Shanxi province has some of China’s grandest manors of the Qing dynasty and, by contrast, some of the simplest dwellings from the Ming dynasty. They are spread rather randomly in what appear to be desolate areas of central and southern Shanxi, but their locations point to old trade routes and optimal settlement sites whose nature is not yet fully understood. In the case of grand manor complexes, their presence hints at a level of merchant culture and wealth in the past that seems anachronistic today given the prominence of dirty industries such as coal-mining and cement-making, which plague the province with leaden skies filled with cough-producing soot. Yet, today in China, where “making money” through commerce and entrepreneurship are touted as the engines of economic development, it should not be surprising that a new focus is being put on the country’s commercial history as well as on surviving residential architectural gems of wealthy families in the past.

The study of China’s long-distance merchant networks is still in its infancy and there are many gaps in our understanding of the respective roles of private individuals and the imperial state in the economy’s rise and fall over five centuries. Even less is known about the specific circumstances leading to the design and construction of extensive residential manors in far-flung areas. Some of the earliest merchants gained wealth in the lucrative salt trade. Later on, iron, cotton, soybeans, tea, and silk became part of the trade mix, and by the nineteenth century individuals grew rich from pawnshops and banking. During the Ming dynasty, “Shanxi Merchants,” called Jin Shang using the conventional abbreviation for the province’s name, amassed wealth by transporting grain to feed troops along the northern Great Wall frontier and from licenses entitling them to sell salt at monopoly prices. Long-distance trade of this sort, especially along the borders with Mongolia and Russia, expanded between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. Just as “jumping into the sea” (xia hai) today suggests danger as well as opportunity for Chinese entrepreneurs who explore uncharted territory, in Shanxi, during the Ming and Qing dynasties, zou Xikou or “going to Xikou” meant trekking beyond the Great Wall to find potentially lucrative prospects not available at home.

The Lu Ban jing carpenter’s manual spells out not only the dimensions of an efficacious Taishan shi gandang (“resisting stone”) but also the time when it should be carved and then set in place.

With the five characters Taishan shi gandang and a threatening animal face chiseled into its flat face, this defensive stone is placed on a wall at a T-junction where one lane reaches another outside the Qiao family manor.

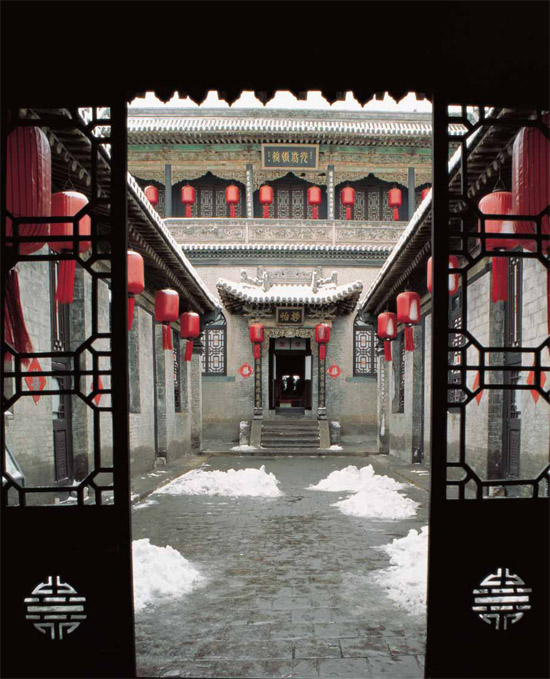

The approach to each courtyard complex in the Qiao family manor is through an imposing entryway constructed of brick, wood, and tile.

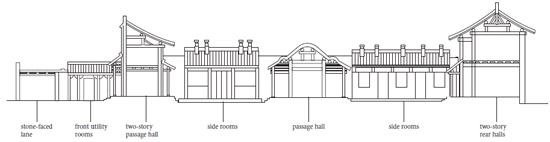

Section view of the Qiao family manor from south to north (left to right) showing the three main horizontal buildings, including a two-story structure in the rear, and the perpendicular structures that together form sets of courtyards.

