, health, love of virtue, and to die a natural death in old age.