♦

At the turn of the millennium, “globalization” has become a catchword used worldwide. Increasing economic interconnectedness has led to a profound political and social revolution. Old certainties are cast into doubt. The nation-state, the decisive driving force of the past two centuries, is dissolving under the pressure of a cross-national integration, which has developed with a dynamic and a momentum of its own.

Often we believe that this process is irreversible, that it provides a one-way road to the future. But historical reflections lead to a more sober and more pessimistic assessment. There have already been highly developed and highly integrated international communities that dissolved under the pressure of unexpected events. But in every case the momentum was lost; the pendulum swung back. In Europe, for instance, the universal Erasmian world of the Renaissance was destroyed by the Reformation and its Catholic counterpart, and separatism, provincialism, and parochialism followed. A more immediate (and perhaps more familiar) precedent is the disintegration of the highly interconnected economic world of the late nineteenth century.

No collapse, of course, is precisely like any other. In the following pages I will not be attempting to argue that the Great Depression of the twentieth century will be restaged in the twenty-first. But each collapse results from patterns of thought and institutional mechanisms that arise in response to a new and unfamiliar international or cosmopolitan world. The form of such reactionary resentment remains astonishingly similar over long periods.

The failure of the World Trade Organization ministerial meeting in Seattle in November 1999 gives some indication of the problems facing the interconnected world today. The major industrial states failed to organize a realistic agenda. They overburdened the trade talks with inappropriate demands about environmental and especially labor standards, which many developing countries interpreted as a new protectionism under another guise. Finally, they appeared to encourage the apocalyptic street scenes in which citizens of mostly rich countries, who might have been expected to see themselves as beneficiaries of globalization, rioted against the new economic order. Instead of serious trade talks, Seattle turned into a chaotic symbolic protest against the internationally diffused culture of McDonald’s: the beginning of a new phase in two long-standing conflicts, the North against the South, and the rest of the world against Americanism. Both are battles in a conflict over globalism. Did the battle of Seattle set the tune for the new century?

This book explores the Seattle scenario—the circumstances in which globalism breaks down—by using a historical precedent, the collapse of globalism in the interwar depression. This collapse destroyed the financial power of the country, Great Britain, that had been the dynamic force behind the internationalization of the economy in the nineteenth century. It prompted, especially in Nazi Germany and imperial Japan, innovative but aggressive and exploitative approaches to a nationalist management of the economy that largely rejected the principles of globalism.

In contemporary discussions, two alternative paths to the autodestruction of the globalized economy have been identified. The first sees an inherent flaw in the system itself: in contemporary terms, the most frequently identified issue is the volume and volatility of capital movements. In this version, there may be a system, but it is inherently unstable and likely to produce radically destabilizing booms and busts rather than smooth development. The second explains the crisis of globalization in terms of the social and political responses and reactions it provokes. In this account, fear disrupts globalization.

First, then: can our system autodestruct? Many critics worry that an unreal financial economy has dwarfed the transactions of the “real” or “underlying” economy in which goods and services are exchanged. “Casino capitalism” builds up more bets on future outcomes than there are actual outcomes and diverts resources, time, energy, and emotions from real production and true satisfaction. The resources of official institutions, such as central banks, are hopelessly limited in relation to the enormous size of the currency markets. The international monetary system depends on the bets undertaken there, yet they create a great vulnerability. They can destroy countries as speculators scent a potential gain to be made in generating a self-fulfilling doomsday scenario. This was the story of the crisis that began in Thailand in 1997 and then swept across much of Asia. It is not just individual countries that are vulnerable. Ultimately, such bets might bring down the whole system, since they are predicated on a very narrowly conceived model of rationality.

A model for such a breakdown—in the eyes of many critics an anticipation of the final collapse of the financially integrated global economy—is to be found in 1998, with the collapse of the strategy adopted by the New York–based company Long Term Capital Management. That strategy had depended on what was termed a “convergence play”: the increased convergence of interest rates in major economies, making residual risk premiums appear unjustified. When a global financial crisis seemed imminent, with the spread of crisis from Asia to Russia and Brazil, interest rates suddenly diverged, and the hugely leveraged positions built up by LTCM generated huge liabilities.

A major financial crisis can have systemic effects and catastrophically undermine the stability of the institutions that make global interchange possible. Such a picture, in which financial volatility destroys the system that was built up on the basis of a free flow of capital, has become increasingly worrying to many thoughtful analysts. Even thinkers close to the modern consensus about the desirability of liberalization have drawn back and wondered whether there might not be a case for controlling capital flows. When the Malaysian prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, responded to the Asian crisis with such control measures, he was at first widely ridiculed. But the Malaysian economy stabilized, and gurus of the international economy such as Joseph Stiglitz—at the time chief economist of the World Bank—and Paul Krugman, then an MIT professor and a hot favorite for a Nobel Prize in economics, soon advertised their conversion to the cause of controlling capital movements.1 This plea was supported by market practitioners, including some such as George Soros who appeared to be among the most favored beneficiaries of casino capitalism. At the height of concern about global financial meltdown, Soros predicted the “imminent disintegration of the global capitalist system,” which would “succumb to its defects.”2 The diagnosis was shared by men who had held positions of great responsibility in the international economy, such as the former Federal Reserve Board chairman Paul Volcker. The British philosopher John Gray called for a “reorientation of thought,” since free markets are “inherently volatile institutions, prone to speculative booms and busts.”3 According to this new uneasy critique of financial globalism, continued unregulated capital movements would be the mechanism whereby the liberal international order would destroy itself through its own contradictions (to borrow a phrase widely used in Marxist analysis).

The second path to disintegration lies not in the mechanism of the international order, but in the resentments that the injustices of the global economy may provoke. World injustice was the focus of the street protests in Seattle in 1999 and in Washington, D.C., in 2000. Thomas Friedman devoted a large section of his book on globalization to the “backlash.” He explained: “What all the backlash forces have in common is a feeling that as their countries have plugged into the globalization system they are being forced into a Golden Straitjacket that is one-size-fits-all.”4 There are clear historical precedents. In particular, the economic historians Kevin O’Rourke and Jeffrey Williamson have recently discussed the “globalization backlash” engendered by the nineteenth-century wave of integration—both against goods markets and, most important, against international migration. In their analysis, globalization and the shifts in incomes that it entailed produced relatively speedy reactions—more trade protection, and control of immigration—that eventually strangled the process of integration. The consequence of a free flow of factors of production was that owners of land in previously land-scarce Europe lost, as did owners of labor in the previously labor-scarce New World. The European landowners and the New World laborers had substantial political power, which they increasingly used to limit the extent of globalization and of the troubling factor flows. O’Rourke and Williamson give a rational, interest-based account of how grievances against globalism build up. In an account of the nineteenth century with obvious and frightening contemporary echoes, they explain how trade and migration affected income distribution, and in particular how it contributed to a lowering of incomes for unskilled workers in dynamic countries of immigration (notably the United States).5

A third path—the one taken in this book—examines the same process from a less rational angle. It suggests that globalism fails because humans and the institutions they create cannot adequately handle the psychological and institutional consequences of the interconnected world. Institutions, especially those created to tackle the problems of globalism, come at particular moments of crisis under strains that are so great as to preclude their effective operation. They become the major channels through which the resentments against globalization work their destruction.

