Set within a green copse of bamboo, the Deng family yuanzi or courtyard is an inverted U-shaped building of substantial proportions. As a relatively symmetrical sanheyuan or “three-enclosed courtyard,” it includes a pair of perpendicular wing buildings flanking the main horizontal building.

After the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, no Chinese has loomed larger than Deng Xiaoping. The two had worked together but also against each other, intensively and intermittently, in giving shape to Communism in China over six decades. Yet, it was Deng, once a committed disciple of Mao, who, when he ultimately emerged from Mao’s shadow, articulated gaige kaifang (reform and opening)—Socialism with Chinese Characteristics—a host of economic and social policies that then accelerated China’s remarkable transformation over the past quarter century.

Born in 1904, eleven years after Mao, and living a little more than two decades after Mao’s death in 1976, Deng’s 92-year life essentially ranged across the full length of the twentieth century. In some ways, Deng’s journey from the remote interior province of Sichuan to the world stage paralleled China’s own passage from the isolation of the Middle Kingdom to a looming global presence at the beginning of the twenty-first century. His own rural family clearly embraced old ways while at the same time urging the young Deng to raise his eyes and look beyond his remote village for new opportunities.

Mao’s birthplace in Hunan province became a much-visited revolutionary shrine during the Great Helmsman’s lifetime, whereas Deng’s childhood home in Sichuan remained essentially unvisited until recent years. Deng himself never returned to the house of his birth after leaving it as a teenager, never visited his parents’ graves, and, according to his daughter, “did not allow us to do so either, on the grounds that our arrival there would disturb a lot of people as well as the local government.” Yet, just as others were beginning to discover his quiet home village, Deng’s daughter Maomao and his younger sister Deng Xianfu visited the Deng family homestead in October 1989, seemingly more out of curiosity than any attempt to search for family roots.

A Sichuan proverb says, “When the sun shines in winter, the dogs bark.” Especially from October to March, days are often gloomy, the sky is gray, the sun is hidden, light rain falls, and temperatures are mild, with the result that vegetation remains lush. Often wreathed in clouds, northeastern Sichuan is a region of jade-green hilly landscapes, its well-tended fields a veritable mosaic of rice, vegetables, corn, fruit, mulberry, and bamboo. The region boasts a long history of intensive farming but only relative prosperity. With a year-round growing season, three crops traditionally were the norm and, as a result, hardworking farmers generally were able to eke out at least a comfortable life for their families. The young Deng was born on August 22, during summer, when the sky was clear and temperatures intensely hot.

The ancestors of Deng Xiaoping had been in Sichuan for many generations, some say for 600 or 700 years, most likely arriving as migrants from Jiangxi downriver because of turmoil. Like other lineages whose members can be traced over long periods, those who passed the civil service examinations and became “officials” usually receive the most attention from their descendants. One or two family members many generations removed from Deng Xiaoping had passed the highest jinshi degree and been named to the Hanlin Academy in the imperial capital during the Qing dynasty. Indeed, the name “Paifang village” proclaimed the presence of a multi-tiered memorial arch or paifang commemorating such an ancestor during the eighteenth century. The arch was smashed during the Cultural Revolution, and the name of the village itself was changed to Fanxiu xiaodui or “Anti-Revisionist Production Brigade,” a label it carried until the early 1980s.

Taken in France two years after he left his Sichuan village, this studio photograph shows Deng at the age of sixteen.

Both the broad courtyard and the dwelling itself are raised above the surrounding area and are accessible by a series of stone steps.

Nearly two meters in depth, the front verandah is covered by a broad overhanging roof that is supported by a tier of projecting tie beams of different lengths.

Some of the vertical supports for the projecting tie beams are carved as ornaments.

The ancient phrase shan gao, huangdi yuan (“the mountains are high, the Emperor is far away”) describes well the Sichuan countryside at the end of the Qing dynasty. Villagers lived relatively self-sufficient lives, with both the strengths and constraints of family tradition, and were linked to the outer world only via the market town in which peasants, merchants, and others mingled on periodic market days according to cyclical dates. Complementary spheres of work, succinctly stated as “men plow, and women weave,” not only made it possible for families to be essentially self-reliant but allowed the amassing of modest wealth if cash income increased.

Farming, domestic handicrafts, petty trade, and service as village leaders likely provided the Deng family the means for economic progress over time. Certainly, they never became wealthy because of land holdings, merchant trade, or high office. Increasing wealth supported improvements to the family dwelling as well as education for the children, but the circumstances relating to how the U-shaped farmhouse took shape are lost in the fog of history.

