THE MYSTERY OF THE VANISHING PHILATELISTS

As readers of the Sherlock Holmes stories are well aware, the respectable public image of late-Victorian Britain was a thin veneer over seething excess and wickedness. No one knew this colourful underworld better than Holmes, and his insight into what motivated some of its more extreme citizens enabled him to solve a case that had baffled Scotland Yard’s top people: ‘The Mystery of the Vanishing Philatelists’.

In June 1886, the London papers added the name of Jack Durrant, a married clerk from the parish of Newington St Mary, to the city’s already long list of missing persons. No further details were given, and such incidents were so common that it attracted minimal attention from the Metropolitan Police. If at the time Sherlock Holmes noticed it, he did not mention the fact to Watson.

In early September of the same year, the police showed a good deal more interest in the unexplained disappearance of one Gregory Billings. The reason for their so doing was that Billings, like Durrant, was also a married clerk from the Newington parish. This unusual coincidence drew the attention of the press and set tongues wagging in the Golden Swan, Cranbury Street, where the two were known to meet and where they had last been seen together. According to their wives, both were keen philatelists, founder members of the Newington Stamp Society, which rented one of the public house’s upstairs rooms for its meetings.

Holmes, too, noted the disappearance of the two married philatelists from the same parish. However, apart from making an ironic remark to Watson about the dangers of stamp collecting, he showed no inclination to take the matter further.

Two months passed. Neither Durrant nor Billings reappeared, and a rumour spread among the clientele of the Golden Swan that the pair had run away to Tahiti where, it was said, beautiful young girls threw themselves unreservedly at any foreign man who set foot on the island. John Coleman, the only other regular member of the Newington Stamp Society, mocked such suggestions. Those who made them did not know his friends, he declared. But when asked to give an alternative explanation for the men’s disappearance, he frowned and said he didn’t have one, but ‘something was not right’.

On 5 November, John Coleman learned what that something was. He was not able to pass it on, however, for on that day he too disappeared on his way home to his wife from the Golden Swan. This time the story reached the national press and the Metropolitan Police immediately put two detectives on the case. The following morning, curious to see for himself what was going on, Sherlock Holmes invited Watson to accompany him and took a hansom cab over Southwark Bridge to Newington.

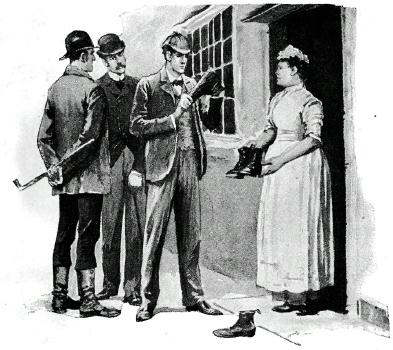

Inspector Lestrade of Scotland Yard was already on the case. He had conducted several interviews with the landlady and regulars of the Golden Swan, but had as yet drawn no firm conclusions. Watson tells us that Holmes met the inspector in the street and offered his services ‘as a discreet assistant’. The inspector politely but firmly rejected the offer, saying he could ‘manage this one very well on his own’.

Holmes accepted the rebuff with equanimity. Rather than returning to Baker Street, however, he paced the routes the three men would have taken from the Golden Swan to their respective front doors. For the first 400 yards or so, the three paths coincided, passing through a dark, foul-smelling court and rounding a rusty gas-holder before dividing in a small square in front of an oriental-style building in stucco and new brick that proclaimed itself the Temple of Christ Revealed. A poster on a board beside the main doorway informed passers-by that the Temple’s current minister was the Highly Reverend Jeremiah St John Woolfstein, ‘a preacher of world renown, over from the United States of America to save the souls of this sinful city’.

Watson writes that the detective read the poster carefully and set out to return to the Golden Swan. Ten yards before the entrance to the court, he found his way blocked by a small crowd. In its centre, standing on a wooden box, was the Reverend Jeremiah Woolfstein himself. He was preaching fire and brimstone of the most lurid kind, stating that those who did not heed his words would be punished ‘even as it is written in the Book of our Lord God’. Unless Londoners ceased their wicked ways and repented of their sins, he warned, ‘the Lord God would surely wipe out their city as he had Sodom and Gomorrah’.

When a woman in the crowd cried out that this was a load of nonsense and the preacher should ‘shove off back to America’, he pointed a finger at her and shouted, ‘Babylon is fallen, is fallen, that great city, because she made all nations drink of the wine of the wrath of her fornication.’ In a voice rising to a hysterical scream, he concluded, ‘Heed the Book of Revelation, wicked woman! The torment of the ungodly is therein writ.’

Several men and women took exception to this, telling Woolfstein he had no right to insult an honest woman. Finding himself losing the sympathy of the crowd, he changed tactic. He smiled broadly, opened wide his arms and said that all honest Londoners would surely be saved if they followed the straight path of the Lord, a path that led directly to Heaven from the Temple of Christ Revealed.

At this, Watson records, Holmes shook his head, turned on his heel and made his way to the nearest bookshop. Once inside, he informed the proprietor that he was in need of ‘some spiritual solace’ and wondered if he might browse the religious books section. The man made no objection.

Three days later, on 9 November, the mystery of the vanishing philatelists took a sudden and ghastly turn for the worse. The citizens of the parish of Newington awoke to hear that the bodies of Durrant, Billings and Coleman had been found in Colombo Street, next to Newington Butts. They had been deposited there at some time during the night, propped in a sitting position with their backs against lampposts. Though the first two were in advanced stages of decomposition, it was clear that all three had been horribly mutilated at the time of death.