This book focuses on the institutions that evolved to handle globalization and its consequences: in the nineteenth century, above all tariff systems, central banks, and immigration legislation. The international world was then managed fundamentally by national institutions, in the framework of a nation-state that many conceived as a safety device or shield against the problems of the international economic order. In the interwar years, as the threat grew bigger, some governments believed that the globalization issues were better handled at an international level: by the League of Nations, its Economic and Financial Organization, the International Labour Organization, and the Bank for International Settlements. In the post-1945 era, a new set of international institutions handled the problems much more satisfactorily than did their predecessors,6 but these have now become the targets for massive criticism from very diverse political and geographic groups: the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization have become the whipping boys of globalization. Some commentators suggest another analogy: that the IMF or the WTO is like a church whose mission is maybe not to remove sin, but to make it psychologically bearable. Finance ministers on this account go into the confessional of IMF “Article IV surveillance meetings,” recite ritual formulas about the ways in which they have erred, and are then reminded of the true doctrine from which they have strayed.7

A great part of this book is concerned with the experience of the world during the Great Depression of the late 1920s and 1930s. This was the time for testing of the first major phase of economic globalization: it was a testing so brutal that the system was destroyed, and the world reverted to autarkic or near-autarkic national economic management. It was only in the 1960s and above all since the 1970s that a global world economy was recreated.

Optimists argue that the depression was a once-only event, one that derived essentially from the consequences of the First World War. Since another sustained and large-scale international conflict of that kind is extremely unlikely, the comforting conclusion is that the Great Depression cannot occur again and should be of interest only to historians, and perhaps also to economists interested in a curiosity cabinet of extreme disequilibria.

The three types of interpretation outlined above (self-destruction, backlash, and weaknesses in institutional regulation) may all be applied to the analysis of the end of globalization in the interwar years with the onset of the Great Depression. The vision of a system collapsing through its own contradictions of course underlay the Marxist interpretation of the experience, which proved exceptionally compelling (especially to intellectuals) and made the brutal doctrines of Communism and its approach to economic management appealing for a generation. But plenty of non-Communists saw international capital movements as a major culprit, and indeed this interpretation, brilliantly formulated by John Maynard Keynes and by Ragnar Nurkse, provided the basis of the post-1945 economic order, the so-called Bretton Woods regime, which aimed at a restoration of trade relations but saw capital movements as destabilizing and undesirable.

O’Rourke and Williamson, though not dealing directly with the Great Depression, see it not as evidence of a systemic flaw but instead as the logical outcome of the pre-1914 “globalization backlash.” They formulate the case very strikingly: “History shows that globalization can plant the seeds of its own destruction. Those seeds were planted in the 1870s, sprouted in the 1880s, grew vigorously around the turn of the century, and then came to full flower in the dark years between the two world wars.”8 They are quite emphatic that it did not require a Great War to produce a Great Depression. This line of analysis had already been pursued by Joseph Schumpeter. In an article on “The Instability of Capitalism,” published in 1928, at the height of the decade’s prosperity, he referred to “the tendency towards self-destruction from inherent economic causes, or towards outgrowing its own frame.” At a moment when there appeared to be no immediate danger of financial turbulence, he argued, “Capitalism, whilst economically stable, and even gaining in stability, creates, by rationalizing the human mind, a mentality and a style of life incompatible with it sown fundamental conditions, motives and social institutions.”9

This book also supports such an analysis: that the pre-1914 international economy, prosperous and integrated as it was, contained severe flaws. Such flaws include those identified by O’Rourke and Williamson, in particular the increased demand for trade protection and the growing hostility in recipient countries to emigration. But the problems went wider, and encompassed a set of expectations about what states and societies should do to limit the impact of globalization that put on the political process an increasingly insupportable burden of expectations.

Before we begin to consider the nineteenth-century wave of globalization, we might contemplate some of the lessons from an earlier age of internationalism: the period of the great explorations, and the creation of large new state forms that prompted analysts to think for the first time in terms of the new concept of sovereignty. The sixteenth century could offer a parable of the perils of globalization.

Interpretations that emphasize the way a mechanism can destroy itself (collapse through its own contradictions) might have a field day with the sixteenth-century experience. The discoveries brought new wealth, but the growth of commerce helped new political centers that subverted the older political units. Spain colonized the New World, but the Netherlands revolted and built a powerful and prosperous new state on the basis of trade. Whether or not the story of Columbus’ sailors bringing back syphilis from the West Indies is correct, new diseases from the New World made Europe unhealthier. Monetary inflation, the product of the large inflows first of gold and then of silver, made prices uncertain and destabilized society. The new moneys paid for larger armies, which then set about their brutal and destructive work.

The conservative Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, in 1933, at just the moment when the Great Depression was breaking civilization down, reinterpreted the cosmopolitanism of the early modern Renaissance as an age of cultural crisis and rebarbarization. The search of the Renaissance for men of action, for the Cesare Borgias, was a sign of profound malaise. “As the albatross is the harbinger of storms,” he wrote, “the man of action always appears on the horizon when a new crisis is breaking.”10

But the sixteenth-century interpretation of the experience of a large world society looked very different from modern accounts of how a mechanism creates strains and backlashes. Contemporaries responded to their new environment with a heightened sense of human imperfection and fragility. “Sin” was the way in which global challenges might be comprehended.

One of the driving forces of both the great religious movements of the sixteenth century in Europe, the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, was a search for a less sinful life. Such reform movements are a highly characteristic response to the features of a universal age, whose characteristics were expressed in a world shaped by religion. Martin Luther, who had a peculiarly heightened sensibility of sin, found the words that allowed the new world to be comprehended. That was the secret of his success. One of his most important early social tracts addressed the problem of commercial life. Trade and Usury, published in 1524, begins with a straightforward declaration of the sinfulness of much commercial activity. “It is to be feared that the words of Ecclesiasticus apply here, namely, that merchants can hardly be without sin. Indeed, I think St. Paul’s saying in the last chapter of the first epistle to Timothy fits the case, ‘The love of money is the root of all evils.’” Where did the sin lie? Not in the buying and selling of commodities that “serve a necessary and honorable purpose,” such as cattle, wool, grain, butter, or milk. It was long-distance commerce, involving the exchange or loss of precious metals, that was pernicious:

But foreign trade, which brings from Calcutta and India and such places wares like costly silks, articles of gold, and spices—which minister only to ostentation but serve no useful purpose, and which drain away the money of land and people—would not be permitted if we had proper government and princes … God has cast us Germans off to such an extent that we have to fling our gold and silver into foreign lands and make the whole world rich, while we ourselves remain beggars.11

The universalism that made many people feel deeply uncomfortable during the Reformation had at least six features:

1. There was constant change. In humanist literature, the spirit of the age was portrayed as Fortuna (rather than as a Christian providence), whose wheel made and broke fortunes. The cult of Fortuna reached a high point in the writings of Machiavelli, who also elaborated the view that the virtuous man had the mission of taming Fortuna. Shakespeare’s plays, in particular the tragedies, can be read as extended meditations on Fortuna.

