46

Bob

Bob Hoff, one of the oldest living asymptomatic HIV sufferers, had fallen deeply in love with one of the longer-living sufferers of HIV who was, by contrast, symptomatic. His name was Brian Baker, the disc jockey and record-store employee mentioned earlier. He had been diagnosed in 1992 and narrowly survived the pandemic thanks to the discovery of the cocktail. By this time, in 2014, they were living together and talking about getting married.

It had been love at first sight, at least for Bob.

That first sighting had been in 2001 at the gay pride parade in D.C., and Bob had seen Brian walking down the street and thought, “Look at that f-ing gorgeous man!” Bob took a picture of him. That seemed to be the end of that. The next year, Bob was in Chicago at the International Mr. Leather contest, and he saw Brian again. Bob’s friends told him to stop being so shy and go up and say hello.

Bob approached, told Brian he’d taken his picture, and then explained to Brian that he liked to paint portraits. “Last year, at gay pride, I took a picture of you. Would you mind if I painted that picture?”

“It was the cheesiest pickup line I ever heard,” Brian said. He fell for it.

They had been together ever since. In 2010, Bob proposed to Brian, and they agreed to marry at some point when it was practical. On November 23, 2015, they were wed at the courthouse in D.C.

Shortly thereafter, Bob went in to the NIH for his usual assessment. He was in the waiting room when Dr. Migueles walked by. Bob jumped and shouted a greeting. He held up his wedding ring. “I finally convinced Brian the timing was right to tie the knot!”

The two men hugged. Then Bob told his wedding story, tears in his eyes.

“I was so, so happy for him,” Dr. Migueles said.

Bob Hoff joyfully settled down and is still alive.

Bit by bit, test by test, Dr. Migueles and the team working at the NIH had spent some twenty years in a painstaking process of identifying the lifesaving quirk in the immune systems of Bob and other controllers. In fact, when Dr. Migueles was first hired, he’d made that inventory of possible mechanisms—strain of virus, number of T cells, genetic profile, etc.—and they’d assiduously gone down the list, eliminating those factors that weren’t sufficiently distinct to explain the issue.

One clue that seemed crucial had to do with the strong association of elite control with the HLA-B57 gene, which is present in 10 percent of the population in North America, but present in about 70 percent of elite controllers. There are numerous HLA genes and genetic variants, so the enrichment of one in particular in this group is striking. HLAs, or human leukocyte antigens, are encoded by HLA genes and are central to the way the body’s surveillance network distinguishes self from alien. HLA, it turns out, has to do with how molecules in the immune system present HIV to the CD8 T cells; those are the soldiers, the fighters, the killers. HLA-B57, compared with other HLAs, might be more likely to present the virus in such a way as to provoke a more effective and lifesaving response. But B57 was not the definitive answer, since up to 30 percent of elite controllers do not have B57 and 10 percent of patients with typical HIV disease carry it.

“Genetics are operative but not sufficient,” Dr. Migueles said they realized. His endgame was much more ambitious: He and the team at the NIH, and other scientists around the world, wanted to create a vaccine for HIV. To do that, they had to know how HLA-B57 was involved in fighting off HIV. Otherwise, they couldn’t reproduce the results. If they could understand the mechanism, “you don’t have to have B57,” he said.

One by one, they ticked off the list of mechanisms they had hypothesized twenty years earlier might explain viral control and be reproducible in some way in the creation of a vaccine.

To understand what Bob is teaching us, Dr. Migueles contrasted him with what we now know about how most people react to HIV. Like Bob, they also recognize and confront the virus. They might even recognize and mount a response to the same pieces of virus. The key difference between the immune responses in patients like Bob and the mainstream way of attacking HIV appears to involve the quality and strength of the response. Bob’s CD8 T cells proliferate, or reproduce themselves, to high levels when they reencounter HIV. As they do so, they increase their killing machinery and load their guns to become even better killers. These serial killers efficiently destroy any infected cells in their midst in a focused fashion. The CD8 T cells from most other individuals with HIV mount a much weaker response and have lower killing ability. HLA-B57 and a few other “protective” HLAs probably predispose a person’s immune system to have this impressive response to the virus in a way that we still do not understand, but one does not need HLA-B57 to develop this major immune system offensive.

So at that point, the immune system makes a calculation that we now know to be central to the very essence of our defense network. It decides whether such a powerful offensive would be worth it. Would it make sense to create an all-out offensive that might destroy HIV but at the risk of creating so much damage to self that it would not be worth it? Should the immune system go nuclear?

No, it should not. At least that’s the calculation, Dr. Migueles explained. The immune system decides that the consequences of such a nuclear war would be “radioactive” fallout—inflammation, autoimmunity, massive internal strife, maybe death.

So the immune system puts on the brakes.

“It gets toned down,” Dr. Migueles explained. “This stunning tolerance mechanism is a way for the host to decide: ‘This fight is too big. It’s a fight that will kill this person.’ So it settles for a less robust response. It cohabits with the virus, thinking, ‘At least it’ll kill me slowly.’ What this research has taught me,” Dr. Migueles continued, “is when you study autoimmune disease or cancer, how many similarities there are.”

The immune system is making trade-offs to keep the peace, to maintain homeostasis, to let the individual live as long as is practical. It’s just math.

Given what they had learned, Dr. Migueles and Dr. Connors started looking for the best approach to a vaccine. One idea was to get the CD8 cell to “ignore the inhibitory signal.” Could they turn off the brakes on the immune system the very way that the cancer pioneers were trying to turn off the brakes so the system would attack cancer?

In theory, yes. But, so far at least, they can’t figure out what molecule or molecular mechanism controls the braking system that is slowing the immune system in its fight against HIV.

