Throughout the tawny-colored loessial uplands that stretch through the provinces of Shanxi and Henan in north China to Shaanxi and Gansu in northwestern China, below-ground caves, sometimes called subterranean dwellings or earth-sheltered housing, provide homes for some forty million Chinese. Cave dwellings are found in adjacent areas of Hebei, Qinghai, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and as far away as Xinjiang. Called yaodong or simply yao, meaning recessed cavities or holes in the loessial earth, this type of “building” sometimes also describes structures of stone, brick, or tamped earth built at grade level— above ground—that mimic underground forms in terms of appearance and basic character. Exquisite examples of these were shown in earlier sections.

Loessial soil, or simply loess and known in Chinese as “yellow earth,” is finely textured wind-blown silt, which has been transported by strong and steady northwestern winds from the Gobi Desert and Mongolian uplands over thousands of years into the topographically rugged and semi-arid middle reaches of the Huang He or Yellow River. Here the loess has blanketed the region with soil depths between 50 and 200 meters. Loess possesses physical and chemical properties that have made it an optimal building medium in an environment with only limited possibilities. While the soil is rather dense, it is also quite soft, generally uniform in composition, and free of stones so that it can be cut into easily with simple tools. A cement-like crust some 20 centimeters thick forms on excavated surfaces as the surface soil dries out. A region of strong annual temperature changes, with summer temperatures often exceeding 35° C while those of winter drop below 0° C, the area is also quite dry. Once covered with grasses and dense forests and a productive cradle of Chinese agrarian civilization, virtually all of the loessial uplands have been dry and denuded for at least two millennia because of climatic change and deforestation due to accelerating firewood collection, charcoal-making, land reclamation, and brick-making.

As the availability of timber declined and without the economic wherewithal to bring in building materials from outside the region, Chinese peasants for centuries came to dig into the soil to make their underground abodes just as prehistoric peoples with much less technology had done earlier. Subterranean dwellings seen today, however, are hardly primitive caves. They have evolved in structure and plan to represent a significant dwelling type that is remarkably cool in summer and warm in winter because of the conservation of heat by the thick and solid earth “roof” above and the surrounding “walls.” The use of the term “cave” is not meant to be disparaging but simply to express the product of hollowing out space inside the earth. While caves are “dwellings,” they are not “houses” even though most are “homes.” The structure of cave dwellings differs from other Chinese dwellings in that there is no three-dimensional external form built to create internal space. Rather, subterranean “structures” acquire identity from their internal form instead of their external design. Internal volumetric space, in effect, precedes structure, although there clearly is a complementary relationship between these building elements. Space is actually created without consuming the materials needed to fashion it. Excavated soils then can be used for other building purposes, such as leveling the site or for raising tamped earthen walls around a courtyard.

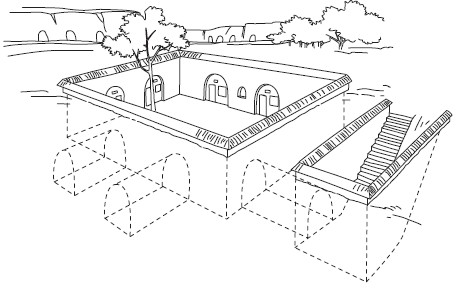

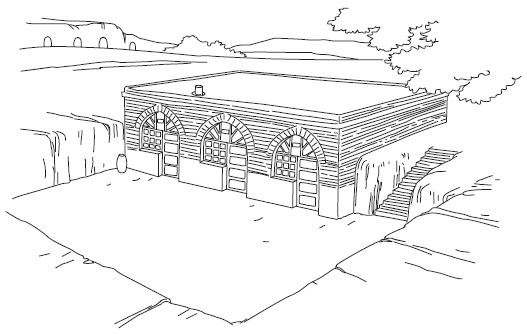

The sloping entryway and the extent of excavated side rooms are clearly shown in this perspective drawing.

