Stars That Make Dark Heaven Light

1

“Multiply, vary, let the strongest live and the weakest die.”

— Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species,

Posted in the communal dining hall of the grounded SS Dominion

A dull pounding at my temples told me to take a break. The rich oxygen mixture inside the colony’s greenhouses usually gave me a headache after a couple hours, but I was reluctant to quit just yet.

I liked being here. Diffused sunlight filtered through the translucent ceiling, and regular misting kept the air moist; a blessed relief from the arid climate. I stroked the pollen-laden hairs of my brush against a spray of brackenberry flowers. Unlike the younger kids, I enjoyed the quiet solitude of my daily hand-pollination chores; it was the only time of day I was free from looking after the children.

The rich scent of loam at my feet mixed with the sweet essence of the berry blossoms in my hand, a heady blend made richer in the still air. I stretched my neck, wiped the sweat from my forehead with the back of my hand, and resettled myself on the low stool among the vines.

From outside, I heard the pounding of running feet and clatter of excited voices coming closer, and knew immediately that I was back on duty again. I stood and slipped the pollen brush into the pocket of my apron.

Layfe came tearing into the greenhouse, shouting at the top of his eight-year-old lungs, a baby lapid clutched in each grubby hand. “They’ve hatched, Auntie Ettie! Look, they’ve hatched!”

Behind him, Gehnny, the youngest at five, shrieked with excitement. “Hurry up, Ettie! Or they’ll be gone!”

I grinned and grabbed a handful of coarsely woven sacks from the drying shed. We never knew exactly when to expect the baby lapids to emerge from their unmarked nests beneath Hesperidee’s surface, but when they did, every kid in the colony joined in the hunt.

No one ever tried to locate the nests ahead of time, as a midnight encounter with a broody female stone scorpion was almost always fatal. Lapids could inflict venom with both pinchers and two massive stingers carried scorpion-like above their armored backs.

But the big-eyed babies were adorable, and until their armor hardened, harmless. The other kids were waiting for us in the paved area between the children’s dormitory and the ship. I handed everyone a sack; then Layfe, eager to show us the way, led us screaming outside the Dominion’s barricades. The first day was always the best collecting day; by the third or fourth, the babies had either managed to scuttle off and hide amid the larger boulders out on the range, or had died of extended exposure to sunlight.

He led us to The Cliffs, an area about a mile from the colony, where an outcrop of crumbling boulders as big as a mountain jutted up through the planet’s crust. The rough surface of Hesperidee stretched around us in a stony plain, broken only by grey-green clumps of woody firebite bushes, so named for the blistering effect their oily leaves had on bare skin. Overhead, yellow clouds scudded across skies of palest lavender. In the middle distance, a series of gradually ascending plateaus marked the rims of distant craters.

The cartilage instead of bones in our skeletons necessitated that us kids spend at least six hours each day exposed to the light of the twin suns, Tesla and Newton. After the dry tutelage of the instructional archives and our shifts in the greenhouses each day, we were always eager to be freed from the confines of the colony.

“Got one!” Mia held up her prize.

Nearly all the dangerous predators on Hesperidee were nocturnal, so as long as I was there to supervise, we were allowed to roam anywhere within sight of the ship and barricades.

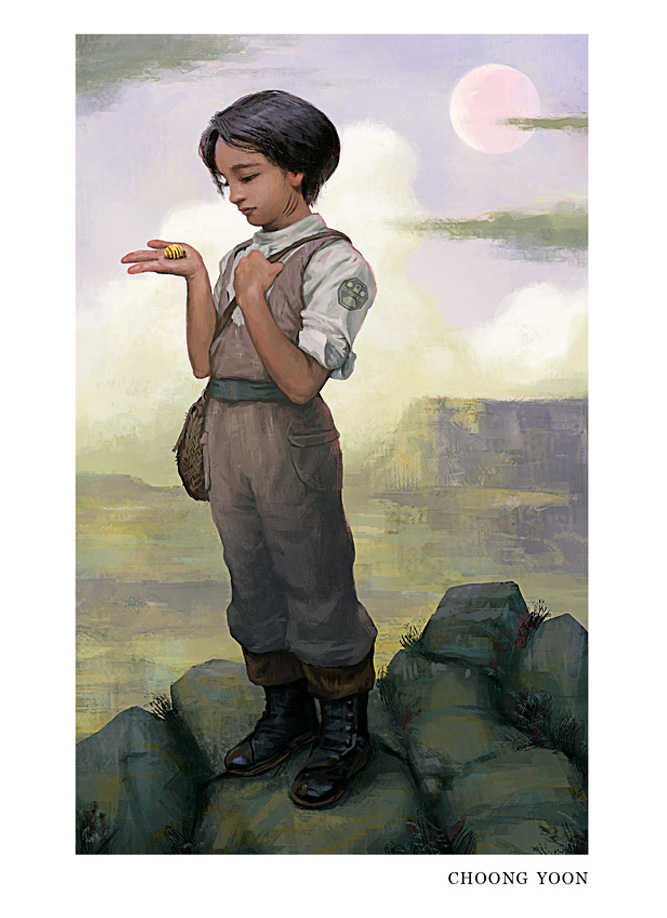

I clutched my sack to my chest as I scanned the broken surface beneath my feet, searching for the slightest movement. Mottled yellow and grey, the leathery shellbacks of newly hatched lapids exactly mimicked the stony surface that covered so much of the land close to the colony. The hatchlings’ instinct to get out of the sun kept them moving. Sometimes the very shapes of their bodies betrayed them. Their still-soft shells weren’t quite as sharp as the surrounding rocky soil. But usually, it was a plump segmented leg, waving as it searched for a foothold among the scree that caught my attention. There.

“I got one, too!” I called.

I picked up the lapid and grinned. About half the size of a ping-pong ball, eight maroon little legs waved at me in helpless lapid fright. A lovely yellow stripe ran around the outer edge of this one’s shell. I’d never seen a striped one before. I shoved it into my sack and kept hunting.

After the initial excitement of collecting, we headed back to Dominion and settled all three hundred and twelve of the babies into shallow bins meant to simulate their rocky habitat in the raising room of the children’s dormitory.

For the next few weeks, they’d be fed a crumbled mixture of soybeans, clippings from the gardens, and local lichens; which would accelerate their growth. After they entered their second pupal stage, we’d move them into the freezers aboard the SS Dominion, as the eight-pound pupae provided the colony’s only source of animal protein for the entire year. The sweet meat had a light flavor and texture.

But before we placed the babies into their bins, Gehnny and I, like every other kid in Dominion, each got to pick out one baby lapid as our very own pet for the season. Sometimes we traded amongst the other kids, but not this year.

This year, I chose the one with the lovely yellow stripe. I had no idea how much that one decision would change my life.

2

“All children are a gift of great value.

No child shall be favored over another.”

Posted in the communal dining hall of the grounded SS Dominion

The excitement of the lapid hatchlings paled against the announcement made by Mother Jean at dinner that night in the colony’s communal dining hall. She stood, tall and sere, her hand resting lightly on her twelve-year-old birth-daughter’s shoulder, until everyone stopped talking.

“I am proud to announce that Daughter Rae has begun her first cycle. She has become a woman. The first of her generation to do so.”

She stared right at me when she said that last part.

The announcement hit me like a physical blow. I blushed furiously. At seventeen, I should’ve been a woman, and a mother, twice over already, but my body hadn’t shown the slightest signs of puberty. My chest was as flat as a boy’s, and I stood no taller than kids half my age.

The whole room applauded, and I joined in, but my heart wasn’t in it. Rae basked in the attention, as each adult in the room spontaneously came forward to kiss her cheek and offer congratulations. Our leader, Father Isaac, announced that Father Lyle would begin immediately to build a new dormitory to house the adults of the next generation.

Resentment flooded through me. In a few months, Rae would be artificially inseminated and move into her new quarters. She’d have her choice of work assignments. As a birthmother, she would have more prestige and a voice in colony decisions. It wasn’t fair.

It should have been me.

Gradually, the hubbub died down and the usual hum of dinner conversation took over.

Mother Bekke, the silver-haired woman seated across from me, leaned over the expanse of the long steel table between us and grasped my hand.

“Don’t look so sad, Henrietta.” Her five pale fingers curled lovingly around my brown, syndactyly-melded three. Among the adults of Dominion, Bekke was well-regarded as a pattern-maker and seamstress. To the children, she was our former full-time nanny and caregiver until five years ago, when the responsibility passed to me. “We have decided to celebrate your womanhood at the coming equinox as well.”

