The Jiangnan or “South of the Yangzi River” region is crisscrossed with countless canals and dotted with small canal-side villages and towns in addition to some of China’s richest cities. To geographers, this area, which includes placid Lake Tai and extends from Nanjing eastward to Shanghai, is remarkable for its hydrography rather than its topography, its low-lying terrain, and its traditional life centering on the omnipresent water environment. At least since Sui dynasty times when the Grand Canal was built, the name “Jiangnan” rarely is used without the addition of the adjective “prosperous.” As the land of abundance, “the countryside of fish and rice,” and the home of China’s silk industry, the water-laced Jiangnan region has long been known for its robust commercialized market-oriented economy linking villages, towns, and cities. In once-quiet cities like Hangzhou, Suzhou, Wuxi, and Yangzhou, as well as in countless settlements beyond the metropolitan centers, as both wealth and population increased a refined literati culture came to thrive and give these cities a distinctive character.

Residences with associated gardens epitomize the finest forms of domestic architecture in Jiangnan. Private literati or scholar gardens, sometimes simply called classical Chinese gardens, especially, were designed for those who expected simplicity, elegance, and poetic meaning in their daily lives. Such gardens, of course, were an integral part of a scholar’s house, to the degree that the Chinese notion of a home is explicitly included in the term yuanzhai or “garden-house.” Although some “garden-houses” are sprawling complexes that blend varieties of buildings, rockery, water, and vegetation, most resort to nature in miniature in order to array aesthetically pleasing aspects of these complementary elements into relatively small spaces. None of China’s magnificent literati garden-houses is portrayed in the sections that follow. Instead, attention is brought to a small yet graceful residence of a Ming-dynasty calligrapher, painter, poet, and dramatist in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, and a canal-side residence of a merchant in Luzhi, Jiangsu, that once must have been alive with the comings and goings of family and commercial activities.

Once there were hundreds of villages and towns tied to the Jiangnan canal network, but now only a handful still echo in layout and lifestyle the waterborne settlements of the past. In a rush to modernize and industrialize in recent decades, far too many traditional settlements were hastily sacrificed when their past forms and identity were erased with the building of new houses and factories, the filling in of canals and marshes, as well as the construction of roads. Attention to the conservation of Jiangnan watertowns, however, did begin in the 1980s under the inspired attention of Ruan Yisan of the Department of Architecture of Tongji University in Shanghai, and has led to a handful of remarkable preservation successes. In the process, some watertown settlements and buildings within them, which had been seen by some as dilapidated and dysfunctional, have undergone restorative transformations and become significant heritage sites for domestic tourists. Planning principles, well thought out before either finances or tourists climbed to the levels experienced in recent years, focused on locating new construction outside the historic districts, making repairs to old buildings, improving water quality, and burying electrical and telephone lines. In order to maintain the rhythms of daily life and for villages and towns not to become merely sets of structures to be consumed by tourists, heritage issues and livelihood issues were confronted in comprehensive ways.

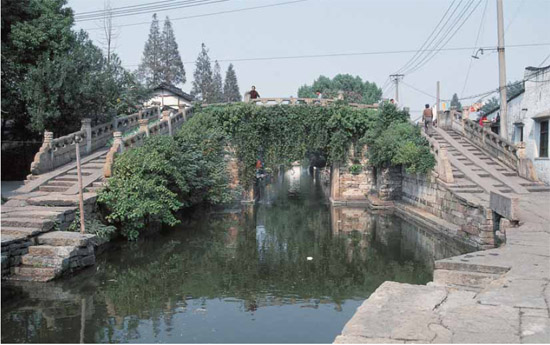

It is still possible, even as the twenty-first century begins, to experience authentic expressions of China’s past because of the distinctive, irregular layout of each watertown and the tightly packed and often odd structures along their irregular stone-paved lanes. On and adjacent to canals and ponds as well as along the lanes, traditional activities can still be seen. Waterside pavilions, quaint teahouses, temples, memorial arches, high stone bridges, most at human scale, contribute to a generally slower pace of life welcomed by visitors and residents alike.