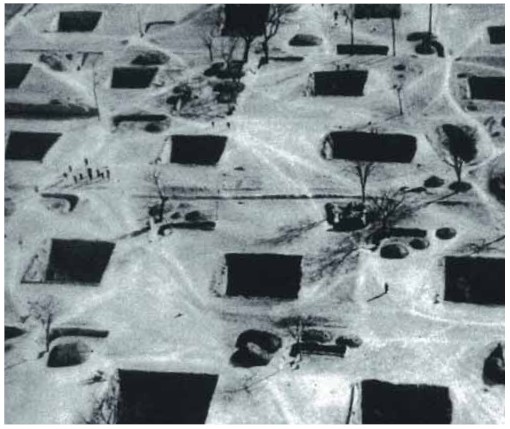

A village of sunken courtyard yaodong in Henan province presents a pockmarked landscape of geometrical indentations, each the home of a rural family.

In southern Shanxi, villages sometimes include both above-ground and below-ground dwellings.

Newly dug cliffside-type cave dwellings in southern Shanxi, dug horizontally into the slopes of elongated ravines, are here faced with brick surfaces that have been painted white.

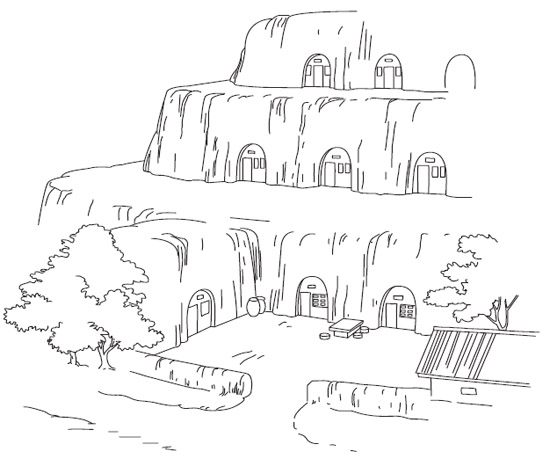

Using the irregular topography of a narrow valley, this village includes cliffside cave dwellings at many levels, which are then connected via earthen ramps.

Site selection is the most critical decision made by those constructing a yaodong. Topographic conditions, surface and underground drainage, the specific chemical and structural nature of the local soil, in addition to the seasonal passage of the sun and the impact of other natural elements on the dwelling site, all must also be carefully considered. These factors collectively contribute to decisions made concerning the ratios of height, width, and depth as well as the nature of the structural arch and enclosing façade.

Three general types of yaodong can be differentiated: cliffside yaodong, sunken courtyard yaodong, and surface yaodong. Sometimes these types are mixed and sometimes they are combined with common above-ground buildings. Cliffside-type cave dwellings (kaoya shi yaodong or kaoshan shi yaodong) are dug horizontally into the slopes of elongated ravines and usually follow the irregularity of the topography. Jagged lines of cliffside dwellings usually are found cut into south faces of slopes so that each dwelling will benefit from the light and heat brought by the winter sun, a seasonal condition favored in the construction of above-ground dwellings elsewhere in northern China. If a slope face is high and stable, it is possible to place a number of stepped or terraced levels of cliffside structures staggered one above the other. Owners of a yaodong must remain vigilant to slumping of the soil due to gravity or erosion by rain since, if the yaodong is not maintained properly, its natural structural qualities weaken and it may have to be abandoned before it collapses.

Cave dwellings usually have an elliptical shape to the façade, although semicircular, parabolic, flat, and even pointed configurations also are seen widely. Side walls are vertical for perhaps two meters before arching upwards to form a ceiling. Excavated walls of yaodong that are to be inhabited are normally coated with a plaster of loess or loess and lime to slow the drying and flaking of the interior. Papering the walls with newspapers, colorful posters, and photographs is a relatively recent innovation that at once brightens the living area and also protects the walls from absorbing condensed moisture. Usually the floor of subterranean dwellings is simply earth that has been compacted to a brick-like quality. While supplementary support of the interior walls/roof is uncommon, the façade normally is strengthened with adobe, fired bricks, or tamped earth to support door and window frames that are hewn or hand-planed. Some are wide at the opening and then narrow as depth increases while others have a constricted entry but a flared interior. Broad openings certainly facilitate the entry of both light and air, but there is a trade off in a substantial loss of heat during the winter. Where protection from cold winds is the critical factor that must be addressed, a narrow entry will sometimes be created even at the expense of diminishing natural lighting and ventilation to less than optimal levels. While the height of the longitudinal section of most cliffside dwellings is uniform, some are higher in front and lower in the rear. Cave “rooms” generally do not exceed a depth of 10 meters into a hillside, although some do reach 20 meters.