2. There was contact, mostly commercial, between peoples across large distances. In the sixteenth century this contact most commonly took the form of trading that linked the Europes of the Mediterranean, the Atlantic, and the Baltic. But the most spectacular contacts and conflicts with remote societies were a consequence of the transoceanic explorations and the penetration of European adventurers into completely alien worlds. Cortes and Pizarro confronted non-European civilization.

3. The changeability and the new physical geography produced feelings that the wealth of many other people was illegitimate and could not be justified by the traditional criteria given in the moral universe of that age. The great Augsburg merchant Jakob Fugger, who built up his position by lending money to the Habsburg imperial dynasty, liked to explain that he was “rich by the grace of God”; but in fact he was attacked by clerics as a “sore on the body politic” or as someone who stood “alone in the trough like an old sow and won’t let the other hogs in.”12

4. The changeability and the new physical geography produced feelings that one’s own wealth was illegitimate. Not everyone was as secure as a Jakob Fugger, but even he (and his descendants) gave generously in order to demonstrate the legitimacy of their wealth. Charitable giving generally increased: there were new hospitals, schools, colleges.

5. The changeability and the new physical geography produced feelings that the poverty of many other people was illegitimate. New charities, new poor laws, and new institutions (the hospitalization of the poor) tried to deal with the consequences.

6. The changeability and the new physical geography produced feelings that one’s own poverty was illegitimate. Brigands such as Marco Sciarra built up powerful legends on the basis of robbery ostensibly to help the poor. So-called peasants’ wars swept early modern Europe—with dramatic conflagrations in central Europe in 1525, in France in 1636, 1639, and 1675, in England in 1536 and 1649 (the revolt of the Levellers). These movements usually combined political radicalism with a profound social conservatism: they wanted to restore a lost but legitimate world.

Such dramatic fluctuations produced the widespread belief that traditional values were under threat. Two responses might be formulated: the humanist one, in which virtù tamed Fortuna; or the message of “sin,” in which—as in Luther’s formulation—the existing world was condemned. Nevertheless, it was easier to live with the psychological consequences of dramatic changes, because everyone was quite familiar from the drama of individual existence—the likelihood of sudden catastrophic illnesses or other disasters—with a world that was mutable. The practical outcomes actually resembled each other: the statesman of virtù was supposed to impose his vision on the anarchy of Fortuna, and Luther appealed for a strong state to deal with an amoral world. “Christians are rare people on earth. This is why the world needs a strict, harsh temporal government which will compel and constrain the wicked to refrain from theft and robbery, and to return what they borrow (although a Christian ought to neither demand nor expect it). This is necessary in order that the world may not become a desert, peace vanish, and men’s trade and society be utterly destroyed.”13 The awareness of sin conjured up the state as a way of institutionalizing an adequate response to human error and fallibility.

In economic history, the late nineteenth century is a universal age, in which integration and progress went hand in hand.14 At the beginning of his great novel of the last turn of the century, Der Stechlin, Theodor Fontane describes the remote Lake Stechlin: “Everything is quiet here. And yet, from time to time, just this place comes alive. That is when out there in the world, in Iceland or Java, the earth trembles and roars, or when the ash from a Hawaiian volcano rains down on the Pacific. Then the water here stirs, and a fountain shoots up and falls again.”15 Fontane regarded the changes of his age with an elegiac, sometimes nostalgic pathos. Most of his contemporaries were much more optimistic. But this dynamic and self-confident world was soon to break apart. The breakup destroyed the optimistic belief in cooperation across national boundaries, and indeed in human progress.

At the end of the nineteenth century, the world was highly integrated economically, through mobility of capital, information, goods, and people. Capital moved freely between states and continents. The movement of capital would not have been possible without improved mechanisms for spreading news and ideas. An integration of capital markets presupposed a means of knowing with at least some degree of certainty what was happening to that capital. Markets became interconnected as a result of improved communication. The first transatlantic cable was laid in 1866. The railroad opened up the interiors of continents and created national markets, while the steamship connected the shores of the world’s great oceans. Already from 1838 there was a regular transatlantic service by steamship, although mass goods did not move in this way until the 1860s. In the subsequent decades, refrigeration made the transport of a wider range of foods possible.

Trade was largely unhindered, even in apparently protectionist states such as the German empire. Above all, people moved. They did not need passports. There were hardly any debates about citizenship. In a search for freedom, security, and prosperity—three values that are closely related—the peoples of Europe and Asia left their homes and took often uncomfortable journeys by rail and by ship, often as part of gigantic human treks. Between 1871 and 1915, 36 million people left Europe.16 In the countries of immigration, the inflows brought substantial economic growth. At the same time, the countries left behind experienced large productivity gains as surplus (low-productivity) populations were eliminated. Such flows eased the desperate poverty of, among others, Ireland and Norway. The great streams of capital, trade, and migration were linked. Without the capital flows, it would have been impossible to construct the infrastructure—the railways, the cities—for the new migrants. The new developments created large markets for European engineering products as well as for consumer goods, textiles, clothing, musical instruments.

These interrelated flows helped to ensure a measure of global economic stability. Nearly fifty years ago the economist Brinley Thomas brilliantly demonstrated an inverse correlation between business cycles in Britain and the United States: slower economic growth in Britain helped to make the Atlantic passage more attractive. The new immigrants stimulated the American economy, and hence also British exports, and the British economy could revive.17 Flows of labor and capital, as well as trade in goods, created a general market in which factor prices (the return on capital, land, and labor) were equalized. According to O’Rourke and Williamson, most (70 percent) of real-wage convergence in this period was explained by the integration of labor markets through migration, and the rest by international trade.18

This integrated world bears a close resemblance to our own. In our world also, the returns on capital are increasingly equalized. In rich industrial countries, labor is deeply troubled by the prospect of a globalization-induced lowering of real wages (especially for the unskilled).

Economists who have tried to find a statistical basis for a comparison of this first era of globalization with our own era are usually struck by the degree of similarity. How can we measure international integration? One way is to look at the size of net capital movements. Measured in relation to gross national product (GNP), both the imports and the exports of capital were much greater than today: between 1870 and 1890 Argentina imported capital equivalent to 18.7 percent of national income, and Australia 8.2 percent. Compare these figures with the 1990s, when the respective figures of these large capital importers were a meager 2.2 and 4 percent.19 The story with exports of capital is even more dramatic. On the eve of the First World War, Great Britain was exporting 7 percent of its national income. No country in the post-1945 world has even approached such a level, not even Japan or the pre-1989 Federal Republic of Germany.