I sat back in my seat, relinquishing her tender touch for the rough pockets of my linen jumper. As the eldest of the first generation of children conceived and raised on Hesperidee, I knew my responsibilities.

“B-but I’m not a woman, yet.”

The excitement on Bekke’s face faded somewhat. “Father Isaac has recently discovered that everyone’s hormone levels seem to be dropping, possibly due to the environmental conditions here. He thinks that’s what may have happened to you.”

I glanced at the head table, where Father Isaac sat. He was the oldest man in Dominion and the colony’s geneticist. He’d been born on Earth, and was the last survivor of the original colonists.

“Why didn’t anyone tell me?”

“When we lost power to the cryo unit last summer, no one fully appreciated what the loss of the sperm and egg bank would mean to the colony. But he thinks once you are bonded with a partner, your hormones will wake up. We simply cannot wait any longer.”

I clutched the wadded cloth napkin in my lap for dear life, unable to believe she was serious. All my life I’d looked forward to the day when I’d be declared a woman, with the right to choose artificial insemination or a partner. I’d already decided to choose artificial insemination for my first child or two. In a few years, I’d marry one of the boys. Layfe or maybe Simon, as soon as they were old enough.

This wasn’t how it was supposed to go. I felt the walls of the crowded dining room closing in on me.

I looked around the room, searching for the truth in everyone’s face. The unnatural yellow light from the ship’s power source gave everything a sickly, jaundiced cast. Every one of the colony’s ninety-six adults looked old and tired; most of the men and all the women had grey or silver-shot hair. Even before the loss of the cryo unit, no children had been conceived in several orbits. Gehnny, the baby of the colony, was now five.

The SS Dominion and the dining room in particular were showing its age too; a fact which couldn’t be blamed on the lighting. After forty years, the portraits of Charles Darwin, Thomas Jefferson, and the great space explorer, Beroe Dunmore had faded; lost their intensity. Less formal, but equally dingy and yellowed inspirational plaques admonished us to remember our priorities:

You cannot escape the responsibility

of tomorrow by evading it today!

Where there’s a will, there’s a way!

We’re all depending on YOU!

“But none of the boys are men yet, either,” I pointed out. The oldest boys, eight-year-olds Layfe and Simon and seven-year-old Kole were too young to father children.

Father Isaac approached our table.

Bekke’s husband, Father Torov, took a deep breath, as if he needed to brace himself for what he had to say. He nodded to the two men sitting next to him. “After testing all the men, Father Isaac says Robert and Lyle have the most viable sperm. You may choose whomever you prefer.”

Both men stood and bowed, red-faced. Stooped and sallow Father Robert, who worked in the ship’s power plant, and slab-faced Father Lyle, the builder. They smiled at me uncertainly.

Father Isaac stood between them, smiling broadly; his mahogany skin crinkled in deep creases around his eyes and along well-worn smile lines in his ancient face. “The important thing is that you spend time with them. Allow them to compete for your affections.”

I fought unsuccessfully to suppress a shudder. The room had gone eerily quiet.

The fourteen other children in the room stared at me in wide-eyed silence. The whole room was watching me. The adults must’ve already known about this.

The sign on the wall above Bekke’s head shouted at me.

BE THE EXAMPLE!

They were depending on me to accept this. I did want to be a mother; I wanted children. If dating two men old enough to be my grandfather was what it took to wake up my hormones and become a woman, I had to try, no matter how queasy I felt about it. The future of the colony depended on it.

It had to work. I had to go along.

It took all my effort to smile, but when I did, the tension in the room seemed to evaporate.

Mother Bekke patted my arm. “Good girl.”

I had never felt so alone.

The rest of the evening passed with interminable slowness. I couldn’t eat. I shoveled beets back and forth across my plate, unable to make eye contact with anyone, least of all, well, anyone. Bekke watched me like a hawk—so did all the other kids.

During dessert, Father Isaac announced that I didn’t have to address Robert and Lyle as “Father” any longer, since they were now suitors for my affections. Kind and well-intentioned as Father Isaac was, he was not a child of the colony. He hadn’t been raised on Hesperidee. He couldn’t possibly understand what I was going through.

I’d known both Father Lyle and Father Robert all my life. The adults raised us to treat all the men and women of the colony as our parents, whether they’d birthed us or not. One big happy family. Considering either of them as a romantic partner was … unthinkable.

Would I be expected to kiss them? Oh god.

If I thought my humiliation for the evening was complete, I was wrong.

I sat, frozen to my seat as Robert bowed and presented me with an ancient book on Desalination Engineering. Not to be outdone, Lyle kissed my hand with his whiskery stubble and offered me a sun-baked bit of clay he’d modeled into the shapely figure of a woman. Not the head or legs; just the body.

I thought I would die of embarrassment.

I thanked them for their thoughtfulness, but couldn’t think of anything else to say. Bekke came to my rescue, and let them know I’d be pleased to spend time with each of them on alternate evenings here in the dining room.

I was finally able to slip away by saying the oxygen saturation in the room was making me dizzy. Bekke knew I was heading outside and said she’d come with me.

After she suited up, she followed me back through the dimly lit grey corridors leading outside while the rest of the colony remained in the dining room, playing games and telling stories to the children.

“Talk to me, Ettie. I realize now that tonight’s announcement must have come as a bit of a shock,” she began. “But we thought it was time. You’re certainly old enough.”

I didn’t say anything.

“Isn’t this what you wanted? To join the adults?”

“Yes, but it feels wrong.” In so many ways.

I waited for her to put on her oxygen helmet. Only four of the adults in Dominion colony had gills; Bekke and Lyle both did. But as children, they’d slept onboard the Dominion in oxygenated quarters, and their lungs never fully adapted to hydrogen, so although they could venture outside for short periods without an oxygen mask, they couldn’t function well, and would die if deprived of supplemental oxygen for more than twenty minutes.

The adult’s dependence on oxygen kept them separate from us most of the time. As frozen embryos intentionally infected with an aggressive transmutation gene virus, Bekke and her peers had been transported to Hesperidee from Earth to help subsequent generations adapt to alien environments at an accelerated pace. The entire mission of Dominion and other space colonies was to pioneer settlements of the human race on other planets.

In contrast, I and all the rest of the kids who’d survived infancy had been born with gills and two sets of lungs, which also enabled us to breathe the hydrogen-rich atmosphere on Hesperidee. None of the children of our generation born without gills had survived more than a few days. Dozens of Dominion’s children had died in infancy before the adults learned this lesson. Father Isaac predicted that all future generations of humans born on Hesperidee would have gills, and no one would think us any different for having them.

We’d been taught to celebrate the differences between us. It was a good thing, which would ensure the survival of the human race. Father Lyle and his crew built the children’s dormitory outside the ship to encourage our bodies to adapt to this planet’s atmosphere, rather than Earth’s.

We looked so different. Sometimes, like now, it was hard to believe we were the same species.

“I know my responsibilities to the colony. I get it. Survival of the human race and all that.” I pushed the panel to release the inner door lock. “But I always thought I’d marry Layfe. Or Simon. They’re more like me.”

She nodded, her expression pained behind the mask.

“I thought so too.” The mask muffled the tone of her voice, sapping all the emotion from her words. “But Robert and Lyle are good men.”

“How can I possibly look at Father Robert or Father Lyle in that way? It can’t work.” I shook my head. “It’s sick. They’re my parents!”

“Technically, Robert and Lyle are not your parents. Yes, we’re to blame for encouraging all of you to think of us that way. Given our current situation, that was a mistake. And I’m sorry for that. But I’m afraid you’ll just have to get over it. You kids are our future, the future of the human race. We’re teetering on the edge of extinction here, Henrietta. There’s no guarantee the boys will mature in the timeline all of us expected. I mean, look at you—”

“Why can’t I just go with artificial insemination?” The thought of one of them touching me, or seeing me naked, nauseated me.

“Honey, don’t you think we’ve already considered that? Your body needs to mature first. Father Isaac thinks you’ve spent too much time around the kids. He thinks the courtship rituals will expose you to male testosterone and put you back on track. Get to know them as real people. This is hard for them, too. You don’t want to disappoint them, do you? The whole colony is depending on you.”

I swallowed my revulsion and nodded. Bekke knew how to get me to agree to almost anything.

“And you need to eat more soy and animal protein. Are you getting enough sunlight?”

