Today, it is difficult to appreciate the fact that northern Henan province was once a center of gravity for imperial China, that Luoyang and Kaifeng were important dynastic capitals, and that agriculture and trade brought riches to many families in what the Chinese call Zhongyuan, the fertile Central Plains. Straddling the now rather desolate Yellow River or Huang He, this region once thrived because of a trade network linked to the river system as well as to an old system of roads. Subsequently, the shifting of imperial capitals to the south at Hangzhou and Nanjing and then during the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties to the north at today’s Beijing, as well as out-migration of population, brought about the region’s relative eclipse as wealth and power moved elsewhere. Today, the region is best known for its railroads, factories, and cotton production, as well as a scattering of prehistoric sites, the Buddhist sculpture at the Longmen Grottoes, Han- and Song-dynasty imperial tombs, and some of the country’s oldest Buddhist and Daoist temples that draw visitors to the region. Few are aware that here are vestiges of life lived in the past by some of China’s great families in their great estates.

Midway between Luoyang and Kaifeng and to the south of the Yellow River in Gongxian, today called Gongyi, is Kangbaiwan zhuangyuan, the Kang family manor. From the late Ming dynasty into the early part of the twentieth century, the Kang family triumphed over the well-known Chinese proverb, “Wealth does not last for more than three generations” (fu buguo sandai), by maintaining relative unity for about twelve generations over a period of about 400 years. With little formal division of their family organization or dissipation of family wealth, their productive agriculture and trading empire allowed them to build up a complex estate centered on Gongxian. At its peak, the relatively self-sufficient estate included not only a walled compound for the immediate family and nearby residences for other kin as well as retainers, but also ancestral worship facilities, workshop areas, inns for travelers, stables for riding, pack, and work animals, livestock pens, a brick and tile-making kiln, a military camp, and a granary and stores complex. While only the traces of most of the ancillary structures exist, what does remain of their vast domain is China’s largest walled complex of cliffside subterranean dwellings called yaodong, simulated subterranean structures called guyao, and aboveground buildings, all composed around a series of interlinked courtyards. The Kang manor dominates Kangdian village, a community of farmers, many of whom still live in subterranean dwellings, traditional cave dwellings, in the numerous gullies associated with the heavily dissected plateau behind it. It is said that the Empress Dowager Ci Xi visited here on her way back to Beijing from Xian in 1901 after the conclusion of the Boxer Uprising, and it was she, according to legend, who hailed the Kang family as baiwan, meaning “millionaires,” leading to the place itself being called Kangbaiwan—“Millionaire Kang’s.”

This pair of section views of the Kang family manor highlights the way in which the residential complex has been sculpted into a terrace along a loessial cliff. In addition to interconnected buildings arranged around courtyards, caves were dug into the cliff face to provide important spaces for family activities.

This nineteenth-century drawing not only illustrates a perspective view of the residential portion of the Kang family manor but also shows other parts of the self-sufficient estate, including workshops, inns, stables, livestock pens, a granary, kilns, and a military camp.

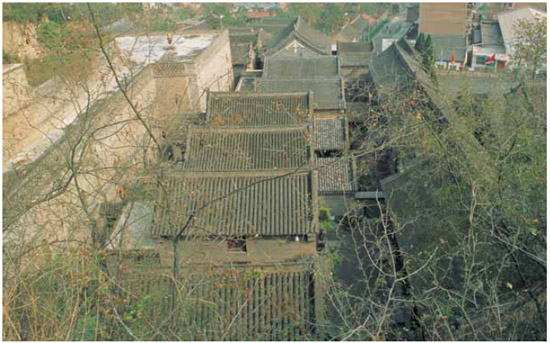

Looking towards the east from high on a nearby ridge, the parallel roofs of adjacent courtyards as well as the sculpted face of the earthen cliff are shown clearly.

At the top of the inclined passageway leading up into the manor is a carved brick spirit wall featuring the three stellar gods of Good Fortune, Emolument, and Longevity. A detailed view is shown on page 90.

The outer courtyard of the easternmost residential unit includes a heavily ornamented transitional building structure with a pair of facing side buildings.

Spread along the slopes of several loessial terraces above the Yiluo River, the Kang manor complex was begun during the late Ming period, but it was not until 1821 that the 12–15 meter-high crenellated protecting wall was built around an area that came to encompass their grand residential complex. Most construction spanned the period 1828–1909, during the waning century of the Qing dynasty, until it covered some 64,300 square meters. In order to create a sufficiently large, elevated, and level building site 83 meters from north to south and 73 meters wide, much earth was removed from the slopes and used to fill in lower elevations that were banked with massive stone and brickwork. The L-shaped cutting into the loessial soil created flat walls into which yaodong were dug into the ridge, supplemented by guyao, arcuate cave-like structures, and above-ground buildings, all fashioned around traditional, but narrow, courtyards. A 23.7-meter-long underground arched passageway, lined with bricks and secured with a strong gate, leads from below up a slope into the residential compound. At the top of this ramp is a magnificent baked brick spirit wall with carved images of the three immortals or stellar gods, representing Good Fortune (fu), Emolument (lu), and Longevity (shou), as well as other auspicious imagery.