Paifang village, like other villages in Guang’an county, still has a dispersed pattern of rural settlement. Instead of villagers living together in a compact rural settlement of tightly packed dwellings, approximately a hundred households in Paifang inhabit housing clusters loosely dispersed along a stream. The stream, villagers say, helps bind separate families to membership in a single village. In Sichuan, each of these diminutive hamlets is called a yuanzi, often translated as a “courtyard.” But each is much more than an open space surrounded by structures, since a yuanzi may include several actual courtyard-type dwellings. Delineated and protected by a dark green circular grove of bamboo, each dispersed yuanzi is rather secluded and appears to float amidst the extensive terraced paddy fields.

Only a few essential facts are known about Deng family circumstances as the twentieth century dawned. Many particulars remain conjecturable, in part because of the later political vicissitudes of Deng Xiaoping himself. His father, Deng Shaochang, was born in 1886, probably in the same hamlet in which he was to raise his own family but possibly in a smaller dwelling. When he himself was a young boy, Deng Shaochang lost his own father, who left behind a widow, who was mother to at least two children, including an elder daughter, and head of household with several additional family retainers.

While this small family of the Deng grandfather cannot account for the extensive dwelling seen today, it probably was the serial conjugal activity of Deng Shaochang, the father himself, that led to its construction. When Deng Shaochang was about thirteen, he took a young wife who, by marrying in, replaced his sister who had married out to a family in another yuanzi. The young wife, however, proved barren and Shaochang sought another woman, some describe as a wife from a wealthier family but others say was merely a concubine required to increase the probability of a much hoped for son. In any case, this woman, surnamed Dan, gave birth in 1901 to a daughter and then three years later a son, first called Xiansheng, then Xixian, among several other names, and then later Xiaoping, the name he carried during his adult life. Two other sons were subsequently born before Deng Shaochang brought two other women, more likely concubines than official wives, into the family courtyard where each required her own bedroom and support. The third woman gave birth to the fourth son of Deng Shaochang. The fourth woman brought into the family as a wife, Xia Bogen, was a young widow with a daughter who then gave birth to three other daughters.

As this plan shows, more than half the rooms in the Deng home were bedrooms, a pictogram suggesting the complexity of multi-generational family life during late imperial times. Some other large rooms provided space for looms that were used for the production of textiles.

Today, the tidied up Main Hall of the Deng residence barely suggests the formality and activity that would have characterized it at the beginning of the twentieth century.

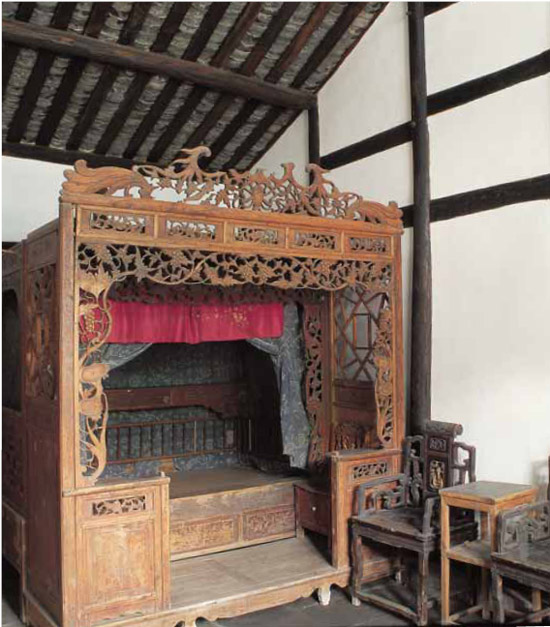

The old ostentatious furniture described as belonging to Deng Xiaoping’s parents actually replaced plainer furniture seen in the house a decade earlier. It is unlikely that what is shown originally belonged to his parents.

Even in the late 1990s, the Deng farmstead essentially stood alone within a traditional agrarian landscape but has been transformed in recent years. In preparation for the centenary of his birth in 2004 and expectations of increasing visitation, a vast interpretative Deng Xiaoping Memorial Park has been created around the farmstead.

As a testament to what might appear as fluidity in Chinese family structure, Deng’s own daughters considered this fourth wife as their grandmother, who after 1949 came to live with the Deng family in Beijing. During Land Reform in the early 1950s, various local peasant families, including some cousins, were given spaces in the old house to call their own, and some continued to occupy the house until the late 1980s when the dwelling was emptied out and tidied up. Today, only cousins of Deng remain as representatives of the family’s origins in Paifang village. The rambling house, with its twenty rooms, is at once a pictogram representing fecundity during late imperial times while remaining strikingly mute about the memories it holds within it.