3

“It is not the strongest or the most intelligent who will survive but those who can best manage change.”

— Charles Darwin

Posted in the communal dining hall of the grounded SS Dominion

This is Dawah,” Gehnny announced the next morning. Like me, she had chosen a lapid with a yellow stripe. She didn’t want to let poor Dawah out of her hands for even a moment, so already the creature only had five legs remaining. Based on Gehnny’s sole previous attempt at animal husbandry, Dawah would likely not survive his first molt.

We were seated in the girls bunk room in the children’s dormitory; a squat, one-story structure made of local stone, cement, and salvage from the Dominion. The building housed separate boys’ and girls’ sleeping and bathing quarters, a communal living room set up with video ports connected to the SS Dominion’s instructional archives, and a number of spare storage rooms, one of which had been converted into the raising room for the baby lapids.

From her perch on the top bunk, Rae eyed my baby lapid with barely concealed contempt. “I can’t believe you’re keeping another one of those blasted things this year.”

Blasted was not an adult-approved word, but I didn’t say anything. Now that she was officially a woman, Rae seemed determined to rub my nose in it. I cuddled the creature protectively against my chest. “What’s wrong with them?”

She whiffled her throat gills with no little scorn. “When are you going to grow up, Ettie? You are so immature. The only reason they’re letting you participate in a womanhood ceremony is because you’re so old, they don’t know what to do with you.”

The truth in her words echoed the sting I’d felt the previous night; I could only hope the rest of the colony didn’t think the same.

“You’re not a real woman, and you never will be. They feel sorry for you, but I don’t. I can barely stand to be around you anymore.” She heaved herself off her top bunk and stomped out.

I stared after her, shaking my head. If anyone was immature, it was Rae. She’d always been snippy. I’d often had to bite back a retort of my own, knowing that if I said a cross word to her, she’d run off in tears and grab the nearest adult, usually Bekke or her birther, Mother Jean, and claim I’d been cruel to her.

Bekke would frown and tell me how disappointed she was in me. Disappointing Bekke, or any of the adults was something I never wanted to do. I cherished my role as the responsible one. Bekke trusted me with the children; the whole colony did.

But sometimes, being the example wasn’t easy.

“What is his name?” Gehnny asked.

After Rae’s comment, I briefly considered putting him back into the group bins, but decided against it. I wouldn’t give her the satisfaction.

“I’m still thinking.”

The lapid’s stubby digits tickled across the palm of my hand. At this stage, the body was rubbery soft; not much more than a carapace, liquid brown eyes, and sticky feet.

“Ask him.” Gehnny cradled Dawah between her cupped hands and danced across the bunk room to me. “He’ll tell you, if you ask.”

“No, that’s just your imagination.”

“It’s true! Dawah talks to me!”

Gehnny often blurted out such fantasies. No one believed her, of course. Until she reached her name-day, nothing she said carried any weight. But I’d been taking care of her since infancy, and she sounded so certain. I could usually tell when she was making up a story.

“He barely has a mouth. How can he talk?”

She squeezed herself into my lap, her soft brown curls nestled against my neck.

I cuddled her closer.

“Like this.”

She closed her eyes, held the tender creature to her lips, and kissed it. “I love you, baby lapid. Tell me your name. Mmmmm.” As she hummed, the lapid seemed to clutch at her chubby chin with its remaining limbs, as if to return the embrace.

So cute.

She held him close to my cheek, so I could feel a gentle vibration emanating from the creature’s carapace.

She opened her eyes, a smile spreading ear to ear. “See? I told you, his name is Dawah!”

Nona, an impressionable seven-year-old who’d just witnessed Rae’s rude behavior, snorted loudly. “He didn’t say anything, you ninny!” She tossed her head and stormed out of the bunk room in a perfect imitation of Rae. “And Dawah is a stupid name!”

Gehnny’s mouth pursed into a frowning pout.

I kissed and rocked her, soothing her wounded pride. “It’s okay, Gehnny. I believe you. And I think Dawah is a fine name.”

She cradled the vibrating lapid against her neck. “You can do it too, Ettie. Try it.”

I wanted to give my lapid a nice name. Names were important. Last year, it had been Mercutio. The year before, Juliet. Not Romeo; Rae would never have let me hear the end of it. Something more grown-up. Like Shakespeare, maybe. Or Navarre.

Gehnny stared at me with such an expression of yearning, I just couldn’t disappoint her.

“Oh all right. Do I have to kiss him?”

Her whole face lit up. “No. You just have to hum your question at him through your lips. At least for the first few times. Until they learn to speak our language.”

I held my palm up to my chin. The yellow-striped lapid stared at me with what could only be a terrified expression. “Like this?”

Gehnny curled my fingers forward, forcing him closer to my mouth.

“Breathe out softly,” she said. “And close your eyes.”

I obeyed.

The creature seemed to relax. It settled into the palm of my hand.

“Now, say something nice to him.”

I cracked an eye open to see if she was teasing, but she looked as serious as I’d ever seen her.

The lapid tensed.

I closed my eyes again. “It’s okay, little lapid. I won’t hurt you. I love your yellow stripe.”

Velvety toes inched across my palm. So close, I could feel his warmth not-quite touching my lips.

“Now ask him his name in your mind while you hum.”

Mmm. What should I call you, little lapid. Who are you?

The answer came almost immediately, ringing in my brain as clear as if Gehnny herself had spoken.

Vox! Vox. Vox, Vox. Who?

My jaw dropped in amazement. His eyes met mine, and I recognized the intelligence behind his sweet expression.

Gehnny bounced excitedly. “What did he say?”

I stared at him. “He said Vox. I think he wants to know my name, too.”

I pulled him close and hummed against his rubbery skin. Mmm, I am Henrietta.

Etta?

Mmm. Yes.

Like the kiss of a firebite, I felt an immediate bond with Vox. His questions were simple—not words so much, but I could understand his intention. And like a child, persistent.

What place this?

Is safe?

Is food?

He was so curious and had such a quick mind. The more we “spoke,” the faster he learned English. His questions quickly grew more sophisticated, and within a few hours, his vocabulary improved enough so we could mind-speak in conversational English, as long as we stayed in contact with each other.

He liked being held. The humming vibration he emitted represented a contented and receptive state of mind for him.

The other children insisted that they could mind-speak to their lapids too, but Vox was adamant that he was not lapid. He was Tok. And Gehnny’s Dawah was Tok. And Layfe’s Botto was Tok. But lapid was not Tok.

Only the three yellow-striped Tok seemed able to communicate, and even then, only with the child they’d bonded to. We checked the raising bins for more of the yellow-striped Toks, but found no others.

Vox mind-speak to Etta. Botto mind-speak to Layfe. Dawah mind-speak to Gehnny. All Tok mind-speak to each other. ’Umans no mind-speak except to mind-bond Tok.

This was huge. I couldn’t wait to tell Father Isaac and the rest that we’d found intelligent life on Hesperidee after all this time. It was fantastic! I could imagine standing next to Father Isaac as he made the announcement at dinner. He’d have his arm around me. This would be bigger even than Rae’s womanhood announcement.

Rae would go nuts with jealousy.

4

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”

—Thomas Jefferson

Posted in the communal dining hall of the grounded SS Dominion

In all the excitement of communicating with Vox, I completely forgot about my new standing in the colony until dinnertime.

Most evenings, us kids walked over from the nursery block as a group and were given our table assignments after we cleared the air locks. This ensured that all of us kids got equal time and attention from the adults, and vice versa. After being served at the buffet, we would take our assigned seat at one of ten tables for dinner.

But when we arrived for dinner that night, a new table had been added to the room. A small one, covered with a white tablecloth and just two chairs, one of which was empty.

As soon as he spotted me, Father Lyle rose from the other chair and hurried over to offer me his arm.

“Good evening, Henrietta. You look, um, quite vigorous tonight.”

My eyes searched the room, frantic for escape, but there was none. Behind me, I could hear the giggles of Gehnny and Layfe and the others, while the adults all smiled and nodded encouragingly. White-haired Father Isaac even gave me a thumbs-up.

“I will be your dining companion this evening. Allow me to escort you to the buffet.”

Ohgodohgodohgod.

Dazedly, I took his proffered elbow, which brought squeals from the kids behind me.

Father Lyle led me to the buffet table. He must’ve been worried about my stunned silence, because he leaned close and whispered into my ear.

“Actually, Robert and I drew straws on who would get the first date with you, and I won. Tomorrow is his turn. Hope that’s okay. We can switch, if you want.”

