Much of the region around Beijing is broad and flat, a product of deposition from the Huang He or Yellow River. Here, too, quadrangular siheyuan dwellings are generally level in their layout. To the north and west of the capital, however, are rugged mountains that provide not only the irregular landscape across which the traces of the Great Wall are draped but also the uneven building sites for tiny settlements. One such village is Chuandixia, a mountain village some 90 kilometers to the west of Beijing, in a vast, sparsely populated district called Mentougou in Zhaitang township. Migrants surnamed Han, from Shanxi province to the west, first settled Chuandixia during the Ming dynasty, in the early years of the fifteenth century, as they traveled through the difficult Taihang Mountains. Originally called “Under the Stove Village,” the complicated initial character for the village’s name  with thirty-one brush strokes, was formally changed in 1958 to the simpler three-stroke character

with thirty-one brush strokes, was formally changed in 1958 to the simpler three-stroke character  to mean “Under the Stream Village”—both pronounced Chuan.

to mean “Under the Stream Village”—both pronounced Chuan.

Seemingly isolated and remote, this tiny village, about two days’ journey from Beijing by foot or a day by horse, in time came to serve as an essential way station along an old post road that connected the imperial capital with Taiyuan in Shanxi province. The imperial system of postal couriers carried official documents between the far-flung outposts of the empire and the capital via a series of stations situated along the roads and paths that threaded their way through the mountain passes. Elsewhere in the country, the canal and river network served a similar function, but it was in the difficult mountainous areas that reliable rest stops were most critical. While villagers in Chuandixia were able to eke out a living tilling miniscule patches of sloping ground, supplemented by game killed in the wild, a significant proportion of their livelihood came from the food, rest, and water provided to weary couriers who passed by on foot or on the back of horses or donkeys.

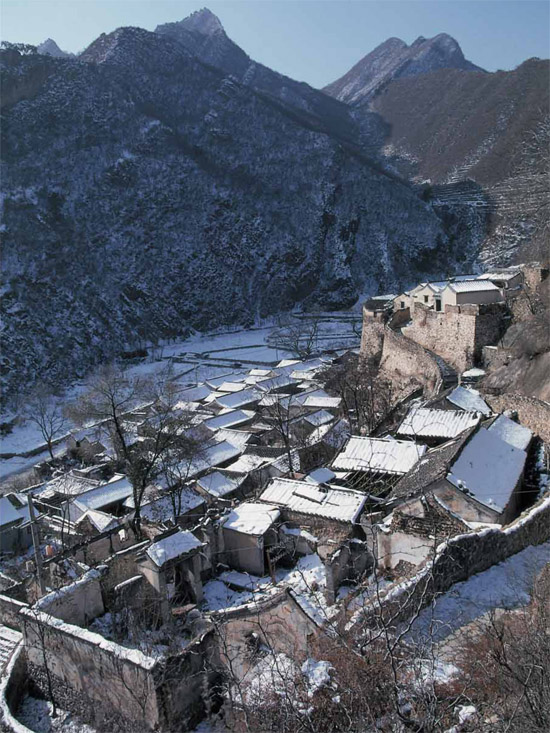

Because winters are bitterly cold in the mountains, the early settlers chose a building site for the village about 650 meters above sea level on the steep south-facing slopes. Here, the mountain to the rear provides a screen against the intense winds blowing from the Mongolian steppes, yet opens each of the houses on its south-facing slopes to the warmth of the sun. Rubble stones, abundant on the hillsides as well as sorted by water in the ravines cut by mountain streams, were the principal building materials for foundations, walls, paths, and steps. Timber for beams, purlins, windows, and doors, necessary components to complete the construction of their houses, was available nearby but only in limited dimensions and quantities. As a result, settlers were able to build only relatively compact dwellings to meet the requirements of limited building sites, available materials, and their own modest needs. While the earliest dwellings were probably constructed along the road, experience most likely showed that sites higher on the slope had the advantage of longer periods of sunlight, especially in winter. In time, an upper cluster of houses, linked to those below by stone steps and pathways, developed, which had to be buttressed from below by a 20-meter-high stonewall. The layout of stonewalls and paths also helped stabilize the slope in order to mitigate the consequences brought on by heavy summer rains. Residents claim that the village was “designed” for the convenience of people, cats, and dogs, each of which has its own narrow stone-lined pathways that allow them to move with ease from one level to another.