The rapid growth of Deng Xiaoping’s father’s “family,” undoubtedly acceptable in terms of traditional norms, came to be accommodated easily in what must have been the most impressive house built in a village where most farmhouses were mere three- to five-room rectangular structures with thatched roofs. During the decade when his family expanded with “wives” and children, Deng Shaochang did little farming, depending more on hired laborers and increasingly spending time as a leader of local organizations, all of which is clear evidence of his increasing power and wealth.

Whether Deng Shaochang was “a cruel landlord, who lived the life of a parasite sucking the sweat and blood of poor peasants” or “a good man, hard-working by himself and sympathetic to others” depends upon whether the evaluation was made by Red Guards in the late 1960s when Deng Xiaoping was a political pariah or in the 1980s after he had been politically “rehabilitated” and became “Paramount Leader.” In any case, Deng Shaochang provided an imposing farmhouse for his changing family as wives arrived, babies were born, and children grew. A tutor was hired for the eldest son, the young Xiaoping, as he was later to call himself. The lad was enrolled in a primary school outside the village in 1910, where he studied for the next five years, before being sent off to a boarding school in Guang’-an county town some 10 kilometers away. In 1918, a few days after his fourteenth birthday, he and his slightly older uncle left China for France, by way of Chongqing, Shanghai, and a thirty-nine day ocean voyage. With his father’s blessing, they were participating in a work–study program that came to involve some 1500 young Chinese between 1918 and 1920.

In a corner of the grandparents’ bedroom is an ornamented canopy bed.

Characteristic of dwellings in this part of eastern Sichuan are walls composed of white infill panels set among slender pillars and multiple trans-verse tie beams that make up the wooden framing system called chuandou.

It is said that the young Chinese sojourners hoped more to “study” but the French wanted them more to “work,” yet both work and study in a foreign land proved transformative for those who participated. Effectively abandoning his boyhood home and family, Deng Xiaoping indeed embarked on a remarkable journey to the pinnacle of power in China. Remaining in France for more than five years, he worked longest as a laborer in the Schneider & Cie Iron and Steel ordnance factory in Creusot. He also worked as a fitter in the Renault factory in a Paris suburb, as a fireman on locomotives, and as a kitchen helper in restaurants. Throughout this period, he came to meet and know other young men who subsequently became well-known Chinese Communist leaders. Among them were Zhou Enlai, Jiang Zemin, Zhu De, and Chen Yi. Now more aware of China’s ferment, even though a continent away, and attracted by Marxism, many of these work–study youths, including Deng, joined the fledgling branch organizations of the Chinese Communist Party while in Europe. In January 1926, he went to Moscow to study and then returned to China in early 1927. In July of that year, he met Mao Zedong in Wuhan. It was at the age of twenty-three that he changed his name to “Xiaoping.”

It appears that Deng Xiaoping never seriously pondered the circumstances of his early life in Sichuan, either to acknowledge the fortunate paths set for him by his father or to contemplate what his own life might have been like if he had not left. Meanwhile, his father continued to gain status as a member of the village élite and a commander of a regional security force, living until 1936 or 1938. It is said that Deng Xiaoping sent revolutionary pamphlets home and his father sold some land to provide funds for his eldest son’s revolutionary activities.

The open U-shaped courtyard dwelling of Deng Xiaoping’s boyhood can be described as a sanheyuan or “three-enclosed courtyard,” somewhat similar to others in southern China, yet it has striking Sichuan characteristics. In Sichuan, inverted U-shaped houses are called sanhetou, which has a similar meaning to sanheyuan. They are raised above the ground, their rubble stone base supporting a stone foundation that requires several sets of steps. All open areas probably were originally made of pounded earth although over time stone slabs were used to surface the courtyard, floors, and verandahs. Such improvements entailed significant expense.

