Among the least-known, largest, and most interesting manors on the loessial plateau in Shanxi province is that of the Wang family, once one of the four most powerful families in Shanxi and the ancestors of Wangs who today live throughout China. The Wang-jia dayuan or Wang Family Manor extends across a gentle loessial terrace along the slopes of Mianshan Mountain in Jingsheng village, some 12 kilometers from the small county seat of Lingshi and 150 kilometers south of the provincial capital Taiyuan.

Wang, romanized also as Wong in Cantonese, Heng in Teochew, Ong in Hokkien, and Vong in Vietnamese, contends with Li and Zhang as the most common surnames found in China. Together these three surnames are held by more than 270 million Chinese—nearly equaling the total population of the United States—with each of them representing about a third of this number. Today, the Wang surname belongs to more than 10 percent of families in north China, while it is only second in the Yangzi River region, yet does not rank even in the top five in southern China. Meaning “king” or “ruler,” Wang, according to many authorities, originated as a surname in central Shanxi province during China’s first unified dynasty, the Qin, in the third century BCE. As one of China’s oldest family names, it thus has its roots in northern China, with a complicated dispersion history throughout the country and indeed in Chinese diasporas around the world.

There are detailed records that trace the arrival of the Wangs from Taiyuan to Jingsheng village in 1312 during the Yuan dynasty. According to legend, the family began to supplement its farming with income derived from the making and selling of bean curd, an enterprise that enriched the family over time. These humble origins are highlighted today in the descriptive exhibits in the manor, but it was business, trade, and official position that eventually brought greater wealth. The eighteenth century is always highlighted as a peak in the Wang family’s development, since it was during this century that resources and talents accumulated to such a degree that large residences, ancestral halls, as well as private academies were built. The family used its wealth also for public benefit by building roads, bridges, water conservancy projects, public granaries, opera stages, and temples. Moreover, the Wangs built a Confucian temple in Jingsheng village, a rarity in China’s countryside, which served as an academy for educating young boys, leading many of them to success in civil examinations. Yet, as the Qing dynasty itself waned in the nineteenth century, the Wang family’s fortunes in Shanxi also declined, according to family histories, for many reasons, including profligate and self-indulgent sons. Some claim that by 1949, most of those surnamed Wang had abandoned Jingsheng, their home village, leaving for Beijing, Sichuan, Taiwan, and even the United States.

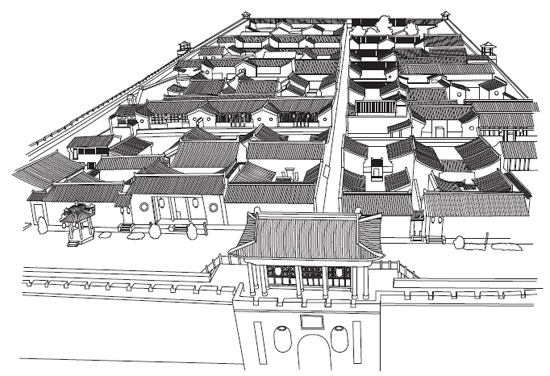

Bird’s-eye view of a major portion of Hongmen Bao, the “Red Gate Fortress,” revealing the impregnability of its eight-meter-high encircling brick-faced wall and the complexity of receding and interconnected courtyards.

The single south-facing gate, colored red, is the source for the name Red Gate Fortress and leads to a 3.6-meter-wide north–south lane.

As shown in this plan, the north–south lane is crossed by three east–west lanes in order to represent auspiciously the Chinese character for Wang, the family’s surname.

One of the south-facing residential courtyards shows the cave-like main structure and abundant carvings as well as the pair of facing two-story buildings with upstairs rooms and balconies that provide private spaces for young women.

Each of the narrow side lanes is entered through a richly multitiered ornamented gate.

This carved wooden horizontal member extends beyond the balcony it supports.

Separated by roughly triangular-shaped dripping tiles, the circular tile ends are molded with protective totem-like animal faces.

In the village, it was said that among the so-called “nine gullies, eight fortresses and eighteen lanes”—cave dwellings, walled compounds, and compact village—“five gullies, six fortresses, and five lanes” belonged to the Wangs. Built first over a seventy-five year period in the seventeenth century, the full Wang family manor complex sprawls across nearly 32,000 square meters (eight acres), and is divided into two distinct eastern and western “fortress courtyards” or baoyuan, each with its own gate, as well as a separate Ancestral Hall complex. The east courtyards are collectively called Gaojia Ya or “High Family Ridge” and those on the west Hongmen Bao or “Red Gate Fortress.” The structures and courtyards in both complexes are arranged in ascending tiers on a hillside, with courtyards of various sizes and shapes aligned along several north–south axes running up the slope. With encircling walls, courtyards within courtyards, and numerous gates, the Wang family manor fits well with the terrain, offering at once protection from external threats and security for the extended family within. Facing south, the building complex has a commanding presence as it overlooks smaller village dwellings below it, even suggesting to some that its dominance is castle-like.

