Half Past

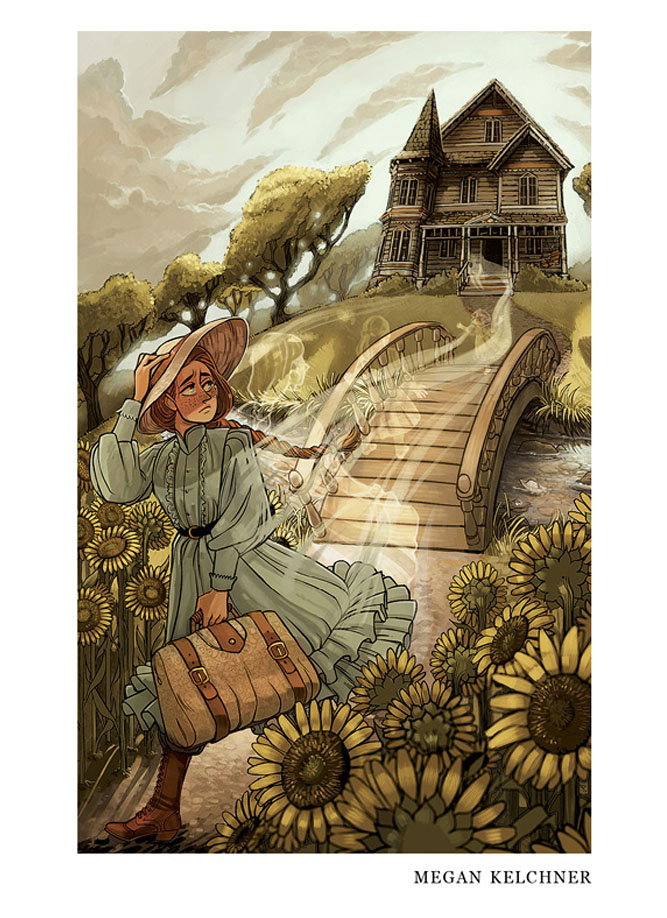

The magic of my father’s house seeped its way into the surrounding countryside. Magic has a way of doing that: overflowing its container, having influences you did not intend. It’s one of the first things I learnt: magic is messy. There were traces in the stream running through the garden; in the translucently clear water and the way it sounded as if it were laughing if you didn’t quite listen. It spilled into the sunflowers growing to the side of the front door; as big as your head and brightly, improbably yellow, they would lean towards you if you talked to them, and rub their petals under your chin with a light, swaying affection.

Today though, it was hot in the garden. Around the back of the house dry leaves crunched under my feet and the plants were overgrown and wilted. I wondered what this said about my father’s mood and how very angry he must still be. Or maybe my eyes were seeing all of the little details more, because I was leaving.

I heard the boards of the porch creak and saw Eliza swinging in the patio seat, the heels of her boots drumming angrily on the downswing.

“What are you doing?” I leaned against the rails and watched her go backwards and forwards.

“What’s it look like?” Eliza was not my favorite Echo—she was almost thirteen and snappy and disconsolate with it. But she had been one of my companions for more than two years, and today I looked at her scowl with an odd sentimental fondness.

“I was looking for you,” I said.

“Why?” she asked abruptly. She stopped swinging though and squinted up at me.

“I guess … to say goodbye.”

“Oh.” She was a little faded these days. She hadn’t aged at all of course, her dark hair hung in the same long braid down her back, but I could see through parts of her dress to the swing behind her. She had been all sharp angles and vivid streaks of scorn in the beginning. “Why?”

“Because I refuse to be stuck in this house forever.” I could feel the heat returning to my words and my cheeks both. “Because just because you have the most magic does not mean you get to control everyone else.” Eliza chewed her fingernail—a habit I’d always had—but kept her eyes on me. “Because he treats me like a child and it is not fair.” I was conscious of the childish note rising up in my voice and the irony didn’t escape me but I did not care. I was fifteen years old, and I had my own magic.

“Good luck out there,” said Eliza, and the softness of the expression on her face surprised me. In the couple of years she had lurked here I hadn’t seen her smile before. I went inside.

I skirted past the sitting room and looked in the sunroom, which was unusually dirty. The windowpanes were streaky with grime so the sunlight coming in was muted, but I only saw a couple of other Echoes who were so faint that if I hadn’t been looking, I wouldn’t have noticed them at all.