The trade comparison is only slightly less dramatic. For most countries, despite all the intervening improvements in the means of transportation, the levels of trade of the prewar world were not reached again until the 1980s. For Britain in 1913, the share of exports in GNP was around 30 percent. The rather lower German figure in 1913 of 20 percent was reached only in the early 1970s.20

But we do not need to look only at figures as an indicator of integration. We may also think of the standardization of the world, whereby railways in civilized countries ran on a track with a gauge of 4 feet 8.5 inches (the Russian empire’s choice of a wider gauge was an early indication that Russia did not wish to follow a Western course). But there was also a standardization of products that anticipated the rise of the McDonald’s hamburger as the icon of globalism. A whole world clothed itself in the cheap (and hygienic) cotton textiles of the type developed originally in Manchester. Women wanted to sew at home with machines made by the Singer Company.

Another approach to globalization is even more impressionistic, and relies on an examination of attitudes to internationalism. The optimism of the age can be used as a testimony to its internationalism or cosmopolitanism. Some analysts believed that the dynamic of integration was so great that it could not be halted by anything—indeed, that it made war between highly developed industrial states impossible. This attractive but eventually illusory proposition was formulated with great brilliance by the British writer Norman Angell in a book published in 1911, and immediately available (such was the extent of global intellectual integration) in fourteen countries and eighteen languages. Capitalists thought that their version of internationalism had made states so dependent on the bond market that they could not afford to give any shocks to business confidence. Socialists believed that the existence of a self-consciously international proletariat could frustrate the plans of the militarists.

The great drive to free trade treaties in the 1860s, which was launched by the Anglo-French treaty (often known as the Cobden-Chevalier treaty), was motivated in large part by commercial considerations, by a contemplation of the gains from trade. But Richard Cobden was a great liberal idealist, and in his belief enhanced commerce would bring peace. The sentiment seems to have been general, for on the conclusion of the Cobden-Chevalier treaty on 23 January 1860, the Prussian ambassador in London immediately reported that the treaty made war between the two countries “impossible.”21

As the integrated, international world evolved it produced a response or reaction—at first an idea, and then the institutional embodiment of that idea. The realization of the implications of a global economy and an international society provoked a strong nationalism. Nationalism means at least two distinct processes. One is the formulation of identities and commonalities in response to an external threat or the perception of a threat. This sort of response can easily tip over into xenophobia. Second, there is a process of institution-building, justified in terms of the first response, in which the nation-state, the typical political construct of the nineteenth century, evolved as a defensive mechanism against threats to stability coming from the outside.

In almost every country globalization almost immediately produced demands for protection from the effects of changes and crises coming from the outside. The nation-state, as we know it, is a response to the challenges of the first wave of globalization. The technical and economic change that came with globalization, and especially with improved communications, made possible the infrastructure of the modern nation-state.22 Telegraphs, improved roads, railways, cheaper and more readily available printed material linked the new form of political unit. The technical changes also created the potential for more military power, and one of the functions of the nation-state was to act as a military protector against the enhanced power of other political units. But the nation-state began to have a new function.

The decades in which the world economy became interconnected were also the period of a gigantic change in political and social assumptions about what the state should do. States in the premodern era had as a primary goal military defense. Modern states were supposed to offer social defense as well. It was in 1863 that Adolph Wagner formulated his “law” of the rising activity of the public sector and the state.23 Expectations about what the state should do rose at the same time as states opened themselves to international trade.24 The new protection may even be regarded as a prerequisite for the process of economic opening, for without it there would have been a harsher and more destructive reaction against the new economic forces. In particular, the state should—it was believed—protect those who were threatened by foreign goods.

The nineteenth-century roots of the later reaction in the interwar period against the international economy can be demonstrated in precisely those three areas that were central to global interconnectivity: trade, migration, and capital movements. The purpose of the new tariffs in the later nineteenth century was often expressed in traditional terms, as not so much social as national defense. In public discussion, most attention focused on grain tariffs. Higher food prices for the consumer might be justified if the result of food protection was to increase the cultivated area, and thus raise the capacity of the state to defend itself in longer struggles against others in the competition of nations. But this argument then shaded into a social variant. Only an army based on a rural population, it was argued, could be effective; and so the farmer had to be preserved as a mainstay of military as well as of social order.

The adoption of protective tariffs in continental Europe was a direct response to the lower freight rates and falling grain prices of the 1870s. The price changes directly affected land prices, and thus the basis of political power in a feudal-agrarian world. Where agrarians were politically influential, they used every possible means of applying pressure and building coalitions for the protection of their interests. In making these coalitions, they reinterpreted the function of the nation-state, in terms of offering security for the victims of global events.

The most obvious response was trade protection, because goods were seen increasingly in national terms. In Britain in the 1880s, an almost hysterical reaction against the allegedly illegitimate competition of German producers focused on highly visible consumer goods, from picture postcards and Christmas cards to toys and musical instruments. The legislative response was a law, the 1887 Merchandise Marks Acts, which required products to be stamped with their country of origin. Similar legislation was soon adopted in many countries. But the protests went on—indeed they were fueled by the labeling. The author of a furious British polemic of 1896, E. E. Williams, who titled his diatribe Made in Germany, complained that when he started to write, he looked at his pencil and saw, to his horror, that it was “Made in Germany.”25 But Germany had an equally nationalistic response, which complained about the British trade envy (“Handelsneid”).26

States also engaged in increased redistribution through the budget in response to greater social expectations of “protection.” In France, social services accounted for 4.3 percent of central government expenditure in 1912, but 21.7 percent in 1928; the comparable figures for Germany are 5.0 percent and 34.2 percent. Correspondingly, total figures for government expenditure rose.27

Exports were often viewed as an alternative to the loss of population. Population policy constituted a key part of politics. It was the foundation for military power, and states with inadequate reproductive capacity, such as Third Republic France, feared that they were losing a military race. An adequate rate of demographic growth was required for economic growth—as the material basis for power—but also simply in order to provide a pool of recruits for armies. But how could this increasing human potential be productively employed? In the 1890s the German chancellor Leo von Caprivi had defended his attempts to liberalize trade policy by saying that the alternative would be pauperization and increased emigration. “We must export. Either we export goods or we export people.”28

In this period, one response to trade crises and financial crises, both in the countries of mass immigration and in some industrial countries, was to restrict the movement of people. Citizenship and nationality, and the entitlements they brought with them, now became central elements in political discussions.

In Australia and the United States lower growth and the financial crises of the 1890s provoked mass protests against immigration. Australia began its strict “white Australia” policy. Americans complained that the new immigrants were replacing skilled native workers.29 In 1897 the U.S. Congress debated a reading test for immigrants. Ten years later, a commission was established to find a way of restricting the “new immigrants” who were allegedly coming only for economic reasons and for a short time. In Canada, farmers protested against “the scum of Continental Europe; we do not want men and women who have behind them a thousand years of ignorance, superstition, anarchy, filth and immorality.”30

Such resentment against foreign migrant workers also gripped some European countries. Germany in particular had become a country of immigration, with over a million foreign workers, especially in mining and in eastern agriculture. There was a clear demand: the Prussian Agricultural Ministry had indeed in 1890 commissioned a study on the feasibility of employing Chinese farm laborers in Germany.31 But simultaneously the efforts to stop such inflows intensified. In 1885 the Prussian interior minister Robert von Puttkamer had ordered the exclusion of Polish temporary migrants, and immigration was rigorously controlled after 1887. The provincial governor of Westphalia ordered “suitable measures” to secure a “drastic” reduction in the number of Poles in the Westphalian industrial area.32 Perhaps the most famous critic of the labor-policy implications of globalization was Max Weber. The arguments that he presented about the distributional consequences of admitting low-skill immigrants have a distinctly modern tone.