The main residential area includes five distinct courtyards, aligned parallel to each other with separate gates leading into each courtyard, while smaller gates lead to connecting passageways that pierce the shared party walls between the courtyards. The easternmost, largest, and longest courtyard is called the “old courtyard.” Rigidly symmetrical and with a length of nearly 55 meters and width of 14.5 meters, the courtyard sequence includes a main gate, an open courtyard, and an entry structure that leads to a pair of heavily ornamented side buildings and the main structure in the rear. The surviving matriarch of the family occupied this main structure at the beginning of the twentieth century, when the Empress Dowage visited in 1901. Her longevity, having already celebrated her 100th birthday, and the fact that Kang family members of four other generations still occupied the complex, brought pride to the family in that they had attained the ideal of “five generations living under one roof.” Her apartment in the innermost structure included three rooms: a central hall, a sitting room on the east, and a bedroom on the west.

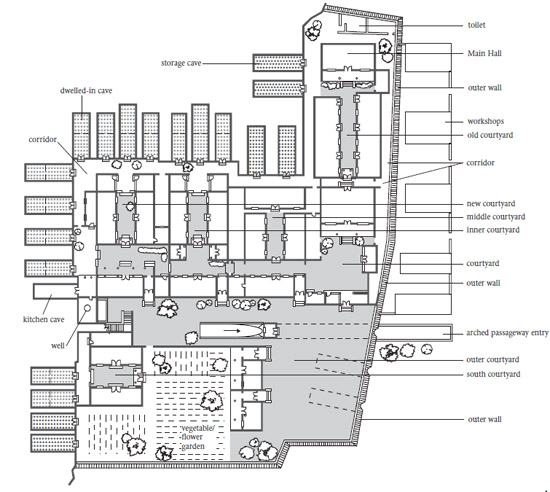

In plan view, the five aboveground multi-courtyard residences are shown as independent entities, with each connected to the others via passageways and gates. They also incorporate deep caves dug into the hillside as important residential spaces.

Shown here is the bedroom of the Kang family matriarch as it is said to have looked in 1901 when she celebrated her 100th birthday. The view is from her sitting room through her formal Main Hall into her bedroom with its large and elaborate canopy bed.

Carved on the frame of a bedstead are images of the three Stellar Gods.

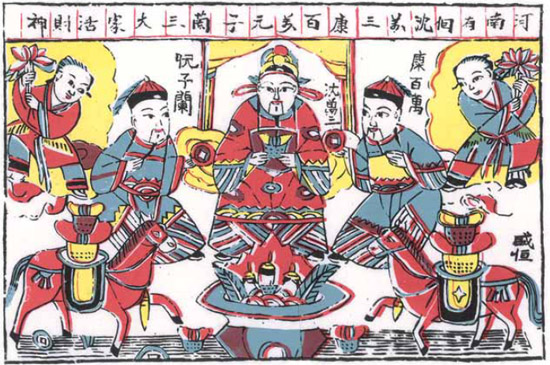

This polychrome woodblock print depicts “The Three Living Gods of Wealth,” including Kang Baiwan, the lord of the Kang family, who achieved the status of folk god and was said to be worshipped by villagers throughout north China.

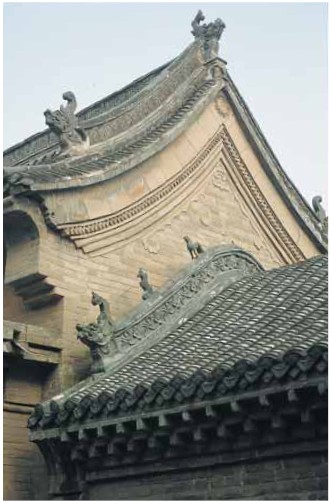

The four other courtyards are less grand than the first one, with each nonetheless having some distinctive feature, and all including underground cave structures as component parts. All of the buildings are made of gray brick with the type of flush gables common on palace architecture in Beijing. Steps, corridors, and gates of many types served as markers of interaction, at once linking as well as separating spatial activities from courtyard to courtyard.