The Echoes had been my only playmates for a long time. My father was a stern man, with a fierce hooded gaze like a hawk, and when he directed his attention at you sometimes it felt like your skin would burn with all of the intentness; he didn’t count as a playmate. My mother used to play. She didn’t have any magic, but she had been a masterful weaver of fairytale and fun. She’d had a soft spot for the Echoes, whereas my father usually looked right through them with a certain impatience. They were a frustration to him I think; the fact that I produced them proved that I had inherited a strong talent for magic, but whenever he tried to instruct me in those arts, the results were usually disastrous. The magic with which I made the Echoes was instinctive and unbidden. I failed to do anything on command.

My mother had died when I was nearly seven, and then the Echoes—shades of me, always younger, always receding from me in age and experience—were all I had. My father had no family left, and my Mother’s sister was not spoken of, for reasons I didn’t understand. I had a memory of her visiting when I must have been less than four, my young pretty aunt, spinning me around and around to make me laugh, her eyes dancing.

I found Bethie at last down near the stream. She had made little paper boats, put delicate blue and white flowers inside for passengers and was casting them off at the edge of the water. She jumped up when she saw me and hugged me tightly around the waist. Her thin little arms were surprisingly strong. Her hair trailed down around her face in dark curls.

Bethie was six, and my favorite.

On my sixth birthday my father had magicked little fairy lights that floated in the air all around, and he had even put his arm around my mother in a rare show of affection and smiled down at me. There had been a mound of presents, among them a dollhouse with little people who moved in a jerky manner inside it. There had been a rainbow birthday cake with purple frosting which was sweet and hard on my tongue. That was the day Bethie had appeared, with a sharp smell like ozone, coalescing out of birthday candles and anticipation and glowing excitement, glimmering and forming in the air until she became real and solid. Whenever I was in the grips of an overwhelming emotion I would make an Echo. It was like I was not enough, by myself, to contain what I was feeling. Even when I understood that it was me doing it, it was never something I could control.

The stream was not laughing today. Bethie’s boats sailed prettily in the eddies, but I didn’t feel the sense of impish delight that the water usually had. I gazed back towards the house. Had my father pulled in all his magic to brood within himself and left the house and grounds to suffer? Was he doing it on purpose, to show me how he felt? I felt my own anger kindling back to life. Even with his harshness and distance he was my father, but he could not keep me here cloistered away from everything else in the bright wide world.

And that led back to why I was here.

“I’ve got something to tell you,” I said looking down into Bethie’s small bright face. “I’ve got to go away.” Haltingly I tried to explain, although she was only six and she had crystallized out of a moment where her world was perfect and glowing, so I didn’t know how much she could understand. I don’t know that she or the Echoes really knew who I was anyway. They existed in their own little worlds, timeless, unchanging, caught in a moment, and I think everything else was blurry to them.

“I’ll come with you,” said Bethie when I finished. It was entirely unexpected, and impossible, and melted me like I was birthday candy abandoned in the sun. The radius of the house and grounds was as far as an Echo could stray from where she had formed. And Bethie was happy here! Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes shining with lights. Often she would press her hands together under her chin, tight against her thin frame, as if the excitement was too much for her to contain.

I know I had once been Bethie, but it seemed so unreal a thought as to be impossible. I envied her a little; I would have liked to stay Bethie forever.

“I’m sorry honey, but I have to do this alone,” I said as she wormed her way under my arm to hug me again, looking more tremulous than I’d ever seen her. She would forget me as soon as I was out of sight, I felt pretty sure, but I gripped her hard in this moment for my own sake.

I heard the padding of soft feet on the path and I looked up to see eleven-year-old Libby coming from the house. “Someone’s here,” she said, a spark of curiosity mixed in with her usual demeanor of crushing disappointment.

It had been years since someone had last come to the house. My father did not tend to encourage visitors and most of the townsfolk were in too much awe or fear of him to venture close. I ran quickly back up the path, my two Echoes behind me.

She was just getting out of her carriage as I reached the front of the house. Her dark hair was up in some sort of untidy mass at the back of her head, and she was wearing trousers instead of the long skirt that was customary. Her face angled towards me in the high, bright light of the sun, and my breath caught in my throat.

It was my mother.

It wasn’t, of course, although when I started breathing again the air felt hot and forced in my lungs. I clutched at the hands of the Echoes on either side of me—Libby’s hand felt feather-light and insubstantial in my own, but Bethie’s grip was as real and solid as ever. For an instant the visitor had looked like my mother, but she was not. And then I knew who she was.