The integrated world, he argued, would necessarily produce a general lowering of economic and also of cultural standards. He explained his objections to immigration on the basis of different propensities to consume: since Polish workers were satisfied with poorer nutrition, their employment would be a danger to living standards in richer countries. “There is a certain situation of capitalistically disorganized economies, in which the higher culture is not victorious but rather loses in the existential fight with lower cultures.”33 This type of analysis of the dangers of globalization came to be a feature of the new left-liberal coalition that was forming at the beginning of the century.

What, then, of the third pillar of nineteenth-century globalization, the capital markets? The beginning of globalization in the last half of the century was also the beginning of attempts to regulate and control capital movements, especially when their volatility produced regular and massive financial crises. Capital did not flow in a smooth stream; rather, waves of exuberant overconfidence were followed by speculative collapses. In the 1820s large amounts of British capital went to the new South American republics, but in 1825 there was a default.34 For the next decade, British money went to North America instead. A new wave of lending to South America in the 1850s and 1860s and then to the post–Civil War United States was followed by collapse in 1873. Lending resumed, mostly for infrastructure investments in the 1880s, but there was a new and very severe crisis in 1890. The financial panics produced dramatic effects on the real economies, with output collapses comparable in scale to those that took place in crisis countries (mostly in East Asia) in the 1990s.35

Long-term capital movements were largely unregulated, with the exception of occasional efforts to promote or to block particular bond issues for political reasons. But from the beginning there were attempts to limit or offset the effects of short-term flows on monetary behavior and hence on price levels. The modern view, often forcefully expressed in the 1990s, that long-term movements are beneficial and short-term ones destabilizing, was widely held at the beginning of the age of globalization.

There were two central elements in the new approach to monetary policy: the linkage to the gold standard, and the creation of central banks or the extension of their powers. Before the 1870s, the gold standard as a monetary rule was followed only in Britain and Portugal: the adherence of the new German empire after passage of the currency laws of 1871 and 1873 created a momentum that made this a universal standard. In order to create confidence in their economic management, and thus to attract foreign funds, one country after another subsequently adopted the gold standard rule. It is worth noting that currency and money were more international before the adoption of a common international standard. Silver and gold coins circulated regardless of national frontiers. For instance, in Germany as late as the early 1870s, after national unification, almost a tenth of the coins in circulation were foreign.36 The new currency order was a way of establishing a relationship between a new order of national moneys.

National central banks suddenly appeared to be necessary in order to manage these moneys. Thereafter central banks came to play a decisive part in the management of the monetary consequences of internationalization. The earliest central banks were essentially private creations, responding to a market need for clearing transactions.37 But in the 1870s a new wave of central bank creation began, with a completely different purpose. The gold standard system is often treated in the literature as the high point of political and economic liberalism; in fact the debates about the gold standard and the institutions (notably central banks) that were believed necessary for its operation were about guiding and channeling capital to uses that were felt to be politically, militarily, diplomatically, and otherwise desirable. Russian loans, for instance, were given preferential access to French markets: the Foreign Ministry pleaded for special favoring of France’s strategic ally, the press was bribed (in what a later analyst depicted as “l’abominable vénalité de la presse française”), and investors concluded that Russian government finances had been reconstructed on so sound a basis that default was unlikely. The gold standard was adopted in many countries in order to create international confidence—to be a “seal of approval” for good housekeeping, by limiting the scope for autonomous money creation and fiscal irresponsibility.38 The new policy regime was intended to encourage international inflows of capital. At the same time central banks were established to use monetary instruments to regulate short-term flows and prevent disturbances.

Central banks had an important role to fill precisely because they could guide flows that would otherwise have been automatic. They were a response to financial panics and crises. The crisis brought home the lesson that the world marketplace was dangerous, with the potential to produce sudden and unexpected shifts in income and wealth. Wealthy private individuals or firms might play a part in stabilizing expectations and preventing panics. For much of the nineteenth century, the house of Rothschild took this function. In the United States at the end of the century, J. P. Morgan acted in a similar way; for instance, he put up enough gold to stop the panic of 1896–97. But such—fundamentally beneficial—activity in providing a public good (stability) came under increasing criticism as democratic politics came to be more dominant. Few people were prepared to say that they welcomed the accretion of massive personal fortune, even though such wealth was clearly required if the Rothschilds or Morgans were to play their helpful role. During the U.S. Civil War the Rothschilds and their American agent were subject to bitter attacks from the Republican party.39 After the crisis of 1907, a campaign against J. P. Morgan began, based on the belief that Morgan had taken an illegitimate advantage of the crisis to augment his personal fortune, buying up shares of the Tennessee Coal and Iron company at a fraction of their real value. (Many nevertheless saw this deal as a key to breaking the financial panic of 1907, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who explained with reference to the Morgans that it was “to their interest, as to the interest of every responsible businessman, to try to prevent a panic and general industrial smashup at this time.”)40

In Germany serious debate about a Reichsbank began after the major crash of 1873, in which bank failures destabilized the German economy. But they were also supposed to regulate the inflow and outflow of precious metals. The immediate impetus for the creation of the Reichsbank was the dramatic outflow of gold coinage in 1874. It was at this time that the concept of “guardian of the currency” (“Hüterin der Währung”) began to be used. The international linkages created by gold required a new approach to monetary management.

The older central banks, and especially the venerable Bank of England, began to be much more concerned with their international activities, and with the protection of the British economy from the effects of external flows.

Like its German equivalent, the U.S. Federal Reserve System was born out of financial panic and international crisis. A speculative bubble collapsed in 1907. As New York banks faced demands for the payment of deposits, they restricted payments. In retrospect, most commentators felt that the banks neither needed to nor should have resorted to the suspension of payments that rapidly hit business conditions across the country. The consequence was that the function of lender of last resort needed to be a public responsibility, which could not be left to the presumed benevolence of the large New York private banks. In the past the United States had depended on a foreign liquidity provider of last resort, in complete conformity with the logic of the gold standard regime. In 1907, the crisis in New York and the resulting U.S. demand for gold led to gold outflows and increased discount rates in Europe, especially from London. The British financial system was in effect acting as a pool of liquidity for the United States, providing the functions normally associated with a central bank. When, in response to the 1907 crisis, the Federal Reserve Act came into force in 1914, the United States at last had a national monetary manager.