Among the most noteworthy of extant watertowns are Wuzhen, Nanxun, and Xitang in Zhejiang province as well as Luzhi, Zhouzhuang, and Tongli in Jiangsu province, which have been put forward as a group for designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Although, sadly, many others have been developed beyond recognition as a watertown, others are in various states of preservation, especially Dongpu, Keqiao, and Anchang near Shaoxing in eastern Zhejiang, and Jinxi, Shaxi, Mudu, and Guangfu near Suzhou in southern Jiangsu. Most are within a couple hours of Shanghai, China’s mega city, and thus have already felt the impact of swelling visitation. Chinese tourists dominate tourism in China, enticed to off-the-beaten-track locations by websites, news reports, word of mouth, and increased affluence.

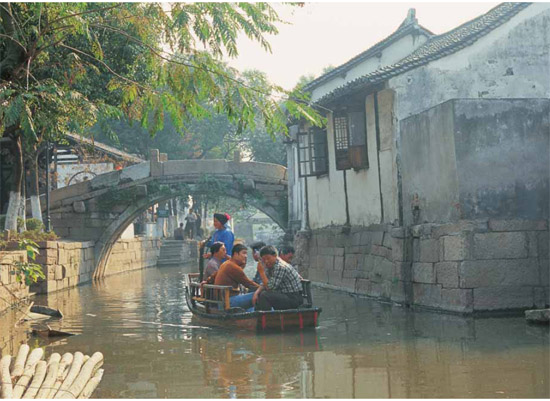

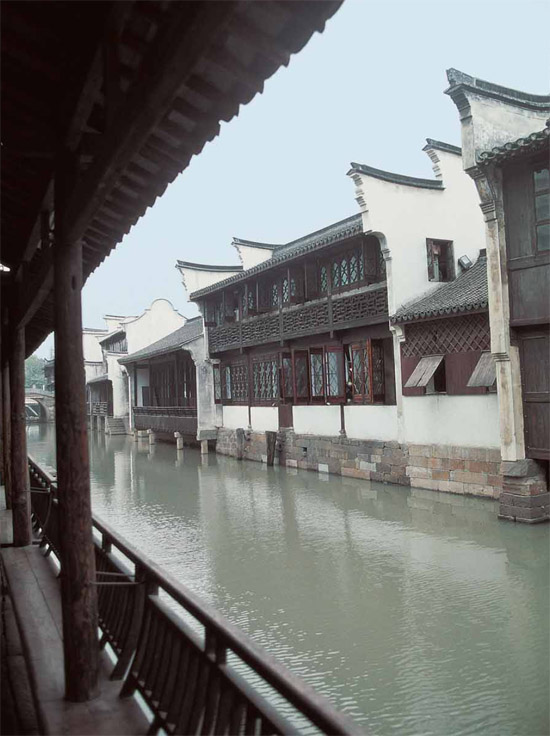

While still important in the life of local residents, canals in many towns such as Luzhi, Jiangsu, shown here, serve as routes to carry tourists as they explore local culture.

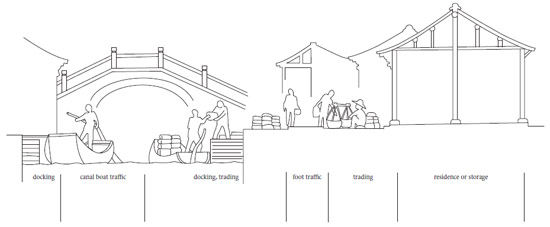

Throughout the water-laced Jiangnan regions, while differing in details, narrow canals, arched bridges, small boats, as well as water-side residences and shops provide convenient places for living and trading.

Map depicting the hydrography of the Jiangnan region and showing the most prominent canal towns.

At the junction of two canals, a teahouse in Luzhi, Jiangsu, provides a pleasant sanctuary for locals and visitors.

Luzhi, Jiangsu

Luzhi, like many Jiangnan watertowns and villages, greets the morning bathed in semi-transparent mist. Especially from late spring into early summer, the so-called meiyu or “plum rains” bring consecutive days of lachrymal drizzle at a time when plums ripen and rice is ready to be transplanted. With very little sunshine, sultry temperatures, and high relative humidity, the homophonous association of meiyu with “mold rains” becomes quite apparent to residents as shoes, bedding, and other stored items, even rice, in poorly ventilated areas easily grow moldy. Much attention during this period is focused on trying to prevent mold growth by moving items from the dark into the light, yet everyone recognizes ultimately the need for drying and airing such items in the intense sunshine that will inexorably follow the lingering “plum rains” by mid-July.