“Aunt Marla,” I said, letting go of the hands in mine, and hurtling forward two steps to throw my arms around her neck. I was almost as tall as she was. “Aunt Marla, can I go with you? Oh, can I go with you? I can’t stay here, I’m leaving today. I was going to try and look for you anyway, once I got to town.” My words stumbled clumsily over themselves.

Aunt Marla looked at me oddly. I probably shouldn’t have made my request like that, so suddenly and fiercely, when I hadn’t even seen her in more than a decade. “Hello Elizabeth,” she said. She didn’t smile and her eyes were very dark, like my mother’s. “Yes, you may come with me when I go.”

A flash of hope mixed with the slow boil of my anger that was underneath everything today, the combination making me tremble.

I suddenly realized that she could see three of us and wondered if she was confused. “These are my … um, I mean …” I began, flustered.

“I know about the Echoes,” said Aunt Marla, although she only looked at me. “You have been doing that since you were very young.”

She must have found me as changed as I found her. The last time she’d seen me, I would have been a much smaller version of Bethie. Aunt Marla looked faintly sad and old and tired, and none of these were things I had associated with my mother’s younger sister, although of course she was older now than my mother had ever lived to be.

“Would you like me to take you to Father?” I tried to keep my voice steady as I tried, belatedly, to remember my manners.

“No,” she said after a pause. “I can go and find him.” I felt relieved. The curiosity I had over how he would react to the return of my disfavored aunt was not enough to entice me within my Father’s radius. It felt as if we had burned up all the space and air between us with our words last night.

I wondered how long Aunt Marla would stay. It was likely Father would turn her out immediately.

Which meant there was one more goodbye I could no longer avoid.

The sitting room was dim and dusty, and when I opened up the curtains all it did was illuminate the grime. There was a faint scent of old dried flowers. I couldn’t see her at first but I crouched down and found her under the table, her small face pressed up against one of the thick carved wooden legs.

“Hello Elly,” I said softly, but she didn’t look at me, only snuffled like a baby animal and wiped her hand against her nose and then onto the blue of her smock. Even in the shadows I could see that she was sharply defined and solid. Her hair was undone and her dark eyes were large and hunted. When all of the other Echoes had faded, Elly would remain, I knew. She would be here for as long as I lived.

“I’ve come to say goodbye,” I said, although I didn’t think it was any use trying to talk to her. She looked at me then though, and I could see that tears were trembling on her lashes. It was the word “goodbye,” I thought. She knows that word. She knows that word better than anyone.

I put out my hand very slowly and touched her hair. “It’s okay,” I said. The words felt rough in my throat because they were a lie. I felt a hot prickle of guilt down my spine—I never came to see Elly, I avoided the sitting room. But how could I tell her the truth? For her it was not okay, it would never be okay. She was caught forever in the day my mother died.

I sat with Elly for a long time, as if somehow my presence would mean something to her although I knew it couldn’t. When I left, I met Aunt Marla at the door.

“May I go and see her?” she asked curtly, and I nodded. I didn’t know what she wanted with Elly, but maybe she wanted to say goodbye too. I presumed from her abrupt manner that things had not gone well with my father, which did not surprise me at all.

I had thrown clothes and some belongings into a bag the night before, and I figured I would put it in Aunt Marla’s carriage, so that nothing would delay our departure. I felt like my blood was surging with the need to flee, to begin the new life that I was obviously fated to have; why else would my Aunt have showed up on the very day I was going to leave?

But something tugged at me as I went down the hall and through to the wide steps of the staircase. Like when a painting that has been there many years is moved, and you have taken it so much for granted that you don’t even see it anymore and couldn’t say what was drawn there, but the empty space feels wrong and creases your brow. Or when a sound you are so used to that you don’t even register anymore suddenly ceases.

A sound. I realized that it was very, very quiet. The house felt oddly undisturbed, and the little hairs on my arms stood up. The sense of stillness increased as I went through the house, my own footsteps coming louder and faster by contrast.

Three stairs up, I stopped as I put my finger on the feeling. I felt alone. Even though I was a girl with a dead mother and a distant father, I had never felt alone like this before. I forgot all thoughts of my bag and went by instinct out to the porch.

The patio-swing was still and unmoving, and there was no one there. The Echoes often moved around even though they had their favorite haunts, so that was not that unusual. But there was no one anywhere. Years and years of Echoes, fading to various degrees, but always there layering my days with faint whispers and babbles in the background, the flicker of shadows that were barely there, the smell of ozone.

There was nothing.

“Aunt Marla,” I called, desperate with confusion. I turned on my heel and dashed back the way I had come, my running feet leaving little footprints in the dust.