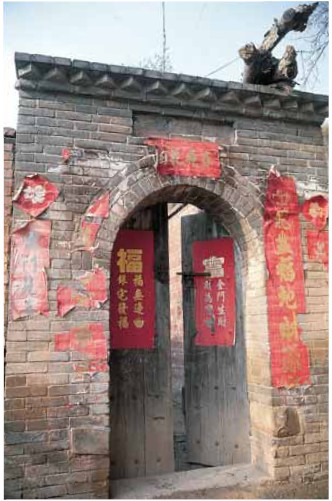

Showing the tattered remnants of calligraphic couplets pasted at the New Year, this entryway leads to a brick-walled courtyard at the front of a cliffside-type dwelling in northern Henan.

Brickwork and wooden doors mark the entrance to one recessed room of this cliffside dwelling in northern Henan.

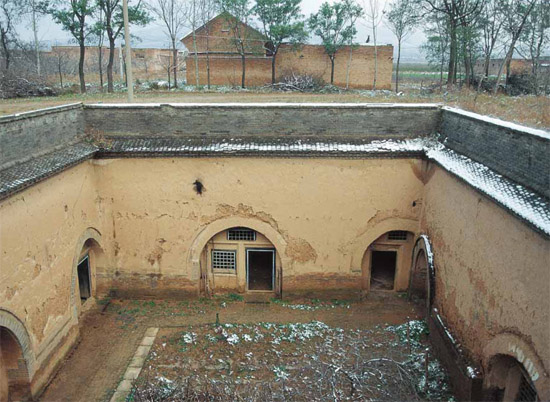

Viewed from above, the severe erosion of the soil walls of this sunken courtyard dwelling in northern Henan is apparent.

Excavating a cave is normally a slow process. This is not only because farmers do the work themselves but also because prolonging the pace provides time for the slow drying out of the soil, a condition necessary to maintain its stability. The best time for excavation is when the soil is moderately moist but not wet, perhaps several weeks after a rain. Only common farm tools such as mattocks, crude shovels, and baskets are used. Burrowing normally begins from above, at the location of the arched ceiling, and proceeds down to floor level. Excavation often begins a meter or so above grade level in order for the soil that is removed to be placed outside to form a level terrace at the entry of the cave or for some of the soil to be formed into adobe bricks or pounded into a frame in order to build a wall. A cave approximately six meters deep, three meters high, and three meters wide takes roughly forty days to excavate, with an additional three or so months necessary for the cave to cure or dry out completely before occupancy. With proper maintenance, subterranean dwellings dug into earth can be used for several generations but when neglected typically begin to break down through settling and eventual collapse. Individual yaodong chambers are sometimes interlinked to form a dwelling with many rooms, including sitting rooms, bedrooms, kitchens, stables, and storage areas—all separated from neighboring cave dwellings by walls around a courtyard, which contain a kitchen garden as well as a summer stove, pigpen, and small storage buildings.

Sunken courtyard-style subterranean dwellings (xiachen shi yaodong, aoting yaodong or dixia tianjingyuan yaodong) are found principally in the mesa-like loessial plateau in western Henan, southern Shanxi, and nearby portions of Shaanxi province. Here, peasants traditionally excavated large pits of varying sizes to depths of at least six meters below grade. When viewed from the air, the bleak landscape appears pockmarked, a condition accentuated by the shadows of the winter sun. Square sunken courtyard shapes, sometimes reaching 81 square meters in size, are most common, but there also are rectangular and L-shaped ones.