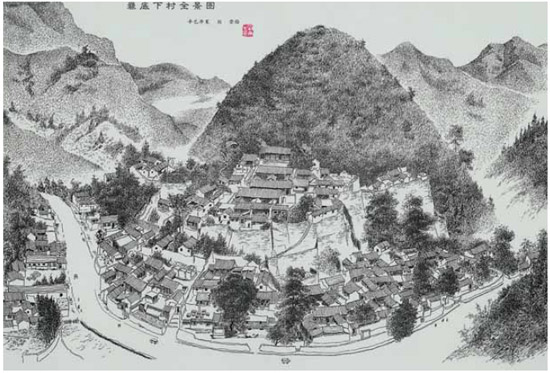

This contemporary drawing by Liu Chong reveals how the dwellings in Chuandixia village are arrayed across the steep slope, enabling villagers to take advantage of the winter sun and summer breezes as well as protect them from the cold winds that blow from the north.

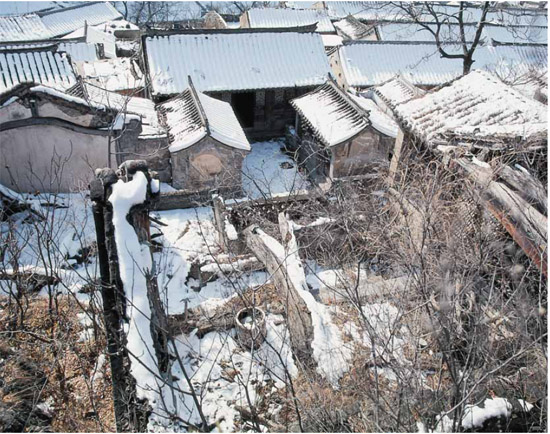

Draped across south-facing hill slopes, Chuandixia village is comprised of several sections at different elevations.

The topography enforces the building of interrelated parts of a single siheyuan on different levels. Connected by steps, the most important building is in back and is higher than the other related structures.

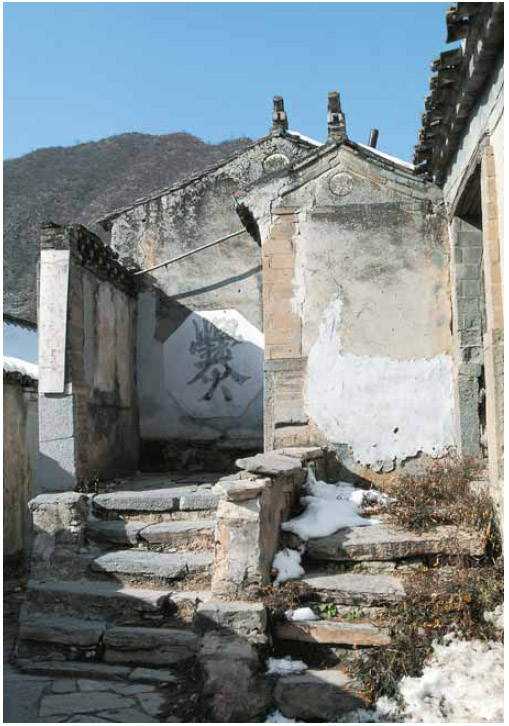

Painted on the wall at the entrance to the village, the complicated thirty-one brush-strokes’ character for chuan, meaning “stove,” represents a shorthand form for the name of Chuandixia village. This character was formally changed in 1958 to a simpler three-stroke character meaning “stream.”

Supported by a substantial stone foundation that rises some five meters above the steps below, this small house is connected to others by stone steps and pathways.