I swung open the sitting room door, but my Aunt was not there. I walked over to the table, my steps slow and deliberate now, and crouched to look under it. Elly was gone.

None of this made any sense. Elly never left the sitting room. I rubbed at my arms, which had come out in goosebumps. Many different emotions warred in my chest, but anger won out. What. Was. Going. On?

“Aunt Marla!” I yelled, running from room to room, all empty, all quiet. “Where are you?”

There. The front door was open. I ran outside and down the steps past the hoard of sunflowers. I shaded my eyes against the slanted rays of the sun as I started down the path. Against the glare I could make out one figure. No, two.

“Aunt Marla,” I shrieked again, fear mixing in with the heat of my anger and making my voice croaky.

They were still too far away. I could see Aunt Marla holding something in her hand, pointing it forward. I could see the child in front of her, the tilt of her little trusting face.

Bethie. Bethie. Bethie. Not Bethie.

The ivory-white stick Aunt Marla held seemed to shine brightly for a moment, and Bethie dispersed like she was made of rain.

“Noooooo,” I yelled. I felt myself boiling and bubbling as if I were full of steam. Surely I had other magic? I put my hands together, stretched them straight out in front of me, and willed myself to blast Aunt Marla with a pure bolt of my rage.

Aunt Marla turned and looked at me. Her face was impassive and she did not keel over or erupt into flame or show any signs of discomfort at all.

I walked towards her, my eyes on what she held in her hand. Aunt Marla with a wand? I had always been told that my mother’s side of the family had no talent for magic. She held the wand lightly, but it was pointed straight at me.

“Aunt Marla, what are you doing?” the steam I’d felt had evaporated, leaving an empty space inside me. Bethie.

Aunt Marla didn’t react to my question, and I realized that was not her name. She had never been Aunt Marla at all.

“Who are you?” I said to not-Aunt-Marla. I stopped in the dirt of the path and she took the last few steps towards me.

The corner of her mouth moved a little but it was nothing that could be called a smile. “I’m Elizabeth,” she said.

Her eyes looked tired yet so familiar. “I don’t believe you,” I said.

“Did you notice that you didn’t make an Echo? After the big fight with your father, after you decided to leave? Why do you think that was?” Despite the little wry note in her voice, her face was serious.

It was true. Even caught in the fierce and consuming emotions of last night, no Echo had formed. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t noticed that before.

Non-Aunt-Marla-Elizabeth must have seen my confusion. “You’re me, or at least, you’re a copy of me when I was young.”

I looked down at my arms, which had crossed themselves defensively over my chest. They were firm, solid, real. “I don’t believe you,” I said again. But I believed her.

I looked at the wand, dipped downwards now but still pointed roughly in my direction. “Why do you want to make me go?” I blurted. I could feel the blood coursing in my veins, my heart thumping in my chest, bringing heat to my face, pounding so hard I expected to see an Echo made of this moment, but there was none. Because I was an Echo myself.

“He was right you know, your father,” and now grown-up-Elizabeth’s eyes flickered away from me and off into the distance. “The world is swirled in complexity and darkness. It is the darkness he wanted to save you … save me from. It is not as pretty as you thought it was going to be. Neither is it as exciting. But I did find Aunt Marla, and she was right: it is my world and I deserved to take my place in it.”

I thought of Bethie, of Elly, Libby, Eliza, Betty, Liz, and many others so faded that their names were forgotten. All of the companions I had grown up with, or thought I did. Now there was only me. “Why?” I asked her again.

“Because you are all part of me,” she said. “You all hold these things for me, these feelings, and I need them back, I have to own them myself.” She paused and then added quietly, “It is the only way I can be whole.”

“Why did you take all of the others first? I was right there, you could have zapped me with that thing right away.”

I wasn’t sure if her eyes softened. “Because I’ve never spoken to you before. I never knew you. I fought with my father that day, and I left. I never came back. I learned, eventually, to take back the Echoes just after I made them, so that I could keep what it was I felt, even if it was hard that way. My father died, a year ago, and I haven’t seen him since I was fifteen. Since I was you.”

My father? I shot an involuntary glance back up at the house, and realized I was shaking like a leaf in the wind.

“Yes,” said Elizabeth, although I had not asked the question. “You’ve been here a long time.”

Elizabeth raised the wand, which started shining. She was so grim and cold and uncaring, how could that be me? How could I turn into her?

I felt things loosen, I started to shimmer.

And then I saw it.

Coalescing just behind her, glimmering and shifting, forming, becoming. Her Echo, written in grief and sadness on the air.

And the faint scent of ozone.