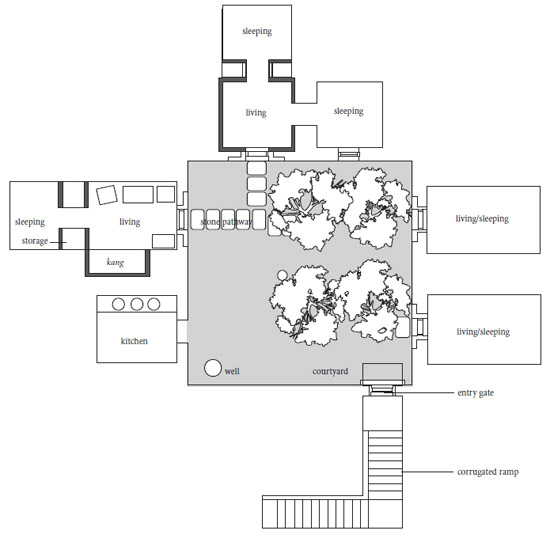

In plan view, a sunken courtyard dwelling reveals a north–south orientation as well as side-to-side symmetry.

Partially built above ground, this three-bay brick dwelling mimics cave structures in appearance and form.

The section and perspective views reveal that each pit forms a recessed courtyard whose four perpendicular side walls provide flat surfaces into which one, two, or three yaodong are dug. Entry from grade level is via a ramp or stairs sliced into the soil either along the southern or southwest sides of a sunken courtyard. Inclined passageways either run along a straight line or include right angle turns in order to lessen the gradient of the slope because of the need to move farm equipment, draft animals, and harvested crops to be stored. Oriented to the cardinal directions, cave chambers are normally dug into all four walls, which are left natural or are finished with a plastered lime surface. Chambers along the southern, north-facing wall are normally used only for storage and as a privy related to the nearby presence of stabled animals.

This couple stands in front of the main room of their sunken courtyard dwelling in northern Henan. Apparent also is a summer stove outside the kitchen that complements one inside used during the winter.

Viewed from inside, the exterior window only admits a small amount of light into the cave.

Since only one sunken wall surface can provide a southern exposure, this face usually becomes the location of the main chambers of the dwelling with bed and sitting rooms for parents and grandparents. Only during the early summer when sun angles are highest, however, does direct sunlight reach into this face. In winter, when the sun is low above the horizon and the daylight period short, the depth of the courtyard effectively shades all of the excavated space except for portions of the south-facing wall, a decided disadvantage. Living space for other family members is dug as needed into the east and west side walls. Large kang that serve as bed and sitting areas are common features of yaodong throughout northern China. Usually located along an outer wall, kang are built in so as to be connected to at least two of the walls as well as associated stoves. Shallow alcoves and lateral indentations for storage are dug into the receding sides of caves with newspapers and posters affixed to the walls to reduce flaking.

With all of these elements, the sunken courtyard becomes a “walled” courtyard compound with a significant outdoor living space open to the sky that is reminiscent of traditional northern courtyard houses. While the limited amounts of rain or snow that fall in these semiarid areas are not a major problem, blowing dust and dirt present some difficulties. As a result, low parapets of stone, brick, or tile are frequently laid along the upper edge of the excavated opening of better dwellings in order to impede the dropping or blowing of earth into the courtyard. Within the sunken courtyard itself, it is common to find a tree or two, a trellis to support vegetable vines, a shallow well, a drywell-type drain, as well as a covered cistern in which to store water. Cooking during summer, when there is no need to warm the kang or introduce heat into the cool interior, takes place outside using portable clay braziers. In winter, however, stoves, burning wood or plant stalks, maintain warmth inside and are connected to the kang.

A village of sunken courtyard-style cave dwellings presents a landscape of large indentations that is generally quite orderly. Nearby level land a bove the village dwellings is actually tilled and planted. Special attention must be paid to keeping vegetation away from the upper lip of a sunken courtyard in order to reduce the penetration of roots into the ground beneath that might draw moisture deep into the ground and lead to a deterioration of the stability of the perpendicular walls. The surface areas between the sunken courtyards of a village provide abundant expanses to meet seasonal agricultural needs such as threshing grain and storing hay.

Some yaodong are semi-subterranean with only a portion of the dwelling actually embedded within the earth. In these cases, stone, adobe, or fired brick is used to construct a building that fronts the excavated chambers, becoming in effect an extended interior part of the underground space. How such structures are added depends principally on the angle of the hill slope, resulting in all or part of each of three sides and the roof being cut into the earth.