Until recently, it was easiest to reach Luzhi by small boat rather than car or bus, being sculled along narrow canals, the arteries of country life, through a relatively low landscape of paddy fields separated from each other by slightly elevated embankments. Virtually all of the original woodlands and marshes were extinguished as peasants replaced them with irrigated fields and perennial bushes and trees with important economic value, such as mulberry, tea, masson pine, and fruits. Chinese straightforwardly refer to these areas as shuixiang or “water country.” In the past, these agricultural products also always were moved by boat to small canal-side settlements, like Luzhi, where they could be processed, stored, and marketed. Stone pathways and countless stone and wood bridges facilitate foot traffic.

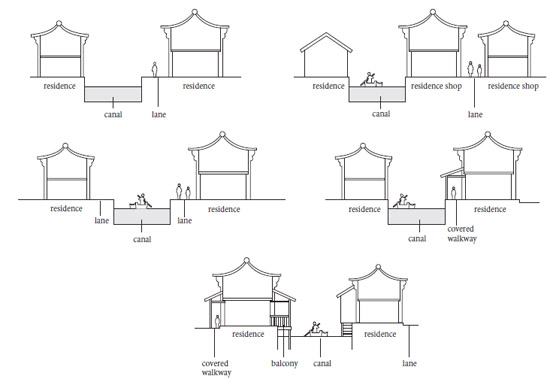

With an area of only a single square kilometer, Luzhi is said to have once had seventy-two bridges, although only forty remain, a fact that places a convenient bridge every hundred or so paces. Hefeng Bridge, an arch-shaped structure said to be the oldest, was built of granite during the Song dynasty, but most bridges date from the Qing dynasty. Just beyond Xinglong Bridge in the eastern part of town is the Wansheng “Extremely Prosperous” Rice Company, an expansive courtyard complex built in 1910 as the center of business for a pair of entrepreneurs who had a network of a hundred warehouses for storing and milling rice in the region around Luzhi.

With lattice windows thrown open in early morning, this second-floor teahouse in Luzhi, Jiangsu, has been readied for visits by residents and tourists.

Outdoor stages for the performance of local opera are common in towns and villages throughout southern China, such as this one in Zhouzhuang, Jiangsu.

The two best-preserved houses in Luzhi are those of the Xiao and Shen families. Located on a lane in the northern part of Luzhi, what is now called the Xiao residence was actually built by a man named Yang in 1889. Sold early in the twentieth century to Xiao Bingli, who was a partner in an electric bulb manufacturing venture, the house today stands as a museum celebrating the 1960s Hong Kong movie superstar Siao Fong Fong, also called Josephine Siao, Xiao Fangfang, and Hsiao Fang Fang. Although the legendary screen actress never lived in the house, having been born in Shanghai in 1947 and moved to Hong Kong as a young child, she is the granddaughter of the Luzhi Xiao family. As a well-known Hong Kong television personality, philanthropist, and mature film actress, her fame brings countless visitors to the Luzhi Xiao residence to see the exhibits spread throughout the nearly 1000-square-meter residence, a good example of a late Qing-dynasty nouveau riche. The much larger nineteenth-century Shen residence, the home of an educator and merchant, is discussed in the next section.

Zhouzhuang, Jiangsu

With a history of some 900 years, Zhouzhuang watertown occupies a slightly elevated level expanse in a township that has some 24 percent of its area covered by water. Its somewhat isolated physical location amidst the “water country” helped preserve it as a relative oasis within the corridor zone between Shanghai and Suzhou, which underwent extraordinary development from the late 1980s onward. In 1986, Zhouzhuang was cited as a “last frontier” settlement worthy of preservation. Even as some remarked about its backwardness, decay, and sleepy nature, others began to plan for its conservation.

Set in a landscape dominated by water, Zhouzhuang town is shown in this nineteenth-century map as being made up of a series of islands connected by strategically located bridges.

Stone bridges throughout the Jiangnan water region rise high above the canals beneath, providing steps for pedestrians and those carrying goods. Shops and tea-houses cluster around both ends of the Fu’an Bridge in Zhouzhuang.

Throughout the Jiangnan region, lanes, canals, and buildings are aligned in a variety of patterns.

Here, early in the morning, well before activity disperses them throughout the town, small boats are moored in such numbers that they clog the canal.

Among the best-known bridges in China is the Bazi Bridge, which is said to have been built in 1256 during the Song dynasty. With its gentle approaches and a principal span that clears 4.5 meters, the bridge fits compactly into a tight residential area. The bridge is one of some 400 found in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, called by some “China’s Venice.”