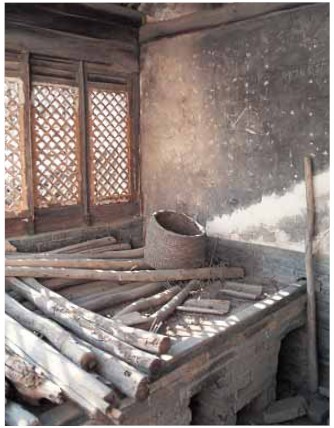

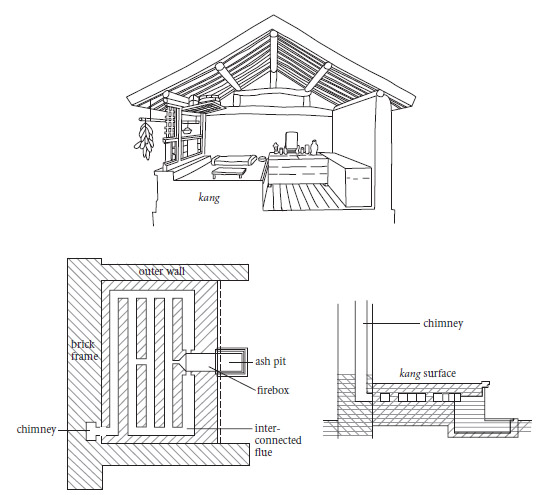

A kang or brick bed is usually built just inside the south-facing windows so that those sitting on it in winter benefit from the warmth of the sun’s rays. Additionally, each kang is a radiating surface in that heat from the firebox passes through it on its way to the chimney, in effect then warming the whole room.

Practical requirements of upslope building sites lent themselves to layouts in which each siheyuan was stepped into the hill slope, with back structures being higher than lower structures. Entry from a lane was usually first into a lower front level of the dwelling and an adjacent courtyard, with a series of steps then leading to a higher-level back structure and courtyard. Houses in the lower village generally are more level than those higher on the hill slope. Guang Liang Yuan, “The Luminous Courtyard,” the largest residential complex in Chuandixia, has three sets of stepped buildings with five meters of elevation separating the lower from the upper portion. Now undergoing restoration, it is surrounded by many other smaller U-shaped and quadrangular-shaped residences in various states of decay.

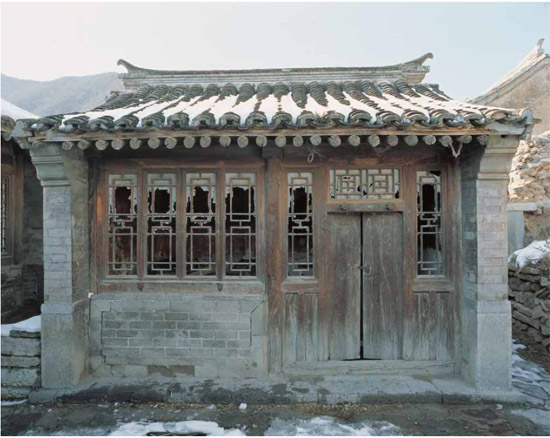

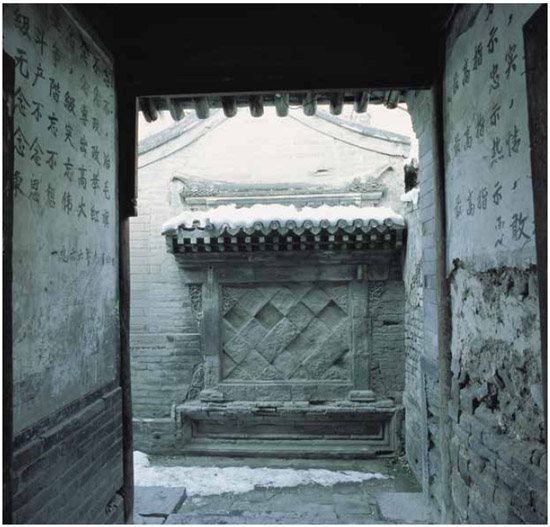

Even in the smallest courtyard structures, the conventional components of a siheyuan are apparent: a symmetrical plan, a clear hierarchical axis, enclosing walls, entry in the southeast portion of the outer wall, a spirit wall facing the gate, a rear-facing hall, a pair of side halls, and a south-facing main structure. Space in the main building is typically divided into three jian or bays although side halls often only have two bays.