Shortly after breakfast, a visibly shaken Inspector Lestrade called on Holmes and asked for assistance. He knew stamp collections were valuable, but he had never come across anyone prepared to murder to get hold of one. He had no obvious leads, and ‘the public were demanding that the perpetrator of these horrible crimes be swiftly apprehended and brought to justice’.

Holmes agreed to help the desperate officer. He declared with a twinkle in his eye that, though he could offer no guarantees, he had one or two promising lines of enquiry to pursue.

First, he examined the corpses of the missing men. The ribs and sternum of Jack Durrant were broken in several places, suggesting the body had been crushed beneath a heavy weight. In contrast, the desiccated remains of Gregory Billings appeared to bear no unusual marks at all. However, peering closely at the wrists with his magnifying glass, Holmes identified a series of minute punctures. A single glance at the body of John Coleman was sufficient to reveal the cause of his death. His feet and the lower part of his legs had been burned away, and the look of unspeakable anguish frozen on his face told that he had died in great agony.

From the mortuary where the bodies had been taken, Holmes went to a local lending library. Here he consulted the final section of a very large and very black King James Bible, and copied out a few verses, together with their numbers, on to a piece of paper. He then returned to Newington to question the wives of the deceased. It was a painful process involving much weeping and commiseration, but in the end he drew forth the answers he needed. Jack Durrant had disappeared on the night of Wednesday 16 June. Mrs Durrant said he had been attending a meeting of the NSS, the Newington Stamp Society, in the Golden Swan. His stamp collection, which he always kept in a leather bag out of the sight of her and the children, was not in the house. As Mrs Durrant had previously explained to Inspector Lestrade, she assumed her husband’s attacker must have stolen it.

Mrs Billings gave similar responses. Her husband had left home on Sunday 5 September to attend a meeting of the NSS in the Golden Swan, a gathering from which he had never returned. His stamp collection, which Mrs Billings had never seen but which her husband always carried in a canvas holdall, was also missing.

Holmes met Watson on his way to interview Mrs Coleman. ‘I feel the noose drawing tighter about the criminal’s neck,’ he confided eagerly. ‘I require but two more pieces of evidence, and I will then be able to hand the matter over to Lestrade to make the arrests.’

Mrs Coleman, whose husband had gone missing just three days previously and who had learned of his horrible death only that morning, was too distressed to discuss her beloved John’s movements with anyone. Fortunately for Holmes, her elder sister, Mrs Winnifred Pollard, who lived just three doors further down the street, was more than willing to talk. Yes, she knew all about her brother-in-law’s membership of the NSS and his attendance at its meetings in the upper room of the Golden Swan. And, no, as far as she was aware, her sister showed no interest in his stamp collection. Mrs Coleman had never actually seen it, though she knew her husband always took it to meetings in a calfskin briefcase.

Holmes thanked Mrs Pollard for her help and walked briskly to the Golden Swan. The landlady, a God-fearing Anglican who refused to serve alcohol on Sundays or saints’ days, was happy to repeat to Holmes all she had already told Inspector Lestrade. She had let the Newington Stamp Society hire her upper room for a monthly fee of two shillings. The society’s three members had kept themselves to themselves and never caused her any trouble.

Had she ever seen their stamp collections?

No, she had not. The men went to great lengths to keep their books hidden. Once, when she interrupted one of their meetings to ask whether she could bring them a cup of tea, Coleman had gone so far as to throw his jacket over the table to hide what lay there.

This did not strike her as odd?

‘A bit, perhaps,’ the woman confessed. ‘But I didn’t mind because they were such kind gentlemen. In fact,’ she went on, ‘several months ago they were good enough to come to my aid.’

Holmes asked her to explain. At the beginning of June, she said, shortly after his arrival in England, the Reverend Woolfstein had begun his mission to London by preaching outside the Golden Swan. The public house, he declared, was a den of iniquity, a cesspool of drunkards and harlots presided over by a shameless servant of the spawn of Rome.

The landlady went outside to protest, asking him to move away. His refusal, accompanied by a stream of biblical invective, was overheard by the three members of the NSS as they arrived for one of their meetings. They immediately came to their hostess’s rescue. They mocked the preacher by quoting bits of the Bible at him. Their knowledge of Holy Scripture surprised her, for she had never seen any of them in church. After a fiery exchange of biblical insults, Woolfstein climbed down from his box and stalked away. The landlady saw Billings try to thrust a leaflet into his hand. The preacher glanced at it, then scowled at his three persecutors before disappearing in the direction of his Temple. As the landlady went back inside, she noticed her gallant rescuers handing out further leaflets to the crowd.

‘Did she see what these were?’ Holmes asked.

‘Not really,’ she replied. She assumed they were invitations to join the Stamp Society because they had NSS in large letters at the top of them.

On hearing this, Holmes thanked the woman for her clear and helpful responses. Half an hour later, having called in at the local library again to check the names of organizations with the acronym NSS, he caught up with Lestrade and suggested he arrest the Reverend Woolfstein and his close followers for murder, and then carry out a very careful search of the Temple of Christ Revealed.

Three months later, Reverend Woolfstein and three of his congregation were hanged for the abduction and murder of Jack Durrant, Gregory Billings and John Coleman.

How had Holmes deduced the guilt of the preacher and his accomplices?

Find the answer/s here.