Records trace the origins of the village back to a landlord named Zhou Di, who established a settlement here in 1086 during the Northern Song dynasty. However, it was in the several centuries after 1127, after the Southern Song dynasty had moved to Hangzhou in adjacent Zhejiang province, that Zhouzhuang grew and flourished. By the seventeenth century, the population of Zhouzhuang had grown to 3000, peaking perhaps at 4000 in 1953. However, by 1986 it had declined to only 1838. Over the past fifty years or so, the steady decline in the population and the effective abandonment of old buildings once alive with residents forestalled the destruction of many old structures.

Concentrated within a half square kilometer of Zhouzhuang are some 60 percent of the watertown’s Ming- and Qing-dynasty structures, arrayed along a mesh of waterways that are the backbone of the old town. The principal canals are somewhat irregular in alignment yet together at the core of Zhouzhuang approximate the Chinese character meaning “well.” Complementing these are narrow lanes and alleyways that largely parallel the canals, with a multiplicity of juxtapositions. Canals divide the town into islets that are connected by nineteen bridges, each of which serves to link and is a hub of activity.

Tourism in Zhouzhuang began in the early 1990s, well before that of other watertowns. By then, some of the egregious damage of recent decades had been ameliorated. One spacious old residence with seventy rooms called Yu Yan Tang or “Hall of Jade Swallow,” initially built for the Xu family in the fifteenth century during the Ming dynasty before being sold to the Zhang family during the early Qing dynasty, was finally emptied of the seventeen families who had come to occupy it after 1949. The Shen Benren residence, built in 1742 and covering an area of some 2000 square meters, including seven courtyards and approximately 100 rooms in its plan, was used as a machine-making factory up until the late 1980s. Today, it has pride of place as a restored structure representing the glory of Zhouzhuang in the past.

Wuzhen, Zhejiang

Situated along the Grand Canal in northeastern Zhejiang, Wuzhen is threaded with narrow canals, which are crossed by numerous old stone bridges. Only open to visitors since 2001, Wuzhen is one of a handful of beautiful canal-side towns that straddle the watery border between Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. Unlike some of the better known watertowns, little of Wuzhen has been restored, yet many old buildings remain in a noteworthy state of preservation. Life in Wuzhen is much as it was in the past, with remarkably few buildings specifically serving tourists. Walking along any of the narrow lanes, one can easily glimpse the rhythms of daily life: people carting fresh water, cooking meals, tending to young children, and playing mahjong. Local workshops continue to make wine and homespun cotton, in addition to items made of wood, silk, and metal.

Viewed from a covered arcade along a canal in Wuzhen, Zhejiang, the backsides of shops and residences on the other side enjoy canal-side views. Some even have steps that allow access to the water.“Horses’ head” stepped gables with gray tiles atop them rise above the whitewashed walls of houses throughout the town.

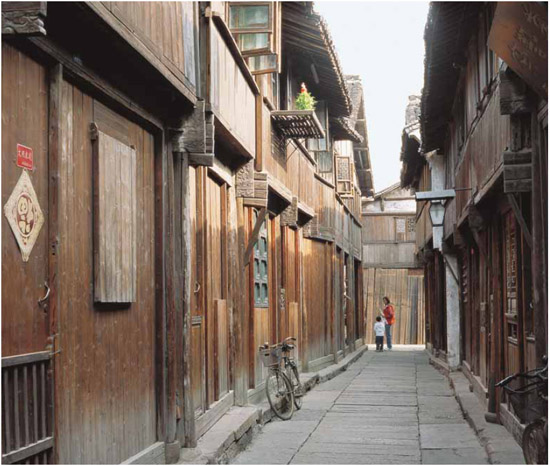

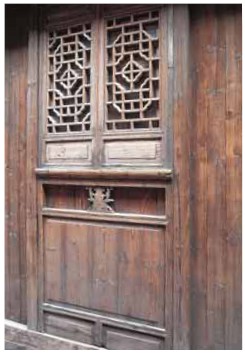

Two-story wooden buildings, usually with a shop on the ground floor and living space above, line narrow lanes in many canal towns, such as Wuzhen, Zhejiang. While the lower floor can be shuttered with wooden planks, the upper story remains airy because of its large lattice windows.