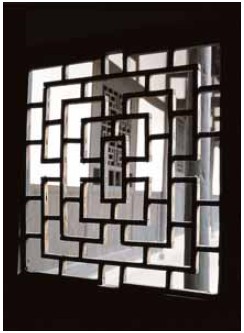

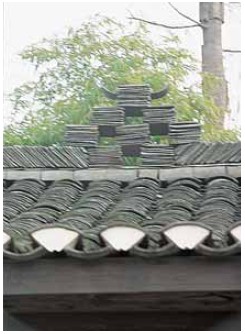

A pair of wing buildings flanks the main building; space is symmetrical and generous in both extent and volume. Comprised of a horizontal building joined with a pair of perpendicular wings, space is clearly delineated in relatively large, high, deep, and airy rooms for a range of activities characteristic of a prosperous farmstead. The rooms in the main structure are all much taller than those in the wings. Buildings of this type have a wooden framing system called chuandou, consisting of slender pillars that are tied together with multiple transverse tie beams. The latter are similarly slender in dimension yet serve to stabilize the structural framework. Each pillar is set on a simple stone base or on the encircling stone plinth within the interior walls. The weight of the heavy tile roof is carried to the ground directly by the pillars. In order to create a broad verandah ringing the dwelling, the roof is extended via the use of substantial eaves supported by protruding horizontal tie beams. Although mortise-and-tenon joinery is seen everywhere on the outside of the house, it is most outstanding on the overhang framework that supports the eaves across the front. Nearly two meters in depth here, the weight of the roof tiles requires a tier of projecting tie beams of different lengths in order to bear the load. Even during heavy rain, the front verandahs allow the large lattice windows to be left open for ventilation against oppressive heat.

The unvarnished natural patina of wooden pillars, wainscot paneling, and lattice window frames provide a contrast to the whitewashed infilling between the columns. The complicated and costly wooden structural framework is a statement that the owner is prosperous. Each infilling between the pillars is a nonload-bearing curtain wall made of split bamboo culms woven into panels and then sealed with a mud or mud-and-lime plaster before being whitewashed and made impervious to air and moisture.

Little of the house has been interpreted except for the Main Hall, kitchen, parents’ bedroom, grandparents’ bedroom, Deng Xiaoping’s own bedroom, and the large grain-processing area in a corner room. The original family furniture indeed was scattered over the years, replaced after 1949 by what was needed by the nearly dozen peasant families who occupied the space. By the late 1980s, several old wooden bedsteads, some square tables and benches, as well as paired side chairs and tables, accompanied by some photographs, calligraphy, and household ephemera, had been installed in the newly empty rooms. They failed, however, to give any sense of the daily life that must have once been common in the Deng yuanzi a century ago. In recent years, a few pieces of ostentatious furniture have replaced plainer ones seen a decade earlier. Most noticeable are the large old beds seen in early 2004 that are more likely to be of the type used by a prosperous rural family than the simpler ones in the house in the 1990s. Whether they have any connection with the Deng family is indeterminable.

There are large empty rooms that were probably once used for the household economy, especially the production of textiles. This type of handwork is said to have interested Deng’s mother and, as a cottage industry, was likely a source of additional income for the family. Textile production in Sichuan meant both cotton and silk. Sericulture entailed a lengthy process involving many stages and bulky equipment such as bamboo racks, feeding trays, reels, and looms. No such equipment is evident in the farmhouse today. Raising silkworms, especially, was a labor-intensive activity since great care was required to satisfy the voracious appetite of the silkworms and to regulate the temperature, humidity, light, and noise that affect their development. Family members recall the courtyard being filled with chickens and geese, which were raised principally to guard the house because they made loud noises when strangers approached and were known to be almost as fierce as dogs.

Until the late 1990s, the farmstead essentially remained as a solitary and silent connection with Deng’s remarkable life. However, with the centenary of his birth in August 2004 and expectations of increasing visitation, a vast interpretative Deng Xiao-ping Memorial Park, weaving the natural setting of terraced fields and ponds with a wealth of interpretative facilities, has been created. These include an exhibition hall and theater, a reconstructed paifang or memorial arch, an array of memorabilia including the old family well, and even the black open-topped Red Flag limousine Deng used to review the troops parading in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square.

Anchoring this park is Deng’s boyhood home, which provides only vague hints of the early life of this remarkable leader. Yet, significantly, the preserved birthplace represents a type of fine dwelling once found throughout this region where houses still are “of the land and the people.” In their form and structure, they reveal accommodations to climate, available building materials, and the cultural dynamics of families that live in them.

Along the front and side verandahs, large, relatively simple lattice windows provide ventilation for the interior in an attempt to reduce the often oppressive heat and high humidity.

The stacking of thin roof tiles along the ridgeline not only offers ornamentation but also serves to stabilize and seal a critical seam where two slopes join on the roof.