He smelled strongly of the herbal soap Mother Anne made of yucca, sage and rosemary. Everyone was watching us. I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. “No. It’s fine. I guess I’m going to have to get used to it.”

The meal passed at a glacial pace. I kept my eyes on my plate, as every time my eyes met the gaze of my dinner companion—or worse, glanced around the dining room—I was met with broad smiles.

Just as I thought dinner had finally come to an end, Gehnny announced that we’d found something new among the latest crop of lapid hatchlings. Talky-Toks, she called them.

“Is this true, Henrietta?” Father Isaac, had instructed us kids to bring any new plant or animal discovery to him immediately. I should have told him before dinner.

I stood. “Y-yes, Father Isaac. I meant to tell you.” Again, I felt the weight of everyone’s stare. “I’m sorry. I forgot.” I explained how Gehnny discovered their ability to communicate telepathically.

“They call themselves Tok. They were left behind as dormant eggs long ago, timed to hatch when planetary conditions improved.”

Rae tossed her hair over her shoulder and rolled her eyes.

“That’s ridiculous,” Mother Jean said.

“No, it’s true!” Layfe shouted. “We can prove it!”

The last pink fingers of sunset were fading from the evening sky by the time the adults finished donning their environmental gear and assembled in the main courtyard outside the kid’s dormitory. Not everyone came, but more than half the colony showed up.

Layfe, Gehnny, and I were excited to show off our new pets. I showed Dawah a pebble I had hidden in my hand and Gehnny correctly guessed the color. Then Father Isaac tried it with other hidden objects between Layfe and Botto, and Vox and me.

When we explained how each Tok mind-spoke to only one of us, nobody spoke. I don’t think they believed us.

Father Isaac didn’t seem convinced, either, although he probed and petted the creatures for quite some time.

“Hesperidee’s stone scorpions have been studied for decades. They’ve never demonstrated any signs of telepathic ability. Most likely, those abilities are coming from you kids. I’m not convinced there’s anything special about these lapids.” He took a few scraping samples of their skin and handed them back to us. “I’ll check the DNA, just to be sure.”

“I knew it had to be a trick,” Rae said.

“No, it’s true,” I protested. “They do speak to us. They’re from an advanced culture. They’re more intelligent than we are, even.”

“It’s getting late.” Father Isaac said.

Gehnny grabbed at his suit. “Ask us to ask them something else. We’ll show you.”

Mother Jean and most of the others began to drift back to the ship, shaking their heads.

“Please, at least let us prove their intelligence,” I begged. “Ask them something you know we don’t know.”

He sighed. “Very well. What is the specific gravity of water on Hesperidee?”

Vox had no answer to that, and Layfe and Gehnny both shook their heads. My heart sank.

“I see.” Father Isaac rubbed the top of Gehnny’s head. “Perhaps we’re asking the wrong questions. Let me think on it a bit. In the meantime, I’ll analyze these samples to see if I can find anything new.”

The rest of the kids followed the quiet adults back to the ship for the usual after-dinner stories, but Layfe, Gehnny and I headed back to the dormitory.

Layfe cupped his hands protectively around Botto. “Why don’t they believe us, Ettie?”

The idea gnawed at me. Admittedly, we’d brought them a pretty fantastic story, and maybe hadn’t thought out the best way to demonstrate the Tok’s abilities. But I hadn’t expected the hostile reaction in the dining hall or the tension among the adults in the courtyard when we gave our demonstration.

And what if they had believed us? What would they have done?

They’d have taken them away from us.

Vox trembled in my hand. All three Tok seemed agitated by their encounter with the adults. They already thought we were huge. I could only imagine what they thought of the giants in their bulky environmental suits and helmets; or Father Isaac as he poked and scraped at them.

“They do. Sort of. Or, at least, Father Isaac does. They just don’t understand what it’s like.”

Having only known Vox for a few hours, I’d already accepted his mind-speak as the most natural thing in the world. Maybe not believing wasn’t such a bad thing, after all. We settled into the common room. Me, on one end of the sofalounge, with Layfe on the other end, and Gehnny on the floor between us.

Vox, are you real? Are the Tok real? Or am I imagining you?

What is imagine? Vox was so curious about everything.

Imagine is wanting the stones beneath my feet to be soft, and thinking it is so.

Stones are ’ard.

Yes. Real stones are hard. Are you real, Vox. Or am I wanting you?

Vox is real. Tok are real. Etta is real.

That night, we spoke, mind-to-mind until dawn. I asked him about the Tok, and he explained that ’Esperidee, which in his language was referred to as a word I couldn’t pronounce, had been just one of many planets settled long ago by his people, who then evacuated after a meteor shower devastated the planet. They left behind several clutches of eggs timed to hatch at intervals after climate conditions improved.

He asked me about the adults, and especially, Father Isaac. I explained that, no, he wasn’t my father. My father had died on Earth, long before I was conceived. I then had to explain the whole human reproductive cycle, including artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization, which, to my own embarrassment, seemed to fascinate him.

When will you molt?

Humans do not molt.

You do not look like adults. When will you molt?

I blushed. No. They birthed us, but our bodies are different. We are born helpless, but as we grow, we change and evolve by growing, not molting. We have two pairs of lungs for respiration. We have gills to breathe the atmosphere on Hesperidee and a nose to breathe oxygen of our home planet, Earth. The adults have smooth, thin skin of many colors, while our skin is thick and brown, which protects us from the suns. The hands of the adults have a thumb and four fingers, while our hands consist of only a thumb and two fused fingers. We are small and fast; and in this gravity, our bones have remained soft. The adults have birthed many other children, but only those like us survived. We are human, but we are new humans. We have evolved beyond our birthers.

Tok also evolve, Vox told me. The first molt is the first evolution. After first molt, you will see Tok are not lapid. In the nymph stage, I will gain much in stature and be able to access more of the ancestral memories of my people. After the second molt, I will become my final form. I will be adult. I will communicate with Tok people and they will come for me.

I fell asleep with Vox cuddled up beneath my neck and dreamed of golden palaces with spiraling towers and handsome sun-browned, men and women.

5

“Man selects only for his own good: Nature only for that of the being which she tends.”

—Charles Darwin, The Origin of the Species

Posted in the communal dining hall of the grounded SS Dominion

The next morning, I slipped Vox into the pocket of my jumper. Like Gehnny, I could not bear to let go of him. With baby lapids and Tok to care for, we needed to obtain fresh food every day. At this stage in their development, the baby lapids preferred the grey lichens which grew in good quantity near The Cliffs.

Dawah, Vox, and Layfe’s Tok, Botto, couldn’t chew the tough dry lichens as well as the lapids. We had to pre-chew the leaves for them, instead of chopping them. The dry grey, leathery leaf fronds tasted a bit odd at first, but it was a flavor that all three of us quickly became accustomed to. A bit peppery, but not at all unpleasant. Once chewed, we’d spit the leaf/saliva mixture into a small bowl and our new charges gobbled it up.

Rae had already moved out of the girl’s dormitory and into one of the storage rooms, which Lyle had converted into private sleeping quarters, just for her, until the new adult residential annex was built. Since neither Rae nor any of us kids could tolerate an oxygen-rich environment for more than a couple of hours, the new adult residence would have dual environmental controls.

At dinner that night, Rae was allowed the same free seating privileges as the adults, while I was again seated at my “private” table in the middle of the dining hall, this time with Robert.

After dinner, Father Isaac announced that he’d completed his preliminary analysis of the yellow-striped hatchlings.

“Based on both the physical and genetic comparisons done between the normal grey Lapidis Laruae hatchlings and the yellow-banded variety, I have determined their DNA to be a 95% match. Physically, at least from the outside, they appear identical except for a minor color variation.

“And while there may have been some minor psychic capability demonstrated, I’m not certain as to the practical value of this ability to us. However, in all fairness, I will continue to give this matter further consideration.”

Layfe looked as embarrassed as I felt, but I don’t think Gehnny understood. Robert chided me for my childish fantasies about talking animals. Bekke caught my glance, and I wondered if the others all thought the same thing.

Fine. I decided to keep all my conversations with Vox to myself.

Over the next few days, the excitement around Dominion Colony gradually settled into a new normal. By day, I tended to the children and our studies, worked in the greenhouses, and in the afternoons, set out with the other kids to gather fresh lichens for the baby lapids.