Within the four walls of Gaojia Ya, built between 1796 and 1811, the courtyards are arranged in six parallel tiers that rise along the mountain slope, with a gate at each of the four cardinal points of the walls. At the core of Gaojia Ya is a set of three courtyard complexes, each with a layout having the Main Hall in front and the bedchamber to the rear, with kitchens to their east and a school and garden on the west. Each of the courtyards is divided into three building units, comprising a zhengfang or main structure to the rear and a pair of flanking xiangfang built to look like subterranean dwellings, but which actually are above-ground cave-like dwellings called guyao. Thirteen actual cave structures, called yaodong, each with four attached courtyards, are found along the rear of Gaojia Ya where they have a commanding position overlooking the entire area. It was on top of these caves and inside the wall that watchmen patrolled at night to insure safety of the Gaojia Ya residential complex below.

After crossing a stone bridge over a deep gully serving as a kind of moat, the “western courtyard” complex looms large with its rectangular extent being 105 meters from east to west and 180 meters from north to south. With only a single south-facing gate, colored red, the Hongmen Bao or “Red Gate Fortress” complex is strikingly impregnable because of its encircling brick-faced wall, which rises eight meters on the outside but only four meters on the inside.

Built between 1739 and 1793, a time of great prosperity during the Qing dynasty, Hongmen Bao has a relatively simple layout: a single 3.6-meter-wide north–south lane is crossed by three east–west lanes, an auspicious shape that mimics the form of the Chinese character for Wang, the family’s surname. Set within this alignment are twenty-seven symmetrical courtyard units of various sizes. With encircling walls, courtyards within courtyards, and numerous gates, the Wang family manor fits well with the terrain, offering at once protection from external threats and security for the extended family within.

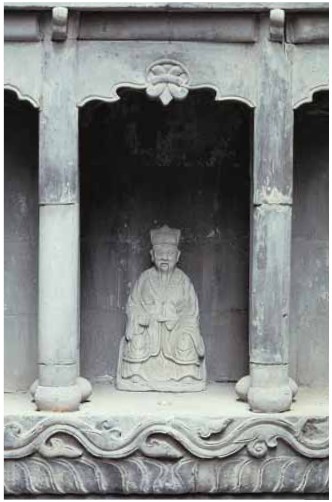

Tucked into a narrow alley, this grand niche for the Earth God is made of stone to mimic a building constructed of wood.

Seated at the center of the middle bay of his “home,” the tutelary Earth God is ready to accept offerings.

A craftsmen prepares new wooden carvings to replace those that are damaged.

According to Wang family legend, the layout of Hongmen Bao represents an auspicious dragon: the red gate represents its head; the two wells located at both the eastern and western ends of the lowest row are its eyes; the south to north lane represents the dragon’s body with the narrow lanes along the sides its claws; the luxuriant cypress towering above the fort in the rear is its tail. Throughout the courtyards of the Wang family manor, stone, brick, and wood-carvings, artistic and symbolic treatments of roof ridges, window frames, pillar bases, timber joints, and wall screens are especially noteworthy.

Clay chimneys throughout the Wang family manor are capped with pyramidal-shaped roofs with faux tile coverings.

Moral tales are among the most common themes of ornamentation throughout the Wang manor. Here, carved in bas-relief on the base of a column is a tableau portraying the well-known tale of filial piety in which a daughter-in-law provides nourishment of breast milk for her mother-in-law.

The restoration of the impressive Wang Family Manor began only in 1996. The initial challenge was the relocation of 212 households who had occupied its sumptuous spaces as squatters over the previous several decades, cluttering the courtyards and structures with the ephemera of everyday life and contributing to significant damage to woodwork and ornamentation. Teams of architects, engineers, and craftsmen then set out to clear the complex of damaged and decayed wood as well as disintegrated clay bricks and tiles. As part of the restoration process, some three million new bricks had to be fashioned of local clay in adjacent kilns and 3500 cubic meters of wood had to be obtained in order to overcome the accumulated decay of nearly two centuries of family and national vicissitudes.

Today, major efforts are being made to introduce those with the surname Wang anywhere in the world to the architectural magnificence of the Wang family manor in Shanxi, to have them learn of their noble background, mercantile acumen, and intelligence, but also to display for them the consequences of human failings. Moreover, there is optimism throughout Shanxi that the extensive renovation of the Wang manor complex and other historically significant residences, temples, and pagodas, as well as the establishment of sites noted for their natural scenery, will bring both tourists and ultimately prosperity again to the province. Shanxi is best known today for dirty coal-mining and industrial pollution. Yet, it seems likely that the richness of its architectural and historical treasures and its flourishing merchant and banking enterprises in which Shanxi merchants played such a dynamic role will contribute to increasing its recognition as an important center of culture.

This polychrome woodblock print tells the same tale of filial piety shown above in the stone carving, of a devoted daughter-in-law suckling her toothless mother-in-law.