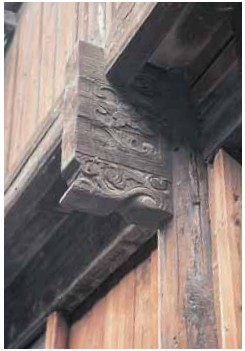

Carved bracket used to support the slightly overhanging upper floor.

Decorative ornamentation of a wooden door and window panel.

Lu Xun (1881–1936), one of China’s outstanding modern writers, spent the first third of his life in a canal-side residence in Shaoxing, Zhejiang. With large brick flooring, white walls, moon-shaped openings, and lattice windows, spaces are quite bright and cool during the day.

Many houses have their fronts along a lane and their backs against the water, thus function as shops or workshops and residences. With striking brick walls painted white and capped with stepped gables, which create intermittent firewalls, the structures themselves are usually constructed of wood, two stories tall, with a higher ground floor and a shallower loft. Ornamentation is rarely ostentatious, generally nothing more than carved wood brackets and supports. The patina of unpainted aged wood complements well the other natural surfaces of cut gray granite foundations, dark roof tiles, and mottled whitewashed stepped gable walls. Many of the shop-dwelling structures are raised on piers over the adjacent canal and have steps leading down to a stone landing where a boat can be tied or laundry washed.

The historic area of Wuzhen, 1.3 square kilometers in size, is entered through a recently restored soaring pailou or ceremonial archway leading to a high stage for Chinese opera performances. In this area, a number of structures have already been restored to their late nineteenth-century condition, including the birthplace of the writer Mao Dun, a Xiuzhen Daoist temple, a pawnshop, and a traditional pharmacy. Adjacent portions designated as part of the historic area are being developed with an emphasis on improving infrastructure, including placing water pipes and electric wires underground, repairing old walkways, removing newer structures, and assisting long-time residents to move to new housing. One prominently restored area is called “workshop area” with shops producing and selling rice wine, dried red tobacco, cotton dyeing, cotton shoes, as well as rattan, bamboo, and wood products.

The writer Lu Xun, who was born in Shaoxing, studied the classics in a private school, depicted here, called the Sanwei shuwu (Three Tastes Studio, the three “tastes” being history, poetry, and philosophy).

Shaoxing, Zhejiang

Located just to the south of Hangzhou Bay within a “water country” similar to that north of the bay, Shaoxing has a longer and more glorious history than most Jiangnan watertowns. Some 2000 years ago, Shaoxing, which was then known as Guiji, was the capital of the Yue kingdom during the Spring and Autumn period, and it is said that Yu the Great, a legendary emperor, learned to control floods in the environs of Shaoxing some 5000 years even before that time. Yu the Great’s mausoleum located nearby remains a special place of veneration. Shaoxing today is a modern city of nearly 350,000 people surrounded by economic development zones. Even if most of the traces of its earlier existence as a watertown are long gone, the city still retains sites of historic significance, including scores of homes of illustrious residents such as Xu Wei, Ming-dynasty calligrapher, painter, poet, and dramatist, and Lu Xun, progressive twentieth-century author. None of the watertowns near Shaoxing, such as Anchang, Dongpu, and Keqiao, has received the kind of attention or investment in preservation seen in other Jiangnan watertowns to the north and thus all have had their historical cores impinged upon by modern industrial development. Still, each has a number of slow-moving canals with busy boat traffic and vestiges of traditional commerce mixed with that which is modern. Coopers, stone carvers, quilt makers, bamboo craftsmen, and metal smiths occupy many workshops-cum-residences along the canals.

In each watertown, the daily life of the inhabitants continues even as the modern world intrudes. On the main streets, new cars and buses increase even as pedestrians and bicycles continue to dominate the back alleys. Along the granite-paved lanes lined with one- and two-story wooden shophouses, men, women, and children do as they have always done: shop for fresh produce, chat with neighbors, cart water, cook meals, clean out buckets, and tend flower pots. Numerous artisans work in many old workshops, producing as they have traditionally done objects made of copper, wood, cotton, silk, and paper. In order to protect an area of somewhat dilapidated traditional canal-side housing and shops, the Cangqiao lane area was rehabilitated in 2001 in an effort to improve the quality of life for residents while preserving aspects of Shaoxing’s architectural heritage. Each of the old watertowns has a nearby “new town” with multistoried apartment blocks, schools, factories, and shopping centers, judged by most residents as more comfortable and convenient than the tightly packed old town.