In spite of what Father Isaac had told us, Gehnny, Layfe, and I refused to believe that the Tok weren’t anything other than what they said they were: descendants of a great civilization whose people would return for them once they were old enough to make the journey back to their homeland. And like all babies, they needed our help to survive.

Father Isaac retested the Tok and the lapids several times. He even had us run them through a series of mazes. The Tok performed so much better than the lapids, even Father Isaac conceded that their problem-solving capabilities far exceeded that of the lapids, but still didn’t fully accept what we told him about their ability to mind-speak.

Once we began adding greens from the garden to the lichens, the lapids and Tok grew quickly. Twelve turns after we found them, the lapids stopped eating and went dormant. We couldn’t help but notice how much larger and plumper our Tok had become compared to the lapids. Four days after the lapids pupated, Vox, Dawah, and Botto each curled into a tight little ball and went dormant as well. We couldn’t even reach them through mind-speak.

6

After sleeping with Vox curled into my neck every turn for the last two weeks, I detested the sudden isolation, but I had little time to think of him. Robert and Lyle had taken the whole courting thing to heart, and seemed intent on claiming my every spare moment.

With our afternoons now freed up from lichen gathering, I’d expected to spend them supervising the kids by hiking and playing games. But now I also had Robert or Lyle as my constant escort, a daily reminder of my responsibility to procreate for the sake of the colony, and to set a good example for the other children. Rae had taken to her new status with a confidence and sense of purpose I secretly admired. She seemed to be looking forward to her coming pregnancy and new living quarters. Why couldn’t I?

I quickly grew to dread the time I spent in Robert’s solemn company, even though our time together was limited, due to the long hours he put in at the power plant. Dinner conversation topics were technical in nature, generally focused on the latest problems in the plant. After dinner, he preferred to sit next to me and hold my hand throughout story hour, when a rotating group of adults read stories to the children.

Lyle, on the other hand, took an entirely different approach. Unlike Robert, Lyle had flexible work hours. Every afternoon, as we emerged from our lessons, I’d find him waiting for me.

“Come with me. I want to show you something.” He tucked my hand into his arm.

Minutes later, I’d be strapped into the passenger seat of one of the colony’s two solar-powered Personal Local Transport Vehicles, and Lyle would take me wherever I wanted to go. I don’t know how he got permission to take the restricted-use hovercraft out on joyrides with me, but he did.

Every day we went someplace different.

I loved it.

We visited the impact crater fields, some twenty kilometers from Dominion Colony. I’d seen pictures of them in the instructional archives, but never by hovercraft. Lyle took me up, up, over the lip and we hovered above the massive impact site for as long as I wanted. He flew the ship parallel to the steep-sided walls, and when I asked, he brought the little craft to rest on the crater floor so we could get out and explore.

That first time, I collected bits of melted glass and broken chunks of meteor created by the impact. Other days, we’d go fossil hunting, or discover the desiccated remains of some predator’s previous meal. Every trip was a new adventure; we never knew what we’d find in the next crater, or over the next ridgeline.

Lyle even taught me how to pilot the hovercraft, which was without a doubt the most fun I’d ever had. It was complicated, but once I got the hang of it, not at all difficult. Sometimes, he’d let me pilot it the whole afternoon.

For an hour or two, I was excused from tending to the children.

It felt strange, at first. Almost as if I’d forgotten something. But as our trips took us farther and farther afield, I began to view these escapes as brief glimpses of freedom. I wanted to know more. To see more.

I searched the instructional archives, looking for the topological surveys for Hesperidee done by the original settlers. I wanted to find evidence of the lost Tok civilization Vox had described. I pushed Lyle to take us beyond even where he had ever ventured before. There was so much I wanted to see.

Even hampered by his oxygen suit, Lyle seemed to enjoy these excursions as much as I did. It became a regular thing for us. And on the nights we dined together, we talked about what we’d seen and found and where we’d go next.

Sometimes, I’d catch the other adults nod knowingly as they watched us make out plans over dinner. I wanted to say, no, it’s not like that—we’re just friends, but I just couldn’t.

Nothing was ever going to happen between me and Lyle. Even without saying it, I think we both understood that. But even I had to admit, we’d become friends. Good friends.

7

“A scientific man ought to have no wishes, no affections—a mere heart of stone.”

— Charles Darwin

From the instructional archives of the grounded SS Dominion

Gehnny was the first to get sick. Within hours, her entire body puffed up like an overstuffed sausage. Tiny blood vessels in her eyes burst; her bloody tears stopped only when she slipped into a coma.

Mother Flor, the physician, could do nothing for her.

Within days, we were all sick to varying degrees. The symptoms started with a fever accompanied by severe body aches and nausea, followed by vomiting and diarrhea, ending in coma and death.

Jonahs, who at six, dreamed of piloting a spaceship like the SS Dominion; and Mia, a sweet darling of a girl who ran faster and could jump farther than anyone, died within a day of the onset of the first symptoms.

Mother Alora, the first adult to die, was followed within hours by Bekke’s husband, Father Torov.

Father Isaac and Mother Flor immediately isolated all the sick, but nothing they did contained the virus. Ten days later, twenty-one adults and six children were dead, including my beloved baby Gehnny, who died in my arms.

I thought I would die of heartbreak. How could I live without her? An orphan like me, I thought of her as my own child. Every time I closed my eyes, her sweet face came to me.

For weeks after, the ghostly voices of dead children called to me in my sleep. I’d wake and rush to them, only to be confronted by the fresh misery of their empty bunks.

A sense of doom settled over the colony. As if the emotional loss was not enough, the virus left a lingering weakness and ache in our joints.

Gradually, as our mobility improved, our grief began to abate. The colony began to return to a slowed-down version of normal. Us kids recovered more quickly than the adults, and returned to our studies. The water and power plants came back online. The laundry and kitchen reopened. Lyle and his men buried the dead in a mass grave a good distance from the colony, and posted bio-hazard signs around the perimeter.

The evening meal, once a cheerful experience for one hundred and eleven people to come together and enjoy each other’s company, now hosted a silent, hollow-eyed group of seventy-five adults and nine children.

Grey with fatigue, Father Isaac reminded us of our duty.

“We cannot allow something like this to overwhelm us. Yes, the loss of our families and friends is painful and disheartening, but our imperative has not changed. Think of Jamestown and the early colonies of North America. Those settlers faced similar disasters, and their colonies rebounded and thrived. We are not done here. We will persevere because we must.”

Mother Jean stood. “It’s those damn Tok. They’re the cause of all this. They’re the only thing that’s changed around here.”

More than a few heads nodded in agreement. Layfe gave me a stricken look. I knew exactly what he was thinking.

But Father Isaac came to our rescue.

“I do not believe the Tok are the source of the illness. Their biology is too dissimilar from ours, and they’ve been dormant for quite a while. The source of this virus could have come from almost anywhere, even from within our own cells. Every one of you was born infected with the HRV2211-A virus, which was designed specifically to mutate aggressively and vigorously. The generational effects of that virus are unknown, and it is possible that a variant of that virus is the culprit here. Or it could be something airborne, in the soil, or simple transference from an infected surface. We may never have the answer.”

But I didn’t like the doubtful expression on Mother Jean’s face. I excused myself early, saying I wasn’t feeling well, and headed back to the dormitory, with Layfe right behind me.

We checked the cupboard where we’d placed the Tok pupae.

Two of the pupae were elongated, heavy, and thicker around than my calf, the third had shriveled like a raisin.

“It’s Dawah,” Layfe said.

It happened to the lapids sometimes. The body inside desiccated into nothing more than a leathery bit of tissue instead of developing. The process took several days, but nothing could be done. Dawah must have died on or near the same day as Gehnny.

I choked back sobs, missing Gehnny all over again. I didn’t think my heart could stand any more losses. Any more death. I thought of the expression on Mother Jean’s face and knew the Tok weren’t safe. I couldn’t lose Vox, too.

“We’ve got to hide them. If anyone wants to take them away from us, this is the first place they’ll look,” I said.

We moved them into a storage closet in the basement furnace room, concealed behind a stack of empty bins. It was clean, dark, and dry, even if not quite the same environmentally as the cupboard in the climate-controlled dormitory.

8

“It’s often just enough to be with someone. I don’t need to touch them. Not even talk. A feeling passes between you both. You’re not alone.”

—Marilyn Monroe

From the instructional archives of the grounded SS Dominion

After three weeks of dormancy, the lapids emerged from their cocoons.