Other countries drew similar lessons from 1907: that the experience of crisis showed the limits of international cooperation and the need for more effective national intervention and control. In Germany the dangers of overconfidence were already evident in 1907. The atmosphere of panic in the City of London made bankers unwilling to lend, so that it was hard for German bankers to finance themselves in the usual way, and they turned instead to the Reichsbank.41 But the German central bank also felt constrained in its actions in the international panic. On 77 out of 156 days in 1907 on which there was a stock-exchange notation, the Berlin quotation of the Mark exceeded the upper gold point, when gold exports became profitable for arbitrageurs. The reserves of the Reichsbank consequently fell, and the Reichsbank raised its discount rate repeatedly in October and November.42

One result of the 1907 panic in Germany was a new debate about what international action could be undertaken to prevent such worldwide crises of confidence—now made more nearly simultaneous because of the transfer of news through the transatlantic telegraph cable. Some past crises had been overcome cooperatively. In 1890, after a financial breakdown in Argentina and a threat to the London bank of Barings, the Bank of England had mastered the crisis by drawing on support organized by Rothschilds and the Banque de France.43 Again in 1901, France had assisted Britain during the financial turmoils associated with the Boer War; and in 1907 the Banque de France had given an advance to the Bank of England and agreed to discount first-class American bills in order to help the New York market.44 After 1907 Germans saw no possibility of similar actions, in part because of the magnitude and simultaneity of financial crises, but also in part because the deteriorating international political situation made foreign help look increasingly problematic. The 1911 crisis associated with Morocco was a telling example. In any case, Germany had played little part in the central bank cooperation of 1907, while at an early stage of the crisis even the Austrian National Bank had stepped in to supply the Bank of England and the Banque de France with gold.45

For not just goods were now interpreted in a national way, with demands for protection of the national economy. This discussion about national capital had been an important part of the debate about the working of a national institution such as the Reichsbank. The parties of the right feared that an international deflation, the consequence of the general adoption of gold as a monetary standard, would destroy the basis of their economic and political power. They now demanded a “silver wall around our golden treasure.” Money should be national. One Reichstag deputy cited an old song: “What good to me is a beautiful girl, when other men go out promenading with her?”46 When the agrarian leader Count Kanitz demanded interest-rate reductions in the Reichstag, he stressed the necessity of defending against an international danger: “the present crisis is so dangerous precisely because of its international character.”47

With the spread of ideas about protection of goods and labor markets, but also of capital markets, the stage was set for the drama of a Great Depression. The perspectives of 1907 resembled those of 1929 in many ways: the search for more security, more welfare state in Europe and the United States, and more of a defense against predatory capital. But there was no dramatic drop in consumption—as occurred in the later crisis—which might have led to an even more dramatic institutional reordering. For the moment, the nation-state and the national central bank (the newest of which was the U.S. Federal Reserve System) appeared secure as the only possible defense against the harmful or destabilizing consequences of global technical change.

The great critical accounts of the economic transformations of the nineteenth century emphasize not only the tendency to autodestruction inherent in the transformative process of modern economic development, but also the problematical origins of the process. Karl Marx and his followers believed that he was uncovering the laws of motion of economic society. The falling rate of profit and the increased immiseration of the working population would eventually produce a final crisis. The final stage in this crisis was constituted by internationalization. To the extent to which this development played a central role in Marx’s argument, Marx became the first systemic critic of globalism.

In a famous passage at the end of the first volume of Capital, Marx explained his principle of the increasing centralization of control and production. “This expropriation [of the capitalist] is accomplished by the action of the immanent laws of capitalistic production itself, by the centralization of capital. One capitalist kills many.” The result was “the entanglement of all peoples in the net of the world market, and with this, the international character of the capitalistic regime. Along with the constantly diminishing number of the magnates of capital, who usurp and monopolize all advantages of this process of transformation, grows the mass of misery, oppression, slavery, degradation, exploitation.”48

That final crisis also corresponds to a moral crisis, in that the spectacular successes of capitalism were based on previous theft and violence. Marx in his account of the origins of the modern economy gave enormous attention—far more than these episodes really warrant—to the English enclosures, the settlement of Ulster, and the Scottish highland clearances. These are the original sins of capitalism, which will always haunt the system: the economic term for original sin that Marx liked to use was “primitive capitalist accumulation.” Without that accumulation, the product of violence, there would be no dynamism and growth. (In building a socialist society, the Soviet Union took something of this story as a model, and viewed the brutally violent expropriation of the kulaks as “primitive socialist accumulation.”) The products of such brutality were transferred across national frontiers. “A great deal of capital, which appears today in the United States without any certificate of birth, was yesterday, in England, the capitalized blood of children.”49

In the final stages of capitalism, financial speculation would become ever more prominent and controlling over the real economy. By the third volume of Capital, Marx was exploding with rage about finance capital:

Talk about centralization! The credit system, which has its focus in the so-called national banks and the big money-lenders and usurers surrounding them, constitutes enormous centralization, and gives to this class of parasites the fabulous power, not only to periodically despoil industrial capitalists, but also to interfere in actual production in a most dangerous manner—and this gang knows nothing about production and has nothing to do with it. The [English Bank] Acts of 1844 and 1845 are proof of the growing power of these bandits, who are augmented by financiers and stock-jobbers.50

So far, it might be thought that Marx’s account reads just like many of the countless tracts of the 1990s on the evils of uncontrolled global integration. A standard feature of many of the complaints is the power of financial speculators. Even Paul Krugman notes: “No individuals or small groups could really affect the currency value of even a middle-sized economy, could they? Well, maybe they could. One of the most bizarre aspects of the economic crisis of the last few years has been the prominent part played by ‘hedge funds’ … in at least a few cases, the evil speculator has staged a comeback.”51

The evil speculator is a standard figure of all dramas of financial crisis. In the nineteenth century he became almost a stock literary figure, across national frontiers, from August Melmotte in Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now (1874–75), to Friedrich Spielhagen’s Philipp Schmidt in Storm Flood (1877) (both creatures of the panic of 1873), and Frank Algernon Cowperwood in Theodore Dreiser’s The Financier (1912). Politicians eagerly took up the stereotypes. In 1907 President Roosevelt complained that “certain malefactors of great wealth” were attempting to use the panic to destroy his administration’s policies “so that they may enjoy unmolested the fruits of their evil-doing.”52 In introducing one of the score of biographies of the most famous of interwar speculators, the Swedish “Match King” Ivar Kreuger, John Kenneth Galbraith explained of the weaknesses that led to vulnerability in the face of financial crime: “no one should imagine that they were confined in time and place to New York of the twenties.”53 Much of the initial commentary on the depression, even from serious economists such as Lionel Robbins, laid a great deal of the blame on the “proliferation of fashionable fraud” and “speculation.”54 When British prime minister Harold Wilson felt his government’s policies were being undermined in the 1960s, he blamed the “gnomes of Zurich.”