Most of the residential complexes of Shanxi merchants are walled and located within villages or towns in what today are considered remote locations. Few provide obvious evidence of the economic and social factors that contributed to their formation over a period of several centuries, especially during the prosperous seventeenth and eighteenth centuries but even continuing during the less flourishing nineteenth century that followed. Each is usually designated as the dayuan or zhuangyuan (manor or estate) of a single family or clan. It is said that there are seventeen such manors in Qixian county alone and perhaps as many as a thousand scattered throughout the province. Although some have deteriorate markedly over the last two centuries because of neglect, natural forces, as well as deliberate destruction, others remain remarkably intact and beautiful, providing clues to past social and economic forces that are evident in no other way. In recent years, local boosterism has brought many of these to light, but only a handful have been extensively renovated and promoted, especially the manor complexes of the Qiao family, Qu family, and He family in Qixian county, Jiang family of Yuci city, Wang family of Jingsheng village in Lingshi county, Shi family of Shijiagou village in Fenxi county, and Cao family manor in Beiguang village in Taigu county.

Fortified residential complexes usually are an architectural response to unsettled conditions. In China, rebellion, banditry, and the general turmoil associated with the change of dynasties usually led to the building of high walls in order to provide security. In many cases in Shanxi and other parts of northern China, village walls were rather temporary forms made of earth that survived only as long as there was a clear purpose for them. When they were no longer needed, they were razed as stability replaced strife or eventually nature would obliterate them. In cases where the wealth of affluent clans made it possible, substantial fortifications of fired brick and stone, with parapets, towers, and sometimes moats, were built around existing as well as new settlements. Once completed, walled residential complexes of this sort were generally preserved as markers of a clan’s strength and power. In Shanxi, walled villages and residential complexes are often called baozi or bao “fortresses,” toponyms that remain even in the absence of the fortifications themselves.

This decorative door panel incorporates a pair of complementary motifs: bats, which are homophonous for “good fortune,” and a stylized longevity character.

Far right: Ornamental brass door loop in the shape of a flower vase, the sound of which is homophonous with “peace.”

View from the first courtyard through the passageway structure into the second courtyard, and the two-story structure that constitutes the rear or upper hall within the Qiao family manor.

Qiao Family Manor

Widely regarded as an outstanding example of a bao is Qiaojiabao, the grand fortified settlement of the Qiao family in Qixian county. Begun in 1756 by Qiao Guifa, the Qiao family manor or Qiaojia dayuan came eventually to occupy a total area of 8725 square meters as a result of two major expansions, one in the middle of the nineteenth century and then again at the beginning of the twentieth century just as the Qing dynasty was ending. The Qiao family thrived from trading activities centered at Xikou, today called Baotou, beyond the Great Wall in what is now Inner Mongolia. Specializing in trade in pigments, flour, grain, soybeans, and oils as well as running several pawnshops, the Qiao clan prospered, eventually expanding their business far beyond the borders of northern China. By the end of the nineteenth century, they operated coalmines, specialized shops, and an extensive banking network. Empress Cixi stopped at the Qiao family manor in the summer of 1900 as she fled to Xian with the young emperor in the wake of the arrival of an international expeditionary force in Beijing at the close of the Boxer Uprising.

Changes in the national economy in the first decades of the twentieth century reduced the family’s income and, according to popular beliefs, the profligacy of the fifth-generation descendants of the clan’s founder led to bankruptcy of the clan. By the early 1930s, the family had divided up its assets and the manor began to fall into disrepair, finally being abandoned after the Japanese invasion in 1937. After 1949, the complex was taken over by local authorities who used it as an army barracks as well as for other governmental functions. Substantial destruction occurred during the Cultural Revolution. In 1985, the manor’s fortunes, if not of the clan, turned again as the complex was designated a museum with substantial funds apportioned for its repair. The grandeur of the Qiao family’s dayuan is apparent to viewers of Zhang Yimou’s 1991 film “Raising the Red Lantern.” Zhang’s story is one of deceit, treachery, and sexual favors in a wealthy Chinese clan at the beginning of the twentieth century—all occur-ring within the confines of a grand feudal mansion. His tale, however, is not that of the Qiao family whose rise and fall is itself worthy of being told.