At this stage, the lapid nymphs had morphed into something that might have looked like a distant relative of a soft-shelled crab on Earth. The rounded torso had flattened out to the size of a dinner plate. Their eight legs had lengthened and sported four distinct segments. They moved slowly, using the back four of their eight legs for locomotion. In the front, the first pair of legs was used to shove food into their mouths and the second pair, which were tipped with tiny pincers, used to pluck at vegetation. Their large expressive eyes rested atop retractable eye stalks, and their hatchling shells, while still soft, had developed a more leathery texture. In color, the nymphs remained a pale, mottled grey. Their bodies would not harden into the distinctive mahogany armor of the adults until their final molt.

Grown too large for the raising drawers, they roamed free on the floor of the raising room, fed on a diet of lichen, weeds from the greenhouses, and whatever other vegetation we could find.

Layfe and I checked the Tok pupas several times every day, but there was no change. After three days of waiting, we were both on pins and needles. What if they didn’t emerge? What if the furnace room was too warm? Or too dry?

Finally, on the fifth day, we were working in the greenhouse, and Layfe heard Botto’s summons. “Come on, Ettie—it’s time!”

We dropped our baskets filled with green beans and raced to the dormitory furnace room.

Botto lay panting on the concrete floor. Her gills fluttered from her recent effort, her skin glistened with moisture.

Vox’s pupae had a long horizontal split in it, and I could see his back pulsing gently as he pushed himself clear of the stiff leathery husk. I wanted to help him, but didn’t dare interfere. With a final effort, Vox shoved himself out and away from the stiff outer covering. Blindly, he struggled to untangle his folded limbs, and when he touched my hand, suddenly he was in my mind again. I gasped with relief.

“’Ello, Etta. I am ’ere. What do you think?”

“Oh my God, you can speak!” Not clearly, but understandably, and their speech was undeniably English.

Layfe and I could hardly believe it. The other kids crowded into the cramped furnace room, eager to say “’ello” and touch their caramel-colored skin, so like ours.

They looked so different. For one thing, they had faces.

Each had evolved a somewhat triangularly-shaped head, a proper human jaw, and two auditory slits where ears might be perched atop a single thick neck stalk about three inches long. New eyelids framed their beautiful brown eyes, and while not particularly expressive, their faces appeared undeniably humanoid.

They’d also developed a trunk-like, golden-brown torso; rigid enough to allow them an erect posture. Their hindmost legs had lengthened and jointed in places that mimicked our human legs. Their leg joints and proportions at the hip, knee, ankle, and ball of the foot mirrored those of us kids. Twenty minutes after emerging from their old husks, they could walk on their hind legs. Both Vox and Botto stood about as tall as a three-year-old child. Their two middle pairs of appendages dangled shrunken and useless from the sides of their torso, while their first pair of appendages jutted from their shoulders and ended in a rubbery, two-fingered pincer.

I sent Simon to get Father Isaac and the adults, and we all trooped out into the courtyard to see what the Tok could do with their new bodies.

They could do a lot.

They could run and climb and walk almost as well as we could. When Father Isaac and the others arrived, they were just as astonished as we had been. No one in Dominion Colony could possibly believe that the Tok were lapids anymore.

Father Isaac spoke to them and they were able to understand and answer him. They readily asserted their names, and demonstrated their obvious intelligence by answering as many questions as quickly as Father Isaac and the others could ask them. It felt great to finally be believed, even as I realized what being believed might mean for the Tok.

Some of the adults, like Mother Jean, seemed openly hostile, while Father Isaac appeared overly concerned about the rest of the “Tok Horde” as he called it.

In particular, he asked about what kind of ships and weapons the Tok possessed, what kind of technology they possessed, whether or not they planned to invade Hesperidee, and what they wanted from us.

“Tok cannot answer all ’uman questions at this stage,” Vox answered. “Botto and Vox not yet adult Tok. When Botto and Vox emerge from final pupal stage, we will be fully adult and able to communicate with Tok universal mind. Only then will we be able to summon our people to return for us. Only then will we ’ave answers to the questions you ask.”

This caused a stir among the adults, and I began to get nervous. Father Isaac didn’t seem to notice. He wanted to know more about their biology and adult forms.

“Tok can adapt to any form,” Vox said. “We chose ’uman form to improve communication with ’umans. We ’ear now to improve communication with ’umans. We change our form to match ’umans.”

Not everyone in the Colony liked the idea of the Tok evolving to match humans. Many of the adults, including Mother Jean still blamed the recent deaths on the Tok.

The courtyard had quickly become crowded with adults in their silver enviro suits and plastic helmets, hemming us in. Everyone was talking at once, and the tension was making me uncomfortable. I could feel Vox’s terror, and some of the children were getting upset.

With a quiet word, I instructed Layfe to take Vox and Botto into the raising room with the lapids and get them fed. I then charged Nona and Simon to get the rest of the kids back to the greenhouse to finish up their chores.

I don’t think the adults even noticed when they left.

Someone asked, “So what do we do with them?”

“Stick ’em in the freezer,” Robert said. This suggestion elicited chuckles from some and horrified looks from the others.

I couldn’t believe he could even joke about such a thing. “They’re just babies! You can’t mean to hurt them!”

“They aren’t human, Henrietta,” Bekke said. “They don’t belong here, and I certainly don’t want them in with the children. We don’t know what they’re capable of.”

“No, no.” Father Isaac held out his hand for calm. His face bore deep lines of worry. “You’re right. We can’t just let them wander around inside the compound.”

“You can’t take them away from us,” I said. At that moment, I felt as if the whole colony had turned against me.

Lyle spoke up. “How about they stay in one of the storage sheds? We can set something up so they’ll be comfortable in there, and we can lock it from the outside.”

He held my gaze and I nodded, smiling.

Father Isaac agreed. “That’ll work.”

9

“Intelligence is based on how efficient a species became at doing the things they need to survive.”

— Charles Darwin

Posted in the communal dining hall of the grounded SS Dominion

Father Isaac suggested we treat the undeniably intelligent Tok as guests, saying we had much to learn from each other.

For now, interaction was necessarily limited, as the colony was still struggling to recover after the loss of so many, particularly in the power plant and the greenhouses.

With the adults so busy, they rarely visited the dormitory. The door to the shed was kept unlocked during the day so the Tok could be fed. At this age, much of their waking time was spent eating. I couldn’t see any reason why they couldn’t be fed in the children’s common room during class periods. So I took them there and began showing them the instructional archives.

They were both eager students, and had an ability to absorb new information with startling speed. I started with a timeline of Earth and moved forward through the different eras, biological classifications, and the evolution and major civilizations of man. The evolution and diversity of our architecture in particular, fascinated them. They seemed particularly drawn to the minarets of eastern Europe, the ziggurats of Mesoamerica, and the grandeur of ancient Rome.

Within two turns, they were able to manipulate the archives’ computer terminals themselves and direct their own searches. Along with architecture, Vox’s interests ran to Earth’s technology, and biology.

And space.

Using a map of the solar system, he pointed out the galaxy where the Tok now lived. The instructional archives referred to it as Kepler 4406.

Although some aspects of Tok biology and technology mirrored that of humans on Earth, their universe contained different and diverse elements; and neither Vox nor Botto were able to explain the details of their culture’s technology—not at this stage of their development.

The mind link they shared with their people at this point in their life cycle was one-way. They had access to their own history and culture, as if the events of the past were part of their own memories, but they would not be able to actually converse live with their group mind until they emerged from their next molt as adults.

Father Isaac gathered new DNA samples from each of them and shared his findings one night at dinner.

“I have completed a general analysis of tissues gathered from the Tok creatures after their molt and discovered significant changes in their DNA. In the first sample, the comparison between the Lapidis Laruae hatchlings and the Toks indicated their DNA to be 95% identical. But when I tested the samples taken after the metamorphosis, the similarity between the DNA profiles had dropped to about 60%. The DNA conclusively proves the Toks assertion that they are not lapids.”

The few nods of acceptance around the room were far outnumbered by stony-faced frowns.

“So what are they?”

“What do they want?” asked Rae.

“After spending a good deal of time with them, discussing what they are willing or able to share with us about the Tok, I believe these intelligent creatures are what they say they are: orphans of a past civilization which once thrived on Hesperidee, forced to flee when meteors struck the planet. In addition to their intelligence, they are highly adaptive, and claim a history which predates man. Surprisingly, they seem to have only an ordinary curiosity about us, as merely one of many intelligent species they’ve encountered. They are understandably most concerned with their own safety and survival until they can rejoin their own people.”