Cave-like structures that are freestanding rather than partially or completely excavated below ground, can be seen throughout the loessial region. Aboveground cave-like dwellings, called guyao or “aligned yao,” imitate subterranean dwellings not only in terms of the appearance of their façades but also in their overall dimensions and in the use of vaulted arches that carry the weight of a substantial over-burden of earth. They are usually rectangular in shape and comprise at least three adjacent arch-shaped units, the vaults of which are created using either stone, fired brick, or adobe brick as voussoirs placed continuously in semicircular or pointed sections. Chinese architects refer to this unique building form as “earth-sheltered architecture” (yantu jianzhu or futu jianzhu) in recognition of the thick layer of insulating earth used to cap them. The surrounding walls of guyao appear to differ little from common load-bearing walls seen throughout China that support the roof. With guyao, however, the massive outer walls enclose interior space but do not directly support roof timbers and a roof surface. Instead, the side walls serve as piers that help contain the lateral thrust of the interior arches as well as bear the substantial volumes of earth that are piled in the voids above the vaulted structures and that therefore themselves constitute an insulating roof and side wall mass.

Large numbers of exquisite cave-like dwellings and even guyao are found in the cities, towns, and villages of Henan, Shanxi, and Shaanxi provinces. Serving as a deliberate choice even for upper-class dwellings, they comprise simple courtyard complexes as well as extensive manors or estates. Several complexes of below-ground and above-ground dwellings have been discussed in earlier sections. Above-ground cave-like guyao preserve the positive attributes of yaodong while eliminating some of their negative aspects. In terms of their thermal performance, the substantial earth, stone, and brick walls on three sides and on the roof as well as the earth beneath provide excellent insulation from severe cold in winter and intense heat in summer. Air circulation is typically better within dwellings adjacent to courtyards above ground than in those built into the earth below ground. In some manors of the rich, there is the ambience and intimacy of a rural village of cave dwellings, which is enhanced by expensive ornamental treatment of wood, stone, and brick that is not usually found in the often poor villages of the loessial plateau.

Cave dwellings represent a positive adaptation to environmental conditions in that they creatively utilize an abundantly available resource—soil—by effectively capitalizing on the thermal qualities of the earth—warm in winter and cool in summer— and by ingeniously exploiting terrain that normally would not be suitable for housing. In a semi-arid region in which wood and brush for cooking fuel are themselves strikingly scarce, the reduction in the need for wooden building materials is fortunate. When the outside temperature during July and August is above 36° C, four to six meters below ground inside cave dwellings, the temperature is a relatively comfortable 14° to 16° C. During January and February, when above-ground temperatures drop to their lowest, interior temperatures below ground are still between 14° C and 16° C depending on the location in the dwelling. Temperature ranges throughout the day are similarly rather stable, a condition that is best appreciated late at night when outside temperatures in the region typically plummet. These numbers are especially striking when compared with those inside surface dwellings in north China. Powerful earthquakes, however, have brought periodic devastation to those living in subterranean dwellings in the loessial uplands, which unfortunately lie along an active seismic belt. Between 1920 and 1934, perhaps as many as a million people died in collapsing yaodong and other dwellings in the loessial region.

In the eyes of many, yaodong —cave dwellings— are equated with poverty and limited resources. It is not surprising then, that as farmers have more cash income, more and more are abandoning their caves, sometimes even filling the indentations and leveling the earth, and building above-ground dwellings. This effort to make progress, however, is made difficult by the fact that the new houses are neither as warm in winter nor as cool in summer as the old. They are nonetheless better ventilated than nearby subterranean dwellings. Major efforts are being made by Chinese architects to address the shortcomings of yaodong —limited interior light, inadequate ventilation, and high humidity levels—in order to meet the escalating housing needs of villagers.

A sunken courtyard, not surprisingly, helps to keep in check the movements of animals, providing in effect a pen that restrains them. Here, in what serves as a veritable barnyard, pigs are allowed to range freely outside their pen in the crude cave in the rear. Nearby, although not seen, is a cow. Chickens, on the other hand, are penned in an adjacent cave with a gate fashioned of branches. Fuel wood that has been scavenged in nearby hills is stacked here and there.