As the manor complex took form, gray brick outer walls were built to connect the even higher back walls of courtyards. Capped with parapets, these 10-meter-high walls without windows presented a formidable and secure enclosure for the Qiao family. Because the manor is approached via narrow village alleys and never viewed from afar across the fields, its overall scale appears even more imposing as one encounters its main gate because of the height of the adjacent brick walls. Atop some of the flat roofs, several tall towers were built to rise high above the walls so that patrolling night watchmen could survey the inside and outside of the complex from passageways and steps that circuited the complex. Just inside the front gate, an east–west running lane paved with stone leads to the ancestral hall at the end and the courtyards making up the manor. In order to meet the needs of a large and growing extended household, the manor complex eventually came to comprise six major courtyard compounds, three larger ones on its north side and three smaller ones on its south side. Each set of steps leading to the gate of one of the six courtyard complexes is entered from the east–west lane and each of the steps and gates is staggered so that it is not directly opposite another. Near each of these entries are stepping stones to assist riders on horseback as they mount and dismount. Some say that the layout of the courtyards, rooms, and lanes auspiciously resembles the character for “joy.”

“joy.”

View towards the inner portion of the east–west lane that separates the three larger courtyards on the north from the three smaller ones on the south.

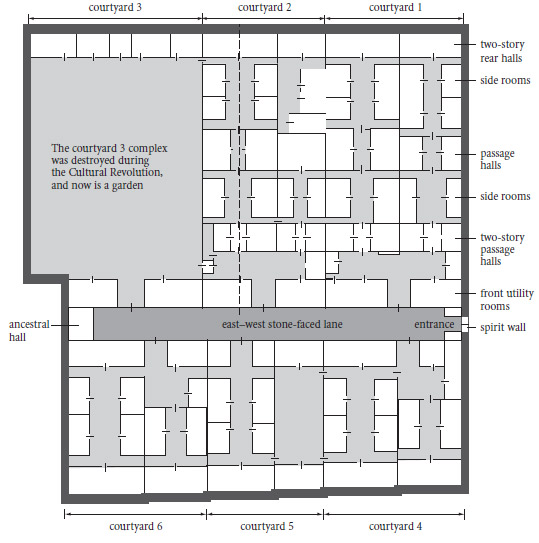

The blank space in the northwest corner of this plan was once a large courtyard complex that was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Beyond it are the outlines for buildings and narrow open spaces that make up the Qiao family manor’s remaining two multiple courtyard complexes on the north and the three smaller ones on the south.

Beyond each of the entry gates to the six courtyards on the north and south sides of the lane is a complex of twenty smaller courtyards and side yards as well as 313 enclosed rooms with a total floor space of 3870 square meters. On the north side, only two of three sets of courtyards remain. Courtyard 3 in the northwest corner was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and has been replaced with a garden. Of the two remaining courtyards on the north side, each has an east to west entry courtyard as well as several narrow rectangular inner courtyards that run north to south. The oldest is Courtyard 1, called laoyuan or “the old courtyard,” which was built in the mid-eighteenth century by Qiao Guifa.