Gratified by Father Isaac’s findings, I gazed around the room, but wasn’t convinced everyone else had the same reaction. Some, like Rae’s mother Jean, and my would-be suitor Robert, seemed to find the idea distasteful.

“Until we encountered the Tok, man has never encountered a life form with the ability to alter their own genetic code at will. On a whim, I decided to compare their DNA to some human DNA samples. And while the early sample shared only a 40% match with human DNA, this latest sample is an astonishing 90% match with us.”

A collective gasp filled the room.

Father Isaac nodded. “Yes. They are altering their DNA to match ours.”

Mother Flor, the physician, asked the question everyone was thinking. “What does this mean? For us?”

Father Isaac shook his head. “I’ve asked them individually what they want from us, and they both have the same answer. Their people are a multitude of different physical forms, located on countless different planets, united by a single consciousness. Based on my conversations with them, they seem to consider themselves more advanced than humans. They say they mean us no harm, and ask only for our hospitality until they mature and their ship arrives.”

Robert jumped to his feet. “Why should we trust them? What if this ship is carrying an invading army? We could all be killed. Or enslaved.” He shook his head. “I don’t like this. They’re a danger to all of us.”

Everyone started talking at once. Father Isaac asked Mother Bekke to escort all the minors back to the children’s dormitory. I didn’t want to go, but neither Rae nor I were allowed to stay.

10

After I tucked the children into their bunks, I started to tell Vox what had happened.

“We are mind-bonded, Etta. I experienced everything that happened through our bond. Your people fear what they do not understand. ’Umans are no different than other cultures in this regard.”

Ever since they’d developed the power of speech, both Vox and Botto usually chose to speak their thoughts aloud, even as they were also speaking to us within our minds.

“I’m worried for you, Vox.” I wrapped my hand around his leathery pincer; not so very different from my three-fingered hand. “I want everyone to love you like I do, but I’m not sure it’s possible.”

His liquid brown eyes held mine. “The Tok are not enemies of ’umans. Your Father Isaac understands this. You understand this. Some of the others understand this, too. In time, all the ’umans of Dominion Colony will understand. Do not fear.”

We lay on the grey sofa-lounge in the common room, watching a documentary on Greek architecture from the instructional archive. Vox had curled up comfortably beneath my arm. When the subject of Greek theatre came up, the video panned over the ruins of the famous theatre of antiquity, the Odeon of Herodes Atticus.

“What is fiction, Etta? Is it true or imagination?”

He’d asked me this question several times previously. The concepts of fiction and drama were aspects of human culture the Tok had trouble understanding. With the history of their civilization stored in their memories, they had no need to tell stories. They remembered.

They understood facts, history, science, and even art, but the idea that a recorded event was intentionally not true seemed beyond their grasp.

I tried a different approach. “Fiction is a story. Story is narration about things that might have happened about people who might have once lived. A story can be used as an example to illustrate a lesson or evoke an emotion. It may or may not be true, but it feels true. It feels real.”

“So, fiction is imagination.”

“Well, yes, but it’s more than that.” I had a sudden inspiration. I instructed the archive to bring up Shakespeare.

“Ah yes. The playwright.”

I nodded. “A play is a fiction told by actors. It illustrates a story through their actions.” I sat up, excited to share my most secret pleasure with him.

“This is Romeo and Juliet. It is one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays, and my favorite.” The archive contained dozens of performances, some recorded centuries earlier. I’d seen them all, many, many times. I knew all the scenes by heart.

Fearing he might not understand the original dialog, I selected one of the modern interpretations.

He watched the video in silence, only occasionally glancing at me.

“Why are you crying, Etta?”

“I always cry in this part.” I wiped my eyes with the back of my hand. “He loves her so much; when he thinks she is dead, he would rather die than live the rest of his life without her. And then, when she wakes and finds him dead, she feels exactly the same way.” I sniffed. “It is beautiful. It is a tragedy. I cannot imagine loving anyone that much.”

“But this is not true. This is fiction.”

“Yes, but it could happen. It might have happened. It’s a dramatization. Fiction mirrors life. It is a story you want to believe is true. It feels true, and I believe there are people who experience that kind of love. I wish, I mean, sometimes I wonder what that would be like. To love someone like that.”

His face held little expression, but I sensed his inner struggle to understand. “You would die for love?”

I shook my head. “For me, something like that could never happen. Dominion Colony is my here-and-now. My life is already set in place. I accept that the love I experience will be that of a mother for her children. My responsibility is to preserve the human race through my children. But on Earth, in that time or some other time, yes, it might happen.”

“And that love makes you sad?”

I thought of Gehnny and the other children who had died, and how much I missed them, every single day. “If I could have given my life to save Gehnny’s, I would have. The love for a child is unending.”

“I feel you yearning for this other kind of love. The love of Juliet and Romeo. Yet you say it is fiction.”

“To love someone so completely that you would give up everything, and to have that love returned with equal passion, is a beautiful idea. I cannot imagine a romantic love as powerful as the love between a mother and child, but this story moves me. It makes me believe it is possible. I think most humans who see this play feel the same way. That is the power of fiction.”

“Show me more. I want to understand why ’umans want fiction. What is this fascination with what-might-be-but-is-not?”

We viewed Midsummer Night’s Dream, Hamlet, and then he wanted to see Romeo and Juliet again. This time, I selected a version which preserved Shakespeare’s original dialog. To my surprise, he gripped my hand tightly in the most moving scenes. Afterward, he seemed subdued.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Who do you love, Etta?”

“In Dominion, we’re taught to love everyone equally.” I said the words lightly, but my throat caught. No one had ever asked me that kind of question before. “We love each other and are dedicated to saving the human race, which is more important than romantic love. It’s more important than anything. Nothing else matters.”

“I think it matters to you.”

I blushed. I had no secrets from Vox. “Maybe. Yes. But that’s just wishing.”

11

“We are always slow in admitting any great change of which we do not see the intermediate steps.”

—Charles Darwin, On Natural Selection

From the instructional archives of the grounded SS Dominion

The next morning I went to see Father Isaac. The humming of the DNA purification and extraction units, which I recognized from my previous visits, sent gentle vibrations through the floor as I passed them on the way to Father Isaac’s office.

His lab, two levels above the communal dining hall, was easily as large as the children’s dormitory. The entire space was contained within a single open room. Clear partitions divided the lab into six separate work areas, several of which held an intent scientist conducting experiments or recording their results in the instructional archive.

In his office, I perched on the edge of my seat, our knees almost touching. One wall was covered with built-in, now mostly defunct electronic displays and equipment, once used to monitor atmospheric conditions in space, now repurposed to monitor the weather conditions in the Colony and its surroundings. In one corner, a model of a double helix DNA strand twisted its way toward the ceiling.

“Good morning, Ettie. I don’t often get a voluntary visit from one of you kids. How can I help you?”

“I want to know why I was asked to leave the discussion last night.”

“We didn’t want you to be unnecessarily upset. We all know how you kids feel about Vox and Botto. People expressed their opinions, but no decision has been made. Nothing for you to worry about.”

I sighed. “You announce that I am a woman, but then you send me from the room when the discussion is about something which affects me the most.”

He pressed his lips together, but said nothing.

My pulse pounded in my ears. I’d been wanting to ask this question for a long time. “Am I sterile? If I am, I have the right to know.”

“I wish I had the answer for you, Ettie.” He sounded reluctant to say more. “I believe something in the planet’s flora or in the soil is the cause of the divergence in your blood work. I’m working to isolate the culprit and remove it from the environment. Hopefully, it’s only temporary. We’ll have to wait and see. I’m sorry.”

Divergence. The word sent a stab of fear into my heart. “Why isn’t it affecting Rae? What if I’m sterile?”

“We don’t know that for certain yet. Don’t worry, Ettie. You’ve done a fine job taking care of the children. I don’t see why anything would have to change.”

He leaned forward in his chair and patted my knee. “Conception is only one small part of the equation. We don’t know if any of you kids will be able to conceive, much less deliver a healthy child. We’ve celebrated more than a hundred pregnancies over the last twenty-five years.” He shook his head. “But so few of you survived infancy.”

“There are only nine of us now. It’s not enough, is it?”

“That’s why it’s so important for you to continue your bonding efforts with Lyle. If there’s any possibility.…”

“I don’t have those kinds of feelings for Lyle. It’s not going to work. You’ve got Rae now, anyway. What do you need me for?” I hadn’t intended to sound so bitter.