In most small houses in north China, kang, heated brick beds, are connected to a cooking stove to capture the heat and carry it through the heat-dissipating bed. In several of the larger dwellings in Chuandixia, where bedrooms are often some distance from the kitchen, each kang has a firebox along its side, where burning charcoal, coal, and wood are placed to provide a comfortable space to pass bitter winter days. Kang of this type differ little in structure from those connected with the kitchen since both channel heated gases through flues or ducts embedded in the walls of the brick beds, where the heat is absorbed and then radiated to warm the surface above. Kang are fitted tightly into a space confined by thick outer walls that provide a kind of insulation to conserve heat. In those bedrooms with a south-facing wall, the lattice windows lead some additional warmth into the room even on winter days.

These drawings show the firebox, interconnected flues, and ventilating chimney, all given shape to the kang by the practical use of bricks.

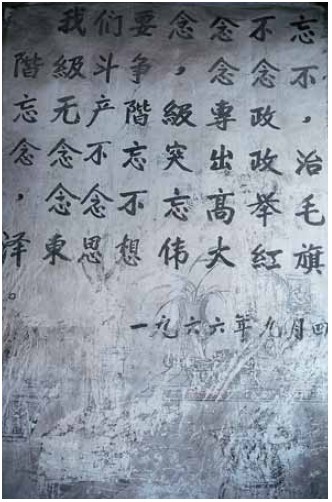

While the upper buildings in this interconnected siheyuan still await restoration, the inverted U-shaped structures below remain in good shape.

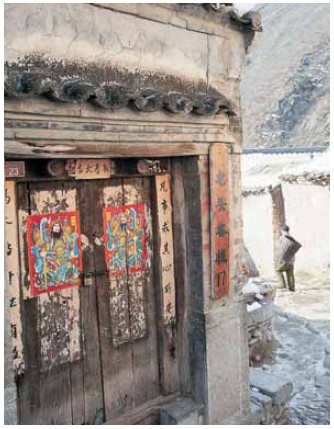

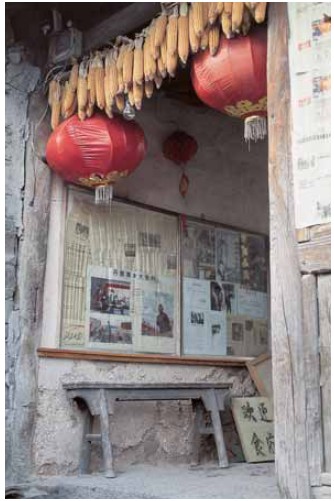

As can be seen in the many collapsing structures throughout Chuandixia, heavy column-and-beam wooden structural systems typical of north China lift the roof. Lattice window and door panels are simple in pattern and most still show the frayed evidence of the paper sheets that were once glued to them in order to block cold air. Houses still occupied disclose the colorful ornamentation and practicality of living in a country house: corn cobs hung to dry under the eaves, red paper couplets and Door Gods pasted to outer doors, newspapers and magazines glued to patch walls. While abandoned dwellings lack these elements, it is still possible to see evidence of political slogans written during the Cultural Revolution in the late 1960s, viewed today by visitors as curiosities from another era.