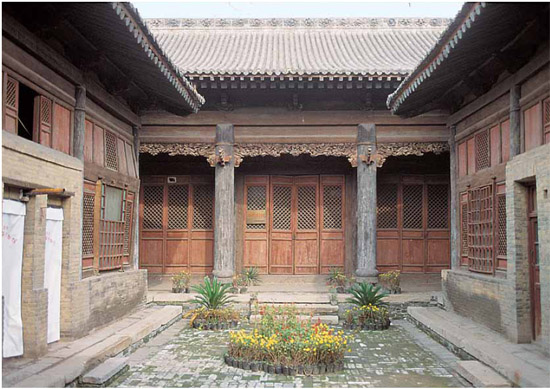

Once past an entry courtyard that runs east to west, there are two narrow inner rectangular courtyards that run north to south that are linked by a hall. Midway between these two longitudinal courtyards is a single-story guoting or ”transitional hall” with a rolled roof that leads to a dramatic courtyard framed by side buildings with somewhat curved roofs. On the north side of the second courtyard and entered through an elaborate gate is a two-story zhengfang or main structure. Called here an “open or bright building” or minglou, it faces south and has a sweeping double-sloped roof-line. Although five bays wide, the minglou has no internal partitions so that it can be used as a single room. Its second story cannot be accessed directly via an inside stairway but can only be entered from an adjacent rooftop. Unlike elsewhere in northern China, the Qiao family used its zhengfang exclusively for ceremonial purposes such as making offerings and welcoming guests. Five-bay-wide side buildings, called xiangfang, run north to south alongside the narrow inner courtyard, and contrast with three-bay- wide xiangfang in the outer longitudinal courtyard. Although perpendicular to the minglou, they are not physically joined together. Both side structures have single steeply pitched roofs at a 45-degree angle that rise higher on the outer wall in order to dampen the impact of winter winds and then lead rainwater into the courtyard. Household members used the xiangfang or side rooms for daily activities such as eating and sleeping. Inclined towards the interior and with a prominent eaves overhang, the lower roofline of these side halls creates a human scale for the otherwise constricted courtyards and surrounding high walls, providing at the same time a sense of openness that belies their narrow shape and diminished size. Internal passageways with open portals provide corridors around the complex for women and others who need not enter the main courtyards and gates.

What appears today as a pleasant garden represents the filling in of vacant space left over after the destruction of the courtyard complex during the Cultural Revolution.

Axonometric drawing of a Ming-dynasty house in Dingcun, the Ding family village, showing a tight plan of built structures and open spaces.

The slightly irregular quadrangular plan of a Ming-dynasty dwelling includes two pairs of facing structures, with the paramount one placed to the north and facing south.

The high exterior walls helped to buffer winter winds while the inclined roofs drew sunlight and rain into the narrow courtyards. The use of elevated and curtained beds instead of heated kang by the Qiao family is at variance with general northern practices that provided winter warmth from the radiated heat of kang upon which members of the family would spend much of the cold winter. Much of the Qiao family complex, however, was heated by a more expansive system that involved extravagant consumption of fuel necessary to keep whole rooms warm, clearly expressing the wealth of the household. This was accomplished by linking large stoves to chimneys via a warren of flues that ran under the brick floors and through some walls in order to supply radiant heat from many directions. As a result, more than 140 chimneys, some of which are elaborately ornamented, populate the upper walls and roofs. Except for the embellished exterior entryway that faces a wall with 100 variations of the Chinese character for longevity carved on it, brick, wood, and stone carvings were limited to inside locations that only the family could experience. Around 1921, renovations introduced Western-style ornamentation as well as modern features such as bathrooms, electricity, and etched window glass without changing the traditional character of the residential structure.

Ding Family Village

Perhaps the oldest residences in Shanxi are those in Dingcun or “Ding Village” in Xiangfen county. Of forty designated structures, ten have halls and courtyards that were built in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries during the Ming dynasty with two complete dwellings said to date to the Wanli period (1573– 1620). The earliest siheyuan, dated to 1593, is located in the northeast part of the village and preserves characteristics of Beijing-style residences: an entry gate on the southeastern wall, a spirit wall, a rear-facing daocuo, a colonnaded south-facing three-bay-wide main hall, a pair of flanking side rooms three bays wide, and brick kang beds.

The second oldest, dating from 1612, was built with two courtyards and associated structures, but today only fragments remain. Some dwellings may be older although they have undergone such modification that they do not represent Ming styles. For the most part, Ming dwellings are characterized by relatively simple siheyuan quadrangles that conform to the sumptuary regulations of the times.

While some of the Qing-period dwellings in Dingcun are uncomplicated, others involve receding and interconnected courtyards with substantial attention to hierarchy and the separation of outer and inner realms. Local historians attribute the survival of fine examples of Ming and Qing dwellings not only to the remoteness of Dingcun from the past centuries’ tumult but also to family inheritance practices that demanded shared ownership. When two brothers divided their father’s real estate, one would take an “upper” share and the other a “lower.” This horizontal division worked against any one individual’s desire to demolish and rebuild without the consent of the other. In 1985, six contiguous dwellings built between 1723 and 1986 were designated as the “Dingcun Folkways Museum,” reputedly the first such specialized museum in China.

Looking north towards the three-bay Main Hall of a Ming-era dwelling in Dingcun village. The pair of flanking side buildings faces a narrow courtyard that is ringed by elevated stone-work sheltered by a broad eaves overhang.