“Don’t give up, Daughter. It’s only been a few weeks. That virus threw us all for a tumble. I do believe that the presence of male testosterone will eventually make a difference. We must make sure we pursue every avenue. I realize you’re not very happy about Lyle courting you, but the whole colony is depending on you.” He touched his finger to the tip of my nose. “Be the good example we all know you to be. The future of humanity is depending on you.”

12

“Is love a tender thing?”

—William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

From the instructional archives of the grounded SS Dominion

Later, when Lyle asked me to go exploring with him, I told him I didn’t feel well.

“Nothing serious,” I assured him. “Just a stomach ache.”

Which was true, but it wasn’t as severe as I’d made out. My lower back had been bothering me: I felt bloated and uncomfortable. But instead of spending the afternoon on my bunk, I wanted to take the hovership out on my own.

The very idea thrilled and terrified me. Six months ago, I never would have considered touching any of the colony’s equipment without permission. Of course, six months ago, there had never been a reason to ask such a thing, but I couldn’t stop worrying about Vox.

Both of the Tok had grown a lot in the past few weeks. Vox now stood almost to my shoulder, and Botto was only slightly smaller. They’d gained girth as well, and both weighed close to sixty pounds.

The lapids had gone torpid two days earlier, a phase which generally lasted about a month. If allowed to emerge from their cocoons, they would be fully formed, poisonous and nasty-tempered adults; incredibly dangerous, and hard to kill.

Instead, after two weeks, we would humanely move them into the freezers onboard the Dominion. Lapid meat was considered by many to be a sweet, light-tasting delicacy, rich in protein.

I worried about what might happen when the Tok went dormant. Robert and Mother Jean especially had been outspoken in their desire to add the Tok pupae to the freezers as well. Robert kept telling people there was no way to tell how the Tok would evolve in this dormancy period; they could very well emerge every bit as dangerous as the lapids.

Even though Father Isaac assured me that the Tok would not be harmed, I thought it might be safer to take them to the site of their ancestors’ ancient city. That way, they’d be safe while in their most helpless state, and once they emerged, they’d be able to call their people from far enough away to avoid risk to the Colony.

But Layfe had different ideas. We’d argued about it earlier that morning, when we were alone inside the largest of the colony’s six greenhouses. We were propping up the heavy fruit-laden branches of the avocado trees. He wiped his sweaty face on his sleeve and glared at me.

“You heard Father Isaac. Nothing’s going to happen, Ettie. They’re depending on us to take care of them. I’m not going to abandon Botto out in the middle of nowhere. She could get eaten. Or freeze to death. Or dehydrate.”

Layfe and Botto had been as inseparable as Vox and I. Now that they could speak, the other children completely accepted Vox and Botto as odd-looking distant cousins. Only Rae kept her distance, although she wasn’t really one of us anymore.

“Vox says that we can place them in a cavern or bury them. It will keep them safe from predators and the elements. They’ll be fine. You can’t watch her every minute, Layfe.”

A stubborn expression I knew well came over his face. “You can’t tell me what to do anymore, Ettie. Botto wants to stay here with me.”

So that afternoon, with Vox strapped in the seat beside me in the hovercraft, the two of us raced across the rocky terrain, past the weathered cliffs, soda marshes, and craters I’d explored with Lyle. In minutes, we’d traveled farther from Dominion than I’d ever been. He’d never been to the site itself, but he retained a memory of its location.

He seemed completely relaxed. Surprising since this was his first trip in a hovercraft. I could feel him purring in my mind.

“You’re not scared.”

“The sensation of air travel is a shared memory.” He directed me east, toward the lip of the largest crater we’d seen yet.

We flew in a slow spiral up and parallel to the outer walls, our eyes riveted to the top. As the ship crested the rim, I marveled at the sheer size of the impact footprint. According to the ship’s sensors, the diameter of the crater spanned more than a mile. There was nothing to indicate a city of half a million Tok had once lived here.

He gasped.

I reached for his hand. “Oh Vox, I’m sorry.”

“My memories of this place are of how it looked when my people lived here, and the pain they felt as they left this world behind.”

I scanned the floor of the crater, all the while feeling his despair build. Layfe had been right. I couldn’t leave him here. Not like this.

“Let’s go back. There are caves much closer to Dominion which would keep you safe, and I’ll be able to look in on you.”

He nodded. “Thank you, Etta. I am afraid the shock has accelerated my need for dormancy. I must sleep soon.”

I turned west, back toward Dominion. I knew of a crevice in the cliffs near the lichen fields which was big enough. I could seal up the front with stones and he would be safe.

“Tell me, Etta. Will you mate with Lyle? Your mind is not clear on this.”

My heart skipped a beat. “What? Why do you ask?”

“When I wake, I will be an adult. I will call my people and they will come for me. You are my mind-mate. I would bring you too.” His voice sounded strained. His mind, a whirl of undecipherable thoughts.

I grinned at the idea of traveling across the universe to meet the Tok. To live among them and—

No.

I shook my head. “I’m sorry, Vox. I’m not Tok. Dominion is my home. My responsibilities are with the Colony. When I become a woman, I will bear the children of the next generation. The Colony is depending on me.”

“That is what you have been taught. But you are not capable of bearing a ’uman child.”

“Don’t say that! Father Isaac thinks I can.” My hand went to my swollen abdomen, which had been sore to the touch for days. I’d been praying it was going to happen, that I would get my period. That I would finally be a woman. This had to be it. “Why would you say such a thing?”

He fell silent; but I felt the pain in him, and regretted my anger.

“I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have lashed out at you.”

“I understand.” He closed his eyes and was quiet for the rest of the trip. I tried to mind-speak with him, but he refused to respond.

By the time we arrived at the crevice, I recognized the signs of his impending dormancy. A dull glaze covered his eyes; his skin had begun to thicken and darken. His limbs were stiff, and he was heavy now, only a little lighter than me.

All around us, sheer cliffs rose some forty vertical feet above our heads, shading the crunchy gravel beneath our feet. The twin suns had already passed the halfway point of midday, but the narrow vale retained the suns’ heat long after suns-set.

I took him to a particularly narrow place where a horizontal fissure had developed in the cliff face. There was a natural shelf about shoulder height with an opening some five feet wide, two feet high and more than a dozen feet deep. The opposite cliff face was only a few yards away here, so it had a very safe and secluded feeling. I hoped the peppery scent of the abundant lichen growing on the rocks would help him feel at home.

After helping him into a comfortable position deep inside the dusty crack, I began to build up a wall of flat stones and gravel to disguise the entrance. Already, I could feel his mind withdrawing from mine; fading. He was leaving me. I felt a lump rise in my throat.

I wiped my nose on my sleeve. I was being silly. Getting this choked up about Vox going dormant was ridiculous. He was safe and that was all that mattered. And it was only for a few weeks.

Just before I closed off the crevice and sealed him in, he twisted his head blindly toward me one last time.

“I love you, Etta.”

My lips trembled, and I fought the strange, competing emotions welling up within me. I wanted to laugh and cry at the same time.

I could feel his love for me, even as Gehnny’s voice echoed in my head. I could not remember when I’d heard those words from anyone but the children, but there was a different tone to this declaration of love from Vox.

One that made my heart race.

In all our time together it never occurred to me to ask him if the Tok loved, or whether love was a uniquely human emotion. They must, certainly. But here he’d confessed his feelings to me aloud and I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t know how to respond.

And then it was too late. His beautiful brown eyes grew opaque and he was gone. I was alone and empty as a shell.

“Sleep well, Vox.” I love you too.

13

“The smallest worm will turn, being trodden on.”

—William Shakespeare, Henry VI

From the instructional archives of the grounded SS Dominion

Two weeks later, we moved the lapid cocoons into the walk-in freezers onboard the Dominion. I worried that the adults would insist on moving the pupae of Botto and Vox into the freezers as well, but Father Isaac assured me that we still had much to learn about the Tok and promised they would be perfectly safe locked inside the storage shed.

I didn’t say a word. Not a lie, exactly. If they thought Vox was safely locked in the shed, and that made them feel better, who was I to spoil things? I felt better knowing he was hidden in that crevice near the lichen field. Everyone was happy.

The whole colony was involved in making preparations for the upcoming womanhood celebration for Rae and me, and the building of the new private dormitory.

I secretly hoped to join Rae in the ranks of true womanhood before the party.