But there is substantially more nuance to Marx’s argument. He was very explicit in developing the religious analogy underlying his analogy:

Primitive accumulation plays in Political Economy about the same part as original sin in theology. Adam bit the apple, and thereupon sin fell on the human race … The capitalist system presupposes the complete separation of the laborers from all property in the means by which they can realize their labor. As soon as capitalist production is once on its own legs, it not only maintains this separation, but reproduces it on a continually extending scale. The process, therefore, that clears the way for the capitalist system, can be none other than the process which takes away from the laborer the possession of his means of production; a process that transforms, on the one hand, the social means of subsistence and of production into capital, on the other, the immediate producers into wage-laborers.55

Richard Wagner’s operatic Tetralogy, the Ring of the Nibelungs, has—as George Bernard Shaw pointed out—considerable parallels to the mental world of Marx. The system is bound to destroy itself, because it was constructed by the gods—chiefly by Wotan—on the basis of laws, which the gods cannot break without undermining the reason for their own existence. Hence the best the gods can do is to reconcile themselves to the inevitability of a collapse. In the critical second act of the Valkyrie, Wotan explodes in frustrated rage and calls for a final cataclysm, “Das Ende.” At the same time, Wotan is obliged to recognize that the world he created is based on theft, even if originally it was someone else’s theft: the dwarf Alberich steals the gold of the Rhine from the Rhine maidens (that is, the state of nature), and then Wotan conspires to steal the gold from Alberich. This was a similar sort of parable to that offered in Marx’s Capital, in which both creativity and crime begin when a dwarf seizes gold from the Rhine maidens and endowed it with a curse. The gold is supposed to bring absolute power; but the dwarf loses the gold to Wotan, who uses it to pay two giants, one of whom then kills the other to steal the gold. The giant, transformed into a huge dragon, is killed by the hero, who gives the ring to a woman, but then seizes it back again when he wants to give the woman to someone else, and is himself killed for the gold ring. Only at this stage do the waters of the Rhine rise up, fill the stage, and allow the Rhine maidens to reclaim the ring from the last murderer. In total, the operas involve seven thefts, one dubious purchase, and one gift (in order to purchase love, which the curse tells us is the one feat that the gold cannot perform). Wagner creates a model of the economy as a flow of goods and services, mediated by gold that is stolen as much as it is traded.

The late-nineteenth-century British conservative politician and thinker Robert Cecil, third marquis of Salisbury, wrote from the standpoint of a reactionary about how the increase of industry and commerce—the striking feature of the globalized world at whose center Britain then was—generated more and more protests about inequality. The new inequalities were particularly hard to bear because, unlike those of a traditional and aristocratic age, they could never appear simply irrational, the product of time, and thus quite independent of the personal merits and endeavors of an individual. In the modern age, Salisbury believed, “the flood of evils wells up ceaselessly.” By the 1880s, he had become bitterly pessimistic:

Vast multitudes have not had a chance of accumulating, or have neglected it; and whenever the stream of prosperity slackens for a time, privation overtakes the huge crowds who have no reserve, and produces widespread suffering. At such times the contrasted comfort or luxury of a comparatively small number becomes irritating and even maddening to look upon, and its sting is sharpened by the modern discoveries which have brought home to the knowledge of every class the doings of its neighbours. That organizer of decay, the Radical agitator, soon makes his appearance under these conditions.

Jealousy on a class basis was, in this semi-Marxist analysis, the inevitable consequence of development and led to “political debility” and “disintegration”—in short, to an end of the world that had permitted the industrial and commercial riches in the first place.56

The stories that the nineteenth century told about the global world built on a secular concept of original sin. The remedy that many thinkers then provided to the illegitimacy of the system echoed Luther’s quite precisely (in a secular manner). Strong public authority was needed to overcome the legacy of that sin. There was a natural community that had been broken apart by creative greed, but the state could create its own order and community, and thus channel the destructive forces of dynamic capitalism. This strategy would offer the only way of avoiding the apocalyptic crises prophesied by a Marx or a Wagner or a Lord Salisbury. A powerful national and political bulwark alone could contain the evils of an unstable world.

Did the guns of August 1914 explode belief in the desirability of international society? It was certainly harder to be optimistic. But after the horrors of the war it was also hard not to have a nostalgic yearning for the internationalism and the security of the prewar world. The hope of the peacemakers was a “return to normalcy”: the old certainties should be restored. But at the same time they should be secured and institutionalized through international institutions, such as the Covenant and the League of Nations, and through treaties, such as the permanent pact of peace concluded at the initiative of U.S. secretary of state Frank Kellogg and French foreign minister Aristide Briand. Such a framework would allow the markets to operate; and indeed international capital resumed its flow. George Grosz in a memorable caricature saw the dollar as the sun that warmed the European continent. Migrations resumed. And markets, it was assumed, would make peace: every observer of the 1920s was struck, for instance, by how dependence on foreign capital imports made eccentric, destructive, and belligerent figures such as the Italian leader Benito Mussolini into responsible and even pacific statesmen.

Rarely had there been so much enthusiasm for internationalism and international institutions as in the 1920s. The standard British textbook on European history of the interwar years concluded, after a long comparison of the virtues of the League of Nations with the flaws of the post-1815 Congress system: “As we balance hopes against fears we may derive some comfort from the study of history which shows that some such organisation as is given by the League is at once necessary, reasonable, and possible.”57

The new League of Nations oversaw financial stabilizations, combining rigorous policy reform imposed from without with economic assistance in a way that anticipated the post-1945 International Monetary Fund. The Bank for International Settlements coordinated the actions of central banks. Trade negotiations were no longer bilateral, as they had been in the case of such famous landmarks of liberalization as the Cobden-Chevalier treaty, but were conducted within a framework of large international conferences, usually organized by the League.

None of these attempts was really successful. Given the catastrophes of the late 1920s, it is tempting to think that an excessive idealism about internationalism may have played a role in the collapse. All the beliefs—part hopes, part illusions—in the restoration of one market-driven world by means of international institutional engineering were destroyed by the experience of the Great Depression. In the 1930s the world descended into economic nationalism and protectionism. There were competitive devaluations. Autarky and war economy became national goals.