One courtyard has facing side structures set up to show the different spheres of males and females, with martial arts and learning emphasized for boys while domestic talents, like weaving, embroidery, and sewing the focus for girls. In a rear cave is a shrine for “Three Living Gods of Wealth,” including Kang Baiwan, folk gods said to be worshipped by villagers throughout north China. The entry to the middle courtyard has a strikingly gnarled tree as well as a horizontal board proclaiming “Capable of Prudence in Following the Way.” In the rear corner is a cave divided into two parts, the front section serving as a school for young children and the rear as a pharmacy. Both were the responsibility of the family tutor, who used the Sanzi jing, the “Three-Character Classic,” as a principal text for rote learning and inculcating children with moral tales. Children sat around the low table to recite from texts and memory as well as to practice calligraphy. Two lines in the Sanzi jing express clearly the expectation that teachers were to be strict: “To teach without severity is a fault in the teacher.”

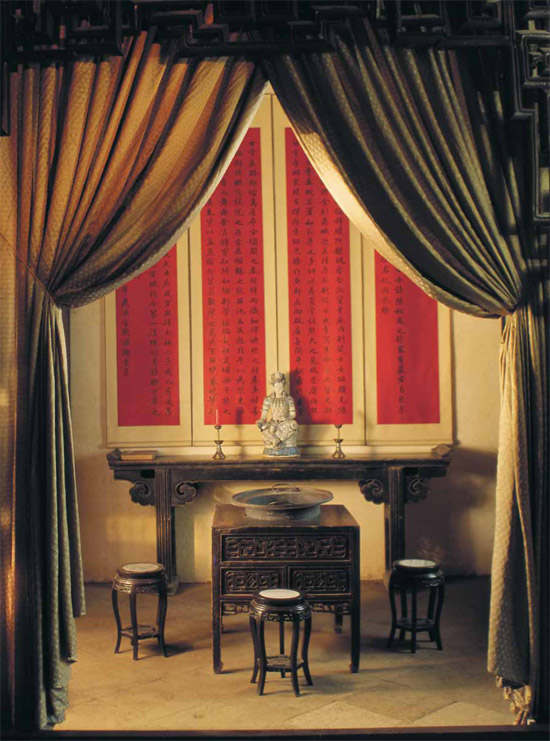

Opposite the matriarch’s bedroom and framed by heavy drapes is a sitting room in which to entertain guests.

In the apartment of a young woman of the Kang family, the highly stylized Main Hall is decorated in the style of the late Qing dynasty.

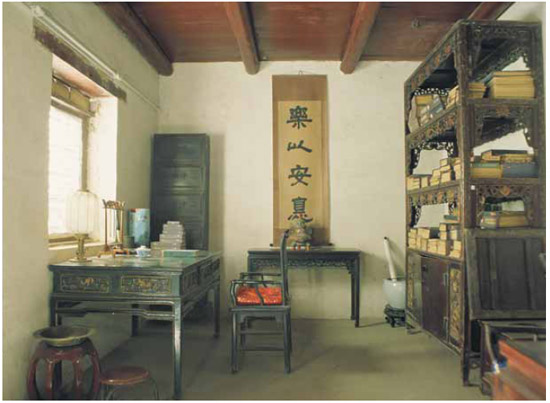

In one room of the apartment of a young man of the Kang family, books are piled on bookcases and items needed for calligraphy—ink stone, ink stick, brushes, and paper—arrayed on a desk.

By the early years of the second decade of the twentieth century, just as China itself devolved into warlordism, the Kang family’s finances declined dramatically even as their power also weakened. In time, a reputation as exploiting landlords, rather than enterprising entrepreneurs, came to characterize them. After 1949, during Land Reform, all of their land was confiscated and distributed to peasants, and some 3000 objects owned by the family were seized and locked in warehouses. In 1968, during the height of the Cultural Revolution, three “evil landlords”—Liu Wencai from near Chengdu in Sichuan, Mou Erhei from near Yantai in Shandong, and Kang Yingkui in Gongxian, Henan—became the focus of a political campaign highlighting their oppression of the masses. An unintended consequence was that each of their large estates came to be preserved as sites for mass education about the evils of landlords, rather than being destroyed like so many other fine residences. Throughout the 1990s, efforts were made to restore the complex, and in 2001 the Kang family manor was granted national protection as an historic site. The fact that old family furniture could be taken from where it had been safely stored and the residential complex had suffered only minimal destruction meant that restoration has been relatively quick and straightforward.

This richly decorated bedroom used by a young girl includes an elaborate alcove bed, a dressing table, storage cabinets, small decorative objects, and a washstand. Pride of place is given to a frame holding the daughter’s embroidery. It was on frames of this sort that a young girl would ply the needle as she prepared embroidered pillowcases, clothing, wall and bed hangings, and slippers, among many other articles that became part of her dowry.

Framed by a conspicuously gnarled tree, the entry to the middle courtyard has above it a horizontal board declaring “Capable of Prudence in Following the Way.”

Made of gray bricks, the flush gables found on each building are similar to those commonly seen on palace architecture in Beijing.