23

The Phone Call

Ron Resio, former multiple PhD muscleman, died of AIDS in 1984. Bob Hoff, his friend and onetime sex partner, attended the service, a Navy funeral because Ron had served his country. It was the first funeral of someone who died of AIDS that Bob would attend. Later, Bob reached a point where he couldn’t attend another friend’s funeral; by then, he had attended dozens.

In the D.C. area, “five or six guys were dying a week,” Bob recalled. “People would disappear on a daily basis. It was an onslaught.”

In 1984, 3,454 people died of AIDS. It was going to get much worse. More than four times that amount would die four years later, and then the disease exploded globally.

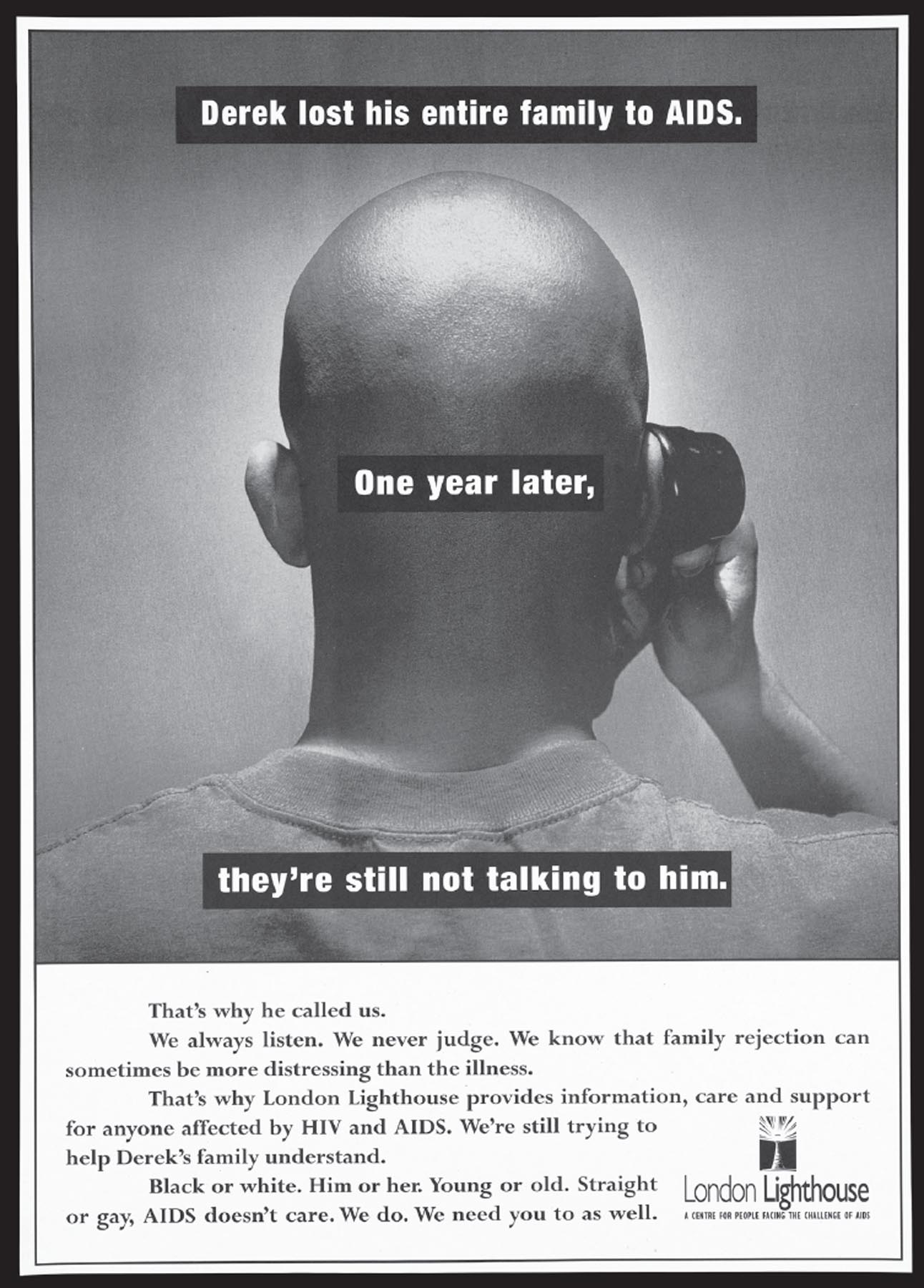

Regularly, Bob said, American gay men would die, and their parents, disavowing their sons’ sexuality, would disown the surviving partner, wouldn’t invite him to the funeral, or would clean out the house and not give the partner his things back. The parents had decided they were self, and the surviving lover was other, an alien in their midst, and that their son had been an alien too, estranged even in death.

AIDS killed and society turned on gay men as if they were nonself, alien. (Wellcome Collection)

This was exactly how members of the prominent gay community in Washington, D.C., felt they were suddenly being treated by President Ronald Reagan. Bob knew all the operatives, who in turn knew Reagan and Nancy, the first lady, and the operatives knew that Reagan liked them; some speculated his son was gay. “We couldn’t believe he flipped on us,” Bob said. Reagan’s administration was widely criticized for its slow response to the AIDS crisis. This turned Bob, a lifelong Republican from Iowa, into a Democrat. Gay men were sick, and other people treated them as if they were toxic.

The community banded together. Bob, a lawyer by trade, had a real estate license. He tried to get gay men to buy property before they became sick “because money speaks.” He wanted them to have some power, a voice. He and his lover at the time had a house on Fire Island, a gay mecca outside New York City that was the setting for weekly dinner parties and sometimes a refuge. At one point a friend who was in the Air Force got booted out for his sexuality and his condition, AIDS, and he showed up at Bob’s house on Fire Island. That night Bob was upstairs in the house when he heard a thump, but he didn’t pay too much attention to the sound at the time. The airman, too distraught to go on, had mainlined cocaine, “committed suicide in my living room.”

One day in 1984, he recalled seeing a guy named Bill who had been “the most beautiful man I’d ever seen.” Now Bill weighed 95 pounds and was a walking purple lesion. Death was everywhere and inevitable.

There really was no treatment, nothing that could be done. The scientists at NIH, led by Dr. Fauci, had thought maybe they could use the bone marrow—the source of immune system cells—of Ron Resio’s twin brother to bolster Ron’s immune system. The idea was that they’d take out Ron’s marrow, which seemed unable to handle the virus, and replace it with healthy marrow that matched Ron’s own. No such luck. “The virus destroyed the transplanted marrow,” Fauci said. It brought certain death.

In late May of 1984, Bob went in for a regular physical. His doctor saw evidence of an irregular heartbeat and sent him for a follow-up. False alarm. He got the news in a phone call at his government office on June 8.

“Bob, I have some good news and some bad news. The good news is, we got a misreading on the heart test. The bad news is, you’re HIV-positive.”

Just like that.

“It didn’t come as a surprise,” Bob said matter-of-factly as he recalled the moment. “I was as exposed as anybody. I realized I was not going to get through it. I had a year or two to live. It was a death sentence, and there was nothing I could do.

“I realized I was just like everybody else.”

He was most certainly not.