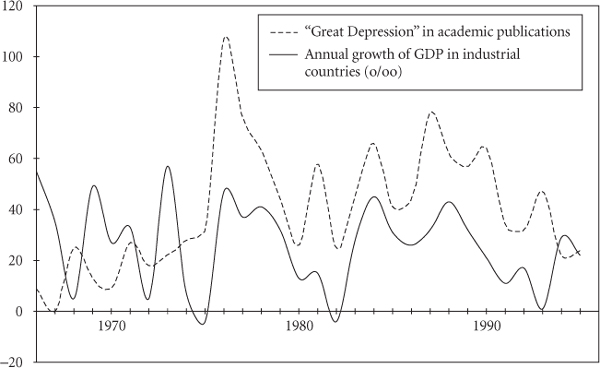

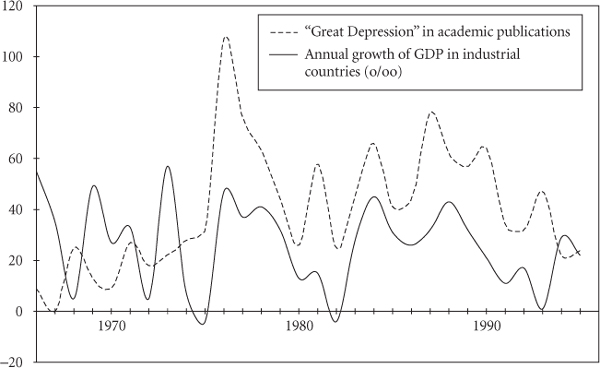

The devastation of that depression still exercises a colossal fascination. In the second half of the century, whenever there was an interruption to growth or a threat to prosperity, many people asked themselves whether we were not once more back in the grips of the Great Depression. In the mid-1970s, the recession that followed from the sudden quadrupling of oil prices was taken as a new world crisis, combining a threat to the economy with a threat to political democracy. The lessons learned from the Great Depression at that time involved the desirability of a Keynesian demand stimulus. At the beginning of the 1980s, a recession in the industrial world and the Latin American debt crisis led to a new wave of pessimistic forecasts, and a new interest in the history of depression. Then the lesson was lower interest rates. In October 1987 in analyzing the stock-exchange collapse, almost every major newspaper printed charts juxtaposing the developments of 1929 and 1987. Again, after the outbreak of an Asian crisis in 1997, and the contagion effects in Russia and then in Brazil, the parallels to 1929 recurred. Helmut Schmidt, who as chancellor in the 1970s had been terrified of the possibility of a replication of the Great Depression, for instance now wrote: “The main parallel lies in the helplessness of many governments, which had not noticed in time that they had been locked in a financial trap, and now have no idea of how they might escape.”58 Academic analysts have loved these parallels too. A chart showing the number of academic articles on the depression reveals a striking parallelism to the economic development of Western economies. We are constantly concerned with the possibility of a repetition of the breakdown of globalization.

In the 1920s previously successful remedies were applied once more. There was a dangerous interplay between monetary policy and trade policy and migration law. In each area, the state needed to respond to raised demands and expectations for state activism; but policy in one area often had to grapple with the consequences of other policies. Monetary policy on an international level was destabilizing. With prices fluctuating more dramatically, the results of tariff protection and other trade policy measures were much more harmful than in the relatively stable prewar world. As monetary policy and trade policy produced suboptimal outcomes, the pressure for restrictions on migration increased.

Figure 1.1 Correlation of journal articles on the Great Depression and general economic conditions

(Sources: calculated from Social Science Citation Index and IMF, International Financial Statistics (Washington, D.C.), various issues)

How and why did the interwar depression turn back the push of globalization? There were high hopes of what the state and the economy might deliver: a wish for prosperity on command.59 The search for new means of securing integration ended in the late 1920s with a series of shocks.

First, since the middle of the 1920s, raw material prices had been falling, in part as a consequence of the extension of the area of production during the world war, in part as a result of inept schemes for price manipulation, such as the Stevenson scheme, which aimed to keep an artificially high rubber price. This price decline made the situation for many capital-importing countries more difficult. But from the perspective of the industrial countries, the results appeared beneficial, since raw materials and foods—at that time a much larger component of household budgets than currently—were cheaper. With additional available income, consumers might buy new products. Such calculations sustained the giddy glitter of the jazz age.

Second, the international political situation in Europe was burdened by an impossible conflict over war debts and reparations. Impossible, because the more credits flowed, the more inextricable the situation became. Germany was supposed to pay a substantial part of the burden of the war through the reparations imposed under the Versailles Treaty. France needed reparations not only to reconstruct, but also to pay the wartime debt to Britain and the United States. Germany—that is, German corporations and the German public sector—borrowed substantial sums largely on the American market; this borrowing financed at least indirectly the reparations payments. But as the payments were made through the second half of the 1920s, it became increasingly apparent that this was not a game that could be played forever: that at one moment, there would come a choice when either the United States could continue to receive reparation payments or U.S. creditors could have their private loans serviced. At least some German policymakers, notably Hjalmar Schacht, president of the Reichsbank, made this calculation in all cynicism, in the belief that the resulting debacle would demonstrate the folly of reparations. The reassessment of the reparations burden in 1929, in which at last a final term was set for the payment of reparation (payments were to continue until 1988), made clear to more investors the impossible nature of their bet, and Germany’s chances of external credit deteriorated dramatically.60

Third, there was a tendency to react to economic problems in the 1920s by trade measures. The model for this was the U.S. Fordney-McCumber tariff act of 1922. It was not that the level of protection was especially high (most analysts now see that the overall level of protection was actually lower than before the First World War). But the possibility that such measures might be applied in response to other, financial problems, and the increased popularity of nontariff protection (quotas) made for a greater restriction of trade. Governments were more responsive to popular pressures because of the extension of the suffrage and the increased level of political mobilization that followed the First World War.

There were plenty of economic problems in the world before the dramatic collapse of Wall Street in October 1929. Australia, with its dependence on exported wool, and Brazil, almost exclusively reliant on coffee exports, were deeply depressed. In Germany cyclical production indicators had already turned down in the autumn of 1927 (the stock market weakness appeared even earlier). What produced the crash of 1929 in the United States is still mysterious, at least for believers in the rationality of markets. What did stock market investors know on “Black Thursday,” 24 October 1929, that they had not known on Tuesday or Wednesday? There had been “bad news” since early September, and the weight of evidence had accumulated to such an extent that there was a panic in the face of the likelihood of the decline of stock prices. The only plausible answer for those who wish a rational account of the stock market collapse is that American investors were contemplating the likelihood of the implementation of a new piece of legislation, which went under the names of Hawley and Smoot. This tariff bill had begun as a promise by Herbert Hoover in the presidential campaign of 1929 to improve the situation of the American farmer (with the agricultural price collapse, the farmer was the major loser of jazz-age prosperity). In the course of congressional debate, however, each representative tried to add new items (there were 1,253 Senate amendments alone). The result—a tariff with 21,000 tariff positions—was extreme protectionism; but worse, until the final narrow vote in June 1930, there was constant uncertainty about the future of trade policy.

But if the story of the depression does not begin with the stock market crash and Hawley-Smoot, neither does it end there. There were some signs of recovery in 1930: stock prices in the United States rebounded, and the lower level of the market made foreign issues appear attractive again.

What made the depression the Great Depression rather than a short-lived stock market problem or a depression for commodity producers was a chain of linkages that operated through the financial markets. The desperate state of the commodity producers along with the reparations-induced problems of Germany set off a domino reaction. In this sense the depression was directly a product of disorderly financial markets.

Is the fragility of the financial mechanism enough to explain the extent of the subsequent economic crisis? The financial catastrophe brought back all the resentments and reactions of the nineteenth century, but in a much more militant and violent form. Instead of a harmonious liberal vision of an integrated and prosperous world, beliefs about the inevitability of conflict and importance of national priorities gripped populations and politicians. They now talked about enrichment at the expense of others—what critics then termed “beggar thy neighbor” or now call a zero-sum approach. The domestic and international tensions that followed destroyed the mechanisms and institutions that had kept the world together, and precluded any effective institutional reform. The reaction against the international economy put an end to globalization.