By the early 1990s, Chuandixia was a shell of its former self. It is said that there were about thirty households in the village in the eighteenth century that grew, according to some reports, to more than seventy households over the next century. At the end of the 1990s, researchers counted seventy-four courtyard houses in one form or another even though only eighteen households with forty people continued to reside in the village. Over time, no doubt houses were abandoned as their structures deteriorated and new ones were built nearby using easily available building materials, and thus it is not possible to establish clearly what the maximum population of Chuandixia ever was. Old residents recall that Japanese troops in 1942 burned a third of the residences in the village, perhaps actually representing only those that were occupied. Many of these scorched structures were subsequently left in a derelict state and remain so today.

It is said that attention was first brought to the village through the efforts of two painters, Wu Guangzhong in 1986 and Peng Shiqiang in 1992, who both were enthralled by the unity of the physical and cultural landscapes. In 1996, a television film used the village as a backdrop for scenes related to the 1900 journey of the Empress Dowager Ci Xi, who probably passed through the valley on her way to Xi’an via Shanxi province. At the same time, an entrepreneur named Han Mengliang, a descendant of those who settled in Chuandixia, began to think of ways of transforming a poor mountain village into a site supported by tourists. Via interviews in the Beijing press, invitations to television cameramen to visit, and a short typescript about the village, he single-handedly promoted the village. In 1998, the village was declared an “Historic Heritage Protection Zone” by district authorities, a status that was ratified in 2001 by Beijing’s municipal authorities, with a full-scale preservation plan developed. Accessible today by a two-lane highway in less than three hours, the natural landscape of Mentougou attracts Beijingers as a place to escape the confines of the city. Most come to fish, hike, ice skate, and swim, either in the wild or at sites developed to meet the needs of weekend visitors, but some have discovered the traces of old China that litter the valleys. Although Chuandixia no longer is a quiet village punctuated with the visits of imperial couriers, it still retains the physical elements of a mountain settlement of earlier times. Work will no doubt continue to refurbish the ruins of centuries of decline but little can be done to restore a sense of the difficult, yet perhaps even satisfying, life of times past.

With tattered paper on its lattice windows, this side hall shows evidence of relatively recent use, even as now it stands unused.

Fading New Year couplets and still-bright Door Gods adorn the entry of this small courtyard dwelling.

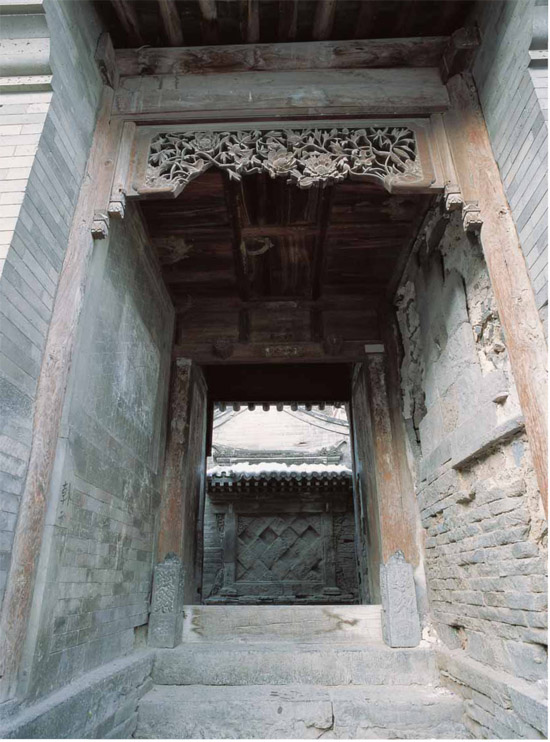

The oblong entryway of an old siheyuan reveals the abundant use of fired brick, thick wooden columns, and carved ornamentation.

Looking through the entry-way of a partially restored siheyuan, with glimpses of Cultural Revolution graffiti on opposing walls and an old carved brick spirit wall inside.

Written in 1966 during the Cultural Revolution, these phrases call for “keeping in mind the dictatorship of the Proletariat, stressing politics, and holding high the thoughts of Mao Zedong ….”

Oblique view into the entry-way of an occupied siheyuan, showing walls papered with newspapers, corn hung to dry, and lanterns to be lit at night.