There was another way to attack the problem, albeit a long shot.

In 2014, the NIH team helped other researchers take the lymphocytes from an elite controller and infuse them into a late-stage HIV sufferer. This notion was dangerous. That’s because the immune system of the receiving patient might well reject the cells as nonself, just like any failed transplant. It was no small decision to try the experiment. On the other hand, the subject slated to get the cells had a multidrug resistant virus and few options, the kind of person who throughout history has grudgingly welcomed an immune system experiment because the alternative—likely dying anyway—wasn’t so great either.

They took the cells from an elite controller (not Bob) and put them into the patient.

Dr. Migueles got a pleasant surprise. The B27-matched CD8 cells stayed active for around eight days. Plus, the study subject’s concentration of HIV virus dropped twofold before returning to his baseline. “It was safe, and it appeared to have a transient immune effect on the virus,” Dr. Migueles said.

It was a far cry from a cure, though, and the donor cells eventually disappeared. It has its own massive side effects, or potential ones. At the least, it continued to advance the idea that it’s possible to build a mousetrap that is better than the AIDS cocktail.

Bob Hoff offers another lesson, and it has to do with the health of the entire society.

Were it not for people like Bob Hoff, the human species would have been wiped from the earth eons ago for the simple reason that the species cannot survive without diversity. After all, it was the diversity of Bob’s immune system that allowed him to survive.

Imagine previous pandemics—hundreds of years ago, when there was no modern medicine. In those times, in those eras, the diversity of the human immune system gets credit for our survival. Some people didn’t die of the Spanish flu or the Black Plague. Some people had a genetic predisposition, combined with a set of circumstances, that allowed them to survive.

From a purely scientific standpoint, Bob’s legacy hasn’t turned out to be the Holy Grail, not yet the way that Dr. Fauci and Dr. Migueles dreamed it might be. If Bob’s white blood cells—his immune system—hold the key to a more natural way to fight HIV, the researchers haven’t been able to tease it out.

But Bob’s legacy is as powerful a statement as there can be about the immune system and human survival.

This is particularly profound because Bob’s own diverse state—as a homosexual—left him, for most of his life, shunned, an outcast, like so many pitiful souls cursed by an ignorant society for being themselves. Now we can see, though, that Bob’s diversity isn’t just obviously one part of the human mosaic; it is one essential for our survival. The more diversity we have—physically, spiritually, intellectually—the better our balance. Just as in the immune system and microbiome. More diversity, more tools.

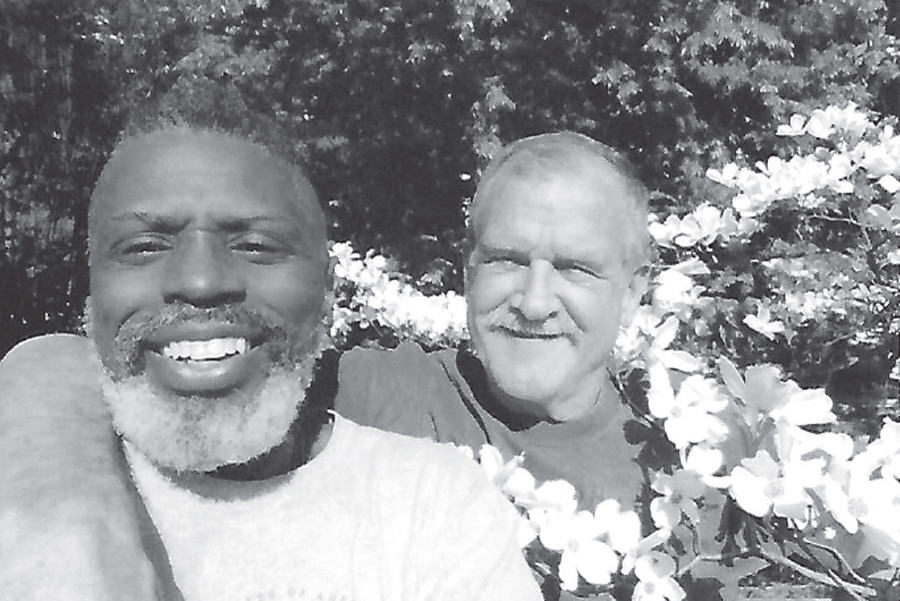

Brian Baker and his husband, Bob Hoff. (Courtesy of Robert Hoff)

Bob makes that point quite powerfully because he was shunned. “The irony or the sheer paradox is so powerful,” said Dr. Migueles. “How unique his immune system is, so beneficial to humanity, and has been, yet he acquired this disease as part of a social subculture who is unjustly received, shunned.”

Diversity in this context has two meanings—one physiological and one cultural—and both play essential roles in survival.

From a physiological standpoint, the broader the genetic pool, the better chance of having someone like Bob who will survive a pandemic and save a species. It’s also a way to have a broader microbiome, and all the benefits of that. If you doubt this, just ask yourself why we don’t allow incest. Such behavior leads to a narrowed gene pool, and survival rates plummet.

But it’s also true that we need a diversity of viewpoints, of ideas. For proof, look no further than the lifesaving medicines I’ve written about in this book. They came from scientists drawn from the world over, bringing different perspectives and theories. Without them and many others, there well might not have been a more than doubling of the human life-span in recent centuries. We have diversity to thank.

Xenophobia, blind nationalism and racism, is an autoimmune disorder. A culture, tone-deaf in its own defense, attacks so aggressively that it puts itself at serious risk. Biology’s lessons, honed like water-polished stone, teach us that cooperation with our species’ diversity is undeniably key to harmony and survival.